Abstract

High-impedance fault (HIF) feeder detection in resonant-grounded active distribution systems remains a challenging issue. In practice, fault currents are typically weak, and the integration of distributed generation (DG) often distorts fault signatures, significantly limiting the effectiveness of existing detection techniques. This paper presents a novel HIF feeder detection method based on the fusion of zero-sequence current (ZSC) cross-correlation polarity analysis and harmonic wavebody similarity matching. Firstly, the HIF mechanism is examined, and the impact of DG on ZSC behavior is characterized, revealing polarity differences among feeders. To suppress high-frequency interference, variational mode decomposition (VMD) is employed to extract low-frequency components indicative of ZSC polarity, which are then subjected to cross-correlation analysis and used as the primary detection indicator. When ZSCs are heavily distorted due to DG, harmonic wavebody similarity serves as a supplementary detection feature. A comprehensive detection criterion is subsequently formulated by combining both analyses. Simulation and experimental results demonstrate that under HIF conditions, the proposed method is robust against variations in fault location, fault type, and noise interference, and can accurately identify the faulty feeder. Moreover, it remains effective for arc grounding, grass grounding, and pond grounding scenarios, highlighting its strong practical applicability.

1. Introduction

Feeder fault detection in medium-voltage distribution networks remains an unresolved challenge, particularly in resonant-grounded active distribution systems [1]. In the case of single-phase-to-ground faults, the current flowing through the faulty feeder may sometimes be lower than that in healthy feeders. Furthermore, when the grounding resistance is excessively high, the fault signature becomes extremely weak, making it difficult for conventional protection schemes to distinguish the occurrence of a high-impedance fault (HIF). As a result, HIF detection has emerged as both a technical challenge and a research hotspot in recent years [2]. According to studies in the domestic and international literature, existing HIF feeder detection methods can broadly be classified into two categories: macroscopic waveform measurement methods in the time domain and conventional microscopic feature extraction methods.

Macroscopic waveform measurement approaches include grey relational analysis [3], correlation analysis [4], spatial relative distance metrics [5], cosine similarity measures [6,7], and dynamic trajectory tracking methods [8,9]. These techniques primarily analyze zero-sequence current (ZSC) characteristics of feeders in the time domain. However, as they fail to differentiate between transient and steady-state components, their detection accuracy often depends heavily on the chosen data window length. Moreover, these methods are largely limited to time-domain analysis, tending to overlook frequency-dependent features that may be critical for accurate detection. Their performance also deteriorates significantly under extreme fault conditions such as strong noise, missing data, or HIF, making it difficult to establish robust and generalizable detection criteria.

Microscopic feature extraction methods aim to detect fault signatures through advanced signal processing techniques. These include various wavelet-based approaches—such as discrete and continuous wavelet transforms [10,11], wavelet packet decomposition [12], and empirical wavelet transform [13]—as well as mode decomposition methods [14,15], mathematical morphology [16], waveform distortion metrics [17], and time–frequency analysis techniques [18]. Detection rules in this category are typically constructed based on characteristic frequency bands. Compared with macroscopic methods, microscopic feature extraction allows for deeper mining of fault-related patterns in the time, frequency, and time–frequency domains, thereby improving detection accuracy to a certain extent. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of these methods often depends on complex feature extraction procedures and expert knowledge. For instance, in wavelet-based methods [19], the choice of basis functions and decomposition levels directly impacts the quality of feature extraction and, consequently, the accuracy of the detection criterion. The advantages and disadvantages of different methods are summarized in Table 1. In addition, due to the high sampling frequencies required, most of these traditional approaches have not yet seen widespread application in practical engineering. For cases such as ground faults caused by wildfires [20], or scenarios requiring rapid tripping, the inherent complexity of feature extraction and decision-making logic prevents these methods from meeting the fast-acting response requirements of modern protection devices. Therefore, a key practical challenge lies in developing a fault feeder detection method that balances simplicity in implementation with accuracy in results, and that remains effective under adverse operating conditions such as strong noise and HIF.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of different methods.

In addition, in a distribution network with distributed generation (DG), the DG units are often neglected in the zero-sequence network after a single line-to-ground (SLG) fault, since they are usually connected to the grid through Δ/Y transformers, and the ZSC does not flow through the transformer. However, the zero-sequence network is actually connected in series with the three sequence networks at the fault point. Therefore, when an SLG fault occurs on a feeder with a connected DG unit, the DG will influence the zero-sequence component. In other words, DG should not be directly ignored in the zero-sequence network, as its connection may cause distortion in the zero-sequence current. Consequently, significant differences may exist between the zero-sequence components of networks with and without DG. With increasing DG penetration, existing fault feeder detection methods may become ineffective. To address this issue, this paper proposes a fault feeder detection method suitable for distribution networks with high DG penetration. The main contributions are summarized as follows:

- Consideration of DG interference in the detection scheme design: During an SLG fault, the three sequence networks are connected in series at the fault point, and the harmonics generated by the DG in the positive-sequence network can affect the zero-sequence component. Hence, DG cannot be neglected when analysing zero-sequence fault characteristics, and the detection scheme should be applicable to SLG fault scenarios with or without DG connection.

- Extraction of polarity features and harmonic comparison between feeders: The variational mode decomposition (VMD) algorithm is used to obtain the low-frequency intrinsic mode functions (IMFs) of the ZSCs for each feeder. The cross-correlation of IMFs is employed as the primary detection criterion. Furthermore, considering the harmonic interference caused by high DG penetration, the derivative dynamic time warping (DDTW) distance of the harmonic body derivative is introduced as an auxiliary detection criterion. Finally, a comprehensive detection scheme is established based on both the primary and auxiliary criteria.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 analyzes the characteristics of the zero-sequence components during SLG faults in DG-connected distribution networks and reveals the DG-induced distortion. Section 3 presents a new fault feeder detection method that explicitly accounts for DG interference. Section 4 validates the fault analysis presented in Section 2 through simulation and field case studies. To further assess the proposed method’s detection performance, the simulation model, fault scenarios, and practical fault data are introduced, followed by comparative analyses. Finally, Section 5 concludes the study.

