How Transformative Experiences Reshape Values, Worldviews, and Engagement with Sustainability: An Integral Inquiry

Abstract

1. Introduction

What makes it difficult is that the ego prefers to satisfy itself, rather than satisfy the greater good. That’s just the way we tend to be built, until we have a transformative experience… a change of mind, a change of heart that switches you from one way of looking at things to another.[17] (25:30)

1.1. Definition of Concepts and Terms

- Factors

- Integration

- Sustainability

- Social Change

- Transformation

1.2. Literature Review: Inner and Outer Change

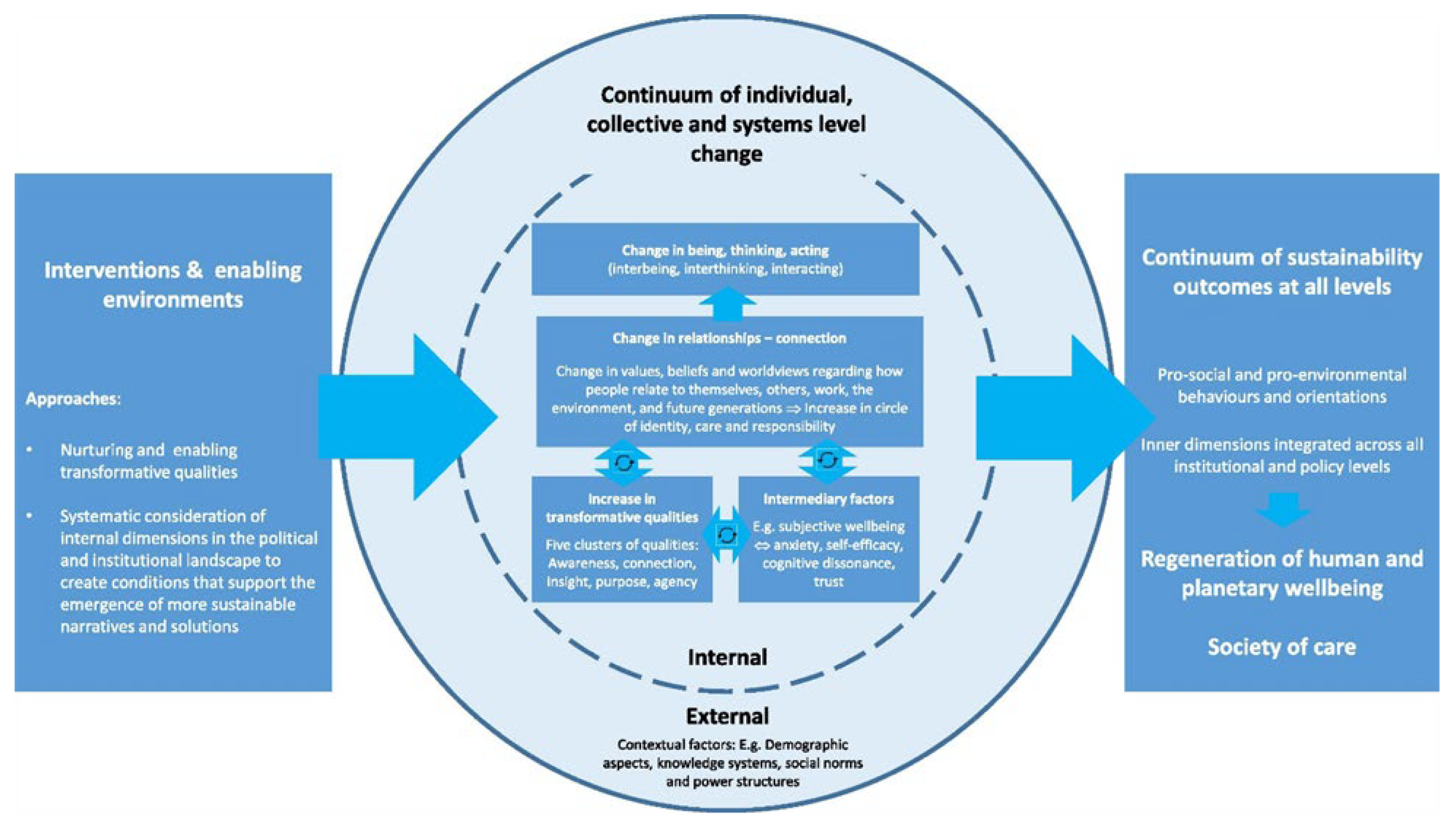

Despite the extensive body of research on personal/adult development, the application of its findings to sustainability and climate change is in its early stages. This is hampering current progress. It is, therefore, essential to address current limitations, and bridge the gap between work that focuses on sustainability…and internal dimensions… This requires a comprehensive understanding of internal–external transformation toward sustainability, which is currently lacking.(p. 8)

What is the nature of the relationship between a transformative life experience and engagement with activities focused upon sustainability?

