Preventative Nudges: Introducing Risk Cues for Supporting Online Self-Disclosure Decisions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Contribution

2. Related Work

2.1. Self-Disclosure Behavior in SNSs

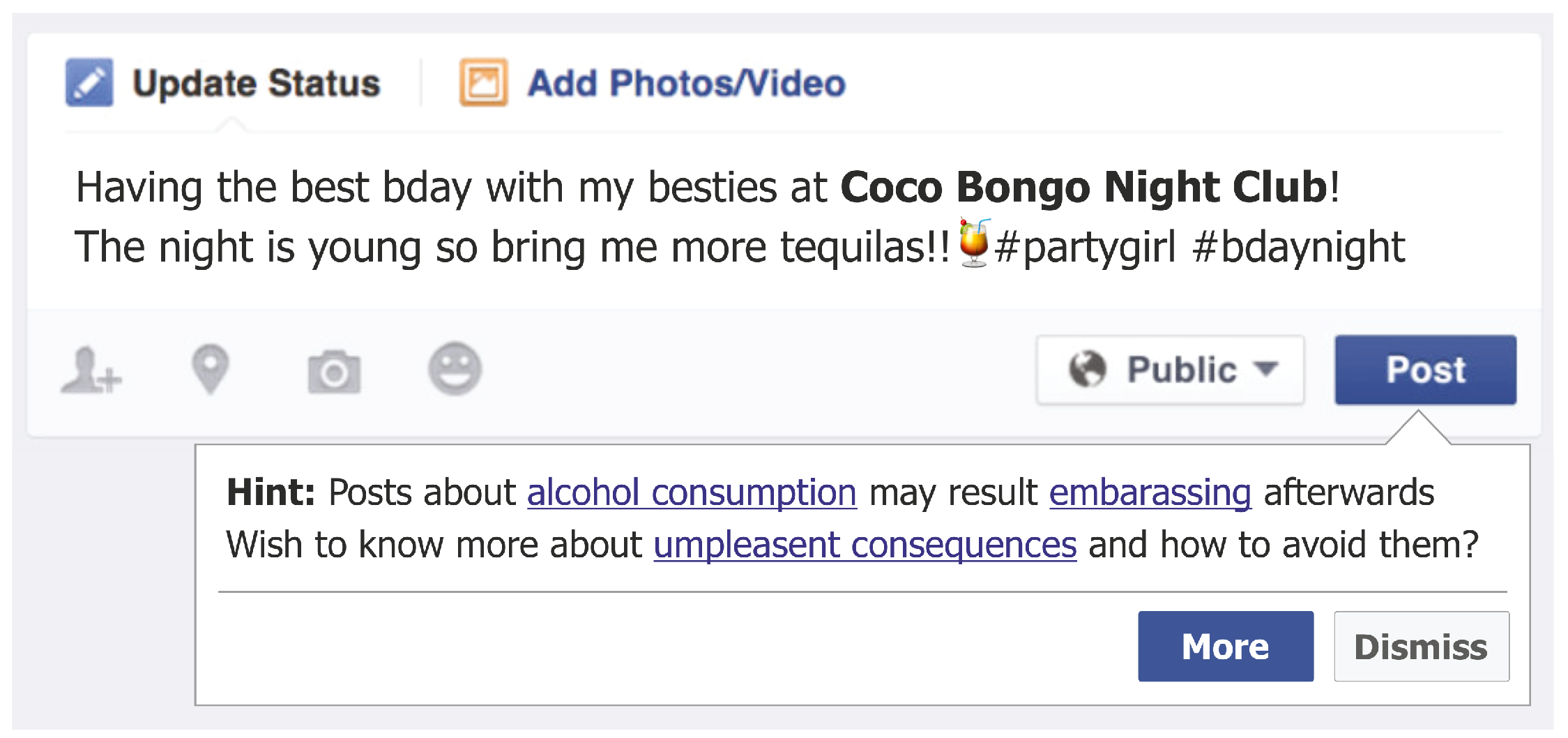

2.2. Preventative Nudges

3. Theoretical Background

3.1. Self-Disclosure Patterns

3.2. Personalized Risk Awareness

4. Method

4.1. Survey Design

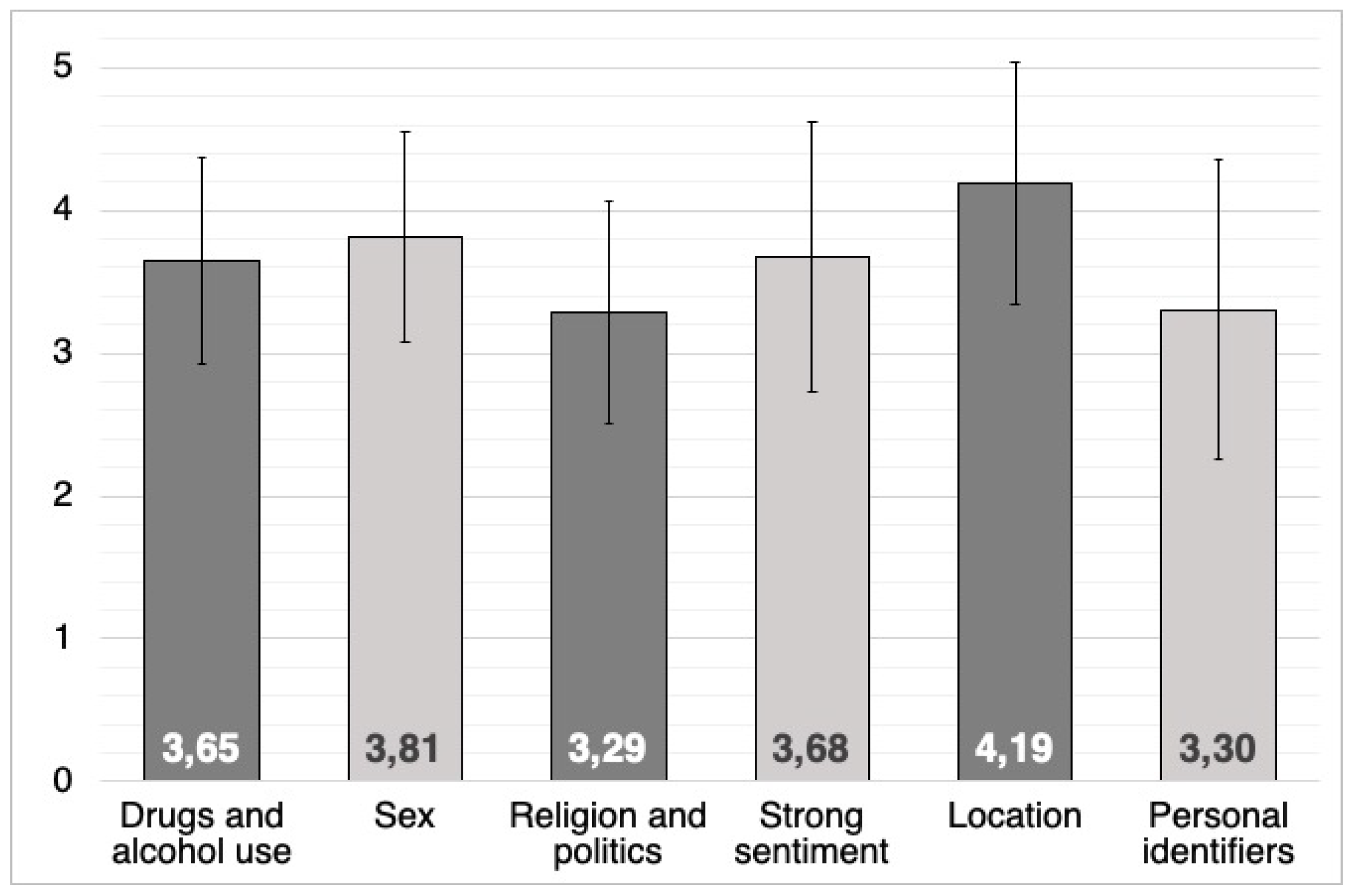

- Drugs and alcohol use: These scenarios correspond to situations in which people may suffer unwanted incidents after posting information related to their consumption habits of alcohol or drugs.

- Sex: Scenarios defined under this category represent cases where people are liable to experience negative consequences after sharing details about their sexual life in SNSs.

- Religion and politics: These scenarios describe negative consequences that may occur when sharing a political statement or disclosing one’s religious affiliation in online platforms.

- Strong sentiment: This category groups together scenarios in which unwanted incidents can take place as a result of sharing content with a strong or negative sentiment.