2. Transient Mechanism Analysis of High-Impedance Ground Fault

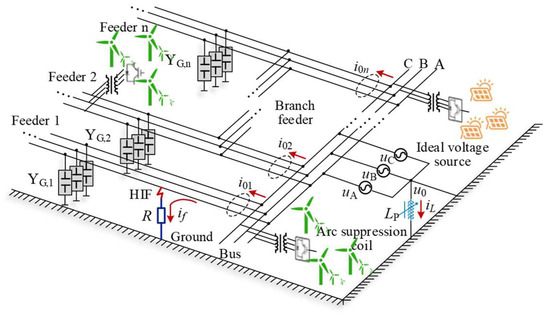

As shown in Figure 1, an HIF occurs on feeder 1 in a resonant-grounded active distribution network. The grounding resistance is denoted as R, and the arc suppression coil has an inductance of LP.

Figure 1.

The single-phase-to-ground HIF model of an active distribution network.

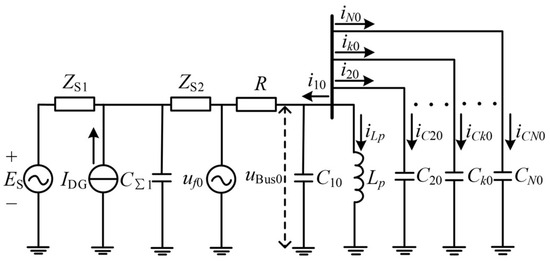

When an HIF occurs on Feeder 1 (connected to DG), although the DG branch is open in the zero-sequence network, the current source IDG in the positive-sequence network can still influence the ZSC on the feeder. The equivalent zero-sequence circuit is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Equivalent circuit model under HIF on feeder 1.

Where Zs1 and Zs2 represent the positive and negative-sequence equivalent impedances of the source branches, respectively. Ck0 is the zero-sequence capacitance of Feeder k, and denotes its capacitive zero-sequence current to ground. iCk0 is the ZSC flowing through Feeder k; iLp is the ZSC through the arc suppression coil; C∑1 denotes the total positive-sequence capacitance of all feeders. uf0 is the zero-sequence voltage (ZSV) at the fault point, while uBus0 is the busbar ZSV. The grounding resistance at the fault point is denoted as Rf. Under HIF conditions, R = 3Rf, and due to the low resonant frequency and relatively small inductance of the arc suppression coil, the inductive branch has a significant influence. The feeder inductance can be neglected, and the resonant behavior depends mainly on LP and the distributed capacitance Csum0.

Considering the harmonic distortion introduced by DG connections, IDG contains multiple frequency components, leading to harmonic interference at the fault point voltage uf0 = U0 sin (ω0t + φ0) + U1 sin (ω1t + φ1) + U2 sin (ω2t + φ2) +···+ Un sin (ωnt + φn). U0 sin (ω0t + φ0) represents the zero-sequence component generated by the source Es, where U0, ω0, and φ0 are its amplitude, angular frequency, and initial phase, respectively. Similarly, Ui sin (ωit + φi) are the harmonic components caused by IDG, with Ui, ωi, and φi representing the amplitude, frequency, and phase of each harmonic. The equations for ZSV and ZSC are given as follows:

In engineering practice, HIF resonance typically occurs under underdamped conditions. Applying the Laplace transform to Equations (1) and (2) and using the principle of superposition yields expressions for UBus0 (s), I10 (s), and Ik0 (s) [21], we have

The analysis indicates that for the faulty feeder 1, harmonics are mainly concentrated in the high-frequency range. Given this, the compensation effect of the arc suppression coil becomes negligible. Both the ZSV at the busbar and the ZSC of all feeders are contaminated with DG-induced harmonics. This implies that DG integration can significantly affect the zero-sequence components after an HIF occurs. The harmonics generated by DG propagate from the faulty feeder 1 to the healthy feeder k (k = 2, …, N), resulting in opposite ZSC polarities between the faulty and non-faulty feeders.

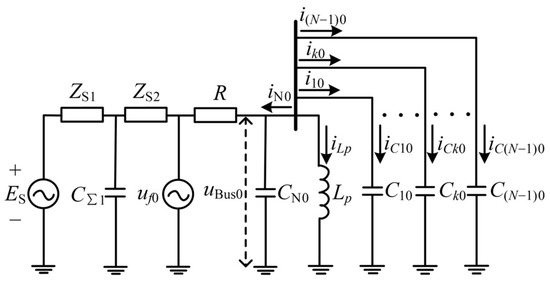

When an HIF occurs on a feeder N not connected to DG, and assuming the effects of upstream DG and downstream loads are negligible, the equivalent zero-sequence network is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Equivalent circuit model under HIF on feeder N.

The ZSV and ZSC equations for this scenario are expressed as follows:

Similarly, performing a Laplace transform and applying the superposition principle yields

The analysis reveals that even for feeder N without DG, the ZSC polarities between the faulty feeder and healthy feeders remain opposite. In summary, for single-phase HIF in DG-connected distribution networks, the presence of harmonic interference in the zero-sequence components depends on which feeder experiences the fault. If the HIF occurs on a feeder connected to DG, the ZSC will be affected by harmonics. If the fault occurs on a non-DG-connected feeder, such interference is absent. Nonetheless, the opposite polarity of ZSCs between the faulty and non-faulty feeders is consistently observed. Given that harmonic disturbances persist throughout the fault duration, significant distortion may be present in the ZSC during the transient stage. In the steady state, the ZSC of the faulty feeder generally contains more harmonic energy than that of the healthy feeders. Hence, the harmonic content of the ZSC may serve as a secondary indicator, aiding in the distinction between faulty and non-faulty feeders.

3. Faulty Feeder Detection Criteria

Based on the theoretical analysis, it is evident that during the transient stage of a fault, the ZSC polarities of faulty and healthy feeders are opposite. Additionally, if the ZSC is distorted due to DG connection, the harmonic content of the faulted feeder current becomes more pronounced in the steady state than that of healthy feeders. Therefore, both characteristics can be integrated into a composite detection criterion.

