Behind the Screens: A Systematic Literature Review on Barriers and Mitigating Strategies for Combating Cyberbullying

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. CB Forms

- Cyberstalking: Sending hurtful messages via online communication [31].

- Denigration: Circulating false information to harm someone’s reputation [32].

- Exclusion: Removing an individual from an online social group [35].

- Frapping: Utilising someone else’s social media accounts and pretending to be the actual owner while posting on their behalf, including unsuitable content. This is performed solely to make others believe that the owner has shared inappropriate material [35].

- Harassment: Victimisation through sending insulting, rude, and offensive texts [35].

- Masquerade: Disguising themselves as another person or, in other terms, concealing their true identity [38].

- Trolling: Deliberately provoking people to argue or fight through negative communication [5].

1.2. Topic Conceptualisation

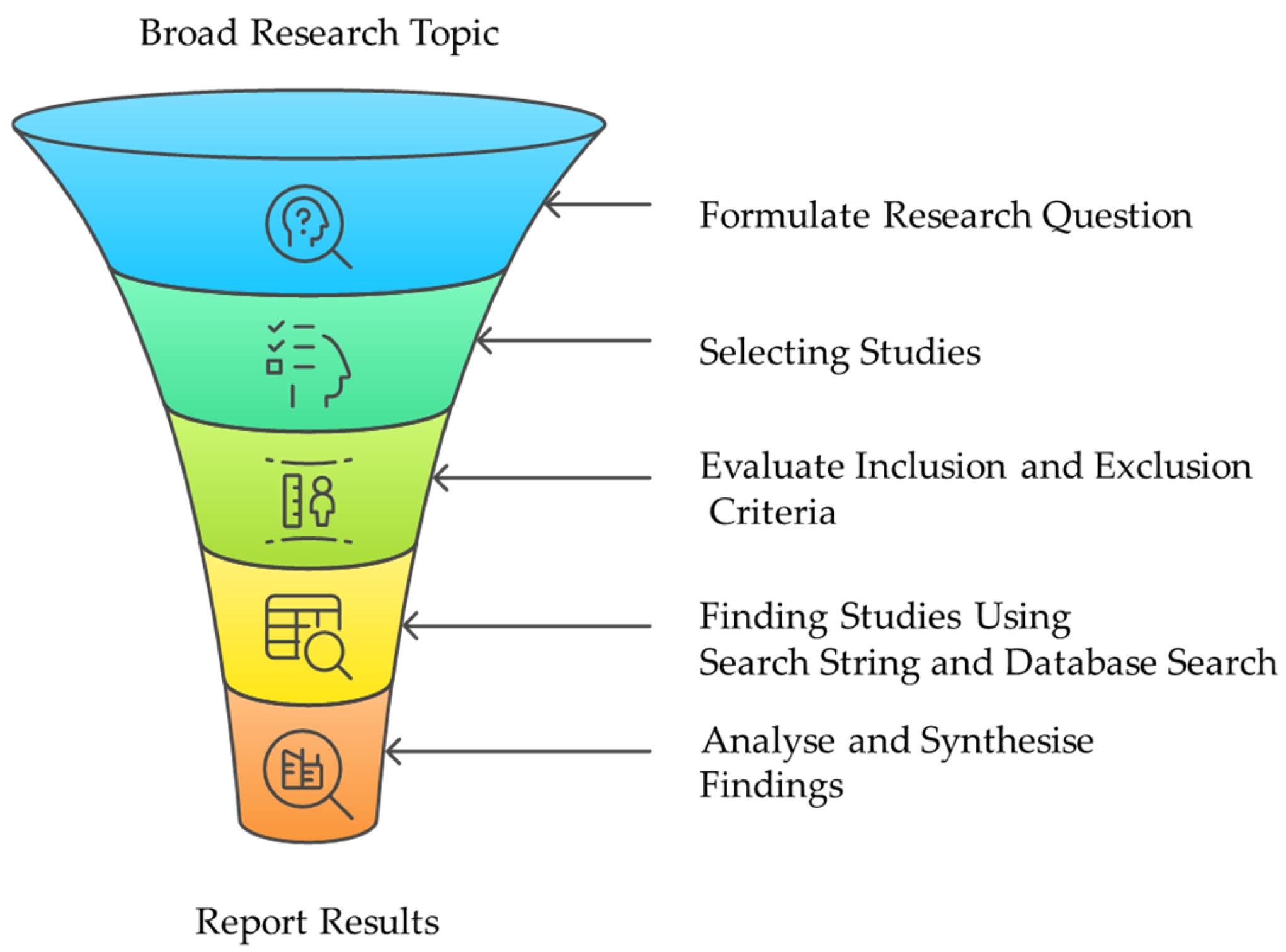

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phase 1: Planning the Review

2.1.1. Formulating Research Questions

- RQ.1: What are the various forms of CB experienced by adults?

- RQ.2: What are the significant barriers and challenges in effectively addressing and responding to CB in adults, as identified in the existing literature?

- RQ.3: What prevention and mitigation strategies have been studied to reduce CB incidents among adults?

- RQ.4: How do these barriers hinder the effectiveness of prevention and mitigation strategies for CB in adults?

- Objective 1: To explore the multiple forms of CB encountered by adults.

- Objective 2: To identify the key barriers and challenges that hinder efforts to address and respond to CB in adults.

- Objective 3: To examine the existing CB prevention and mitigation strategies for adults as reported in the literature.

- Objective 4: To analyse how different barriers hinder the effectiveness of prevention and mitigation strategies, assess their impact, and suggest solutions for the improved implementation of CB policies for adults.