2. Materials and Methods

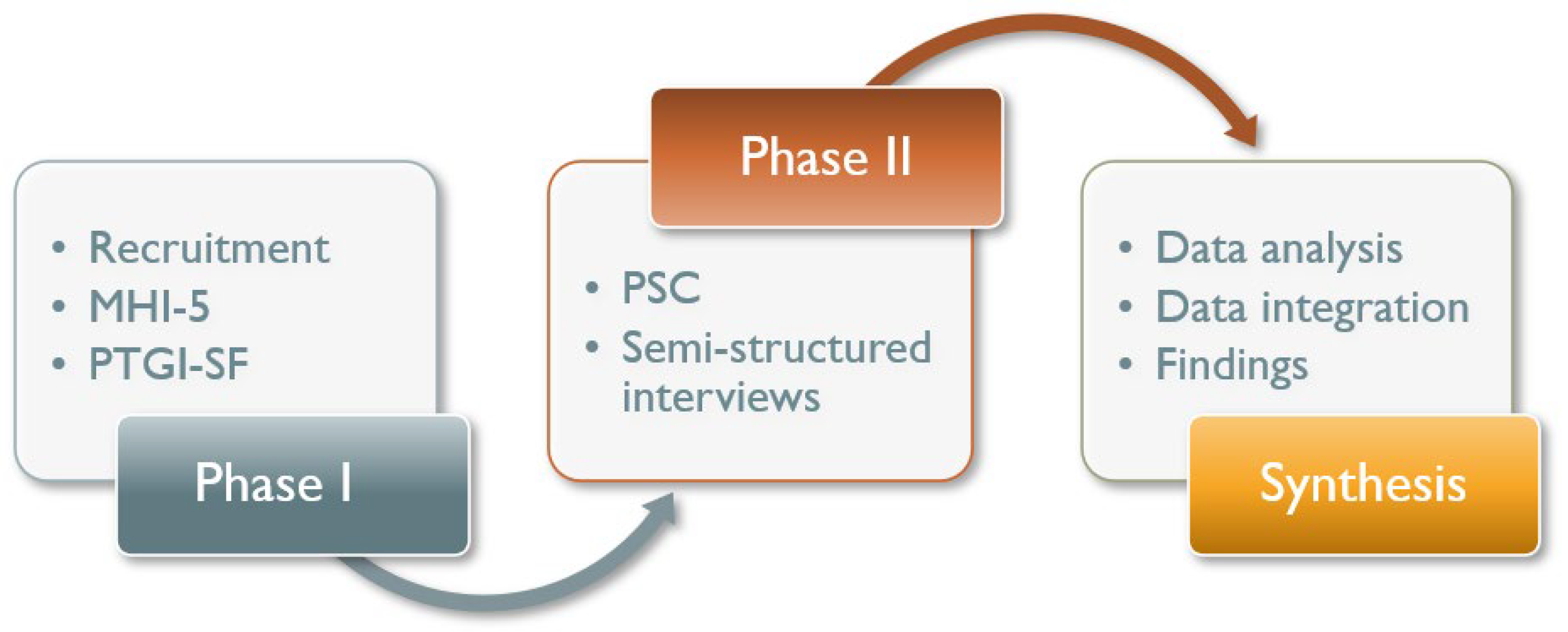

2.1. Structure

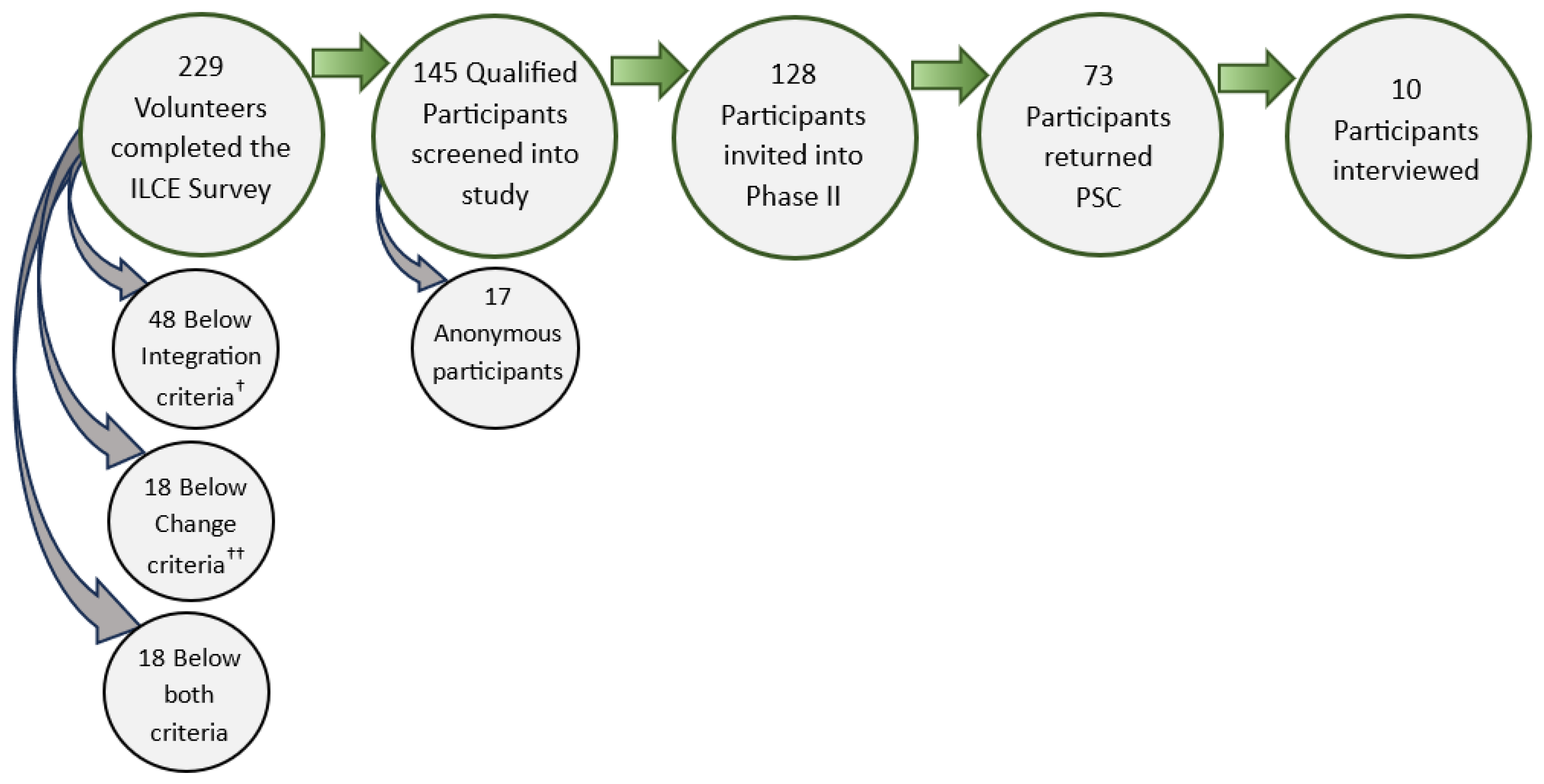

2.2. Phase I: Quantitative

Participants, Ethics, Procedures, and Analysis

2.3. Phase II: Qualitative

Analysis

2.4. Integration

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative

3.2. Qualitative

3.2.1. Theme 1: Defining Social Change

[I now] work for a business that I co-own with a very small number of others, and … we have a very deliberate client process … we don’t have a banned list, but we have a conversation that works out whether we’re appropriate for them and they’re appropriate for us. And we have … not taken on particular pieces of work where clients have wanted us to, to work for them, where they’re not—their ultimate corporate purpose is not consistent with the change we want to see in the world, or the change we want to be for ourselves.

