Attitudes toward Fashion Influencers as a Mediator of Purchase Intention

Abstract

:1. Introduction

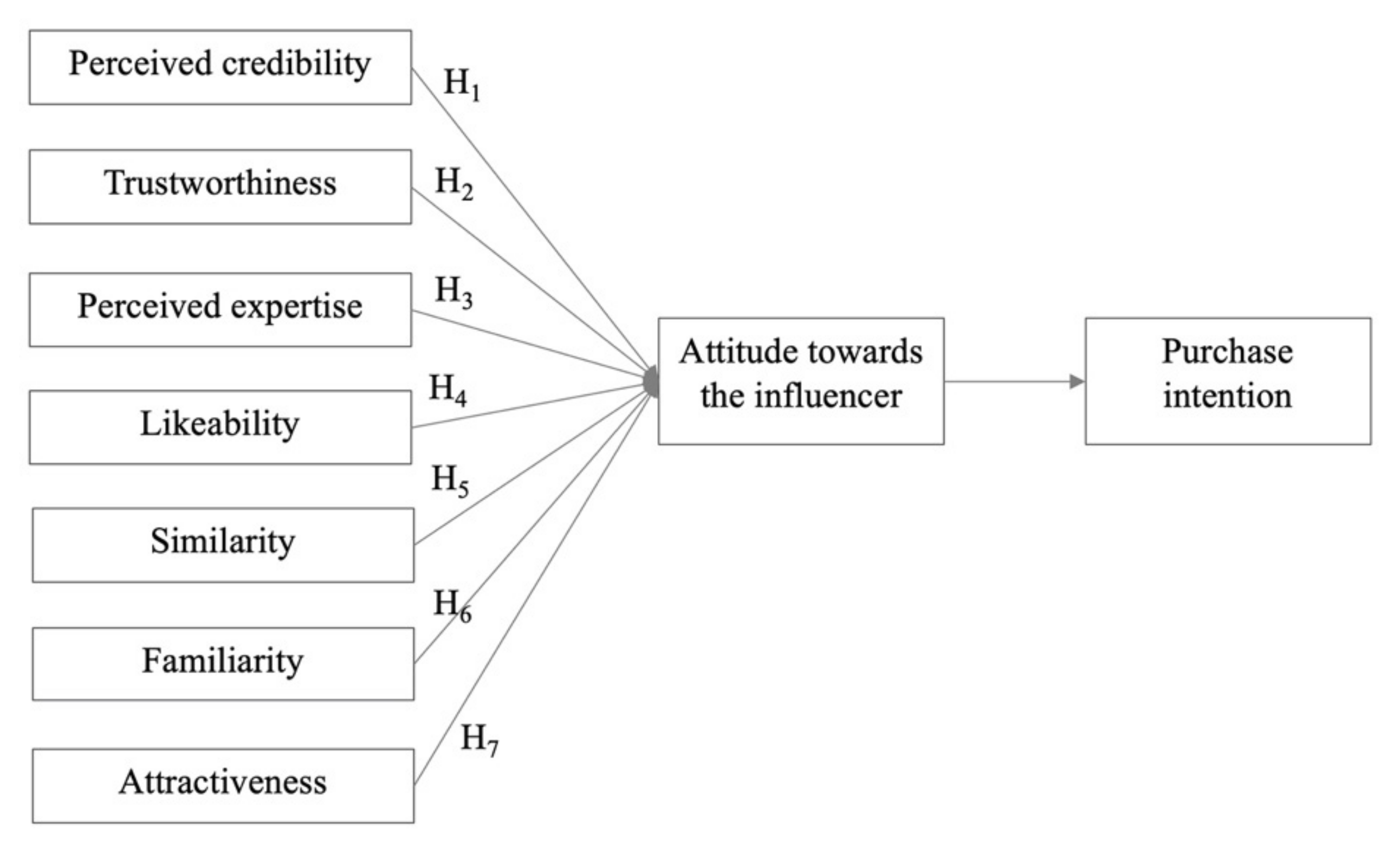

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Fashion Influencers

2.2. Purchase Intention and Attitude toward the Influencer

2.3. Perceived Credibility

2.4. Trustworthiness

2.5. Perceived Expertise

2.6. Likeability

2.7. Similarity

2.8. Familiarity

2.9. Attractiveness

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. The Sample

4.2. Frequencies

4.3. Differences

4.4. Correlations

4.5. Multiple Regression Analysis

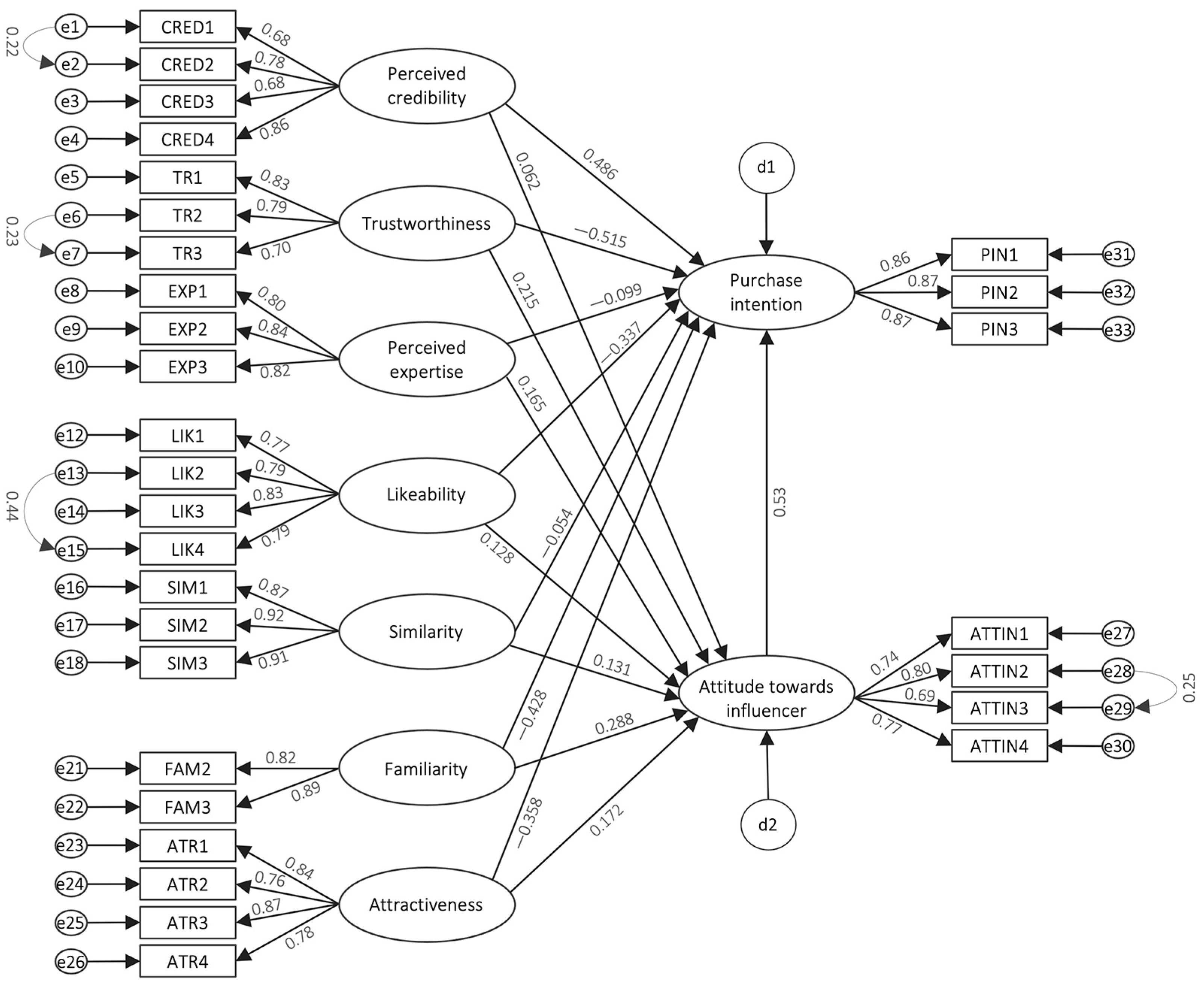

4.6. Path Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harari, Y.N. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind; Harvill Secker: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chetioui, Y.; Benlafqih, H.; Lebdaoui, H. How fashion influencers contribute to consumers’ purchase intention. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 24, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K.; Kefi, H. Instagram and YouTube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial interaction influence purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkan, I.; Evans, C. Social media or shopping websites? The influence of eWOM on consumers’ online purchase intentions. J. Mark. Commun. 2016, 24, 617–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Jianqiu, Z.; Dukhaykh, S.; Fan, M.; Trunk, A. Understanding the effects of eWOM antecedents on online purchase intention in China. Information 2021, 12, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehpour, M.; Wong, W.-K.; Van Pham, K.; Aulia, C.K. Repurchase intention of Korean beauty products among Taiwanese consumers. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2017, 29, 569–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehpour, M.; Dadvari, A.; Nugroho, W.; Do, B.-R. The dynamic stimulus of social media marketing on purchase intention of Indonesian airline products and services. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 33, 561–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehpour, M.; Ismail, T.; Purba, B.; Wong, W.-K. What makes GO-JEK go in Indonesia? The influences of social media marketing activities on purchase intention. J. Theor. Appl. Electr. Commer. Res. 2021, 17, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Armstrong, C.M.J. Collaborative consumption: The influence of fashion leadership, need for uniqueness, and materialism on female consumers’ adoption of clothing renting and swapping. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 13, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadwal, S.S.; Jamal, A.; Harris, T.; Brown, G.; Raudhah, S. Technology and sharing economy-based business models for marketing to connected consumers. In Handbook of Research on Innovations in Technology and Marketing for the Connected Consumer; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 62–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.A.; Sheth, J.N. A theory of buyer behavior. In Marketing: Critical Perspectives on Business and Management; Baker, M.J., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2001; Volume 3, pp. 81–105. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, S.; Rashidin, M.S.; Xiao, Y. Investigating the impact of digital influencers on consumer decision-making and content outreach: Using dual AISAS model. Econ. Res.—Ekon. Istraživanja 2021, 34, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, X.J.; Radzol, A.; Cheah, J.; Wong, M.W. The impact of social media influencers on purchase intention and the mediation effect of customer attitude. Asian J. Bus. Res. 2017, 7, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taillon, B.J.; Mueller, S.M.; Kowalczyk, C.M.; Jones, D.N. Understanding the relationships between social media influencers and their followers: The moderating role of closeness. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 29, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, M.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Building influencers’ credibility on Instagram: Effects on followers’ attitudes and behavioral responses toward the influencer. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, G. Perceived credibility of Chinese social media: Toward an integrated approach. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2018, 30, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.I.; Janis, I.L.; Kelley, H.H. Communication and Persuasion; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Hovland, C.I.; Weiss, W. The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opin. Q. 1951, 15, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munnukka, J.; Uusitalo, O.; Toivonen, H. Credibility of a peer endorser and advertising effectiveness. J. Consum. Mark. 2016, 33, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer Marketing: How Message Value and Credibility Affect Consumer Trust of Branded Content on Social Media. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, D.; Mustățea, M. Users’ perspective on the credibility of social media influencers in Romania and Germany. Rom. J. Commun. Public Relat. 2019, 21, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cialdini, R.B. Harnessing the Science of Persuasion. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2001, 284, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez-Sánchez, S.; Flavián, M.; Casaló, L.V.; Belanche, D. Influencers and brands successful collaborations: A mutual reinforcement to promote products and services on social media. J. Mark. Commun. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, Y.A.; Muqaddam, A.; Miller, S. The effects of the visual presentation of an Influencer’s Extroversion on perceived credibility and purchase intentions—Moderated by personality matching with the audience. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B. Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion; HarperCollins Publishers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Reinikainen, H.; Munnukka, J.; Maity, D.; Luoma-aho, V. ‘You really are a great big sister’—Parasocial relationships, credibility, and the moderating role of audience comments in influencer marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 36, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.-C.; Wu, L.-W.; Chang, Y.-Y.-C.; Hong, R.-H. Influencers on social media as References: Understanding the Importance of Parasocial Relationships. Sustainability 2021, 13, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, Y. Luxury haul video creators’ nonverbal communication and viewer intention to subscribe on YouTube. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2021, 49, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhanu, K.; Raj, S. The trustworthiness of travel and tourism information sources of social media: Perspectives of international tourists visiting Ethiopia. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyahya, M. The marketing influencers altering the purchase intentions of Saudi consumers: The effect of sociocultural perspective. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 24, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawack, R.E.; Bonhoure, E. Influencer is the New Recommender: Insights for Enhancing Social Recommender Systems. In Proceedings of the Conference on e-Business, e-Services and e-Society, Galway, Ireland, 1–3 September 2021; pp. 681–691. [Google Scholar]

