Abstract

Android operating system (OS) has been recently featured as the most commonly used and ingratiated OS for smartphone ecosystems. This is due to its high interoperability as an open-source platform and its compatibility with all the major browsers within the mobile ecosystem. However, android is susceptible to a wide range of Spyware traffic that can endanger a mobile user in many ways, like password stealing and recording patterns of a user. This paper presents a spyware identification schemes for android systems making use of three different machine learning schemes, including fine decision trees (FDT), support vector machines (SVM), and the naïve Bayes classifier (NBC). The constructed models have been evaluated on a novel dataset (Spyware-Android 2022) using several performance measurement units such as accuracy, precision, and sensitivity. Our experimental simulation tests revealed the notability of the model-based FDT, making the peak accuracy 98.2%. The comparison with the state-of-art spyware identification models for android systems showed that our proposed model had improved the model’s accuracy by more than 18%.

1. Introduction

Spyware is malicious software that gathers information about individuals or organizations without their knowledge. It can be installed on a device through malware or downloaded from the internet [1]. Besides, spyware can target various internet of things (IoT) [2] and cyber-physical systems (CPS) [3] to steal information from victims and devices. Spyware can track a user’s online activity, record keystrokes, capture passwords and personal information, and even take control of the device’s camera and microphone [4]. On the other hand, android is an operating system designed for smartphones and developed by Google and the Open Handset Alliance. Android is known for its versatility and customization; it allows users to customize their home screens, widgets, and app icons. It also offers a wide range of features, including access to the Google Play Store, Google Maps, and Google Assistant [5]. One of the main advantages of android is its open-source nature, which allows developers to create and distribute their apps without the need for approval from a central authority [6].

This has contributed to the success and popularity of the android operating system [5]. According to Statista, as of November 2022, android devices make up most of the global smartphone market [7]. This increasing use of android doesn’t come without a cost. Its expanding services have exposed people to threats like spyware more than ever.

Like any malware, spyware can intrude in many forms, causing much harm to the user [8]. Since most information is stored on a mobile phone, it is a favorite spyware target. Spyware can endanger a mobile user in many ways, like password stealing and recording patterns of a user, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Major harms that spyware can cause to a mobile phone.

There are two prevalent methods to counter the surging spyware issues for android systems: the static and dynamic methods. The statistical method has proven to perform very well for already-known spyware, but for new variants, performance could be better [9]. The dynamic method includes data mining (D.M.) and ML techniques.

Studies suggest that machine learning (ML) can be an effective tool for identifying and detecting spyware [10]. A machine learning algorithm can be trained on a dataset of known spyware samples and benign software. The algorithm will learn to distinguish between them based on their characteristics and behavior [11]. Once trained, the algorithm can quickly and accurately analyze new software, detecting unknown types of spyware that may not be included in traditional malware databases [12]. However, it is also important to note that ML-based spyware detection can sometimes be erroneous and produce false positives or negatives [13].

Decision trees (D.T.), a type of ML algorithm, are a widely used technique for classifying malware in general and spyware in particular. D.T. uses a set of rules to classify data. They can handle large amounts of data and make decisions based on multiple factors [14]. This makes them particularly useful for android systems, which often have many apps and data points that need to be analyzed. In addition, decision trees can classify spyware variants with much higher accuracy and the least error [15]. However, it is important to note that decision trees can be prone to overfitting, in which the model gets trained for the current dataset only and incorrectly classifies future data [16]. This issue can be addressed through pruning, a technique that removes unnecessary tree branches and improves accuracy [17].

