Forestland Resource Exploitation Challenges and Opportunities in the Campo Ma’an Landscape, Cameroon

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

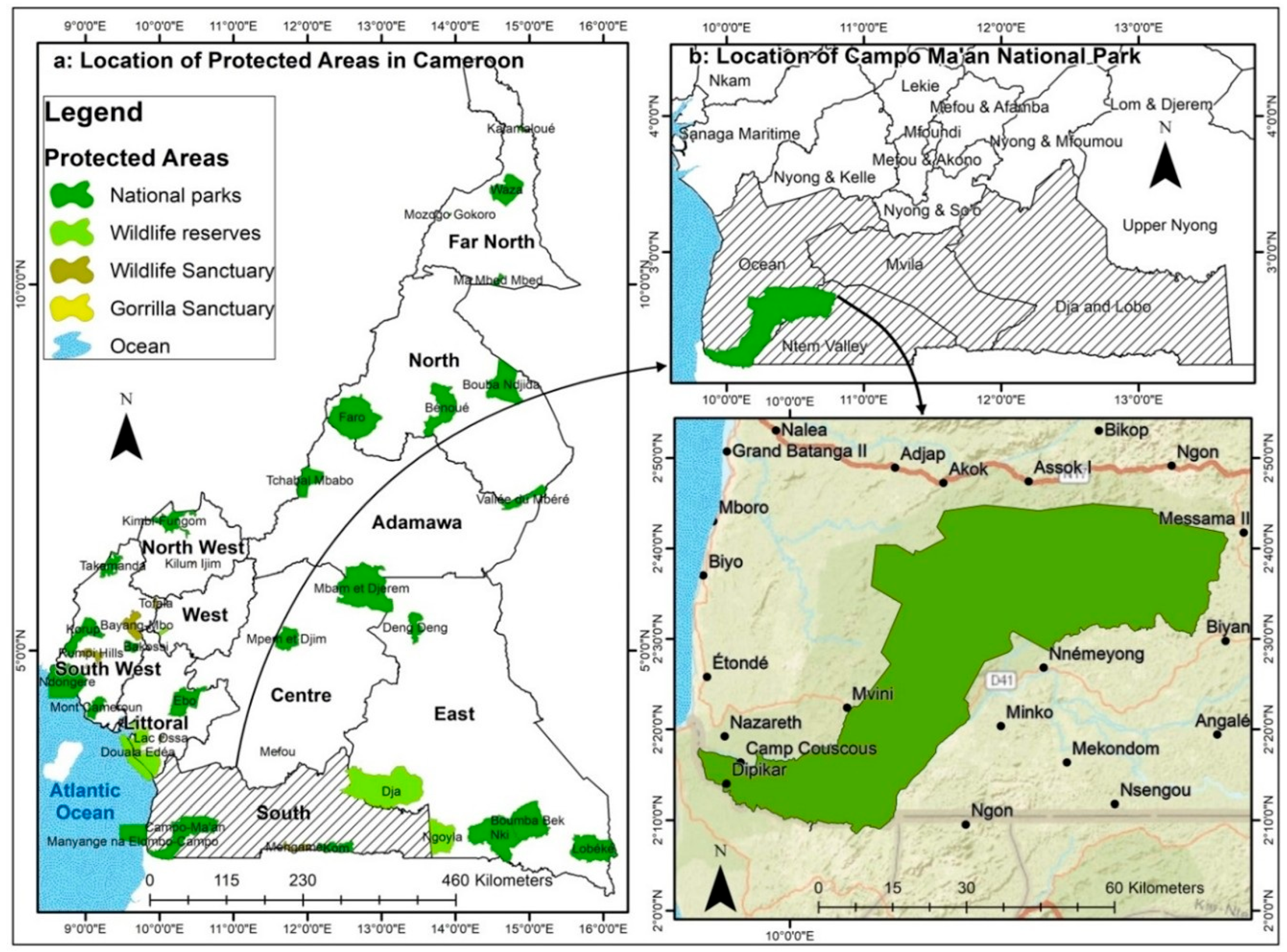

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Survey and Sampling

2.3. Data Treatment and Analysis

- P: Probability that Natural Resource Exploitation is affected by challenges.