- Location: These scenarios describe unwanted incidents that are likely to occur when people reveal their current location or places they frequently visit inside their posts.

- Personal identifiers: Scenarios defined under this category portray situations in which negative consequences can occur after sharing information containing personal identifiers such as one’s credit card or social security numbers.

4.2. Population and Sampling

5. Results and Findings

5.1. Assessment of Self-disclosure Scenarios

5.2. Effects of Risk-Based Interventions

6. Personalized Risk-Based Interventions

6.1. Content, Frequency and Timing

6.2. Intervention Approach

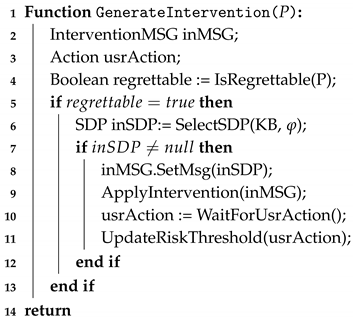

| Algorithm 1: Personalized interventions |

|

7. Discussion

8. Limitations

9. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SNS | Social Network Site |

| SDP | Self-Disclosure Pattern |

| UIN | Unwanted Incident |

| PA | Private Attribute |

Appendix A. Studied Sample

| Demographic | Ranges | Freq. | Responses (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–25 years | 29 | 10.3 |