It was after that experience that I … I felt more, um, (pause) responsible, I guess would be the best way to put it … it took on a different significance and meaning for me … to the point where I ended up leaving that organization because I felt like the impact in that space was never going to be enough for what needs to be done, and it needs to come back to each individual person and understanding their relationship with themselves and having that be right. Because when that is right, your relationship with everything else is in is in balance. And you don’t have to keep telling people not to waste things or not to like, put toxic things into their bodies because you just feel it.

[I] thought I was … [involved in social change]. But it was very much coming from this logical, wounded healer space in me where I’d grown up kind of being a rescuer, um, for my—for my mother. Um, so I was, I was very much focused on, on the doing, um, aspect of it, rather than the kind of the being and it living through me. So it wasn’t coming from this authentic place, it was coming from this wounded place in me. Um, and what I’m doing [now] actually is not too dissimilar, but it’s just coming from a completely different place in me now. Like, it’s somatic.

Me waking up has had other people have experiences and things, and I think that spreads as well. So I think that is social change and it is important. But—I haven’t reduced it to anything very specific like I’m going to protest Israel and Gaza situation. It’s not like that.

3.2.2. Theme 2: Intraconnection

Transformative experiences are helping us to move towards a greater awareness—the awareness that everything is one, everything is connected. And in my mind that is also a driving force for a form of activism. Because actually, to be active, because we are actually all one, you’re only really helping yourself—if you see what I mean.

So the face I was, it was … 100% connection with … my soul and whatever goes on behind the body. And I … came to the conclusion that everything is connected and we’re all connected, and it’s all just like this one. After that … I really started to become more aware of … how you relate to people and everything or your environment or like to take care.

I’ve been asking myself, what am I made of? My skin is dust, yeah? It goes back to that. To have realized all of everything is one—I came from that. I’ll go back there. So I belong there, I belong to nature. Everything around me looks like part of me now.

When that shift happened… it almost felt like there was a guidebook built-in or something, some kind of intuition—a lot of that was an overwhelming feeling of “I need to serve others.” It was just not about me.

I think where I found my [life] purpose is in the fact how I wanted to parent and I’ve been walking that road … from the time she was born, I have been actively changing myself so that I could be a different parent … moment to moment, day to day, month to month, year to year. All the time—learning–growing–learning–growing–learning–implementing. And then integrating, yeah, changing beliefs, but really integrating new beliefs. Letting go of old beliefs and then really, um … really then walking the walk and not just, you know, have it as a nice theory—but really put it, putting it in practice.

The beginning of last year … the internal change in me just made me happy. It told me, “no, you don’t have to hold grudges with anyone”—yeah? I went greeting all of them around Christmas time.

We started sharing a little bit about the grudges we were holding … we said ‘there is no need to hold grudges around anyone’—yeah? Because what I think about you is, is what expands in—what I think is telling what expands. So it’s all in the in the—we are all energy … because I learned that we are all energy. So if I have negative energy I’m going to meet negative energy. So after discussing, since then we are very good friends.

In addition to everything being about doing, thinking, feeling, being—we think that can be done at personal, relational, systemic and societal or global levels. And so sometimes we might be doing something that we think is going to be relational or systemic about the way they work together, but actually the transformation people start experiencing is something very personal, and it can work the opposite way around. I used to believe, but I don’t anymore believe that you have to have the inner personal transformation first before the relational and before the systemic. We think actually, sometimes we can be doing something systemic, and while we’re doing it, people start having personal experiences—the other way around.

3.2.3. Theme3: Personal Equilibrium

It became difficult to then work in the field of sustainability, because people’s understanding is—especially now with carbon—is very challenging for me because it’s so reductionist. It’s even more reductionist than waste. And it’s so far removed from what is actually happening. And it allows for people to pretend that they’re doing something when they’re not. Yeah. So I still do some work, some sustainability consulting, but I try to do as little as possible. Every time I do have to go into that space, I’m always like, “Oh, you know, this isn’t meaningful, right?”

You get into moral dilemmas. And at some point, I couldn’t sort of unite that role with who I was, with my values. So I got into a conflict in the organization. And I had to stand for my principles—and then, yeah, then it ends. And I did that one more time in another organization … So then I decided to stop putting myself in a situation where I would get into that jam every time again. So I became a sort of almost by necessity, an independent.

It just makes everything easier… except paying the bills. So we have traded that moral hypocrisy and a lot of good easy money for a moral purity, and satisfying ourselves with a level of income that we think is still sustainable.

I’ve been doing this for six years now … And it’s always been my investigation, my concept—and of course you’ve got this sort of activist energy in a sense, like, “Hey, let’s do something”. There’s a positive sort of feel to it, and yes, I’ve always had this sort of positive energy in that sense. Recently, it’s a bit tiring, I guess I’d say—in a sense the ‘no change’ of it. Everyone’s saying “We’re f*cked with the climate crisis. You know, there’s nothing we can [do], we’re all [going to die] …” It hasn’t gotten to me in the past—I was more like, “Of course we can and this and make it …”, you know? And then recently … there was just a lot more information—it just, yeah, it just felt like really hard. Of course it’s going to be something I’m going to continue to preach, but it just sometimes feels you’re nadando en la contracorriente—you’re swimming in the wrong direction—you know what I mean?

The hardest part of … living conscious more consciously—is being aware of my actions and the impact that it’s having on the earth. Um, but also kind of needing to be balanced with that, because I live in a human body, in society as it is at the moment. And we have to make money … so it’s also being more compassionate around how much I can do.

And it’s like, I’m not here to save the world, it’s fine. I’m here to do my tiny, minuscule part. And I think that that actually has been some—a kind of a huge relief for me … Recognizing, actually, no, it’s fine—I’m just, I just have to save myself. And the more I save myself, I am that kind of particle of the universe. So, it’s like, as long as I can do my best to … be that vehicle in as authentic, clean way as I can. That’s kind of my main mission, really.

