Abstract

The Second Temple period is considered both a pinnacle and a low point in the history of Jerusalem. One manifestation of the sharp fluctuations in Jerusalem’s status is its flora and ecology. The current study aims to address the historical events and the Talmudic traditions concerning the flora and landscape of Jerusalem. In the city’s zenith, the Jewish sages introduced special ecological regulations pertaining to its overall urban landscape. One of them was a prohibition against growing plants within the city in order to prevent undesirable odors or litter and thus maintain the city’s respectable image. The prohibition against growing plants within the city did not apply to rose gardens, maybe because of ecological reasons, i.e., their contribution to aesthetics and to improving bad odors in a crowded city. In the city’s decline, its agricultural crops and natural vegetation were destroyed when the beleaguered inhabitants were defeated by Titus’ army. One Talmudic tradition voices hope for the rehabilitation of the flora (“shitim”) around the city of Jerusalem. Haggadic-Talmudic tradition tries to endow Jerusalem with a metaphysical uniqueness by describing fantastic plants that allegedly grew in it in the past but disappeared as a result of its destruction.

1. Introduction

Historically and nationally, the Second Temple period is considered both a pinnacle and a low point in the history of Jerusalem. At that time, the city served as a vibrant spiritual hub of the Jewish people, a temple city, and a center of attraction for pilgrims (Safrai 1965; Goodman 1999; Levine 2002). In contrast, toward the end of this period, after the destruction of the Temple in 70 AD by the Romans, its status was drastically reduced, and it became a symbol of a disintegrated social system and a ruined physical, economic, and spiritual structure. The destruction of Jerusalem concluded a lengthy period in the city’s development, expanding from a small town established in the Bronze period on the City of David extension to become a large city by the end of the Second Temple period (Levine 1984, pp. 171–93).

One manifestation of the sharp fluctuations in Jerusalem’s status is its flora. In the city’s zenith the Jewish sages introduced special ecological regulations pertaining to its overall urban landscape, and in its decline its agricultural crops and natural vegetation were destroyed when the beleaguered inhabitants were defeated by Titus’ army. The purpose of this article is to discuss factors that affected the plants that grew in the city and its environs, and I shall focus on two major topics: The first one is the religious and the environmental regulations pertaining to vegetation, instituted by the town’s religious leaders in routine times. The second is the destruction of the vegetation and agriculture in the agricultural hinterland during the siege on the city in the time of the Great Revolt (66–70 CE). When the Second Temple was in operation, the ritual activities and burning of the sacrificial offerings had a significant impact on the flora in the city’s vicinity, and I shall discuss this matter elsewhere.

Research of Ancient Landscapes—Methodological Aspects

When attempting to explore the vegetative and ecological reality in Jerusalem during the Roman period we are confronted with two types of sources: literary and archeological.

Literary material—Some sources provide realistic historical portrayals, for example Josephus’ descriptions of the devastation of the city’s flora during the siege in the time of the Great Revolt (see below). Others are Mishnaic and Talmudic sources1 that include descriptions or memories reconstructing life in this period retrospectively, several years after the events depicted. Moreover, rabbinical sources do not necessarily reflect accurate historical circumstances, rather their purpose is to glorify Jerusalem and form an ideal image of a sacred space while also giving voice to its tragic destruction, sometimes exaggeratedly so (on the considerations for utilizing rabbinical sources as realistic-historical evidence see: Safrai 2011).

At the same time, it is clear that the religious literature contains a historical kernel of truth, based on the events that occurred and affected the city and its inhabitants (on the image of Jerusalem in rabbinical literature and the nature of the sources that address this see: Gafni 1999). Rabbinical sources describing Jerusalem originate both from Eretz Israel and from Babylon. Methodologically, Eretz Israel sources clearly have historical preference over the Babylonian literature of the Amoraic period (3th–5th centuries), as the spiritual center in Babylon was distant from the Eretz Israel traditions and the geographical and historical distance probably affected the authenticity of the traditions passed on among the generations.

Archeology—Research on descriptions of ancient landscapes utilizes ancient material finds as well. “Landscape archeology” is a field of research that deals with the spatial design and planning of towns and their environs in ancient periods. Jean-Louis Huot aptly expressed the relationship between man and landscape as follows: “There is a dialogue between man and landscape, which in effect articulates human culture (Huot 1999).” Artificial landscapes designed by human beings are reflected in forms of settlement, such as large cities or villages and the landscape surrounding them, i.e., the economic, agricultural, cultural, or administrative hinterland, with an affinity between the towns and their environs (Hopkins 1980; Schwartz 1991). Destruction of landscape components and desertification are another measure of activities and relationships between nations in a certain geographic region.

Studies in landscape archeology indicate that, as a rule, the general landscape of the city and its close environs in ancient times included the following three zones:

- The inhabited urban area, sometimes bordered by a protective wall.

