The Gendered Space of the “Oriental Vatican”—Zi-ka-wei, the French Jesuits and the Evolution of Papal Diplomacy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

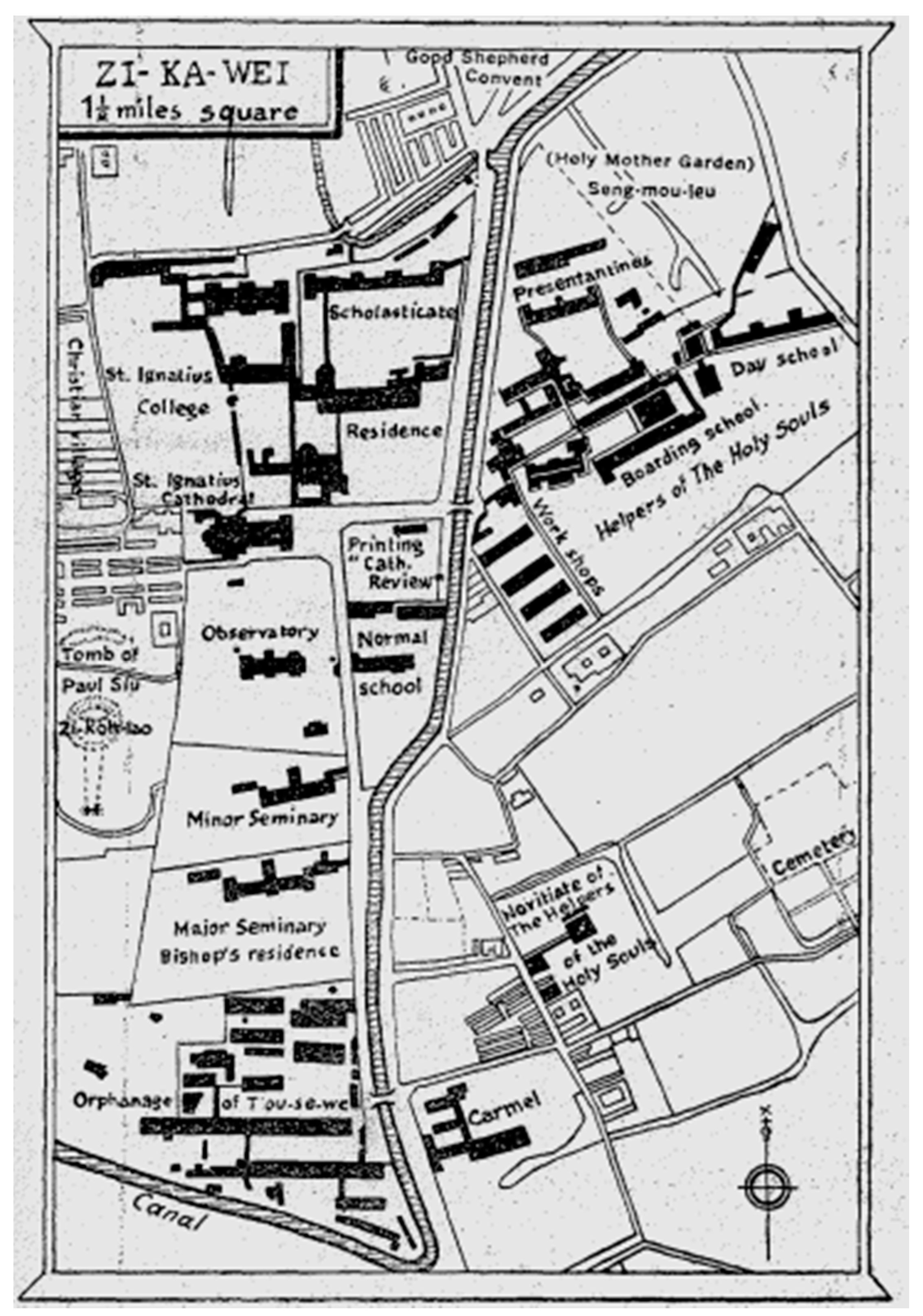

2. Site Selection and Structure of the Jesuit Compound in Shanghai

3. The Compound and Protectorate under the Sino-French Conventions

Apart from that, [there is] no right, no strict obligation in the basis of our protectorate. Nothing binds Catholic missionaries to our operation. If all, from whatever countries they hail, have gave up to now resorted to French protection, it is because this protection was the best to be offered them, without distinction of nationalities, strongly enough organized to be efficacious with the Chinese authorities and constituting an assemblage of advantages substantial enough to connect the missionaries to it. Thus our protectorate became a tradition, and the beneficiaries have never had reason to complain about it.12