- 1 − P: Probability that Natural Resource Exploitation is not affected by challenges.

- X1, X1…, Xn: Different predictor/explanatory variables.

3. Results

3.1. Challenges Involved in Forest Resource Exploitation Around the CMNP

3.1.1. Socio-Cultural Challenges

“The park has long existed since 1932. Before the coming of the park, our parents lived well until the road came and divided the village, brought development, and the conflict between man against animal and people became uncomfortable. Many young people left for the city, each one being afraid”.

3.1.2. Economic Challenges

3.1.3. Technical Challenges

3.1.4. Institutional Challenges

3.2. Challenges Linked to Land Resource Exploitation in the Campo Ma’an National Park

3.2.1. Socio-Cultural Challenges

3.2.2. Economic Challenges

3.2.3. Technical Challenges

3.2.4. Institutional Challenges

3.3. Forest Resources Opportunities Around the Campo Ma’an National Park

3.4. Opportunities in Land Resources Exploitation Around the Campo Ma’an National Park

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Challenges in Forest Resources Exploitation in the Campo Ma’an National Park Communities

4.2. Challenges in Land Resources Exploitation in the Campo Ma’an National Park

4.3. Opportunities in Forest Resources Exploitation in the Campo Ma’an National Park

4.4. Opportunities in Land Resources Exploitation in the Campo Ma’an National Park

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). The Sustainable Use of Natural Resources: The Governance Challenge; Still Only One Earth: Lessons from 50 years of UN sustainable development policy Brief #16; IISD: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.E. Resource Exploitation and Environmental Degradation. 2025. Available online: https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/environmental-sciences/resource-exploitation-and-environmental-degradation (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Gupta, G.; Kumar, R.; Singh, K.; Rawat, V.; Lavania, P.; Kumari, P.; Rani, M.; Dobriyal, M.; Srivastav, M.; Kumar, P. Chapter 4—Forest resources: Sustainable exploitation and management. In Earth Observation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2026; pp. 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Inoue, M.; Shivakoti, G.P.; Sharma, S. Chapter 1. Managing natural resources in Asia: Challenges and approaches. In Natural Resource Governance in Asia. from Collective Action to Resilience Thinking; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). The World Needs Forests. Germany’s Forest Action Plan for Sustainable Development; Division 122: Rural Development; Land rights; Forests: Berlin, Germany, 2017.

- World Bank. The Natural Resource Degradation and Vulnerability Nexus: An Evaluation of the World Bank’s Support for Sustainable and Inclusive Natural Resource Management (2009–2019); World Bank Independent Evaluation Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kimengsi, J.N.; Lambi, C.M. Reflections on the natural-resource development paradox in the Bakassi Area (Ndian Division) of Cameroon. J. Afr. Stud. Dev. 2015, 7, 239–249. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, F.; Allison, E. Livelihood Diversification and Natural Resources Access; Livelihood support programme (LSP), Working paper 9; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Wang, E.; Mao, X.; Benjamin, W.; Liu, Y. Sustainable poverty alleviation through forests: Pathways and strategies. Sustainable poverty alleviation through forests: Pathways and strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 167336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimengsi, J.N.; Nkongwibuen, A.L.; Assako, R.A.; Tume, S.J.P.; Yemmafouo, A.; Mairomi, H.W. Hollow Frontier Dynamics and Land Resource Exploitation in the Mungo Landscape of Cameroon. Can. J. Trop. Geogr. 2023, 9, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Norfolk, S. Examining Access to Natural Resources and Linkages to Sustainable Livelihoods: A Case Study of Mozambique; LSP working paper 17; Food and Agricultural organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Natural Resources and Pro-Poor Growth: The Economics and Politics; OECD: Paris, France, 2008; ISBN 978-092-64-04182-0. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the world 2018. Building Climate Resilience for Food Security and Nutrition; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. The Economic Significance of Natural Resources: Key Points for Reformers in Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia; Environmental Performance and Information Division; Environment Directorate: Paris, France, 2011; pp. 1–42.