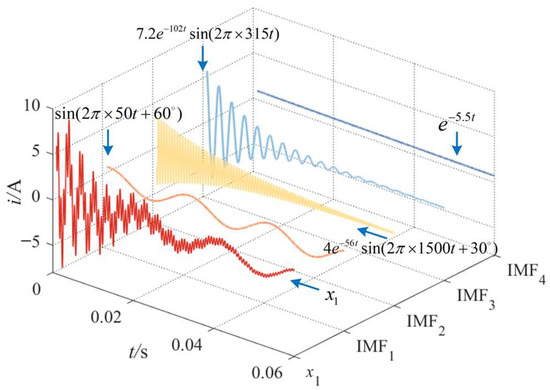

- Primary criterion: In distribution networks without DG connections, the transient zero-sequence component during an HIF primarily comprises the fundamental frequency, a DC component, and oscillatory decaying components at the natural resonance frequency [22]. However, when a single-phase-to-ground fault occurs on a DG-connected feeder, the transient ZSC is significantly distorted by harmonic components. In such cases, the original transient ZSC may not clearly reflect polarity characteristics. VMD is an effective adaptive signal decomposition tool that separates the original signal into multiple intrinsic mode functions (IMFs) [23]. When the number of decomposition modes is set to 2, VMD yields a low-frequency IMF1 representing the overall trend, and a high-frequency IMF2 representing detailed fluctuations. To illustrate the performance of VMD, consider the synthetic fault transient signal x1(t):

Figure 4.

VMD results of example signal x1.

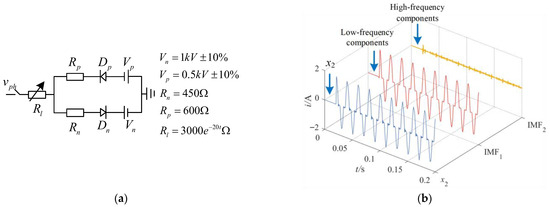

IMF1–IMF4 accurately capture the four distinct components within x1(t), without mode mixing, thereby verifying the effectiveness of VMD in handling transient fault signals. Additionally, using the HIF model in Figure 5a, the capability of VMD to isolate high-frequency components in a real HIF current signal x2(t) is assessed.

Figure 5.

VMD results of HIF current signal x2(t): (a) HIF model; (b) VMD results of signal x2(t).

As shown in Figure 5b, IMF1 captures the overall trend in the ZSC, accurately representing the low-frequency content of the HIF current, while IMF2 clearly reflects high-frequency components. This confirms that the VMD algorithm is effective for isolating high-frequency components in HIF signals. To characterize the polarity between feeders, cross-correlation analysis is used to compute the correlation coefficients of the IMF1 components of each feeder, as expressed in Equation (8):

where iIMF1,m and iIMF1,n are the IMF1 components of ZSC for Feeders m and n, respectively; p is the total number of samples; ρmn denotes the correlation coefficient between the ZSC of Feeders m and n. A negative correlation indicates opposite polarities, typical between the faulty and each healthy feeder, while healthy feeders exhibit positive correlation with one another. This allows the polarity of the correlation coefficient to serve as a distinguishing indicator of the faulted feeder.

- 2.

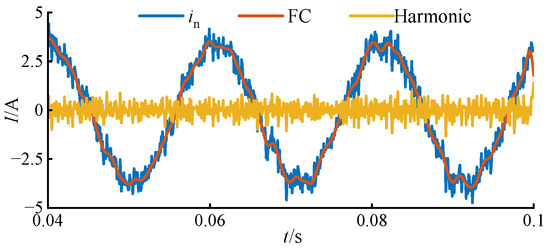

- Auxiliary criterion: In practice, the extracted IMF1 may fail to reflect polarity if the original signal is significantly distorted due to DG-induced harmonics, asynchronous sampling, data corruption, or varying signal lengths. Under such conditions, relying solely on the primary criterion may lead to misjudgment. To address this, an auxiliary HIF feeder detection criterion is proposed based on harmonic waveform similarity using the DDTW algorithm [24]. DDTW is capable of capturing dynamic variations in harmonic shapes by comparing the derivatives of the harmonic waveforms between feeders. Harmonic currents introduced by DG persist during the fault steady state. By subtracting the DC component—obtained via fast Fourier transform (FFT)—from the original signal, the harmonic signal can be extracted as follows:

Figure 6.

Zero-sequence current harmonic extraction results.

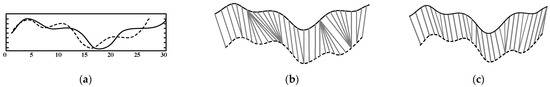

FFT effectively identifies the DC component, enabling accurate extraction of the harmonics. Figure 7 illustrates the alignment process of two arbitrary signals using both classical DTW and DDTW algorithms:

Figure 7.

Algorithm alignment procedures: (a) any two signals; (b) classic DTW algorithm alignment process; (c) DDTW algorithm alignment process.

It is evident that classical DTW may lead to singularity issues and redundant alignments during harmonic comparison. In contrast, DDTW introduces slope constraints during dynamic programming, reducing misalignment. Assume that the extracted harmonic waveforms are Q = q1, q2, …qi, …qn, and C = c1, c2, …cj, …cm. A cost matrix of size n × m is constructed, where each element represents the squared difference of the derivatives between qi and cj, computed as d (qi, cj) = (Dx [q]i − Dx [c]j)2. The estimated derivative formula is as follows:

The accumulated distance γ (i, j), representing the optimal alignment cost up to point (i, j), is defined as follows:

where min [γ (i −1, j −1),γ (i −1, j),γ (i, j −1)] represents updating the cumulative distance from the optimal regularized path. By computing the value of min γ (i, j), the DDTW distance between harmonic waveforms is obtained. For a distribution network with n feeders, the detection matrix CCTW is defined as follows:

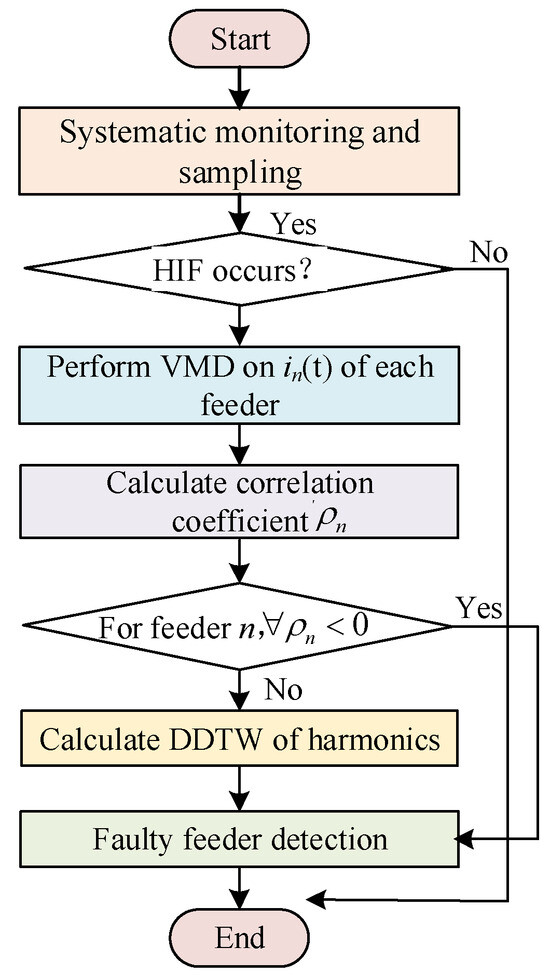

In this matrix, the lower triangular part represents the cross-correlation coefficients ρ between feeders, the diagonal elements are set to 1 (self-correlation), and the upper triangular part contains the DDTW distances between feeders. The overall HIF feeder detection procedure is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Flowchart of the HIF feeder detection criterion.

