Modelling Qualitative Data from Repeated Surveys

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method and Materials

2.1. The Dynamic CUB Model

2.2. Estimation and Fitting Measure

- firstly, data are organized as a matrix, R, where rows are given by , ;

- a bootstrap sample is created by resampling T rows from R with replacement. This preserves the dependency of each ordinal distribution with the explicative variables;

- the bootstrap estimates of the parameters are evaluated by fitting the model (1) to the bootstrap sample;

- the bootstrap replicates of the time-varying parameter estimates are obtained using (3).

2.3. Data Description

Q5. How do you think that consumer prices have developed over the last 12 months? They have: risen a lot; risen moderately; risen slightly; stayed about the same; fallen.

Q6. By comparison with the past 12 months, how do you expect consumer prices will develop in the next 12 months? They will: increase more rapidly; increase at the same rate; increase at a slower rate; stay about the same; fall.

3. Results

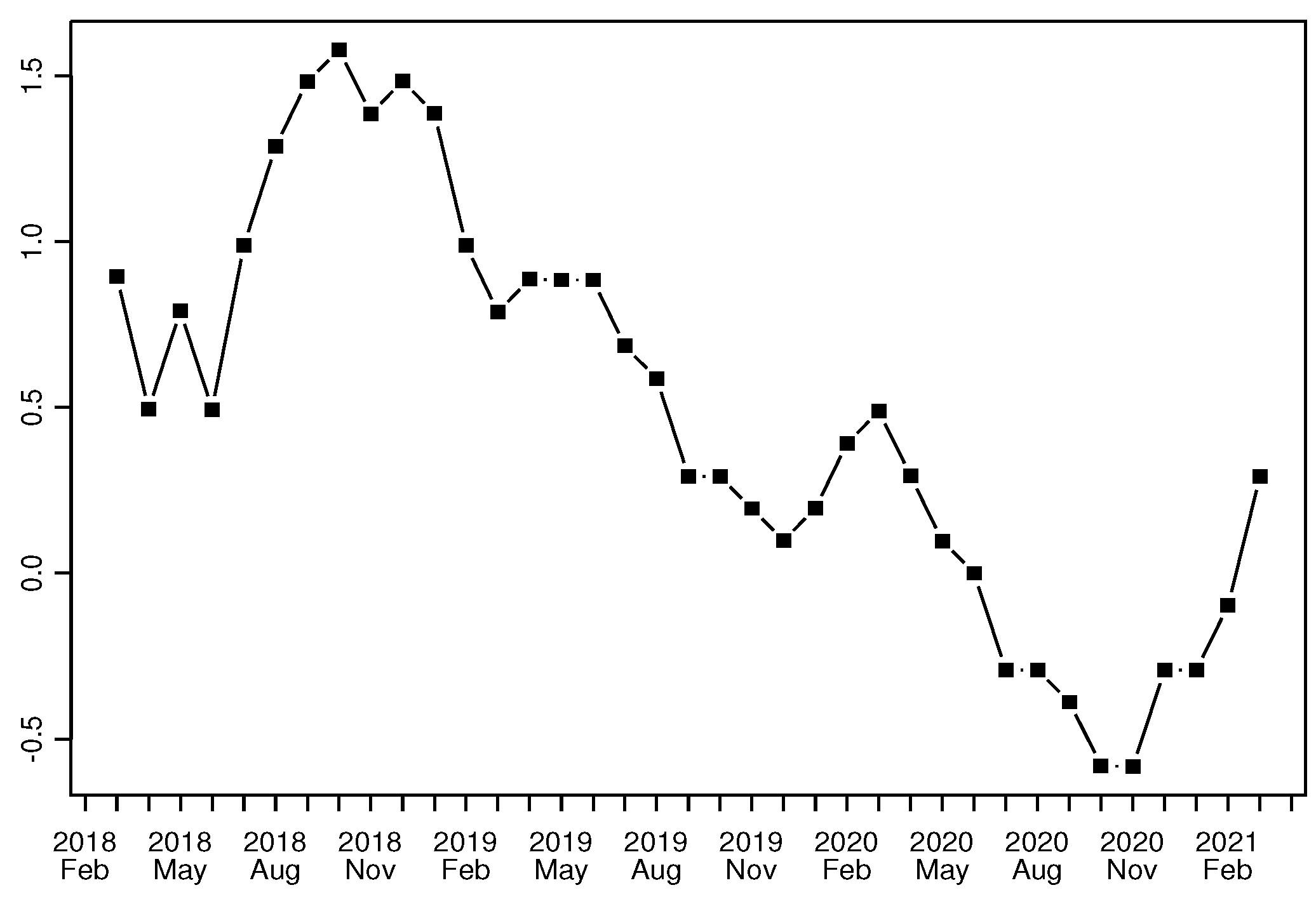

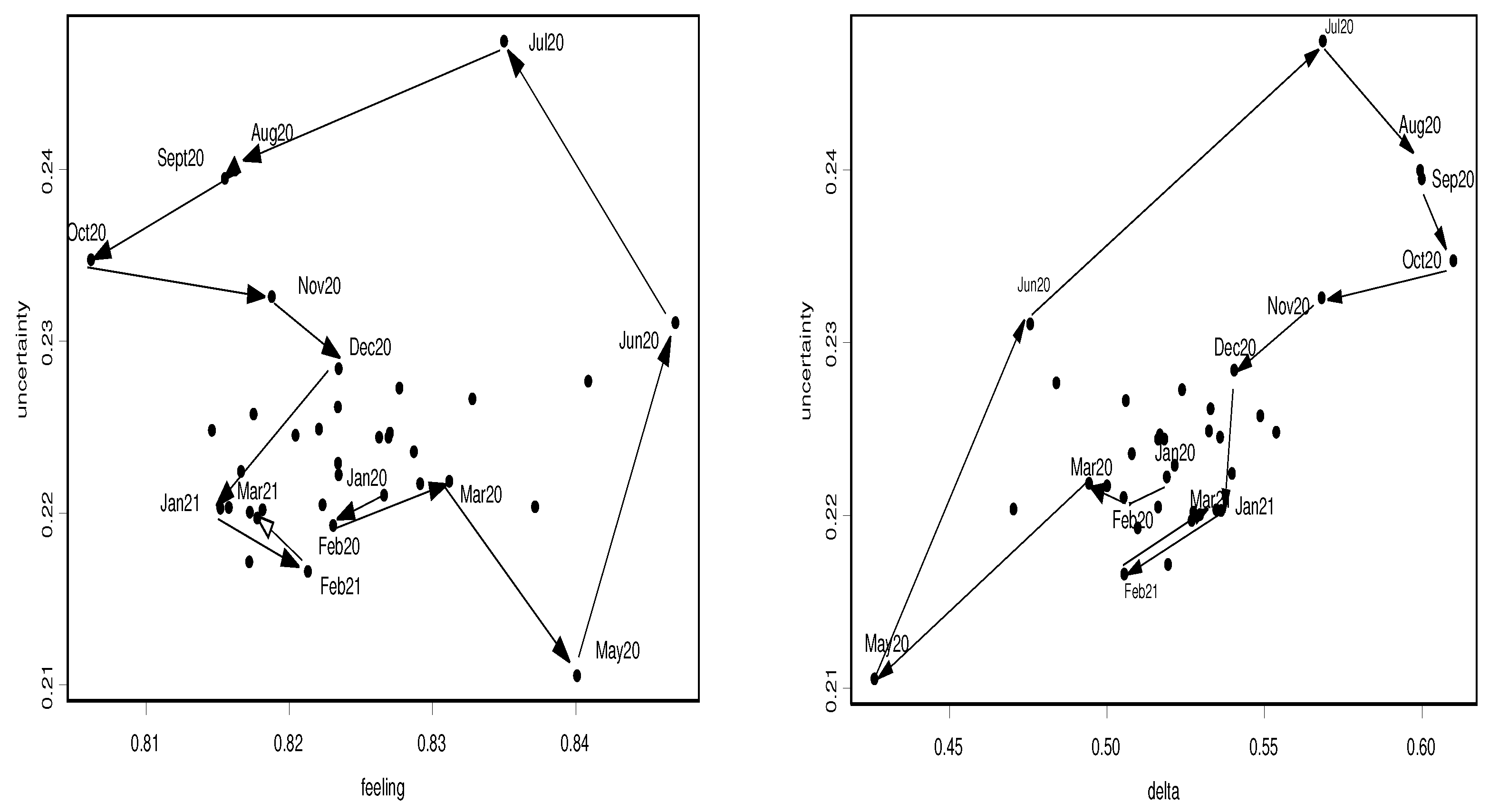

3.1. The Effect of the COVID Pandemic on Consumers’ Opinions about Inflation

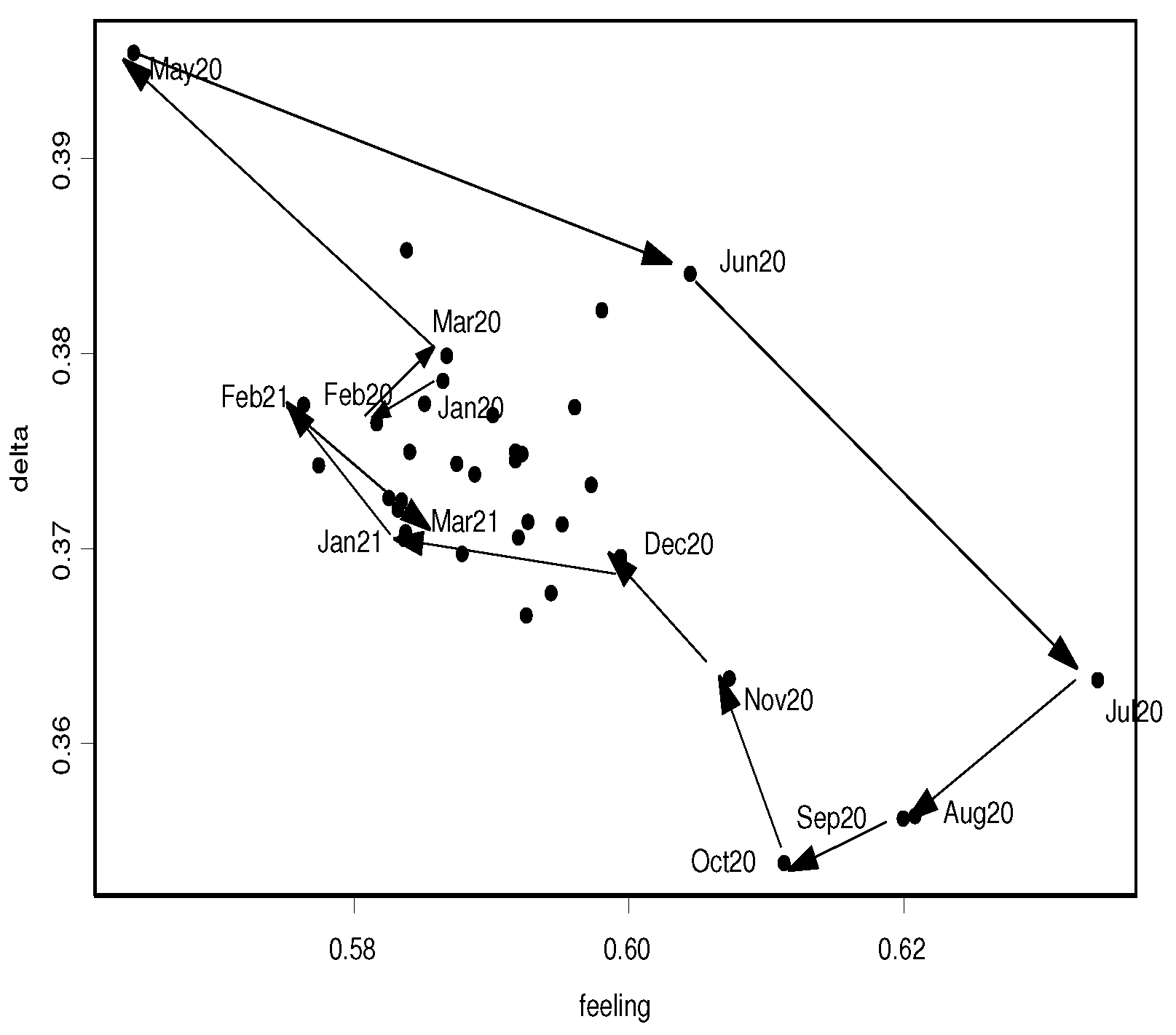

3.2. The Evolution of Inflation Expectations by Income Group

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mitchell, J.; Smith, R.J.; Weale, M.R. Forecasting manufacturing output growth using firm-level survey data. Manch. Sch. 2005, 73, 479–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theil, H. On the time shape of economic microvariables and the Munich business test. Int. Stat. Rev. 1952, 20, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.; Parkin, M. Inflation expectations. Economica 1975, 42, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. Expectation formation and macroeconomic modelling. In Contemporary Macroeconomic Modelling; Malgrange, P., Muet, P.A., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1984; pp. 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Nardo, M. The quantification of qualitative survey data: A critical assessment. J. Econ. Surv. 2003, 17, 645–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proietti, T.; Frale, C. New proposals for the quantification of qualitative survey data. J. Forecast. 2011, 30, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, D. On the moments of a mixture of uniform and shifted binomial random variables. Quad. Stat. 2003, 5, 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo, D.; Simone, R. The class of CUB models: Statistical foundations, inferential issues and empirical evidence, (with discussion and rejoinder). Stat. Meth. Appl. 2019, 28, 389–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, D. Observed information matrix for MUB models. Quad. Stat. 2006, 8, 33–78. [Google Scholar]

- Corduas, M.; Iannario, M.; Piccolo, D. A class of statistical models for evaluating services and performances. In Statistical Methods for the Evaluation of Educational Services and Quality of Products; Monari, P., Bini, M., Piccolo, D., Salmaso, L., Eds.; Physica: Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo, D.; Simone, R.; Iannario, M. Cumulative and CUB models for rating data: A comparative analysis. Int. Stat. Rev. 2019, 87, 207–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proietti, T. Discussion