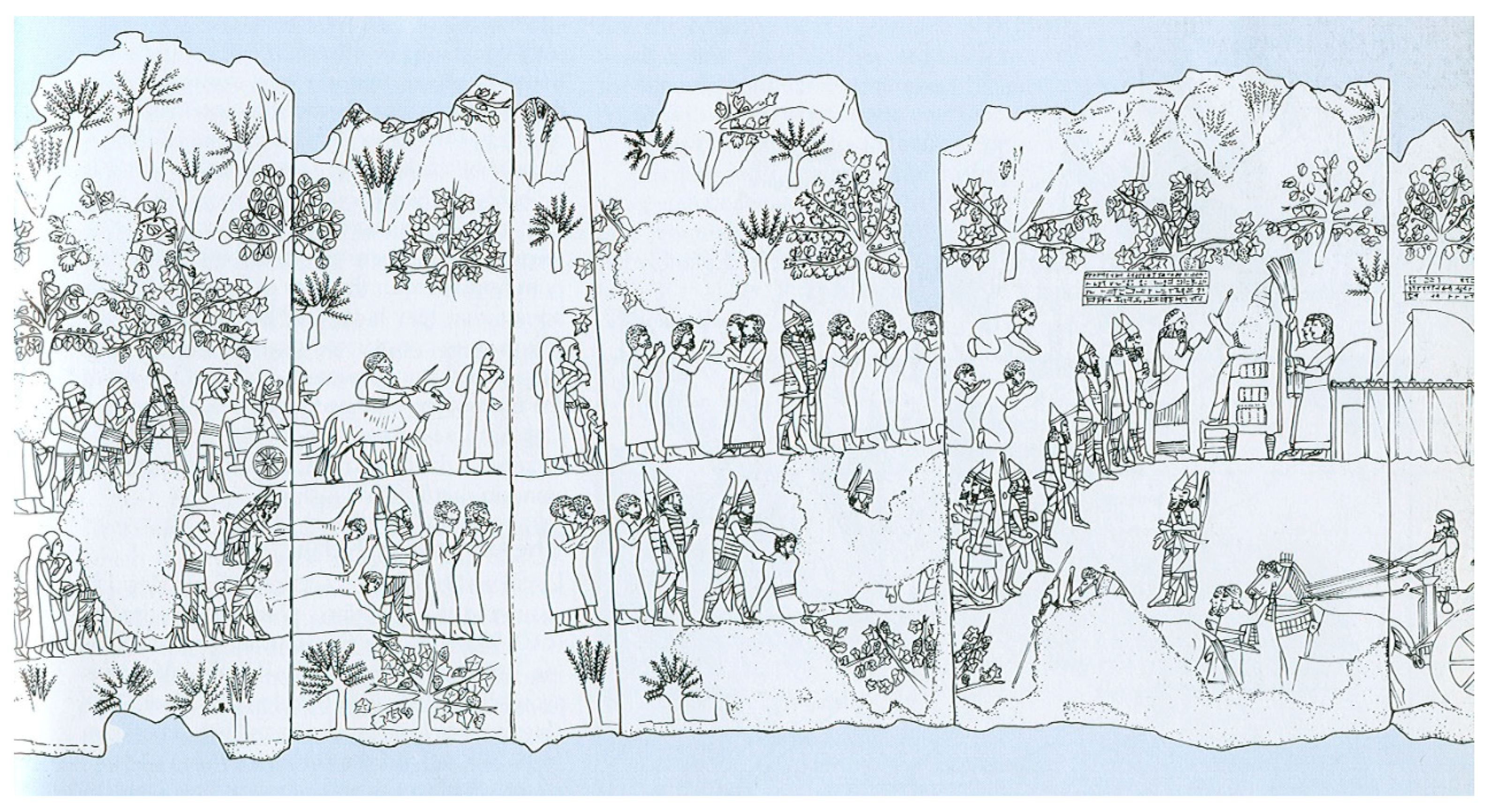

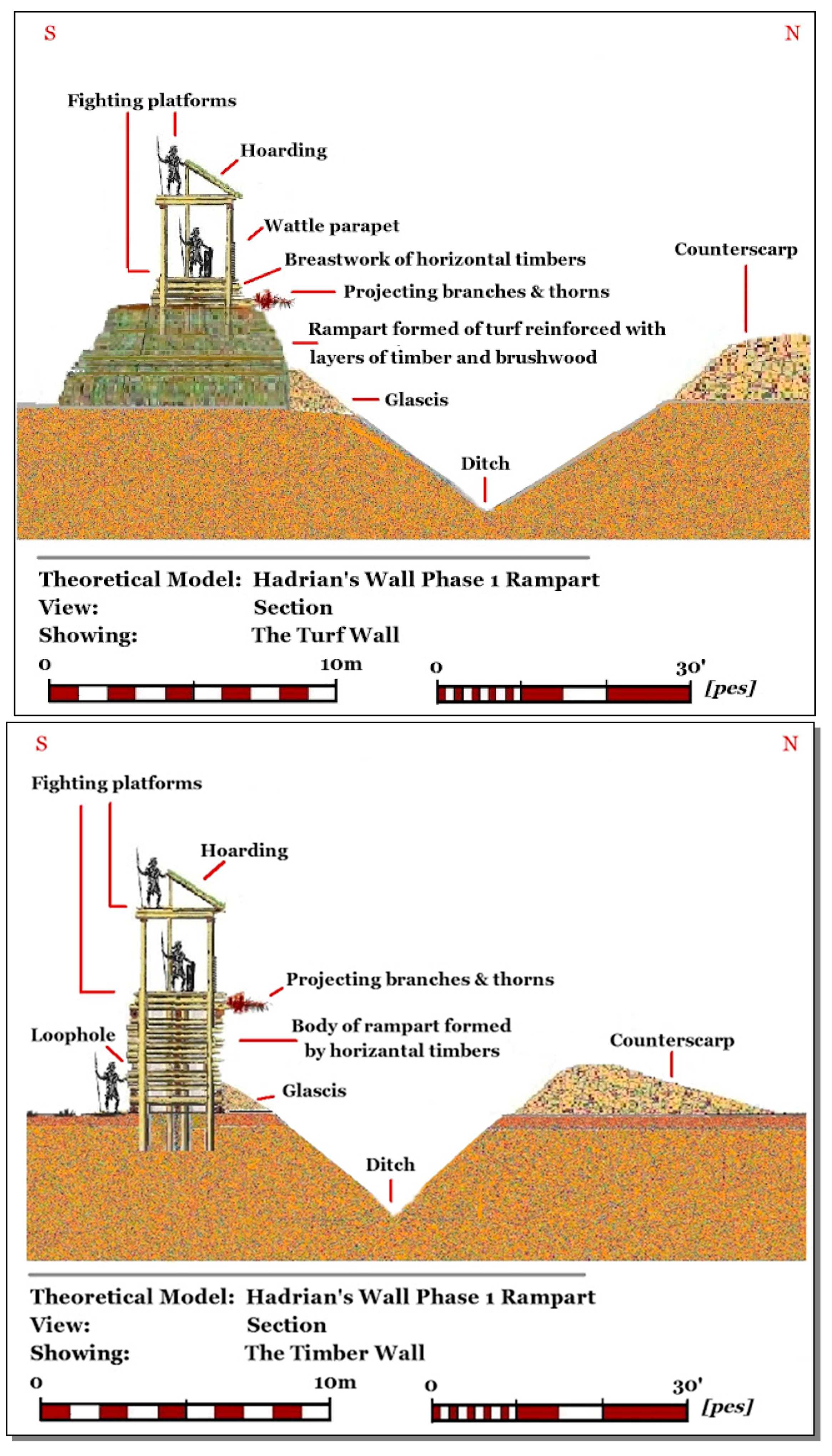

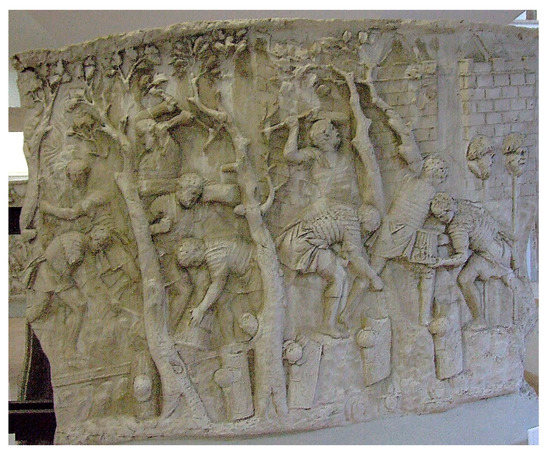

- The agricultural hinterland that constituted the town’s economic foundation and included the cultivation of crops and orchards. A visual illustration of this belt, although from biblical times, is evident in the Lachish relief (see Figure 1) that embellished the walls of a room in Sennacherib’s castle at Ninveh (704–681 BC). The relief realistically portrays the conquest of Lachish in 701 BC by the Assyrian army and in the background it is possible to see crops typical of Eretz Israel, which grew in the agricultural hinterland outside the city: vines, figs, olives, and palm trees (Amar 1999; Kislev 2000).

Figure 1. Agricultural hinterland outside the city Lachish, Lachish relief, Sennacherib’s castle at Ninveh.

Figure 1. Agricultural hinterland outside the city Lachish, Lachish relief, Sennacherib’s castle at Ninveh.

According to Yehuda Felix, a scholar who explored Talmudic botany and agriculture, many areas throughout Eretz Israel that were previously covered by forests and shrubs were cleared in rabbinical times and the cultivated area surrounding the towns was extensive (Felix 1991). With regard to Jerusalem, from the Hellenistic period on many agricultural settlements were established around the city and there is historical and archeological evidence of commercial and industrial ties between the city and these peripheral settlements (Baruch 1999).

- C.