To overcome this shortcoming, this research has turned to fine decision trees (FDTs) for spyware identification. This research has proven that the use of fine decision trees for spyware identification on android systems has the potential to protect users from the negative consequences of this malware, including the theft of sensitive information and the disruption of normal device function. The main objective of this study is to provide a revolutionary methodology that, even in the face of tricky and evasive attacks, can successfully detect android spyware. The main advantage was the utilization of recently specialized datasets from the real-world environment to create more reliable and adaptive training and testing materials, which were then combined with different algorithms to create the most accurate and time-efficient model possible. The primary contribution of this paper is the proposal of a machine learning-based detection method for android spyware attacks using a specialized novel dataset. The following is a list of the specific contributions: (a) comparing a vast quantity of research to choose the most viable dataset and effective method; (b) rendering the qualified dataset for ease of use; and (c) achieving a binary classification with high accuracy.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a comprehensive review and summary of the existing state-of-the-art models for Android spyware detection. Section 3, the core section, presents the system model and the simulation results of the proposed spyware identification for android systems using fine trees. Finally, the last section, conclusions, provides a closing summary and remarks on the research article’s contributions.

2. Related Work

Spyware identification for android systems is an important research topic, as spyware can pose a mounting threat to individuals and organizations by collecting sensitive information and disrupting normal device functioning. In recent years, there has been a growing body of research on using ML algorithms for spyware identification on Android systems.

F. Pierazzi et al. [18] experimented with combining deep learning (DL) with static methods. The authors have proposed the ensemble late fusion (ELF) technique, which generates a final result based on predictions made by initial classifiers. They have also highlighted the distinguishing features of different spyware families and the features differentiating spyware from goodware and other malware. The model has achieved an accuracy of 98.2% for predicting whether the instance is goodware or spyware.

Another promising study by N.N. Gana et al. [19] uses an enhanced support vector machine (SVM). This research has overcome the poor performance problem of past SVMs by selecting optimal features. SVM has been re-calibrated by using symbiotic organisms search (SOS) to select features. As a result, the model classified spyware with an accuracy of 97.40%, while the false positive rate was just 2.3%.

M.K. Qablain et al. [20] have achieved astounding results using the random forest (R.F.) algorithm. They labeled their dataset in three ways: normal traffic, spyware traffic for installation, and spyware operation traffic. Their average accuracy was 79% for binary-class classification and 77% for multi-class classification. Still, the accuracy achieved has much room for improvement.

Since integrating various ML models is always a commendable way of doing research, the same has been done by M.N. AlJarrah et al. [21]. Six supervised ML algorithms have been used to classify the traffic as malware or normal. The algorithms employed are R.F., SVM, logistic regression (L.R.), naive Bayesian (N.B.), K-nearest neighbour (KNN), and D.T. Among these, D.T. and R.F. have the highest accuracy, at 87% each. Together, these models reached an accuracy of 99.4% with context-aware features and 97.2% without. This research needs feature selection, where only 50 features were selected among 527 features.

R. Kumar et al. [22] have improved D.T. Their experiment entails classifying traffic as malware or normal using XGboost gradient-boosted D.T. This model has performed outstandingly, requiring the least resources. The model was trained in just 1315 s. The accuracy it achieved was 98.5%. One thing still missing from this research is that it works for generalized malware and not specifically spyware detection.

Recent research has incorporated many ML models in its course. M.S. Akhtar et al. [11] have conducted their malware classification research. Their research has used many ML models and selected the best-performing ones. The models used in this research are NB, SVM, J48, R.F., D.T., and convolutional neural network (CNN). Regarding accuracy, D.T. achieved the highest result with a value of 99%; CNN could reach an accuracy of 98.76%, while SVM stood at 96.41%. As per the confusion matrix, D.T. only has a false-positive rate of 2.01%.

Another approach that has been explored is the use of ML algorithms for the classification of malware transmitted through Portable Document Format (PDF) [22]. The approach combines both static and dynamic methods of malware classification. In the aspect of ML, different algorithms have been used, such as R.F., SVM, and D.T. Among these, R.F. has the best performance, with an accuracy of 97.8%. Nevertheless, the research needs to be more proficient at classifying spyware specifically.

Furthermore, A.S. Shatnawi et al. [12] have devised yet another method of classifying malware on android systems. During the experiment, they investigated all the possible methods of malware classification, i.e., static, dynamic, and hybrid (a combination of static and hybrid). The authors have concluded that a static method is the best choice due to the cost-accuracy trade-off. But due to ever-increasing malware variants, the static method might not have adaptability.

