HSE-GNN-CP: Spatiotemporal Teleconnection Modeling and Conformalized Uncertainty Quantification for Global Crop Yield Forecasting

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Most machine learning approaches model locations independently or use simplistic spatial features like latitude and longitude. This fails to capture the complex inter-regional coupling induced by teleconnections. Graph neural networks (GNNs) offer a framework for encoding these structured relationships, but their application to agriculture remains nascent [7].

- Ensemble and Bayesian methods provide uncertainty estimates but often lack finite-sample validity guarantees. Conformal prediction, a distribution-free framework that guarantees marginal coverage under minimal assumptions [8], has seen limited adoption in agricultural AI despite its utility for high-stakes decision-making.

- Yield forecasts are most actionable when accompanied by complementary drought severity classification and calibrated uncertainty bounds. Integrated multi-task frameworks that jointly address prediction, classification, and risk are currently scarce.

- Primary Methodological Contribution: The primary novelty is the development and validation of a conformalized quantile regression (CQR) wrapper for bootstrap ensembles in agricultural forecasting. While bootstrap methods are common for generating prediction distributions [11], they frequently suffer from significant under-coverage in yield data. The CQR approach provides a rigorous finite sample coverage guarantee in this domain [8], correcting uncalibrated bootstrap intervals from 40.03% to a valid 80.72% coverage. This represents a fundamental shift from heuristic uncertainty estimation to mathematically guaranteed reliability for agricultural risk management.

- Secondary Innovations and Methodological Integration: In addition to the primary uncertainty framework, three secondary contributions are provided through the novel integration of existing methodologies:

- ○

- Global climate structures are explicitly modeled by constructing a spatial graph where edges are defined by historical rainfall correlations. A 2-layer graph convolutional network (GCN) is integrated to learn 64-dimensional embeddings that propagate information along these teleconnection pathways [7,11,12], This provides a structured representation of climate dependencies that improves predictive accuracy over standard spatial features.

- ○

- ○

- The synergistic benefit is demonstrated a holistic framework that jointly performs yield prediction and drought severity classification via MSI thresholds. Testing this integrated pipeline on a global multi-crop dataset produces a comprehensive decision support tool that outperforms fragmented single task models.

2. Related Work

2.1. Crop Yield Prediction

2.2. Climate Teleconnections in Agriculture

2.3. Uncertainty Quantification

2.4. Explainability in Agricultural AI

3. Problem Formulation and Dataset

3.1. Problem Formulation

- Point prediction: Learn a function that produces a yield estimate

- Uncertainty quantification: Construct prediction intervals that satisfy for a chosen miscoverage rate , with guarantees under exchangeability.

- Drought classification: Assign each sample to one of the categories using thresholds derived from the moisture stress index.

3.2. Global Crop Yield Dataset

3.2.1. Data Sources

- Annual country-level yield data (1990–2023) obtained from the FAO Statistics Division (FAOSTAT) [58].

- Averaged temperature (°C) and aggregate rainfall (mm/year) derived from global reanalysis products [59].

- Fertilizer and pesticide consumption data (tonnes per country per year) sourced from the FAO [58].

- The ENSO index (specifically the Oceanic Niño Index, ONI) from the NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory, and the NAO index from the Climate Research Unit (CRU) [60].

- The final processed dataset, including all engineered features and teleconnection indices, has been archived for reproducibility and is available at: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/y7hkz2zfcc/1 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

3.2.2. Dataset Scope

- Fifteen countries across six continents: Australia, Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Iran, Kenya, Mexico, Peru, Russia, Thailand, Turkey, USA, Vietnam. These nations represent diverse agro-climatic zones (tropical, temperate, arid, monsoon-influenced) and account for significant global production shares.

- Six major staples and cash crops: wheat, rice, maize, soybeans, barley, potatoes. Together, these crops dominate global caloric supply and trade volumes.

- A time span of 34 years (1990–2023), encompassing multiple ENSO cycles, technological adoption phases (e.g., improved seed varieties, precision agriculture), and climate variability trends.

- N = 3060 observations (15 countries × 6 crops × 34 years = 3060 country–crop–year tuples).

3.3. Feature Space and Descriptive Statistics

- Year t

- Area or country a, categorical

- Item or crop c, categorical

- Latitude in degrees north

- Longitude in degrees east

- Average temperature in degrees Celsius

- Average rainfall in millimeters per year

- Pesticides in tonnes

- ENSO index, dimensionless

- NAO index, dimensionless

- Yield in hectogram per hectare, target variable

- Yield: Mean 37,720 hg per ha. Standard deviation 24,527 hg per ha. Minimum 552 hg per ha. Maximum 151,349 hg per ha. The range reflects differences across crops.

- Temperature: Mean 17.2 °C. Standard deviation 6.2 °C.

- Rainfall: Mean 1147 mm per year. Standard deviation 512 mm per year.

- ENSO index: Mean near 0. Standard deviation 0.58.

- NAO index: Mean near 0. Standard deviation 0.69.