of “The class of CUB models: Statistical foundations, inferential issues and empirical evidence”. Stat. Meth. Appl. 2019, 28, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, R.; Piccolo, D.; Corduas, M. Dynamic modelling of price expectations. In CLADAG 2019-Book of Short Papers; Porzio, G.C., Greselin, F., Balzano, S., Eds.; Edizioni Università di Cassino: Cassino, Italy, 2019; Available online: http://cladag2019.unicas.it/book-of-abstracts/ (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Clar, M.; Duque, J.C.; Moreno, R. Forecasting business and consumer surveys indicators: A time-series models competition. Appl. Econ. 2007, 39, 2565–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arioli, R.; Bates, C.; Dieden, H.; Duca, I.; Friz, R.; Gayer, C.; Kenny, G.; Meyler, A.; Pavlova, I. EU Consumers’ Quantitative Inflation Perceptions and Expectations: An Evaluation; EU Economy Discussion Paper, n. 38; European Central Bank: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Capecchi, S.; Iannario, M. Gini heterogeneity index for detecting uncertainty in ordinal data surveys. METRON 2016, 74, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkson, J. Minimum chi-square, not maximum likelihood! Ann. Stat. 1980, 8, 457–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.R.; Kanji, G.K. On the use of minimum chi-square estimation. J. R. Stat. Soc. D 1983, 32, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressie, N.; Read, T.R. Multinomial goodness-of-fit tests. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 1984, 46, 440–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, L. Statistical Inference Based on Divergence Measures; Chapmann & Hall/CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, C.R. Asymptotic efficiency and limiting information. In Proceedings of the Fourth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1961; Volume 1, pp. 531–546. [Google Scholar]

- Corduas, M. A dynamic model for ordinal time series: An application to consumers’ perceptions of inflation. In Statistical Learning and Modeling in Data Analysis; Balzano, S., Porzio, G.C., Salvatore, R., Vistocco, D., Vichi, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R.J. An Introduction to the Bootstrap; Chapman and Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri, S.N. Resampling Methods for Dependent Data; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ranyard, R.; Del Missier, F.; Bonini, N.; Duxbury, D.; Summers, B. Perceptions and expectations of price changes and inflation: A review and conceptual framework. J. Econ. Psychol. 2008, 29, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corduas, M. Gender differences in the perception of inflation. J. Econ. Psychol. 2022, 90, 102522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, P.; Weiserbs, D. Consumer Price Perceptions and Expectations. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 1992, 44, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chang, H.; Lobonţ, O.; Su, C. Modeling heterogeneous inflation expectations: Empirical evidence from demographic data? Econ. Mod. 2016, 57, 53–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döhring, B.; Mordonu, A. What Drives Inflation Perceptions? A Dynamic Panel Data Analysis; Economic Papers n. 284; European Commission: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2007.