Mahesh V. et al. [23] have contributed to this field’s research. They have investigated the issue of spyware detection using the DL model. They achieved an accuracy of 99.7%. This research is not aimed holistically at spyware detection on android systems but at classifying spyware if it is intended to harm a personal computer (P.C.) or a smartphone.

Using ML algorithms for spyware identification on android systems has several advantages. One advantage is that ML algorithms work with a plethora of data, making them the best choice for Android systems with numerous apps and data points [24]. This allows the models to effectively classify various types of spyware, including those that may have been modified or disguised to evade detection.

Another advantage of using ML for spyware identification on Android systems is that it can be automated and scalable, making it easier to protect against spyware on many devices. This is particularly important in organizations with many employees using mobile devices, as it can be time-consuming and resource-intensive to manually identify and remove spyware from each device. An overview of ML techniques used in literature has been given in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Summary of the various approaches for spyware and malware detection.

Table 2.

Summarizing some of the research surveyed in this paper.

In addition to these advantages, ML offers the benefit of adaptability. ML algorithms can learn and adapt to changing patterns in the data, which can be important in the dynamism of the spyware threat [8]. By continually updating the model and incorporating new data, it becomes possible to ensure that the model remains effective at identifying new types of spyware as they emerge.

It is good to note that there is no one-size-fits-all approach for spyware identification on android systems, and the best approach will depend on the specific needs and constraints of the situation. Machine learning algorithms may perform differently depending on the quality and diversity of the training data and the specific parameters and settings used [24]. Further research is needed to improve these approaches’ effectiveness and identify the best methods for protecting against spyware on android systems.

The results of these studies may vary depending on the specific approach, dataset, and evaluation methods used. Additionally, the performance of these approaches may change over time as the threat landscape of mobile spyware evolves. Further research is needed to continue improving the effectiveness of mobile spyware identification techniques and to identify the best approaches for protecting against this threat. It can be summarized by saying that using different ML algorithms for spyware identification on android systems is a promising area of research. While various approaches have been explored, each has its strengths and limitations. Further research is needed to improve these approaches’ effectiveness and identify the best methods for protecting against spyware on android systems. Indeed, several other interesting studies have been conducted for non-android and can be found in [25,26,27,28,29].

3. Identification, Modeling, and Evaluation

In this section, we discuss the system development methodology and the performance evaluation of the proposed model in terms of several factors.

3.1. The Identification Model

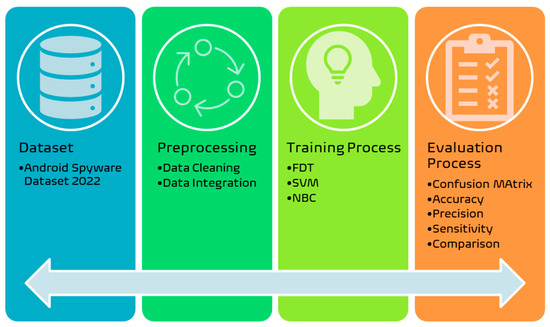

The proposed system model to identify the Android spyware is illustrated in Figure 2 below. The system comprises four main components: the dataset component, the preprocessing component, the training module, and the testing and evaluation module.

Figure 2.

Overall System Model for Android Spyware Identification.

