Abstract

Digital Transformation is under constant evolution. Organizations that were not already created in the digital environment need to digitalize their services. The process used to do so may involve not only elements of technology, but also social, political and organizational aspects. While there is no holistic method to implement digital transformation, organizations learn from successful cases in order to build their own way to implement digital transformation. This paper presents the process through which a physically delivered service provided by the Brazilian federal government was transformed into a digital service. This was performed with a prototyping approach made of six steps: diagnose the service, analyze the service, identify the requirements, and elaborate, verify, and validate the prototype. To perform the digitalization, an automation tool was used, and there was constant interaction with the service provider. This article offers a detailed process to implement digitalization by means of prototyping, which can be used by other organizations to make services digital.

1. Introduction

According to Vial [1], Digital Transformation (DT) is “a process that aims to improve an entity by triggering significant changes to its properties through combinations of information, computing, communication, and connectivity technologies”. Although the term ‘digital transformation’ emerged in private organizations [2], public initiative soon became interested in this subject [3] as a means of increasing efficiency, effectiveness and ease of access. In addition, the modernization of service delivery allows for economic savings.

Many of the challenges listed by the Information Systems Special Commission [4], some of them related to the provision of information technology services to the Brazilian federal government, others to the new requirement for information systems or even to information transparency, yet others to the training of professionals, are even more critical when observed from a digital government point of view.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines digital government as the usage of digital technologies to modernize a government in order to aggregate public value [5]. Digital government can also be seen as an evolution from e-government [6]. While e-government is the use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) to achieve operational efficiency and consequently improve governance methods, digital government goes further, aiming at a paradigm shift in service delivering and transforming government procedures into “digital by design” [6]. For a government to become digital, it is necessary that its processes, schedules, and physical services become digital [7]. The transformation of physically delivered services into digitally ones is known as digitalization of a service. Digitalization is a very important phase in DT. Janowski [8] lists the digitalization process as the first step for a government to evolve to digital.

There are currently many initiatives to leverage digital government worldwide. As the most relevant ones, we can cite the Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies by OECD [5], and some analyses from the private initiative [7,9,10,11]. Very recently, DT is being applied in several countries, both in private initiative [12,13,14] and in federal and local governments [15,16,17,18,19,20,21].

Digital Transformation is not only focused on organizational features, but also in regulatory and institutional aspects, as changes to the law and work practice in agencies [22]. In this sense, the Brazilian federal government has increasingly supported the digitalization of public services. In 2016, a decree was published that defines a digital governance policy [23] and a digital citizenship platform [24].

In the digital governance policy [23], digital governance is defined as the usage, by the public sector, of communication and information technology resources to increase the availability of information and the provision of public services in order to encourage society’s participation in decision-making and improve the government levels of responsibility, transparency and effectiveness. Based on this decree, the Brazilian federal government produced the Strategy for Digital Governance [25].

The strategy for digital governance defines the strategic goals and the indicators of the Digital Governance Policy established by the decree. With this strategy, the Brazilian federal government aims to promote digital public services, enabling access to information and increasing social participation in public policy making.

The Digital Citizenship Platform decree [24] aims to enlarge and simplify the Brazilian citizens’ access to digital public services, including the usage of mobile applications. The Ministry of Economy (ME), as well as the central agency of the Brazilian public administration, has designed digital citizenship platform actions aligned with the strategy for digital governance, and, similarly to other countries [26], released a federal government services portal (https://www.gov.br/pt-br).

The services portal must be an integrated and unique channel that provides information and enables users to request services electronically and monitor public services. As we write this article, 3654 services are offered in t his portal (http://painelservicos.servicos.gov.br/) by the federal government, involving transactions from all government agencies.

Up to July of 2020, ME identified 2303 potential services for digital transformation. It is estimated that such transformation will generate annual savings of about BRL 1.2 billion to the government (approximately USD 269 million (Considering the dollar quote from 28 July 2020—USD 1 → BRL 5.19)) and BRL 2.2 billion to the society (approximately USD 423 million), since 77 million annual requests are expected from citizens. Among these potential services, 825 have already been digitalized, saving about BRL 484 million to the government (approximately USD 93 million) and about BRL 1.4 billion to the society, caused by approximately 65 million annual requests. ME observed, in a set of 626 digital services, that for each BRL 1 (approximately USD 0.19) invested in the digital transformation of services, an annual financial feedback of about BRL 22.32 (approximately USD 4.30) is obtained by the government and society, with a 59-day return on investment. Furthermore, bureaucracy has been reduced by a time saving of 149,087 h annually.

In the context of the Digital Citizenship Platform, ME set out strategies to implement digital transformation, which will be described in Section 2.2, in order to support public agencies from the federal government to identify, prioritize, digitalize, and deploy services with increased quality and transparency.

In this paper, we propose a process of digitalization of public services by means of a prototyping strategy, and we analyze the digitalization of one of the services provided by the Brazilian federal government. Although many processes and frameworks have been proposed in the last few years, each organization may need to develop its own strategy, since there is no holistic model for implementing digital government [27]. This development may be based on the experience of other organizations and cases applied to their own services. This is the main contribution of this work. Other organizations may use our proposal as a basis to create their own.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a literature review on DT, followed by a description of digital transformation of Brazilian public services. Section 3 covers the research design and methods applied in this work. Section 4 presents the digitalization process proposed. Section 5 explains how we applied this process to the transformation of a service provided in the federal government. Section 6 brings some discussion about the main findings of the study as well as the main challenges. Section 7 brings some final remarks.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Background

In general, the literature addresses DT in two approaches: on the one hand, focusing on a macro, theoretical overview of DT and its implication on organizations and in society. On the other hand, focusing on a technical approach, presenting frameworks and steps to achieve DT.

Moncayo and Anticona [27] identified four common phases of implementation of e-government: identification of information, creation of an interaction between the government and the citizens, establishment of online transactions and existence of a single electronic point for all government services. Nevertheless, they conclude that there is no holistic model that works for the implementation of e-government in general. This leads us to deduce that a good way of implementing e-government is to build a procedure based on other experiences.