Specifically, when an HIF occurs, VMD is first used to compute the low-frequency IMF1 of each feeder’s ZSC. The cross-correlation coefficients are then calculated. If a feeder exhibits a negative correlation with all others, it is identified as the faulty feeder. If all correlation coefficients are positive, the event is considered a busbar fault. Otherwise, DDTW is applied to compare harmonic waveform similarity. If a feeder has the maximum DDTW distance from all others, it is determined to be the faulted feeder.

4. Simulation Testing and Experimental Validation

To comprehensively evaluate the proposed method, tests are conducted on a resonant-grounded distribution system (radial active distribution network), an improved IEEE-34 node distribution system with an ungrounded neutral point, and real-world field experiments.

4.1. Simulation Testing

4.1.1. Radial Distribution System

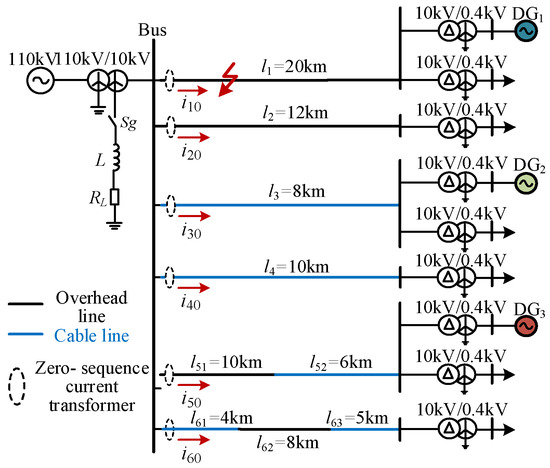

A radial active distribution network, as illustrated in Figure 9, is modelled in PSCAD/EMTDC. The system parameters are listed in Table 2 and Table 3. In Figure 9, RL and L represent the resistance and inductance of the arc suppression coil, respectively. The system neutral point is grounded via the arc suppression coil, with a compensation degree of 5%. Specifically, RL = 3.0662 Ω and L = 325.5 mH.

Figure 9.

Structure of a radial active distribution network.

Table 2.

Simulation model line parameters.

Table 3.

Parameters of DG.

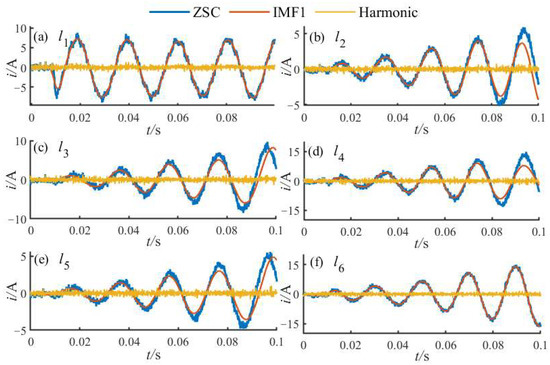

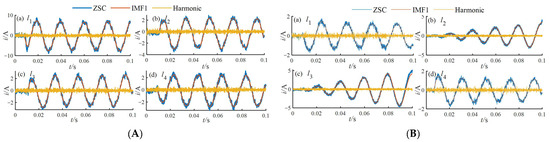

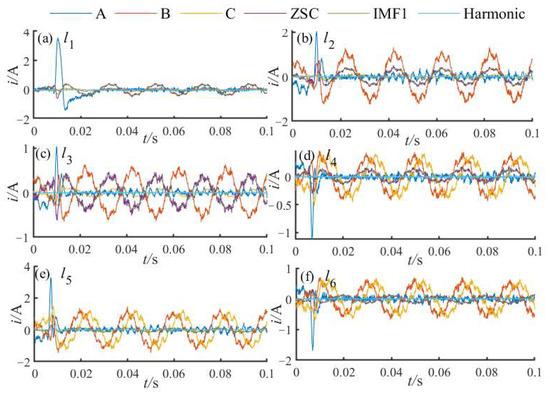

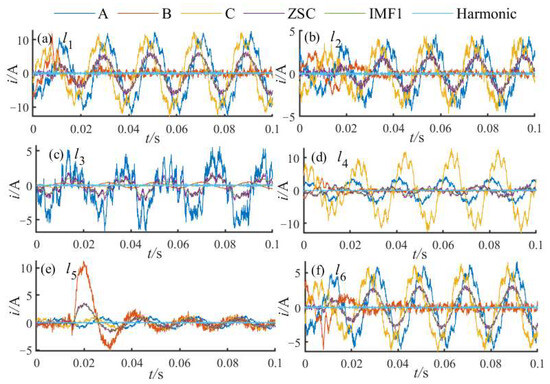

To better align with practical engineering conditions, the sampling frequency is set to 12.8 kHz, and random noise is added during sampling. When a single-phase HIF with an initial fault angle of 60° and a fault resistance of 2 kΩ occurs at 5 km along feeder l1, the ZSC, low-frequency IMF1, and harmonic components of feeders l1 to l6 are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Current components of each feeder.

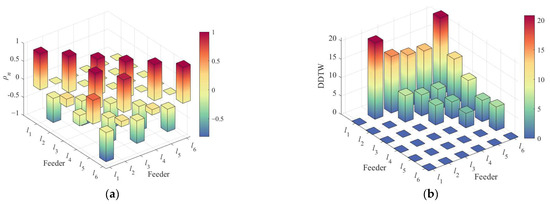

The computed detection criterion matrix CCTW is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

The HIF detection criterion CCTW for feeder l1.