- The Dataset: The used dataset (Spyware-Android 2022) [20] includes network traffic data for the most advanced spyware tools used for android, including MobileSPY and FlexSPY, in addition to the normal traffic samples. The dataset comprises seven features (sequence number, duration time, source address, destination address, target protocol type, traffic length, and additional information about the traffic behavior) and one target class (normal, MobileSPY, and FlexSPY). This dataset focuses on spyware systems that share a similar installation process, which was followed according to the instructions provided by the manufacturers. The data collection process involves both the spyware package information and transaction data. A crucial aspect of preparing the dataset for this research was creating a high-quality benchmark, which was accomplished by evaluating the dataset based on established criteria. The benchmark must be objectively interpreted, comparable, and repeatable to ensure validity. The usefulness of benchmarks is maximized when they accurately reflect real-world scenarios. Then the machine learning model was trained using this dataset. So, its accuracy is, in fact, its real-world performance matrix. Furthermore, this research is very novel and focused on detecting spyware for android. The existing security systems are very concerned about spyware, specifically its detection, let alone android spyware; this model would feature detecting android spyware using the random forest machine learning model with very reasonable accuracy. Such a model has never been proposed in the literature. This reach adds a commendable dataset and a model for accurately classifying android spyware to the existing security systems. The dataset used for this experiment was acquired from the most common spyware applications that are available commercially. All the spyware’s features were activated. The dataset was recorded using a packet sniffer tool that operated on android. The tool used was PCAPDroid. The dataset contains data in CSV as well as PCAP format. The data has three classes: class A has the normal traffic data; class B has the instances of spyware installation traffic; and class C has the typical spyware traffic.

- The preprocessing stage: In this stage, we have checked the validity of all data samples, fixed all errors in the data records, encoded all categorical data, compensated all null values with zeros, and removed all duplications. We have also integrated all samples from the dataset for each class into one common file in a randomized manner in order to be trained at the next stages of the model.

- The training module: In this module, in order to build up a comparative study, we have constructed the training model using three different machine learning methods, including fine decision trees (FDT), support vector machines (SVM) [30], and the naïve Bayes classifier (NBC). The three models have been established and trained using 75% of the samples in the overall dataset. The remaining 25% of the samples have been used to test (validate) the model’s predictability for unseen data samples. Also, 5-fold cross-validation has been used at the validation stage to ensure an efficient validation procedure [31].

- The evaluation process is conducted to measure the model’s performance in spyware identification for android systems using the different training models (FDT, SVM, and NBC) in terms of accuracy, precision, and sensitivity. This will end up with comparative results between the three machine learning models, of which one is selected as the best-performing model.

3.2. The System Evaluation

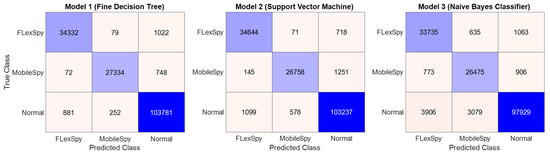

Figure 3 visualizes the three subfigures for the confusion matrix analysis for each established model: (a) analyzing the ternary classifier of spyware identification for android systems using the FDT model; (b) analyzing the ternary classifier of spyware identification for android systems using the SVM model; and (c) analyzing the ternary classifier of spyware identification for android systems using the NBC model. According to the figure, all models have effectively identified the android spyware, with misclassification rates of 3054 samples out of 168,501 (1.812%), 3054 samples out of 168,501 (1.812%), 3862 samples out of 168,501 (2.292%), 3054 samples out of 168,501 (1.812%), and 10,380 samples out of 168,501 (6.161%). Thus, one can observe that the FDT model has better outcomes than the other models in correctly classified samples (T.P. + T.N.).

Figure 3.

This is a figure. Schemes follow the same formatting.