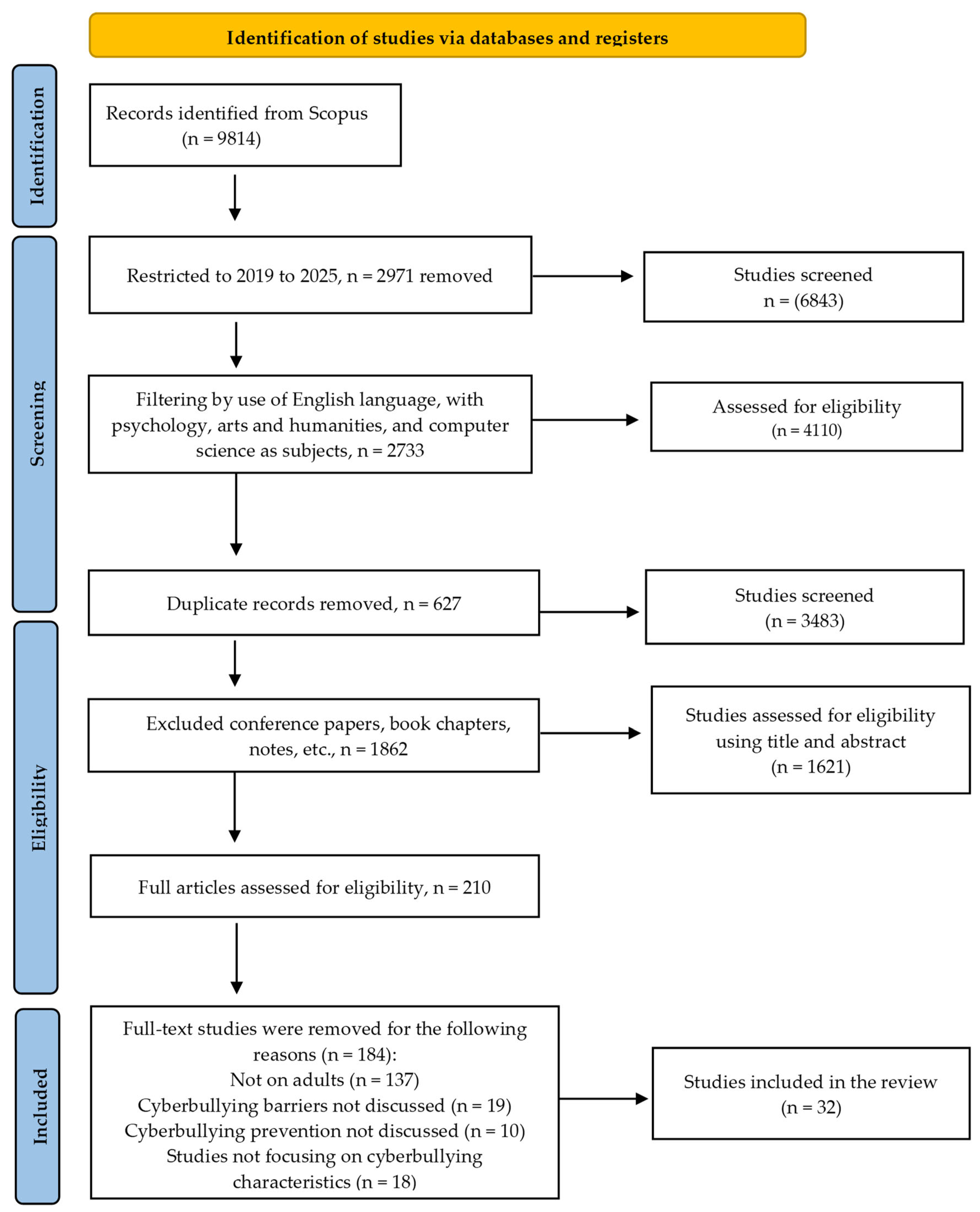

2.1.2. Search Strategy

2.1.3. Establishing Data Source

- Range of Research Paper

- 2.

- Inclusion Criteria

- Studies published from January 2019 to January 2025.

- Studies that were published only in journal articles.

- Studies conducted on CB.

- Studies published in the English language.

- The study should have addressed barriers or challenges and/or prevention or mitigation strategies to address CB.

- Studies where keywords (CB among adults, CB among university students, CB among college students, CB in higher education, and CB in workplaces) were found in the title, abstract, and keywords.

- 3.

- Exclusion Criteria

- Studies presented as notes or at conferences, seminars, and symposiums.

- Book chapters, news articles, short paper summaries, abstracts, and incomplete studies.

- Repeated/duplicated articles found from the defined data sources and journals.

- Studies not reported in the English language.

- Studies that did not match the quality criteria.

2.2. Phase 2: Conducting the Review

2.2.1. Study Selection

2.2.2. Quality Assessment

2.2.3. Data Extraction

2.2.4. Validity Determination Process

2.3. Phase 3: Reporting the Review

3. Results

3.1. Forms of CB

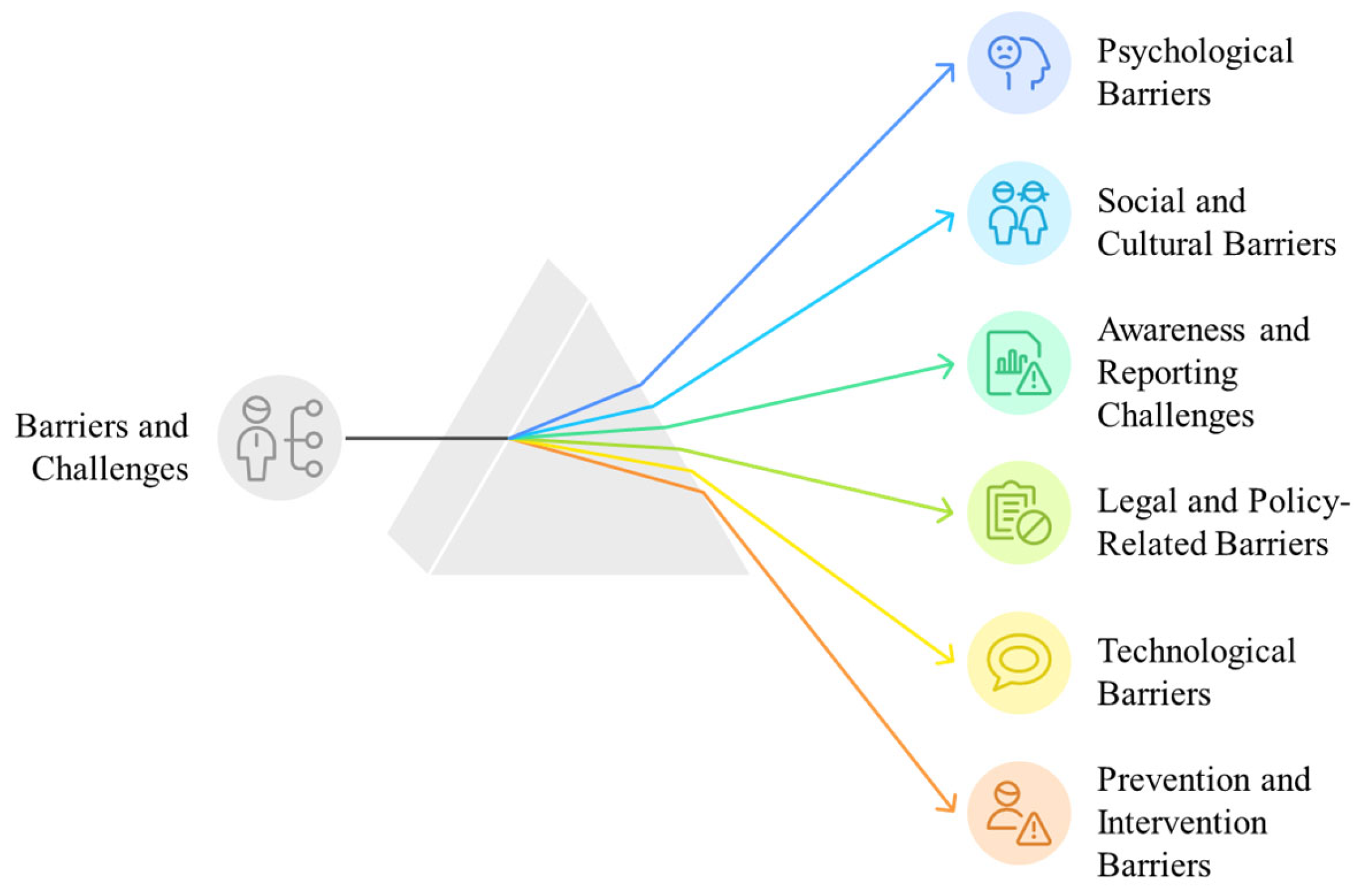

3.2. Barriers and Challenges Identified

3.2.1. Psychological Barriers

3.2.2. Social and Cultural Barriers

3.2.3. Awareness and Reporting Challenges

3.2.4. Legal and Policy-Related Barriers

3.2.5. Technological Barriers

3.2.6. Intervention and Prevention Barriers

3.3. Prevention Strategies Identified

3.3.1. Education and Awareness

3.3.2. Behavioural Strategies

3.3.3. Policy and Legal Measures

3.3.4. Technological Interventions

3.3.5. Support Systems

3.3.6. Supervision

3.3.7. Intervention Mechanisms

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Future Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CB | Cyberbullying |

