Abstract

The growing demand for accessible and effective e-learning platforms has led to an increased focus on innovative solutions to address the challenges posed by the diverse linguistic backgrounds of learners. This paper explores the use of AI-generated virtual speakers to enhance multilingual e-learning experiences. This study employs a system developed using Google Sheets and Google Script to create and manage multilingual courses, integrating AI-powered virtual speakers to deliver content in learners’ native languages. The e-learning platform used is a customized Moodle, and three courses were developed: “Mental Wellbeing in Mining”, “Rescue in the Mine”, and “Risk Assessment” for a European ERASMUS+ project. This study involved 147 participants from various educational and professional backgrounds. The main findings indicate that AI-generated virtual speakers significantly improve the accessibility of e-learning content. Participants preferred content in their native language and found AI-generated videos effective and engaging. This study concludes that AI-generated virtual speakers offer a promising approach to overcoming linguistic barriers in e-learning, providing personalized and adaptive learning experiences. Future research should focus on addressing ethical considerations, such as data privacy and algorithmic bias, and expanding the user base to include more languages and proficiency levels.

1. Introduction

The growing demand for accessible and effective e-learning platforms has led to an increased focus on exploring innovative solutions to address the challenges posed by the diverse linguistic backgrounds of learners [1]. Traditionally, the creation of audio and video content for e-learning platforms has been a costly and often ineffective endeavor, as the content may be in a different language than that of the participants [2].

To overcome these limitations, the use of artificial intelligence-generated virtual speakers has emerged as a promising approach. These AI-powered virtual speakers can be programmed to deliver content in the native languages of the learners, thereby enhancing the accessibility and engagement of the learning experience [2]. Furthermore, the integration of AI technologies into e-learning platforms can enable personalized and adaptive learning experiences, tailored to the specific needs and proficiency levels of individual learners [1].

Despite the potential benefits, the implementation of AI-generated virtual speakers in e-learning settings presents several challenges that require careful consideration. The accuracy and naturalness of virtual speech and the seamless integration of AI-powered components into the learning platform are critical factors to address [3]. Additionally, the ethical considerations surrounding the use of AI in education, such as data privacy and algorithmic bias, must be thoroughly examined [3].

Nevertheless, rapid advancements in AI and speech recognition technologies offer significant opportunities for enhancing the language learning experience. By leveraging AI-generated virtual speakers, e-learning platforms can provide learners with a more immersive and personalized learning environment, promoting language acquisition and improving learning outcomes [1,2].

The integration of AI-generated virtual speakers into e-learning platforms holds the promise of overcoming the linguistic barriers that have traditionally hindered the accessibility and effectiveness of online learning.

As technology continues to evolve, opportunities for AI-powered language learning solutions will only grow, paving the way for a more inclusive and engaging e-learning landscape [4].

The ERASMUS+ project named DigiRescueMe, Standardization and Digitalization of Rescue Education in Mining (2021-1-TR01-KA220-VET-000028090), has the goal of developing e-learning modules aimed at increasing the knowledge, mental, and awareness levels of miners, rescue members, and mining engineers on topics related to rescue, risk assessment, and wellbeing, as identified through an investigation of their learning needs [5]. The main goal of the project is to provide easy-to-understand learning content to people from Türkiye, Poland, Portugal, and Italy. Usually, people working in mines do not speak English proficiently and the vocabulary in their own tongue is not so rich in technical terms. For these reasons, a multilanguage approach should be preferred to better engage people and keep content more effective for them. Achieving this by engaging teachers or human speakers of different languages may be expensive and difficult to manage.

2. Related Work

Conventional e-learning approaches have been widely adopted in various educational contexts, offering flexibility and accessibility to learners. Traditional e-learning methods often involve the use of Learning Management Systems (LMSs), such as Moodle, which provide a platform for delivering course content, assessments, and interactive activities. These systems support asynchronous learning, allowing students to access materials at their own pace and convenience. Research has shown that e-learning can be as effective as traditional face-to-face instruction when designed and implemented properly [6]. However, challenges such as learner isolation, lack of engagement, and the need for self-discipline have been noted [7].

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in e-learning has opened new avenues for personalized and adaptive learning experiences. AI-based learning approaches leverage machine learning algorithms, natural language processing, and data analytics to tailor educational content to individual learners’ needs and preferences. These approaches include intelligent tutoring systems, adaptive learning platforms, and AI-driven assessment tools. Studies have demonstrated that AI can enhance learning outcomes by providing real-time feedback, personalized recommendations, and adaptive learning paths [8]. AI-based systems can also analyze large datasets to identify patterns and trends, enabling educators to make data-informed decisions and improve instructional strategies [9].