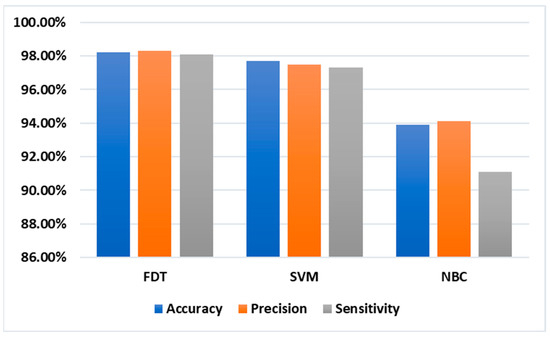

Table 3, along with Figure 4, presents the results obtained from testing and evaluating the three stated models using three typical measurements: identification accuracy, precision, and sensitivity. Accordingly, FDT has registered the highest accuracy measurements, with an accuracy of 0.5% and 4.3% higher than that for SVM and NBC-based models. Also, FDT has registered the highest precision measurements, with a precision of 0.8% and 4.2% higher than that for SVM and NBC-based models. Moreover, FDT has registered the highest sensitivity measurements, with a sensitivity of 0.8% and 7.0% higher than that for SVM and NBC-based models. Besides, to provide a better idea of the performance of FDT, we have applied two tree-based algorithms, including Adaboost and random forest, where both of them scored a performance lower than FDT, with 97.3% and 96.7% of accuracy recorded for Adaboost and random forest, respectively. Finally, it can be clearly noted that the FDT model has better outcomes than the other models in terms of performance measurements. This supremacy of FDT over other classifiers can be justified as they adapt quickly to the dataset due to the large number of splits using Gini’s diversity index (this is why they are called fine trees). The final model can be viewed and interpreted in an orderly manner using a “tree” diagram.

Table 3.

System evaluation using three machine learning techniques: FDT, SVM, and NBC, in terms of classification accuracy, precision, and sensitivity. Classifier.

Figure 4.

System evaluation using three machine learning techniques: FDT, SVM, and NBC, in terms of classification accuracy, precision, and sensitivity. Classifier.

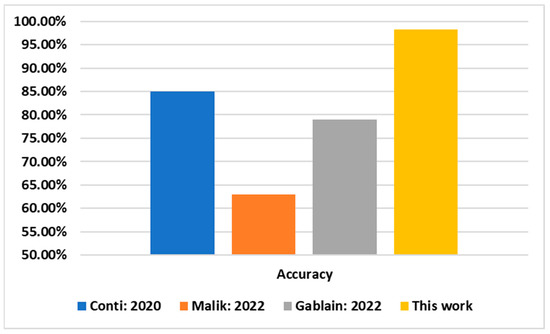

Table 4, along with Figure 5, presents the comparison results obtained from comparing our best performance results (i.e., obtained by the FDT model) with the other existing state-of-the art models for spyware identification for android systems using different machine learning methods. The comparison takes into consideration the machine learning scheme utilized to develop each spyware identification system, the number of classes, considering one class for normal traffic and the other classes for the various spyware traffic, and finally, the vital factor to judge between the systems, namely, the model accuracy. Our model seems eminent by achieving elevated accuracy over existing spyware identification systems.

Table 4.

Comparing classification accuracy with other existing models for spyware detection.

Figure 5.

Comparing classification accuracy of this model with other existing models for spyware detection.

Even though the proposed study identified well-performing models, the main research limitations of this study are: (a) additional validation is required for the proposed model, (b) the robustness of this model’s immunity against spyware obfuscation techniques is not fully elucidated, and (c) the hardware impediments impacted the training time results.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

