Abstract

Interaction is the main feature of social media, while in recent years, frequent privacy disclosure events of the social media user affect users’ privacy disclosure behavior. In this paper, we explore the mechanism of interaction characteristics by social media apps on users’ privacy disclosure behavior. Using SOR theoretical models and the privacy calculus theory, the effects of privacy disclosures on TikTok are examined. Structural equation modeling is used to analyze the data from 326 questionnaires. We concluded that human–computer interaction (perceived personalization, perceived control) and interpersonal interaction (perceived similarity) positively and negatively affected perceived benefits and perceived risks, respectively, and had positive effects on intention to disclose privacy through perceived benefits and perceived risks, respectively, except that perceived personalization had no effect on perceived risk and intention to disclose privacy. In addition, perceived benefits and perceived risks played an intermediary role in interactivity and privacy disclosure intention. Finally, we provided countermeasures and suggestions for social media operators and policy makers.

1. Introduction

In recent years, information and Internet technology has developed so rapidly that social media has steadily entered public life, making people’s communication and communication more convenient. People can obtain and release information anytime and anywhere through social media of the open and interactive communication platform [1]. In recent years, the social media industry has developed vigorously. For example, Douyin has become a leader in the global social media industry with 800 million active users and more than 2 billion downloads per month, providing services in 150 countries [2]. The growing popularity of social media has greatly increased the importance of online social interaction. However, the problem of user privacy disclosure comes along. For example, 87 million Facebook users’ information was stolen in 2018 [3]; the TikTok app of short video sharing on social media lacks private data security [4]; and according to the 49th Statistical Report on Internet Development in China, as of December 2021, 22.1% of Internet users suffered from personal information leakage, which is the highest proportion of privacy leakage problems. In the case of frequent data leakage events, most consumers are worried about their online privacy [5], many of them believe that they have no effective means to protect their personal information disclosed on the Internet [6] and even give up the privacy information protection strategy, so they are reluctant to disclose personal privacy. However, the lower the users’ intention to disclose privacy, the lower the vigor of social media, so that the commercial value of the platform is decreased, which is not conducive to the sustainable development of social media. Therefore, understanding users’ intention to disclose privacy is an indispensable part of the sustainable development of social media platforms. How to maintain the intention of social media users to disclose their privacy has become an urgent problem for social media service providers. At the same time, maintaining users’ reasonable right of privacy disclosure is also an important part of building a harmonious network environment.

Quite a few scholars have conducted a large number of studies about the interfering factors of privacy disclosure intention. Some scholars suggest that privacy calculus in terms of privacy disclosure will play an important role. The privacy calculus, first propounded by Laufer and Wolfe in 1977, is one of the core classical theories of privacy behavior research [7]. Chen [8] treats the privacy calculus as a kind of rational factor, he believes that the privacy disclosure behavior of users on a social media platform is a rational exchange behavior, when the benefits of using social media outweigh the detectable privacy risks, people tend to post their information on social networking sites, and vice versa. Sun et al. [9] explored utilitarian benefits and entertainment benefits on the basis of perceived benefits, further expanding the privacy calculus model. Dienlin and Metzger [10] believe that there are potential risks in forming connections on SNS, that is, privacy information may be misinterpreted or misused by other industries or users, thus affecting the self-withdrawal reaction of privacy disclosure and expanding the theoretical framework of privacy calculus. In their studies, perceived benefits and perceived risks are considered to be important factors in predicting intention to disclose privacy.

Since interactivity is a key feature of social media, Jiang et al. [11] observed that even though users realize the risks involved in synchronous online social interactions, the users still disclose their abundant personal information. Additionally, they find that the perception of anonymity, media richness, and intrusiveness in online social interactions will affect users’ privacy trade-off, thus affecting privacy disclosure. Subsequently, some scholars believe that interaction plays a significant role in determining users’ manners and behaviors, the relationships show positive or inverted U-shaped and the main influencing factors include perceived personalization and perceived control [12,13]. Kang and Namkung [14] revealed that perceived personalization has positive effects on perceived benefits and perceived risks involved in privacy disclosure. Princi and Kramer [15] believed that when users perceive control, they will see less risks and more gains, thus increasing their intention to disclose privacy. In addition, some scholars have proposed that perceived similarity in interpersonal interaction has an indirect positive impact on users’ behavioral intention in the social network context [16,17]. There are many studies on the influence of interaction on user behavior, but a very small number of them have considered the effect of interactivity on privacy disclosure intention under the effect of privacy calculus. Through frequent interaction on social media platforms, users can establish close social network connections, so as to weigh the perceived benefits and risks after interaction and make privacy disclosure decisions. Based on this, from the perspective of interaction, this paper draws on the SOR theory model and innovatively combines human–computer interaction and interpersonal interaction as external environmental stimuli, and takes privacy calculus as an internal organism to explore the influence mechanism of interaction under the intermediary effect of privacy calculus on social media users’ intention to disclose privacy.

The other contents of this article is arranged as below. First of all, a literature review is conducted on the topic. Then, as part of the theoretical background and research hypothesis, we review the related literature and propose our hypotheses. The section of research methods and results introduces our research methods and analysis in detail, and introduces our research results. At last, we discuss related research conclusions, meanings, suggestions, and limitations of this study, including thoughts for further research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Stimulus–Organism–Response Framework

The SOR model is one of the foundations of cognitive psychology. The SOR model believes that human complex behavior is divided into two parts: stimulation and response. Human behavior is the response to stimulation. It theoretically and concretely explains the effect of external environmental characteristics on an individual’s emotional cognitive response and subsequent behavior. Where S stands for external stimulation environment, O is the internal organism response, and R represents the corresponding response of the body after receiving the stimulus through certain inner activities, such as reasoning, attitude, emotion, and behavior [18].

The SOR model has been widely applied to study online user psychology and behavior to investigate how external environmental factors affect them [19]. This paper uses this model as the theoretical basis for studying social media users’ privacy disclosure behavior for two reasons. Firstly, this model has been used to research online user behavior before. Based on the SOR framework, Zhang et al. [20] studied the effects of three technological stimuli factors (perceived interactivity, personalization, and sociability) on users’ virtual experience and subsequent social business willingness. Liu et al. [16] investigated the influence of interpersonal interaction on consumers’ online experience, and then online purchase intention. Therefore, this framework seems to be suitable for the study of user privacy disclosure behavior intentions. Second, considering environmental factors play a significant role in influencing user behavior, the SOR paradigm supplies a brief and structured method to measure the influence of external environmental stimuli on users’ internal psychological elements, and then test the impact of users’ intention to disclose privacy. Therefore, we apply this model to user behavior, aiming to reflect how interactivity affects social media users’ intention of privacy disclosure behavior psychologically through privacy calculus.

2.2. Interactivity

The difference between social media and traditional media lies in the characteristic of interaction [21], which is generally believed to refer to the extent of interaction when different individuals communicate with each other [22]. In the study of social interaction, interaction is defined as a stimulus [23]. As an important social stimulus factor of social media, interactivity can stimulate users’ internal perception and ultimately produce behavioral intention response [16].

