Breaking the Chains of Open Innovation: Post-Blockchain and the Case of Sensorica

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Open Innovation: From a Strategic Option to a New Innovation Paradigm

2.2. Blockchain Technology: Reworking Value

2.3. Resources–Events–Agents: A Post-Blockchain Accounting Model

- Limited dimensions: Double-entry elements almost exclusively express monetary representations. This does not allow for representations of other valuable, multidimensional data, such as productivity, performance, and reliability;

- Not (always) appropriate classification schemes: The categories used to represent the information related to the economic affairs of an enterprise are limited to accounting objects. This often omits data that do not fit these categories, while it organizes data in ways that are of little use to non-accountants;

- High-level aggregation for stored information: The aggregation of accounting data takes place on a level that only informs executive decision-making and the relevant information concerning economic activities is not available in a primary form to be aggregated on a different level, where different forms, quantities, and foci are needed to serve other functions;

- Restricted degree of integration with other functional areas of the enterprise: Accounting data concern representations of various phenomena, which are often separately documented by non-accountants in different forms. This leads to inconsistencies, overlaps, and information gaps.

3. Materials and Methods

4. The Case of Sensorica

4.1. General Overview

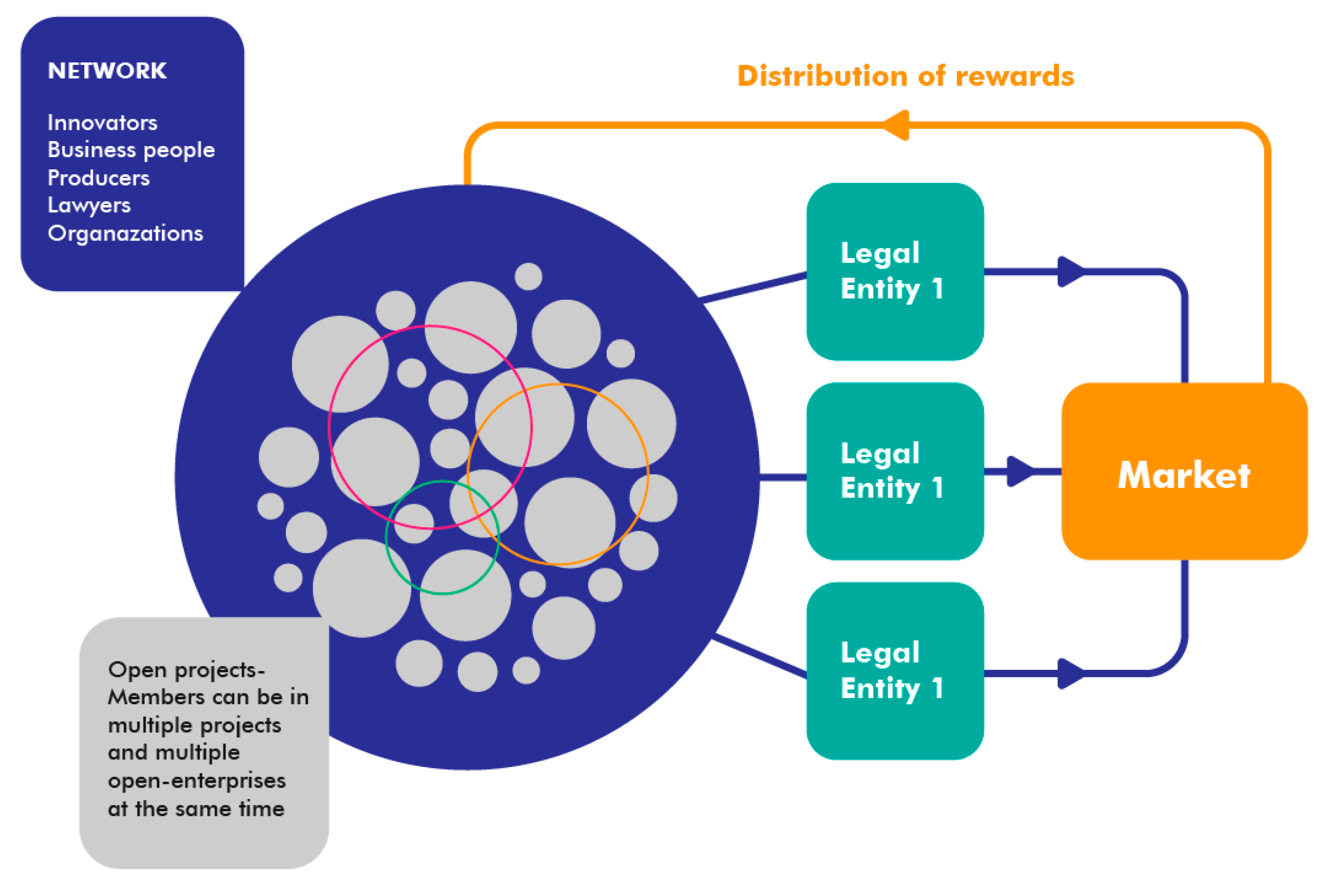

4.2. Organization: The Open Value Network