An independent new scheme for spyware identification in android-based systems using machine learning is proposed and discussed in this paper. The model contrasts the performance of three different machine learning schemes, including fine decision trees (FDT), support vector machines (SVM), and the naïve Bayes classifier (NBC). The constructed models have been evaluated on a novel dataset (Spyware-Android 2022) using several performance measurement units such as accuracy, precision, and sensitivity. The simulation assessments showed the notability of the model-based FDT, making the peak accuracy 98.2%. The comparison with the state-of-the-art spyware identification models for android systems showed that our proposed model had improved the model’s accuracy by more than 18%. In the future, we will examine more malware types, such as botnet attacks [34]. Also, we will investigate more android spyware types by incorporating more datasets into the study [35]. Moreover, we will seek to apply the knowledge of deep and hybrid learning techniques to improve the predictability of zero-day attacks [36]. Furthermore, we will study how the proposed model would perform with different types of spyware beyond MobileSPY and FlexSPY to avoid several other Android problems [37].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N. and Q.A.A.-H.; methodology, Q.A.A.-H., software, Q.A.A.-H.; validation, M.N. and Q.A.A.-H.; formal analysis, Q.A.A.-H.; investigation, M.N. and Q.A.A.-H.; resources, M.N. and Q.A.A.-H.; data curation, M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N. and Q.A.A.-H.; writing—review and editing, M.N. and Q.A.A.-H.; visualization, Q.A.A.-H.; funding acquisition, M.N. and Q.A.A.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data associated with this article is publicly available through the Mendeley data repository and can be retrieved from: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/mhvgtywrxf/1 (accessed on 22 November 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Grimmelmann, J. Spyware vs. Spyware: Software Conflicts and User Autonomy. Ohio St. Tech. LJ. 2020, 16, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Albulayhi, K.; Smadi, A.A.; Sheldon, F.T.; Abercrombie, R.K. IoT Intrusion Detection Taxonomy, Reference Architecture, and Analyses. Sensors 2021, 21, 6432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smadi, A.A.; Ajao, B.T.; Johnson, B.K.; Lei, H.; Chakhchoukh, Y.; Abu Al-Haija, Q. A Comprehensive Survey on Cyber-Physical Smart Grid Testbed Architectures: Requirements and Challenges. Electronics 2021, 10, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspersky. Spyware Definition. 2022. Available online: https://www.kaspersky.com/resource-center/threats/spyware (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Gilski, P.; Stefanski, J. Android os: A review. Tem J. 2015, 4, 116. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, C.S.; Singh, J.; Yadav, A.; Pattanayak, H.S.; Kumar, R.; Khan, A.A.; Haq, M.A.; Alhussen, A.; Alharby, S. Malware Analysis in IoT & Android Systems with Defensive Mechanism. Electronics 2022, 11, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Android Authority. Opportunity Powered by Choice. 2020. Available online: https://www.android.com/everyone/enabling-opportunity/ (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Al-Haija, Q.A.; Saleh, E.; Alnabhan, M. Detecting Port Scan Attacks Using Logistic Regression. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Advanced Electrical and Communication Technologies (ISAECT), Alkhobar, Saudi Arabia, 6–8 December 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laricchia, F. Mobile Operating Systems’ Market Share Worldwide from 1st Quarter 2009 to 4th Quarter 2022. 16 November 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/markets/418/topic/481/telecommunications/ (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Shahzad, R.K.; Haider, S.I.; Lavesson, N. Detection of Spyware by Mining Executable Files. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, Krakow, Poland, 15–18 February 2010; pp. 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Al-Haija, Q.; Al-Saraireh, J. Asymmetric Identification Model for Human-Robot Contacts via Supervised Learning. Symmetry 2022, 14, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatnawi, A.S.; Jaradat, A.; Yaseen, T.B.; Taqieddin, E.; Al-Ayyoub, M.; Mustafa, D. An Android Malware Detection Leveraging Machine Learning. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 1830201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Xu, S.; Xu, G.; Zhang, M.; Sun, D.; Liu, H. A Review of Android Malware Detection Approaches Based on Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 124579–124607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkifli, A.; Hamid, I.R.A.; Shah, W.M.; Abdullah, Z. Android Malware Detection Based on Network Traffic Using Decision Tree Algorithm. In Recent Advances on Soft Computing and Data Mining, Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Soft Computing and Data Mining (SCDM 2018), Johor, Malaysia, 6–7 February 2018; Ghazali, R., Deris, M., Nawi, N., Abawajy, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Al-Haija, Q.; Odeh, A.; Qattous, H. PDF Malware Detection Based on Optimizable Decision Trees. Electronics 2022, 11, 3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amro, A.; Al-Akhras, M.; Hindi, K.E.; Habib, M.; Shawar, B.A. Instance reduction for avoiding overfitting in decision trees. J. Intell. Syst. 2021, 30, 438–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, W.; Salleh, M.; Omar, A. A comparative study of Reduced Error Pruning method in decision tree algorithms. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Control System, Computing and Engineering, Penang, Malaysia, 23–25 November 2012; pp. 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierazzi, F.; Mezzour, G.; Han, Q.; Colajanni, M.; Subrahmanian, V.S. A data-driven characterization of modern Android spyware. ACM Trans. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2020, 11, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gana, N.N.; Abdulhamid, S.M.; Misra, S.; Garg, L.; Ayeni, F.; Azeta, A. Optimization of Support Vector Machine for Classification of Spyware Using Symbiotic Organism Search for Features Selection. In Information Systems and Management Science. ISMS 2020; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qabalin, M.K.; Naser, M.; Alkasassbeh, M. Android Spyware Detection Using Machine Learning: A Novel Dataset. Sensors 2022, 22, 5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlJarrah, M.N.; Yaseen, Q.M.; Mustafa, A.M. A Context-Aware Android Malware Detection Approach Using Machine Learning. Information 2022, 13, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshamrani, S. Design and Analysis of Machine Learning Based Technique for Malware Identification and Classification of Portable Document Format Files. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2022, 2022, 7611741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, S.V. Spyware Detection and Prevention using Deep Learning, A.I. for user applications. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2019, 7, 345–349. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Al-Haija, Q.; Krichen, M. A Lightweight In-Vehicle Alcohol Detection Using Smart Sensing and Supervised Learning. Computers 2022, 11, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, S.; Bobrovnikova, K.; Popov, P.T.; Kharchenko, V.; Medzatyi, D. Spyware detection technique based on reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Intelligent Information Technologies & Systems of Information Security, Khmelnytskyi, Ukraine, 10–12 June 2020; Volume 2623, pp. 307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Anumula, K.; Raymond, J. Adware, and Spyware Detection Using Classification and Association. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Deep Learning, Computing and Intelligence, Chennai, India, 7–8 January 2021; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 355–361. [Google Scholar]