AI-generated videos and virtual speakers represent a cutting-edge development in e-learning, offering scalable and cost-effective solutions for content delivery. These technologies use advanced machine learning models to create lifelike avatars that can deliver instructional content in multiple languages, enhancing accessibility and engagement. AI video generation platforms, such as ELAI (https://www.elai.io (accessed on 11 December 2024)), HeyGen (https://www.heygen.com (accessed on 11 December 2024)), and Colossyan (https://www.colossyan.com (accessed on 11 December 2024)), allow educators to produce high-quality videos from simple text inputs, significantly reducing production time and costs. Research has shown that AI-generated videos can improve learner engagement and retention by providing consistent, personalized, and visually appealing content [10]. Additionally, virtual speakers can bring a personal touch to e-learning, making complex subjects more approachable and relatable for learners.

3. Materials and Methods

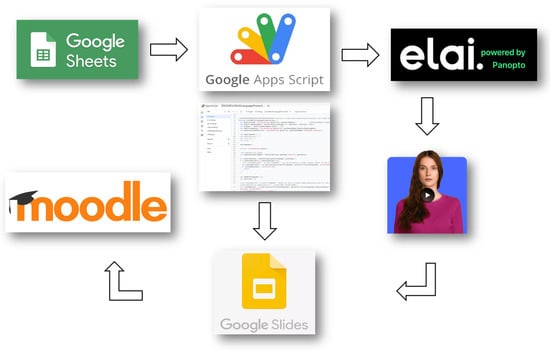

3.1. The Developed System to Manage Content

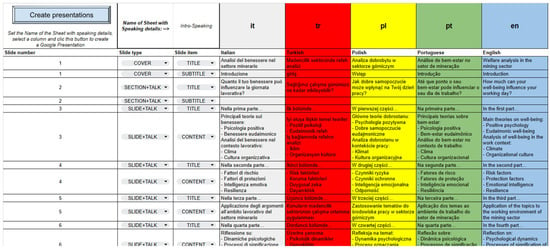

By using Google Sheets and their Google Script programming language, a sort of management system was developed. It supports creating and managing the production of multilanguage courses. It was designed to allow instructional designers to define in their own language what they would like to show in their slides to the learners. By using Google Translator functions directly accessed in the cells of Google Sheets, these details are automatically translated in all the languages they need (Figure 1). This system, using Google Script procedures and a set of slide templates where titles, subtitles, content, and a speaker shape are defined (Figure 2), automatically creates Google Presentations with the detailed slides. It can create one Google presentation for each chosen language.

Figure 1.

Google Sheet to create multilanguage presentations. Each translation has its own color.

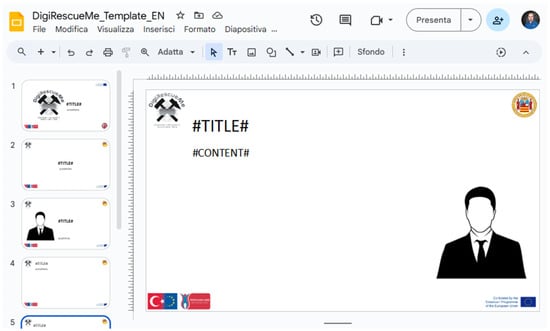

Figure 2.

Google Presentation template with all different types of slides to be used.

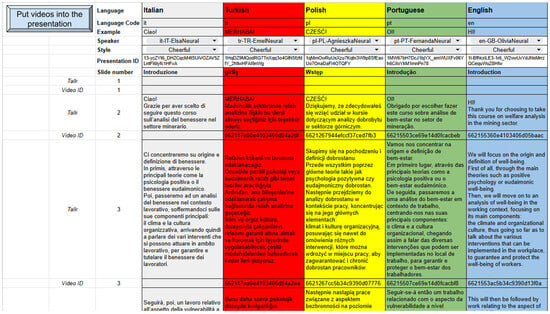

Afterwards, the course designers may define what a teacher should say on each slide by writing their speeches and, still using Google Translator functions, translating them into the languages they want (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Google Sheet to create multilanguage videos with virtual speaking avatars.