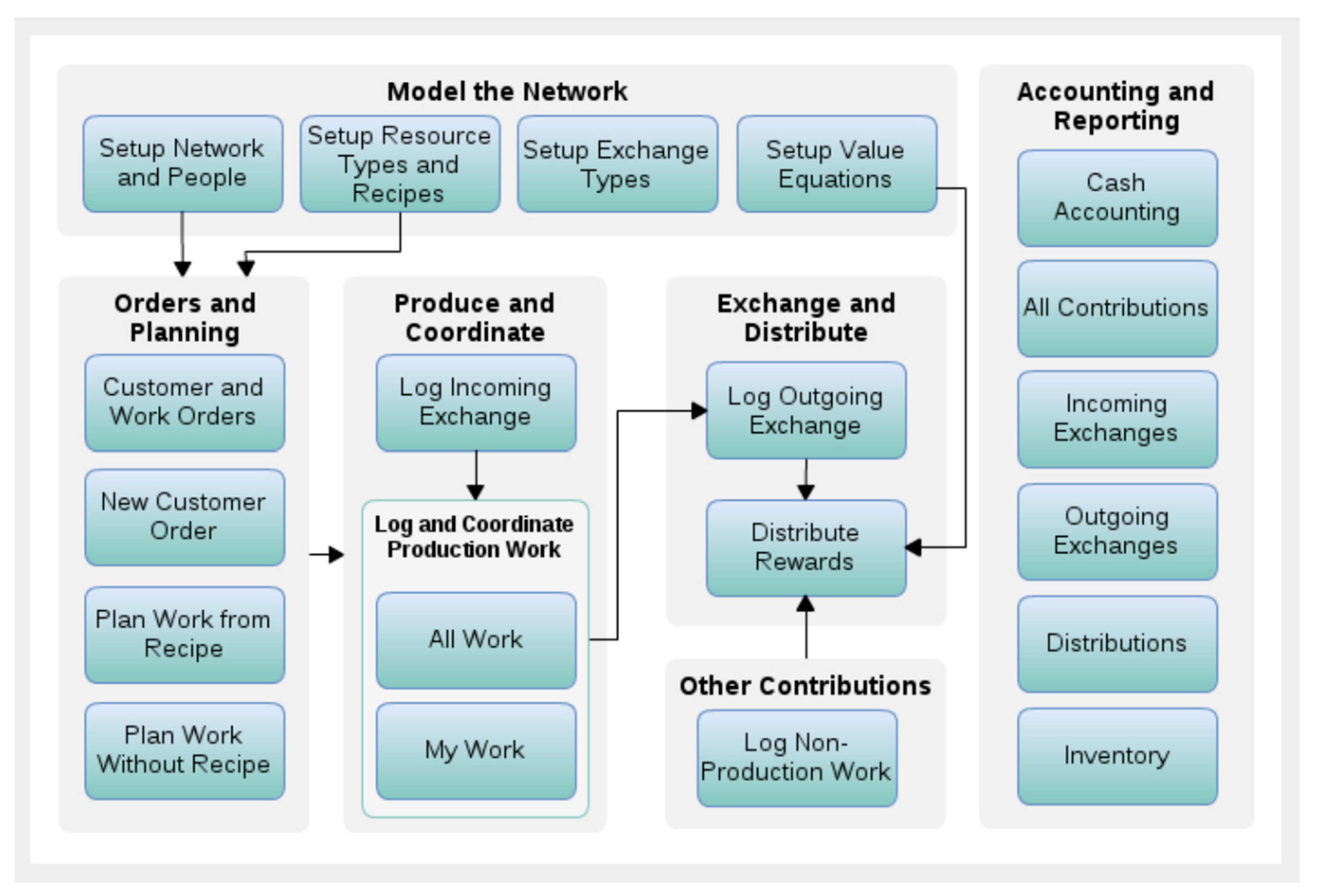

4.3. Technological Infrastructure: Contributory Accounting and Network Resource Planning

4.4. Projects and Operation

- Project idea: People begin broadcasting an informal proposal in the Sensorica forum or through other media. The rationale and main idea are discussed and explored;

- Building capacity and communication strategy: The project participants agree on the procedures for project execution and the appropriate communication channels and coordination tools;

- Establishing project structure: A minimum working structure is developed, comprising, at least, the description of the project’s (a) governance, including the rules of conduct, conflict management, and distribution of rewards; (b) roadmap, including important milestones and plans; and (c) custodian agreement, signed by the custodian to administer the relevant funds;

- Creation of a core team: After the conditions for communication and structure have been agreed upon, a core team of instigators is formed and they reach out to the network to map interest, gather feedback, and create incentives for participation;

- Establishing incentive structure: A structure is developed to motivate potential contributors, including a market plan and a plan of the necessary resources, including skills, equipment, materials, and financial resources;

- Expanding the team: Once the incentive structure is set, a process of outreach, onboarding and engagement, and information mining begins to attract the necessary talent and resources;

- Planning activities: The activities needed for the project implementation are systematized and formalized in the NRP-CAS using “workflow recipes” [68], i.e., a set of pre-defined descriptions for a series of processes and distributions of tasks;

- Documentation: All activities in Sensorica are followed by extensive documentation in the project website, as well as in a main shared document, which functions as an index for various working documents concerning major components.

5. Discussion

5.1. On the Viability of the OVN Model

5.2. Breaking the Chains: From Chains to Ecosystems

5.3. Beyond Innovation, towards a Better Life: A Human-Centric Technological Trajectory

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morris, W. News from Nowhere: An Epoch of Rest, Being Some Chapters from a Utopian Romance; Longmans Green and Co: London, UK, 1891. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, J. Crowdsourcing: Why the Power of the Crowd Is Driving the Future of Business; Three Rivers Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Benkler, Y. The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Benkler, Y. Peer production, the commons and the future of the firm. Strateg. Organ. 2017, 15, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gilson, R.J.; Sabel, C.F.; Scott, R.E. Contracting for innovation: Vertical disintegration and interfirm collaboration. Columbia Law Rev. 2009, 109, 431–502. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhani, K.R.; Lifshitz-Assaf, H.; Tushman, M.L. Open innovation and firm boundaries: Task decomposition, knowledge distribution and the locus of innovation. In Handbook of Economic Organization: Integrating Economic and Organization Theory; Grandori, A., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 355–382. [Google Scholar]