Interaction is a multi-faceted concept. Hoffman and Novak [24] believe that interaction can be divided into human–computer interaction and interpersonal interaction. In terms of human–computer interaction, perceptual interaction is a concept that is still developing and is generally considered to be a multi-component structure, which is made up of related but different elements, such as: no delay, real-time conversation, and an engaging aspect [25]; control, two-way communication, and time [26]. In addition, Wu and Wu [27] divided perceptual interaction into perceived control, perceived response, and perceived personalization. Although there are many aspects of perceived interactivity, the topic is explored from different perspectives by different researchers. We follow the opinion of Wu and Wu (2006), but this study involves the background of privacy disclosure in social media, and we think responsiveness is irrelevant to this study because it refers to the reaction speed of technical products or users [28]. In addition, we believe that the focus of interactivity is on the richness and control of the interaction between customers and social media platforms and between customers. Thus, we finally identify two aspects of interactivity: personalization and control, which represent the richness and degree of control of the interaction, respectively. Personalization reflects the degree to which information or services meet users’ unique needs; control represents users’ control over the information and content of scientific and technological products [28].

In terms of interpersonal interaction, with the development of the Internet, the traditional human–computer interaction between users and the system, which simply responds to the needs of users, can no longer meet the needs of users. Therefore, person-to-person interaction between users has become a new trend. Social media platforms need to promote membership interaction, and interacting frequently by membership will strengthen the interpersonal attraction of web platforms [29]. Liu et al. [16] mainly focus on three types of interpersonal interaction among users, including familiarity, professionalism, and similarity. Among them, similarity means psychological characteristics for self-perceived similar aspects (such as preference and taste) among social media members; professionalism reflects the knowledge and level of members in a certain field; familiarity refers to the degree of interaction between members and their understanding of other members on the platform [29]. This paper will adopt this classification to study interpersonal interaction; however, considering the study background of privacy disclosure in social media, we deem that professionalism and familiarity are irrelevant to this study.

2.3. Privacy Calculus Theory

The privacy calculus theory, first propounded by Laufer and Wolfe in 1977, is one of the core classical theories of privacy behavior research [7], which is formed on the basis of utility maximization theory in economics and social contract theory and social exchange theory in social psychology [11]. It emphasizes that individuals’ perception of privacy information is different according to the return they expect to get by disclosing their personal information [30,31]. In view of the trade-off analysis between costs and profits, privacy calculus theory interprets individuals’ privacy concern as an exchange of interests in certain aspects through releasing private information [32]. Studies have shown that individuals on the disclosure of personal information benefits and risks analysis, when individuals think that disclosure of overall revenue more than or at least the equivalent of perceived risk, they may be willing to disclose their privacy information [33], while any disclosure behavior means the loss of personal information, but provided that there is enough income under the affordable risk, individuals will tend to accept such losses [31]. In recent years, privacy calculus theory has been widely used to measure users’ inner psychological perception as the academic circles pay more attention to privacy issues. For example, according to the privacy calculus theory, Liu et al. [34] studied the influencing factors of online group-buying behavior by taking perceived benefit, perceived risk, and trust as measurement variables, respectively. In an empirical study, Pentina et al. [35] verified that users’ privacy concerns and perceived privacy benefits would influence behaviors through influencing privacy disclosure intentions. Therefore, we use the privacy calculus theory of perceived benefits and perceived risks to measure the internal psychological perception of social media users. Between them, perceived benefits in the context of this paper refer to the potential value that social media users think online interaction can bring to them. Perceived privacy risks in the background of this study refer to the potential loss of privacy that social media users think online interaction brings to them.

In the framework of SOR theory, organism response refers to the cognitive and affective process of individuals as well as their attitude or behavioral response after being stimulated by the external environment [18]. Cognitive response refers to the cognitive process of individuals when they are stimulated by environmental stimuli [36], while emotional response refers to the emotional response of individuals interacting with environmental stimuli [37]. Therefore, based on the above analysis, we introduce the perceived benefits and perceived risks in privacy calculus theory, and regard them as the organic factors of this study so as to further interpret the cognitive and emotional responses of users after interactive stimulation in the social media context.

2.4. Privacy Disclosure Intention

The theory of planned behavior holds that people’s behaviors are mainly affected by their behavioral intentions [38]. Previous studies have demonstrated that users’ intention to disclose privacy can reflect their behavioral results. Malhotra et al. [39] pointed out that the intention of privacy disclosure of Internet users has a positive impact on privacy disclosure behavior. Hajli and Lin [40] also found that sharing information intention on SNS has a positive correlation with users’ actual information disclosure.

The final part of the SOR model is response, which means the consequences of social interactions on social media and comes in the form of user privacy disclosure. Based on cognitive ability and emotional reactions, response stands for users’ final decision. Therefore, we treat privacy disclosure intention, especially in the context of social media, as the response factor. Our study is consistent with preceding research that takes the intention to privacy disclosure as a response factor by using the SOR model [41,42].