- Koay, K.Y.; Cheung, M.L.; Soh, P.C.-H.; Teoh, C.W. Social media influencer marketing: The moderating role of materialism. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2021, 34, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, H.; Han, S.H.; Lee, J. Impacts of influencer attributes on purchase intentions in social media influencer marketing: Mediating roles of characterizations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderer, B.; Matthes, J.; Schäfer, S. Effects of disclosing ads on Instagram: The moderating impact of similarity to the influencer. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 40, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saima; Khan, M.A. Effect of social media influencer marketing on consumers’ purchase intention and the mediating role of credibility. J. Promot. Manag. 2020, 27, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, T.; Deraman, S.N.S.; Zainuddin, S.A.; Azmi, N.F.; Abdullah, S.S.; Anuar, N.I.M.; Mohamad, S.R.; Hashim, N.; Amri, N.A.; Abdullah, A.-R. Impact of Social Media Influencer on Instagram User Purchase Intention towards the Fashion Products: The Perspectives of UMK Pengkalan Chepa Campus Students. Eur. J. Mol. Clin. Med. 2020, 7, 2589–2598. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, M.A.; Marques, S.; Dias, Á. The impact of digital influencers’ characteristics on purchase intention of fashion products. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarage, H.P.; Ratnayake, G. Impact of Celebrity Endorsement through Social Media on Consumer Purchasing Intentions in Sri Lankan Fashion Industry. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Rome, Italy, 2–5 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedmann, K.-P.; von Mettenheim, W. Attractiveness, trustworthiness and expertise—Social influencers’ winning formula? J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 30, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, S.K.; Cacciatore, M.A.; Su, L.Y.-F.; McKasy, M.; O’Neill, L. Following science on social media: The effects of humor and source likability. Public Underst. Sci. 2021, 30, 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, B.; Choudhury, M.M.; Melewar, T.C. An integrated model of firms’ brand likeability: Antecedents and consequences. J. Strateg. Mark. 2015, 23, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reysen, S. Construction of a new scale: The Reysen likability scale. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2005, 33, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heerden, D.; Wiese, M. Why do consumers engage in online brand communities—And why should brands care? J. Consum. Mark. 2021, 38, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Veirman, M.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L. Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 798–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torres, P.; Augusto, M.; Matos, M. Antecedents and outcomes of digital influencer endorsement: An exploratory study. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyal, K.; Rubin, A.M. Viewer aggression and homophily, identification, and parasocial relationships with television characters. J. Broadcasting Electron. Media 2003, 47, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, A.P.; Janssen, L.; Verspaget, M. Celebrity vs. Influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility, and Product-Endorser fit. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Yan, Q.; Feng, G.C. Who will attract you? Similarity effect among users on online purchase intention of movie tickets in the social shopping context. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 40, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, G.; Ko, D.; Siu Yin, V.Y. Online word of mouth and consumer purchase intentions. Int. J. Advert. 2010, 29, 687–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, J.W.; Hutchinson, J.W. Dimensions of consumer expertise. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 13, 411–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martensen, A.; Brockenhuus-Schack, S.; Zahid, A.L. How citizen influencers persuade their followers. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2018, 22, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, R.; Nair, P.B. Social Media Influencers and Electronic Word of Mouth: The Communication Impact on Restaurant Patronizing. J. Content Community Commun. 2021, 14, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräve, J.-F. Exploring the perception of influencers vs Traditional celebrities: Are social media stars a new type of endorser? In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Social Media & Society, Toronto, ON, Canada, 28–30 July 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- McClure, C.; Seock, Y.-K. The role of involvement: Investigating the effect of brand’s social media pages on consumer purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satria, A.D.; Jatipuri, S.; Hartanti, A.D.; Sanny, L. The impact of celebrity endorsement by social influencer Celebgram on purchase intention of generation Z in fashion industry. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2019, 8, 397–404. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, F.F.Y. The Perceptions of Brand Co-appearance in Product Placement: An Abstract. In From Micro to Macro: Dealing with Uncertainties in the Global Marketplace. Proceedings of the AMSAC 2020. Academy of Marketing Science Annual Conference; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 217–218. [Google Scholar]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlFarraj, O.; Alalwan, A.A.; Obeidat, Z.M.; Baabdullah, A.; Aldmour, R.; Al-Haddad, S. Examining the impact of influencers’ credibility dimensions: Attractiveness, trustworthiness and expertise on the purchase intention in the aesthetic dermatology industry. Rev. Int. Bus. Strategy 2021, 31, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.T.; Huang, Y.Y.; Minghua, J. Relations among attractiveness of endorsers, match-up, and purchase intention in sport marketing in China. J. Consum. Mark. 2007, 24, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, C.S.; Lim, W.M.; Tan, R.W.; Teh, E.W. Impact of Social Media Influencer on Instagram User Purchase Intention: The Fashion Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, University Tunku Abdul Rahman, Kampar, Malaysia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, C.; Kim, H.K. Fancying the New Rich and Famous? Explicating the Roles of Influencer Content, Credibility, and Parental Mediation in Adolescents’ Parasocial Relationship, Materialism, and Purchase Intentions. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbuckle, J.L. Amos, Version 27.0; IBM SPSS: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-H.; Song, H. The influence of perceived credibility on purchase intention via competence and authenticity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | N | % Total | Cumulative % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 362 | 72.3 | 72.3 |