4. Discussion

4.1. Intraconnection

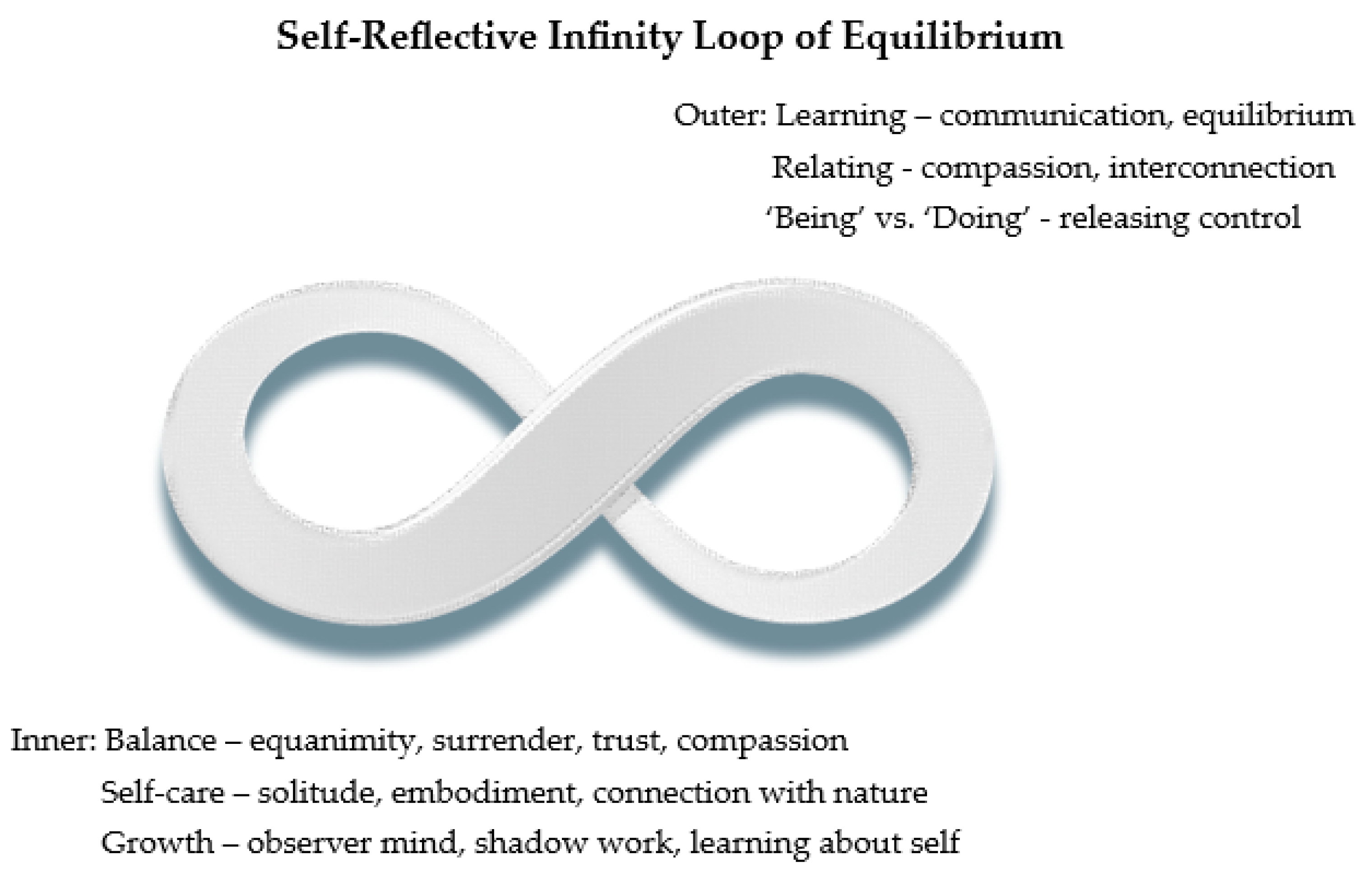

4.2. Personal Equilibrium

4.3. Social Change

“self-similar patterns that repeat themselves across a range of structures at different scales, extending from small social interactions to large national and international institutions. They can be generated by principles, values, ideas, initiatives, or endeavors that are designed with the same characteristics desired for the whole”[13]

4.4. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Lawrence, M.; Janzwood, S.; Homer-Dixon, T. What Is a Global Polycrisis? [Version 2.0. Discussion Paper 2022-4]. Cascade Institute. Available online: https://cascadeinstitute.org/technical-paper/what-is-a-global-polycrisis/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Zelenski, J.; Warber, S.; Robinson, J.; Logan, A.; Prescott, S. Nature Connection: Providing a Pathway from Personal to Planetary Health. Challenges 2023, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macy, J.; Johnstone, C. Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We’re in Without Going Crazy; New World Library: Novato, CA, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-57731-972-6. [Google Scholar]

- Shiva, V.; Shiva, K. Oneness vs the 1%: Shattering Illusions, Seeding Freedom; New Internationalist: Oxford, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-78026-513-1. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W. The Limits to Growth; The Project on the Predicament of Mankind; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ISBN 0-87663-165-0. Available online: https://1a0c26.p3cdn2.secureserver.net/wp-content/userfiles/Limits-to-Growth-digital-scan-version.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- A Revolution in Thought?—Dr. Iain McGilchrist; Darwin College Lecture Series; Darwin College, Cambridge University: Cambridge, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AuQ4Hi7YdgU (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Archer, M.S. The Mess We Are in: How the Morphogenetic Approach Helps to Explain It. J. Crit. Realism 2021, 20, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateson, N. Symmathesy—A Word in Progress: Proposing a New Word That Refers to Living Systems. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the ISSS, Berlin, Germany, 2–7 August 2015; Volume 1. Available online: https://journals.isss.org/index.php/proceedings59th/article/view/2720 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Bockler, J.; Hector, F. Nurturing the Fields of Change: An Inquiry into the Living Dynamics of Holistic Change Facilitation; Alef Trust: Wirral, UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.aleftrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/ALEF_CCP_REPORT_11_compressed.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Elias, D.G. Educating Leaders for Social Transformation; Teachers College, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 1993; Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/304053501/abstract/CE17326E59E84D8EPQ/1 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- O’Brien, K.L. Climate Change and Social Transformations: Is It Time for a Quantum Leap? WIREs Clim. Change 2016, 7, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, E. Finding Our Way in the Great Work. J. Transform. Educ. 2008, 6, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M. Personal to Planetary Transformation. Kosmos J. Glob. Transform. Fall/Winter 2007, 31–35. Available online: https://www.kosmosjournal.org/article/personal-to-planetary-transformation/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Walsh, R. The World of Shamanism: New Views of an Ancient Tradition, 1st ed.; Llewellyn Publications: Woodbury, MN, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-7387-0575-0. [Google Scholar]