Datta [28] said that besides technology, DT is much more about a sociotechnical and sociopolitical solution, which must generate changes in the underlying process of the service. Fischer et al. [29] identifies that the dimension of the challenge that DT constitutes involves actions from different areas, such as customer and partner engagement, business model innovation, process digitization and automation, digital platform management, data-driven agility, digital leadership, IT architecture transformation, and digital security and compliance.

Datta et al. [30] studied this aspect of DT in two services in Italy, and discussed its impacts over many areas, such as government transparency, corruption, sustainability, inclusivity, and simplification of bureaucracy. In fact, the literature shows that DT impacts and require changes in society, processes and policies.

Lindgren and van Veenstra [22] illustrated how the DT of public services impacts in the public sector transformation and aggregates public value. They observe that, besides changes in IT, processes and service organization, implications regarding legal changes and financial transparency by the government also occur.

Gong et al. [31] studied how do governments create flexibility to implement digital transformation. They studied the case of the government of Zhejiang Provence, which is located in the Yangtze River Delta on the southeast coast of the People’s Republic of China, employing a method that combines two frameworks: diamond framework [32], which proposes a conceptual organizational vision as a system composed of four elements (author, structure, tasks, and technology) to analyze the impact of technology, and TEF (technology enactment framework) [33], which aims to distinguish between “objective technology” and “enacted tecnology”. To understand the interdependence among organizational elements, authors used the Enterprise Architecture strategy [34]. They observed that technology, processes, structures, and eventually people, suffered radical or incremental changes, manifested in waves across different periods. Each of these waves implied more flexibility in the government.

Nonetheless, Jonathan [35] identified three factors related to the success on DT: (i) organizational and managerial factors, such as change in management, organizational culture, business-IT alignment, leadership engagement, and skills and development programme, (ii) environmental factors, such as funding, political stability, citizen participation regulatory frameworks, and telecommunications service quality, and (iii) information technology factors, such as data security, IT-architecture, interoperability, and data-driven agility. This shows how IT is essential to DT, not only in the DT itself [36], but also in the creation and development of services [37]. Besides these factors, Nielsen [38] and Nielsen and Jordanoski [39] concluded that (i) the governance model, (ii) the institutional ability for intergovernmental cooperation, and (iii) coordination are key factors for the success of DT.

We can find in the literature many processes of implementing DT. However, none of them are specific: we find general steps to achieve DT, without further details.

Irawati and Munajat [40], based on their experience on Indonesia, proposed a method to implement DT composed of three phases and 12 steps: (I) pre-implementation—(1) leadership and awareness, (2) institution building, (3) environmental analysis, (4) benchmarking; (II) implementation—(5) vision statement, (6) roadmap development, (7) strategy building, (8) management of critical factors, (9) system development; and (III) post-implementation—(10) evaluation, (11) operation, and (12) feedback.

Majaliwa and Simba [41] proposed a framework to analyze which government digital services can be accessed via mobile applications. The framework is composed of six steps: (1) situational analysis of the e-government system, (2) analysis of e-government services to be extended (purpose, interaction, transaction, feasibility study), (3) contents analysis and formatting, (4) analysis of infrastructure and technology requirements, (5) design and development stage, and (6) execution and piloting.

Many frameworks adopt a citizen-driven strategy. For instance, Axelsson and Melin [42] introduced a strategy that is composed of five phases to be executed with the citizen: (1) introduction, (2) brainstorming, (3) discussion of scenarios and prioritization of the importance of the information and electronic services discussed, (4) concepts discussion, and (5) prototype evaluation. van Velsen et al. [43] suggested five steps: (1) citizen interviews, (2) analysis of the interviews, (3) requirements notation, (4) prototype development and user walk-through, and (5) analysis of the walk-through. Djeddi and Djilali [44], in turn, stated a five-step framework: (1) domain analysis, (2) conceptual project, (3) prototyping, (4) evaluation, and (5) implementation.

Prototyping is assuming a central role in the digital transformation process [45,46], and Business Process Management (BPM) provides a clear way to describe tasks, activities, and assignments, as well as their connections to each other. Fischer et al. [29] presents a case study where five organizations (Lego Group (LEGO), SAP SE (SAP), Allianz Global Corporate and Specialty SE (AGCS), 1&1, and Taifun-Tofu GmbH (Taifun)) employ BPM on their DT process.

Leão and Canedo [47] investigated the main strategies adopted in the public sector and proposed a high-level eight-step model for the digitalization of public services in Brazilian government: (1) map the stakeholders (a general vision of everyone involved in the service), (2) identify the stakeholders (with interviews and surveys), (3) identify the communication channels to be used (e-mail, chat, social networks, among others), (4) identify needs, (5) identify the profile of citizens, (6) evaluate the services provided, (7) implement improvements on the services, and (8) implement a mechanism to maintain or encourage the use of the services.

We observed in the literature many interesting proposals for DT with different approaches, which explore aspects of prototyping, business processing management, enterprise architecture, and classical frameworks such as diamond and TEF. Withal, all of them converges to specific needs of organizations, therefore are not holistic models. Moreover, none of them exposes in detail the proposed approaches, instead providing a macro view of main features to be considered in DT. Nevertheless, presenting a more detailed model is an interesting contribution to the area, and this is the gap we explore in this work.

Summarizing, with the digital transformation of public services, government agencies aim to make service delivery more efficient and economic and, especially, to reach a higher level of citizen satisfaction, providing a more transparent public administration and increasing citizen participation in the public sector.

In particular, the Brazilian government has been working to develop and improve a strategy to implement digital government strongly based on prototyping and the use of Business Process Management (BPM) tools. We present a description of the Brazilian government strategy to DT, and a review on BPM in the subsequent.

2.2. Digital Transformation of Brazilian Public Services

The Brazilian government, with the Ministry of Economy (ME) and its Secretary of Digital Government (SGD), is working in a technological and strategical point of view to implement digital transformation. From the technological point of view, the government created the gov.br portal, which unifies all the digital channels from the federal government, offering the citizen a fast, direct, and unique channel to communicate to and to use the services provided by the federal government. Considering the great extent of Brazil and the large amount of agencies that make up the federal administration, the government has the audacious goal of integrating all sites by December 2020.