| Male | 139 | 27.7 | 100.0 | |

| Age | M ± SD; Min–Max | 21.1 ± 2.32; 15–25 | ||

| Education level | Basic education | 14 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| Secondary education | 289 | 57.7 | 60.5 | |

| Higher education | 198 | 39.5 | 100.0 | |

| Occupation | Inactive | 55 | 11.0 | 11.0 |

| Active | 446 | 89.0 | 100.0 |

| Items and Scales | M | SD | Sk (0.109) | Krt (0.218) | α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived credibility Item 1 | I do believe that fashion influencers I follow are convincing | 3.60 | 0.83 | −0.863 | 1.261 | |

| Perceived credibility Item 2 | I do believe that fashion influencers I follow are credible | 3.28 | 0.87 | −0.269 | −0.109 | |

| Perceived credibility Item 3 | I do believe that fashion influencers advertising is a good reference for purchasing products | 3.67 | 0.99 | −0.783 | 0.241 | |

| Perceived credibility Item 4 | I find purchasing product/service advertised by fashion Influencers I follow to be worthwhile | 3.35 | 0.93 | −0.479 | 0.099 | |

| Perceived credibility Total | 3.48 | 0.75 | −0.651 | 0.984 | 0.85 | |

| Trustworthiness Item 1 | I do believe that I can depend on fashion influencers I follow to make purchasing decisions | 3.26 | 1.03 | −0.496 | −0.439 | |

| Trustworthiness Item 2 | I do believe that fashion influencers I follow are sincere | 3.41 | 0.93 | −0.540 | 0.222 | |

| Trustworthiness Item 3 | I do believe that fashion influencers I follow use the same products they advertise | 3.22 | 1.01 | −0.242 | −0.603 | |

| Trustworthiness Total | 3.29 | 0.85 | −0.332 | −0.067 | 0.83 | |

| Perceived expertise Item 1 | The fashion influencers I am following are experts in their field | 3.13 | 0.99 | −0.195 | −0.287 | |

| Perceived expertise Item 2 | The fashion influencers I am following have great knowledge | 3.29 | 0.94 | −0.377 | −0.063 | |

| Perceived expertise Item 3 | The fashion influencers I am following are experienced in their field | 3.41 | 0.90 | −0.564 | 0.197 | |

| Perceived expertise Total | 3.27 | 0.83 | −0.363 | 0.308 | 0.86 | |

| Likeability Item 1 | The fashion influencers I follow are warm persons | 3.57 | 0.80 | −0.588 | 1.056 | |

| Likeability Item 2 | The fashion influencers I follow are likeable persons | 3.82 | 0.77 | −0.890 | 2.156 | |

| Likeability Item 3 | The fashion influencers I follow are sincere persons | 3.47 | 0.80 | −0.352 | 0.827 | |

| Likeability Item 4 | The fashion influencers I follow are friendly persons | 3.73 | 0.78 | −0.733 | 1.663 | |

| Likeability Total | 3.65 | 0.68 | −0.837 | 2.521 | 0.89 | |

| Similarity Item 1 | I am similar to the fashion influencers I follow on overall lifestyle | 2.74 | 1.14 | 0.170 | −0.885 | |