- Kimengsi, J.N.; Pretzsch, J.; Kechia, M.A.; Ongolo, S. Measuring Livelihood Diversification and Forest Conservation Choices: Insights from Rural Cameroon. Forests 2019, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. Recognizing the Importance of Scotland’s Natural Capital; PPDAS1297902 (06/23); APS Group: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2021.

- Nkembi, L.; Nkengafac, N.; Forghab, N.E. Assessment of livelihood activities for conservation in the Deng Deng National Park-Belabo council Forest conservation corridor, East Region of Cameroon. Int. J. Life Sci. Arch. 2022, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewane, E.B.; Olome, E.B.; Lee, H.-H. Challenges to Sustainable Forest Management and Community Livelihoods Sustenance in Cameroon: Evidence from the Southern Bakundu Forest Reserve in Southwest Cameroon. J. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RKometa, N.; Kimengsi, J.N.; Wanie, C.M. Dynamics of Communicable and Non-Communicable Health Shocks in the Campo Ma’an National Park: Implications on Natural Resources Dependent Livelihoods. J. Geogr. Environ. Earth Sci. Int. 2025, 29, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuuwill, A.; Kimengsi, J.N.; Campion, B.B. Pandemic-induced shocks and shifts in forest-based livelihood strategies: Learning from COVID-19in the Bia West District of Ghana. Environ. Res. Lett 2022, 17, 064033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Vernick, T.; Rupp, S. Death does not come from the forest but from the village. People, great apes, and disease in the Equatorial African rain forest. Dans Cah. D’anthropologie Soc. 2012, 8, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amawa, S.G.; Atiekum, Z.E.; JKimengsi, N.; Sunjo, T.E. Water Resources Exploitation Practices and Challenges: The Case of River Meme, Cameroon. International 2020, 24, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kimengsi, J.N.; Owusu, R.; Djenontin, I.N.S. What Do we (Not) Know on Forest Management institutions in Sub-saharan Africa? A regional Comparative Review. Land Use Policy 2022, 14, 105931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMNP. Management Plan of the Campo Ma’an National Park and Its Periphery 2015–2019 Period; Campo Ma’an National Park: Océan, Cameroon, 2014; pp. 1–139. [Google Scholar]

- NIC. Cameroon—Subnational Administrative Boundaries. Cameroon Administrative Level 0-3 Boundaries (COD-AD) Dataset Version 01. Ocha Field Information Section (FISS). 2000. Available online: https://data.humdata.org/dataset/cod-ab-cmr (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- UNEP-WCMC; IUCN. World Database on Protected Areas. 2024 Report on Worlds Protected and Conserved Areas. Available online: https://www.protectedplanet.net/en/thematic-areas/wdpa?tab=WDPA (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Jaza, F.; Tsafack, P.P.; Kamajou, F. Logit model of analysing the factors affecting the adoption of goat raising activity by farmers in the non-pastoral centre region of Cameroon. Tropicultura 2018, 36, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Girma, W.; Beyene, F. Institutional Challenges in Sustainable Forest Management: Evidence from the Gambella Regional State of Western Ethiopia. J. Sustain. For. 2015, 34, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SDSN; IEEP. The 2020 Europe Sustainable Development Report: Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic; Sustainable Development Solutions Network and Institute for European Environmental Policy: Paris, France; Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kazungu, M.; Zhunusova, E.; Yang, A.L.; Kabwe, G.; Gumbo, D.; Gunter, S. Forest use strategies and their determinants among rural households in the Miombo Wood-lands of the Copperbelt Province, Zambia. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 111, 102078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Do, M.H.; Nguyen, D.L.; Grote, U. Shocks, agricultural productivity, and natural resource extraction in rural Southeast Asia. World Dev. J. 2022, 159, 106043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, R.C. Resource Management in Asia; EBSCO: Ipswich, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2000; Lessons from the past 50 years no. 32; FAO Agriculture Series Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2000; ISSN 008 I-4539. [Google Scholar]