4. Methodology

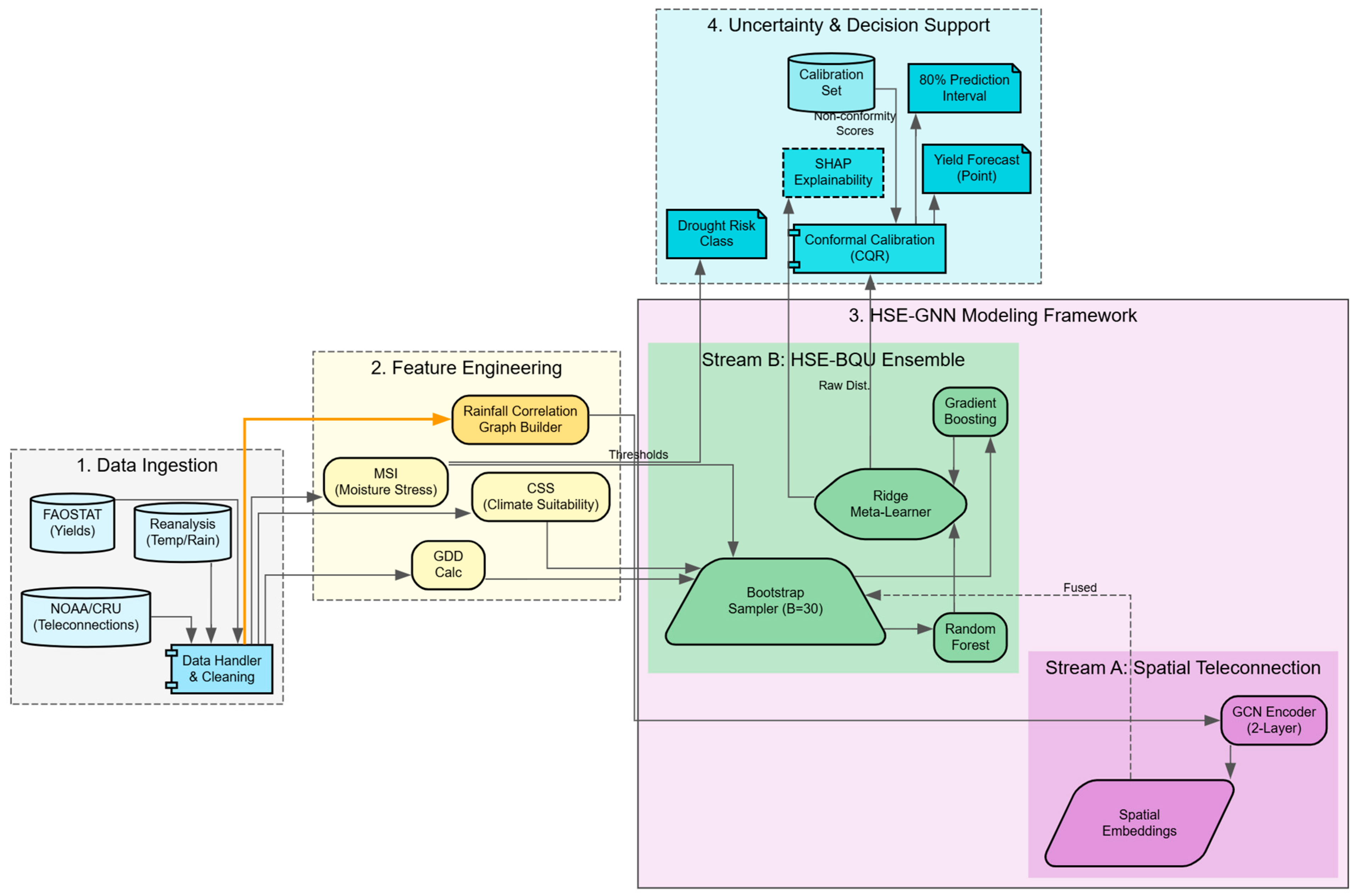

4.1. System Architecture Overview

4.2. Agronomic Feature Construction

4.2.1. Growing Degree Days (GDD)

4.2.2. Moisture Stress Index (MSI)

4.2.3. Climate Suitability Score (CSS)

4.2.4. Temperature Component

4.2.5. Rainfall Component

4.2.6. Technology Index

4.2.7. Feature Vector Construction

4.3. HSE-BQU: Heterogeneous Stacked Ensemble

- Level 1 (Base Learners): Two complementary models capture different aspects of the data:

- ○

- Random forest (RF): Bagging-based ensemble of decision trees, robust to outliers and capable of modeling complex interactions. Configuration: 50 trees, max_depth = 12, feature subsampling at each split.

- ○

- Gradient boosting (GB): Sequential additive model minimizing residuals, effective for capturing fine-grained patterns. Configuration: 50 estimators, max_depth = 5–6, learning rate tuned via validation.

- ○

- While both random forest and gradient boosting are tree-based methods, they capture complementary aspects of the data-generating process, which justifies their combined use in the ensemble.

- ○

- The random forest bagging approach builds independent trees via bootstrap aggregation. This provides robustness to outliers, stable variance estimates critical for uncertainty quantification, and a parallel ensemble structure that efficiently handles high-dimensional feature spaces. Random forest excels at capturing diverse patterns through randomized feature selection at each split.

- ○

- In contrast, the gradient boosting approach sequentially fits trees to residuals. This method excels at capturing fine-grained patterns, complex feature interactions, and subtle relationships missed by parallel ensembles. The additive structure of gradient boosting provides a modeling capacity that is complementary to the averaging approach used in random forest.

- ○

- Empirical evaluation confirms these distinct error profiles. Standalone random forest achieves an , while standalone gradient boosting achieves an . The heterogeneous stack leverages this diversity through meta-regression, automatically weighting their contributions. Ablation studies revealed that using only random forest or only gradient boosting yielded inferior performance, with values approximately 0.94, compared to the heterogeneous stack, which achieved . This validates the approximately 1.5 percentage point gain from model diversity.

- ○

- Regarding alternative Gradient Boosting implementations, LightGBM and CatBoost may offer marginal computational or accuracy gains, but the focus is on demonstrating methodological principles such as conformalized ensembles and spatial modeling rather than maximizing benchmark scores. The chosen implementation balances performance, interpretability, and reproducibility. Future work could explore Gradient Boosting variants as drop-in replacements.

- Level 2 (Meta-Learners): Ridge regression combines base learner predictions as shown in Equation (6) [63].

- ○

- Bootstrap mechanism: To generate prediction distributions, independent stacks are trained, each on a bootstrap resample (sampling with replacement) of the training set as shown in Equation (7).

- ○

- Point prediction: Median of bootstrap predictions (robust to outliers), as shown in Equation (8).

- ○

- Heuristic uncertainty interval: Percentile method (before conformal calibration) as shown in Equation (9).

| Algorithm 1: HSE-BQU Training |

| Input: Training set

, number of bootstraps

Output: Ensemble FOR TO :

|

4.4. Conformal Prediction for Valid Coverage Guarantees

4.4.1. Exchangeability and Coverage Guarantee

4.4.2. Conformalized Quantile Regression (CQR)

- Step 1: Data Split

- ○

- Training set (60%): Used to train HSE-BQU

- ○

- Calibration set (20%): Used to compute non-conformity scores

- ○

- Test set (20%): Final evaluation

- Step 2: Compute Heuristic Intervals on Calibration Set

- ○

- For each calibration sample , obtain bootstrap quantiles .

- Step 3: Non-Conformity Scores

- ○

- Measure how much the true label lies outside the heuristic interval .

- ▪

- If , then (conforming).

- ▪

- If , then (non-conforming below).

- ▪

- If , then (non-conforming above).

- Step 4: Calibration Quantile

- ○

- Compute the -quantile of non-conformity scores with finite-sample correction for and , the quantile is computed.

- Step 5: Conformalized Test Intervals

- ○

- For test sample , apply symmetric adjustment .

- Theorem (Marginal Coverage Guarantee): Under exchangeability, .

| Algorithm 2: Conformal Calibration |

| Input: Calibration set

trained ensemble

target coverage

Output: Calibration factor

|

4.5. Spatial-Temporal GNN for Teleconnection Modeling

| Algorithm 3: Teleconnection GNN Construction and Training |

| Input: Historical Dataset

Target Yields

, Correlation Threshold

Output: Spatial Embeddings , Trained Model Parameters // Phase 1: Graph Construction For each year and country , compute average rainfall:

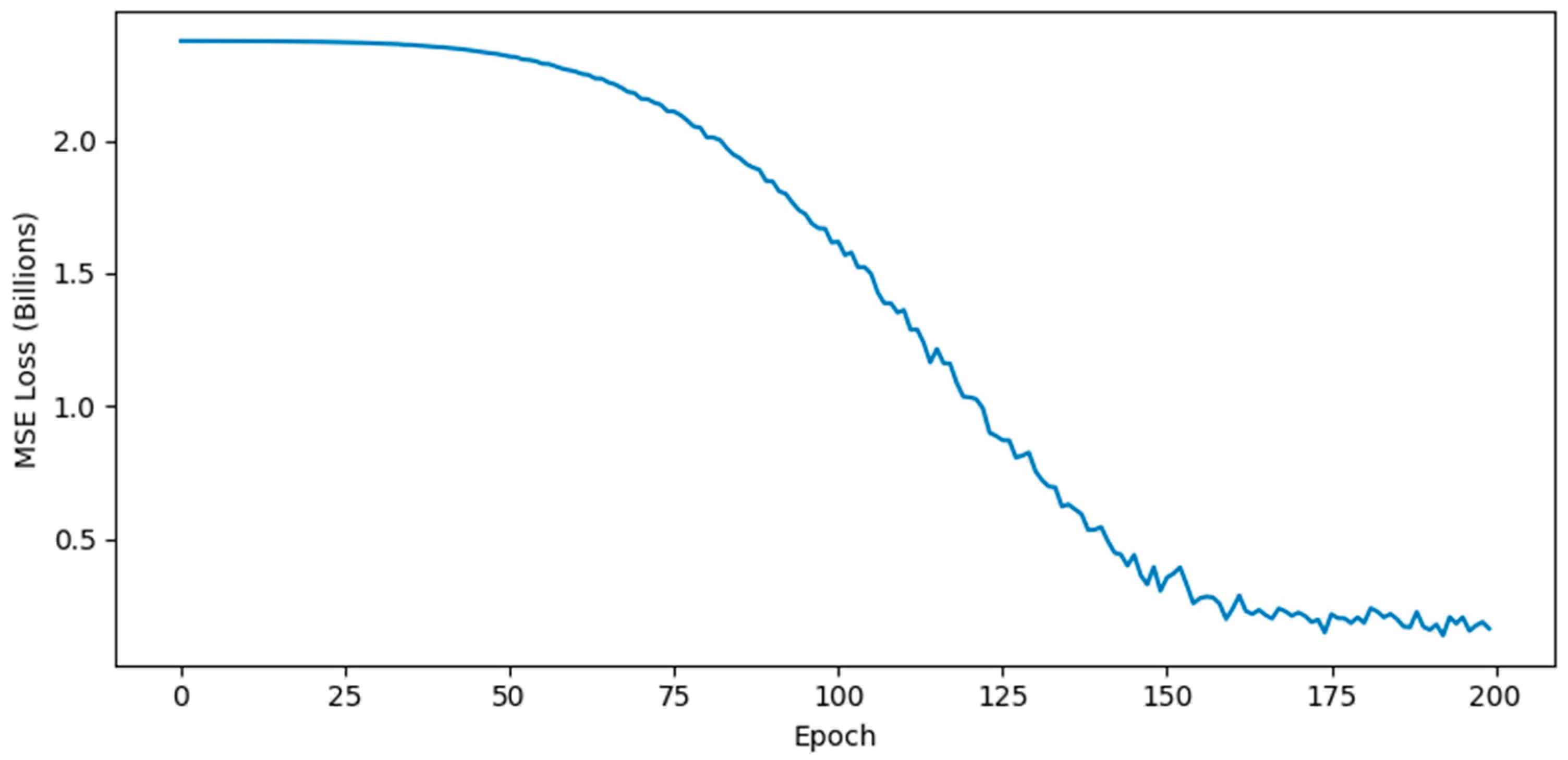

7. Initialize weights 8. FOR epoch TO 200: 9. Layer 1 (Message Passing): 10. Apply Dropout 11. Layer 2 (Diffusion): 12. Prediction: 13. Update: Minimize MSE Loss via Adam. 14. RETURN |

4.5.1. Graph Construction from Rainfall Correlations

4.5.2. Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) Architecture

- Layer 1: Aggregates information from direct neighbors. Dropout () is applied to prevent overfitting on the small graph.

- Layer 2: Aggregates information from neighbors of neighbors. This 2-hop propagation is crucial as it allows the model to capture indirect teleconnection pathways.

4.5.3. Enhanced GNN Architecture and Training

- All regions maintain meaningful connectivity (no isolated nodes)

- Weak spurious correlations are excluded (reduces noise)

- Balanced graph structure (all nodes have equal out-degree)

- Long-term climatological patterns (e.g., the ENSO’s consistent influence on the Pacific rim, monsoon belt co-variability) exhibit greater stability than year-to-year fluctuations.

- Static graphs reduce computational complexity and enhance interpretability, as the learned structure can be validated against known teleconnection science.

- Preliminary analysis showed that year-to-year correlation variation (temporal standard deviation ~0.15) was substantially smaller than inter-regional differences (spatial standard deviation ~0.45), suggesting that the dominant signal is stable.

- Finite sample considerations: with only 34 years of data, estimating reliable time-varying correlation matrices would introduce substantial estimation uncertainty.

- Temporal graph neural networks (T-GCN, STGCN) that learn time-varying adjacency matrices from sequential data.

- Windowed correlation estimation that allows graph structure to evolve across multi-year periods.

- Context-dependent graphs conditioned on climate state variables (PDO, AMO).