| SLR | Systematic literature review |

| ICTs | Information and communication technologies |

| EDV | Electronic dating violence |

| CSMS | Cyberbullying in Social Media Scale |

| N/A | Not Available |

Appendix A

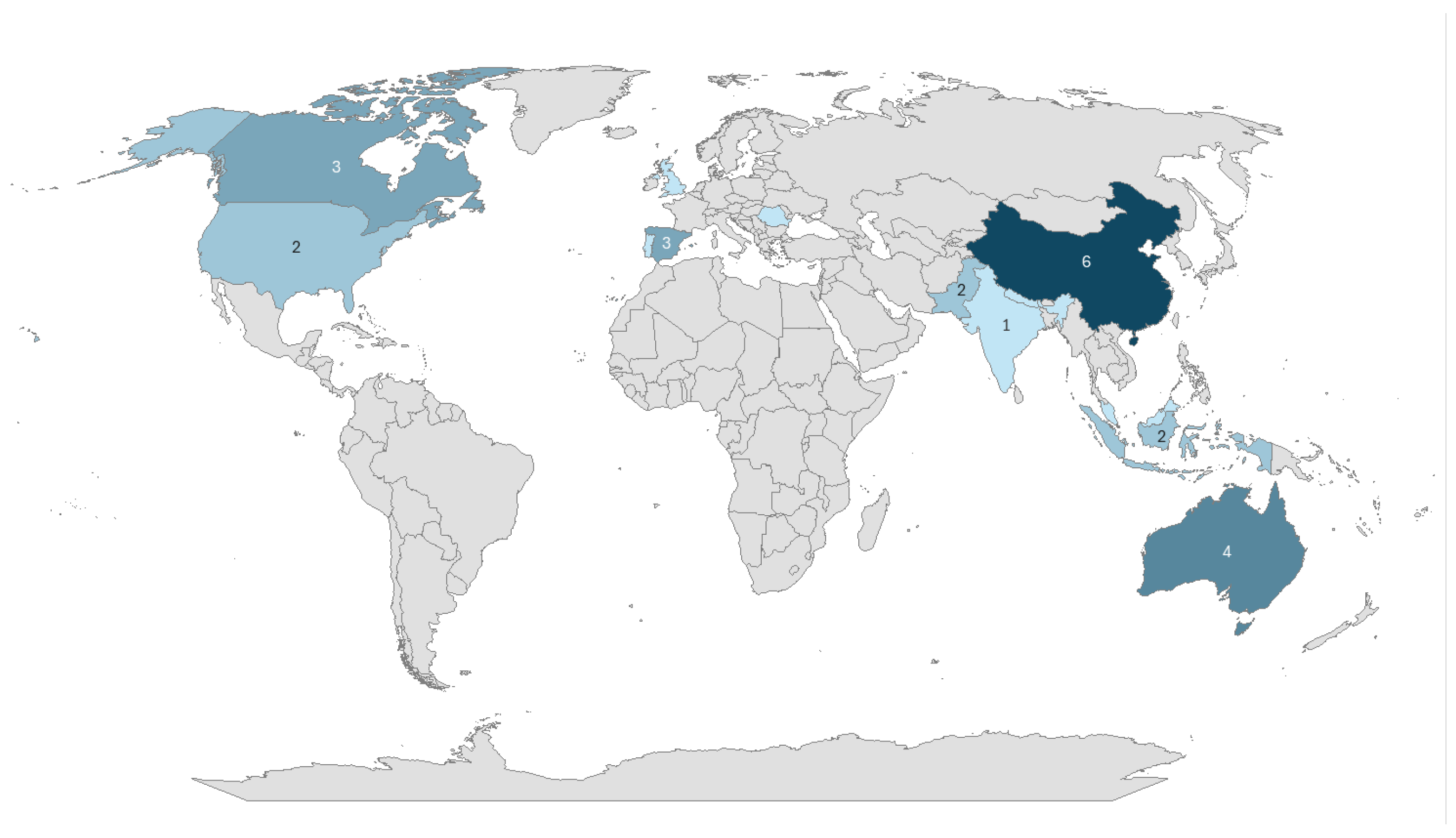

| No. | Source | Year | Country | Methodology | Gender | Participants | Age (Years) | Forms of Cyberbullying (CB) | Barriers and Challenges in Addressing CB | Prevention of CB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | [62] | 2023 | China | Quantitative | Males Females | 845 College Students | 18.7 (Avg) | Exploitative CB | -Psychological and Behavioural Risk Factors -Gender Differences -Cultural Context | -Education on Risks of Self-Disclosure -Targeted Interventions for Males -Leveraging Cultural Context -Promoting Social Support -Culturally Sensitive Approaches |

| 2. | [75] | 2020 | Canada | Qualitative | N/A | 1925 Undergraduates | N/A | Deceptive CB | -Lack of Awareness -Anonymity -Policy Gaps -Victim Blaming -Cultural Norms -Reporting Mechanisms -Bystander Intervention -Technological Solutions | -Awareness and Education -Policy Development -Protecting Privacy -Technology-Based Solutions -Empowering Better Choices and Responses -University Culture -Disciplinary Measures |

| 3. | [74] | 2021 | United Kingdom | Qualitative | Comments from 34 Popular Female UK Lifestyle Influencers’ YouTube Channels | 4,626,706 Comments from 2,062,265 Users | N/A | The General Context of Bullying and CB | -Self-Blame -Reluctance to Seek Formal Support | -Supportive Online Communities -Encouraging Empathy and Support -Public Discussions by Influencers -Generalisation and Abstraction -Criticising Bullies |

| 4. | [53] | 2023 | Australia | Quantitative | Males Females | 270 Australian University Students | 18–29 | Public Shaming CB | -Empathic Distress -Empathic Anger -Compassion -Gender Differences -Perceived Costs of Defending | -Empathy Training -Channelling Empathic Anger -Compassion Training -Gender-Specific Approaches -Reducing Perceived Costs of Defending |

| 5. | [73] | 2024 | China | Quantitative | Females | 1673 College Students | 16+ | CB Behaviours | -Anonymity and Virtuality -Lack of Positive Coping Strategies -Emotional Coping Strategies | -Promoting Positive Coping Strategies -Encouraging Support-Seeking -Combating Online Rumours and Biased News -Government and Media Collaboration -Reducing Emotional Coping |

| 6. | [67] | 2024 | Portugal | Quantitative | Females Heterosexual Bisexual Gay or Lesbian | Study 1: 485 Students Study 2: 952 Students | 16–34 13–30 | Multi-Faceted CB | -High Prevalence -Psychological Distress -Lack of Awareness -Social and Family Support -Minority Groups -Bystander Intervention -Overlap with Traditional Bullying | -Social Support -Awareness Programmes -Bystander Intervention -Targeted Interventions for Vulnerable Groups -Comprehensive Bullying Prevention Programmes -Teacher and School Involvement -Promoting Positive Online Behaviour |