| 26–35 years | 135 | 48 | |

| 36–45 years | 66 | 23.5 | |

| 46–55 years | 31 | 11 | |

| > 56 years | 20 | 7.12 | |

| Gender | Male | 156 | 55.5 |

| Female | 123 | 43.8 | |

| Non-binary | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Occupation | Employed full time | 205 | 73 |

| Employed part time | 34 | 12.1 | |

| Unemployed and not searching for work | 13 | 4.6 | |

| Unemployed searching for work | 8 | 2.8 | |

| Disabled or retired | 7 | 2.5 | |

| Student | 14 | 5 | |

| Education | Graduate degree (MSc, PhD) | 44 | 15.7 |

| Undergraduate degree (BSc, BA) | 104 | 37 | |

| Some college | 87 | 31 | |

| High school or less | 43 | 15.3 | |

| Primary school or less | 3 | 1.1 |

Appendix B. ANOVA Posthoc Test

| Category | N | Mean | SD | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (I) Drugs and alcohol use | 281 | 3.649 | 0.728 | 0.043 |

| (II) Sex | 281 | 3.811 | 0.737 | 0.044 |

| (III) Religion and politics | 281 | 3.288 | 0.782 | 0.047 |

| (IV) Strong sentiment | 281 | 3.676 | 0.951 | 0.057 |

| (V) Location | 281 | 4.185 | 0.850 | 0.051 |

| (VI) Personal identifiers | 281 | 3.302 | 1.051 | 1.051 |

| SS | d.f. | MS | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between groups | 158.654 | 5 | 31.731 | 43.075 | 0.000 |

| Within groups | 1237.573 | 1680 | 0.737 | ||

| Total | 1396.227 | 1685 |

| Difference of Levels | Difference of Means | SE | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| drugs and alcohol use—sex | −0.162 | 0.062 | 0.094 | (−0.339, 0.015) |

| drugs and alcohol use—religion and politics | 0.361 * | 0.064 | 0.000 | (0.179, 0.544) |

| drugs and alcohol use—strong sentiment | −0.027 | 0.072 | 0.999 | (−0.231, 0.178) |

| drugs and alcohol use—location | −0.536 * | 0.067 | 0.000 | (−0.727, −0.345) |

| drugs and alcohol use—personal identifiers | −0.347 * | 0.076 | 0.000 | (0.129, 0.365) |

| sex—religion and politics | 0.523 * | 0.064 | 0.000 | (0.340, 0.707) |

| sex—strong sentiment | 0.135 | 0.072 | 0.413 | (−0.070, 0.341) |

| sex—location | −0.374 * | 0.067 | 0.000 | (−0.566, −0.182) |

| sex—personal identifiers | 0.509 * | 0.077 | 0.000 | (0.290, 0.728) |

| religion and politics—strong sentiment | −0.388 * | 0.074 | 0.000 | (−0.598, −0.178) |

| religion and politics—location | −0.897 * | 0.069 | 0.000 | (−1.109, −0.700) |

| religion and politics—personal identifiers | −0.014 | 0.078 | 1.000 | (-0.238, 0.209) |

| strong sentiment—location | −0.509 * | 0.076 | 0.000 | (−0.727, −0.291) |

| strong sentiment—personal identifiers | 0.374 * | 0.085 | 0.000 | (0.132, 0.616) |

| location—personal identifiers | 0.883 * | 0.081 | 0.000 | (0.652, 1.113) |

Appendix C. Risk Criticality Index

Appendix D. Survey Instruments

- Q1: “Please indicate how severe is for you the consequence described in this scenario”. Options: insignificant, minor, moderate, major, or catastrophic.

- Q2: “Have you experienced a situation similar to that before?”. Options: yes, or no.

- Q3: (if the answer to Q2 was yes) “Have you deleted such content afterwards?”. Options: yes, or no.

Appendix D.1. Employed Constructs

- Social media is open and receptive to the needs of its members.

- Social media makes good-faith efforts to address most member concerns.

- Social media is also interested in the well-being of its members, not just its own.

- Social media is honest in its dealings with me.

- Social media keeps its commitments to its members.

- Social media is trustworthy.

- Other members on social media will do their best to help me.

- Other members on social media do care about the well-being of others.

- Other members on social media are open and receptive to the needs of each other.

- Other members on social media are honest in dealing with each other.

- Other members on social media keep their promises.

- Other members on social media are trustworthy.

- I feel in control over the information I provide on social media.

- Privacy settings allow me to have full control over the information I provide on social media.

- I feel in control of who can view my information on social media.

- I have a comprehensive profile on social media.

- I find time to keep my profile up to date.

- I keep my friends updated about what is going on in my life through social media.

- When I have something to say, I like to share it on social media.

- (R) Overall, I see no real threat to my privacy due to my presence on social media.

- I fear that something unpleasant can happen to me due to my presence on social media.

- (R) I feel safe publishing my personal information on social media.

- Overall, I find it risky to publish my personal information on social media.

- Please rate your overall perception of privacy risk involved when using social media.