- The external belt—an extensive uncultivated area of natural vegetation and sparse plant cover, designated “desert” (midbar) in Jewish sources (Ha-Reuveni 1991). Michael Zohary, one of the most prominent Israeli botanists in recent decades who reconstructed the ancient natural vegetation around Jerusalem, states that it was comprised of the next plants communities: of an oak and terebinth thicket, with woods of Jerusalem pines, and almond trees and hawthorns. The thicket and woods included many species of secondary plants, bushes, shrubs, and herbs (Zohary 1957). The flora that surrounded the city was a natural resource utilized for heating, cooking, and building, and sheep grazed among the vegetation.

Aside from these zones, Jerusalem had another belt that preceded the agricultural strip—a system of burial caves east of the city, in the Kidron stream. The graves were located outside the inhabited area for two major reasons. The first one is the ecological—the graves were located to the east to prevent hazardous odors, as the winds in Eretz Israel are western (Babylonian Talmud 1882, Baba Batra 25a; Har-Shefer 1994, p. 103). The second is religious reasons—laws of impurity and purity, i.e., maintaining a distance from sanitary hazards that might render the pilgrims and religious ritual items impure (Schechter 1945, p. 104). These norms are evidence of characteristics typical of a “holy city” whose spatial design was constructed following the physical outline of the expanse as well as theological needs.