| Similarity Item 2 | I have a lot in common with the influencers I follow | 2.86 | 1.09 | 0.056 | −0.736 | |

| Similarity Item 3 | I am a lot alike the influencers I follow | 2.75 | 1.07 | 0.132 | −0.797 | |

| Similarity Total | 2.79 | 1.03 | 0.126 | −0.694 | 0.93 | |

| Familiarity Item 2 | I have knowledge about the fashion influencers I follow. | 3.41 | 0.97 | −0.861 | 0.321 | |

| Familiarity Item 3 | I easily recognize the fashion influencers I follow | 3.63 | 0.98 | −1.080 | 0.907 | |

| Familiarity Total | 3.52 | 0.91 | −1.042 | 1.025 | 0.84 | |

| Attractiveness Item 1 | The fashion followers I follow are very attractive | 3.55 | 0.83 | −0.661 | 1.130 | |

| Attractiveness Item 2 | The fashion followers I follow are very stylish | 3.76 | 0.83 | −1.054 | 2.049 | |

| Attractiveness Item 3 | The fashion followers I follow are good looking | 3.70 | 0.82 | −0.891 | 1.633 | |

| Attractiveness Item 4 | The fashion followers I follow are sexy | 3.49 | 0.85 | −0.516 | 0.788 | |

| Attractiveness Total | 3.63 | 0.72 | −0.906 | 2.631 | 0.89 | |

| Attitude toward influencer Item 1 | I do believe that fashion influencers serve as fashion models for me | 3.13 | 1.08 | −0.351 | −0.632 | |

| Attitude toward influencer Item 2 | I do believe that fashion influencers present interesting content | 3.65 | 0.88 | −0.923 | 1.180 | |

| Attitude toward influencer Item 3 | I do believe that fashion influencers provide new deals about different products and services | 3.65 | 0.85 | −1.010 | 1.487 | |

| Attitude toward influencer Item 4 | I do consider fashion influencers as a reliable source of information and discovery | 3.28 | 0.98 | −0.445 | −0.166 | |

| Attitude toward influencer Total | 3.39 | 0.64 | −0.580 | 1.760 | 0.84 | |

| Purchase intention Item 1 | I most frequently have intentions to purchase products advertised by the fashion influencers I follow | 3.05 | 1.10 | −0.218 | −0.821 | |

| Purchase intention Item 2 | I generally recommend products and/or services advertised by the fashion influencers I follow | 3.07 | 1.09 | −0.242 | −0.744 | |

| Purchase intention Item 3 | I will buy the fashion item advertised by fashion influencers in the future | 3.20 | 1.04 | −0.402 | −0.346 | |

| Purchase intention Total | 3.10 | 0.98 | −0.314 | −0.454 | 0.90 |

| Variables | Gender | N | M | SD | t | df | p Value | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived credibility Total | Male | 139 | 3.31 | 0.08 | −2.679 | 200.844 | 0.008 | 0.75 |

| Female | 362 | 3.54 | 0.04 | |||||

| Trustworthiness Total | Male | 139 | 3.14 | 0.08 | −2.529 | 499 | 0.012 | 0.85 |

| Female | 362 | 3.35 | 0.04 | |||||

| Perceived expertise Total | Male | 139 | 3.24 | 0.08 | −0.573 | 499 | 0.567 | 0.83 |

| Female | 362 | 3.29 | 0.04 | |||||

| Likeability Total | Male | 139 | 3.54 | 0.07 | −1.938 | 204.07 | 0.054 | 0.68 |

| Female | 362 | 3.69 | 0.03 | |||||

| Similarity Total | Male | 139 | 2.87 | 0.09 | 1.12 | 499 | 0.263 | 0.11 |

| Female | 362 | 2.75 | 0.05 | |||||

| Familiarity Total | Male | 139 | 3.26 | 0.09 | −3.621 | 208.935 | <0.001 | 0.89 |

| Female | 362 | 3.62 | 0.04 | |||||

| Attractiveness Total | Male | 139 | 3.55 | 0.07 | −1.269 | 200.12 | 0.206 | 0.72 |

| Female | 362 | 3.66 | 0.03 | |||||

| Attitude toward influencer Total | Male | 139 | 3.29 | 0.07 | −1.954 | 198.274 | 0.052 | 0.64 |