Appendix D.2. Self-Disclosure Scenarios

- You share a post describing your experience with drugs. You get a wake-up call from your superior after a colleague forwards this post to him.

- You post a picture in which you are drunk at a party. You feel embarrassed after you realize this picture was seen by all your contacts including close friends, family and acquaintances.

- You share a post describing your experience with drugs. You lose your job after your work colleagues forward this post to your boss.

- You post a picture in which you are drunk at a party. You lose your job after your work colleagues forward this picture to your boss.

- You share a post describing your experience with drugs. You feel embarrassed after you realize this post was seen by all your contacts including close friends, family and acquaintances.

- You post a picture in which you are drunk at a party. You get a wake-up call from your superior after a colleague forwards this picture to him.

- 7.

- You post a naked or semi-naked picture of you. You lose your job after your work colleagues forward this picture to your boss.

- 8.

- You post a naked or semi-naked picture of you. You get a wake-up call from your superior after a colleague forwards this picture to him.

- 9.

- You share a post describing a personal sexual encounter or experience. You feel embarrassed after you realize this post was seen by all your contacts including close friends, family and acquaintances.

- 10.

- You share a post describing a personal sexual encounter or experience. You get a wake-up call from your superior after a colleague forwards this post to him.

- 11.

- You post a naked or semi-naked picture of you. You feel embarrassed after you realize this picture was seen by all your contacts including close friends, family and acquaintances.

- 12.

- You share a post describing a personal sexual encounter or experience. You feel embarrassed after you realize this post was seen by all your contacts including close friends, family and acquaintances.

- 13.

- You share a post giving your opinion about a religious issue or statement. You lose your job after your work colleagues forward this post to your boss.

- 14.

- You share a post giving your opinion about a political issue or statement. You get a wake-up call from your superior after a colleague forwards this post to him.

- 15.

- You share a post giving your opinion about a religious issue or statement. Some of your friends decide to end up their relationship with you because they found your post offensive.

- 16.

- You share a post giving your opinion about a political issue or statement. Some of your friends decide to end up their relationship with you because they disagree with what you wrote.

- 17.

- You share a post giving your opinion about a religious issue or statement. You get a wake-up call from your superior after a colleague forwards this post to him.

- 18.

- You share a post giving your opinion about a political issue or statement. You lose your job after your work colleagues forward this post to your boss.

- 19.

- You share a post with a negative comment about someone else. Friends in common decide to end up their relationship with you after seeing what you wrote.

- 20.

- You share a post with a negative comment about your employer. You get a wake-up call from your superior after a colleague forwards this post to him.

- 21.

- You share a post with a negative comment about your employer. You lose your job after your work colleagues forward this post to your boss.

- 22.

- You share a post and include the location where you are at the moment. You get stalked by a person who saw your post and is at the same place as you are.

- 23.

- You share a post including your new home address. Someone who saw your post breaks into your house to rob your belongings.

- 24.

- You share a post including your new phone number. You get messages and calls from a person who was not supposed to see your post.

- 25.

- You share a picture of your brand-new credit card. Some days later you realize that someone has been buying stuff on your behalf.

- 26.

- You share a post including your new email address. Thereafter, you start getting spam messages from someone you don’t know.

References

- Williams, D.J.; Noyes, J.M. How does our perception of risk influence decision-making? Implications for the design of risk information. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 2007, 8, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, N.J.S.; Glöckner, A.; Dickert, S. Conscious and unconscious thought in risky choice: Testing the capacity principle and the appropriate weighting principle of unconscious thought theory. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slovic, P.; Peters, E. Risk Perception and Affect. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 15, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, G.F.; Weber, E.U.; Hsee, C.K.; Welch, N. Risk as feelings. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, A.R.H. Perception of Product Risks. In Consumer Perception of Product Risks and Benefits; Emilien, G., Weitkunat, R., Lüdicke, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.K. Risk Communication. In Consumer Perception of Product Risks and Benefits; Emilien, G., Weitkunat, R., Lüdicke, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 125–149. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.J.; Aloe, A.M.; Feeley, T.H. Risk Information Seeking and Processing Model: A Meta-Analysis. J. Commun. 2014, 64, 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Burke, M.; Kraut, R. Modeling Self-Disclosure in Social Networking Sites. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, CSCW ’16, San Francisco, CA, USA, 27 February–2 March 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Acquisti, A.; Brandimarte, L.; Loewenstein, G. Privacy and human behavior in the age of information. Science 2015, 347, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampong, G.; Mensah, A.; Adu, A.; Addae, J.; Omoregie, O.; Ofori, K. Examining Self-Disclosure on Social Networking Sites: A Flow Theory and Privacy Perspective. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Such, J.M.; Criado, N. Multiparty Privacy in Social Media. Commun. ACM 2018, 61, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albladi, S.; Weir, G.R.S. Vulnerability to Social Engineering in Social Networks: A Proposed User-Centric Framework. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Cybercrime and Computer Forensic (ICCCF), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 12–14 June 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Krombholz, K.; Hobel, H.; Huber, M.; Weippl, E. Advanced social engineering attacks. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2015, 22, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitak, J. The Impact of Context Collapse and Privacy on Social Network Site Disclosures. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2012, 56, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Norcie, G.; Komanduri, S.; Acquisti, A.; Leon, P.G.; Cranor, L.F. “I regretted the minute I pressed share”: A Qualitative Study of Regrets on Facebook. In Proceedings of the ACM 7th Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security, SOUPS 2011, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 20–22 July 2011; pp. 1–16, ANSWER: Confirmed. [Google Scholar]