- Attah, A.N. Second Assessment of the Impact of COVID-19 on Forests and Forest Sector in the African Region. Challenges, strategies, recovery measures and best practice for reducing impact of COVID-19 on forests and the forest sector, Africa Region Report. In Proceedings of the 17th Session of the United Nations Forum on Forests, New York, NY, USA, 9–13 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Forests: Facing the Challenges of Global Change; Mediterra: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mathys, E.; Murphy, E.; Woldt, M. USAID Office of Food for Peace Food Security Desk Review for Mali; FY2015–FY2019; FHI 360/FANTA: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Beckline, M.; Manan, A.; Dominic, N.; Mukete, N.; Hu, Y. Patterns and Challenges of Forest Resources Conservation in Cameroon. Open Acess Libr. J. 2022, 9, e8683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordi, L.; Jojanna, L.; Silje, F.; Sanna, N. COVID-19 Related Job Demands and Resources, Organizational Support and Employment Well-Being: A Study of Two Nordic Countries. Chall. J. Planet. Health 2021, 13, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Salvia, R.; Quaranta, V.; Sateriano, A.; Quaranta, G. Land Resource Depletion, Regional Disparities, and the Claim for a Renewed ‘Sustainability Thinking’ under Early Desertification Conditions. Resources 2022, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-habitat). Land and Natural Resource Tenure in Selected Countries of Eastern and Southern Africa; UN–Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). A Forest of Opportunities: Living and Working Conditions in Argentina’s Forestry Sector; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Inoni, O.E. Effects of forest resources exploitation on the economic well-being of rural households in delta state, Nigeria. Agric. Trop. et Subtrop. 2009, 42, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. The Global Risks Report 2022, 17th ed.; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report-2022/ (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- ELD Initiative. The Value of Land: Prosperous Lands and Positive Rewards Through Sustainable Land Management; ELD Initiative: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Available online: www.eld-initiative.org (accessed on 12 December 2025).

| Selected Communities | Estimated Population per Community | Total Number of Households | Sampled Households | Effective Responses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ebodje | 1018 | 60 | 31 | 30 | |

| Campo Beach | 735 | 71 | 37 | 36 | |

| Mvini/Akak | 336 | 24 | 12 | 12 | |

| Nkoelon | 104 | 28 | 14 | 14 | |

| Mabiogo | 159 | 19 | 10 | 10 | |

| Ebianemeyong | 181 | 25 | 13 | 13 | |

| Nkwadjap | 284 | 23 | 12 | 12 | |

| Nazareth | 83 | 7 | 4 | 4 | |

| Niete(Nyamabande/Ngock) | 144 | 30 | 16 | 16 | |

| Melen (Ma’an) | 131 | 17 | 9 | 8 | |

| Ndageng (Akom II) | 1230 | 81 | 42 | 40 | |

| Totals | 11 villages | 4405 | 385 | 200 | 195 |

| (a) Omnibus Tests of Model Coefficients | ||||

| Chi-square | Df | Sig. | ||

| Step 1 | Step | 36.849 | 11 | 0.000 |

| Block | 36.849 | 11 | 0.000 | |

| Model | 36.849 | 11 | 0.000 | |

| (b) Model Summary | ||||

| Step | −2 Log likelihood | Cox and Snell R Square | Nagelkerke R Square | |

| 1 | 217.055 a | 0.177 | 0.240 | |

| Driver | Beta (B) | S. E | p-Value | Exp (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical challenges of forest resources exploitation | −0.197 | 0.140 | 0.159 | 0.821 |

| Economic challenges of forest resources exploitation | −0.389 | 0.151 | 0.010 | 0.678 |

| Institutional challenges of forest resources exploitation | 0.296 | 0.217 | 0.173 | 1.345 |

| Socio-demographic challenges of forest resources exploitation | −0.003 | 0.131 | 0.982 | 0.997 |