- Fasano, F.; Martinelli, F.; Mercaldo, F.; Nardone, V.; Santone, A. Spyware Detection using Temporal Logic. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy, Prague, Czech Republic, 23–25 February 2019; Volume 1, pp. 690–699. [Google Scholar]

- Elmalaki, S.; Ho, B.J.; Alzantot, M.; Shoukry, Y.; Srivastava, M. Spycon: Adaptation based spyware in human-in-the-loop IoT. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops, San Francisco, CA, USA, 23 May 2019; pp. 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Suruthi, B.; Yuvasri, G.; Reena, R.; Kapilavani, R.K. Efficient handwritten passwords to overcome spyware attacks. Sci. Technol. 2021, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Al-Haija, Q.; Smadi, A.A.; Allehyani, M.F. Meticulously Intelligent Identification System for Smart Grid Network Stability to Optimize Risk Management. Energies 2021, 14, 6935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Al-Haija, Q.; Al Badawi, A. High-performance intrusion detection system for networked UAVs via deep learning. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 10885–10900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.; Rigoni, G.; Toffalini, F. ASAINT: A spy App identification system based on network traffic. In Proceedings of the ARES ’20—The 15th International Conference on Availability, Reliability, and Security, Virtual, 25–28 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, J.; Kaushal, R. CREDROID: Android malware detection by network traffic analysis. In Proceedings of the PAMCO 2016—2nd MobiHoc International Workshop on Privacy-Aware Mobile Computing, Paderborn, Germany, 5–8 July 2016; pp. 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Al-Haija, Q.; Al-Dala’ien, M. ELBA-IoT: An Ensemble Learning Model for Botnet Attack Detection in IoT Networks. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2022, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albulayhi, K.; Abu Al-Haija, Q.; Alsuhibany, S.A.; Jillepalli, A.A.; Ashrafuzzaman, M.; Sheldon, F.T. IoT Intrusion Detection Using Machine Learning with a Novel High Performing Feature Selection Method. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Al-Haija, Q.; Zein-Sabatto, S. An Efficient Deep-Learning-Based Detection and Classification System for Cyber-Attacks in IoT Communication Networks. Electronics 2020, 9, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.; Rashid, J.; Nisar, M.W. Android fragmentation classification, causes, problems and solutions. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Secur. 2016, 14, 992. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).