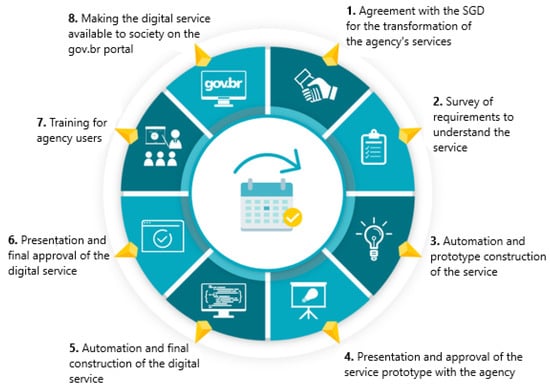

From the strategic point of view, one of the first initiatives from the Brazilian federal government was the Transformation Kit of Public Services [48], seeking the simplification and provision of services by digital media. This kit is a set of six independent phases, depicted in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Steps of the transformation kit (Adapted from [48]).

- To question aims to make a diagnosis of the services currently provided. This is focused on (i) prioritizing the most feasible services to become available in digital media, providing any necessary and desirable improvements in the process itself and (ii) analyzing the cost of these services and making a cost projection of the same services provided in digital media.

- To personalize aims to collect users’ expectations about the digital services and to verify if the solutions designed are simple and user-understandable after services have been chosen and analyzed in the to question phase.

- To reinvent evaluates alternatives to implement the solutions proposed in order to encourage creativity in the implementation process and improve the digital service. This phase requires various tests to assess the potential of the solutions proposed.

- To facilitate aims to provide digitalization and automation tools in order to simplify the digitalization of services.

- To integrate aims to integrate the solution developed with the existing databases of digital services already provided. This integration aims (i) to save the user from making registrations in different digitalized services and (ii) to unify the data avoiding inconsistencies between the digital services provided.

- To communicate has two main goals: (i) to publish the service after DT and to align information among managers, operators and users inside different sectors of the government and (ii) to advertise the new service to the target users.

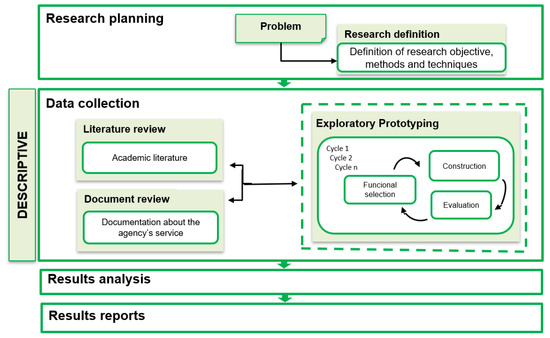

The Transformation Kit is constantly evolving. The most recent improvement was the automation platform, which is a framework composed of eight steps, illustrated in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Service automation steps (Adapted from [49]).

- Agreement with the SGD for the transformation of the agency’s services is the cooperation agreement to implement DT;

- Survey of requirements to understand the service: the SGD team elicits requirements to understand the service, the needs of the agency provider, and the information necessary to deliver the service;

- Automation and prototype construction: a preliminary version of the service prototype is developed;

- Presentation and approval of the service prototype with the agency: the service provider evaluates the prototype and checks if it meets the needs for delivering the service, defining any correction if needed;

- Automation and final construction of the digital service: taking into account the corrections raised in the previous step, the final version of the prototype is released and the service is digitalized;

- Presentation and final approval of the digital service;

- Training for agency users: the SGD team trains users to navigate in gov.br portal and to use the tools made available by ME;

- Making the digital service available to the society on the gov.br portal;

Providing digitalized services in an unique web portal, with the mediation of ME, has many advantages: reduction on queues and use of paper; economic savings, enabling investments in other areas; availability of the service at any time, except for technical failures; a unique login to use all services provided; accessible and easy service evaluation by the citizen; all the requirements can be transparently followed by the service provider and the citizen; and the costs of automation are covered by ME, not the agency digitalizing the service.

2.3. Business Process Management

Business Process Management (BPM) is a manner to understand business processes in a structured way. This understanding consists in documenting, modeling, analyzing, simulating, executing, and continuously improving the business process by adapting it to specific business performance demanded by organizations [50]. In order to expand the BPM from a concept to a holistic strategy, Rosemann and vom Brocke [51] proposed six capability areas: strategic alignment, governance, methods, IT, people, and culture. BPM has been successfully applied as a key for DT [29,52,53,54,55].

Many approaches to design BPM have been proposed since it was introduced. Featured in recent years, Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) appears and is proving to be a consolidated tool for modeling processes in the spirit of BPM. BPMN is a notation standard focusing on graphically express a process in a understandable fashion for all business users, since analysts that elaborate process until technical personnel that implement technology to perform the process [56]. BPMN is based on other classical notations and methods, such as UML Activity Diagram, UML EDOC Business Process, IDEF, ebXML BPSS, Activity-Decision Flow (ADF) Diagram, RosettaNet, LOVeM, and Event-driven Process Chains [57]. It offers a panoramic view of the whole process [58].

BPMN models four categories of objects: flow objects, connecting objects, swimlanes, and artifacts. Flow objects are events, activities and gateways. Activities represent what is done within an organization, an event is something that happens during the process, and gateways represent branching, forking, merging, or joining of paths within the process. Connecting objects are arrows that connect flow objects. Swimlanes are rectangles that represent actors involved in a process and contain all activities assigned to an actor. Artifacts are data objects, data stores, groups, and annotations. A more comprehensive and detailed description of BPMN diagrams and notations can be viewed in Object Management Group, Inc [56] and Aagesen and Krogstie [57].

3. Research Design and Methods

The methodological plan adopted in this work is composed of four phases: research planning, data collection, data analysis, and report of the results. This plan is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Methodological plan adopted in this work.