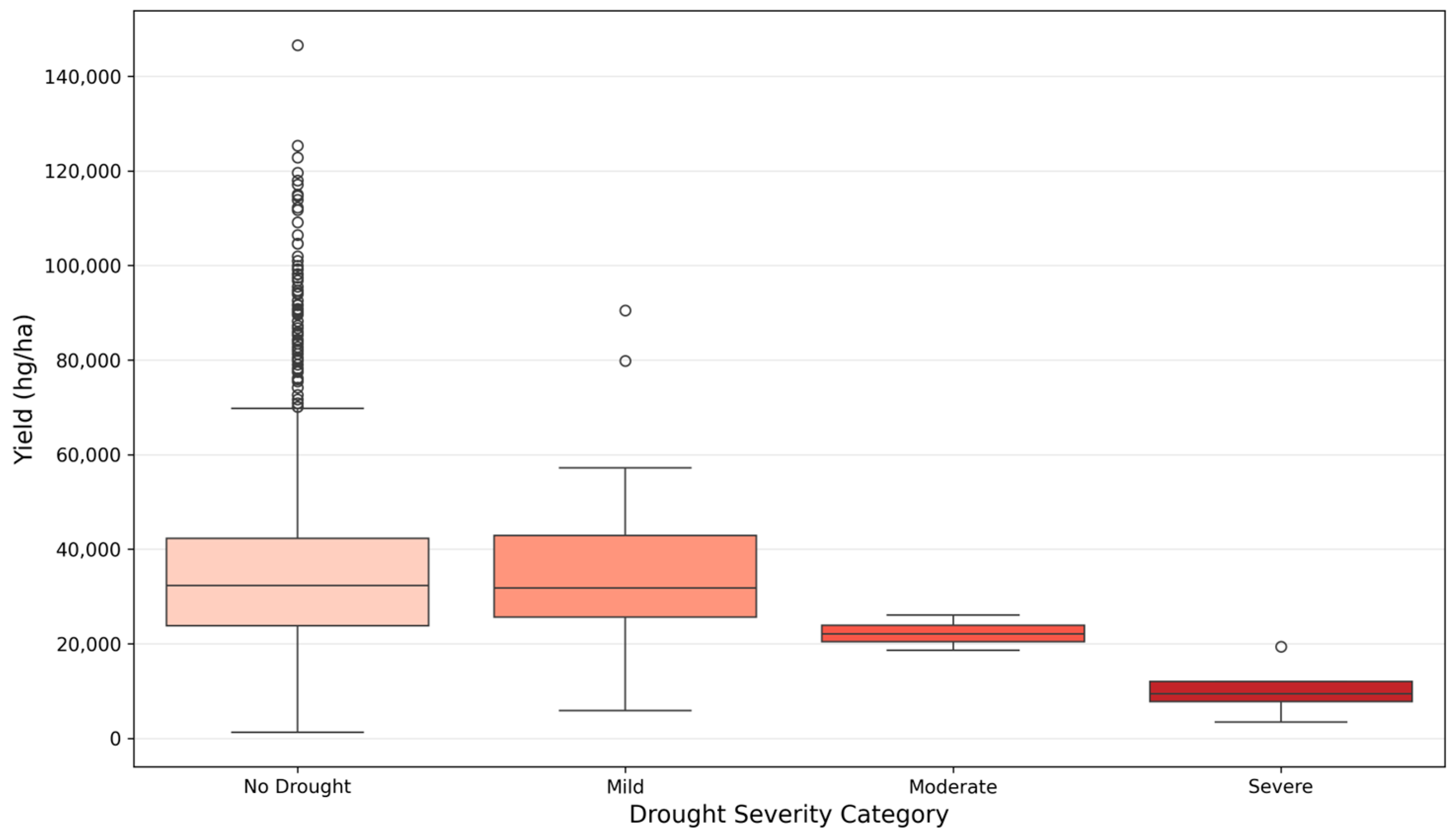

4.6. Drought Classification

4.7. Explainability via SHAP

5. Experimental Setup

5.1. Dataset Partitioning

- Random splitting maximizes the calibration set size for conformal prediction, ensuring robust coverage guarantees. Temporal holdout would reduce the available calibration samples, which could potentially compromise finite-sample validity.

- Random assignment assumes that samples are exchangeable despite potential spatial autocorrelation between neighboring countries. This may inflate performance metrics if geographic proximity induces residual correlation [68].

- The model learns from all years simultaneously, capturing both the technological trend index and specific climate patterns. True forecasting would require predicting future years that remained entirely unseen during the training process.

5.2. Model Configuration and Implementation

Hyperparameter Selection Strategy

- Default Parameters: Stable parameters with well-established defaults were adopted from standard library conventions. For example, a min_samples_split of 2 was used for decision trees, which allows full tree growth limited only by other specified constraints [70].

- Cross-Validation Tuning: Critical parameters affecting the bias–variance trade-off were optimized via 5-fold cross-validation on the training set. This included the Ridge regression penalty selected via RidgeCV, the gradient boosting learning rate chosen via grid search, and the GNN learning rate selected based on convergence stability.

- Literature-Informed Choices: Domain-specific parameters drew on prior work in the field. A GNN dropout rate of was selected following [27] for graph-based agricultural modeling. Bootstrap iterations were set at to balance variance reduction with computational cost, as prior research [71] demonstrated diminishing returns beyond 30 to 50 iterations for ensemble methods. Furthermore, the conformal coverage was set at for an 80% target, which is a standard choice balancing interval precision with reliability for agricultural decision support [71].

- Exploratory Analysis: Several parameters were determined through preliminary experiments on held-out validation data. Random forest and gradient boosting tree depths were tested across a range of 5, 6, 8, 10, and 12 to prevent overfitting while capturing interactions. Additionally, the number of trees varied between 50, 100, and 200 to balance accuracy saturation with total training time.

5.3. Baselines

- Ridge regression: Linear baseline with L2 regularization.

- RF-standalone: Single random forest (100 trees) without stacking.

- GB-standalone: Single gradient boosting machine (100 estimators).

- HSE-BQU (Uncalibrated): The proposed ensemble using raw percentile intervals, serving as an ablation study for the conformal calibration step.

5.4. Evaluation Metrics

- Regression accuracy: Coefficient of determination (R2), root mean squared error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE).

- Uncertainty quantification:

- ○

- Empirical coverage: The proportion of test samples falling within prediction intervals (Target: 80%).

- ○

- Interval width: Average size of the prediction bounds (narrower is better given valid coverage).

- Drought classification: Accuracy and class-wise confusion matrix.