3. Research Models and Hypotheses

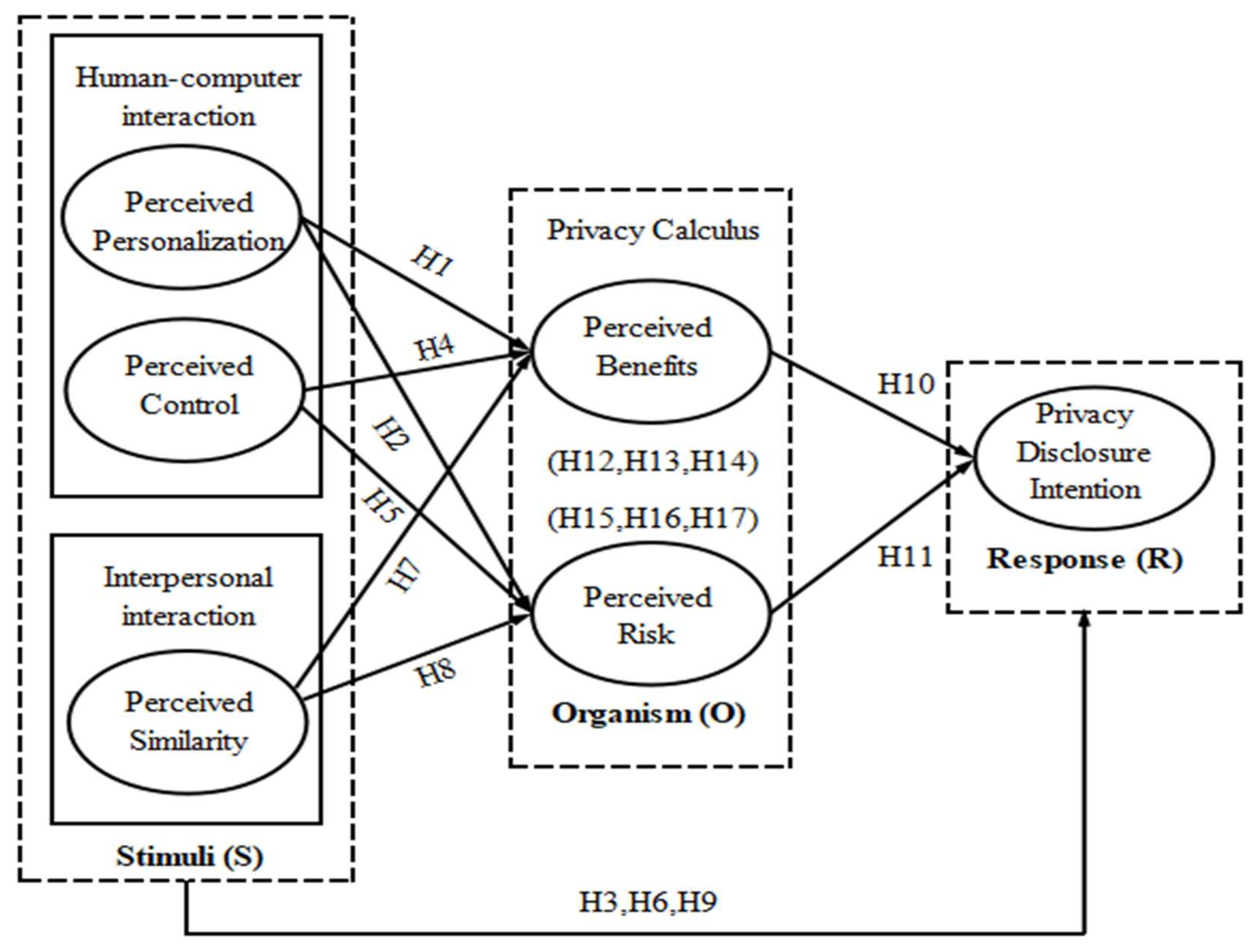

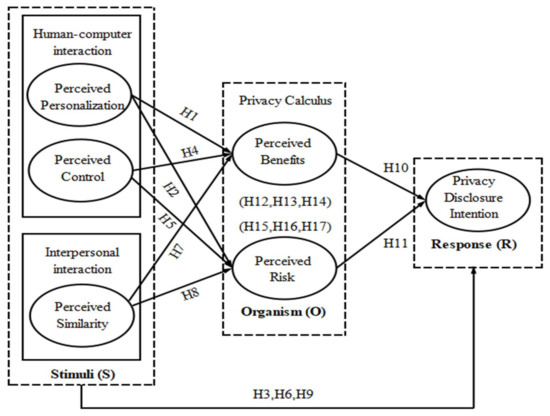

Our study aims to explore the influence mechanism of interactivity on users’ intention to disclose privacy from the perspective of privacy calculus. The research model is described in Figure 1, which reflects the impact of interactivity (i.e., perceived personalization, perceived control, and perceived similarity) on intention to disclose privacy, and the role of privacy calculus (i.e., perceived benefits and perceived risks). In this part, we will interpret the interrelationships among all variables in the research framework.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3.1. The Impact of Human–Computer Interaction (Perceived Personalization) on Privacy Calculus and Privacy Disclosure Intention

We believe that social interaction is a significant influence factor and a basic need for privacy calculus and privacy disclosure behavior intentions. After social media interaction, people will judge privacy issues according to their own perception. Perceived personalization refers to the perception that the information received by users conforms to their preferences [43]. Personalization facilitates users to reduce the search time of obtaining the accurate data and information [44], which expands users’ switching costs and satisfaction, leading to further use of social media [45]. Consequently, personalization is seen as a significant factor affecting the benefits of privacy exchange. If users find personalization valuable, users’ concerns about personalization may override privacy issues and cause the intentional disclosure of more private information. From the perspective of social exchange theory, consumers probably post their privacy information to interchange the personalized services or information they need [46].

However, personalized services are premised on the acquisition of large amounts of user data, and also impose a number of psychological costs on users, because customers’ personal data are required, such as location information [47], demographic data [48], or transaction information [49]. Disclosure of this data could lead to unwanted placement, price discrimination, and unauthorized access. Kang and Namkung [14] reveal that personalization has positive correlation with perceived risks and perceived benefits involved in privacy disclosure. Despite the added value of personalized services, privacy risks also come with them. Therefore, our hypotheses are proposed as follows:

H 1.

Perceived personalization (PP) has a positive effect on users’ perceived benefits (PB).

H 2.

Perceived personalization (PP) has a positive effect on users’ perceived risks (PR).

H 3.

Perceived personalization (PP) has a positive effect on users’ privacy disclosure intention (PDI).

3.2. The Impact of Human–Computer Interaction (Perceived Control) on Privacy Calculus and Privacy Disclosure Intention

A basic respect of privacy is how to control personal privacy information. Control represents the right to control users over their private information. Users should have the ability to freely control whether to disclose their privacy on social media, as well as dominate the visibility of their privacy information. Highly controlled users who know what types of private information to submit and how best to protect their privacy will substantially decrease their privacy concerns about using social media messaging services. In the process of social media privacy disclosure, if users perceive risks, they will reinforce the control of information, so as to avoid risks [50]. Therefore, when users perceive control, they will sense less risks and more gains [15]. In addition, users believe that the privacy boundary has a high level of security when they have a high degree of privacy control, so they will try to expand their privacy boundary and improve their intention to disclose privacy [51]. Cavusoglu et al. [52] studied the influence of the privacy statement about Facebook users’ intention to disclose information and find that when users have more privacy control rights, users are willing to disclose their privacy information. Therefore, we proposed the hypotheses as below:

H 4.

Perceived control (PC) has a positive effect on users’ perceived benefits (PB).

H 5.

Perceived control (PC) has a negative effect on users’ perceived risks (PR).

H 6.

Perceived control (PC) has a positive effect on users’ privacy disclosure intention (PDI).

3.3. The Effect of Interpersonal Interaction (Perceived Similarity) on Privacy Calculus and Privacy Disclosure Intention

Similarity, which can be defined as the proximity of demographic characteristics (such as gender and age) or the characteristics of psychology (such as lifestyle and personality), is considered to be the basis and social adhesive of interaction in the context of online media [53]. Similarity among users mainly represents common characteristics that can be observed, and communication becomes more and more beneficial if there are similarities between communication partners [54]. Al-natour et al. [55] proposed that the similarity of consumers’ perception of other members helps them enjoy interaction. People have a stronger sense of connection and intimacy with similar people [56] and receive more social support [54]. Needham and Vaske [57] believe that perceived similarity would lead to higher social trust and thus lower perception of risk. Moreover, Trepte et al. [17] found that users’ similarity would increase self-privacy disclosure through the use of privacy issues and social support expectations. Therefore, our hypotheses are suggested as follows:

Perceived control (PC) has a positive effect on users’ perceived benefits (PB).

H 7.

Perceived similarity (PS) has a positive effect on users’ perceived benefits (PB).

H 8.

Perceived similarity (PS) has a negative effect on users’ perceived risks (PR).

H 9.

Perceived similarity (PS) has a positive effect on users’ privacy disclosure intention (PDI).

3.4. The Effect of Privacy Calculus on Privacy Disclosure Intention

In view of the privacy calculus theory (PCT), assorted scholars have studied the relationship among perceived benefits, perceived risks, and privacy disclosure intentions. Perceived benefits are defined as the emotional, tool, information, and evaluation support that users obtain by disclosing personal privacy [58]. According to the PCT, users are inclined to disclose their personal information when the benefits of privacy outweigh its costs; otherwise, they tend to keep their information private. In the process of social media interaction, users’ perceived benefits mainly include utilitarian and hedonistic interests. Lin and Lu [59] pointed out that utilitarian and hedonistic interests would encourage users to use social networking sites. In addition, Teubner and Flath [60] proposed that the higher the perceived benefits, the more willing users are to disclose information, and vice versa. Princi and Kramer [15] demonstrated that perceived benefits have a significant positive effect on the actual use of electronic health devices. To sum up, when users feel the benefits brought by privacy disclosure, their intention and behavior to disclose privacy will be more positive.

Perceived risks refer to the possible loss caused by users’ personal information disclosure due to illegal behavior or improper use of information, and is the expectation of users for the worst result [39]. The risks perceived by users mainly come from the abuse of information and the illegal use of third-party organizations, such as the online tracking and recording of information, the dissemination of information on the Internet, and the selling of users’ personal information by third-party organizations. Xu et al. [61] proposed that perceived privacy risk has a negative correlation with privacy disclosure intention in the network environment. Yu et al. [62] proved that perceived privacy risk can significantly reduce the intention to disclose personal information by using the meta-analytic method. In other words, the greater the adverse impact or loss felt by users, the more negative their intention to disclose their privacy will be. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H 10.