| 7. | [76] | 2020 | Austria | Qualitative | N/A | 61 College Students | N/A | Malicious CB | -Escalation and Intensity -Role Switching -Psychological Impact -Legal and Ethical Issues -Lack of Immediate Support -Interconnected Spaces | -Legal Awareness -Co-Designing Solutions -Promoting Empathy and Respect -Digital Platforms’ Role (Emergency Button) |

| 8. | [77] | 2020 | India | Quantitative | N/A | 365 Participants | 15–25 | CB in General | -Over-Reliance on Security Measures -Gender Differences -Age Factor -Family and Institutional Control -Automatic Monitoring -Regulatory and Legal Norms -Cultural and Demographic Differences -Response Rate and Data Collection -Perception-Based Study | -Targeted Prevention and Intervention -Community and Institutional Supervision -Awareness Campaigns -Security Education -Monitoring and Reporting -Regulatory Framework -Health-Related Messages -Public Awareness -Toll-Free Helpline |

| 9. | [63] | 2020 | Spain | Quantitative | Males Females | 1282 Students | 18–46 | Psychological CB | -Emotional Problems -University Adaptation -Lack of Awareness and Reporting -Complex Relationships -Institutional Climate | -Addressing Emotional Problems (Implementing Screening Systems to Detect Emotional Distress) -Enhancing University Adaptation -Developing Emotional Intelligence -Creating a Positive Institutional Climate -Promoting Social Skills and Peer Relationships -Raising Awareness and Education -Encouraging Reporting and Intervention |

| 10. | [64] | 2023 | Nepal | Qualitative | Males Females | 20 Participants | 26–41 | Workplace CB | -Lack of Awareness and Sensitivity -Inadequate Legal Framework -Administrative Failure -Fear and Social Stigma -Digital Literacy -Lack of Effective Coping Mechanism | -Awareness and Education -Training for Teachers -Support Systems -Administrative Action -Filtering and Privacy Settings -Ignoring and Deactivating Accounts -Changing Workplaces -Family’s Involvement -Collaborative Efforts |

| 11. | [54] | 2020 | Romania | Qualitative | Males Females | 108 Psychologists and CB Counselling Experts | N/A | Aggressive and Sexual CB | -Convincing Victims to Speak Up -Regaining Self-Confidence -Low Reporting Rates -Lack of Clear Conceptual Boundaries -Complexity of Prevention Programmes -Digital Literacy -Family Involvement -Online Counselling | -Digital Literacy Courses -Family Involvement -Online Programmes -Mandatory and Permanent Programmes -Student Involvement -Counselling and Support -Online Counselling Platforms -Information Campaigns -Teacher Responsibilities |

| 12. | [55] | 2023 | China | Quantitative | Males Females | 269 College Students | 18–25 | Social Anxiety CB | -Impact on Mental Health -Appearance Anxiety -Self-Esteem Issues -Gender Differences -Lack of Direct Predictive Effect | -Family Involvement -Educational Interventions -Encouraging Positive Self-Esteem -Awareness and Training -Support Systems |

| 13. | [72] | 2021 | Jordan | Qualitative | Females | 104 Undergraduate Students | 18–20 | Electronic Dating Violence (EDV) | -Gender Stereotypes and Social Norms -Fear of Repercussions -Lack of Support Systems -Cultural and Social Context -Technological Vulnerabilities Economic and Family Circumstances | -Awareness and Education -Support Systems -Technical Measures -Legal and Policy Interventions -Coping Strategies (Teaching Women Coping Mechanisms to Deal With Dating Violence, Such as Seeking Emotional Support, Adjusting Expectations, and Utilising Distractions Like Shopping, Exercise, and Sleeping; Encouraging Victims to Report All Types of Abuse and Not Remain Silent Due to Fear of Shame and Social Stigma) |

| 14. | [68] | 2023 | Canada | Qualitative | Mixed Males Females Non-Binary Not Listed Prefer Not to Say | 1073 Participants | 18–25 | Bystander-Influenced CB | -Distraction -Ambiguity -Relationship -Pluralistic Ignorance -Diffusion of Responsibility -Lack of Competence -Audience Inhibition -Costs Exceed Rewards | -Educational Programmes -Empowering Bystanders -Promoting Collective Responsibility -Encouraging Private Interventions -Addressing Barriers |

| 15. | [56] | 2023 | China | Quantitative | Males Females | 1209 College Students | 20.17 (Avg) | CB Behaviour | -Higher Incidence of CB -Sense of Security -Gender Differences | -Enhancing Sense of Security -Gender-Specific Interventions -Awareness and Education |

| 16. | [69] | 2024 | United States of America | Quantitative | Males Females Not Identified | 434 Undergraduate Students | 18–24 | Role-Based CB | -Moral Disengagement -Gender Differences -Self-Blame Among Victims -Anonymity and Accessibility -Overlapping Roles | -Reducing Moral Disengagement -Promoting Prosocial Behaviours -Educational Programmes -Self-Efficacy Training |

| 17. | [57] | 2024 | Indonesia | Quantitative | Males Females | 127 Internet Users | 16–27 | Bystander-Influenced CB | -Anonymity of the Bully -Widespread Nature -Detection Difficulty -Bystander Inaction -Gender Differences | -Promoting Personal Peacefulness -Gender-Specific Interventions -Raising Awareness |

| 18. | [78] | 2024 | Australia | Qualitative | N/A | 31 Popular Digital Platforms | N/A | Public Figure CB | -Higher Thresholds for Intervention -Inconsistent Policies -Lack of Clear Definitions -Ethical and Risk Assessment Gaps -Resource Disparities -Withdrawal from Public Life -Quality of Public Discourse | -Equal Protection Policies -Transparent Practices -Rigorous Risk Assessment -Regulatory Pressure -Public Awareness and Education -Ethical Frameworks |

| 19. | [49] | 2024 | Pakistan | Quantitative | Males Females | 1000 Social Media Users | 18–50+ | Personal CB | -Negative Emotions -Public Humiliation -Fear and Intimidation -Difficulty in Detecting Bullying Content -Psychological Impacts | -Regulated Use of Social Media -Social Media Detoxification -Awareness of Online Information Disclosure -Privacy Concerns as a Motivator |

| 20. | [79] | 2023 | Canada | Qualitative | N/A | 20 Participants (Principals, Counsellors, Technology Consultants, Researchers, Police Officers, etc.) | N/A | CB | -Overestimation of Youth Maturity -Lack of Comprehensive Research -Resource and Financial Constraints -Need for Continuous Education | -Educational Efforts -Digital Citizenship Programming -Social Skills Training -Family Involvement -Restorative Conferencing |

| 21. | [71] | 2021 | Australia | Quantitative | Females | 92 University Students | 18–48 | Weight-Based CB | -Influence of Negative Comments -Normative Social Influence -Weight Bias | -Promoting Positive Comments -Developing Better Protocols -Encouraging Body-Positive Content -Educational Programmes -Support Systems |