6. Results

6.1. Overall Prediction Performance

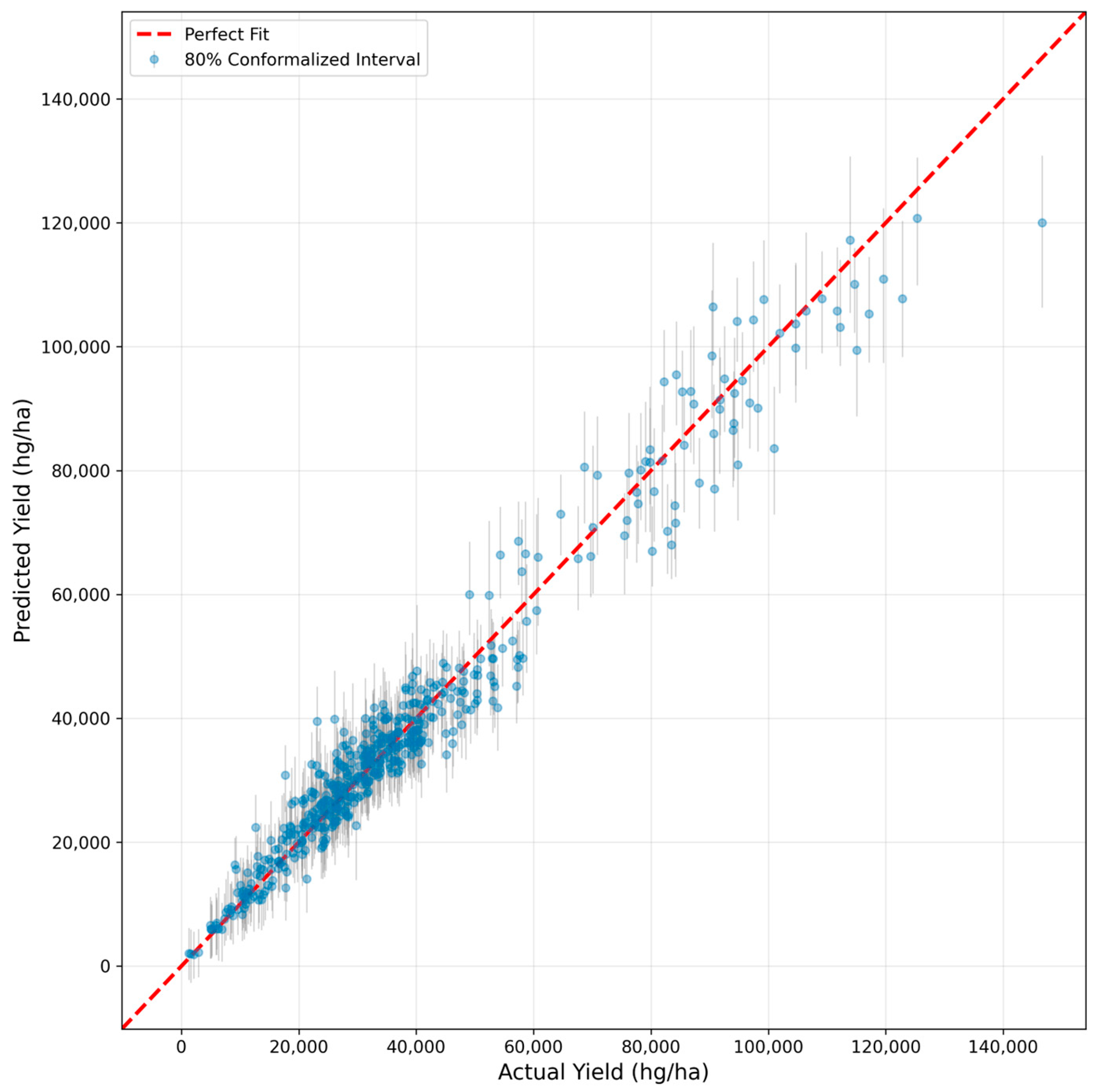

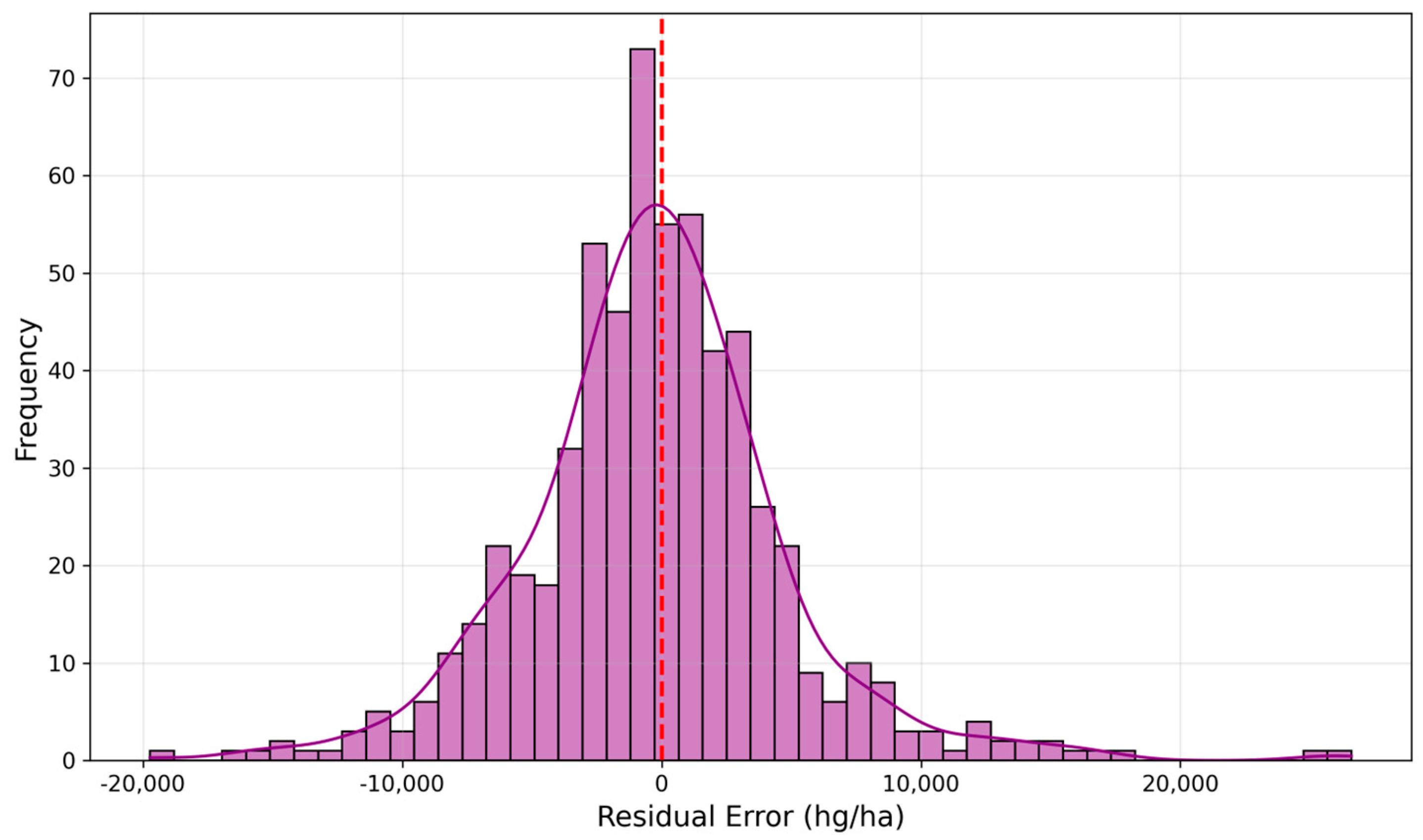

6.2. Prediction Accuracy Visualization

6.3. Uncertainty Assessment

6.4. Feature Importance and Explainability

6.5. Drought Risk Categorization for Decision Support

- Policy: Governments can utilize these categories to estimate production losses under various drought scenarios, facilitating more proactive food security planning.

- Insurance: Actuaries can use these verified severity thresholds to more accurately price weather-indexed insurance contracts.

- Farm Management: Real-time MSI monitoring, when combined with these discrete risk categories, allows for early irrigation interventions and more efficient resource management.