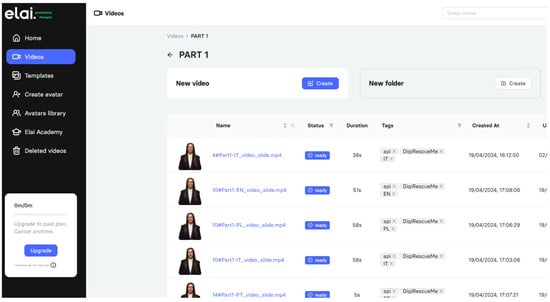

By using the API, an external artificial intelligence engine may be called to create virtual talking avatars. For this project, ELAI was selected since it offers high quality in generating speaking avatars (Figure 4), and many API functions were called directly from Google scripts. It allowed automating the process of creating multilanguage content. The talking avatar videos can be created, downloaded, and integrated into Google slides directly by using Google Script procedures. The schema of the logic implemented is shown in Figure 5. Specifically, the Google script procedures may be called by clicking on the buttons in the sheets. These procedures create new Google slides by customizing the templates and substituting titles and texts in all the selected languages. Figure 6 shows the translations of the same slide in English (a), Italian (b), Turkish (c), and Polish (d). After that, they can call the ELAI engine through its API to generate videos with talking avatars using the text written as speech. Finally, these videos are added into the Google presentations, and the presentations themselves are uploaded as resources onto the Moodle platform.

Figure 4.

The ELAI environment to create virtual speaking avatars.

Figure 5.

The architecture and the logic of the management system.

Figure 6.

Multilanguage slides automatically created by the developed Google Script procedures in (a) English; (b) Italian; (c) Turkish; and (d) Polish.

3.2. The E-Learning Platform

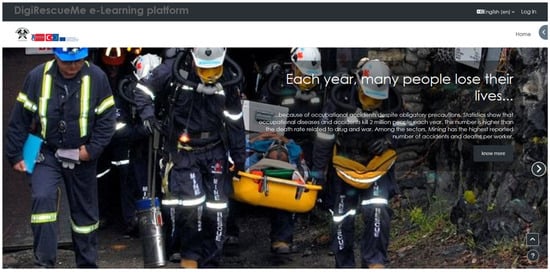

The e-learning platform used is a Moodle 4.3 customized to meet the needs of the project.

The Moodle platform used for the purposes of the project possessed many features. In particular, its high graphic customization allowed us to follow the display specifications adopted for the project. The multilingual display plug-in allowed us to upload titles, texts, and messages in all languages of the project and to display them according to the user’s preferences (Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the pages in English). The page authoring features allowed us to create containers within which to directly upload presentations in Google Slides format. The quiz authoring features allowed us to create all the evaluation tests to be inserted in the courses. The functionality for the creation of questionnaires allowed us to create the final evaluation questionnaire and to export the data collected for the analyses presented here.

Figure 7.

The home page of the e-learning platform.

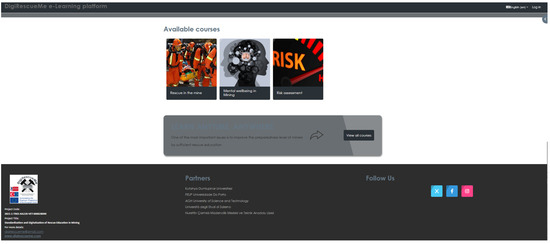

Figure 8.

The course catalog.

3.3. The Courses

Three courses were created:

- “Mental wellbeing in Mining”, which covers

- Basic information on mental wellbeing.

- Risks of work-related stress.

- Stress reactions.

- Stress factors.

- Sentinel events.

- “Rescue in the mine”, which covers

- General definitions of mining rescue.

- Formal legal aspects of rescuing.

- Structure of rescue response units.

- Types and organization of rescue activities in mining.

- Rescue equipment.

- Natural and technical hazards in mining and their prevention.

- “Risk assessment”, which covers

- Risk analysis terms (hazard, risk, near miss, work accident, etc.).

- Hazard identification processes.

- Examples of hazards in mines.

- Risk management stages and mining applications.

- Risk analysis methods.

- Matrix Method.

- Fine–Kinney Method.