- Wamsler, C.; Osberg, G.; Janss, J.; Stephan, L. Revolutionising Sustainability Leadership and Education: Addressing the Human Dimension to Support Flourishing, Culture and System Transformation. Clim. Change 2023, 177, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, C. Crisis and Grounds for Optimism. Available online: https://noetic.org/blog/crisis-and-grounds-for-optimism/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Edgar Mitchell: An Astronaut’s Epiphany on Sustainability & Consciousness; Global Academy Media: London, UK, 2015; Available online: https://vimeo.com/146463240 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Braud, W. Integral Inquiry: The Principles and Practices of an Inclusive and Integrated Research Approach. In Transforming Self and Others Through Research: Transpersonal Research Methods and Skills for the Human Sciences and Humanities; Anderson, R., Braud, W., Eds.; Suny series in transpersonal and humanistic psychology; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 71–130. ISBN 978-1-4384-3672-2. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future; World Commission on Environment and Development, Ed.; Oxford paperbacks; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-0-19-282080-8. [Google Scholar]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual Origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Bristow, J.; Cooper, K.; Steidle, G.; Taggart, S.; Sovold, L.; Bockler, J.; Oliver, T.H.; Legrand, T. Theoretical Foundations Report: Research and Evidence for the Potential of Consciousness Approaches and Practices to Unlock Sustainability and Systems Transformation. Report Written for the UNDP Conscious Food Systems Alliance (CoFSA), United Nations Development Programme UNDP; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–37. Available online: https://www.contemplative-sustainable-futures.com/_files/ugd/4cc31e_143f3bc24f2c43ad94316cd50fbb8e4a.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Ecker, U.K.H.; Lewandowsky, S.; Cook, J.; Schmid, P.; Fazio, L.K.; Brashier, N.; Kendeou, P.; Vraga, E.K.; Amazeen, M.A. The Psychological Drivers of Misinformation Belief and Its Resistance to Correction. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2022, 1, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.; O’Brien, K. Climate and Society: Transforming the Future; Polity Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; Medford, MA, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-0-7456-8442-0. [Google Scholar]

- Toomey, A.H. Why Facts Don’t Change Minds: Insights from Cognitive Science for the Improved Communication of Conservation Research. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 278, 109886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, P.M. Social Change, Cultural Evolution, and Human Development. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 8, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, M.S. Being Human: The Problem of Agency; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-0-511-15366-2. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D. Dancing with Systems; The Academy for Systems Change: Burlington, VT, USA, 2012; Available online: https://donellameadows.org/archives/dancing-with-systems/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Pomeroy, E.; Herrmann, L. Social Fields: Knowing the Water We Swim in. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2024, 60, 677–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmelmeier, M.; Hartje, J.A. Individualism and Prosocial Action: Cultural Variations in Community Volunteering. In Advances in Psychology Research; Columbus, A.M., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2007; Volume 51, pp. 149–161. [Google Scholar]

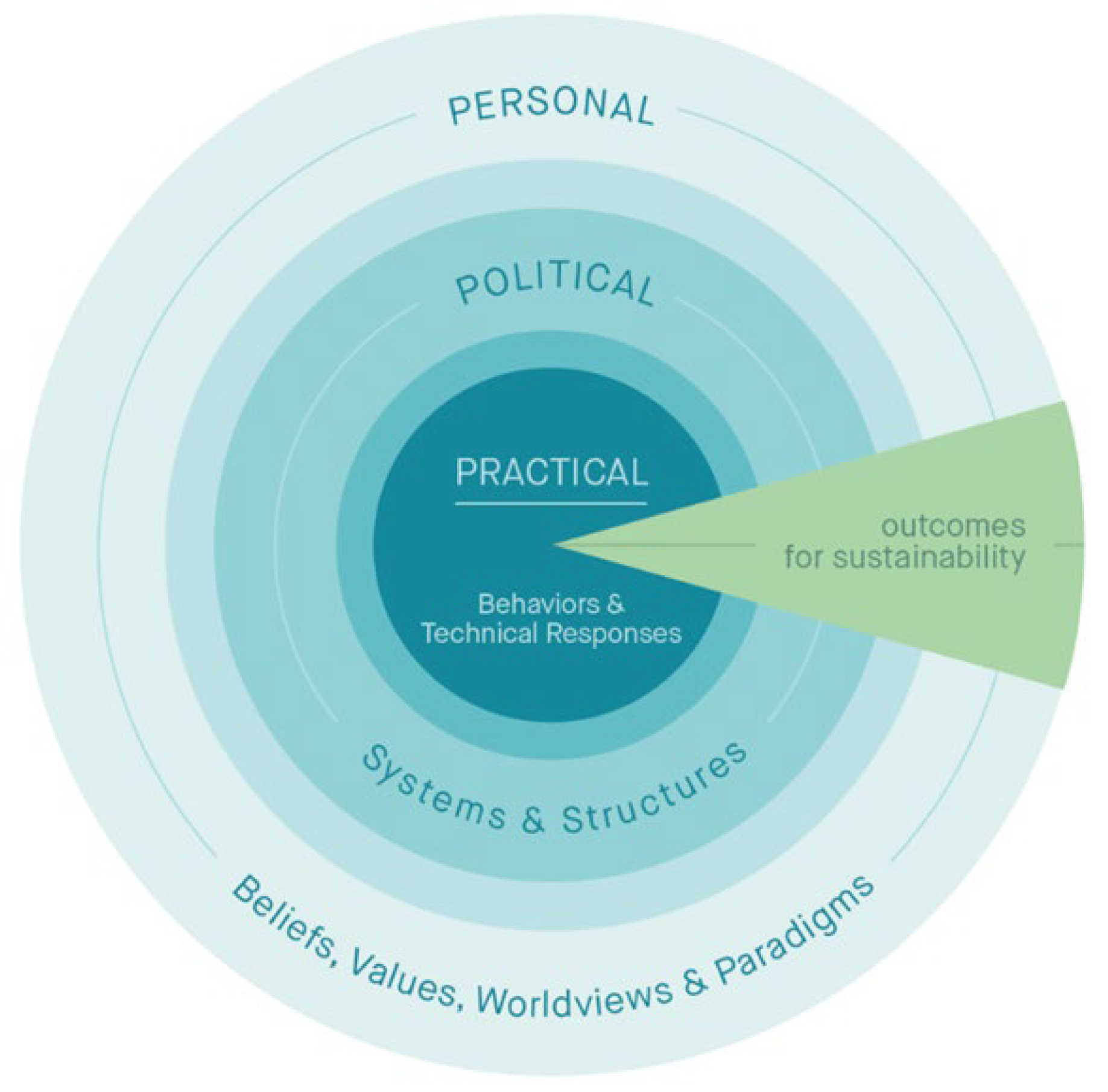

- O’Brien, K.; Sygna, L. Responding to Climate Change: The Three Spheres of Transformation. In Proceedings of the Conference Transformation in a Changing Climate, Oslo, Norway, 19–21 June 2013; University of Oslo: Oslo, Norway, 2013; pp. 16–23, ISBN 978-82-570-2000-2. [Google Scholar]