4. Female Orders in Zi-ka-wei as an Echo of Catholic Evangelistic Energy

The Virgins, because of their instruction, are especially in ascendancy. These fine girls, who have renounced marriage to serve the cause of religion and have spent years studying, render us immense services. Chinese women, who never engage in studies, look on them as oracles. In the Catholic communities where they [the Virgins] sojourn, they train girls, preach, catechize, lead prayers, prepare the ille [sic] for death, keep the church clean, etc. They are generally from the thirties to forty years old. They always have with them one or two orphans, who follow them. We give to one Virgin the equivalent of eight fr. per month. With that they have to feed themselves.19

5. The Pope’s Absence in Global Instabilities, and the Fall of Ecclesiastical France

6. A Solutions from China? The Refraction of Europe in Zi-ka-wei

Yet, notwithstanding the Roman Pontiff`s insistence, it is sad to think that there are still countries where the Catholic faith has been preached for several centuries, but where you will find no indigenous clergy, except for an inferior kind… nations which for many centuries have come under the salutary influence of the Gospel and the Church, and have yet been able to yield neither bishops to rule them, nor priests to direct them. Therefore, to all appearances, the methods used in various places to train a clergy for the missions have up to now been defective and distorted.35

Suppose the missionaries then to be in any way preoccupied with worldly interests, and, instead of acting in everything like an apostolic man, to appear to further the interests of his own country, people will at once suspect his intentions, and may be led to believe that the Christian religion is the exclusive property of some foreign nation; that adhesion to this religion implies submission to a foreign country and the loss of one`s own national dignity.

7. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benedict XV. 1919. Maximum Illud: Apostolic Letter on the Propagation of the Faith throughout the World. Translated by Thomas J. M., and Burke S.J.. Available online: https://www.svdcuria.org/public/mission/docs/encycl/mi-en.htm (accessed on 15 January 2011).

- Brockey, Liam Matthew. 2007. Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1570–1724. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Brook, Timothy, and Gregory Blue. 1999. China and Historical Capitalism: Genealogies of Sinological Knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge Univerisity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cannone, Domenico. 1987. Lèvangelizzazione della provincia cinese del Ho-non nella seconda metà del secolo XIX. Naples: Pontificio Instituto Missioni Estere. [Google Scholar]

- China. Hai guan zong shui wu si shu. 1917. Treaties, Conventions, etc., between China and Foreign States; Shanghai: Statistical Department of the Inspectorate General of Customs.

- Cummins, J. S. 2016. Christianity and Missions, 1450–1800. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- d’Elia, Pasquale M. 1927. Catholic Native Episcopacy in China: Being an Outline of the Formation and Growth of the Chinese Catholic Clergy, 1300–1926. Shanghai: Tòu-Sè-Wè Press, p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne, George H. 1962. Generation of Giants: The Story of the Jesuits in China in the Last Decades of the Ming Dynasty. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gernet, Jacques. 1985. China and the Christian Impact. Translated by Janet Lloyd. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Michael. 1991. The Franco-Prussian War: The German Invasion of France 1870–1871. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- La Servière, Joseph de. 1925. La nouvelle mission de Kiang-nan (1840–1922). [The new Jiang-nan mission (1840–1922)]. Shanghai: Impromerie de la Mission, Orphelinat de T`ou-sè-wè, Zi-ka-wei. [Google Scholar]

- Lacouture, Jean. 1991. Jésuites: Une multibiographie: Les Conquérants. Paris: Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Menegon, Eugenio. 2009. Ancestors, Virgins, and Friars: Christianity as a Local Religion in Late Imperial China. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Molony, John, and David Thompson. 2006. 10: Christian Social Thought; A: Catholic Social Teaching. In World Christianities c. 1815–c.1914. Cambridge History of Christianity. Vol.8. Edited by Sheridan Gilley and Brian Stanley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pfister, Louis. 1932. Notices biographiques ET bibilographiques sur les Jésuites de l`ancienne mission de Chine, 1552–1773. Shanghai: Imprimerie de la Mission Catholique, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Schapiro, J. Salwyn. 1921. Modern and Contemporary European History (1815–1921). Cambridge: The Riverside Press. [Google Scholar]