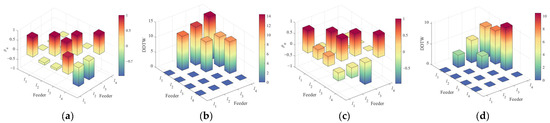

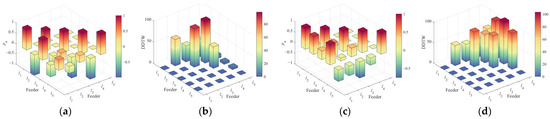

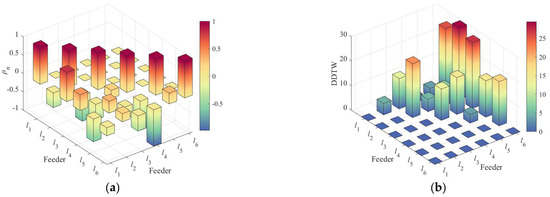

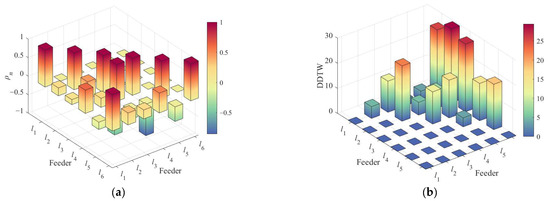

A visual representation of the CCTW matrix is provided in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

CCTW graph of fault on feeder l1: (a) correlation coefficient ρmn; (b) DDTW distance.

From the first column of the CCTW matrix, it is observed that the ρ between the faulty feeder l1 and the healthy feeders l2, l4, and l6 are negative: ρ21 = −0.6702, ρ41 = −0.2862, and ρ61 = −0.8097. However, the correlation coefficients between l1 and feeders l3 and l5 are positive: ρ31 = 0.2157 and ρ51 = 0.6591. Furthermore, the correlation coefficients between healthy feeders l3, l5 and l2, l4, l6 are negative, while ρ53 = 8996. These results, clearly visualized in Figure 11a, indicate that feeders l3 and l5, which are connected to DG, are affected by harmonic interference. If only the primary detection criterion is used, it would falsely identify l1, l3, and l5 as faulty, resulting in a misjudgment. Therefore, it is necessary to calculate the DDTW distances as an auxiliary criterion. As shown in Figure 11b, the DDTW distances between the faulted feeder l1 and all healthy feeders are significantly larger than those among the healthy feeders themselves. According to the proposed detection criterion, feeder l1 is thus correctly identified as the faulted feeder, demonstrating the method’s accuracy.

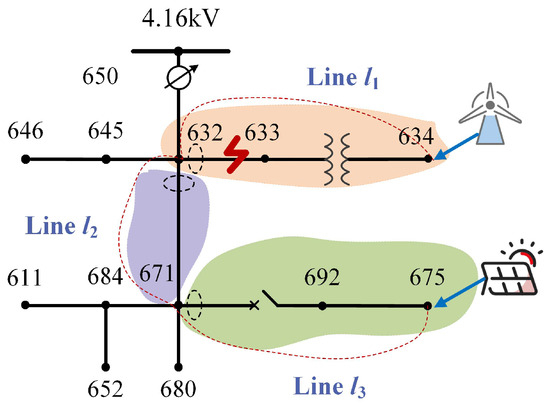

4.1.2. Modified IEEE-13 Node Distribution System

Building upon the radial active distribution network, a modified IEEE-13 node distribution system, as shown in Figure 12, is used for verification. The system operates at 4.16 kV, with DG connected at nodes 634 and 675.

Figure 12.

Improved IEEE 13-node distribution network model.

The system contains four feeders. Two HIFs are introduced: a 2 kΩ phase-A HIF at node 633 on feeder l1, and a 4 kΩ phase-C HIF at node 684 on feeder l4. The ZSC, low-frequency IMFs, and harmonic components of each feeder are illustrated in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Current components of each faulty feeder: (A) feeder l1; (B) feeder l4.

Table 5.

The HIF detection criterion CCTW for feeder l1.

Table 6.

The HIF detection criterion CCTW for feeder l4.

A visual representation of the CCTW matrix is provided in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

CCTW graph of fault on each feeder: (a) correlation coefficient ρmn of feeder l1; (b) DDTW distance of feeder l1; (c) correlation coefficient ρmn of feeder l4; (d) DDTW distance of feeder l4.

Figure 14 presents the correlation coefficients ρ and DDTW distances between feeders. When a fault occurs on feeder l1, the correlation values are ρ12 = −0.1136 and ρ13 = −0.0918 between l1 and feeders l2 and l3, respectively. However, due to harmonic interference, ρ14 = 0.8881 between l1 and feeder l4. According to the CCTW matrix, the DDTW distances between l1 and the healthy feeders are the highest, thus feeder l1 is accurately identified as the faulted feeder. When a fault occurs on feeder l4, the correlation values between l4 and the healthy feeders are all negative: ρ14 = −0.3598, ρ24 = −0.4619, and ρ34 = −0.4708. This indicates that the healthy feeders are unaffected by harmonics. Based on the primary detection criterion, feeder l4 is correctly identified as the faulty feeder.

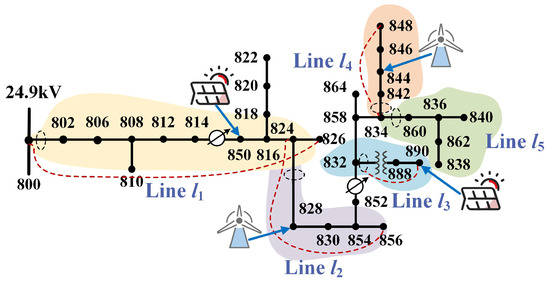

4.1.3. Modified IEEE-34 Node Distribution System

The modified IEEE-34 node distribution system, shown in Figure 15, is used for further verification. This system operates at a rated voltage of 24.9 kV, with the three-phase lines divided into five feeders. Distributed generators are connected at nodes 828, 844, 850, and 890.

Figure 15.

Improved IEEE 34-node distribution network model.

Under both resonant-grounded and ungrounded neutral configurations, two high-impedance faults are simulated: a 6 kΩ phase-B HIF at node 828 on feeder l2, and a 3 kΩ phase-A HIF at node 836 on feeder l5. The ZSC, low-frequency IMFs, and harmonic components of each feeder are shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Current components of each faulty feeder: (A) feeder l2; (B) feeder l5.