- Vieten, C.; Wahbeh, H.; Dakin, C. Models of Transformation; Produced for the Fetzer Institute; Institute of Noetic Sciences: Novato, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.V. The Exceptional Human Experience Process: A Preliminary Model with Exploratory Map. Int. J. Parapsychol. 2000, 11, 69–111. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Perspective Transformation. Adult Educ. 1978, 28, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, A.J. The Nature of Spiritual Transformation: A Review of the Literature. 2000. Available online: https://metanexus.net/archive/spiritualtransformationresearch/research/pdf/STSRP-LiteratureReview2-7.PDF (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Schlitz, M.; Vieten, C.; Amorok, T. Living Deeply: The Art & Science of Transformation in Everyday Life; New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-57224-533-4. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, D.J. IntraConnected: MWe (Me + We) as the Integration of Self, Identity, and Belonging; Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology Ser; W. W. Norton & Company, Incorporated: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-0-393-71169-1. [Google Scholar]

- Glassman, M.; Erdem, G.; Bartholomew, M. Action Research and Its History as an Adult Education Movement for Social Change. Adult Educ. Q. 2013, 63, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maton, K.I. Empowering Community Settings: Agents of Individual Development, Community Betterment, and Positive Social Change. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, J. Changes of Mind: A Holonomic Theory of the Evolution of Consciousness; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-7914-2849-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Learning: Theory to Practice. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 1997, 1997, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambrell, J. Beyond Personal Transformation: Engaging Students as Agents for Social Change. J. Multicult. Aff. 2016, 1, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Dirkx, J.M.; Mezirow, J.; Cranton, P. Musings and Reflections on the Meaning, Context, and Process of Transformative Learning: A Dialogue between John M. Dirkx and Jack Mezirow. J. Transform. Educ. 2006, 4, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, C.D.; Buys, C.; Ogunbode, C.; Palmer, M.; Rose, A.; Valerio, R. Activating Faith: Pro-Environmental Responses to a Christian Text on Sustainability. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 877–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnier, R.T.; Kernes, J.L.; Dautheribes, T.M. A Short List of Universal Moral Values. Couns. Values 2000, 45, 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nicol, D. Subtle Activism: The Inner Dimension of Social and Planetary Transformation; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4384-5751-2. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dea, J. The Conscious Activist: Where Activism Meets Mysticism; Watkins: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-78028-843-7. [Google Scholar]

- Tolle, E. A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose, 10th ed.; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-452-28996-3. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, R. Karma Yoga and Awakening Service: Modern Approaches to an Ancient Practice. J. Transpers. Res. 2013, 5, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Greyson, B. Persistence of Attitude Changes After Near-Death Experiences: Do They Fade Over Time? J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2022, 210, 692–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grof, S. Revision and Re-Enchantment of Psychology: Legacy of Half a Century of Consciousness Research. J. Transpers. Psychol. 2012, 44, 137–163. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, J.M. After-math: Counting the Aftereffects of Potentially Spiritually Transformative Experiences. J. Near-Death Stud. 2012, 31, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.A. The Amplification and Integration of Near-Death and Other Exceptional Human Experiences by the Larger Cultural Context: An Autobiographical Case. J. Near-Death Stud. 1998, 16, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardeña, E.; Lynn, S.J.; Krippner, S. The Psychology of Anomalous Experiences: A Rediscovery. Psychol. Conscious. Theory Res. Pract. 2017, 4, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greyson, B. Western Scientific Approaches to Near-Death Experiences. Humanities 2015, 4, 775–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stout, Y.M. Six Major Challenges Faced by Near-Death Experiencers. J. Near-Death Stud. 2006, 25, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- C’de Baca, J.; Wilbourne, P. Quantum Change: Ten Years Later. J. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 60, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R. Exceptional Human Experience and the More We Are: Exceptional Human Experience and Identity. Except. Hum. Exp. 1994, 15, 1–13. Available online: https://www.ehe.org/display/ehe-pagea229.html?ID=70 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Woollacott, M.; Shumway-Cook, A. Spiritual Awakening and Transformation in Scientists and Academics. Explore 2023, 19, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, J. After Awakening, the Laundry: Is Nonduality a Spiritual Experience? Int. J. Transpers. Stud. 2018, 37, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Woollacott, M.H. Conceptual Cognition and Awakening: Insights from Non-Dual Śaivism and Neuroscience. J. Transpers. Psychol. 2021, 53, 119–139. [Google Scholar]