- Sundar, S.S.; Kang, H.; Wu, M.; Go, E.; Zhang, B. Unlocking the Privacy Paradox: Do Cognitive Heuristics Hold the Key? In Proceedings of the ACM CHI ’13 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Paris, France, 27 April–2 May 2013; pp. 811–816. [Google Scholar]

- Marmion, V.; Bishop, F.; Millard, D.E.; Stevenage, S.V. The Cognitive Heuristics Behind Disclosure Decisions. In Social Informatics. SocInfo 2017; Lecture Notes in Computer Science Series; Ciampaglia, G., Mashhadi, A., Yasseri, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10539, pp. 591–607. ISBN 978-3-319-67216-8. [Google Scholar]

- De, S.J.; Imine, A. On Consent in Online Social Networks: Privacy Impacts and Research Directions (Short Paper). In Risks and Security of Internet and Systems; Zemmari, A., Mosbah, M., Cuppens-Boulahia, N., Cuppens, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Krämer, N.C.; Schäwel, J. Mastering the challenge of balancing self-disclosure and privacy in social media. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 31, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosca, F.; Sarkadi, S.; Such, J.M.; McBurney, P. Agent EXPRI: Licence to Explain. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Explainable Transparent Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems (EXTRAAMAS), Auckland, New Zealand, 9–13 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, D.; Domingo-Ferrer, J.; Martínez, S. Co-utile Disclosure of Private Data in Social Networks. Inf. Sci. 2018, 441, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, G.; Such, J.M. PACMAN: Personal Agent for Access Control in Social Media. IEEE Internet Comput. 2017, 21, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Acquisti, A.; Adjerid, I.; Balebako, R.; Brandimarte, L.; Cranor, L.F.; Komanduri, S.; Leon, P.G.; Sadeh, N.; Schaub, F.; Sleeper, M.; et al. Nudges for Privacy and Security: Understanding and Assisting Users’ Choices Online. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2017, 50, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, Y.; Osman, M.; Ashcroft, R. Nudge: Concept, Effectiveness, and Ethics. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 39, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samat, S.; Acquisti, A. Format vs. Content: The Impact of Risk and Presentation on Disclosure Decisions. In Proceedings of the USENIX Association Thirteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS 2017), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 12–14 July 2017; pp. 377–384.

- Gerber, N.; Reinheimer, B.; Volkamer, M. Investigating People’s Privacy Risk Perception. Proc. Priv. Enhanc. Technol. 2019, 2019, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimeur, E.; Diaz Ferreyra, N.E.; Hage, H. Manipulation and Malicious Personalization: Exploring the Self-Disclosure Biases Exploited by Deceptive Attackers on Social Media. Front. Artif. Intell. 2019, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Díaz Ferreyra, N.E.; Meis, R.; Heisel, M. Learning from Online Regrets: From Deleted Posts to Risk Awareness in Social Network Sites. In Proceedings of the ACM 27th Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization, Larnaca, Cyprus, 9–12 June 2019; pp. 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Masaki, H.; Shibata, K.; Hoshino, S.; Ishihama, T.; Saito, N.; Yatani, K. Exploring Nudge Designs to Help Adolescent SNS Users Avoid Privacy and Safety Threats. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Peer, E.; Egelman, S.; Harbach, M.; Malkin, N.; Mathur, A.; Frik, A. Nudge Me Right: Personalizing Online Nudges to People’s Decision-Making Styles. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 109, 106347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warberg, L.; Acquisti, A.; Sicker, D. Can Privacy Nudges be Tailored to Individuals’ Decision Making and Personality Traits? In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society, WPES’19, London, UK, 11 November 2019; pp. 175–197. [Google Scholar]