| Female | 362 | 3.43 | 0.03 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Perceived credibility | 1 | ||||||||

| 2 Trustworthiness | 0.768 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 3 Perceived expertise | 0.587 ** | 0.629 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 4 Likeability | 0.657 ** | 0.690 ** | 0.627 ** | 1 | |||||

| 5 Similarity | 0.533 ** | 0.542 ** | 0.530 ** | 0.496 ** | 1 | ||||

| 6 Familiarity | 0.563 ** | 0.561 ** | 0.509 ** | 0.619 ** | 0.504 ** | 1 | |||

| 7 Attractiveness | 0.503 ** | 0.450 ** | 0.461 ** | 0.587 ** | 0.386 ** | 0.546 ** | 1 | ||

| 8 Attitude toward the influencer | 0.834 ** | 0.830 ** | 0.770 ** | 0.838 ** | 0.749 ** | 0.771 ** | 0.708 ** | 1 | |

| 9 Purchase intention | 0.663 ** | 0.653 ** | 0.596 ** | 0.557 ** | 0.594 ** | 0.543 ** | 0.438 ** | 0.733 ** | 1 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | |

| Perceived credibility | 0.244 * | 0.123 | 0.255 * | 0.124 |

| Trustworthiness | 0.174 * | 0.096 | 0.177 * | 0.096 |

| Perceived expertise | 0.162 * | 0.087 | 0.159 * | 0.088 |

| Likeability | −0.041 | 0.128 | −0.042 | 0.129 |

| Similarity | 0.213 * | 0.100 | 0.210 * | 0.102 |

| Familiarity | 0.097 | 0.086 | 0.103 | 0.087 |

| Attractiveness | 0.018 | 0.115 | 0.018 | 0.116 |

| Attitude toward influencers | 0.048 | 0.629 | 0.039 | 0.636 |

| Gender | −0.041 | 0.068 | ||

| Age | −0.018 | 0.013 | ||

| Education | −0.025 | 0.057 | ||

| Occupation | 0.009 | 0.094 | ||

| F(df, p value) | 81.954 (8, <0.001) | 54.767 (12, <0.001) | ||

| Hypothesis | Paths | Statement of the Hypothesis | Indirect | Direct | Total | Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PC→AtI→PI | Attitude toward influencers mediates the relationship between perceived credibility and purchase intention. | 0.119 * | 0.062 (NS) | 0.605 *** | Supported |

| H2 | TW→AtI→PI | Attitude toward influencers mediates the relationship between trustworthiness and purchase intention. | 0.415 *** | 0.215 (NS) | 0.100 * | Supported |

| H3 | PE→AtI→PI | Attitude toward influencers mediates the relationship between perceived expertise and purchase intention. | 0.318 *** | 0.165 (NS) | 0.219 ** | Supported |

| H4 | L→AtI→PI | Attitude toward influencers mediates the relationship between likeability and purchase intention. | 0.248 ** | 0.128 (NS) | 0.089 (NS) | Not supported |

| H5 | S→AtI→PI | Attitude toward influencers mediates the relationship between similarity and purchase intention. | 0.253 ** | 0.131 (NS) | 0.198 * | Supported |

| H6 | F→AtI→PI | Attitude toward influencers mediates the relationship between familiarity and purchase intention. | 0.555 *** | 0.288 ** | 0.127 * | Supported |

| H7 | A→AtI→PI | Attitude toward influencers mediates the relationship between attractiveness and purchase intention. | 0.331 *** | 0.172 (NS) | 0.027 (NS) | Not supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magano, J.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M.; Walter, C.E.; Leite, Â. Attitudes toward Fashion Influencers as a Mediator of Purchase Intention. Information 2022, 13, 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13060297

Magano J, Au-Yong-Oliveira M, Walter CE, Leite Â. Attitudes toward Fashion Influencers as a Mediator of Purchase Intention. Information. 2022; 13(6):297. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13060297

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagano, José, Manuel Au-Yong-Oliveira, Cicero Eduardo Walter, and Ângela Leite. 2022. "Attitudes toward Fashion Influencers as a Mediator of Purchase Intention" Information 13, no. 6: 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13060297

APA StyleMagano, J., Au-Yong-Oliveira, M., Walter, C. E., & Leite, Â. (2022). Attitudes toward Fashion Influencers as a Mediator of Purchase Intention. Information, 13(6), 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13060297