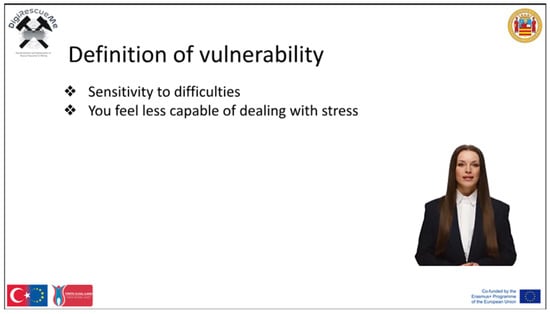

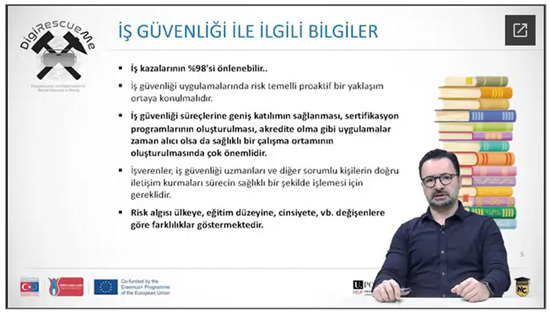

The courses cover topics that, while specific in some cases, are introduced with a gradual approach that makes them particularly accessible and do not require particular prerequisites or prior knowledge to follow. The three courses have the same structure: a mandatory initial assessment with twenty multiple choice questions on the knowledge covered in the course; a sequence of videos with a speaker, supported by slides; a mandatory final assessment with a different set of twenty corresponding multiple choice questions on the covered concepts and a questionnaire to collect their opinions on this e-learning experience. The “Mental wellbeing in Mining” and “Rescue in the mine” courses had a virtual speaker (as shown by Figure 9); the “Risk assessment” course had a human speaker (as shown by Figure 10). Each course had an average duration of about 3 h. No functionality to allow interaction between participants was enabled.

Figure 9.

One of the videos in English with an AI-generated talking avatar.

Figure 10.

One of the videos in Turkish with a human speaker.

3.4. The Questionnaire

Krosnick and Presser [11] emphasized the importance of clear and concise question wording to avoid ambiguity and ensure respondents understand the questions as intended. They recommend using simple language and avoiding technical jargon. They also suggest using a mix of close- and open-ended questions to capture both quantitative and qualitative data. To collect opinions of users on their e-learning experience, a questionnaire was defined inspired by the UEQ model [12], and the TUXEL technique was used for user experience evaluation in e-learning [13].

These references provided insights into the methodologies and findings related to user experience and satisfaction with e-learning platforms to design a questionnaire to be delivered at the end of each course. Table 1 shows the eighteen questions.

Table 1.

The questionnaire.

Many questions allowed the participants to express their opinions on a 4-level scale (Yes, More Yes than No, More No than Yes, No). The two final questions allowed participants to detail what they liked most and what they liked least about the e-learning platform and its content in an open text box.

3.5. The People

During the piloting phase of the project, people from schools, universities, and enterprises from Türkiye, Poland, Portugal, and Italy were asked to take part in our experiments. Each one of them had the opportunity to choose just one of the available courses.

The piloting phase of the project included in-person meetings in which both the e-learning platform and the courses created were presented, and participation was requested from all participants. These presentations took place in school contexts, during conferences and events organized specifically at companies in the mining sector or in conjunction with project meetings held in the various countries involved. The courses were then used asynchronously and autonomously from the beginning of November 2024, till 27 December 2024.

4. Results

4.1. The Participants

One hundred and forty-seven participants provided answers to the questionnaire. Details regarding the number of participants by course, gender, occupation, country, and device used are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Details about the participants.

In the two courses “Mental wellbeing in Mining” and “Rescue in the mine”, AI-generated virtual speakers were used as instructors, while in the course “Risk assessment”, a human teacher was involved. This allowed us to have an experimental group (EG) with 80 participants and a control group (CG) with 67 participants to compare their perception of the content and their e-learning experience.

4.2. The Collected Data

Table 3 shows the data collected by the questionnaire. In particular, it shows the results of question n.5 about the users’ perception of the e-learning platform, of question n.6 about the users’ perception of the topics covered, of question n.9 about the users’ perception of the multilanguage content, of question n.10 about the users’ perception of the AI-generated content, of question n.11 about the users’ perception of the effectiveness of the AI-generated content, of question n.12 about the users’ perception of the non-human speaker; of question n.14 about the possibility of the users returning to view other new content, and of question n.15 about the possibility of the users recommending these courses to their friends.

Table 3.

The results related to questions n.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, and 13.

The collected answers from the question n.15 “What did you like most about the course?” are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

The results related to question n.15 grouped into five different categories.

The collected answers from the question n.16 “What did you like least about the course?” are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

The results related to question n.16 grouped into five different categories.