- Soetens, Claude. 1997. LÈglise catholique en Chine au XXe siècle. Paris: Editions Beauchesne, pp. 104–5. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Haojie, ed. 2005. Zikawei History [历史上的徐家汇]. Shanghai: Shanghai Culture Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Tiedemann, R. G. 2010. Handbook of Christianity in China. Leiden: Brill Publisher, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Waley-Cohen, Joanna. 2006. Culture of War in China: Empire and the Military under the Qing Dynasty. New York: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Worcester, Thomas, ed. 2017. The Cambirdge Encyclopedia of the Jesuits. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Albert. 2018. In the shadow of empire: Josef Schmidlin and Protestant–Catholic Ecumenism before the Second World War. Journal of Global History 13: 165–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Yihua, ed. 1997. Record of Xuhui District. Shanghai: Shanghai Academy of Social Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Ernest P. 2013. Ecclesiastical Colony: China’s Catholic Church and the French Religious Protectorate. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The Jesuits had been suppressed globally by the papal brief Dominus ac Redemptor (21 July, 1773). After seven decades, the order was restored. To designate the two generations before and after the restoration, the term “New Jesuit” was invented, but it most often refers to those who worked after the restoration in particular. See the entry term “China” (Worcester 2017, p. 164). |

| 2 | As a territorial division of the Catholic Church in apostolic vicariates or perfectures in the 19th century, Jesuits ultimately served in nine different areas, led by Shanghai staffed by French Jesuits of the Paris province. See (Gernet 1985, p. 17). |

| 3 | It took some time after the restoration of the Society of Jesus in 1814 before New Jesuits were sent to China. After multiple requests by Chinese Christians, the first three French Jesuits led by Claude Gotteland (南格祿, 1803–1856) finally arrived in China in 1842. They arrived in Hengtang at first and built their residence and 5 years later, they were able to move into the central part of Shanghai. It was in 1847 that construction on the Jesuit Residence in Zi-ka-wei was started. |

| 4 | “Generation of Giants” was a specified term for the first generation of Jesuits who worked in China from 1582 to 1775, see (Dunne 1962). |

| 5 | On the relationship between the New Jesuits and the remnant old communities of Catholics who had survived since the eighteenth century, “Given the relative paucity of European personnel, it is important to note that the number of Catholic faithful, in spite of the periodic persecutions, had increased by about 100,000 by the middle of the nineteenth century. At the same time, priestly duties were performed primarily by the Chinese clergy. As a matter of fact, Chinese Catholics had developed their own patterns of church life.” See (d’Elia 1927, p. 50). |

| 6 | Like the British and Americans, the French were supposed to be confined to the environs of these five treaty ports. However, the French treaty specified that, if a French person violated this restriction and “proceeded far into the interior”, they should be conducted unharmed to the French consul in the nearest treaty port. Although it made no mention of missionaries, they were the object of interest here. See (China. Hai guan zong shui wu si shu 1917, pp. 771–813). |

| 7 | Restrictions embodied in a formal Sino-Franco treaty and agreed to in discussion about a Chinese toleration pronouncement. See (Gernet 1985, p. 83). |

| 8 | Under the Treaty of Tianjin, special passports were issued as envisioned in Articles 8 and 13. See Tableau des Traité, Conventions et arrangements divers, relatifs au Protectorat de La Franc sur les chrétientés en Chine. 10 May 1900, file box 59. Archives Diplomatiques de Nantes, documents of the French legation in Beijing. Paris and (Cannone 1987, p. 116). |

| 9 | The Beijing Convention, another Franco-Chinese treaty, was imposed in 1860 under the threat of military continued occupation of the imperial capital, additions were made that opened the door to endless complications and conflict. Article 6 of the convention treated Christians and their religion. Part of the reason that the article led to so much controversy was that it treated property, never an easy topic. Another part of the problem was the ambiguity engendered by differing texts. The French and Chinese version of Article 6 of the Beijing Convention were conspicuously divergent in phraseology and even in content. |

| 10 | Missionaries as Italian, Belgian, German, Austrian, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, and Irish, as well as French. |

| 11 | Tòou-sè-wè was also a Romanized spelling of the pronunciation in Shanghai dialect. |

| 12 | Crise de notre Protectorat religieux en Chine (1886–1892). Archives Diplomatiques de Nantes, documents of the French legation in Beijing, file box 59, which states “The memorandum is not dated. Internal evidence suggests that it was written about 1898. Since one German-staffed vicariate had already departed from the French Protectorate, the reference to ‘all’ missionaries was not exact.” Quoted in (Young 2013, p. 42). |