| Technical challenges of land resources exploitation | 0.148 | 0.190 | 0.436 | 1.160 |

| Economic challenges of land resources exploitation | 0.423 | 0.153 | 0.006 | 1.527 |

| Institutional challenges of land resources exploitation | 0.162 | 0.165 | 0.326 | 1.176 |

| Socio-demographic challenges of land resources exploitation | −0.121 | 0.132 | 0.359 | 0.886 |

| Challenges of Forest Resources Exploitation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical | Technological challenges | Low technical capacity | Limited training in participatory planning | Limited forest research | Unsustainable forest management | ||

| 22.2 | 30.9 | 17.5 | 11.9 | 12.9 | |||

| Economic | Market power | Economic Transition | Poor Living standards | Low per capita income | Unemployment | Economic Deprivation | Inadequate forest Funding |

| 11.9 | 21.1 | 37.1 | 19.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 3.1 | |

| Institutional | Elite Capture | Lack of forest strategy | Institutional failures | Foreign donor dependence | |||

| 12.9 | 46.4 | 33.0 | 5.7 | ||||

| Socio-cultural | Demographic increase | Human–Wildlife conflicts | Physical and mental health | Inaccessibility | Poor infrastructure | Cultural limitation | |

| 16.5 | 53.6 | 17.5 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 2.6 | ||

| Challenges of Land Resources Exploitation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical | Technological challenges | Low technical capacity | Limited training in participatory planning | Limited agricultural research | Unsustainable Land Management | ||

| 10.8 | 16.5 | 55.2 | 12.4 | 3.1 | |||

| Economic | Market power | Economic Transition | Poor Living standards | Low per Capita income | Unemployment | Economic deprivation | Inadequate land related funding |

| 14.9 | 34.5 | 31.4 | 9.3 | 2.1 | 3.1 | ||

| Institutional | Elite capture | Human–Wildlife conflict | Institutional Failures | Power and conviction on land resources | |||

| 14.4 | 39.7 | 22.7 | 14.4 | ||||

| Socio-cultural | Demographic increase | Human–Wildlife conflict | physical and mental health issues | Inaccessibility | Increase consumption | Limited infrastructure | |

| 10.3 | 24.2 | 45.4 | 7.2 | 5.2 | 3.1 | ||

| Opportunities in Forestland Resources Exploitation in the Campo Ma’an National Park Communities | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Opportunities in forest resources | % | Opportunities in forest resources | % |

| NTFP domestication | 5.7 | Land use diversification | 13.9 |

| Energy potentials | 24.7 | Agricultural development | 23.2 |

| Processing and storage of medicinal plants | 14.4 | Economic growth | 31.4 |

| Ecotourism | 35.6 | Sustainable practices | 27.8 |

| Biodiversity conservation through indigenous knowledge | 7.2 | Land rights | 3.6 |

| Carbon sequestration | 4.1 | ||

| Sustainable wood products and materials (Timber) | 6.2 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kometa, R.N.; Forba, C.F.; Mvo, W.C.; Kimengsi, J.N. Forestland Resource Exploitation Challenges and Opportunities in the Campo Ma’an Landscape, Cameroon. Challenges 2026, 17, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe17010002

Kometa RN, Forba CF, Mvo WC, Kimengsi JN. Forestland Resource Exploitation Challenges and Opportunities in the Campo Ma’an Landscape, Cameroon. Challenges. 2026; 17(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe17010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleKometa, Raoul Ndikebeng, Cletus Fru Forba, Wanie Clarkson Mvo, and Jude Ndzifon Kimengsi. 2026. "Forestland Resource Exploitation Challenges and Opportunities in the Campo Ma’an Landscape, Cameroon" Challenges 17, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe17010002

APA StyleKometa, R. N., Forba, C. F., Mvo, W. C., & Kimengsi, J. N. (2026). Forestland Resource Exploitation Challenges and Opportunities in the Campo Ma’an Landscape, Cameroon. Challenges, 17(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe17010002