- Greitemeyer, T.; Schulz-Hardt, S.; Traut-Mattausch, E.; Frey, D. The influence of price trend expectations on price trend perceptions: Why the Euro seems to make life more expensive? J. Econ. Psychol. 2005, 26, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traut-Mattausch, E.; Schulz-Hardt, S.; Greitemeyer, T.; Frey, D. Expectancy confirmation in spite of disconfirming evidence: The case of price increases due to the introduction of the Euro. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 739–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancotti, C.; Rosolia, A.; Veronese, G.; Kirchner, R.; Mouriaux, F. COVID-19 and Official Statistics: A Wakeup Call? Bank of Italy Occasional Paper, n. 605; Banca d’Italia: Rome, Italy, 2021.

- Cavallo, A. Inflation with Covid Consumption Baskets; NBER Working Paper n. 27352. 2020. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w27352 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Coleman, W.; Nautz, D. Inflation Expectations, Inflation Target Credibility and the COVID-19 Pandemic: New Evidence from Germany. J. Money Credit Bank 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; Iskrev, N.; Pires Ribeiro, P. Euro Area Inflation Expectations during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Banco de Portugal Economic Studies. 2021. Available online: https://www.bportugal.pt/sites/default/files/anexos/pdf-boletim/reev7n3_e_0.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Armantier, O.; Kosar, G.; Pomerantz, R.; Skandalis, D.; Smit, K.; Topa, G.; van der Klaauw, W. How economic crises affect inflation belief: Evidence from COVID-19 pandemic. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2021, 189, 443–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, C. Coronavirus Fears and Macroeconomic Expectations. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2020, 102, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruine de Bruin, W.; Vanderklaauw, W.; Downs, J.S.; Fischhoff, B.; Topa, G.; Armantier, O. Expectations of inflation: The role of demographic variables, expectation formation, and financial literacy. J. Consum. Aff. 2013, 44, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, X.; Hui, H.W.; Liu, F.F.; Bai, Y.L. Stability and optimal control strategies for a novel epidemic model of COVID-19. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 106, 1491–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Zhu, Q.; Lü, X. Parameter estimation of the incubation period of COVID-19 based on the doubly interval-censored data model. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 106, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georganas, S.; Healy, P.J.; Li, N. Frequency bias in consumers’ perceptions of inflation: An experimental study. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2014, 67, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, O.W. Frequency of price increases and perceived inflation: An experimental investigation. J. Econ. Psychol. 2021, 32, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cogn. Psychol. 1973, 5, 207–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceptions | 1.157 | −0.517 | −0.847 | 0.214 | |||

| (0.019) | (0.006) | (0.010) | (0.008) | ||||

| Expectations | 2.333 | −0.370 | −0.017 | −0.518 | −0.090 | −0.897 | |

| (0.228) | (0.077) | (0.754) | (0.255) | (0.008) | (0.051) |

| Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st quartile | −4.267 | 1.479 | 0.481 | −0.487 | −0.367 | 0.435 | |

| (0.674) | (0.194) | (0.423) | (0.122) | (0.054) | (0.095) | ||

| 2nd quartile | −2.622 | 1.038 | 1.692 | −0.859 | −0.352 | 0.469 | |

| (0.392) | (0.251) | (0.829) | (0.251) | (0.055) | (0.087) | ||

| 3rd quartile | −1.831 | 0.852 | 1.987 | −0.953 | −0.310 | 0.334 | |

| (0.817) | (0.255) | (0.385) | (0.124) | (0.059) | (0.101) | ||

| 4th quartile | −2.018 | 0.906 | 2.274 | −1.043 | −0.413 | 0.379 | |

| (0.707) | (0.228) | (0.430) | (0.136) | (0.043) | (0.069) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Corduas, M.; Piccolo, D. Modelling Qualitative Data from Repeated Surveys. Computation 2023, 11, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation11030064

Corduas M, Piccolo D. Modelling Qualitative Data from Repeated Surveys. Computation. 2023; 11(3):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation11030064

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorduas, Marcella, and Domenico Piccolo. 2023. "Modelling Qualitative Data from Repeated Surveys" Computation 11, no. 3: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation11030064

APA StyleCorduas, M., & Piccolo, D. (2023). Modelling Qualitative Data from Repeated Surveys. Computation, 11(3), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation11030064