2. “An Ecology of Holiness”: Cultivated Plants within the City Limits

Studies that explore the association between geography and religion show that the geographical and communal space of ancient holy cities was planned and designed following criteria or regulations that take account their special nature. For instance, in towns that served pilgrims, physical needs necessary for the absorption and congregation of large crowds, services provided to the pilgrims, and purification and hygiene facilities required for ritual preparation for the religious rites were taken into consideration (Peters 1986; Scott and Simpson-Housley 1991; Stoddard and Morinis 1997; Carmichael et al. 1997).

One of the manifestations of Jerusalem’s sanctity during the Second Temple period is an ecological regulation concerning the cultivation of plants in the inhabited area within the walls. This is one of ten regulations whose authors are unspecified, as are details concerning precisely when they were introduced or whether perhaps they developed over time.

The Tosefta2 is the most ancient Eretz Israel source to encompass reports on regulations restricting agricultural activity within the city limits. It states,

[Jerusalem] may not be planted nor sown nor plowed and no garbage dumps may be maintained in it and no trees may be maintained, aside from the rose garden that was there from the time of the first prophets, and no garbage dumps may be maintained in it for reasons of impurity and no projections (zizin) or balconies (gezuztraot, from Greek: ἐξώστρα [exostra] = an upper chamber. See: Smith et al. 1890, E.4.exostra-cn) may intrude into the public domain for reasons of tent impurity.(Tosefta, Negahim 6: 2, Zuckermandel 1937, p. 625)

The prohibition against growing plants in the city is also mentioned in Avot de-Rabbi Natan with a slight change.

And no plantings may be made in it. And no gardens and orchards may be made aside from the rose gardens that have been there from the time of the first prophets.(Schechter 1945, p. 104)

This version does not mention the prohibition against sowing and plowing, but these are included in the term “garden” (gina), which in rabbinical literature means a vegetable garden in which species of vegetables are cultivated using intensive irrigation (Löw 1934, vol. IV, pp. 255–60; Felix 1991, pp. 287–89). Avot de-Rabbi Natan is a supplement to Tractate Avot, estimated to have been written and redacted in the time of the Geonim, the rabbis of the early medieval era, sixth to eleventh centuries CE. Menachem Kister, who explored the redaction and versions of Avot de-Rabbi Natan, concluded that the tractate may indeed be of tannaitic origins, but the version we have before us underwent so many fundamental redactions over the years that it is hard and sometimes impossible to estimate its original form (Kister 1998). In any case, in this instance there are no extensive changes that reflect a radically different version of the regulation.

In addition to the prohibition against tending plants, the Tosefta provides information on two other ecological bylaws aimed at keeping sanitary hazards at a distance. These concerned “garbage dumps,” i.e., places for collecting and accumulating garbage, and projections and balconies protruding from buildings. In both cases, the official reason given for the prohibition is religious, i.e., problems involving impurity. The Tosefta explains that intrusions or deviations from the walls of buildings might cause those passing under them to become impure (“tent impurity”), while pilgrims headed for the temple to offer sacrifices were required to maintain their purity. The archeological find indicates that, in practice, from the mid-first century BCE until the destruction of the Second Temple the garbage produced in the city of Jerusalem was indeed collected outside the city walls, on the western bank of the Kidron stream (Reich and Shukron 2003; Weiss et al. 2006; Bar-Oz et al. 2007; Gadot 2018).

According to the reason brought in the Babylonian Talmud (1882, Baba Kama 82b), the prohibition against maintaining garbage dumps within the city was because they breed vermin, which might render the pilgrims and the offerings impure. In rabbinical times, dead animals or those that had been slaughtered and found ritually unfit were thrown into the garbage (Tosefta, Shekalim 3: 10, Lieberman 1955, p. 215), but the Tosefta does not state this explicitly. Keeping garbage dumps at a distance from the inhabited part of the city gave it a more respectable image, and it is not impossible that this too was part of the regulation’s underlying rationale.

Avot de-Rabbi Natan and the Babylonian Talmud speak of other bylaws that relate specifically to Jerusalem, such as the prohibition against establishing furnaces (see below) or raising chickens, geese, and pigs, as these rummage in the garbage and might transfer vermin in their mouth and thus render the flesh of the sacrifices impure (Schechter 1945, p. 104; Baba Kama 82b). According to the Greco-Roman literature, Mishnah and Talmud sources, and the abundance of Domestic Fowl (Gallus gallus domesticus) bones remains, chickens were common and important livestock in the economy of ancient Israel (Bouchnick et al. 2010; Perry-Gal et al. 2015a, 2015b). The prohibitions against maintaining garbage dumps and raising chickens in Jerusalem, with their distinctly religious grounds, are examples of a convergence point between purity and hygiene, i.e., religious regulations that contributed to maintaining the city’s health and clean environment (Devorzatzki 1999). In the next few lines, I shall focus on the landscape-ecological aspect of the regulations.

2.1. The Ecological Prohibition against Growing Plants within the City Limits of Jerusalem

As stated above, the designated areas for growing extensive produce and crops in ancient times were outside the city walls, but ownerless land and large yards within the city also were utilized for growing trees or vegetables. The Talmudic literature includes descriptions of yards that contained fig trees and vines as well as herbs (Mishnah Ma’asrot 2: 5; Mishnah Ma’asrot 3: 6; Tofefta Ma’asrot 2: 20, Lieberman 1955, p. 236; Jerusalem Talmud 1523, Ma’asrot 3: 4, 51a, and at length Kosman 1998).