| 13 | See (Xiao 1997, p. 45). |

| 14 | Goa was the beginning point of the early Jesuits as they expanded into the Indian subcontinent, and later it was the seat of the first Jesuit province to be established in Asia. Francis Xavier led the way in 1542 at the request of the Portuguese king, under whose patronage (the Padroado) the Pope had entrusted the mission. Jesuits ministered to the native population in Goa and its environs, quickly becoming a base for missions throughout India. See (Pfister 1932, pp. 95–102). |

| 15 | Many notable Jesuits spent time in Macau. This territory was established by the Portuguese in 1557 for the purpose of exploration and trade in China. Despite its small size, its prime location on a tip of a peninsula on the southern Chinese coastline facilitated rapid population growth. Most early inhabitants were Portuguese merchants and their families; they were rapidly joined by various religious orders, including the Jesuits. The Christian population more than doubled, from 400 to 1000, in the first twenty-five years of the settlement’s existence. A Jesuit residence was built in 1565 and Jesuit official visitor Alessandro Valignano (範禮安, 1539–1606) arrived in 1577. Ten months spent awaiting favorable weather for sailing to Japan allowed him time to observe, evaluate and establish the policy of cultural accommodation. Michele Ruggieri (羅明堅, 1543–1607) arrived in Macau two years later, and Matteo Ricci in 1583. They began studying the Chinese language and preparing for their historic mission work there. See (Brockey 2007). |

| 16 | Wrote the chronicler of the Jesuits’ return to Jiang-nan: “In more than one village, a Virgin had usurped the functions of administrator. Almost everywhere they led the chanting of prayers at the church, gave pious readings, and admonished delinquents.” See (La Servière 1925) The English translation was quoted from (Young 2013, p. 20). |

| 17 | Some of the unmarried Jiang-nan laywomen were encouraged to organise themselves into an indigenous religious association. Virgins of the Presentation did not take the vows, was under the authority of the French mission superior to instruct and form the girls. The French sisters took charge of girl orphans and pupils at the Notre Dame. In this context, it can be argued that Virgins was coming into contact and working with foreign sisters and becoming attracted to a life in a communal religious environment. See (Tiedemann 2010, pp. 587–99). |

| 18 | Direct Catholic evangelization among women continued to be undertaken by the “institutes of virgins”, namely unwed Chinese Catholic women who had dedicated their lives to God and the mission, as well as by the emerging diocesan-level Chinese sisterhood… See (Tiedemann 2010, pp. 319–21). |

| 19 | R.G. Tiederman indicates that the Catholic Virgins were generally supported by their families, implying a certain affluence, but that others might support themselves by labor, like textile production, or might receive mission subsidies. See (Menegon 2009, pp. 332–42). |

| 20 | With the French garrison gone, widespread public demonstrations demanded that the Italian government take Rome. But Rome remained under French protection on paper, therefore an attack would still have been regarded as an act of war against the French Empire. Furthermore, although Prussia was at war with France, it had gone to war in an uneasy alliance with the Catholic South German states that it had fought against (alongside Italy) just four years earlier. It was only after the surrender of Napoleon and his army at the Battle of Sedan the situation changed radically. The French Emperor was deposed and forced into exile. The best French units had been captured by the Germans, who quickly followed up their success at Sedan by marching on Paris. Faced with a pressing need to defend its capital with its remaining forces, the new French government was clearly not in a military position to retaliate against Italy. In any event, the new government was far less sympathetic to the Holy See and did not possess the political will to protect the Pope’s position. Finally, with the French government on a more democratic footing and the seemingly harsh German peace terms becoming public knowledge, Italian public opinion shifted sharply away from the German side in favour of France. With that development, the prospect of a conflict on the Italian peninsula provoking foreign intervention all but vanished. See (Howard 1991, p. 123). |

| 21 | The capture of Rome (Italian: Presa di Roma) on 20 September 1870 was the final event of the long process of Italian unification known as the Risorgimento, marking both the final defeat of the Papal States under Pope Pius IX and the unification of the Italian peninsula under King Victor Emmanuel II of the House of Savoy. The capture of Rome ended the approximate 1116-year reign (AD 754 to 1870) of the Papal States under the Holy See and is today widely memorialized throughout Italy with the street name in virtually every town of any size. As nationalism swept the Italian Peninsula in the 19th century, efforts to unify Italy were blocked in part by the Papal States, which ran through the middle of the peninsula and included the ancient capital of Rome. The Papal States were able to fend off efforts to conquer them largely through the pope’s influence over the leaders of stronger European powers such as France and Austria. When Rome was eventually taken, the Italian government reportedly intended to let the pope keep the part of Rome west of the Tiber called the Leonine City as a small remaining Papal State, but Pius IX refused. One week after entering Rome, the Italian troops had taken the entire city save for the Apostolic Palace; the inhabitants of the city then voted to join Italy. See (Schapiro 1921, p. 160). |