| 22. | [50] | 2022 | Pakistan | Quantitative | Males Females | 470 Administrative Employees | 19–60 | Workplace CB (WCB) | -Anonymity and Scale -Boundary-Blurring Nature -Cultural Acceptance -Lack of Awareness and Policies -Impact on Psychological Well-Being and Work Engagement | -Awareness and Training -Policy Development -Support Programmes -Collaboration with Legal Authorities -Promoting Psychological Well-Being and Work Meaningfulness |

| 23. | [70] | 2024 | Malaysia | Quantitative | Males Females Prefer Not to Say | 309 Participants | 18–30 | CB Among Adults | -Lack of Awareness and Understanding -Limited Reporting and Help-Seeking -Sociodemographic Influences -Heavy Social Media Use -Family Involvement -Educational Environment | -Targeted Interventions and Policies -Limiting Social Media Usage -Educational Programmes -Family Involvement -Digital Literacy and Cyber Etiquette -Collaboration Among Stakeholders -Use of Digital Interventions |

| 24. | [51] | 2023 | Indonesia | Quantitative | Males Females | 958 Social Media Users | 18–40 | CB in Social Media Scale (CSMS) | N/A | -Screening and Assessment with CSMS -Guiding Interventions -Raising Awareness -Informing Policy |

| 25. | [52] | 2022 | China | Quantitative | Males Females | 928 Internet Users | 16–50 | Perpetrator–Victim CB | N/A | -Enhancing Emotion Regulation -Strengthening Constraints -Promoting Morality -Cross-Sectoral Response -Support for CB Victims -Clear Definitions and Policies -Educational Programmes |

| 26. | [58] | 2021 | Spain | Quantitative | Males Females | 848 Participants | 21–62 | Emotionally Driven CB | N/A | -Emotional Intelligence Training -Attention to Emotional Competencies -Gender- and Age-Specific Interventions -Awareness and Education -Support Systems |

| 27. | [59] | 2022 | China | Quantitative | Males Females | 660 College Students | 17–21 | Comparison-Based CB | N/A | -Reducing Cyber Upward Social Comparison -Enhancing Online Social Support -Education and Awareness -Promoting Positive Online Behaviour -Interventions to Reduce Moral Justification -Strengthening Online Regulations |

| 28. | [60] | 2022 | Spain | Quantitative | Males Females | 1122 Bachelor’s Students | 20.82 (Avg) | Educator Response CB | N/A | -Active Coping Strategies (Such as Seeking Support From Peers, Parents, and Teachers and Calling a Bullying Helpline) -Teacher Training -Reflecting on Personal Factors -Deconstructing Moral Disengagement -Encouraging Positive Traits -Comprehensive Education Programmes -Creating a Supportive Environment |

| 29. | [65] | 2024 | Türkiye | Quantitative | Males Females | 392 University Students | 18–46 | Verbal and Symbolic CB | N/A | -Educational Programmes -Institutional Support Mechanisms -Peer Support Networks -Promoting Courtesy and Respect -Stricter Laws and Policies -Active Bystander Intervention -Awareness Campaigns -Monitoring and Updating Measures |

| 30. | [61] | 2024 | Jordan | Quantitative | Males Females | 872 Academic Staff | 30–50+ | Workplace CB | N/A | -Enhancing Social Capital -Developing Occupational Safety Policies -Promoting Cooperation and Belonging -Raising Awareness and Education -Implementing Support Systems -Encouraging Ethical Leadership |

| 31. | [80] | 2025 | New Zealand | Applied Research | N/A | N/A | N/A | Technological CB Prevention | -Nuanced and Evolving Language -Timely Interventions -Balancing Safety and Privacy -Customization and Flexibility -Scalability and Integration | -Serenity Chat Application -Real-Time Detection and Feedback (Serenity) -Customisable Tolerance Levels -Custom Lexicon -Guardian Monitoring -Nudge Mechanism -Scalability and Integration |

| 32. | [66] | 2023 | USA | Mixed (Qualitative and Quantitative) | Males Females | 25 University Faculty Members | 18+ | Workplace CB | -No Clear CB Policy -Retaliation -Lack Of Trust -Fear -Knowing Nothing Will Be Done -Hassle To Report -Intimidation -Shame -Expectations To Handle Situation -Lack Of Awareness Of Reporting | -Clear CB Policies -Anonymous Reporting System -CB Committees -Mandatory Training -Awareness Campaigns And Workshops -Anti-CB Software to be installed on campus computers and virtual networks |

References

- DataReportal. Number of Internet and Social Media Users Worldwide as of October 2023 (in Billions). 2024. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-october-global-statshot (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Shaikh, F.B.; Rehman, M.; Amin, A. Cyberbullying: A Systematic Literature Review to Identify the Factors Impelling University Students towards Cyberbullying. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 148031–148051. [Google Scholar]

- Ibna Seraj, P.M.; Klimova, B.; Muthmainnah, M. A Systematic Review on the Factors Related to Cyberbullying for Learners’ Wellbeing. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2024, 13, 1877–1899. [Google Scholar]

- McHaney, R. The New Digital Shoreline: How Web 2.0 and Millennials are Revolutionizing Higher Education; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Asanan, Z.Z.B.T.; Hussain, I.A.; Laidey, N.M. A Study on Cyberbullying: Its Forms, Awareness and Moral Reasoning Among Youth; Asia Pacific University: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