- Kokolakis, S. Privacy attitudes and privacy behaviour: A review of current research on the privacy paradox phenomenon. Comput. Secur. 2017, 64, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.B. A Privacy Paradox: Social Networking in the United States. First Monday 2006, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienlin, T.; Metzger, M.J. An Extended Privacy Calculus Model for SNSs: Analyzing self-disclosure and Self-Withdrawal in a Representative U.S. Sample. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2016, 21, 368–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trepte, S.; Reinecke, L.; Ellison, N.B.; Quiring, O.; Yao, M.Z.; Ziegele, M. A Cross-Cultural Perspective on the Privacy Calculus. Soc. Media Soc. 2017, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.T. Revisiting the Privacy Paradox on Social Media With an Extended Privacy Calculus Model: The Effect of Privacy Concerns, Privacy Self-Efficacy, and Social Capital on Privacy Management. Am. Behav. Sci. 2018, 62, 1392–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spottswood, E.L.; Hancock, J.T. Should I Share That? Prompting Social Norms That Influence Privacy Behaviors on a Social Networking Site. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2017, 22, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambino, A.; Kim, J.; Sundar, S.S.; Ge, J.; Rosson, M.B. User Disbelief in Privacy Paradox: Heuristics That Determine Disclosure. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, ACM, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; pp. 2837–2843. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, M.J.; Flanagin, A.J. Credibility and trust of information in online environments: The use of cognitive heuristics. J. Pragmat. 2013, 59, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinmann, M.; Schneider, C.; vom Brocke, J. Digital Nudging. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2016, 58, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esposito, G.; Hernández, P.; van Bavel, R.; Vila, J. Nudging to prevent the purchase of incompatible digital products online: An experimental study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Damgaard, M.T.; Nielsen, H.S. The use of nudges and other behavioural approaches in education. Anal. Rep. Eur. Expert Netw. Econ. Educ. (EENEE) 2017, 29, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, V.A. Nudges for Health Policy: Effectiveness and Limitations. Mo. Law Rev. 2017, 82, 727. [Google Scholar]

- De, S.J.; Le Métayer, D. Privacy Risk Analysis to Enable Informed Privacy Settings. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW), London, UK, 23–27 April 2018; pp. 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Ferreyra, N.E. Instructional Awareness: A User-centred Approach for Risk Communication in Social Network Sites. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Duisburg-Essen, Duisburg Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkin, N.; Mathur, A.; Harbach, M.; Egelman, S. Personalized Security Messaging: Nudges for Compliance With Browser Warnings. In 2nd European Workshop on Usable Security (EuroUSEC); Internet Society: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guha, S.; Baumer, E.P.S.; Gay, G.K. Regrets, I’ve Had a Few: When Regretful Experiences Do (and Don’t) Compel Users to Leave Facebook. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM Conference on Supporting Groupwork, ACM, Sanibel Island, FL, USA, 7–10 January 2018; pp. 166–177. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, W.; Chen, K. Tweet Properly: Analyzing Deleted Tweets to Understand and Identify Regrettable Ones. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on World Wide Web, Montréal, QC, Canada, 11–15 April 2016; pp. 603–612. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council of European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679. 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679&from=EN (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Paolacci, G.; Chandler, J.; Ipeirotis, P.G. Running Experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2010, 5, 411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, P.G. Conducting Usable Privacy & Security Studies with Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS), Redmond, WA, USA, 14–16 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tips for Academic Requesters on Mturk. Available online: https://bit.ly/3dUAI0y (accessed on 7 August 2020).

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1992, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, F.; Balebako, R.; Cranor, L.F. Designing Effective Privacy Notices and Controls. IEEE Internet Comput. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfay, W.B.; Serna, J.; Pape, S. Challenges in Detecting Privacy Revealing Information in Unstructured Text. In Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Society, Privacy and the Semantic Web—Policy and Technology (PrivOn), Kobe, Japan, 18 October 2016; Brewster, C., Cheatham, M., d’Aquin, M., Decker, S., Kirrane, S., Eds.; CEUR Workshop Proceedings, CEUR-WS.org: Aachen, Germany, 2016; Volume 1750. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Son, H.Q.; Tran, M.T.; Yoshiura, H.; Sonehara, N.; Echizen, I. Anonymizing Personal Text Messages Posted in Online Social Networks and Detecting Disclosures of Personal Information. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2015, 98, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, T.; Stieglitz, S. Digital nudging and privacy: Improving decisions about self-disclosure in social networks. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2019, 1–19. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0144929X.2019.1584644 (accessed on 7 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Nemec Zlatolas, L.; Welzer, T.; Hölbl, M.; Heričko, M.; Kamišalić, A. A Model of Perception of Privacy, Trust, and Self-Disclosure on Online Social Networks. Entropy 2019, 21, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kittur, A.; Chi, E.H.; Suh, B. Crowdsourcing user studies with Mechanical Turk. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, ACM, Florence, Italy, 5–10 April 2008; pp. 453–456. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, J.; Wang, G. Evaluating Crowdsourcing Through Amazon Mechanical Turk as a Technique for Conducting Music Perception Experiments. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Music Perception and Cognition, Thessaloniki, Greece, 23–28 July 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Amazon. Mechanical Turk: Requester Best Practices Guide; Technical Report; Amazon Inc.: Bellevue, WA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Terpstra, A.; Schouten, A.P.; de Rooij, A.; Leenes, R.E. Improving privacy choice through design: How designing for reflection could support privacy self-management. First Monday 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinati, R.; Madaan, A.; Hall, W. InstaCan: Examining Deleted Content on Instagram. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Web Science Conference, ACM, Troy, NY, USA, 25–28 June 2017; pp. 267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Gazizullina, A.; Mazzara, M. Prediction of Twitter Message Deletion. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2019 12th International Conference on Developments in eSystems Engineering (DeSE), Kazan, Russia, 7–10 October 2019; pp. 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, T. Why is the government relying on nudge theory to fight Coronavirus? The Guardian. 13 March 2020. Available online: https://bit.ly/2WYEQGf (accessed on 7 August 2020).