| 22 | Rerum novarum (from its opening words, with the direct translation of the Latin meaning “of the new things”), or Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor, was an encyclical issued by Pope Leo XIII on 15 May 1891. It was an open letter, passed to all Catholic Patriarchs, Primates, Archbishops and bishops, that addressed the condition of the working classes. It discussed the relationships and mutual duties between labor and capital, as well as government and its citizens. Of primary concern was the need for some amelioration of “The misery and wretchedness pressing so unjustly on the majority of the working class.” It supported the rights of labor to form unions, rejected socialism and unrestricted capitalism, whilst affirming the right to private property. See (Molony and Thompson 2006, pp. 148–49). |

| 23 | Alfred Dreyfus was a French Jewish artillery officer whose trial and conviction in 1894 on charges of treason became one of the tensest political dramas in modern French history with a wide echo in all Europe. Known today as the Dreyfus Affair, the incident eventually ended with Dreyfus’s complete exoneration. |

| 24 | See the entry “France” (Worcester 2017, p. 310). |

| 25 | The big crisis in the relations with the new Republic came already in 1880. They weren’t exactly forbidden to be Jesuits, but they also not recognized as a legal association. Perhaps most significantly, they were banned from they were teaching and their educational institutions were abolished. Many therefore went abroad to work, and those that stayed just had the status of private citizens. A particular interesting point was that in the 1878 nearly one third of all Jesuits were French, and an even larger proportion of Jesuit missionaries were French. See (Lacouture 1991, p. 250). |

| 26 | Recent scholarship has preferred the term Boxer Uprising (leaving open the question of the relationship between the movement and the government), or the Boxer War (at its climax, there was a war between the Qing court and an assemblage of eight allied countries). See (Waley-Cohen 2006; Brook and Blue 1999). |

| 27 | Pichon, 3 June 1899: “the creation of spheres of influence inevitably runs counter to [the protection of missions] … It will become less and less easy to give indications to the Chinese government of possible military interventions on our part to bring justice to our protégé.” Documents diplomatiques francaus (1871–1914), 1st series, vol. 16, p. 336. The English translation was quoted in (Young 2013, p. 79). |

| 28 | Louis Ratard (acting concul-general) to Delcassé, Shanghai, 27 July 1901: Archives du Ministère des Affairs Etrangères, n.s. 327. |

| 29 | Delcassé to French ambassador in Constantinople and the French ministers in Beijing and Cairo (n.d): Archives du Ministère des Affairs Etrangères, n.s. 312. |

| 30 | S. Jarlin to Gotti (Propaganda perfect), Beijing, 13 February 1906: Pro A, vol. 490, p. 237r. |

| 31 | Beauvais (consul in Guangzhou) to Conty (minister in Beijing), #75, Guangzhou, 20 March 1913: Archives Diplomatiques de Nantes, documents of the French legation in Beijing, file box 59. |

| 32 | See (Tiedemann 2010, pp. 571–86). |

| 33 | See (Benedict XV 1919). |

| 34 | See (Soetens 1997). |

| 35 | See (Cummins 2016, p. 97). |

| 36 | The crucial issues, namely (1) the reduction of tension between foreign and Chinese Priests; (2) the phased transfer of mission territory to the Chinese clergy; and (3) the elimination of the French Protectorate. See (Tiedemann 2010, pp. 571–86). |

| 37 | See (Wu 2018, pp. 165–87). |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mo, W. The Gendered Space of the “Oriental Vatican”—Zi-ka-wei, the French Jesuits and the Evolution of Papal Diplomacy. Religions 2018, 9, 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9090278

Mo W. The Gendered Space of the “Oriental Vatican”—Zi-ka-wei, the French Jesuits and the Evolution of Papal Diplomacy. Religions. 2018; 9(9):278. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9090278

Chicago/Turabian StyleMo, Wei. 2018. "The Gendered Space of the “Oriental Vatican”—Zi-ka-wei, the French Jesuits and the Evolution of Papal Diplomacy" Religions 9, no. 9: 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9090278

APA StyleMo, W. (2018). The Gendered Space of the “Oriental Vatican”—Zi-ka-wei, the French Jesuits and the Evolution of Papal Diplomacy. Religions, 9(9), 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9090278