Perceived benefits (PB) have a positive effect on users’ privacy disclosure intention (PDI).

H 11.

Perceived risks (PR) have a negative effect on users’ privacy disclosure intention (PDI).

3.5. Mediating Effect of Privacy Calculus

Privacy calculus is considered to be an important predictor of intention to disclose privacy. Jiang et al. [11] found that users seek immediate social emotion and satisfaction through online interaction, and privacy calculus can predict users’ privacy disclosure behavior in online social interaction. In addition, Kehr et al. [63] proposed that privacy calculus takes a completely mediating role between the impact of affective factors and information disclosure. Therefore, we can make assumptions that privacy calculus can become the intermediary among privacy disclosure intention and perceived personalization, perceived control, and perceived similarity. Based on this, the hypotheses are as follows:

H 12, H 13, H 14.

Perceived benefits mediate the effect of perceived personalization, perceived control, and perceived similarity on privacy disclosure intention, respectively.

H 15, H 16, H 17.

Perceived risks mediate the effect of perceived personalization, perceived control, and perceived similarity on privacy disclosure intention, respectively.

4. Research Design

4.1. Questionnaire Design

This paper adopted the method of the questionnaire survey. The questionnaire is composed of two parts: basic information and subject questionnaire. Basic information included gender, age, educational background, frequency, and duration of use, etc. It can not only observe the distribution of samples, ensure the universality and representativeness of data, but also facilitate the understanding of the basic characteristics of samples and user usage. The subjects used the five-level Likert scale, the number 1 stands for strongly disagree and the number 5 means strongly agree (details refer to Table A1). The projects to be measured referred to previous studies on users’ privacy disclosure intention and finally determined specific measurement variables. Three items of perceived personalization and four items of perceived control were referred to Lee et al. [12]. Four items of perceived similarity were referred to Liu et al. [16]. Four items of perceived benefits were referred to Khang et al. [64]. Four items of perceived risks were referred to Nemec Zlatolas et al. [65]. Four items of privacy disclosure intention were referred to Zhao et al. [66].

4.2. Data Collection

TikTok is an extremely popular social media platform among young people in the United States [67] and around the world [68], in particular, it is more popular among teenagers than other social media like Instagram, Snapchat, and Facebook [69]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, young people in lockdown turned to TikTok to pass the time, socialize, and share their daily experiences [70]. Therefore, under the circumstances of the normalization of the epidemic, users of Chinese social media TikTok were selected for this survey. We commissioned the professional wenjuanxing online survey service institution to collect data. We added the following question to the questionnaire: “Have you downloaded the TikTok APP?” In answer to this question, 22 respondents filled “no”. On account of our current study was concerning TikTok users’ privacy disclosure behavior, 22 respondents were excluded. Attention checks were also set, and we ended up with 326 valid questionnaires out of 374 original questionnaires. Table 1 showed that there were 151 male (46.3%) and 175 female (53.7%) interviewees in the collected samples, with an average gender ratio. At the age level, respondents aged 18 to 40 accounted for 68.4% of the total sample, and the respondents were mainly young users. In terms of educational level, 201 respondents (61.7%) had junior college or a Bachelor degree. At the level of frequency used, the majority of respondents used 1–2 h, accounting for 56.7% of the total sample. In terms of the length of use, 68.7% of respondents had used TikTok for 1–3 years.

Table 1.

Basic statistics of samples (n = 326).

4.3. Data Analysis

IBM SPSS 19 and AMOS 26.0 software (IBM, Beijing, China) were used to analyze the collected data, including descriptive statistical analysis, the reliability and validity test, and structural equation model (SEM) analysis. SEM is a method to establish, estimate, and test causality. It can replace multiple regression, path analysis, factor analysis, covariance analysis, and other methods to clearly analyze the role of individual indicators on the overall and the relationship between individual indicators. It is a multivariate statistical modeling technology mainly used in confirmatory model analysis.

4.3.1. Reliability and Validity Test

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) can evaluate the degree of fit of the test model according to all kinds of fitting indexes. In order to test the internal consistency reliability, convergence validity, and differential validity of the proposed structure model, CFA analysis was applied to six variables PP, PC, PS, PB, PR, and PDI (see Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

Measurement coefficient of research model.

Table 3.

Discriminatory validity of variables.

Cronbach’s alpha is considered to be a very appropriate measurement way to evaluate the reliability [71]. In order to test the reliability and validity of the questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) indexes were selected to test the reliability of the questionnaire, and the results showed that, Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) values were both over 0.79, so the internal consistency reliability was high and acceptable.

Measuring the correspondence between the measured items and variables is called structural validity, which is constantly used in research. There are two methods to measure structural validity, one is exploratory factor analysis, the other is confirmatory factor analysis. The results showed that the KMO value was over 0.7, and the significance of Barlette’s test of sphericity was lower than 0.001, indicating that the questionnaire had good validity [72]. AMOS 26.0 was available for construction of the structural equation model, and the path coefficients between the measured variables and the latent variables could be obtained by calculation, and the CR and AVE values were calculated. The results showed that CR and AVE values outweigh 0.79 and 0.56, proving that the model showed fine convergence validity [73]. Table 3 also proved that discriminative validity between variables was supported because the estimated correlation among the whole constructs was lower than their respective square root of AVE [74].