- Renaud, K.; Zimmermann, V. Ethical guidelines for nudging in information security & privacy. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2018, 120, 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Facchinetti, S.; Osmetti, S.A. A Risk Index for Ordinal Variables and its Statistical Properties: A Priority of Intervention Indicator in Quality Control Framework. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2018, 34, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnova, H.; Spiekermann, S.; Koroleva, K.; Hildebrand, T. Online social networks: Why we disclose. J. Inf. Technol. 2010, 25, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sample Availability: All datasets generated for this study are can be found at the following online repository: https://uni-duisburg-essen.sciebo.de/s/ISyoWPgwEFuIxSE. |

| No. | Category | Scn. IDs | Example | SDP <PAs, Audience, UIN> |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Drugs and alcohol use | 1–6 | Scn. 6: “You post a picture of you drunk at a party. You feel embarrassed after your work colleagues forward the picture to your boss” | <alcohol consumption, work colleagues, embarrassment> |

| II | Sex | 7–12 | Scn. 8: “You post a naked or semi-naked picture of you. You get a wake-up call from your superior after a colleague shows it to her” | <nudity, work colleagues, employer warning> |

| III | Religion and politics | 13–18 | Scn. 15: “You share a post giving your opinion about a religious issue or statement. Some of your friends decide to end up their relationship with you because they found your post offensive” | <religious beliefs, close friends, end up friendship> |

| IV | Strong sentiment | 19–21 | Scn. 21: “You share a post with a negative comment about your employer. You lose your job after a work colleague forwards the post to your boss” | <employer judgement, work colleagues, job joss> |

| V | Location | 22–23 | Scn. 22: “You share a post and include the location where you are at the moment. You get stalked by a person who sees your post and is at the same place as you are” | <location, public, stalking> |

| VI | Personal identifiers | 24–26 | Scn. 24: “You share a post including your new phone number. You get messages and calls from a person who was not supposed to reach you” | <phone number, public, harassment> |

| Category | Scn. | N | Mean | SD | Experienced | Deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs and alcohol use | 1 | 100 | 3.75 | 0.94 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 93 | 2.74 | 0.85 | 19 | 9 | |

| 3 | 83 | 4.30 | 0.89 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | 144 | 4.34 | 0.66 | 2 | 1 | |

| 5 | 50 | 3.00 | 1.07 | 1 | 0 | |

| 6 | 92 | 3.14 | 0.92 | 5 | 0 | |

| Sex | 7 | 140 | 4.50 | 0.73 | 2 | 1 |

| 8 | 100 | 4.03 | 0.85 | 0 | 0 | |

| 9 | 100 | 3.32 | 1.09 | 4 | 2 | |

| 10 | 96 | 3.44 | 0.93 | 0 | 0 | |

| 11 | 41 | 4.02 | 0.94 | 3 | 2 | |

| 12 | 85 | 3.32 | 0.97 | 3 | 2 | |

| Religion and politics | 13 | 102 | 4.10 | 0.91 | 4 | 1 |

| 14 | 92 | 2.79 | 0.90 | 5 | 1 | |

| 15 | 92 | 2.91 | 1.01 | 4 | 0 | |

| 16 | 95 | 2.78 | 0.92 | 17 | 1 | |

| 17 | 87 | 2.74 | 0.90 | 1 | 1 | |

| 18 | 94 | 4.29 | 0.77 | 1 | 1 | |

| Strong sentiment | 19 | 95 | 3.21 | 0.86 | 12 | 5 |

| 20 | 97 | 3.63 | 0.96 | 4 | 2 | |

| 21 | 89 | 4.22 | 0.73 | 2 | 1 | |

| Location | 22 | 129 | 3.90 | 0.89 | 8 | 4 |

| 23 | 152 | 4.43 | 0.73 | 5 | 3 | |

| Personal identifiers | 24 | 99 | 3.03 | 0.87 | 9 | 8 |

| 25 | 92 | 4.27 | 0.63 | 1 | 0 | |

| 26 | 90 | 2.61 | 0.83 | 20 | 16 |

| Variable | Mean | N | SD | SE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Disclosure | PRE | 3.751 | 281 | 1.480 | 0.088 |