- Karo, E.; Kattel, R. Should “open innovation” change innovation policy thinking in catching-up economies? Considerations for policy analyses. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2011, 24, 173–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Open Business Models: How to Thrive in the New Innovation Landscape; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. Open innovation: A new paradigm for understanding industrial innovation. In Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm; Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., West, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlander, L.; Gann, D.M. How open is innovation? Res. Policy 2010, 39, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.J.; Cohen, W.M. Information flow in research and development laboratories. Adm. Sci. Q. 1969, 14, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Res. Policy 1986, 15, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, P.; Hartmann, D.A.P. Why ‘open innovation’ is old wine in new bottles. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2009, 13, 715–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Appleyard, M. Open innovation and strategy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2007, 50, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunswicker, S.; Chesbrough, H. The adoption of open innovation in large firms. Res. Technol. Manag. 2018, 61, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vrande, V.; De Jong, J.P.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; De Rochemont, M. Open innovation in SMEs: Trends, motives and management challenges. Technovation 2009, 29, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meer, H. Open Innovation–The Dutch Treat: Challenges in Thinking in Business Models. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2007, 16, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A.J. The paradox of openness: Appropriability, external search and collaboration. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Hippel, E. The Sources of Innovation; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Von Hippel, E. Free Innovation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Harhoff, D.; Lakhani, K.R. Revolutionising Innovation: Users, Communities, and Open Innovation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Coriat, B. From Exclusive IPR Innovation Regimes to “Commons- Based” Innovation Regimes Issues and Perspectives. In Proceedings of the Role of the State in the XXI century ENAP, Brasilia, Brazil, 3–4 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson, A.; Bauwens, M.; Peitersen, N. The crisis of value and the ethical economy. J. Futures Stud. 2008, 12, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bauwens, M.; Kostakis, V.; Pazaitis, A. Peer to Peer: The Commons Manifesto; Westminster University Press: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Benkler, Y. Coase’s Penguin, or, Linux and The Nature of the Firm. Yale Law J. 2002, 112, 369–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostakis, V. How to Reap the Benefits of the “Digital Revolution”? Modularity and the Commons. Handuskultur 2019, 20, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tsaliki, P.V. Marx on entrepreneurship: A note. Int. Rev. Econ. 2006, 53, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippi, P.; Wright, A. Blockchain and the Law: The Rule of Code; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lansiti, M.; Lakhani, K.R. The truth about blockchain. Harvard Bus. Rev. 2017, 95, 118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Casino, F.; Dasaklis, T.K.; Patsakis, C. A systematic literature review of blockchain-based applications: Current status, classification and open issues. Telemat. Inf. 2019, 36, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackius, N.; Petersen, M. Blockchain in Logistics and Supply Chain: Trick or Treat? In Digitalization in Supply Chain Management and Logistics; Kersten, W., Blecker, T., Ringle, C.M., Eds.; Epubli GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pazaitis, A.; De Filippi, P.; Kostakis, V. Blockchain and value systems in the sharing economy: The illustrative case of Backfeed. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2017, 125, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, R. From Private Ownership Accounting to Commons Accounting. Available online: http://commonstransition.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/AccountingForPlanetarySurvival_defx-2.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Bauwens, M.; Pazaitis, A. P2P Accounting for Planetary Survival. Available online: http://commonstransition.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/AccountingForPlanetarySurvival_defx-2.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- McCarthy, W.E. Construction and use of integrated accounting systems with entity-relationship modeling. In Entity-Relationship Approach to Systems Analysis and Design; Chen, P., Ed.; North Holland Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1980; pp. 625–637. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, W.E. The REA accounting model: A generalized framework for accounting systems in a shared data environment. Acc. Rev. 1982, 57, 554–578. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, C.; Gerard, G.J.; Grabski, S.V. Resources-events-agents design theory: A revolutionary approach to enterprise system design. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2016, 38, 554–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, R.; McCarthy, W.E. REA: A semantic model for internet supply chain collaboration. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Object-Oriented Programming, Systems, Languages, and Applications, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 21 January 2000; Available online: http://jeffsutherland.org/oopsla2000/mccarthy/mccarthy.htm (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- O’Leary, D.E. On the relationship between REA and SAP. Int. J. Acc. Inf. Syst. 2004, 5, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, R.; Polovina, S. REA analysis of SAP HCM; some initial findings. In Proceedings of the 3rd Cubist Workshop, Dresden, Germany, 22 May 2013; pp. 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbossche, P.E.A.; Wortmann, J.C. Why accounting data models from research are not incorporated in ERP systems. In Proceedings of the 2nd International REA Technology Workshop, Santorini Island, Greece, 25 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Competition, cooperation and innovation: Organisational arrangements for regimes of rapid technological progress. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1992, 18, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, W.E. The REA modeling approach to teaching accounting information systems. Issues Acc. Educ. 2003, 18, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allee, V. Value network analysis and value conversion of tangible and intangible assets. J. Intell. Cap. 2008, 9, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. Case studies. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 236–247. [Google Scholar]