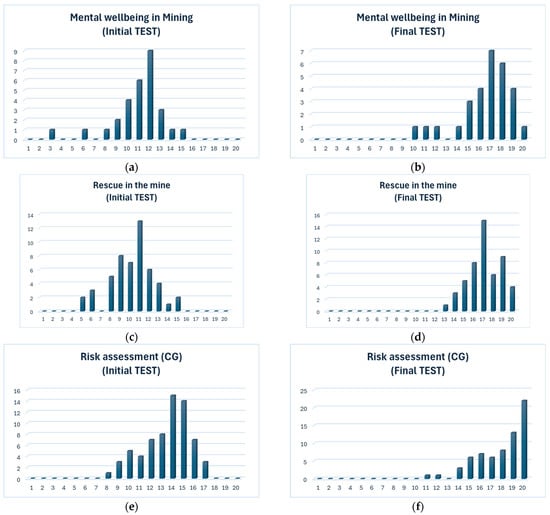

4.3. Initial and Final Assessment Results

As mentioned, the three courses were subjected to an initial assessment and a final assessment, both of which were mandatory. The e-learning platform tracked the results of the users involved.

In all the courses, as shown in Figure 11, it is possible to observe progress in terms of knowledge on the topics covered since, for all the participants, it is possible to see an improvement in the score achieved.

Figure 11.

Results on initial and final assessments on the three courses. (a) Initial assessment results on “Mental wellbeing in Mining”; (b) final assessment results on “Mental wellbeing in Mining”; (c) initial assessment results on “Rescue in the mine”; (d) final assessment results on “Rescue in the mine”; (e) initial assessment results on “Risk assessment”; (f) final assessment results on “Risk assessment”.

5. Discussion

The primary goal of this project was to develop e-learning modules aimed at increasing the knowledge, mental, and awareness levels of miners, rescue members, and mining engineers on topics related to rescue, risk assessment, and wellbeing. Based on the results shown in Figure 11, it appears that all three courses had a positive impact. Participants had a certain level of understanding before the course, and there was a noticeable improvement in their scores, indicating that the courses effectively enhanced their knowledge of mental wellbeing in mining, rescue operations in the mine, and risk assessment. Overall, the courses seem to be well designed and effective in enhancing the participants’ knowledge in their respective areas [14].

However, the majority of participants who responded to the questionnaire were school students (59 out of 147 participants) and university students (35 out of 147 participants), rather than the intended target audience of miners, rescue members, and mining engineers.

This discrepancy can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, the piloting phase of the project aimed to gather initial feedback on the usability and accessibility of the e-learning modules. Students were readily available and willing to participate, providing valuable insights into the general user experience and the effectiveness of the AI-generated content. Their feedback helped identify potential issues and areas for improvement in the e-learning platform, which can be addressed before deploying the modules to the target audience.

Secondly, involving students allowed the researchers to test the scalability and adaptability of the e-learning modules across different age groups and educational backgrounds. This approach ensured that the content was accessible and engaging for a broader audience, which is crucial for the success of any e-learning platform.

However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this approach. Students may lack the specific experience and expertise required to assess the technical content related to mining, rescue, and risk assessment accurately. Their feedback may not fully capture the unique needs and challenges faced by professionals in these fields.

Additionally, 53 more participants responded to the questionnaire. These participants included researchers, specialized technicians, employees, teachers, and unemployed individuals. While their feedback provided diverse perspectives on the e-learning experience, it is essential to recognize that their expertise as miners, rescue members, and mining engineers may provide a more accurate assessment of the overall learning process with respect to their specific needs. However, the main goal of this study was to evaluate participants’ impressions of the AI-generated virtual speaker rather than focusing on the topics or content itself. Future studies should prioritize involving miners, rescue members, mining engineers, and other relevant professionals to obtain more focused and reliable assessments of the e-learning modules.

From the data reported in Table 2 on question n.5, participants from both the EG and CG groups appreciated the quality of the e-learning platform. In EG, 71 participants (89%) answered Yes, and 6 participants (8%) answered More Yes than No. Just one participant (1%) answered More No than Yes and, finally, only two participants (3%) answered No, declaring they did not like it. In CG, 54 participants (81%) answered Yes, and 7 participants (10%) answered More Yes than No. Six participants (9%) answered More No than Yes and, finally, none of the participants answered No.

These responses confirmed that the platform, developed using the Moodle framework with customizations tailored for the project, was appreciated by participants from both the EG and CG groups.

From the data reported in Table 3 on question n.6, participants from both the EG and CG groups appreciated the topics covered in the online courses. In EG, 68 participants (85%) answered Yes, and 6 participants (8%) answered More Yes than No. Just one participant (2%) answered More No than Yes and, finally, five participants (6%) answered No, declaring they were not interested in it. In CG, 54 participants (81%) answered Yes, and 7 participants (10%) answered More Yes than No. Six participants (9%) answered More No than Yes and, finally, none of the participants answered No.