The Tosefta does not state the purpose of the prohibition against growing plants in Jerusalem. The Babylonian Talmud, written about three hundred years later, says that the reasons for the ban against growing plants (excluding roses) is “due to the stench” (Babylonian Talmud 1882, Baba Kama 82b; Erkin 32b). The basis of the bad odor caused by growing plants within the city was not clarified in rabbinical literature, and this received several later interpretations. R. Shlomo Yitzhaki (Rashi, Troyes, Champagne, northern France, 1040–1105), one of the medieval Talmudic commentators, thinks that fertilizing gardens using animal manure spread bad odors or that garden owners disposed of weeds in the public domain. The vegetative waste would rot, develop a bad odor, and contaminate the city’s open areas (Rashi on Baba Kama 82b).

Since no religious explanation or justification was found for this regulation in Jewish sources, it appears to have been a distinctly ecological regulation. It is not impossible that the Sages were worried about crops whose products involved the spreading of bad odors, such as flax, a major crop in Eretz Israel in rabbinical times (Felix 1976, pp. 279–84; Kroiss 1924, vol. B/2, pp. 56–69). When flax stalks are processed to produce fibers, they are soaked in water for several days. The rotting of the green matter in the stalk produces bad odors, and the negative effects of this practice was documented in several sources (Hershberg 1924, pp. 71–78).

Rabbinical literature includes a list of ecological laws aimed at regulating life in a shared urban setting (Zichel 1990; Rakover 1993; Har-Shefer 1994). Such a distinctly ecological regulation is not known in the context of any other city in ancient Eretz Israel aside from Jerusalem. A similar municipal procedure pertaining to Jerusalem was the daily sweeping of the city’s markets, due not only to the many people that passed through them but also to the concentration of thousands of beasts and birds within the city limits and in the Temple, which made it necessary to deal with the considerable excretions of these animals, a source of stench and litter (Pesachim 7a).

The ecological regulations were introduced because the ancient leaders wished to give Jerusalem an aesthetic and clean municipal image as the “flagship” of the Jewish settlement in Eretz Israel and in the Diaspora and particularly due to the crowds that arrived in the city on the three pilgrimage festivals. According to the Babylonian Talmud, Bava Kama 82b, the concern for Jerusalem’s beauty, as well as for the well-being and welfare of the many pilgrims that flocked to it, was also manifested in additional bylaws.

- A prohibition against maintaining lime furnaces, located for ecological reasons next to the walls, so that their smoke would not blacken the stones. Interestingly, in rabbinical times care was taken in private homes as well to keep the whitewashed walls from becoming sooty and black (when people cooked or used fire for heating purposes) and sooty walls were an indication of extreme poverty and need (Safrai 1983, pp. 58–59).

- A prohibition against protruding projections and balconies, so that the pilgrims would not bump into them and be hurt. In contrast to the Tosefta, which explains these regulations as based on religious reasons, according to the Babylonian Talmud that they have distinctly ecological justifications.

The prohibition against projections protruding into the public domain is an ecological bylaw instituted in the Mishnaic period for all Jewish towns in Eretz Israel: “One may not extend projections or balconies into the public domain. Rather, if he desired [to build one he may] draw back into his [property by moving his wall], and extend [the projection to the end of his property line]” (Mishnah, Baba Batra 3: 8, compare to Rashi explanation: “so that they will not trip up people in the public domain”). Thus, also the regulation of keeping furnaces at least fifty cubits (c. 25 m) away from the city due to smoke and odor nuisances applies to all cities (Tosefta, Baba Batra 1: 10, Lieberman 1955, p. 131).

These two restrictions may have been emphasized in the case of Jerusalem as a holy city that houses many local residents and pilgrims, resulting in a greater risk of harm due to the crowding and congestion. Notably, many of the pilgrims did not find accommodation in organized hostels and therefore slept in the streets and open areas. When the city streets became full many were compelled to live in a tent city that evolved around the city, apparently in designated camping areas for this purpose (Mishnah, Bikurim 3: 2; Josephus 1895a, Antiquities of the Jews, book 17, chp. 9, sct. 3; Josephus 1895b, The Wars of the Jews, 2, 3, 1; Safrai 1965, p. 135). In a state of high congestion, there was a greater risk that low balconies and projections would pose a danger to the pilgrims.

In summary, both Eretz Israel and Babylonian sources see the prohibition against growing plants in the city as an ecological rather than religious regulation. According to the explanation in the Talmud, the purpose of the regulation was to prevent undesirable odors or litter and thus maintain the city’s respectable image.

2.2. Rose Gardens in Second Temple Jerusalem

According to the Tosefta, the prohibition against growing plants within the city did not apply to the ancient rose garden that had been there from the time of the first prophets, however according to the wording in Avot de-Rabbi Natan there were several rose gardens rather than only one (Schechter 1945, p. 104). The reason that the continued existence of these ancient gardens was permitted is not elucidated in the text. It may have stemmed from the ancient tradition of their cultivation in the city, leading to the conclusion that the rose industry could not be expanded to other gardens in the city.