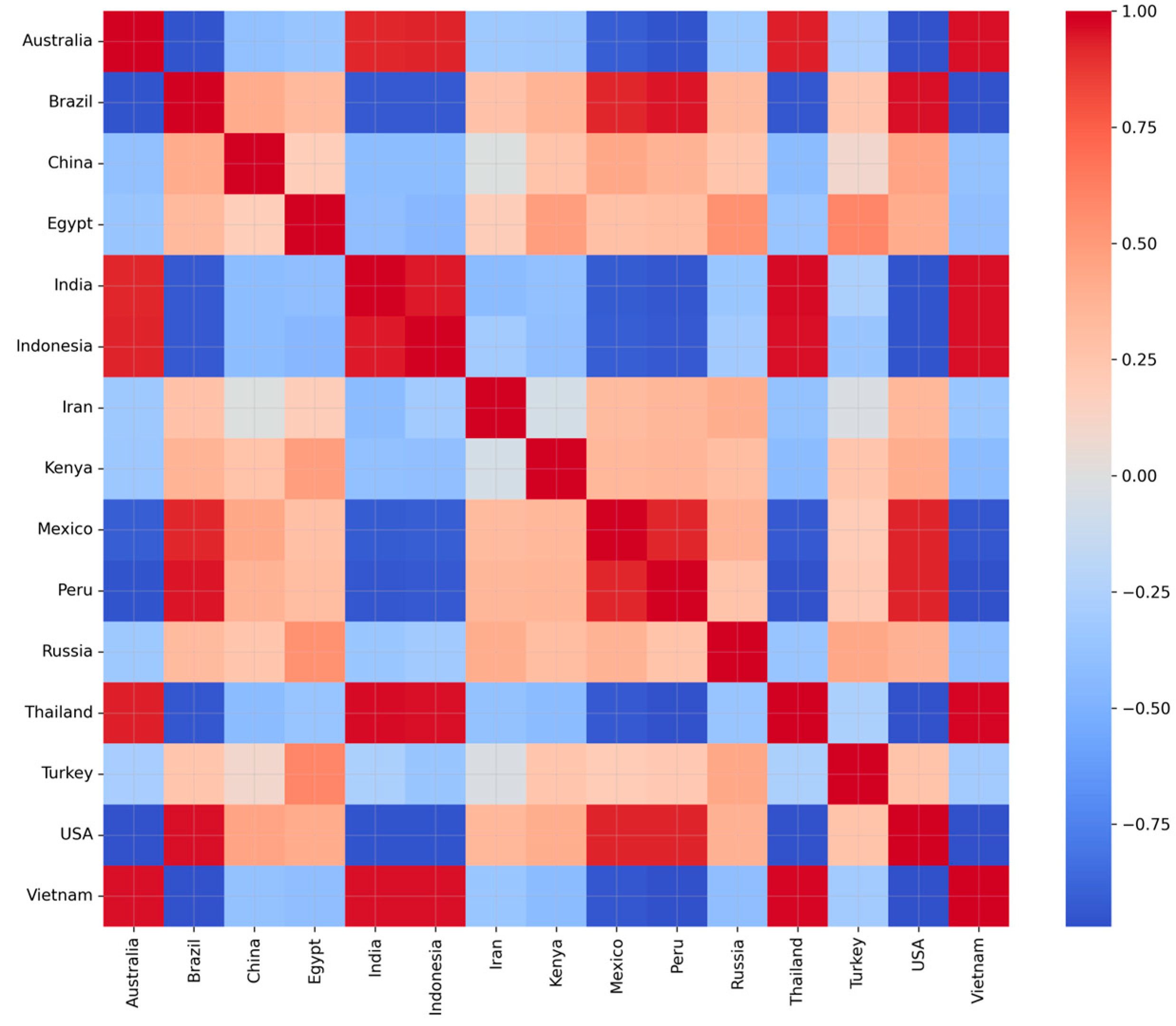

6.6. Teleconnection Analysis

- ▪

- Asian Monsoon Belt: A dense positive cluster is observed connecting India, Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam, with strong correlations of . These nations share common monsoon circulation dynamics, specifically the Southwest Monsoon and shifts in the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone, resulting in synchronized rainfall anomalies.

- ▪

- Trans-Pacific Connections: Strong positive correlations () exist between Australia and Indonesia, driven by the Walker circulation. Both regions typically experience dry conditions during El Niño and wet conditions during La Niña. Additionally, the Americas cluster comprising the USA, Mexico, and Peru shows moderate positive correlations (), likely influenced by the ENSO forcing in the Pacific and the North American monsoon.

- ▪

- Dipole Patterns: The matrix correctly identifies negative correlations that represent teleconnection dipoles. For instance, Brazil and India exhibit a correlation of . This reflects the known pattern where El Niño warming in the Pacific often triggers drought in Brazil while simultaneously enhancing monsoon variability in the Indian Ocean.

7. Ablation Studies

GNN Teleconnection Embeddings

8. Discussion

8.1. Key Findings and Hypothesis Validation

- The HSE-BQU framework achieves an of 0.9594, surpassing both random forest and gradient boosting baselines. This confirms that leveraging complementary model strengths through stacking enhances predictive performance.

- Conformalized intervals achieved 80.72% coverage against a target of 80%, compared to only 40.03% for the uncalibrated bootstrap. This validates that conformal prediction is critical for reliable risk management.

- The inclusion of the ENSO and NAO indices and GNN-derived spatial embeddings provides measurable signal improvements, offering a structured foundation for global spatial models.

- SHAP analysis confirms that crop type, rainfall, and climate suitability dominate predictions, aligning the model decisions with established agronomic theory.

8.2. Conformalized Uncertainty: Why It Matters

8.3. Value and Limitations of Graph-Based Spatial Modeling

8.4. Feature Importance and Technology Insights

8.5. Drought Classification Utility

- Policy: Governments can estimate potential production losses under drought scenarios to inform food security strategies.

- Insurance: Actuaries can price weather-indexed contracts based on verified drought severity levels.

- Farmers: Real-time drought monitoring systems combined with this classifier enable early irrigation interventions.

8.6. Practical Applications

8.7. Limitations and Future Research

- Country-level data masks sub-national heterogeneity. Future studies should employ field-scale or gridded data to enhance spatial resolution.

- Expanding the dataset to include pulses, fruits, and specialty crops would broaden the system’s utility. Additionally, including data prior to 1990 would improve multi-decadal oscillation modeling.

- The linear time-based technology index provides a parsimonious approximation of agricultural productivity gains from improved varieties, mechanization, and agronomy. However, this deterministic encoding has limitations. It assumes uniform technological progress across all countries and crops, which oversimplifies heterogeneous development patterns. Additionally, the linear form may not capture acceleration or saturation in yield gains, and its perfect correlation with the year creates potential for temporal confounding if not carefully interpreted. Future work should explore country-specific or non-linear technology curves.

- Conformal prediction assumes test data are exchangeable with calibration data. Climate change induces non-stationarity, potentially violating this assumption. Adaptive conformal prediction could mitigate this risk by adjusting to shifting climate states.

- Integrating soil quality, management practices, and pest pressure through satellite imagery could further refine predictions, though this would require more complex convolutional architectures.

9. Conclusion and Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Acronym | Full Form |

| HSE-BQU | Heterogeneous Stacked Ensemble with Bootstrap Uncertainty Quantification |

| CP | Conformal Prediction |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| ENSO | El Niño–Southern Oscillation |

| NAO | North Atlantic Oscillation |

| GDD | Growing Degree Days |

| MSI | Moisture Stress Index |

| CSS | Climate Suitability Score |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

References

- FAO’s Director-General on How to Feed the World in 2050. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2009, 35, 837–839. [CrossRef]