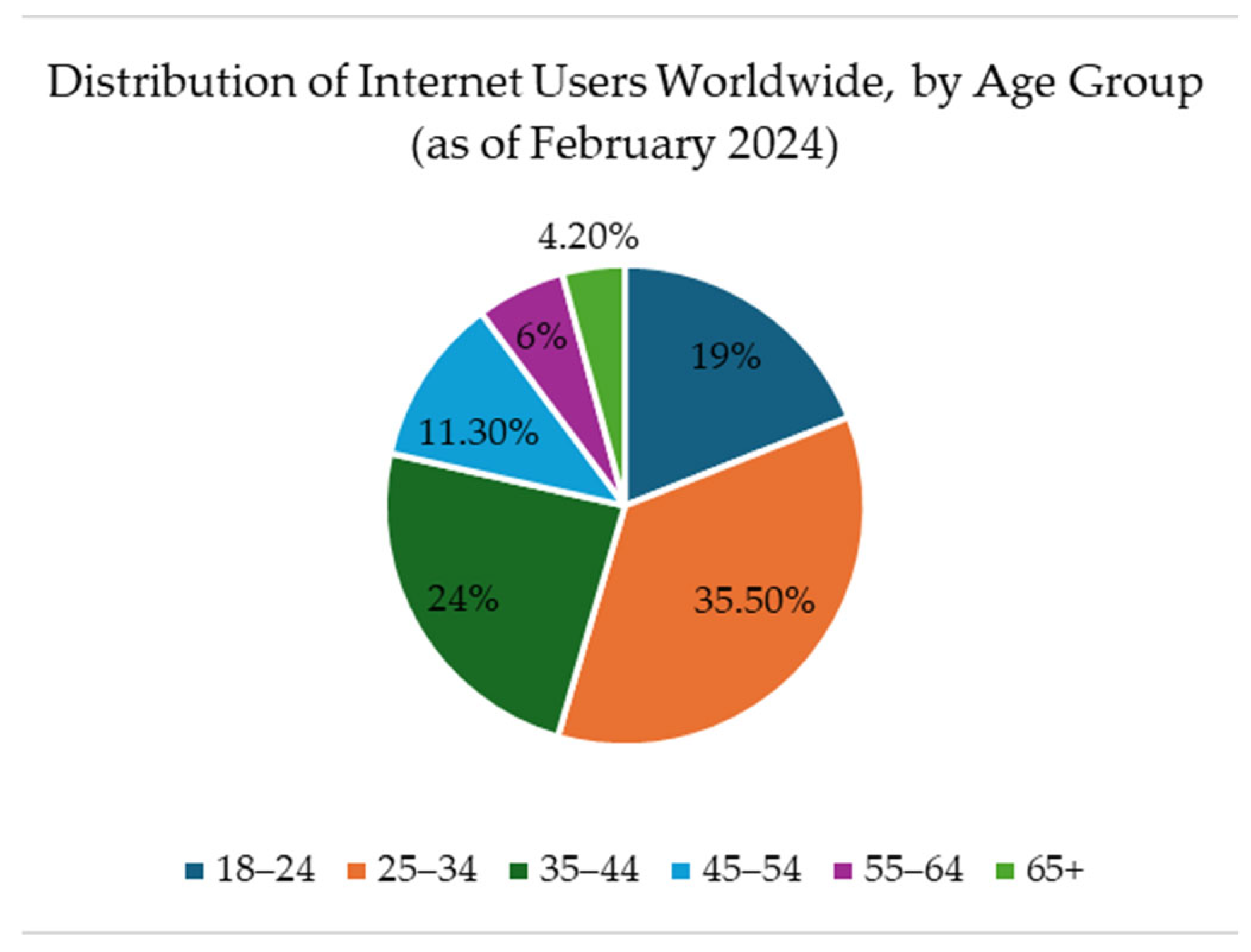

- Petrosyan, A. Age Distribution of Internet Users Worldwide 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272365/age-distribution-of-internet-users-worldwide/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Kowalski, R.M.; Limber, S.P. Electronic bullying among middle school students. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 41, S22–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenaro, C.; Flores, N.; Frías, C.P. Systematic review of empirical studies on cyberbullying in adults: What we know and what we should investigate. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 38, 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Hoareau, N.; Bagès, C.; Allaire, M.; Guerrien, A. The role of psychopathic traits and moral disengagement in cyberbullying among adolescents. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2019, 29, 321–331. [Google Scholar]

- Patchin, J.W.; Hinduja, S. Measuring cyberbullying: Implications for research. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 23, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, V.L. Blocking and self-silencing: Undergraduate students’ cyberbullying victimization and coping strategies. TechTrends 2021, 65, 164–173. [Google Scholar]

- Doumas, D.M.; Midgett, A. Witnessing cyberbullying and internalizing symptoms among middle school students. Eur. J. Investig. Health. Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabito, B.S.; Rodriguez, R.L.; Diloy, M.A.; Trillanes, A.O.; Macato, L.G.T.; Octaviano, M.V. Exploring mobile game addiction, cyberbullying, and its effects on academic performance among tertiary students in one university in the Philippines. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2018-2018 IEEE Region 10 Conference, Jeju, Korea, 28–31 October 2018; pp. 1859–1864. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.L.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.C. How students react to different cyberbullying events: Past experience, judgment, perceived seriousness, helping behavior and the effect of online disinhibition. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 110, 106338. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Shin, N. Prevalence of cyberbullying and predictors of cyberbullying perpetration among Korean adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.K.; Steffgen, G. The COST Action on cyberbullying: Developing an international network. Annu. Rev. Cyberther. Telemed. 2013, 2013, 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, C.-A.; Cowie, H. Cyberbullying across the lifespan of education: Issues and interventions from school to university. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlett, C.P.; Chamberlin, K. Examining cyberbullying across the lifespan. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 444–449. [Google Scholar]

- Kizza, P.J. Unmasking the Cyberbully: Understanding the Psychological and Social Dynamics behind Online Abuse. Res. Invent. J. Law Commun. Lang. 2024, 3, 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Vogels, E.A. The State of Online Harassment. 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/ (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J.W. Digital dating abuse among a national sample of US youth. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 11088–11108. [Google Scholar]

- Pabian, S. An investigation of the effectiveness and determinants of seeking support among adolescent victims of cyberbullying. Soc. Sci. J. 2019, 56, 480–491. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, I.; Gountsidou, V. The role of the industry in reducing cyberbullying. In Cyberbullying Through the New Media; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 2013; pp. 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Force, EC Social Networking Task. Safer Social Networking Principles for the EU; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Guckin, C.; Perren, S.; Corcoran, L.; Cowie, H.; Dehue, F.; Ševčíková, A.; Völlink, T. Coping with Cyberbullying: How Can We Prevent Cyberbullying and How Victims Can Cope with It. 2014. Available online: https://www.tara.tcd.ie/handle/2262/67702 (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Van Royen, K.; Poels, K.; Vandebosch, H.; Adam, P. “Thinking before posting?” Reducing cyber harassment on social networking sites through a reflective message. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 66, 345–352. [Google Scholar]

- Zych, I.; Farrington, D.P.; Ttofi, M.M. Protective factors against bullying and cyberbullying: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019, 45, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, K.; Khan, S.A.; Javeed, A.M.D.; Iqbal, A. Factors influencing cyberbullying among citizens: A systematic review of articles published in refereed journals from 2010 to 2023. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2024. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.; Khan, N.F.; Zafar, S.; Raza, N. Systematic literature reviews in cyberbullying/cyber harassment: A tertiary study. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 102055. [Google Scholar]

- Nocentini, A.; Zambuto, V.; Menesini, E. Anti-bullying programs and Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs): A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 23, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobles, M.R.; Reyns, B.W.; Fox, K.A.; Fisher, B.S. Protection against pursuit: A conceptual and empirical comparison of cyberstalking and stalking victimization among a national sample. Justice Q. 2014, 31, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainudin, N.M.; Zainal, K.H.; Hasbullah, N.A.; Wahab, N.A.; Ramli, S. A review on cyberbullying in Malaysia from digital forensic perspective. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Information and Communication Technology (ICICTM), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 16–17 May 2016; pp. 246–250. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, S.; Metzger-Riftkin, J. Doxxing. In The international encyclopedia of gender, media, and communication; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Austen, A.; Wellington, A.A. Outing: The Supposed Justifications. Can. J. Law Jurisprud. 1995, 8, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlangu, T.; Tu, C.; Owolawi, P. A review of automated detection methods for cyberbullying. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Intelligent and Innovative Computing Applications (ICONIC), Plaine Magnien, Mauritius, 6–7 December 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Alonzo, M.; Aiken, M. Flaming in electronic communication. Decis. Support. Syst. 2004, 36, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maichum, K.; Parichatnon, S.; Peng, K.-C. Application of the extended theory of planned behavior model to investigate purchase intention of green products among Thai consumers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zickuhr, K. Generations 2010. 2010. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2010/12/16/generations-2010/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Patchin, J.W.; Hinduja, S. Bullies move beyond the schoolyard: A preliminary look at cyberbullying. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2006, 4, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Giumetti, G.W.; Schroeder, A.N.; Lattanner, M.R. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.K.; Mahdavi, J.; Carvalho, M.; Fisher, S.; Russell, S.; Tippett, N. Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, N.E. Cyberbullying and Cyberthreats: Responding to the Challenge of Online Social Aggression, Threats, and Distress; Research press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Torraco, R. Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2005, 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B. Procedures for Performing Systematic Reviews; Keele University: Keele, UK, 2004; Volume 33, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zych, I.; Ortega-Ruiz, R.; Marín-López, I. Cyberbullying: A systematic review of research, its prevalence and assessment issues in Spanish studies. Psicol. Educ. 2016, 22, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Hernández, F.; Bonell, L.; Martínez-González, A. A systematic literature review of factors that moderate bystanders’ actions in cyberbullying. Cyberpsychology J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2018, 12, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Brereton, P.; Kitchenham, B.A.; Budgen, D.; Turner, M.; Khalil, M. Lessons from applying the systematic literature review process within the software engineering domain. J. Syst. Softw. 2007, 80, 571–583. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Group, P.-P. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Niu, J.; Mazhar, B.; Haq, I.U.; Maqsood, F. Protecting Privacy on Social Media: Mitigating Cyberbullying and Data Heist Through Regulated Use and Detox, with a Mediating Role of Privacy Safety Motivations. Soc. Media+ Soc. 2024, 10, 20563051241306331. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, A.; Kee, D.M.H.; Ijaz, M.F. Social Media Bullying in the Workplace and Its Impact on Work Engagement: A Case of Psychological Well-Being. Information 2022, 13, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audinia, S.; Maulina, D.; Novrianto, R.; Sudewaji, B.A.; Lotusiana, I.A. The Development of Cyberbullying in Social Media Scale. JP3I (J. Pengukuran Psikol. Dan Pendidik. Indones.) 2023, 12, 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Peng, H. The impact of strain, constraints, and morality on different cyberbullying roles: A partial test of Agnew’s general strain theory. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 980669. [Google Scholar]