Table 7.

The HIF detection criterion CCTW for feeder l2.

Table 8.

The HIF detection criterion CCTW for feeder l5.

A visual representation of the CCTW matrix is provided in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

CCTW graph of fault on each feeder: (a) correlation coefficient ρmn of feeder l2; (b) DDTW distance of feeder l2; (c) correlation coefficient ρmn of feeder l5; (d) DDTW distance of feeder l5.

Analysis shows that when feeder l2 is faulted, the correlation coefficient ρ24 = 0.4028 due to harmonic interference, while the correlation values between l2 and other feeders are all negative. From the DDTW results, the DDTW distances between l2 and the healthy feeders are the largest. Based on the detection criteria, feeder l2 is correctly identified as the faulted feeder. When a fault occurs on feeder l5, the correlation values with the other feeders are all negative: ρ15 = −0.5381, ρ25 = −0.4560, ρ35 = −0.7532, and ρ45 = −0.3378, while all other inter-feeder correlations are positive. This indicates that the healthy feeders are not affected by harmonics. As such, feeder l5 is accurately identified as the faulted feeder.

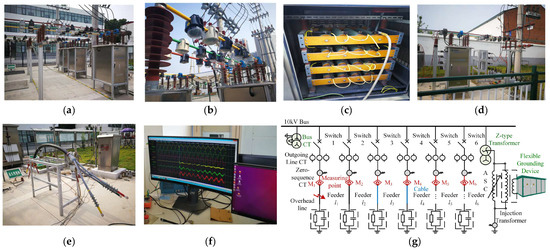

4.2. Field Experiments

The field experiments were conducted in the 10 kV distribution network full-scale experimental laboratory located in Shanxi Province, and the experimental topology is illustrated in Figure 18g. Fault indicators with a sampling frequency of 12.8 kHz were installed at measurement points M1–M6 to record the three-phase currents and zero-sequence currents. Feeders l1 and l2 are indoor overhead lines with lengths of 3 km and 4 km, respectively, while feeders l3 and l4 are indoor cable lines with lengths of 5 km and 6 km. Feeders l5 and l6, with lengths of 4 km and 3.5 km, are outdoor experimental lines used to perform arc-grounding, grass-grounding, and pond-grounding fault tests.

Figure 18.

10 kV distribution network experimental site and topology: (a) test control system; (b) measurement devices; (c) HIF; (d) grassland grounding; (e) arc grounding; (f) fault recording; (g) experimental topology.

The neutral grounding mode of the experimental system can be switched among low-resistance grounding, arc-suppression coil grounding, and ungrounded configurations. In addition to HIF tests, experiments involving arc-grounding, grass-grounding, and pond-grounding conditions were also conducted to verify the robustness of the proposed detection method. The experimental setups for the HIF, grass-grounding, and arc-grounding conditions are shown in Figure 18c–e.

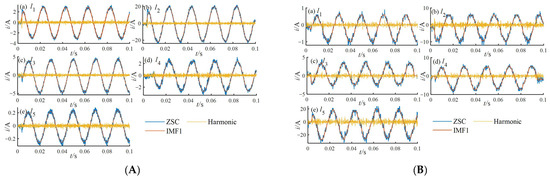

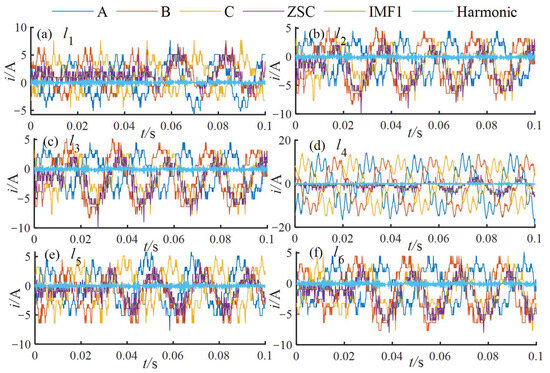

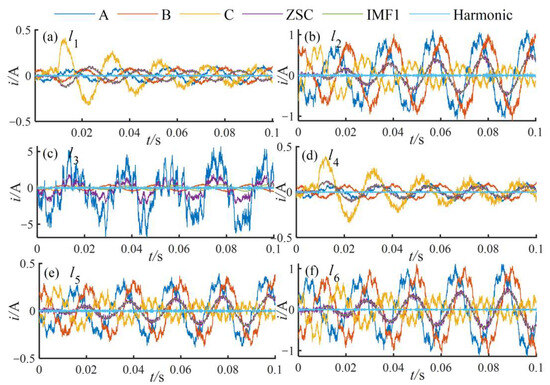

Under ungrounded neutral conditions, a 4 kΩ phase-B HIF was applied 2 km along feeder l1 with an initial fault angle of 30°. The three-phase currents, ZSC, low-frequency IMFs, and harmonic components of all feeders are shown in Figure 19.

Figure 19.

Current components of each feeder under HIF.

The computed detection criterion matrix CCTW is presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

The HIF detection criterion CCTW for feeder l1.

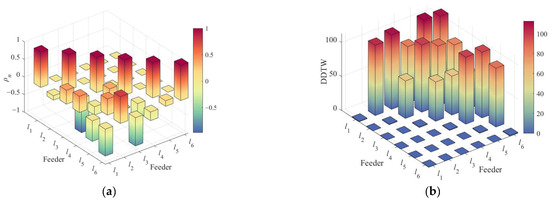

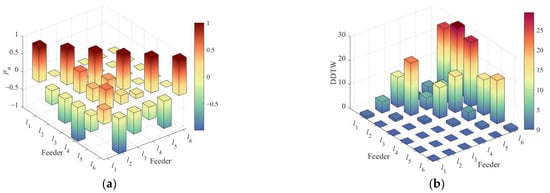

A visual representation of the CCTW matrix is provided in Figure 20.

Figure 20.

CCTW graph of fault on feeder l1: (a) correlation coefficient ρmn; (b) DDTW distance.

As shown in Table 8, due to harmonic interference, the correlation coefficients between feeder l1 and other feeders are ρ13 = 0.3927, ρ14 = 0.4597, and ρ16 = 0.7644. All other ρ between l1 and healthy feeders are negative. Meanwhile, the DDTW distances between the faulted feeder l1 and the healthy feeders are all the largest. Based on the auxiliary detection criterion, l1 is accurately identified as the faulted feeder. Under the 2Ω resistance-grounded condition, a phase-A arc grounding fault was applied to feeder l5. The corresponding three-phase currents, ZSC, low-frequency IMF, and harmonic components are shown in Figure 21.