This research is classified as applied and qualitative, since we aim to analyze the results and intuitively to generate specific knowledge. As for the goals, the research is classified as descriptive, focusing on the identification of factors that characterize a phenomenon. About the means of investigation, bibliographic and documentary review procedures were used, complemented by exploratory prototyping.

The exploratory prototyping enables creative cooperation in order to explore the desired features [59]. It is composed of the following steps:

- Functional selection: elicitation of the service’s functional requirements. These requirements are the basis for the future prototype;

- Building: development of the prototype;

- Evaluation: feedback about the prototype.

These were adapted to this research scenario in interactive cycles, in order to enable the interaction among stakeholders, in a creative and collaborative way, until the approval of the prototype.

We considered the stakeholders divided into four groups:

- the researchers, that supported the prototyping process, which we denominated prototype team;

- the representatives of a central mediator agency;

- the representatives of the agency that delivered the service to be digitalized, which we denominated partner; and

- the representatives of a third-part company that offered a full BPM solution for digitalization.

With the theoretical foundation obtained with bibliographic revision, the prototype team planned the employment of templates to support the exploratory prototyping.

The data collection phase was supported by a combination of techniques for requirements elicitation [60,61]: document analysis, interview, Joint Application Development (JAD), prototyping, and BPMN:

- Document analysis: Araujo et al. [62] highlights documentary analysis as an important elicitation technique. We employed this technique by elaborating two templates that must be filled in by the mediator and delivered to the prototype team:

- Integration plan—contains the partner’s description and commitment to the digital transformation strategy of its public services. The template is depicted in Table 1.

Table 1. Integration plan template.

Table 1. Integration plan template. - Diagnostic plan—defines particularities of the service to be digitalized. We illustrate this template in Table 2.

Table 2. Diagnostic plan template.

Table 2. Diagnostic plan template.

- Interview: the interview is one of the most used and effective techniques for requirements elicitation [63,64]. We considered a mixed and open approach to the interview, with predefined initial questions. The template for the interview is presented in Table 3. The idea was to build an interview script composed by questions raised after the analysis of the integration plan, the diagnostic plan and the survey done about the service being digitalized.

Table 3. Interview template.

Table 3. Interview template. - JAD: this technique consists in an intensive structured workshop where different participants are present, such as facilitator, end users, developers, observers, mediators, and experts [65,66]. The meeting focuses on the customer and user business needs, disregarding the technical details of the solutions.

- Prototyping: the appearance and the functionality of the digitalized service are simulated from preliminary specifications, promoting clearer requirements and reducing gaps in understanding [29,44,45,46]. Many organizations consider the Business Process Management (BPM) as a baseline for digital transformation [29,46]. In this work, we are following the Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN).

- BPMN: see Section 2.3. Fischer et al. [29] emphasize that BPMN is a modeling notation and ISO/IEC standard is used to model, simulate, or execute business processes. The modeling elements of BPMN are designed to somehow express the process semantic and used primarily by business analysts, scientists, and tool vendors.

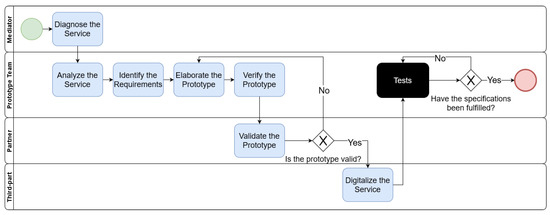

4. The Prototyping Process

We propose a prototyping process for the DT of public services composed of six steps, presented in Figure 4. Besides the literature about exploratory prototyping, introduced in Section 3, the practical experience of digitalizing services in the Brazilian government served as an inspiration for improving data collection in interviews and the prototyping process itself.

Figure 4.

Prototyping process.

As mentioned before, this process involves four actors: the prototype team, the partner, the mediator, and the third-part.

This process is designed to support the ’to facilitate’ phase of the Transformation Kit of Public Services and the steps 2, 3, and 4 from the automation platform (See Section 2.2). The focus of this process is requirements elicitation, from its understanding to the production and refinement of the digitalized service prototype.

4.1. Step 1: Diagnose the Service

This first step was performed by the mediator and the partner. The diagnostics must include all the information about the service, from operation to delivery. Two artifacts must be produced in this phase: the integration plan and the diagnostic form (according to the templates presented in Table 1 and Table 2 in Section 3).

4.2. Step 2: Analyze the Service

In this step, the prototype team examined the integration plan and the diagnostic form elaborated in the previous step. The intention was to extract an initial overview of the service scope and the provider’s goal with the digitalization process.

The prototype team may do further research about contents related to the service, such as online materials and legislation. All efforts must be directed to the production of the interview script in order to proceed to the ‘identify the requirements’ phase. The interview script was based on the interview template presented in Table 3 in Section 3.

4.3. Step 3: Identify the Requirements

This step was a joint work between the prototype team and the partner. Following the research plan, we applied interviews, JAD, and BPMN to elicit requirements. The main purpose of this step was to produce the following artifacts:

- Business workflow—describes the digitalized service workflow in the format of a BPMN diagram;

- Automation flow—describes the same process outlined by the workflow, but completely adapted to an automation tool;

- Requirements report—contains all the information about the service requirements, extracted from the interview and the ‘identify the requirements’ process;

- Data dictionary—includes information about the metadata from the fields of the form that will be used in the digitalized version of the service.

4.4. Step 4: Elaborate the Prototype

Before building the final digital version of the service, a prototype was developed. This phase consisted in:

- choosing an automation tool to build a prototype of the electronic form that would be the digital form of the service (this tool may have been provided by the third-part); and

- building a prototype using the chosen automation tool and the four artifacts produced in the previous step.

4.5. Step 5: Verify the Prototype

In this step, the prototype team tested the prototype to verify if its behavior and functionalities met all the service requirements. Although there were many automated tests, the manual method was more feasible in our context, since many characteristics were embedded in the prototype because of the service’s particular requirements.

Therefore, tests were defined to validate the functionalities according to the service requirements. We proposed to follow the adhoc methodology [67,68], where no documentation with the description of the test cases and their results is produced.