- Steinvik, H.R.; Duffy, A.L.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J. Bystanders’ Responses to Witnessing Cyberbullying: The Role of Empathic Distress, Empathic Anger, and Compassion. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2023, 6, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zǎvoianu, E.-A.; Pȃnișoarǎ, I.-O. Cyberbullying prevention and intervention programs-are they enough to reduce the number of the acts of online aggression? J. Educ. Cult. Soc. 2020, 11, 126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, T.; Liao, J.; Deng, Y.; Li, L. Cyberbullying Victimization and Social Anxiety: Mediating Effects with Moderation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, S.; Wang, W.; Xiao, Y. Left-Behind Experiences and Cyberbullying Behavior in Chinese College Students: The Mediation of Sense of Security and the Moderation of Gender. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhri, N.; Firdaus, F.; Buchori, S.; Fakhri, R.A. Personal Peacefulness and Cyber-Bystanding of Internet Users in Indonesia. J. Pendidik. Agama Islam 2024, 21, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra Bustamante, J.; Yuste Tosina, R.; López Ramos, V.M.; Mendo Lázaro, S. The modelling effect of emotional competence on cyberbullying profiles. Anal. Psicol. 2021, 37, 202–209. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, H.; Kong, X.; Feng, Y. The relationship between cyber upward social comparison and cyberbullying behaviors: A moderated mediating model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1017775. [Google Scholar]

- Heras, M.L.; Yubero, S.; Navarro, R.; Larrañaga, E. The Relationship between Personal Variables and Perceived Appropriateness of Coping Strategies against Cybervictimisation among Pre-Service Teachers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawashdeh, M.N.; Alsawalqa, R.O.; Alnajdawi, A.; Aljboor, R.; AlTwahya, F.; Ibrahim, A.M. Workplace cyberbullying and social capital among Jordanian university academic staff: A cross-sectional study. Hum. Soc. Sci. Comm. 2024, 11, 334. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, B. Attachment anxiety and cyberbullying victimization in college students: The mediating role of social media self-disclosure and the moderating role of gender. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1274517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Monteagudo, M.C.; Delgado, B.; García-Fernández, J.M.; Ruíz-Esteban, C. Cyberbullying in the University Setting. Relationship With Emotional Problems and Adaptation to the University. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajbhandari, J.; Rana, K. Cyberbullying on social media: An analysis of teachers’ unheard voices and coping strategies in Nepal. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2023, 5, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Sengül, H. University Students’ Perceptions and Reactions to Cyberbullying on Social Media: The Case of Türkiye. J. Infant Child Adolesc. Psychother. 2024, 23, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarbrough, J.R.W.; Sell, K.; Weiss, A.; Salazar, L.R. Cyberbullying and the faculty victim experience: Perceptions and outcomes. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- António, R.; Guerra, R.; Moleiro, C. Cyberbullying during COVID-19 lockdowns: Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes for youth. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 1067–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasavva, V. I’ll be There for You? The Bystander Intervention Model and Cyber Aggression; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, R.; Gilbertson, M.; Riffle, L.N.; Demaray, M.K. Participant role behavior in cyberbullying: An examination of moral disengagement among college students. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2024, 6, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, W.; Lau, B.T.; Fu, S.T.; Tee, M.K.T.; Islam, F.M.A. Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Cyberbullying Experience and Practice Among Youths in Malaysia. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, D.; Mansfield, H.; Hayes, S.; Smith, E. ‘She Should Not Be a Model’: The Effect of Exposure to Plus-Size Models on Body Dissatisfaction, Mood, and Facebook Commenting Behaviour. Behav. Change 2021, 38, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsawalqa, R.O. Evaluating Female Experiences of Electronic Dating Violence in Jordan: Motivations, Consequences, and Coping Strategies. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 719702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Sun, J.; Li, J.; Lyu, S. Coping strategies, stigmatizing attitude, and cyberbullying among Chinese college students during the COVID-19 lockdown. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 8394–8402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelwall, M.; Cash, S. Bullying discussions in UK female influencers’ YouTube comments. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2021, 49, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faucher, C.; Cassidy, W.; Jackson, M. Awareness, policy, privacy, and more: Post-secondary students voice their solutions to cyberbullying. Eur. J. Investig. Health. Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 795–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bork-Hüffer, T.; Mahlknecht, B.; Kaufmann, K. (Cyber)Bullying in schools–when bullying stretches across cON/FFlating spaces. Child. Geogr. 2021, 19, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Agrawal, S. Perceived vulnerability of cyberbullying on social networking sites: Effects of security measures, addiction and self-disclosure. Indian. Growth Dev. Rev. 2020, 14, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, R.; Henry, N.; Huynh, T.B.; Gleave, J.; Grechyn, V.; Greenfield, S. Platform policy and online abuse: Understanding differential protections for public figures. Convergence 2024, 30, 2152–2167. [Google Scholar]

- Hendry, B.P.; Hellsten, L.-a.M.; McIntyre, L.J.; Smith, B.R. Recommendations for cyberbullying prevention and intervention: A Western Canadian perspective from key stakeholders. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1067484. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, J.; Kishore, S.; Yang, X. A real-time cyberbully checker. Softw. Impacts 2025, 23, 100710. [Google Scholar]