4.3.2. Model Test

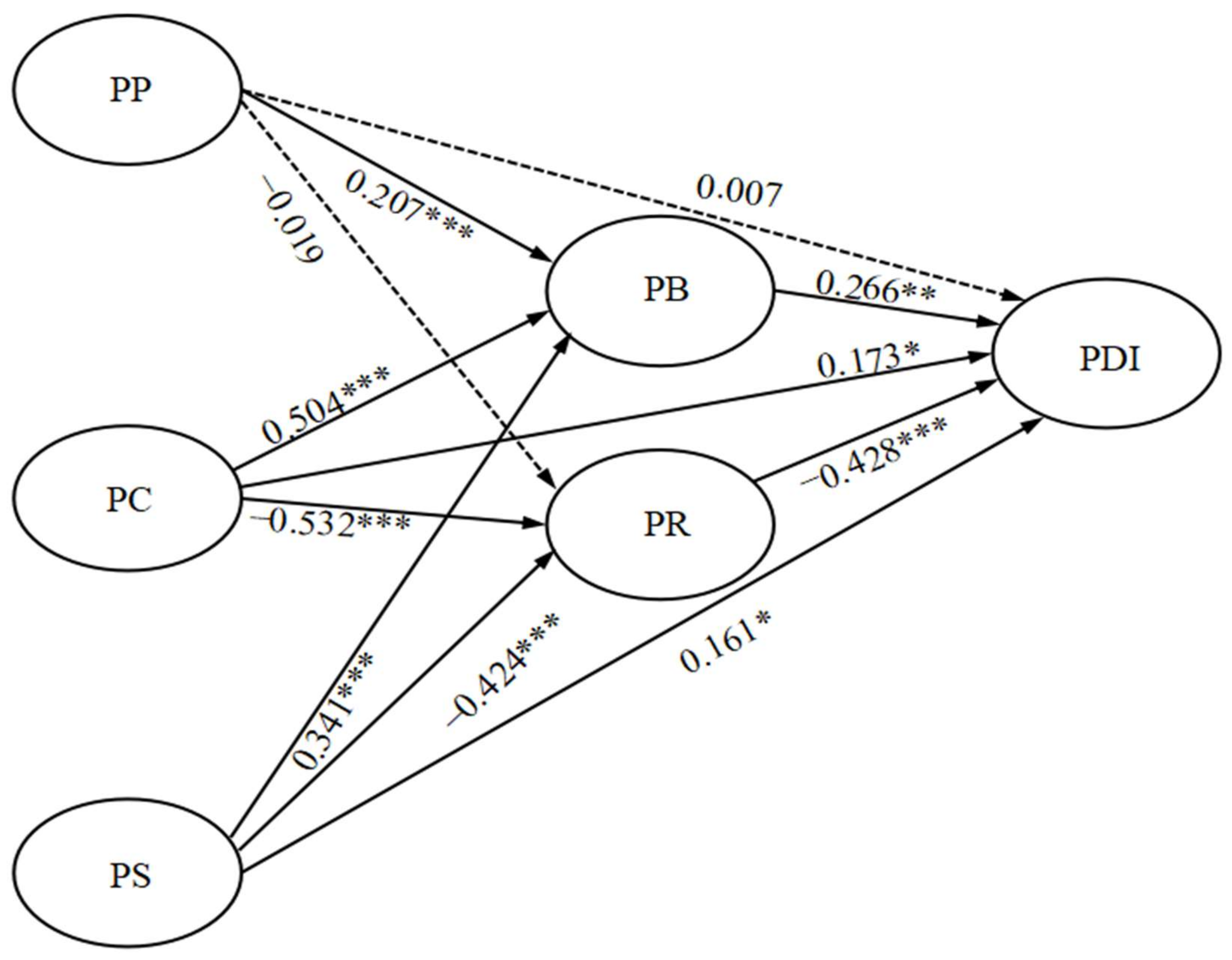

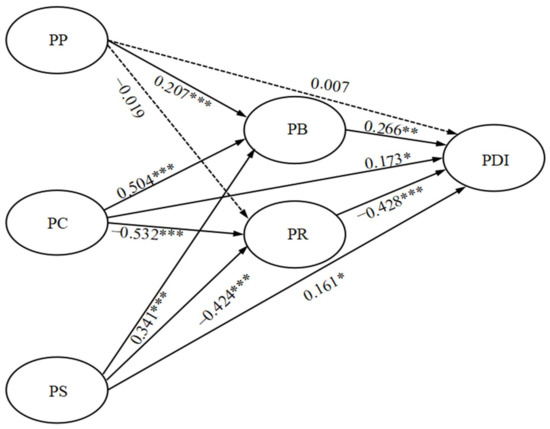

This paper used AMOS 26.0 to identify and evaluate the structural model (Figure 2 showed the results). The values shown in the figure were standardized path coefficients. The value of the standardized coefficient reflected the degree of influence, and the positive and negative values indicated positive or negative correlation. In addition, the standardized path coefficient between different measurement variables could be directly compared to measure the relative change level between various variables. The model fitting index was used to investigate the extent of fit between data and theoretical structure model. A variety of fitting indexes were provided in AMOS, and fit indices of CFA in this study was χ2 = 899.318; Df = 445; χ2/df = 2.021; CFI = 0.962; GFI = 0.85; TLI = 0.962; RMSEA = 0.056. In general, the model had a good fitting degree and was acceptable for fitting [75].

Figure 2.

Measurement model. (Remark: * means p < 0.05; ** means p < 0.01; *** means p < 0.001.).

4.3.3. Parameter Estimation and Hypothesis Testing

The method of maximum likelihood was used to calculate the research model in this study. C. R. represented the critical ratio, correspond to the t-test value. Supposing that its absolute value showed more than 1.96, that meant that the evaluated value achieved the significant level of p = 0.05. If its absolute value was greater than 2.58, it indicated that the estimated value had reached the significant level of p = 0.01. When the parameter estimation value reached the significant level, the path coefficient was supported by the data, while the path coefficient that did not reach the significant level was not supported by the data. When the significance p value was less than 0.001, the symbol “***” would be displayed; when the significance p value was > 0.001, the p-value would be directly displayed in the p-value. Standardized structural coefficients were listed as standardized regression coefficient values, which represented the influence of common factors on measured variables and could reflect the relative importance of each underlying factor. The structural equation model estimates are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Hypothetical results among variables.

As illustrated in Figure 2 and Table 4, the testing results showed that 11 hypotheses (H1, H4–H11) were supported. Significantly, PP (H1: β = 0.207, p < 0.001 had a significant effect on PDI, supporting H1. Additionally, PC (H4: β = 0.504, p < 0.001; H5: β = −0.532, p < 0.001; H6: β = −0.173, p < 0.05) had significant effects on PB, PR, and PDI, respectively, the hypotheses of H4–H6 were supported. In addition, PS had significant effect on PB, PR, and PDI, respectively. Therefore, H7–H9 was supported. Furthermore, the effect of PB and PR on PDI was 1% and 0.1%, respectively, supporting the hypothesis of H10 and H11. However, PP had no significant effect on PR and PDI. Therefore, H1b and H1c were not supported.

However, previous studies have shown that compared with young users, older users are more scared of their privacy being leaked so that they are more concerned about their privacy and risk [76]. That means younger users are less likely to see perceived risks, it may affect our H2 and H3 hypothetical results. Therefore, we did the age group analysis on perceived personalization, perceived risks, and privacy disclosure intention for further study, considering the sampling size, we divided the age into two groups (≤30 years old and >30 years old). The results showed that there were no big differences among two age groups (p > 0.05), that is to say, our findings of the hypotheses H2 and H3 were not affected by age (Refer to Table 5 for details).

Table 5.

Group statistics and independent sample test.

4.3.4. The Mediating Effect of Privacy Calculus

The mediation model was tested when controlling for gender and age, and the consequences are described in Table 6 and Table 7. The inspection results of path “perceived personalization → perceived benefits, perceived risks → privacy disclosure intention (Model 1)” displayed that perceived personalization had no remarkable positive effect on privacy disclosure intention (B = 0.031, p = 1.263), while perceived personalization had a significant positive impact on perceived benefits (B = 0.498, p < 0.001). Perceived benefits had a significant positive impact on privacy disclosure intention (B = 0.374, p < 0.001). The Bootstrap 95% confidence interval of the mediating effect of perceived benefits were (0.195, 0.397), indicating that perceived benefits played a complete mediating role in perceived personalization and privacy disclosure intention, thus supporting the H12 hypothesis. However, the positive impact of perceived personalization on perceived risk was not established, so the hypothesis of H15 was not supported.

Table 6.

Mediating effect test results.

Table 7.

The test results of decomposition effect.

The test results of the mediation model “perceived control → perceived benefits, perceived risks → privacy disclosure intention (Model 2)” demonstrated that perceived control had a notable positive effect on privacy disclosure intention (B = 0.317, p < 0.001), and perceived control had a significant positive impact on perceived benefits (B = 0.824, p < 0.001). Perceived benefits had a significant positive impact on privacy disclosure intention (B = 0.260, p < 0.001). The direct effect of perceived control on privacy disclosure intention and the mediating effect of perceived benefits accounted for 35.544% and 25.108% of the total effect, respectively, indicating that perceived benefits played a partial mediating role in perceived control and privacy disclosure intention, indicating that hypothesis H13 was valid. In addition, perceived control had a significant positive impact on privacy disclosure intention (B = 0.317, p < 0.001), perceived control had a significant negative impact on perceived risks (B = −0.863, p < 0.001), and perceived risks had a significant negative impact on privacy disclosure intention (B = −0.401, p < 0.001). The direct influence of perceived control on intention to privacy disclosure and the mediation of perceived risks accounted for 35.544% and 39.358% of the total effect, respectively, indicating that perceived risks played a partial mediating role in perceived control and privacy disclosure intention, that is, hypothesis H16 was established.