These answers confirmed that participants from both the EG and CG groups found the topics covered in the online courses interesting. Since different courses were delivered to the EG and CG groups, it could be a confounding variable. To minimize the influence of course topics on users’ evaluations of the approaches adopted in the online courses, this question and its related answers should focus solely on the methods used.

The data reported in Table 3 on question n.7 show that the users preferred to view the content in their own language. In EG, 68 participants (85%) answered Yes, and 7 participants (9%) answered More Yes than No. Three participants (4%) answered More No than Yes and, finally, two participants (3%) answered No. In CG, 50 participants (75%) answered Yes, and 12 participants (18%) answered More Yes than No. Three participants (4%) answered More No than Yes, and, finally, two participants (3%) answered No.

These answers confirmed that participants from both the EG and CG groups preferred to view and listen to content in their own language. This will eventually be customized automatically based on the language they select upon logging in.

The data reported in Table 3 on question n.8 show that the users enjoyed the content generated using AI. In EG, 61 participants (76%) answered Yes, and 12 participants (15%) answered More Yes than No. Three participants (4%) answered More No than Yes and, finally, four participants (5%) answered No. In CG, 59 participants (88%) answered Yes, and 5 participants (7%) answered More Yes than No. Just one participant (1%) answered More No than Yes and, finally, two participants (3%) answered No.

These responses confirmed that participants from both the EG and CG groups liked the content (95% expressed a positive perception, including both Yes and More Yes than No responses). A higher percentage of participants preferred the human teacher used in CG compared to the AI-generated teacher used in EG (88% of Yes vs. 76%).

The data reported in Table 3 on question n.9 show that the users felt this communication was effective. In EG, 66 participants (83%) answered Yes, and 7 participants (9%) answered More Yes than No. Four participants (5%) answered More No than Yes and, finally, three participants (4%) answered No. In CG, 49 participants (73%) answered Yes, and 15 participants (22%) answered More Yes than No. Two participants (3%) answered More No than Yes and, finally, one participant (1%) answered No.

These answers confirmed that participants from EG (83%) felt that AI-generated communication was more effective, compared to participants from CG (73%), who had a human teacher instead of a speaker generated by the AI engine.

The data reported in Table 3 on question n.10 show how users perceived an AI-generated speaker in their own language compared to a human speaking in a different language with subtitles. In EG, 14 participants (18%) answered Yes, and 5 participants (6%) answered More Yes than No. A total of 10 participants (13%) answered More No than Yes and, finally, 51 participants (64%) answered No. In CG, one participant (1%) answered Yes, and five participants (7%) answered More Yes than No. A total of 6 participants (9%) answered More No than Yes and, finally, 55 participants (82%) answered No.

These answers confirmed that participants from both the EG and CG groups perceived content in their own language to be considerably more effective than content presented in a different language with subtitles. Of course, people who listened to the human teacher perceived this communication as highly effective and stated that they would not have preferred another speaker with subtitles.

The data reported in Table 3 on question n.12 show whether users would return to the platform to view additional content when it becomes available. In EG, 56 participants (70%) answered Yes, and 13 participants (16%) answered More Yes than No. Four participants (5%) answered More No than Yes and, finally, seven participants (9%) answered No. In CG, 55 participants (82%) answered Yes, and 3 participants (4%) answered More Yes than No. Five participants (7%) answered More No than Yes and, finally, four participants (6%) answered No. These answers confirmed that participants from both the EG and CG groups enjoyed the course they attended, and that they would return for future online experiences on this platform.

The data reported in Table 3 on question n.13 show whether users would recommend the course they attended to colleagues and friends. In EG, 58 participants (73%) answered Yes, and 15 participants (19%) answered More Yes than No. Four participants (5%) answered More No than Yes and, finally, three participants (4%) answered No. In CG, 55 participants (82%) answered Yes, and 5 participants (7%) answered More Yes than No. Four participants (6%) answered More No than Yes and, finally, three participants (4%) answered No. These answers confirmed that participants from both the EG and CG groups enjoyed the course they attended and would recommend it to their friends and colleagues.

As shown in Table 4, responses to the open-ended question n.15 “What did you like most about the course?” revealed that participants most appreciated the assessments, the use of clear and easy-to-understand language in the explanations, and the brevity of videos, which were simple and direct.

As shown in Table 5, responses to the open-ended question n.16 “What did you like least about the course?” revealed that participants disliked the navigation process for the content. Some also felt that the time allocated for the tests or explanations was too short.