- Aguayo, L.; Hernandez, I.G.; Yasui, M.; Estabrook, R.; Anderson, E.L.; Davis, M.M.; Briggs-Gowan, M.J.; Wakschlag, L.S.; Heard-Garris, N. Cultural socialization in childhood: Analysis of parent–child conversations with a direct observation measure. J. Fam. Psychol. 2021, 35, 138. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, J.; Marchlewska, M.; Molenda, Z.; Górska, P.; Gawęda, Ł. Adherence to safety and self-isolation guidelines, conspiracy and paranoia-like beliefs during COVID-19 pandemic in Poland-associations and moderators. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 294, 113540. [Google Scholar]

- Notar, C.E.; Padgett, S.; Roden, J. Cyberbullying: Resources for Intervention and Prevention. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2013, 1, 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Lizut, J. Cyberbullying victims, perpetrators, and bystanders. In Cyberbullying and the Critical Importance of Educational Resources for Prevention and Intervention; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 144–172. [Google Scholar]

- Polanco-Levicán, K.; Salvo-Garrido, S. Bystander roles in cyberbullying: A mini-review of who, how many, and why. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 676787. [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandric, A.; Pankaj, H.; Wilson, G.M.; Nilizadeh, S. Sadness, Anger, or Anxiety: Twitter Users’ Emotional Responses to Toxicity in Public Conversations. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.11436. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, S.; Raju, V.V. Cyberbullying: A Narrative Review. J. Ment. Health Hum. Behav. 2023, 28, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Turif, G.A.; Al-Sanad, H.A. The repercussions of digital bullying on social media users. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1280757. [Google Scholar]

- El Asam, A.; Samara, M. Cyberbullying and the law: A review of psychological and legal challenges. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 65, 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni, M.; Durve, S.; Jia, B. Cyberbully and Online Harassment: Issues Associated with Digital Wellbeing. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.18989. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, E.D.; Chua, J.Y.X.; Shorey, S. The effectiveness of educational interventions on traditional bullying and cyberbullying among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abus. 2022, 23, 132–151. [Google Scholar]

- Nee, C.N.; Samsudin, N.; Chuan, H.M.; Bin Mohd Ridzuan, M.I.; Boon, O.P.; Binti Mohamad, A.M.; Scheithauer, H. The digital defence against cyberbullying: A systematic review of tech-based approaches. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 2288492. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, S.; Newman, M.L. Testing assumptions about cyberbullying: Perceived distress associated with acts of conventional and cyber bullying. Psychol. Violence 2013, 3, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, M.; Booth, J.M.; Messing, J.T.; Thaller, J. Experiences of online harassment among emerging adults: Emotional reactions and the mediating role of fear. J. Interpers. Violence 2016, 31, 3174–3195. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, W.; Faucher, C.; Jackson, M. The dark side of the ivory tower: Cyberbullying of university faculty and teaching personnel. Alta. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 60, 279–299. [Google Scholar]

- Pepler, D.; Mishna, F.; Doucet, J.; Lameiro, M. Witnesses in cyberbullying: Roles and dilemmas. Child. Sch. 2021, 43, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, M.F. The relationship between young adults’ beliefs about anonymity and subsequent cyber aggression. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 858–862. [Google Scholar]

- Patchin, J.W.; Hinduja, S. Deterring teen bullying: Assessing the impact of perceived punishment from police, schools, and parents. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2018, 16, 190–207. [Google Scholar]

- Elsaesser, C.; Russell, B.; Ohannessian, C.M.; Patton, D. Parenting in a digital age: A review of parents’ role in preventing adolescent cyberbullying. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2017, 35, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, E.; Kowalski, R.M. Cyberbullying via social media. J. Sch. Violence 2015, 14, 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Shah, M.; Foster, M.; Alraja, M.N. Cybercrime Resilience in the Era of Advanced Technologies: Evidence from the Financial Sector of a Developing Country. Computers 2025, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shambira, L. Exploring the adoption of artificial intelligence in the Zimbabwe banking sector. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddeo, M. Three ethical challenges of applications of artificial intelligence in cybersecurity. Minds Mach. 2019, 29, 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Yeoh, P. Artificial intelligence: Accelerator or panacea for financial crime? J. Financ. Crime 2019, 26, 634–646. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Shah, M. What Hinders Adoption of Artificial Intelligence for Cybersecurity in the Banking Sector. Information 2024, 15, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cyberbullying | Source |

|---|---|

| “willful and repeated harm inflicted through the use of computers, cell phones, or other electronic devices”. | [39] |

| “the use of electronic communication technologies to bully others”. | [40] |

| “An aggressive, intentional act carried out by a group or individual, using electronic forms of contact, repeatedly and overtime against a victim who cannot easily defend him or herself”. | [41] |

| “Being cruel to others by sending or posting harmful material or engaging in other forms of social aggression using the Internet or other digital technologies”. | [42] |

| “intentional harmful behaviour carried out by a group or individuals, repeated over time, using modern digital technology to aggress against a victim who is unable to defend herself/himself”. | [43] |

| SLR Steps | SLR Activities |

|---|---|

| Planning Review | Formulating Research Questions |

| Develop Review Protocol | |

| Establishing Data Source | |

| Conducting Review | Identify Appropriate Studies |

| Select Primary Studies | |

| Evaluate Quality of Study | |

| Extract Required Data | |

| Synthesise Data | |

| Documenting Review | Write a Review Report |

| No. | Themes | Forms of CB | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | General and Contextual CB | CB in General CB Behaviour | [56,73,74,77] |

| 2. | Role- and Influence-Based CB | Perpetrator–Victim CB Bystander-Influenced CB Role-Based CB | [52,57,68,69] |

| 3. | Youth, Social Media, and Educational CB | CB among Adults CB in Social Media Scale (CSMS) Educator Response CB | [51,60,70,79] |

| 4. | Workplace and Professional CB | Workplace CB (WCB) | [50,61,64,66] |

| 5. | Psychological and Emotionally Driven CB | Psychological CB Emotionally Driven CB Social Anxiety Comparison-Based CB | [55,58,59,63] |

| 6. | Aggressive, Malicious, and Exploitative CB | Aggressive and Sexual CB Malicious CB Electronic Dating Violence (EDV) Exploitative CB Deceptive CB | [54,62,72,75,76] |

| 7. | Public, Personal, and Character-Based CB | Public Figure CB Public Shaming CB Personal CB Weight-Based CB Verbal and Symbolic CB | [49,53,65,71,78] |

| 8. | Multi-Faceted CB and CB Prevention | Multi-Faceted CB Technological CB Prevention | [67,80] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Batool, I.; Shah, M.; Dhawankar, P.; Gonul, S. Behind the Screens: A Systematic Literature Review on Barriers and Mitigating Strategies for Combating Cyberbullying. Information 2025, 16, 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16040263

Batool I, Shah M, Dhawankar P, Gonul S. Behind the Screens: A Systematic Literature Review on Barriers and Mitigating Strategies for Combating Cyberbullying. Information. 2025; 16(4):263. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16040263

Chicago/Turabian StyleBatool, Irsa, Mahmood Shah, Piyush Dhawankar, and Sinan Gonul. 2025. "Behind the Screens: A Systematic Literature Review on Barriers and Mitigating Strategies for Combating Cyberbullying" Information 16, no. 4: 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16040263

APA StyleBatool, I., Shah, M., Dhawankar, P., & Gonul, S. (2025). Behind the Screens: A Systematic Literature Review on Barriers and Mitigating Strategies for Combating Cyberbullying. Information, 16(4), 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16040263