The test results of the mediation model “perceived similarity → perceived benefits, perceived risks → privacy disclosure intention (Model 3)” showed that perceived similarity had a remarkable positive effect on perceived benefits (B = 0.804, p < 0.001), and perceived benefits showed a significant positive impact on privacy disclosure intention (B = 0.275, p < 0.001). After the introduction of mediating variables, perceived similarity had a significant positive effect on privacy disclosure intention (B = 0.308, p < 0.001). In addition, perceived similarity of privacy disclosure would directly affect and the confidence interval of the mediation effect of perceived benefits were not contain 0, which suggested that perceived similarity affected privacy disclosure intention through the mediating effect of perceived benefits, and perceived benefits played a partial mediating role in perceived similarity and privacy disclosure intention, the assumption H14 was established. In addition, perceived similarity had a remarkable negative effect on perceived risks (B = −0.853, p < 0.001), perceived risks had a notable negative effect on privacy disclosure intention (B = −0.398, p < 0.001), and perceived similarity had a significant positive impact on privacy disclosure intention after the introduction of mediation variables (B = 0.308, p < 0.001). The direct impact of perceived similarity on privacy disclosure intention and the mediating effect of perceived risks accounted for 34.911% and 38.895% of the total effect, respectively, indicating that perceived risks played a partial mediating role in perceived similarity and privacy disclosure intention, i.e., hypothesis H17 was established.

5. Discussion

The SOR model and social interaction were used to study the mediating effects of perceived personalization, perceived control, perceived similarity, and intention to disclose in privacy calculus. SEM was used to check the research hypothesis. The major results of this paper are as below.

First of all, concerning the user’s man–computer interaction, the research results showed that perceived personalization had a remarkable effect on perceived benefits, perceived control had a positive effect on private calculus (namely perceived benefits and perceived risks) and privacy disclosure intention. Our research results are consistent with previous literature. In other words, Park [45] believed that users’ perceived individuation had a notable positive effect on perceived benefits. Princi and Kramer and Liu et al. [15,51] believed that user perceived control had a positive effect on perceived benefits and willingness to disclose privacy, and a negative impact on perceived risks. Moreover, concerning users’ interpersonal interaction, the research findings found that perceived similarity showed a positive effect on perceived benefits and privacy disclosure intention, and a negative impact on perceived risks, which is consistent with the results of previous literature (Needham and Vaske [57] and Trepte et al. [17]). That is to say, users with more perception of similarity have more perception of privacy benefits, and they are more likely to disclose privacy. However, perceived personalization has no effect on perceived risks and privacy disclosure intention, it is different from prevenient research results (Kang and Namkung [14] and Mou et al. [46]). There may be two reasons for this: first, the platform’s personalized service technology is embodied in the collection of users personal data disclosure, but for users, this procedure is continuous and invisible. When the function of personalized service works, users will promptly experience its convenience, rather than initially being aware of platforms using their personal information (Li et al. [77]). Second, although users perceive the benefits brought by personalized services, users who have been exposed to personal information abuse or who have already become victims of private information abuse may have high privacy concerns (Smith et al. [78]).

Secondly, in terms of privacy calculus, the results showed that perceived benefits had a significant positive impact on privacy disclosure intention, while perceived risks had a significant negative impact on privacy disclosure intention. Our results are the same as previous research where privacy calculus is considered to be an important predictor of privacy disclosure. It is worth noting that in social media, both perceived benefits and perceived risks play a critical role in privacy disclosure, it implies that users prefer to conduct rational risk–benefit assessment in their hearts before making privacy disclosure decisions when stimulated by the external environment.

Finally, privacy calculus showed mediating effect between users’ privacy disclosure intention and interactivity (i.e., perceived personalization, perceived control, and perceived similarity). As expected, there was an underlying relationship between perceived personalization, perceived control, perceived similarity, and intention to disclose privacy. However, perceived risk did not show an intermediary relationship between privacy disclosure intention and perceived personalization. This is not consistent with our forecast. One possible reason is that when users interact with social media platforms, they first experience the benefits and values brought by their personalized services rather than privacy risks [77].

6. Conclusions

With the development of mobile Internet, more and more organizations and individuals use various social media and applications in their daily life for business and personal activities. Meanwhile, people are likewise faced with higher privacy risks of inadvertently disclosing personal privacy on social media. How to facilitate users to enjoy safe and convenient services has become the primary problem to be resolved for the sustainable development of social media platforms. Based on the SOR theoretical model and privacy calculus theory, this study explored the relationship between human–computer interaction and interpersonal interaction (for instance, perceived personalization, perceived control, and perceived similarity), privacy calculus (such as perceived benefits and perceived risks), and privacy disclosure intention. In the meantime, the mediating effect of privacy calculus between user interaction and privacy disclosure intention is discussed. The results showed that perceived personalization, perceived control, and perceived similarity were significantly positively correlated with perceived benefits, while perceived control and perceived similarity were significantly negatively correlated with perceived risks. Perceived control, perceived similarity, and privacy calculus have significant influence on privacy disclosure intention. In addition, privacy calculus shows an intermediary relationship between privacy disclosure intention and perceived personalization, perceived control, and perceived similarity.

Compared with the existing research, the theoretical contribution of this study is primarily shown below two aspects.

- (1)

- Starting from the characteristics of human–computer interaction and interpersonal interaction, and based on the internal psychological characteristics of privacy calculus theory, the model of privacy disclosure intention of social media users is constructed, which takes into account the dual factors of platform characteristics and internal psychological perception, and expands the research perspective of privacy disclosure intention. Other previous studies combined the PCT and other theories, while this study, based on the introduction of the interactive features and privacy, examines the human–computer interaction and interpersonal interaction influence on social media users privacy disclosure intention; at the same time, it explores the perceived benefits and perceived risks in the dual interaction of privacy disclosure as an intermediary role, and enriches the theoretical study in the realm of social media privacy disclosure.

- (2)

- In terms of the SOR model and PCT, through analyzing the characteristic of interactivity with the combination of the two theories, this research summarized the human–computer interaction and interpersonal interaction to external stimulation factors, the perceived benefits and perceived risks as inner body awareness to explore how these factors affect the privacy disclosure intention, it extended the understanding of the two theories. This contribution not only thoroughly analyzed the inherent psychological trade-offs in privacy calculus theory, but also complements the SOR theoretical model.

Based on above, three inspirations can be drawn:

- (1)

- Social media should attach great importance to the human–computer interaction design of the platform, which can improve the operability of the platform and optimize the design of personalized services. Platforms should fully protect users’ privacy in social media and give them more rights to set privacy protection settings, so that consumers can develop a stronger awareness of control over privacy protection in social media and promote users’ intention to disclose privacy in social media by reducing privacy risk perception. In addition, while strengthening the construction of information security, the platform can establish a good information feedback mechanism, reinforce the interestingness and interactivity of social media, and strive to provide users with more targeted information to push services to enhance the perception of users’ benefits.