The findings of this study reveal a nuanced preference among participants for AI-generated content in e-learning environments, particularly due to its accessibility features. Participants appreciated the AI-generated content for its ability to provide consistent, multilingual, and easily accessible learning materials. This aligns with previous research indicating that AI can significantly enhance accessibility by offering automated image descriptions, real-time text-to-speech conversion, and automated captioning and transcription [1,15]. These features are particularly beneficial for learners with disabilities, language barriers, or different learning styles, making e-learning more inclusive and effective.

However, despite these advantages, participants still showed a preference for human speakers in certain contexts. This preference can be attributed to the unique qualities that human speakers bring to the learning experience, such as emotional engagement, natural speech patterns, and the ability to adapt to the audience’s reactions in real time [16,17]. Human speakers can convey empathy, humor, and other emotional cues that enhance the learning experience, which AI-generated content currently struggles to replicate [17].

These findings are consistent with broader trends in e-learning, where the integration of AI is seen as a tool to complement rather than replace human instructors [18,19,20]. These tools provide instant support, answer questions, and offer explanations, enhancing the overall learning experience [9]. AI systems analyze large datasets to provide insights into learners’ behavior, performance, and engagement. These insights help educators to identify areas where learners may need additional support and to make data-informed decisions about content delivery and instructional strategies [21].

In terms of limitations, it is important to acknowledge that AI-generated content is not without its challenges. Although AI-driven e-learning platforms make learning more interactive and enjoyable [22], issues such as data quality, algorithmic bias, and the potential for over-reliance on AI tools can hinder the learning process [19,23]. Additionally, the lack of emotional and contextual understanding in AI-generated content can make it less engaging and relatable for learners [24]. These initiatives demonstrate the transformative potential of AI in e-learning, offering personalized, efficient, and engaging educational experiences, but there is a need to gather information on pedagogical effects and student perceptions, and expand the user base to include more languages and proficiency levels [25]. AI is transforming education, particularly in language learning and assessment. Educators, institutions, and policymakers must collaborate to fully harness AI’s potential in education. As AI continues to evolve, its capacity to revolutionize education remains promising, requiring ongoing exploration and adaptation. This highlights the transformative potential of AI in education and the importance of addressing challenges to fully realize its benefits [26].

6. Conclusions

This study highlights the potential of AI-generated virtual speakers to enhance multilingual e-learning experiences. The findings indicate that participants appreciated the accessibility and consistency provided by AI-generated content, particularly for learners with diverse linguistic backgrounds. However, the preference for human speakers in certain contexts underscores the importance of emotional engagement and adaptability in the learning process.

The integration of AI technologies into e-learning platforms offers significant opportunities for creating personalized and adaptive learning experiences. By leveraging AI-generated virtual speakers, e-learning platforms can provide more inclusive and engaging learning environments, promoting language acquisition and improving learning outcomes.

Despite these advantages, it is crucial to address the limitations of AI-generated content, such as data quality, algorithmic bias, and the lack of emotional and contextual understanding. Future work could involve offering participants different versions of the same courses to compare their perceptions of the type of speaker, without any possible influence from the topics. Moreover, future research could focus on improving the quality and contextual relevance of AI-generated content and exploring ways to better integrate AI with human instruction.

In conclusion, the combination of AI-generated content and human instruction can create a more balanced and effective e-learning environment. As AI technologies continue to evolve, their potential to revolutionize education remains promising, requiring ongoing exploration and adaptation.

The experiment described in this paper provided preliminary evidence that AI-based technologies could be helpful and offer great support to instructional designers in their arduous work of preparing effective and engaging e-learning experiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and R.V.; methodology, S.M. and R.V.; formal analysis, S.M.; investigation, R.V.; supervision, S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted under the project 2021-1-TR01-KA220-VET-000028090 named DigiRescueMe, Standardization and Digitalization of Rescue Education in Mining, funded by the ERASMUS+ program of the European Union.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Social and Human Sciences Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee of Kütahya Dumlupinar University (protocol code 147851 and date of approval: 17 October 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All information related to the cited project may be found at http://digirescueme.com/ (accessed on 11 December 2024).