Rashi in his commentary on Bava Kama 82b claimed that the Sages permitted the continued existence of the rose gardens because roses are identified with kipat hayarden, mentioned in baraita in Kritut 6a as one of the ingredients used in the Temple’s ritual incense (Löw 1934, vol. IV, p. 100; Chizik 1952, pp. 235–36; Felix 1976, p. 232). In other words, permission to maintain rose gardens was given for practical reasons, due to the need for the rose’s aromatic petals in order to prepare the incense. Kipat hayarden was identified as consisting of a list of aromatic substances such as amber with animal inclusions. In practice, its identification with roses is not sufficiently established and therefore it is hard to indicate a clear connection between growing roses in Jerusalem and the incense ritual (Amar 2002, pp. 145–49).

Rabbinical literature indicates that in the Sages’ time roses were cultivated for beauty and decoration, perfume, and for culinary purposes (Mishnah, Ma’asrot 2: 5; Mishnah, Sabbath 14: 4; Felix 1997, pp. 62–72). As stated by M. Kislev, species of aromatic, pretty, and colorful roses were developed as early as ancient times (Kislev 1997). It may be suggested that the permission to continue maintaining rose gardens stemmed from ecological reasons, i.e., their contribution to aesthetics and to improving bad odors in a crowded city.

2.3. Refraining from Growing Plants in the City: Following Roman Influence?

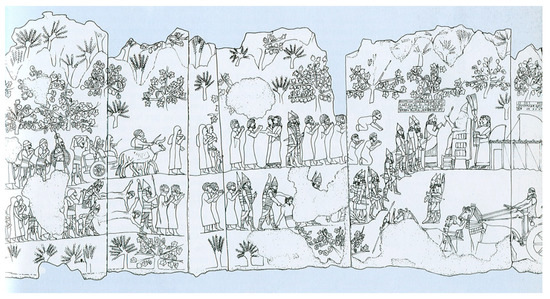

The inclination to restrict plant growing in the urban zone may be related to spatial, ecological, and aesthetic conceptions originating from the Roman world. The polis was ruled independently and encompassed mainly constructed and planned landscapes. These included streets, squares, public buildings (theatres, baths), and others. Cities were comprised of tall buildings and narrow streets and were densely populated (Ward-Perkins 1974, pp. 27–36; Hodge 1977; Grimal 1983, pp. 10–76). The huge cities typical of the Roman Empire, such as Rome, encompassed the private homes of the rich (domus) and multistory houses built close together (insulae).

In rural regions, wealthy peoples could surround their villa with terraced gardens. Within the city, rich Romans created their gardens inside the domus, in the peristylium, an open courtyard within the house surrounded by columns (Kluckert 2000, p. 17). The garden-flowers included violets roses, crocus, narcissus, lily, gladiolus, iris, and others (Smith 1875, p. 618; Kluckert 2000, p. 15). In the insulae climbing plants were intertwined on some of the balconies and porticos, and the windows were full of potted plants that appeared to resemble flowering gardens (Smith 1875, p. 619). It may be assumed that this design was intended to make up for the lack of space available for planting in the crowded polis.