- (2)

- Social media platforms also should attach importance to promoting the interaction between the users, by providing some observable correlation function, which allows users awareness of each other between similarity, such as setting up “like”, “common concern”, “near”, “age”, and other functions, increases the user perceived benefits, reduces the perceived risks, thus enhances the privacy disclosure.

- (3)

- Regulators and social media platforms should focus on and protect users who are accustomed to disclosing their privacy. Users’ privacy disclosure data on social media platforms can be classified according to privacy disclosure levels, and users with great degree of privacy disclosure and potential privacy security problems can be given early warning reminders. For example, relevant users should be reminded to close location information as much as possible during privacy disclosure and reduce the visible range of personal information in the moment.

The model in this paper has obtained good feedback results in the empirical study, which proves that the combination of text data analysis results and structural equation model research has practical significance and shows a practical effect in the study of user privacy disclosure behavior, in order to make contributions to the development of the privacy disclosure behavior field.

Author Contributions

X.Z.: Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing. Q.C.: Writing—original draft, Investigation, Data processing. C.L.: Writing—review and editing, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is the research result of the National Natural Science Foundation of China “Research on the Fluctuation mechanism and optimization of user information demand considering the effects of media and crisis type”, the funder is Chunnian Liu and the project number is 72064027.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require ethical review and approval. In fact, we conducted questionnaires in mainland China and strictly complied with the regulations in the Personal Information Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China. At the beginning of our questionnaire survey, “This survey is an anonymous survey, only for our research learning this time. This questionnaire research is completely dependent on your voluntary help. All your information will be kept strictly confidential and will be cleared after the investigation. We would appreciate it if you could spare a few minutes of your time to participate in this investigation”.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Our questionnaire design is as follows.

Table A1.

Our questionnaire design is as follows.

| Latent Variables | Question Items | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Personalization (PP) | PP1 | TikTok can provide me with personalized messages and short videos. | Lee et al. (2015) |

| PP2 | TikTok can provide me with corresponding push messages according to my interests and hobbies. | ||

| PP3 | TikTok’s personalized features and services meet my individual needs. | ||

| Privacy Control (PC) | PC1 | I feel I am able to control the message I provide on TikTok APP. | Lee et al. (2015) |

| PC2 | I can use TikTok’s privacy Settings. | ||

| PC3 | I think I can control who can see me on TikTok APP. | ||

| PC4 | I can control whether private information is used by TikTok platform or my friends. | ||

| Perceived Similarity (PS) | PS1 | I can find some users with similar value orientation on TikTok APP. | Liu et al. (2016) |

| PS2 | I can find users who share similar information with me on TikTok APP. | ||

| PS3 | I can find users with similar interests on TikTok APP. | ||

| PS4 | I can find some users who have similar preferences for short video genres on TikTok APP. | ||

| Perceived Benefits (PB) | PB1 | I feel that posting more information can better serve my social needs. | Khang et al. (2014) |

| PB2 | I feel that I can make more like-minded friends by posting more information. | ||

| PB3 | I feel that posting more information will increase the number of visits to friends. | ||

| PB4 | I feel that Posting more information increases my pleasure in communicating with others. | ||

| Perveived Risk (PR) | PR1 | Posting personal information on TikTok APP has the risk of privacy leakage. | Zlatolas et al. (2019) |

| PR2 | Personal information posted on TikTok APP may be used inappropriately. | ||

| PR3 | Posting personal information on TikTok APP can cause unpredictable problems. | ||

| PR4 | Posting personal information on TikTok APP is dangerous. | ||

| Privacy Disclosure Intention (PDI) | PDI1 | I feel happy to disclose my private information on TikTok APP. | Zhao et al. (2012) |

| PDI2 | I often give out my personal information on TikTok APP. | ||

| PDI3 | I plan to continue to disclose my personal information on TikTok APP in the future. | ||

| PDI4 | I may disclose more personal information on TikTok in the future. | ||

References

- Whiting, A.; Williams, D. Why people use social media: A uses and gratifications approach. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2013, 16, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guan, M.; Hammond, P.; E Berrey, L. Communicating COVID-19 information on TikTok: A content analysis of TikTok videos from official accounts featured in the COVID-19 information hub. Heal. Educ. Res. 2021, 36, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revell, T. How Facebook let a friend pass my data to Cambridge Analytica. The New Scientist. 2018. Available online: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2166435-how-facebook-let-a-friend-pass-my-data-to-cambridge-analytica/ (accessed on 31 May 2018).