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted as part of the needs analysis in the work package O1—Development of Standardized Rescue Curriculum—of the project 2021-1-TR01-KA220-VET-000028090 named DigiRescueMe, Standardization and Digitalization of Rescue Education in Mining, funded by the ERASMUS+ program of the European Union. Special thanks are extended to Oktay ŞAHBAZ and all colleagues from the partner institutions for their engagement in piloting phases, administering the questionnaires, conducting interviews, and many fruitful discussions: Kütahya Dumlupinar Universitesi, Türkiye (DPU); Akademia Gorniczo-Hutnicza Im. Stanislawa Staszica W Krakowie, Poland (AGH); Universidade Do Porto, Portugal (Uporto); and Nurettin Çarmıklı Madencilik Mesleki ve Teknik Anadolu Lisesi, Türkiye (BalVET).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jia, F.; Sun, D.; Ma, Q.; Looi, C.-K. Developing an AI-Based Learning System for L2 Learners’ Authentic and Ubiquitous Learning in English Language. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Y. Exploring the Application of Artificial Intelligence in Foreign Language Teaching: Challenges and Future Development. SHS Web Conf. 2023, 168, 03025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lai, P.; Chan, A.; Man, V.; Chan, C.-H. AI-Assisted Enhancement of Student Presentation Skills: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Lund, B.D.; Marengo, A.; Pagano, A.; Mannuru, N.R.; Teel, Z.A.; Pange, J. Exploring the Potential Impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on International Students in Higher Education: Generative AI, Chatbots, Analytics, and International Student Success. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, S.; Marzano, A.; Vegliante, R. An Investigation of Learning Needs in the Mining Industry. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frăsineanu, E.S.; Ilie, V. Traditional Learning Versus E-Learning. In Education Facing Contemporary World Issues; European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences; Future Academy: Bankstown, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauermeister, T.; Janßen, N.; Engler, J.-O. Conventional teaching vs. e-learning: A case study of German undergraduate biology students. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.H. Machine learning: Algorithms, real-world applications and research directions. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaouni, M.; Lakrami, F.; Labouidya, O. Integrating Artificial Intelligence and Natural Language Processing in E-Learning Platforms: A Review of Opportunities and Limitations. In Proceedings of the 7th IEEE Congress on Information Science and Technology, Agadir-Essaouira, Morocco, 16–22 December 2023; pp. 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D. The impact of AI-enhanced natural language processing tools on writing proficiency: An analysis of language precision, content summarization, and creative writing facilitation. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krosnick, J.A.; Presser, S. Question and questionnaire design. In Handbook of Survey Research, 2nd ed.; Marsden, P.V., Wright, J.D., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2010; pp. 263–313. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, A.M.; Abuaddous, H.Y.; Alansari, I.S.; Enaizan, O. The evaluation of user experience of learning management systems using UEQ. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2022, 7, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, W. TUXEL: A technique for user experience evaluation in e-learning. J. Educ. Psychol. Stud. 2018, 10, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Heil, J.; Ifenthaler, D. Online assessment in higher education: A systematic review. Online Learn. 2023, 27, 187–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adigun, T.A.; Igboechesi, G.P. Exploring the Role of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Enhancing Information Retrieval and Knowledge Discovery in Academic Libraries. Int. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. Stud. 2024, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiker, D.; Ricker Gyllen, A.; Eldesouky, I.; Cukurova, M. Generative AI for learning: Investigating the potential of synthetic learning videos. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Artificial Intelligence in Education, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dinçer, N. The voice effect in multimedia instruction revisited: Does it still exist? J. Pedagog. Res. 2022, 6, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, R.; Sato, H. Evaluation of avatar and voice transform in programming e-learning lectures. J. Multimodal User Interfaces 2020, 15, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.H.; Chauhan, D.; Iqbal, R.A.; Yeoh, E. Mapping academic perspectives on AI in education: Trends, challenges, and sentiments in educational research (2018–2024). Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2024, 09, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, S. Automated content creation for e-learning using AI technologies. Comput. Educ. 2021, 160, 104034. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Data-driven insights in e-learning: Leveraging AI for improved outcomes. J. Learn. Anal. 2020, 7, 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.; Smith, T. Gamification in e-learning: Increasing engagement through AI. J. Interact. Learn. Res. 2021, 32, 567–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, F.; Zheng, L.; Jiao, P. Artificial intelligence in online higher education: A systematic review of empirical research from 2011 to 2020. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 7893–7925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, Y. Embracing the future of Artificial Intelligence in the classroom: The relevance of AI literacy, prompt engineering, and critical thinking in modern education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024, 21, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.H.; Choi, H. Systematic Review for AI-based Language Learning Tools. J. Digit. Contents Soc. 2021, 22, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashmi, D. Unlocking the Potential of AI in Education: Challenges and Opportunities; IJFMR: Vadodara, Gujarat, 2023; Volume 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).