Figure 21.

Current components of each feeder under arc grounding fault.

The computed detection criterion matrix CCTW is presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

The HIF detection criterion CCTW for feeder l5.

A visual representation of the CCTW matrix is provided in Figure 22.

Figure 22.

CCTW graph of fault on feeder l5: (a) Correlation coefficient ρmn; (b) DDTW distance.

Further analysis reveals that when feeder l5 experiences a fault, the correlation coefficients ρ25 = 0.3225 and ρ56 = 0.2933 indicate that feeders l2 and l6 are affected by harmonic interference. The DDTW distances between the faulted feeder l5 and the remaining feeders are all the largest, and based on the detection criterion, l5 is correctly identified as the faulted feeder. When feeder l6 undergoes a phase-C grassland grounding fault under arc-suppression coil grounding, the three-phase current, ZSC, low-frequency IMF, and harmonic components for all feeders are shown in Figure 23.

Figure 23.

Current components of each feeder under the grassland grounding fault.

The computed detection criterion matrix CCTW is presented in Table 11.

Table 11.

The HIF detection criterion CCTW for feeder l6.

A visual representation of the CCTW matrix is provided in Figure 24.

Figure 24.

CCTW graph of fault on feeder l6: (a) correlation coefficient ρmn; (b) DDTW distance.

In this case, ρ61 = 0.3973, while the correlation coefficients between l6 and the other feeders are all negative, suggesting that only feeder l1 is affected by harmonic interference. According to the DDTW values, the faulted feeder l6 shows the largest distances from all other feeders; thus, l6 is accurately identified as the faulted feeder. Under ungrounded neutral conditions, a phase-B pond grounding fault is introduced on feeder l5. The corresponding three-phase current, ZSC, low-frequency IMF, and harmonic components are presented in Figure 25.

Figure 25.

Current components of each feeder under the pond grounding fault.

The computed detection criterion matrix CCTW is presented in Table 12.

Table 12.

The HIF detection criterion CCTW for feeder l5.

A visual representation of the CCTW matrix is provided in Figure 26.

Figure 26.

CCTW graph of fault on feeder l5: (a) correlation coefficient ρn; (b) DDTW distance.

The correlation coefficients in this scenario are: ρ51 = −0.1973, ρ52 = −0.5081, ρ53 = −0.2561, ρ54 = −0.8501, and ρ56 = −0.3932. All ρmn between the faulted feeder and the others are negative, satisfying the primary detection criterion, thereby confirming l5 as the faulted feeder. These experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method not only accurately detects HIF but also reliably identifies faulty feeders under arc-grounding, grassland-grounding, and pond-grounding conditions, exhibiting strong robustness and adaptability.

4.3. Comparison with Existing Methods

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, experiments were conducted in the 10 kV distribution network full-scale experimental laboratory under different conditions using the field experimental topology and measured data. Three test conditions were considered: A. grounding resistance of 2000 Ω with a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 5 dB; B. grounding resistance of 3000 Ω with an SNR of 3 dB; and C. arc fault condition. Under conditions A and B, a SLG occurred on feeder l1, whereas under condition C, an arc fault was introduced on feeder l5. The proposed method was compared with several existing approaches, namely the first half-wave polarity method [25], the correlation analysis method [26], the maximum energy method [27], and the dynamic voltage–current characteristic method [28]. The detection results are summarized in Table 13.

Table 13.

Detection results by different methods.

Due to the minimal waveform differences in the first half-cycle between the faulted and healthy feeders, the polarity-based detection often fails—the polarity of the healthy feeder’s waveform is difficult to ascertain, leading to incorrect fault identification. According to the criterion in [26], the correlation analysis method determines the faulty feeder as the one corresponding to the minimum ρ value when the range ρmax − ρmin > 0.20. However, as seen in Table 13, under HIF conditions with data window lengths of 5 ms, 10 ms, and 20 ms, this method gives incorrect results. This is because the correlation method uses post-fault current waveforms within 0.25–1 cycles, which reflect macro-level features susceptible to waveform distortion. In cases where the fault occurs at the end of an overhead line and the healthy feeder is a cable, the fault current magnitude may be lower than that of the cable feeder. Under HIF conditions, this significantly distorts the initial polarity, leading to frequent misjudgment using the correlation method. The method of [25] is capable of detecting arc faults; however, it fails when the grounding resistance is excessively high or the noise level is severe. Similarly, the method presented in [26] is unable to identify the faulted feeder under high-impedance or strong-noise conditions. The proposed CCTW criterion, which integrates the ZSC correlation coefficient and DDTW distance, captures the fault characteristics from a microscopic perspective. It reveals the intrinsic difference in the matching behavior of ZSC direction and harmonic waveform similarity between faulted and healthy feeders, thus achieving accurate detection results.

Furthermore, the computational complexity and scalability of the proposed method were analyzed. Specifically, the main operations involve VMD and correlation analysis, yielding an overall computational complexity of approximately O (N·k), where N denotes the number of sampling points and k the number of decomposition modes (N = 1280, k = 2 in the proposed). Compared with data-driven deep learning approaches, the proposed method requires significantly fewer parameters and lower computational resources, making it suitable for real-time deployment in feeder terminal units (FTUs) or distribution management systems (DMSs).

5. Conclusions

This paper addresses the issue of low detection accuracy of HIF feeders in resonant grounded active distribution systems and proposes a faulted feeder detection method based on ZSC cross-correlation polarity analysis and harmonic waveform similarity matching. The main conclusions are as follows:

- The ZSC characteristics of the distribution network with DG under HIF conditions were analyzed. The polarity differences among feeder ZSCs were revealed, leading to the conclusion that when DG is connected to the faulted feeder, the generated harmonics cause ZSC distortion.

- The VMD algorithm was employed to extract the low-frequency components of feeder ZSCs, and the cross-correlation analysis was adopted as the primary detection criterion to capture polarity features among feeders. Furthermore, when ZSC distortion is severe due to DG connection, the harmonic characteristics of ZSCs are utilized to construct an auxiliary criterion.