The main questions in this verification step were:

- Do the fields’ features match with the data dictionary?

- Is the diagram flow of the service routes arranged correctly?

- Are the service actors arranged correctly with their corresponding responsibilities?

- Are the business rules properly documented in the Automation flow and precisely implemented in the automation tool?

The verification should be repeated as long as there were corrections to be made in the prototype.

4.6. Step 6: Validate the Prototype

In this step, tests were performed by the partner to validate the solution implemented by the prototype team. The partner then produced the prototype adjustments table, which tracks the changes in the prototype requested during the testing phase.

The prototype team applied the adjustments proposed in the prototype, and Steps 5 and 6 were repeated until no more adjustments were needed.

After this phase, the prototype was delivered to the mediator along with all the artifacts produced.

5. Case Description

In this section, we present a case study of the application of the process presented in Section 4. In this case, the prototype team was ITRAC team, which supported the mediator, in this case ME, on the adaptation of the team workflow to the use of a BPM tool to the automation of forms.

The ME provided the BPM tool to the partner, which chose to make use of it, through an agreement (Step 1 of Automation Platform (see Figure 2)) at no extra cost to the partner. The tool ME made available was the Lecom BPM [69].

The service digitalized was the request for license of warehouses, terminals and enclosures for international transit of product of agricultural interest, hereafter simply called service. After the digitalization, the service was made available to the society on the gov.br portal;

This service was delivered by a Brazilian federal government ministry, which we considered as the partner for this case study.

The service used to be physically delivered in three phases, namely

- receiving request information about the license,

- manual processing of demands (i.e., acceptance or rejection of the request), and

- visualizing of the reports with the licensed establishments.

The requests used to be received in paper or digital format in Sistema Eletrônico de Infomações (SEI (http://www.fazenda.gov.br/sei/sobre)), an information system widely used in Brazilian federal institutions, in particular in ME. However, SEI did not support the processing of requests. Therefore, information about the processing and completion of the requests was stored in Microsoft Excel spreadsheets, from which the necessary reports were extracted.

In the following sections, we show how the steps presented in Section 4 were applied in the digitalization of the aforementioned service.

5.1. Step 1: Diagnose the Service

In this phase, the partner and ME identified together the main features of the service:

- its activities;

- its business workflow;

- its target audience;

- the average number of users;

- the data requested for the user to demand the service;

- the legislation about the service; and

- its digitalization requirements.

This information was registered in the diagnostic form. This form, along with the integration plan, formalized the beginning of the digitalization process of the service.

At the end of this step, the artifacts produced were sent to the ITRAC team to start the prototyping process.

5.2. Step 2: Analyze the Service

Service analysis led to the conclusion that the service should remain being delivered in three phases, though these should be better defined.

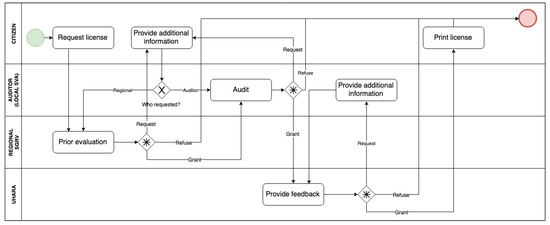

The requests were submitted through a standardized electronic form and addressed by three profiles of actors: (i) the REGIONAL, (ii) the AUDITOR, and (iii) the UHARA. The regional received the demand and forwarded it to an user from auditor profile, if all necessary information was provided, or returned it to the requester, if otherwise. The auditor needed to give an opinion about the process. This opinion may be (a) require additional information, (b) accepted, or (c) rejected. When the request received a “rejected” opinion from the auditor, it was sent to an user from the uhara profile to give the final opinion about the process. When the request received an “accepted” opinion, the requester was included in the list of licensed enclosures. The report was then generated based on this list.

The ITRAC team then produced the interview script elicited the requirements of the service. Some of the questions were:

- What are the necessary informations in the electronic form? Which of them are mandatory?

- Will the requester receive any certificate?

- Can the request be rejected at any phase of the evaluation process?

- Is it necessary to include a field to justify rejections?

5.3. Step 3: Identify the Requirements

In this step, the ITRAC team interviewed members from the partner and ME. The main points of the interview were (i) a description of the main goals of the service, (ii) an analysis of the preview of the Business workflow aiming to discuss improvements that would be brought by the automation tool, the Lecom BPM in this case, (iii) the standardization of the electronic forms for each step of the service execution.

One of the priorities in this phase was to produce the expected artifacts, which was done as follows.

- Service business workflow. There were four actors in this flow: the citizen, the regional, the auditor, and the uhara. The complete flow is illustrated in Figure 5. First, the citizen required the license and the request form was sent to the regional, who made a previous evaluation, possibly (i) rejecting the request, (ii) finalizing the process, (iii) asking for complementary information, or (iv) forwarding the request, appointing an auditor to proceed with the analysis. The auditor, in turn, could (i) reject, (ii) ask for complementary information, or (iii) accept the request, forwarding the process to the uhara which, in turn, could take the same positions. If accepted, the request returned to the citizen to print the record and finalize. A detailed explanation on each activity is on Table 4.

Figure 5. Service business workflow.

Figure 5. Service business workflow. Table 4. Activities of the service business process workflow, depicted in Figure 5.

Table 4. Activities of the service business process workflow, depicted in Figure 5. - Service automation flow. This was very similar to the business workflow, but it was suitable for the automation tool Lecom BPM and brings remarks of each activity of the business workflow, for instance:

- the citizen had 30 days to answer the complementary information requested by the regional. If no answer was obtained in this period, the process was finalized. On the other hand, the deadline was undetermined to answer to the complementary information request from the auditor.

- in the previous evaluation, the regional has 30 days to fill the evaluation form. In the 15th day, a notification e-mail was sent to the regional. If the regional did not fill the evaluation form until the 30th day, another e-mail was sent.