- Schroll, M.A. Wrestling with Arne Naess: A Chronicle of Ecopsychology’s Origins. Trumpeter 2007, 23, 28–57. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.V. Ecopsychology, Transpersonal Psychology, and Nonduality. IJTS 2011, 30, 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Swan, J.A. Transpersonal Psychology and the Ecological Conscience. J. Transpers. Psychol. 2010, 42, 2–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wamsler, C.; Osberg, G.; Osika, W.; Herndersson, H.; Mundaca, L. Linking Internal and External Transformation for Sustainability and Climate Action: Towards a New Research and Policy Agenda. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 71, 102373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorard, S. Research Design, as Independent of Methods. In SAGE Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research; Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 237–252. ISBN 978-1-4129-7266-6. [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C.; Sines, M.C. Utilizing Mixed Methods in Psychological Research. In Handbook of Psychology, Volume 2: Research Methods in Psychology; Weiner, I.B., Ed.; Handbook of Psychology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 428–450. ISBN 978-0-470-61904-9. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4129-7517-9. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, J. What Can the ‘Transpersonal’ Contribute to Transformative Research? Int. J. Transform. Res. 2014, 1, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.; Braud, W. Transforming Self and Others Through Research: Transpersonal Research Methods and Skills for the Human Sciences and Humanities; Suny series in transpersonal and humanistic psychology; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4384-3672-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, D.M. Transformative Research: Personal and Societal. Int. J. Transform. Res. 2017, 4, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, D.A.; Friedman, H.L. Quantitative Assessment of Transpersonal and Spiritual Constructs. In The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Transpersonal Psychology; Friedman, H.L., Hartelius, G., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 281–299. ISBN 978-1-119-96755-2. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approache, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4129-6556-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cann, A.; Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Taku, K.; Vishnevsky, T.; Triplett, K.N.; Danhauer, S.C. A Short Form of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berwick, D.M.; Murphy, J.M.; Goldman, P.A.; Ware, J.E.; Barsky, A.J.; Weinstein, M.C. Performance of a Five-Item Mental Health Screening Test. Med. Care 1991, 29, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, M.G. Struggles Reported Integrating Intense Spiritual Experiences: Results from a Survey Using the Integration of Spiritually Transformative Experiences Inventory. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2021, 13, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.J.; Dunstan, F.D.; Lloyd, K.; Fone, D.L. Evaluating Cutpoints for the MHI-5 and MCS Using the GHQ-12: A Comparison of Five Different Methods. BMC Psychiatry 2008, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumpf, H.-J.; Meyer, C.; Hapke, U.; John, U. Screening for Mental Health: Validity of the MHI-5 Using DSM-IV Axis I Psychiatric Disorders as Gold Standard. Psychiatry Res. 2001, 105, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, J.; Carpenter, D.; Fisher, M.; Goodson, S.; Hannah, B.; Kwiatkowski, R.; Prutton, K.; Reeves, D.; Wainwright, T. BPS Code of Human Research Ethics; British Psychological Society: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-85433-792-4. Available online: https://explore.bps.org.uk/lookup/doi/10.53841/bpsrep.2021.inf180 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-5063-3020-4. [Google Scholar]

- Andoh-Arthur, J. Gatekeepers in Qualitative Research. In Research Design for Qualitative Research; Atkinson, P., Delamont, S., Cernat, A., Sakshaug, J.W., Williams, R.A., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-5264-2103-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jayawickreme, E.; Infurna, F.J.; Alajak, K.; Blackie, L.E.R.; Chopik, W.J.; Chung, J.M.; Dorfman, A.; Fleeson, W.; Forgeard, M.J.C.; Frazier, P.; et al. Post-Traumatic Growth as Positive Personality Change: Challenges, Opportunities, and Recommendations. J. Personal. 2021, 89, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamovi, version 2.3; The Jamovi Project: Sydney, Australia, 2022; Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Navarro, D.; Foxcroft, D. Learning Statistics with Jamovi: A Tutorial for Beginners in Statistical Analysis, 1st ed.; Open Book Publishers: Cambridge, UK, 2025; ISBN 978-1-80064-937-8. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Introducing qualitative methods; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-85702-913-3. [Google Scholar]

- Geldenhuys, H. Applied Ethics in Transpersonal and Humanistic Research. Humanist. Psychol. 2019, 47, 112–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, M.; Gillam, L. Ethics, Reflexivity, and “Ethically Important Moments” in Research. Qual. Inq. 2004, 10, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, M.M.; Ambagtsheer, R.C.; Casey, M.G.; Lawless, M. Using Zoom Videoconferencing for Qualitative Data Collection: Perceptions and Experiences of Researchers and Participants. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 160940691987459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, M.; Mills, J. Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide, 3rd ed.; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-5297-5928-0. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, A.E.; Charmaz, K. Grounded Theory and Situational Analysis. In SAGE Research Methods Foundations; Atkinson, P., Delamont, S., Cernat, A., Sakshaug, J.W., Williams, R.A., Eds.; Qualitative Analysis; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-5297-4740-9. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Teaching Theory Construction with Initial Grounded Theory Tools: A Reflection on Lessons and Learning. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 1610–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. But Is It Rigorous? Trustworthiness and Authenticity in Naturalistic Evaluation. New Dir. Program Eval. 1986, 1986, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankrah, D.; Bristow, J.; Hires, D.; Artem Henriksson, J. Inner Development Goals: From Inner Growth to Outer Change. Field Actions Sci. Rep. J. Field Actions 2023, 25, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Grof, S.; Grof, C. Spiritual Emergency: When Personal Transformation Becomes a Crisis, 1st ed.; Tarcher G.P. Putnam’s Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-0-87477-538-8. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, K.; Carmona, R.; Gram-Hanssen, I.; Hochachka, G.; Sygna, L.; Rosenberg, M. Fractal Approaches to Scaling Transformations to Sustainability. Ambio 2023, 52, 1448–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wamsler, C.; Schäpke, N.; Fraude, C.; Stasiak, D.; Bruhn, T.; Lawrence, M.; Schroeder, H.; Mundaca, L. Enabling New Mindsets and Transformative Skills for Negotiating and Activating Climate Action: Lessons from UNFCCC Conferences of the Parties. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 112, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, M.G. Recovering Balance After the Big Leap: Overcoming Challenges in Integrating Spiritually Transformative Experiences (STEs) (Publication No. 10600749). Ph.D. Thesis, Sofia University, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley, M. Troubles with Triangulation. In Advances in Mixed Methods Research; Bergman, M.M., Ed.; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 22–36. ISBN 978-1-4129-4809-8. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, P.M. Linking Social Change and Developmental Change: Shifting Pathways of Human Development. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 45, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.P.; Cesário, F.; Sabino, A.; Moreira, A. Pro-Environmental Messages in Job Advertisements and the Intentions to Apply—The Mediating Role of Organizational Attractiveness. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon de la Barca, L.; Milligan, K.; Kania, J. Healing Systems. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2024. Available online: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/healing-trauma-systems (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Hübl, T.; Shridhare, L. ‘Tender Narrator’ Who Sees Beyond Time: A Framework for Trauma Integration and Healing. JASC 2022, 2, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Strasser, J.; Schäpke, N. Overcoming Polarization in Crises: A Research Project on Trauma and Democracy with over 350 Citizens; Pocket Project e.V.: Wardenburg, Germany; Mehr Demokratie e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2022; 87p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 101 | 69.7 |

| Male | 42 | 28.9 |

| Transgender | 1 | 0.7 |

| Gender Fluid | 1 | 0.7 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian/White | 120 | 82.7 |