- Alexandratos, N.; Bruinsma, J. World agriculture towards 2030/2050: The 2012 revision. Res. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizumi, T.; Luo, J.; Challinor, A.J.; Sakurai, G.; Yokozawa, M.; Sakuma, H.; Brown, M.E.; Yamagata, T. Impacts of El Niño Southern Oscillation on the global yields of major crops. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, D.K.; Gerber, J.S.; MacDonald, G.K.; West, P.C. Climate variation explains a third of global crop yield variability. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heino, M.; Puma, M.J.; Ward, P.J.; Gerten, D.; Heck, V.; Siebert, S.; Kummu, M. Two-thirds of global cropland area impacted by climate oscillations. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceglar, A.; Turco, M.; Toreti, A.; Doblas-Reyes, F.J. Linking crop yield anomalies to large-scale atmospheric circulation in Europe. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017, 240–241, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Bai, J.; Li, Z.; Ortiz-Bobea, A.; Gomes, C.P. A GNN-RNN Approach for Harnessing Geospatial and Temporal Information: Application to Crop Yield Prediction. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual, 22 February–1 March 2022; Volume 36, pp. 11873–11881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulos, A.N.; Bates, S. A Gentle Introduction to Conformal Prediction and Distribution-Free Uncertainty Quantification. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.07511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.; Lee, S. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.07874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrumbelj, E.; Kononenko, I. Explaining prediction models and individual predictions with feature contributions. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2014, 41, 647–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Bagging Predictors. Mach. Learn. 1996, 24, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.02907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Xu, X.; Xie, H.; Chen, P.; Wang, C.; Jin, Y.; Tong, X.; Xiao, C. A Modified Shape Model Incorporating Continuous Accumulated Growing Degree Days for Phenology Detection of Early Rice. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przeździecki, K.; Zawadzki, J. Assessing Moisture Content and Its Mitigating Effect in an Urban Area Using the Land Surface Temperature–Vegetation Index Triangle Method. Forests 2023, 14, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, A.A.; Srivatsa, A.; Ashwitha, A.; Monteiro, A.; Gajakosh, C. Crop Yield Prediction to Achieve Precision Agriculture using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Mobile Networks and Wireless Communications (ICMNWC), Tumkur, India, 2–3 December 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaki, S.; Wang, L. Crop Yield Prediction Using Deep Neural Networks. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talaat, F.M. Crop yield prediction algorithm (CYPA) in precision agriculture based on IoT techniques and climate changes. Neural Comput. Applic 2023, 35, 17281–17292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Suman; Prasad, D. Crop Yield Prediction using Remote Sensing: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Computing Applications (ICCICA), Samalkha, India, 23–24 May 2024; Volume 1, pp. 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heino, M.; Guillaume, J.H.A.; Müller, C.; Iizumi, T.; Kummu, M. A multi-model analysis of teleconnected crop yield variability in a range of cropping systems. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2020, 11, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motha, R.P. Implications of climate change on long-lead forecasting and global agriculture. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2007, 58, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reboita, M.S.; Ambrizzi, T.; Crespo, N.M.; Dutra, L.M.M.; Ferreira, G.W.d.S.; Rehbein, A.; Drumond, A.; da Rocha, R.P.; Souza, C.A.d. Impacts of teleconnection patterns on South America climate. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2021, 1504, 116–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, R.; Vijverberg, S.; Van Loon, A.F.; Aerts, J.; Coumou, D. Persistent La Niñas drive joint soybean harvest failures in North and South America. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2023, 14, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.; Khouakhi, A.; Waine, T.W. The impact of weather patterns on inter-annual crop yield variability. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 177181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanthanaporn, U.; Supit, I.; Chaowiwat, W.; Hutjes, R.W.A. Skill of rice yields forecasting over Mainland Southeast Asia using the ECMWF SEAS5 ensemble prediction system and the WOFOST crop model. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 351, 110001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Liu, W.; Huang, H. A Temporal–Geospatial Deep Learning Framework for Crop Yield Prediction. Electronics 2024, 13, 4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, F.; Liu, C.; Zhang, D.; Lu, T.; Zhang, L.; et al. Maize yield prediction with trait-missing data via bipartite graph neural network. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1433552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Singh, A. Agri-GNN: A Novel Genotypic-Topological Graph Neural Network Framework Built on GraphSAGE for Optimized Yield Prediction. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.13037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, F.L.; Devi, T.; Deepa, N. Enhanced Crop Yield Prediction in Agriculture Using an Optimized Edge Enhancement Oriented Graph Convolutional Network. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Engineering Innovations and Technologies (ICoEIT), Bhopal, India, 4–5 July 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1393–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Zhai, X.; She, T.; Liu, X.; Hong, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q. Winter Wheat Yield Prediction Based on the ASTGNN Model Coupled with Multi-Source Data. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Jägermeyr, J.; O’Leary, G.J.; Wallach, D.; Ruane, A.C.; Feng, P.; Li, L.; Liu, D.L.; Waters, C.; Yu, Q.; et al. Pathways to identify and reduce uncertainties in agricultural climate impact assessments. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokoohaki, H.; Kivi, M.S.; Martinez-Feria, R.; Miguez, F.E.; Hoogenboom, G. A comprehensive uncertainty quantification of large-scale process-based crop modeling frameworks. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 84010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrispell, J.C.; Jenkins, E.W.; Kavanagh, K.R.; Parno, M.D. Characterizing Prediction Uncertainty in Agricultural Modeling via a Coupled Statistical–Physical Framework. Modelling 2021, 2, 753–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakeman, A.J.; Jakeman, J.D. An Overview of Methods to Identify and Manage Uncertainty for Modelling Problems in the Water–Environment–Agriculture Cross-Sector. In Agriculture as a Metaphor for Creativity in All Human Endeavors, Proceedings of the FMfI 2016, Brisbane, Australia, 21–23 November 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 28, pp. 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mae, Y.; Kumagai, W.; Kanamori, T. Uncertainty propagation for dropout-based Bayesian neural networks. Neural Netw. 2021, 144, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Rao, S.; Hassaine, A.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Canoy, D.; Salimi-Khorshidi, G.; Mamouei, M.; Lukasiewicz, T.; Rahimi, K. Deep Bayesian Gaussian processes for uncertainty estimation in electronic health records. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, G.; Vovk, V. A tutorial on conformal prediction. arXiv 2007, arXiv:0706.3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, R.F.; Candès, E.J.; Ramdas, A.; Tibshirani, R.J. Conformal prediction beyond exchangeability. Ann. Stat. 2023, 51, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, I.; Candès, E. Adaptive Conformal Inference Under Distribution Shift. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.00170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.; Emam, A.; Leonhardt, J.; Roscher, R. Enhancing decision support in crop production: Analyzing conformal prediction for uncertainty quantification. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaffran, M.; Dieuleveut, A.; Féron, O.; Goude, Y.; Josse, J. Adaptive Conformal Predictions for Time Series. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.07282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hyndman, R.J. Online conformal inference for multi-step time series forecasting. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.13115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, V.; Bianchi, F.M.; Anfinsen, S.N. Ensemble Conformalized Quantile Regression for Probabilistic Time Series Forecasting. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 9014–9025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkem, Y.; Biswas, S.K.; Varanasi, A. Role of Explainable AI in Crop Recommendation Technique of Smart Farming. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2025, 17, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, D.G.; Balachandra, M.; Kamath, R. Explainable AI in agriculture: Review of applications, methodologies, and future directions. Eng. Res. Express 2025, 7, 32202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, M. Enhancing Agricultural Decision-Making through an Explainable AI-Based Crop Recommendation System. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Signal Processing and Advance Research in Computing (SPARC), Lucknow, India, 12–13 September 2024; Volume 1, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisten, M.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Olusanya, M.O. Explainable Artificial Intelligence Model for Predictive Maintenance in Smart Agricultural Facilities. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 24348–24367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distante, D.; Albanello, C.; Zaffar, H.; Faralli, S.; Amalfitano, D. Artificial intelligence applied to precision livestock farming: A tertiary study. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 11, 100889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adadi, A.; Berrada, M. Peeking Inside the Black-Box: A Survey on Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). IEEE Access 2018, 6, 52138–52160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, O.; Kok, I.; Ozdemir, S. AgroXAI: Explainable AI-Driven Crop Recommendation System for Agriculture 4.0. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), Washington, DC, USA, 15–18 December 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 7208–7217. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, R.N.V.J.; Rayanoothala, P.S.; Sree, R.P. Next-gen agriculture: Integrating AI and XAI for precision crop yield predictions. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1451607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, Q. Soil temperature prediction based on explainable artificial intelligence and LSTM. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1426942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malashin, I.; Tynchenko, V.; Gantimurov, A.; Nelyub, V.; Borodulin, A.; Tynchenko, Y. Predicting Sustainable Crop Yields: Deep Learning and Explainable AI Tools. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myakala, P.K.; Jonnalagadda, A.K. Explainable AI for Sustainability: Bridging Trust, Ethics, and Accountability. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Recent Advances in Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Development (RAISD 2025); Atlantis Press (Zeger Karssen): Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2025; Volume 196. [Google Scholar]