- Data dictionary. The data dictionary was divided into four topics, one for each actor. The citizen electronic form was organized in six sections: (1) information about the place to be licensed, (2) information about the customs type where the place was inserted, (3) information about the intended operations and the category of products to be moved, (4) documents attachment, (5) complementary information, and (6) commitment term. The regional form had an opinion field, an auditor indication field and an additional observations field. The auditor form had four parts: (1) general requirements, (2) specific requirements, (3) additional information, and (4) conclusion. Finally, the uhara form was very similar to the regional one.

5.4. Step 4: Elaborate the Prototype

In this step, a prototype was designed in Lecom BPM, according to the following phases.

- Some properties of the prototype were described, namely: the title, the subtitle, the situation, the category, the owner, and the table name.

- The functionalities in automation flow were included in the prototype.

- The actors responsible for each part of the prototype were defined, as well as the possible paths a request can take, namely the acceptance, the rejection and the solicitation of complementary information.

- The fields of the prototype were created. Based on the data dictionary, 375 fields were created, and the following properties were defined for each one: position, type, name, and label. Depending on the type, some further properties were also defined, like font size, background color, font color, alignment, field size, mask, tip, document attachment mode, number of lines, and number of columns.

- A table, which is a high-fidelity interface of the electronic form, was generated.

- The initial values of the fields were defined, as well as the setting of the read-only, blocked, mandatory and hidden fields.

- Some scripts were created to:

- turn fields visible and invisible depending on choices made in previous fields;

- change the content of a field according to choices made in previous fields;

- change the “finalize” button label of a screen according to the opinion given by the actor (accept, reject or ask for complementary information).

5.5. Step 5: Verify the Prototype

The verification was made during the development of the properties of the electronic form fields by the ITRAC team: it was observed if the behavior of the flow was as expected, all the possibilities of flows were tested.

After every failure was corrected, the appropriate correction was made, the prototype was properly versioned, and all the tests were performed again.

After the verification was concluded, a meeting with ME and the partner was held in order to present the prototype and make changes before validation.

5.6. Step 6: Validate the Prototype

The validation consists in making the prototype available for the partner and ME to perform the desired tests. For this, the ITRAC team created a test user for each actor of the service. The team also produced an user manual and the online version of the prototype adjustments table to be filled by the test users.

After validation, 25 changes were requested. The ITRAC team made the changes and finished the prototyping process, making the final version of the prototype available to be implemented in the federal government services portal.

6. Discussion

Digitalization has been an issue for information systems research for decades, and has been recently enhanced by the wave of digital revolution. Governments are increasingly investing in DT, as a strategic priority, and devoting efforts to mobilize the most diverse areas involved in the DT process [29,45].

Although many works in the literature employ BPM in the digitalization process [29,46], none of them brings the level of detail that we exhibit in this work. Besides, BPM provides only information about the process itself, and not about the context in which it is inserted. Some initiatives are being taken to address this issue, such as integrating semantic-based approaches to BPM, like ontologies that describe BPMN semantically [70,71].

During the development of this work, we found out how BPM is a key tool to understand processes before DT, which is an essential step for the success of DT. We noticed that there is no model that is suitable for DT in any organization, therefore, the development of a strategy must rely on the own organization reality and in the experience of others, which may contribute to specific points when developing a new method for DT. This is probably the main difficulty for organizations when implementing DT. Consequently, works like ours collaborate to build a sense in order to elaborate DT strategies.

Since this work is a descriptive research, the proposed process was elaborated from the abstraction of elements that we observed in a set of study cases. Furthermore, the case we describe in this work (Section 5) is an example of how the proposed process was employed in a real case.

Although the strategy we presented requires the interaction between all the stakeholders, which can favor the evolution of the service during the DT process, we don’t include a method to guarantee the innovation of the service. This could be achieved by the creation of a step aiming to promote a user-centered service evolution, with simplicity.

Last, but not least, in our case study, we observed the difficulty that the partners had to explain the whole process of their service delivery. Certainly, high-level approaches to facilitate this phase would be welcome.

7. Final Remarks

In this paper, the process of digitalization of a Brazilian public service was described. This process, also called prototyping process, was composed of six steps: diagnose the service, analyze the service, identify the requirements, and elaborate, verify, and validate the prototype. To perform the digitalization, an automation tool was used, and there was constant interaction with the stakeholders. As a result, a model that may be systematically applied to the digitalization of similar services was designed. This is a relevant contribution to the literature, which is still being built in this area.

The proposed process is being used in the Brazilian federal government since 2017 and, as we write this work, 244 public services were digitalized, in the most diverse areas such as national surveillance, agriculture and livestock, health, labor and public finances. In the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, some services were digitalized in a record time, such as the unemployment aid application, which took three days to be digitalized. Up to July 2020, more than 1 million of protocols were opened by 550 thousand citizens, whose satisfaction assessment shows 4.25 points out of 5.0, carried out by more than 316 thousand people that answered the survey.

As future studies, we highlight (i) the application of the digitalization process proposed in other governmental agencies, (ii) improvements in the process, such as strategies to promote service innovation during DT, (iii) the evaluation of other automation tools to support the digitalization process, and (iv) a semantic-based strategy to add context to BPM applied to DT.