- Simulation and field experiments demonstrated that, under HIF conditions, the proposed detection criteria are unaffected by grounding resistance, initial fault phase angle, or strong noise interference. The method remains applicable under arc, grass, and pond grounding scenarios, accurately identifying the faulted feeder. Compared with existing methods, the proposed approach offers computational simplicity, stable performance, and strong potential for engineering applications.

Future work will focus on further enhancing the adaptability of the proposed method under multi-source integration and complex operating conditions. Deep learning techniques will be incorporated for intelligent feature extraction and parameter self-optimization. Moreover, multi-source information fusion will be explored to establish comprehensive fault detection criteria, and studies on online and embedded implementation will be conducted to promote practical deployment in active distribution systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H. and T.L.; methodology, S.H.; software, T.L.; validation, T.L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.L.; writing—review and editing, S.H.; visualization, T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by State Grid Shanxi Electric Power Company through “Research on fault type identification and localization technology of distribution network based on multi-dimensional features”, grant number 5205M0230008.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HIF | High-impedance fault |

| DG | Distributed generation |

| SLG | Single line-to-ground |

| ZSC | Zero-sequence current |

| VMD | Variational mode decomposition |

| IMFs | Intrinsic mode functions |

| DDTW | Derivative dynamic time warping |

| FFT | Fast Fourier transform |

References

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Gao, J.; Wei, X. Faulty Feeder Detection under High Impedance Fault for Active Distribution Network in Resonant Grounding Mode. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 3530811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Ji, J.; Zhang, M.; Gong, Y. Active High-Impedance Fault Detection Method for Resonant Grounding Distribution Networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 10932–10945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, J.; Hu, Z.; Han, X.; Zhou, X. Faulty Feeder Detection Based on Grey Correlation Degree of Adaptive Frequency Band in Resonant Grounding Distribution System. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yan, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, X.; Peng, X.; Yuan, H. Research on Correlation Factor Analysis and Prediction Method of Overhead Transmission Line Defect State Based on Association Rule Mining and RBF-SVM. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Deng, Z.; Wu, J.; Chen, K.; Jia, P. Fault Nature Identification and Location Scheme for Distribution Network Based on Active Injection from IIDG. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 156, 109706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Wang, X.; Gao, J.; Yang, D.; Wei, K.; Guo, L. Faulty Feeder Detection for Single-Phase-to-Ground Fault in Distribution Networks Based on Transient Energy and Cosine Similarity. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2022, 37, 3968–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Lu, J.; Yu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wang, K. A Two-Stage Fault Localization Method for Active Distribution Networks Based on COA-SVM Model and Cosine Similarity. Electronics 2024, 13, 3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Cui, X. Nonlinear Modeling Analysis and Arc High-Impedance Faults Detection in Active Distribution Networks with Neutral Grounding via Petersen Coil. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 1888–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogula, V.; Edward, B. Advanced Signal Analysis for High-Impedance Fault Detection in Distribution Systems: A Dynamic Hilbert Transform Method. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1365538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Peng, K.; Gao, Q.; Feng, L.; Xiao, C. Series arc Fault Identification Method Based on Wavelet Transform and Feature Values Decomposition Fusion DNN. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 221, 109391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Qu, N.; Zheng, T.; Hu, C. Series arc Fault Detection Based on Wavelet Compression Reconstruction data Enhancement and Deep Residual Network. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 3508409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Wei, Z. Fa-Mb-ResNet for Grounding Fault Identification and Line Selection in the Distribution Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 11115–11125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mampilly, B.; Sheeba, V. An Empirical Wavelet Transform Based Fault Detection and Hybrid Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network for Fault Classification in Distribution Network Integrated Power System. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 77445–77468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsaif, Y.M.; Lipu, M.S.H.; Hussain, A.; Ayob, A.; Yusof, Y.; Zainuri, M. A New Voltage Based Fault Detection Technique for Distribution Network Connected to Photovoltaic Sources Using Variational Mode Decomposition Integrated Ensemble Bagged Trees Approach. Energies 2022, 15, 7762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Gao, J.; Li, W.; Wang, K.; Guo, M. Detection of High-Impedance Fault in Distribution Networks using Frequency-Band Energy Curve. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 24, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Liu, H. Overlap Functions-Based Fuzzy Mathematical Morphological Operators and Their Applications in Image Edge Extraction. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Liu, W.; Zhang, H.; Shi, F.; Chen, W. Distortion-Based Detection of High Impedance Fault in Distribution Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2020, 36, 1603–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Tang, J.; Shi, S.; Cai, D.; Zhang, L.; Xiong, P. Fault Diagnosis Techniques for Electrical Distribution Network Based on Artificial Intelligence and Signal Processing: A review. Processes 2024, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Bai, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, N. Research on a Faulty Line Selection Method Based on the Zero-Sequence Disturbance Power of Resonant Grounded Distribution Networks. Energies 2019, 12, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, S.; Rajeev, P.; Gad, E. Power distribution system faults and wildfires: Mechanisms and prevention. Forests 2023, 14, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Hu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Jiao, Z. Faulty feeder detection for single line-to-ground fault in distribution networks with DGs based on correlation analysis and harmonics energy. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2022, 38, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Yang, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Gao, J.; Wei, K. Faulty Feeder Detection Based on Fundamental Component Shift and Multiple-Transient-Feature Fusion in Distribution Networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 12, 1699–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wu, J. Low-Voltage arc Fault Identification Using a Hybrid Method Based on Improved Salp Swarm Algorithm–Variational Mode Decomposition–Random Forest. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 15410–15418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Bao, W.; Liao, C.; Chen, D.; Hu, H. Corn phenology detection using the derivative dynamic time warping method and sentinel-2 time series. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhniya, H.; Madani, S.-M.; Parvaresh, F. High Impedance Faults Detection in Distribution Systems Using Signal Correlations. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 9001909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, M.; Gargoom, A.; Mahmud, M.; Haque, M.; Al-Khalidi, H.; Oo, A. A Decentralized Fault Detection Technique for Detecting Single Phase to Ground Faults in Power Distribution Systems with Resonant Grounding. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2018, 33, 2462–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Zhuo, F.; Mohamed, M. A novel approach based on CEEMDAN to select the faulty feeder in neutral resonant grounded distribution systems. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2019, 69, 4712–4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Geng, J.; Dong, X. High-impedance fault detection based on nonlinear voltage–current characteristic profile identification. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 9, 3783–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).