| POS | 3.648 | 281 | 1.560 | 0.093 | |

| Perceived Control | PRE | 4.268 | 281 | 1.483 | 0.088 |

| POS | 4.033 | 281 | 1.558 | 0.093 | |

| Trust in Member | PRE | 3.855 | 281 | 1.205 | 0.072 |

| POS | 3.689 | 281 | 1.251 | 0.075 | |

| Trust in Provider | PRE | 3.532 | 281 | 1.372 | 0.082 |

| POS | 3.409 | 281 | 1.379 | 0.082 | |

| Perceived Risk | PRE | 3.543 | 281 | 0.902 | 0.054 |

| POS | 3.630 | 281 | 0.913 | 0.054 | |

| Pair | Mean diff. | SD | SE | d.f. | t | p | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (PRE-POS) Self-disclosure | 0.103 * | 0.614 | 0.037 | 280 | 3.468 | 0.001 | 0.156 |

| (PRE-POS) Perceived Control | 0.235 * | 0.773 | 0.046 | 280 | 3.468 | 0.001 | 0.304 |

| (PRE-POS) Trust in Member | 0.165 * | 0.553 | 0.033 | 280 | 5.018 | 0.000 | 0.300 |

| (PRE-POS) Trust in Provider | 0.123 * | 0.593 | 0.035 | 280 | 3.468 | 0.001 | 0.207 |

| (PRE-POS) Perceived Risk | −0.093 * | 0.446 | 0.027 | 280 | −3.481 | 0.001 | 0.202 |

| Category | Scn. | N | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | SE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs and alcohol use | 1 | 100 | 2 | 9 | 20 | 50 | 19 | 0.688 | 0.047 |

| 2 | 93 | 5 | 31 | 42 | 13 | 2 | 0.435 | 0.044 | |

| 3 | 83 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 32 | 41 | 0.825 | 0.049 | |

| 4 | 144 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 71 | 62 | 0.835 | 0.027 | |

| 5 | 50 | 4 | 12 | 18 | 12 | 4 | 0.500 | 0.075 | |

| 6 | 92 | 2 | 21 | 37 | 26 | 6 | 0.535 | 0.048 | |

| Sex | 7 | 140 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 50 | 83 | 0.875 | 0.031 |

| 8 | 100 | 0 | 4 | 22 | 41 | 33 | 0.758 | 0.042 | |

| 9 | 100 | 5 | 20 | 26 | 36 | 13 | 0.580 | 0.054 | |

| 10 | 96 | 2 | 11 | 38 | 33 | 12 | 0.609 | 0.047 | |

| 11 | 41 | 0 | 2 | 11 | 12 | 16 | 0.756 | 0.072 | |

| 12 | 85 | 2 | 15 | 31 | 28 | 9 | 0.579 | 0.052 | |

| Religion and politics | 13 | 102 | 1 | 7 | 10 | 47 | 37 | 0.775 | 0.045 |

| 14 | 92 | 6 | 29 | 36 | 20 | 1 | 0.448 | 0.046 | |

| 15 | 92 | 9 | 21 | 34 | 25 | 3 | 0.478 | 0.052 | |

| 16 | 95 | 8 | 27 | 40 | 18 | 2 | 0.445 | 0.047 | |

| 17 | 87 | 8 | 24 | 39 | 15 | 1 | 0.434 | 0.048 | |

| 18 | 94 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 42 | 41 | 0.822 | 0.040 | |

| Strong sentiment | 19 | 95 | 3 | 16 | 36 | 38 | 2 | 0.553 | 0.044 |

| 20 | 97 | 4 | 5 | 30 | 42 | 16 | 0.657 | 0.049 | |

| 21 | 89 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 46 | 33 | 0.806 | 0.039 | |

| Location | 22 | 129 | 1 | 10 | 22 | 64 | 32 | 0.725 | 0.039 |

| 23 | 152 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 60 | 81 | 0.857 | 0.030 | |

| Personal identifiers | 24 | 99 | 2 | 26 | 42 | 25 | 4 | 0.508 | 0.044 |

| 25 | 92 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 52 | 33 | 0.818 | 0.033 | |

| 26 | 90 | 7 | 33 | 39 | 10 | 1 | 0.403 | 0.044 |

Scenarios with risk index higher than 0.5.

Scenarios with risk index higher than 0.5.© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Díaz Ferreyra, N.E.; Kroll, T.; Aïmeur, E.; Stieglitz, S.; Heisel, M. Preventative Nudges: Introducing Risk Cues for Supporting Online Self-Disclosure Decisions. Information 2020, 11, 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11080399

Díaz Ferreyra NE, Kroll T, Aïmeur E, Stieglitz S, Heisel M. Preventative Nudges: Introducing Risk Cues for Supporting Online Self-Disclosure Decisions. Information. 2020; 11(8):399. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11080399

Chicago/Turabian StyleDíaz Ferreyra, Nicolás E., Tobias Kroll, Esma Aïmeur, Stefan Stieglitz, and Maritta Heisel. 2020. "Preventative Nudges: Introducing Risk Cues for Supporting Online Self-Disclosure Decisions" Information 11, no. 8: 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11080399

APA StyleDíaz Ferreyra, N. E., Kroll, T., Aïmeur, E., Stieglitz, S., & Heisel, M. (2020). Preventative Nudges: Introducing Risk Cues for Supporting Online Self-Disclosure Decisions. Information, 11(8), 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11080399