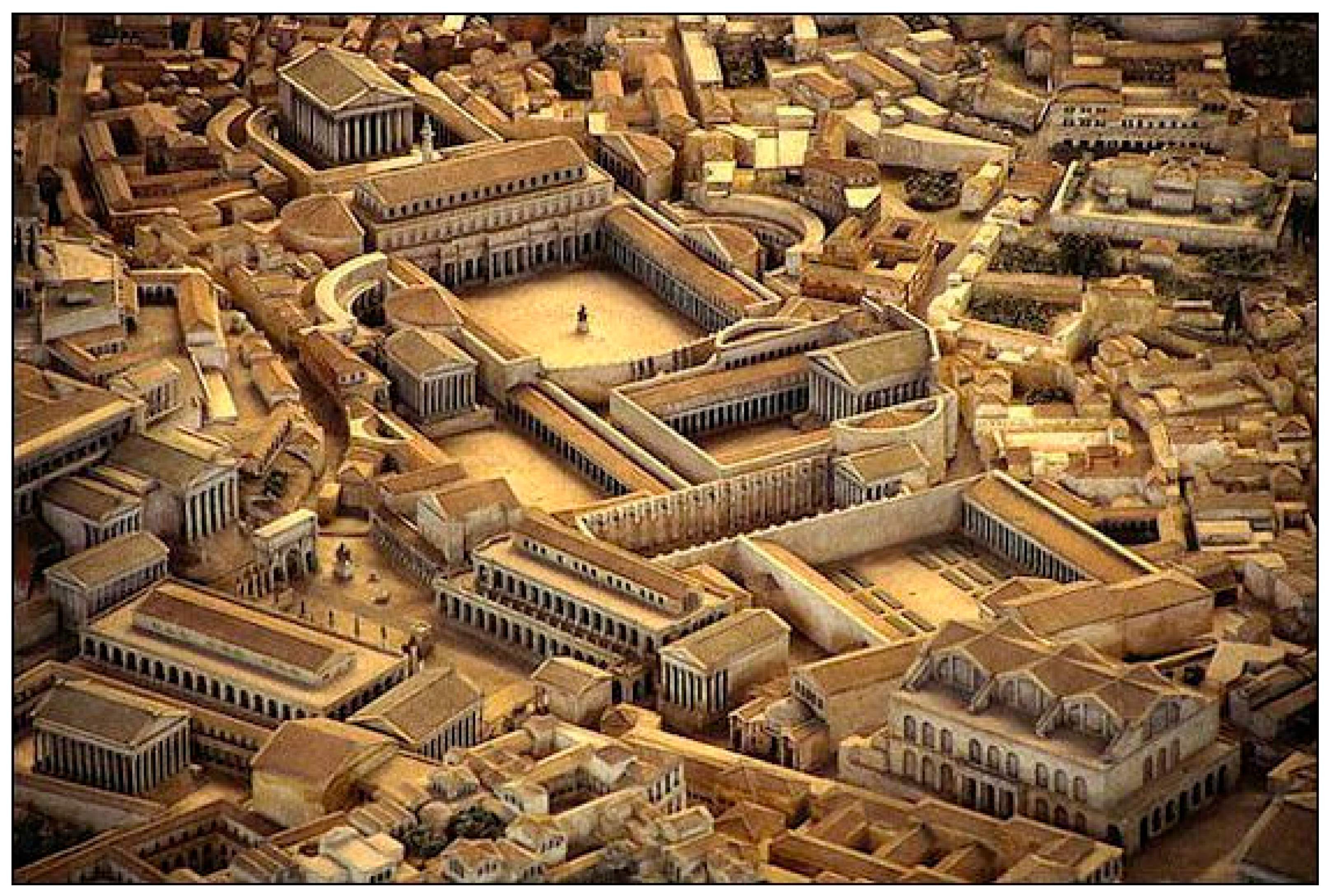

Archeologist Yoram Tsafrir states that, in contrast to our time when the vegetative land cover of urban areas is perceived as essential, the Roman perception was the exact opposite. He writes, “The designers of the Roman city did not allocate open green areas for the well-being of the residents, as customary today. The landscape visible to the residents was mainly a splendidly constructed and well-planned landscape” (Tsafrir 1988, p. 65), see Figure 2. The saturated construction of the city, with no allocation of green areas, was perceived by the architects of the Roman city as an aesthetic public space that represented their engineering skills and imperial power.

Figure 2.

A model of Ancient Rome: The fully saturated built landscape of the city. Source: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/525654587726903551/.

As stated, the Tosefta, composed in the second century AD, gave no reason for the prohibition, and the explanation that it was aimed at preventing bad odors originated from a later period. The Jerusalem-based sages in the Tannaitic period may have been affected by the Roman urban model customary in their time, i.e., a built-up polis-city. It is hard to know to what degree the prohibition against growing plants in Jerusalem was enforced in practice. In any case, it is clear that it was only relevant under Jewish rule and that, after the destruction of the Temple, the regulation lost all meaning.

In his book The Hasmoneans: Ideology, Archaeology, Identity, Eyal Regev discusses the Hasmonean palaces in Jericho and Herodian palaces. He investigates different architectonic features of the palaces—the swimming pools and gardens, the bathhouses, and the ritual bath [miqva’ot] (Regev 2013, pp. 246–54. On the places see also Netzer 2001). The Hasmonean royal palaces included few gardens. In addition to the small gardens in the courts of the Twin Palaces and the large garden north of the pool complex, there were two smaller gardens. These gardens were characteristic of Hellenistic palaces, probably due to Persian influence (Regev 2013, p. 248). Relying on comparisons with other Hellenistic palaces, especially the Herodian palaces, Regev concludes that “internal modesty and external propaganda” were characteristic of the Hasmonean palaces (Regev 2013, p. 263). Since the gardens were open spaces, they influenced visitors and outside observers. The public-facing nature of the Hasmonean gardens and Herod’s later use of pools and gardens was to demonstrate power and disseminated messages of political prominence. (Regev 2013, p. 249. On the power and influence, and political use made of gardens in by the Romans see Von Stackelberg 2009, pp. 73–85).

Regev’s conclusion provides a direct point of connection between the royal gardens and the roses gardens in Jerusalem mentioned in the Talmudic sources: people in the second temple period (citizens and pilgrims) may identify rose gardens in the holy city with wealth, power, and “civilized” urban life.

3. Vegetation of Jerusalem in Times of Decline

3.1. Destruction of the Agricultural Hinterland and Deterioration of the Natural Vegetation during the Great Revolt

The practice of destroying trees in times of war is reflected in the biblical law that forbids cutting down trees during lengthy sieges (Deuteronomy 20: 19–20). The Scriptures present live testimony of this destructive practice in the story of the Israelite war against Moab. It is related that, despite the biblical prohibition, the Israelites destroyed the Moabites’ agriculture and water infrastructure in order to detract from their combat readiness (2 Kings 3: 19). As stated by Paul Bentley Kern, the practice of cutting down trees in wartime had two reasons. The first was that trees had an important function for purposes of fighting and laying a siege (see below), and the second, more secondary reason was to intimidate the besieged by threatening them with famine and the severe economic crisis that might result from refusal to surrender (Kern 1999, p. 64.).