Author Contributions

Data curation, L.G.P. and S.M.A.; project administration, R.M.C.F., C.S.R. and L.C.M.R.J.; software, L.G.P. and S.M.A.; supervision, J.L.G., R.M.C.F., C.S.R. and L.C.M.R.J.; Writing—original draft, L.G.P., S.M.A., R.M.C.F. and C.S.R.; writing—review and editing, J.L.G. and R.M.C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Economy grant number GEPRO_TED_MP_SEGES_AUTOMACão_2017.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergel, I.; Edelmann, N.; Haug, N. Defining digital transformation: Results from expert interviews. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leão, H.A.T.; Canedo, E.D. Digitization of Public Services: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 17th Brazilian Symposium on Software Quality, Curitiba, Brazil, 17–19 October 2018; pp. 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscarioli, C.; Araujo, R.M.; Maciel, R.S.P. I GranDSI-BR—Grand Research Challenges in Information Systems in Brazil 2016–2026; Special Committee on Information Systems (CE-SI); Brazilian Computer Society (SBC): Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies; Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Digital Government. In Broadband Policies for Latin America and the Caribbean: A Digital Economy Toolkit; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016; Chapter 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, G.C.; Palmer, D.; Phillips, A.N.; Kiron, D.; Buckley, N. Strategy, Not Technology, Drives Digital Transformation; Deloitte University Press: London, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/cn/Documents/technology-media-telecommunications/deloitte-cn-tmt-strategy-not-technologydrive-digital-transformation-en-150930.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Janowski, T. Digital government evolution: From transformation to contextualization. Gov. Inf. Q. 2015, 32, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accenture Consulting. Digital Government: “Good Enough for Government” Is Not Good Enough; Accenture Consulting: Dublin, Ireland, 2016; Available online: https://www.accenture.com/t20160912t095949__w__/us-en/_acnmedia/pdf-30/accenture-digital-citizen-experience-pulse-survey-pov.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Chanias, S.; Myers, M.D.; Hess, T. Digital transformation strategy making in pre-digital organizations: The case of a financial services provider. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, G. Government Portals Are Evolving to Enable Digital Government; Gartner Inc.: Stamford, CT, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/documents/2995021/government-portals-are-evolving-to-enable-digital-govern (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Marolt, M.; Pucihar, A.; Lenart, G.; Vidmar, D. Digital transformation scoreboard—Case of Slovenia and Croatia. In Proceedings of the 2019 42nd International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics (MIPRO), Opatija, Croatia, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 1380–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, D.T.; Angulo, L.; Sandoval, J.; Guerrero, C.D. Digital Transformation in Colombia: An Exploratory Study on ICT Adoption in Organizations. In Proceedings of the 2019 14th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Coimbra, Portugal, 19–22 June 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeow, A.; Soh, C.; Hansen, R. Aligning with new digital strategy: A dynamic capabilities approach. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2018, 27, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliannan, M.; Awang, H. Adoption and Use of E-Government Services: A Case Study on E-Procurement in Malaysia. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ. 2010, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, D.; Khemchandani, V. Study of e-governance in India: A survey. Int. J. Electron. Secur. Digit. Forensics 2019, 11, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A.; Teigland, R. Digital Transformation and Public Services: Societal Impacts in Sweden and Beyond; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, R.D. The influence of digital transformation of government on peruvian citizen trust. In Proceedings of the Twenty-fifth Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS), Cancún, Mexico, 15–17 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, J.P. Service, Openness and Engagement as Digitally-Based Enablers of Public Value: A Critical Examination of Digital Government in Canada. Int. J. Public Adm. Digit. Age 2019, 6, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.A.; Zuntini, J.I. Digital readiness in government: The case of Bahía Blanca municipal government. Int. J. Electron. Gov. 2019, 11, 155–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Rakhmatullayev, Z.M. Digital Transformation of the Public Service Delivery System in Uzbekistan. In Proceedings of the 2019 21st International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT), Pyeongchang, Korea, 17–20 February 2019; pp. 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, I.; van Veenstra, A.F. Digital Government Transformation: A Case Illustrating Public e-Service Development as Part of Public Sector Transformation. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research: Governance in the Data Age, Delft, The Netherlands, 30 May–1 June 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil. Decreto n. 8.638, de 15 de janeiro de 2016. Política de Governança Digital. 2016. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/CCIVIL_03/_Ato2015-2018/2016/Decreto/D8638.htm (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Brazil. Decreto n. 8.936, de 19 de dezembro de 2016. Plataforma de Cidadania Digital. 2016. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2016/decreto/D8936.htm (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Brazil, Ministry of Economy. Estratégia de Governo Digital 2020–2022. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.br/governodigital/pt-br/EGD2020 (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- Luna-Reyes, L.F.; Gil-Garcia, J.R. Digital government transformation and internet portals: The co-evolution of technology, organizations, and institutions. Gov. Inf. Q. 2014, 31, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncayo, M.B.; Anticona, M.T. A systematic review based on Kitchengam’s criteria about use of specific models to implement e-government solutions. In Proceedings of the 2016 Third International Conference on eDemocracy eGovernment (ICEDEG), Sangolquí, Ecuador, 30 March–1 April 2016; pp. 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, P. Digital Transformation of the Italian Public Administration: A Case Study. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2020, 46, 252–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Imgrund, F.; Janiesch, C.; Winkelmann, A. Strategy archetypes for digital transformation: Defining meta objectives using business process management. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, P.; Walker, L.; Amarilli, F. Digital transformation: Learning from Italy’s public administration. J. Inf. Technol. Teach. Cases 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Yang, J.; Shi, X. Towards a comprehensive understanding of digital transformation in government: Analysis of flexibility and enterprise architecture. Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37, 101487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavitt, H.J. Applied organizational change in industry: Structural, technological and humanistic approaches. In Handbook of Organizations; March, J.G., Ed.; Rand McNally & Co.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1965; pp. 1144–1170. [Google Scholar]

- Fountain, J.E. Building the Virtual State: Information Technology and Institutional Change; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kitsios, F.; Kamariotou, M. Business strategy modelling based on enterprise architecture: A state of the art review. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2019, 25, 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonathan, G.M. Digital Transformation in the Public Sector: Identifying Critical Success Factors. In Information Systems; Themistocleous, M., Papadaki, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynov, V.V.; Shavaleeva, D.N.; Zaytseva, A.A. Information Technology as the Basis for Transformation into a Digital Society and Industry 5.0. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference Quality Management, Transport and Information Security, Information Technologies (IT QM IS), Sochi, Russia, 23–27 September 2019. pp. 539–543. [CrossRef]

- Kitsios, F.; Kamariotou, M. Service innovation process digitization: Areas for exploitation and exploration. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.M. Governance Lessons from Denmark’s Digital Transformation. In Proceedings of the 20th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, Dubai, UAE, 18–20 June 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.M.; Jordanoski, Z. Digital Transformation, Governance and Coordination Models: A Comparative Study of Australia, Denmark and the Republic of Korea. In The 21st Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawati, I.; Munajat, E. Electronic government assessment in West Java province, Indonesia. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2018, 96, 365–381. [Google Scholar]