- Palys, T.; Atchison, C. Research Decisions: Quantitative and Qualitative Perspectives; Thomson Nelson: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Murthy, D. Digital ethnography: An examination of the use of new technologies for social research. Sociology 2008, 42, 837–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostakis, V. Identifying and understanding the problems of Wikipedia’s peer governance: The case of inclusionists versus deletionists. First Monday 2010, 15. Available online: https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/rt/printerFriendly/2613/2479Understanding (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Interfaces Between Open Networks and Classical Institutions: The Sensorica Experience. Available online: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1ABmC6YJsszlIPoL-YXU3GF-PLHY0tmQdocBExswh7Lw/edit#heading=h.xqwod5fqadz2 (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Governance. Available online: https://www.sensorica.co/governance (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Open Value Network: A Framework for Many-to-Many Innovation. Available online: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1iwQz5SSw2Bsi_T41018E3TkPD-guRCAhAeP9xMdS2fI/pub#h.pkzfosme7qaf (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Legal Structure. Available online: http://valuenetwork.referata.com/wiki/Legal_structure (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Value Reputation Roles. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/sensoricahome/home/working-space/value-reputation-roles (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Reputation System. Available online: http://valuenetwork.referata.com/wiki/Reputation_system (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Role System. Available online: http://valuenetwork.referata.com/wiki/Role_system (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Value Accounting System. Available online: http://valuenetwork.referata.com/wiki/Value_accounting_system (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Fluid equity. Available online: http://valuenetwork.referata.com/wiki/Fluid_equity (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Why Do We Need a Contribution Accounting System? Available online: http://multitudeproject.blogspot.com/2014/01/why-do-we-need-value-accounting-system.html (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Concepts. Available online: https://github.com/valnet/valuenetwork/wiki/Concepts (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Everything in NRP Is Connected to Everything Else. Available online: https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1cMDVLAfV6JLBZA-0kHmKcAWfsm68AL6mPQMvrVKGyVA/edit#slide=id.g18add4e6c2_0_341 (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Procedure for Kickstarting Projects. Available online: https://docs.google.com/document/d/14CcrovAFdeK5c-PGi9MANk_fdYjqV1WDf8Gy4Rg_6FE/pub (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- How to Create a New Project Using the New Site. Available online: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1ehuG8UKjAA2XOgP50INwZ4-bXUA1v_-hWk3VBLOpiOw/edit#heading=h.psr7ahgkbxx0 (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Endogenous Project Stewardship Methodology. Available online: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1nMrdwysCPKlk6ixc_zqHtaa2G1_7Ym1DC39OdOfXsDg/edit#heading=h.x13a0vmsgw4y (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Recipe. Available online: http://valuenetwork.referata.com/wiki/Recipe#Workflow_recipe (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Contributions for Project Sensor Network. Available online: http://nrp.sensorica.co/accounting/contributions/352 (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Project: Sensor Network Project. Available online: http://nrp.sensorica.co/accounting/agent/352 (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Value and Governance Equation for Sensor Network Project. Available online: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1ezjVX4-tWY8ptOIyjGzpw_0xGqNgCW3aH5q-7nxLHrw/edit#gid=162995459 (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Revenue and Funding. Available online: https://www.sensorica.co/network-admin/revenue-and-funding (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Dashboard. Available online: https://www.sensorica.co/network-admin/dashboard#h.p_RWJ2mwKDVMcA (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- NRP-VAS. Available online: http://valuenetwork.referata.com/wiki/NRP-VAS (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Freedomcoop Tools: OCP & Alternative Banking. Available online: http://freedomcoop.eu/tools (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- About OCE. Available online: https://github.com/opencooperativeecosystem/docs (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- ValueFlows. Available online: https://valueflo.ws (accessed on 30 January 2020).

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pazaitis, A. Breaking the Chains of Open Innovation: Post-Blockchain and the Case of Sensorica. Information 2020, 11, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11020104

Pazaitis A. Breaking the Chains of Open Innovation: Post-Blockchain and the Case of Sensorica. Information. 2020; 11(2):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11020104

Chicago/Turabian StylePazaitis, Alex. 2020. "Breaking the Chains of Open Innovation: Post-Blockchain and the Case of Sensorica" Information 11, no. 2: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11020104

APA StylePazaitis, A. (2020). Breaking the Chains of Open Innovation: Post-Blockchain and the Case of Sensorica. Information, 11(2), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11020104