| Other | 25 | 17.3 |

| Country/Region | ||

| United States | 55 | 37.8 |

| United Kingdom | 41 | 28.3 |

| Canada | 16 | 11.0 |

| Europe | 15 | 10.3 |

| Australia/New Zealand | 6 | 4.2 |

| Africa | 4 | 2.8 |

| South Asia | 4 | 2.8 |

| Other | 4 | 2.8 |

| Education | ||

| Bachelors | 44 | 30.3 |

| Masters | 32 | 22.0 |

| Some college, no degree | 23 | 15.9 |

| MD/PhD/JD | 22 | 15.2 |

| Trade school/Associates | 12 | 8.3 |

| H.S. diploma or equivalent | 11 | 7.6 |

| No H.S. diploma | 1 | 0.7 |

| Current Age * | Age at Time of Experience * | Time Since Experience * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 55 | 38 | 12 |

| Standard deviation | 13.9 | 14.6 | 15.9 |

| Minimum | 26 | 3 | 0.25 |

| Maximum | 93 | 76 | 65 |

| Shapiro-Wilk p | 0.347 | 0.707 | <0.001 |

| Current Age * | Age at Time of Experience * | Time Since Experience * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 45.5 | 37.0 | 6.25 |

| Standard deviation | 12.2 | 13.4 | 12.0 |

| Minimum | 22 | 5 | 1 |

| Maximum | 72 | 70 | 54 |

| Shapiro-Wilk p | 0.229 | 0.727 | <0.001 |

| Median Current Age * | Median Age at Time of Experience * | Median Time Since Experience * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screened in a | 55 | 38 | 12 |

| Low MHI-5 b | 45.5 | 37.0 | 6.25 |

| Delta | 9.5 ** | 1.0 | 5.75 ** |

| Category | Personal Practices and Supportive Conditions |

|---|---|

| Contemplative practices | Meditation, mindfulness, prayer, mantra, chanting, practicing observer mind |

| Self-discovery | Becoming an expert on myself, journaling, counseling, taking courses, reading, plant medicine |

| Self-care | Self-love, self-compassion, exercise, yoga, good food, quality sleep |

| Embodying values | Integrity, gratitude, compassion, discernment, authenticity |

| Time in nature | Being outside, gardening, wild swimming, walking, hiking |

| Personal environment | Solitude, calm, quiet, decreased sensory input, fresh air, clean, uncluttered |

| Connection | With peer-groups, like-minded people, intimate partner, supportive friend(s), community, family |

| Creative expression | Making art, making music, dancing, writing, creating poetry, cooking |

| Expanding awareness | Of subtle world, of intraconnection, of self, of causes of suffering |

| Category | Limiting Factors |

|---|---|

| Personal challenges | Getting started, need to do own work first, fear of judgement, fear of rejection, fear of failure, need for balance of work and personal life, need to maintain personal equilibrium, personal insecurity |

| Demands of Daily Life | Lack of time, family commitments, limits on energy, challenges of daily life, parenting commitments |

| Cultural Characteristics | Prevalent illusion of separation, collective resistance to change, entrenched dominant belief system, discomfort of polarized atmosphere, predominant capitalist agenda |

| Financial Concerns | Personal financial concerns, insufficient pay for social change work, lack of funding sources for project work |

| Group Dynamics | Avoidance of othering, avoidance of organizations with patriarchal structures, avoidance of commercial aspirations, avoidance of polarization, hostility, and negativity, avoidance of questionable ethics |

| Personal Limitations | Limited stamina, age limitations, health challenges, limited personal capacity, personal circumstances |

| Category | Supportive Factors |

|---|---|

| Supportive Elements | Shifting social landscape, reciprocal benefits from like-minded connections, being inspired by others, core beliefs, inner resilience |

| Personal Equilibrium | Sustaining personal practices, contemplative practice, maintaining preferred personal environment, ongoing skill development, creative expression, use of therapeutic approaches |

| Personal Perspective | Positive intentions to contribute, aligning life purpose with external efforts, awareness of personal agency, the nature of reality, and interconnection; embodiment of personal values, beliefs, and understandings |

| Connection with Others | Like-minded community, spiritual community, social change community, peer support group, supportive relationship, and/or friend, family connection |

| External Actions | Being of service, ethical career, ethical consumer choices, supporting wellbeing of others, social justice activities, philanthropic donations |

| Pseudonym | Gender | Age | Ethnicity | Location | Education | Years Since Experience | Interest and Engaged? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ana | F | 29 | Caucasian | Spain | Masters | 10 | Y/Y |

| [Maya] a | [F] | [32] | [Asian] | [India] | [Masters] | [10] | [Y/Y] |

| Ibrahim | M | 42 | African | Kenya | Bachelors | 2 | Y/Y |

| Muriel | F | 42 | Caucasian | USA | Masters | 5 | Y/Y |

| Oliver | M | 43 | Caucasian | UK | Bachelors | 1 | N/N |

| Diane | F | 48 | Caucasian | UK | Masters | 12 | Y/Y |

| Neil | M | 54 | Caucasian | Europe | Adv. Degree | 7 | Y/Y |

| Emilia | F | 54 | Caucasian | Switzerland | Masters | 11 | Y/N |

| Lars | M | 58 | Caucasian | Netherlands | Masters | 28 | Y/N |

| David | M | 67 | Caucasian | UK | Bachelors | 8 | Y/Y |

| Practice | Ana | Oli | Emi | Nei | Mul | Lar | Dia | Ibr | Dav |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avoiding othering | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Meditation | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Aligning/harmonizing inner and outer worlds | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Time in nature | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Reading on spirituality | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Creativity—writing | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Self-compassion practice | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Sufficient solitude | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Physical exercise/yoga | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Observer mind practice | X | X | X |

| Category | Specific Values |

|---|---|

| Commitment to something greater than oneself |

|

| Self-respect—accompanied by humility, self-discipline, and acceptance of personal responsibility |

|

| Respect and care for others |

|

| Care for other living things and the environment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Halliday, E.; Bockler, J. How Transformative Experiences Reshape Values, Worldviews, and Engagement with Sustainability: An Integral Inquiry. Challenges 2025, 16, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16030030

Halliday E, Bockler J. How Transformative Experiences Reshape Values, Worldviews, and Engagement with Sustainability: An Integral Inquiry. Challenges. 2025; 16(3):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16030030

Chicago/Turabian StyleHalliday, Elizabeth, and Jessica Bockler. 2025. "How Transformative Experiences Reshape Values, Worldviews, and Engagement with Sustainability: An Integral Inquiry" Challenges 16, no. 3: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16030030

APA StyleHalliday, E., & Bockler, J. (2025). How Transformative Experiences Reshape Values, Worldviews, and Engagement with Sustainability: An Integral Inquiry. Challenges, 16(3), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16030030