- Majaliwa, A.; Simba, F. Development of Extension Procedures to Enhance web-based e-Government System with SMS Mobile Based Service. In Proceedings of the 2019 IST-Africa Week Conference (IST-Africa), Nairobi, Kenya, 8–10 May 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, K.; Melin, U. Citizen Participation and Involvement in eGovernment Projects: An Emergent Framework. In Electronic Government; Wimmer, M.A., Scholl, H.J., Ferro, E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Velsen, L.; van der Geest, T.; ter Hedde, M.; Derks, W. Requirements engineering for e-Government services: A citizen-centric approach and case study. Gov. Inf. Q. 2009, 26, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djeddi, A.; Djilali, I. A User Centered Ubiquitous Government Design Framework. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Information Processing, Security and Advanced Communication. Association for Computing Machinery, IPAC ’15, Batna, Algeria, 23–25 November 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legner, C.; Eymann, T.; Hess, T.; Matt, C.; Böhmann, T.; Drews, P.; Mädche, A.; Urbach, N.; Ahlemann, F. Digitalization: Opportunity and Challenge for the Business and Information Systems Engineering Community. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2017, 59, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, S.; Silva, J.; Lopes, N.; Ribeiro, O.; Mariz, C. Technical assistance to school network using BPM. In Proceedings of the 2018 13th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Caceres, Spain, 13–16 June 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leão, H.; Canedo, E. Best Practices and Methodologies to Promote the Digitization of Public Services Citizen-Driven: A Systematic Literature Review. Information 2018, 9, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, R.M.C.; Soares, V.A.; Martins, L.B.; Almeida, M.L.F.A.; Melo, L.S.; Ramos, C.S. Governo Digital Brasileiro: Relatório Técnico; Technical Report; Faculty UnB Gama, University of Brasilia: Brasília, Brazil, 2019; Available online: https://repositorio.unb.br/handle/10482/34787 (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Brazil, Ministry of Economy. Automação de Serviços. 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.br/governodigital/pt-br/transformacao-digital/ferramentas/automacao-de-servicos (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- Recker, J.; Indulska, M.; Michael; Green, P. How good is BPMN really? Insights from theory and practice. In Proceedings of the ECIS 2006 Proceedings, Göteborg, Sweden, 12–14 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rosemann, M.; vom Brocke, J. The Six Core Elements of Business Process Management. In Handbook on Business Process Management 1: Introduction, Methods, and Information Systems; vom Brocke, J., Rosemann, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L. Digital Transformation with Business Process Management; Future Strategies: Lighthouse Point, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baiyere, A.; Salmela, H.; Tapanainen, T. Digital transformation and the new logics of business process management. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 238–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, H.; Valença, G.; Alves, C. Strategies for Managing Critical Success Factors of BPM Initiatives in Brazilian Public Organizations: A Qualitative Empirical Study. iSys Rev. Brasil. Sistemas Inform. 2015, 8, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vom Brocke, J.; Mendling, J. Business Process Management Cases: Digital Innovation and Business Transformation in Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Object Management Group, Inc. Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) Version 2.0.2; Object Management Group, Inc.: Needham, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aagesen, G.; Krogstie, J. BPMN 2.0 for Modeling Business Processes. In Handbook on Business Process Management 1: Introduction, Methods, and Information Systems; vom Brocke, J., Rosemann, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 219–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinosi, M.; Trombetta, A. BPMN: An introduction to the standard. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2012, 34, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, C. A Systematic Look at Prototyping. In Approaches to Prototyping; Budde, R., Kuhlenkamp, K., Mathiassen, L., Züllighoven, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Mishra, A.; Yazici, A. Successful requirement elicitation by combining requirement engineering techniques. In Proceedings of the 2008 First International Conference on the Applications of Digital Information and Web Technologies (ICADIWT), Ostrava, Czech Republic, 4–6 August 2008; pp. 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, C.; García, I.; Reyes, M. Requirements elicitation techniques: A systematic literature review based on the maturity of the techniques. IET Softw. 2018, 12, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, A.F.; Oliveira, J.L.; Silva, A.F.; Machado, B.N.; Louzada, J.A.; Soares, P.M. An Approach to Requirements Engineering Applied to Information Systems. In Proceedings of the XII Brazilian Symposium on Information Systems on Brazilian Symposium on Information Systems: Information Systems in the Cloud Computing Era—Volume 1, Florianópolis, Brazil, 17–22 May 2016; Brazilian Computer Society: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2016; pp. 184–191. [Google Scholar]

- Aurum, A.; Wohlin, C. Engineering and Managing Software Requirements; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, A.; Dieste, O.; Hickey, A.; Juristo, N.; Moreno, A.M. Effectiveness of Requirements Elicitation Techniques: Empirical Results Derived from a Systematic Review. In Proceedings of the 14th IEEE International Requirements Engineering Conference (RE’06), St. Paul, MN, USA, 11–15 September 2006; pp. 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- August, J. Joint Application Design: The Group Session Approach to System Design; Prentice Hall, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Liou, Y.I.; Chen, M. Using Group Support Systems and Joint Application Development for Requirements Specification. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1993, 10, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agruss, C.; Johnson, B. Ad Hoc Software Testing: A Perspective on Exploration And Improvisation; Florida Institute of Technology: Melbourne, FL, USA, 2000; pp. 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra, N. Introduction To Adhoc Testing. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2012, 1, 66–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lecom. BPM Studio. 2019. Available online: https://www.lecom.com.br/plataforma-lecom/bpm/ (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Di Martino, B.; Esposito, A.; Nacchia, S.; Maisto, S.A. Semantic Annotation of BPMN: Current Approaches and New Methodologies. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Information Integration and Web-Based Applications & Services, Brussels, Belgium, 11–13 December 2015; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.B.; Santoro, F.M.; Mira da Silva, M. An Ontology for BPM in Digital Transformation and Innovation. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Model. Des. 2020, 11, 52–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).