- Abekoon, T.; Sajindra, H.; Rathnayake, N.; Ekanayake, I.U.; Jayakody, A.; Rathnayake, U. A novel application with explainable machine learning (SHAP and LIME) to predict soil N, P, and K nutrient content in cabbage cultivation. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 11, 100879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Falluji, R.A.; Albahar, M.A. Enhancing green AI through explainable deep learning-based multi-model for automated rice leaf disease classification. Discov. Comput. 2025, 28, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallik, S.; Chakraborty, A.; Podder, K.; Talukdar, S.; Rahman, A.; Mishra, U. Enhancing soil moisture prediction with explainable AI: Integrating IoT and multi-sensor remote sensing data through soft computing. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 180, 113406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAOSTAT Statistical Database. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Harris, I.; Osborn, T.J.; Jones, P.; Lister, D. Version 4 of the CRU TS monthly high-resolution gridded multivariate climate dataset. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBB Columbia Basin Bulletin-The Columbia Basin Bullet: NOAA Climate Prediction Center Updated El Nino Forecast: Northwest on Track for Warm, Dry Winter. Columbia Basin Bulletin [BLOG]. 2024. Available online: https://columbiabasinbulletin.org/el-nino-in-place-for-winter-first-time-in-four-years-drier-than-average-across-northern-tier/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Hively, W.D.; Lee, S.; Sadeghi, A.M.; McCarty, G.W.; Lamb, B.T.; Soroka, A.; Keppler, J.; Yeo, I.Y.; Moglen, G.E. Estimating the effect of winter cover crops on nitrogen leaching using cost-share enrollment data, satellite remote sensing, and Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) modeling. J. Soil. Water Conserv. 2020, 75, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhag, M.; Bahrawi, J.A. Soil salinity mapping and hydrological drought indices assessment in arid environments based on remote sensing techniques. Geosci. Instrum. Methods Data Syst. 2017, 6, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, Z.D.; Willard, F.; Ge, C.; Rodriguez, C.; Bergin, M.; Carlson, D. Estimating the effects of vegetation and increased albedo on the urban heat island effect with spatial causal inference. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vovk, V.; Gammerman, A.; Shafer, G. Algorithmic Learning in a Random World, 2nd ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rossellini, R.; Barber, R.F.; Willett, R. Integrating Uncertainty Awareness into Conformalized Quantile Regression. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.08693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulos, A.N.; Bates, S. Conformal Prediction: A Gentle Introduction. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 2023, 16, 494–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badea, T.; Dumitrescu, B. Haar-Laplacian for Directed Graphs. IEEE Trans. Signal Inf. Process. Over Netw. 2025, 11, 1238–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyapustin, A.I.; Gourlet-Fleury, S.; Mortier, F.; Bayol, N.; Pélissier, R.; Rejou-Mechain, M.; Barbier, N.; Ploton, P.; Picard, N.; Rossi, V.; et al. Spatial validation reveals poor predictive performance of large-scale ecological mapping models. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, A. Choosing blocks for spatial cross-validation: Lessons from a marine remote sensing case study. Front. Remote Sens. 2025, 6, 1531097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Chaudhari, O.; Chandra, R. A review of ensemble learning and data augmentation models for class imbalanced problems: Combination, implementation and evaluation. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2024, 244, 122778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwaniuk, M.; Jarosz, M.; Borycki, B.; Jezierski, B.; Cwalina, J.; Kaźmierczak, S.; Mańdziuk, J. The Impact of Bootstrap Sampling Rate on Random Forest Performance in Regression Tasks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.13952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Component | Specification |

|---|---|---|

| HSE-BQU | Ensemble | Bootstrap Iterations B = 30; Meta-Learner: Ridge (L2 selected via CV) |

| Base: Random Forest | 50 trees, max_depth = 12, min_samples_split = 2, max_features = √d | |

| Base: Grad. Boost | 50 estimators, max_depth = 6, learning_rate = 0.1 | |

| Uncertainty | Conformal (CQR) | Target Coverage 1 − α = 80%; Method: Higher quantile correction |

| GNN | Structure | 2-Layer GCN; Hidden Dim = 64; Dropout = 0.2; Edge Threshold τ = 0.5 |

| Training | Optimizer: Adam (η = 0.01); Epochs: 200; Loss: MSE | |

| Implementation | Software | Python 3.11, Scikit-learn 1.3, PyTorch Geometric 2.4, SHAP 0.42 |

| Hardware | Intel Core Ultra (14 cores), 16 GB RAM. Training time ≈ 15 min. |

| Model | R2 | RMSE (hg/ha) | MAE (hg/ha) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ridge Regression | 0.8721 | 8653 | 6124 |

| RF-Standalone | 0.9412 | 5874 | 4231 |

| GB-Standalone | 0.9385 | 6012 | 4389 |

| HSE-BQU | 0.9594 | 4882 | 3487 |

| Method | Target Coverage | Achieved Coverage | Avg Interval Width (hg/ha) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bootstrap (Uncalibrated) | 80% | 40.03% | 4790 |

| HSE-BQU-CP (Conformalized) | 80% | 80.72% | 11,161 |

| Experiment | Model Variant | R2 | RMSE (hg/ha) | Coverage/MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Calibration | Uncalibrated Bootstrap | 0.9594 | 4882 | 40.03% (Cov) |

| HSE-BQU-CP (Proposed) | 0.9594 | 4882 | 80.72% (Cov) | |

| 2. Features | No Teleconnections (w/o ENSO/NAO) | 0.9571 | 5012 | - |

| Full Model | 0.9594 | 4882 | - | |

| 3. Ensemble Size | B = 10 Iterations | 0.9566 | 5124 | - |

| B = 30 Iterations (Selected) | 0.9587 | 4882 | - | |

| B = 50 Iterations | 0.9587 | 4831 | - | |

| 4. GNN Embeddings | Baseline + Indices | 0.9663 | 4534 | 3005 (MAE) |

| With GNN Embeddings (256-d) | 0.9668 | 4500 | 2993 (MAE) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mahmood, S.; Hasan, R.; Ahmad, S. HSE-GNN-CP: Spatiotemporal Teleconnection Modeling and Conformalized Uncertainty Quantification for Global Crop Yield Forecasting. Information 2026, 17, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17020141

Mahmood S, Hasan R, Ahmad S. HSE-GNN-CP: Spatiotemporal Teleconnection Modeling and Conformalized Uncertainty Quantification for Global Crop Yield Forecasting. Information. 2026; 17(2):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17020141

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahmood, Salman, Raza Hasan, and Shakeel Ahmad. 2026. "HSE-GNN-CP: Spatiotemporal Teleconnection Modeling and Conformalized Uncertainty Quantification for Global Crop Yield Forecasting" Information 17, no. 2: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17020141

APA StyleMahmood, S., Hasan, R., & Ahmad, S. (2026). HSE-GNN-CP: Spatiotemporal Teleconnection Modeling and Conformalized Uncertainty Quantification for Global Crop Yield Forecasting. Information, 17(2), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17020141