- Meral, K.Z. Social media short video-sharing TikTok application and ethics: Data privacy and addiction issues. In Multidisciplinary Approaches to Ethics in the Digital Era; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, J.; Nowak, G.; Ferrell, E. Privacy Concerns and Consumer Willingness to Provide Personal Information. J. Public Policy Mark. 2000, 19, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.B.; Vance, A.; Kirwan, C.B.; Jenkins, J.L.; Eargle, D. From Warning to Wallpaper: Why the Brain Habituates to Security Warnings and What Can Be Done About It. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2016, 33, 713–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, R.S.; Wolfe, M. Privacy as a concept and a social issue: A multidimensional developmental theory. J. Soc. Issues 1977, 33, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.T. Revisiting the privacy paradox on social media with an extended privacy calculus model: The effect of privacy concerns, privacy self-efficacy, and social capital on privacy management. Am. Behav. Sci. 2018, 62, 1392–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, N.; Shen, X.L.; Zhang, J.X. Location information disclosure in location-based social network services: Privacy calculus, benefit structure, and gender differences. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 52, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienlin, T.; Metzger, M.J. An extended privacy calculus model for SNSs: Analyzing self-disclosure and self-withdrawal in a representative US sample. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2016, 21, 368–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Heng, C.S.; Choi, B.C. Research note—Privacy concerns and privacy-protective behavior in synchronous online social interactions. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Moon, J.; Kim, Y.J.; Mun, Y.Y. Antecedents and consequences of mobile phone usability: Linking simplicity and interactivity to satisfaction, trust, and brand loyalty. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Lu, J.; Guo, L.; Li, W. The dynamic effect of interactivity on customer engagement behavior through tie strength: Evidence from live streaming commerce platforms. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 56, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.W.; Namkung, Y. The role of personalization on continuance intention in food service mobile apps: A privacy calculus perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 734–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Princi, E.; Krämer, N.C. Out of control–privacy calculus and the effect of perceived control and moral considerations on the usage of IoT healthcare devices. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 582054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Chu, H.; Huang, Q.; Chen, X. Enhancing the flow experience of consumers in China through interpersonal interaction in social commerce. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trepte, S.; Scharkow, M.; Dienlin, T. The privacy calculus contextualized: The influence of affordances. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 104, 106115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Jai, T.M.C.; Burns, L.D.; King, N.J. The effect of behavioral tracking practices on consumers’ shopping evaluations and repurchase intention toward trusted online retailers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Gupta, S.; Zhao, L. What motivates customers to participate in social commerce? The impact of technological environments and virtual customer experiences. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 1017–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremayne, M. Lessons learned from experiments with interactivity on the web. J. Interact. Advert. 2005, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, J.M. Customer interactivity and new product performance: Moderating effects of product newness and product embeddedness. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2010, 39, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.; Joginapelly, T. Effects of web atmospheric cues on users’ emotional responses in e-commerce. AIS Trans. Hum. -Comput. Interact. 2012, 4, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.L.; Novak, T.P. Marketing in hypermedia computer-mediated environments: Conceptual foundations. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, S.J.; Hwang, J.S. Measures of perceived interactivity: An exploration of the role of direction of communication, user control, and time in shaping perceptions of interactivity. J. Advert. 2002, 31, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Spielmann, N.; McMillan, S.J. Experience effects on interactivity: Functions, processes, and perceptions. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1543–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Wu, G. Conceptualizing and measuring the perceived interactivity of websites. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2006, 28, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Sun, J.; Yang, C.; Gu, C. The Impact of Perceived Interactivity and Intrinsic Value on Users’ Continuance Intention in Using Mobile Augmented Reality Virtual Shoe-Try-On Function. Systems 2021, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.C.; Huang, C.Y.; Chu, C.H.; Liao, H.C. Virtual community loyalty: An interpersonal-interaction perspective. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2010, 15, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culnan, M.J.; Bies, R.J. Consumer privacy: Balancing economic and justice considerations. J. Soc. Issues 2003, 59, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinev, T.; Hart, P. An extended privacy calculus model for e-commerce transactions. Inf. Syst. Res. 2006, 17, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Luo, X.R.; Carroll, J.M.; Rosson, M.B. The personalization privacy paradox: An exploratory study of decision making process for location-aware marketing. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 51, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Park, H.; Kim, J. Why do people share their context information on Social Network Services? A qualitative study and an experimental study on users’ behavior of balancing perceived benefit and risk. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2013, 71, 862–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.T.; Brock, J.L.; Shi, G.C.; Chu, R.; Tseng, T.H. Perceived benefits, perceived risk, and trust: Influences on consumers’ group buying behaviour. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2013, 25, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentina, I.; Zhang, L.; Bata, H.; Chen, Y. Exploring privacy paradox in information-sensitive mobile app adoption: A cross-cultural comparison. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 65, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, S.A.; Machleit, K.A.; Davis, L.M. Atmospheric qualities of online retailing: A conceptual model and implications. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 54, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, P. The role of affect in information systems research. In Human-Computer Interaction and Management Information Systems: Foundations; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, S.S.; Agarwal, J. Internet users’ information privacy concerns (IUIPC): The construct, the scale, and a causal model. Inf. Syst. Res. 2004, 15, 336–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajli, N.; Lin, X. Exploring the security of information sharing on social networking sites: The role of perceived control of information. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sarathy, R.; Xu, H. The role of affect and cognition on online consumers’ decision to disclose personal information to unfamiliar online vendors. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 51, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Li, X.; Wang, G. Are You Tired? I am: Trying to Understand Privacy Fatigue of Social Media Users. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 29 April–5 May 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. When does web-based personalization really work? The distinction between actual personalization and perceived personalization. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyheim, P.; Xu, S.; Zhang, L.; Mattila, A.S. Predictors of avoidance towards personalization of restaurant smartphone advertising: A study from the Millennials’ perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2015, 6, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H. The effects of personalization on user continuance in social networking sites. Inf. Processing Manag. 2014, 50, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, J.; Benyocef, M.; Kim, J. Benefits, risks and social factors in consumer acceptance of social commerce: A meta-analytic approach. Sage 2020, 125, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, S.Y. The effects of location personalization on individuals’ intention to use mobile services. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 53, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.B.; Zahay, D.L.; Thorbjørnsen, H.; Shavitt, S. Getting too personal: Reactance to highly personalized email solicitations. Mark. Lett. 2008, 19, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Hoekstra, J.C. Customization of online advertising: The role of intrusiveness. Mark. Lett. 2013, 24, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Duong, T.D.; Chen, C.C. Intention to disclose personal information via mobile applications: A privacy calculus perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Min, Q.; Li, W. The effect of role conflict on self-disclosure in social network sites: An integrated perspective of boundary regulation and dual process model. Inf. Syst. J. 2019, 29, 279–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusoglu, H.; Phan, T.Q.; Cavusoglu, H.; Airoldi, E.M. Assessing the impact of granular privacy controls on content sharing and disclosure on Facebook. Inf. Syst. Res. 2016, 27, 848–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trepte, S.; Reinecke, L.; Juechems, K. The social side of gaming: How playing online computer games creates online and offline social support. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. An overview (and underview) of research and theory within the attraction paradigm. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1997, 14, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Natour, S.; Benbasat, I.; Cenfetelli, R.T. The role of similarity in e-commerce interactions: The case of online shopping assistants. In Proceedings of the Special Interest Group on Human-Computer Interaction Conference, Portland, OR, USA, 2–7 April 2005; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kaptein, M.; Castaneda, D.; Fernandez, N.; Nass, C. Extending the similarity-attraction effect: The effects of when-similarity in computer-mediated communication. J. Comput. -Mediat. Commun. 2014, 19, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, M.D.; Vaske, J.J. Hunter perceptions of similarity and trust in wildlife agencies and personal risk associated with chronic wasting disease. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2008, 21, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosko, A.; Wood, E.; Molema, S. All about me: Disclosure in online social networking profiles: The case of FACEBOOK. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.Y.; Lu, H.P. Predicting mobile social network acceptance based on mobile value and social influence. Internet Res. 2015, 25, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teubner, T.; Flath, C.M. Privacy in the sharing economy. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2019, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Dinev, T.; Smith, H.J.; Hart, P. Examining the formation of individual’s privacy concerns: Toward an integrative view. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems, ICIS 2008, Paris, France, 14–17 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Li, H.; He, W.; Wang, F.K.; Jiao, S. A meta-analysis to explore privacy cognition and information disclosure of internet users. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 51, 102015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehr, F.; Kowatsch, T.; Wentzel, D.; Fleisch, E. Blissfully ignorant: The effects of general privacy concerns, general institutional trust, and affect in the privacy calculus. Inf. Syst. J. 2015, 25, 607–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khang, H.; Han, E.K.; Ki, E.J. Exploring influential social cognitive determinants of social media use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 36, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec Zlatolas, L.; Welzer, T.; Hölbl, M.; Heričko, M.; Kamišalić, A. A model of perception of privacy, trust, and self-disclosure on online social networks. Entropy 2019, 21, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lu, Y.; Gupta, S. Disclosure intention of location-related information in location-based social network services. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2012, 16, 53–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, S. Digital 2020: Global digital overview. Datareportal. 2020. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-global-digital-overview (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Iqbal, M. TikTok Revenue and Usage Statistics (2020). Business of Apps. 2020. Available online: https://www.businessofapps.com/data/tik-tok-statistics/ (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Demeulenaere, A.; Boudry, E.; Vanwynsberghe, H.; De Bonte, W. Onderzoeksrapport: De Digitale Leefwereld Van Kinderen; MEdiaraven: Gent, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Literat, I. “Teachers act like we’re robots” TikTok as a window into youth experiences of online learning during COVID-19. AERA Open 2021, 7, 2332858421995537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.S. Ecological correlations and the behavior of individuals. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 38, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Riefler, P.; Roth, K.P. Advancing formative measurement models. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 1203–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the use of structural equation models in experimental designs. J. Mark. Res. 1989, 26, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, P.Y.; Hu, P.J.H. Information technology acceptance by individual professionals: A model comparison approach. Decis. Sci. 2001, 32, 699–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Teo, H.H.; Tan, B.C.; Agarwal, R. The role of push-pull technology in privacy calculus: The case of location-based services. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2009, 26, 135–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Cheng, L.; Teng, C.I. Voluntary sharing and mandatory provision: Private information disclosure on social networking sites. Inf. Processing Manag. 2020, 57, 102128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J.; Milberg, S.J.; Burke, S.J. Information Privacy: Measuring Individuals’ Concerns about Organizational Practices. MIS Q. 1996, 20, 167–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).