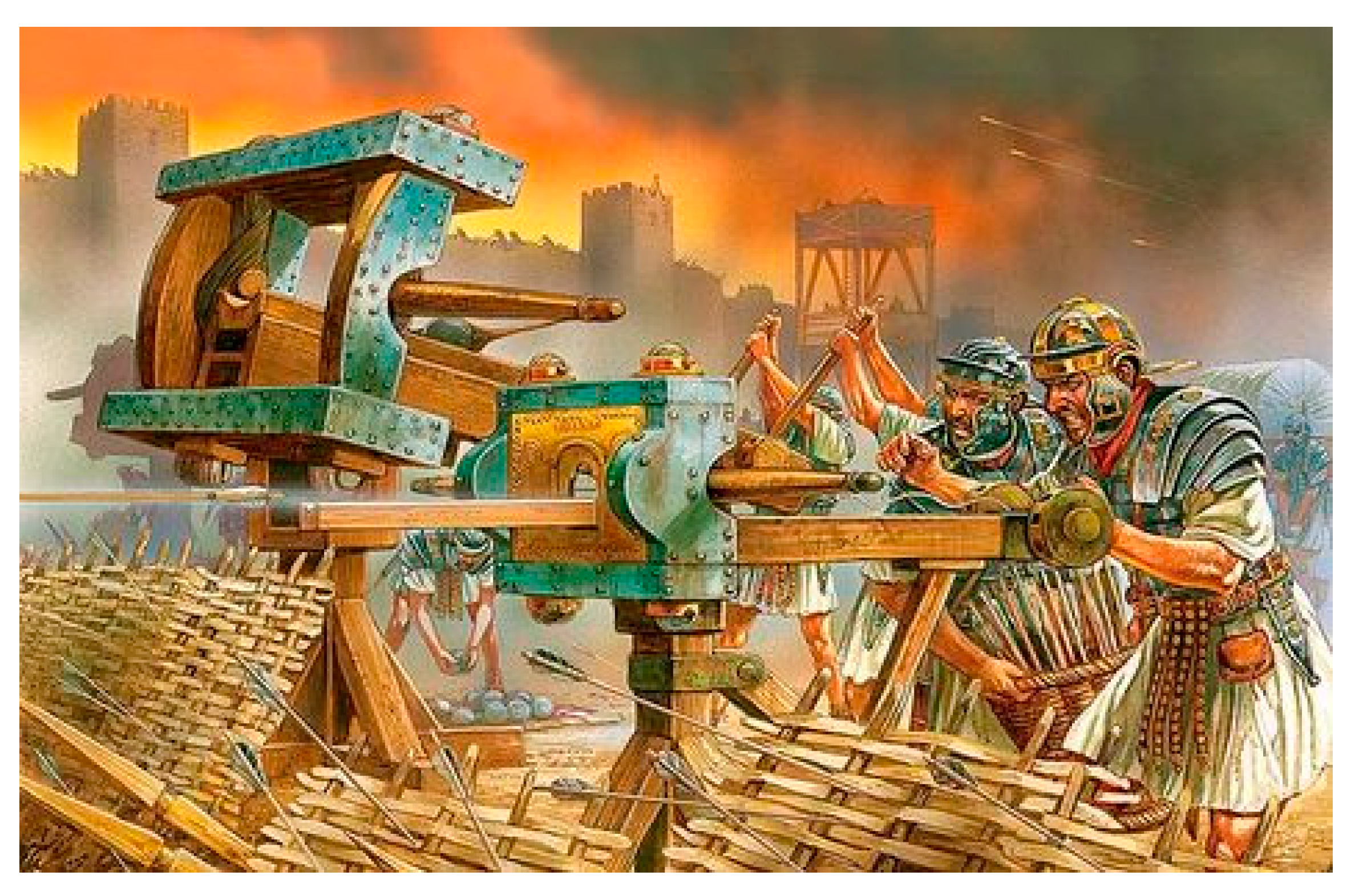

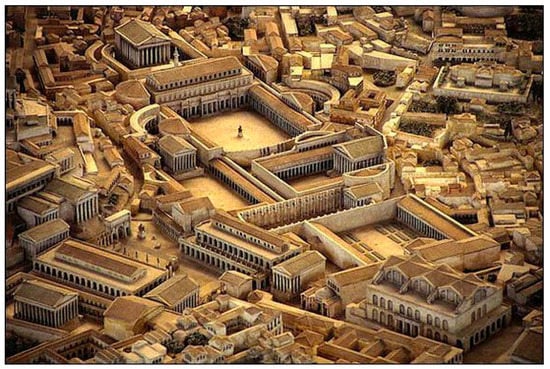

Harm to vegetation was caused not only by cutting down trees but also as a result of fires, whether planned or an outcome of the fighting. One combat tactic aimed at subduing a foreign army in open territory or overpowering a besieged city was to set it on fire by shooting burning arrows or using catapults (Figure 3). The policy of leaving “burned ground” was also customary. In these cases, after the city was conquered the besiegers burned it as punishment and revenge for the resistance of the besieged or so that the city would not be resettled and become a renewed center of unrest.

Figure 3.

Ancient Roman War: setting on fire the besieged city (illustration). Source: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/426082814722448278/.

The literature of the rabbinical period recorded the destruction of the vegetation in various opportunities. It is related that Caesar Adrian (76–138 CE) “devastated” the entire land and particularly the olive trees in the Galilee (Jerusalem Talmud 1523, Pe’a 7: 1). According to a tradition brought in the Jerusalem Talmud special units, called the King’s ketzi’ot, were charged with vandalizing trees during the war (Jerusalem Talmud 1523, Nedarim 3: 6, 38a). The meaning of the Hebrew word katza or kotza is to cut or to slice, i.e., units that cut down the trees during the battle (Mishnah Ma’asrot 2: 7; Sevi’it 8: 6’ Halla 2: 3; Even-Shoshan 1975, pp. 2386, 2389). As stated, here I shall focus on the harm inflicted upon the landscape in the Jerusalem region during the Great Revolt (66–70 CE).

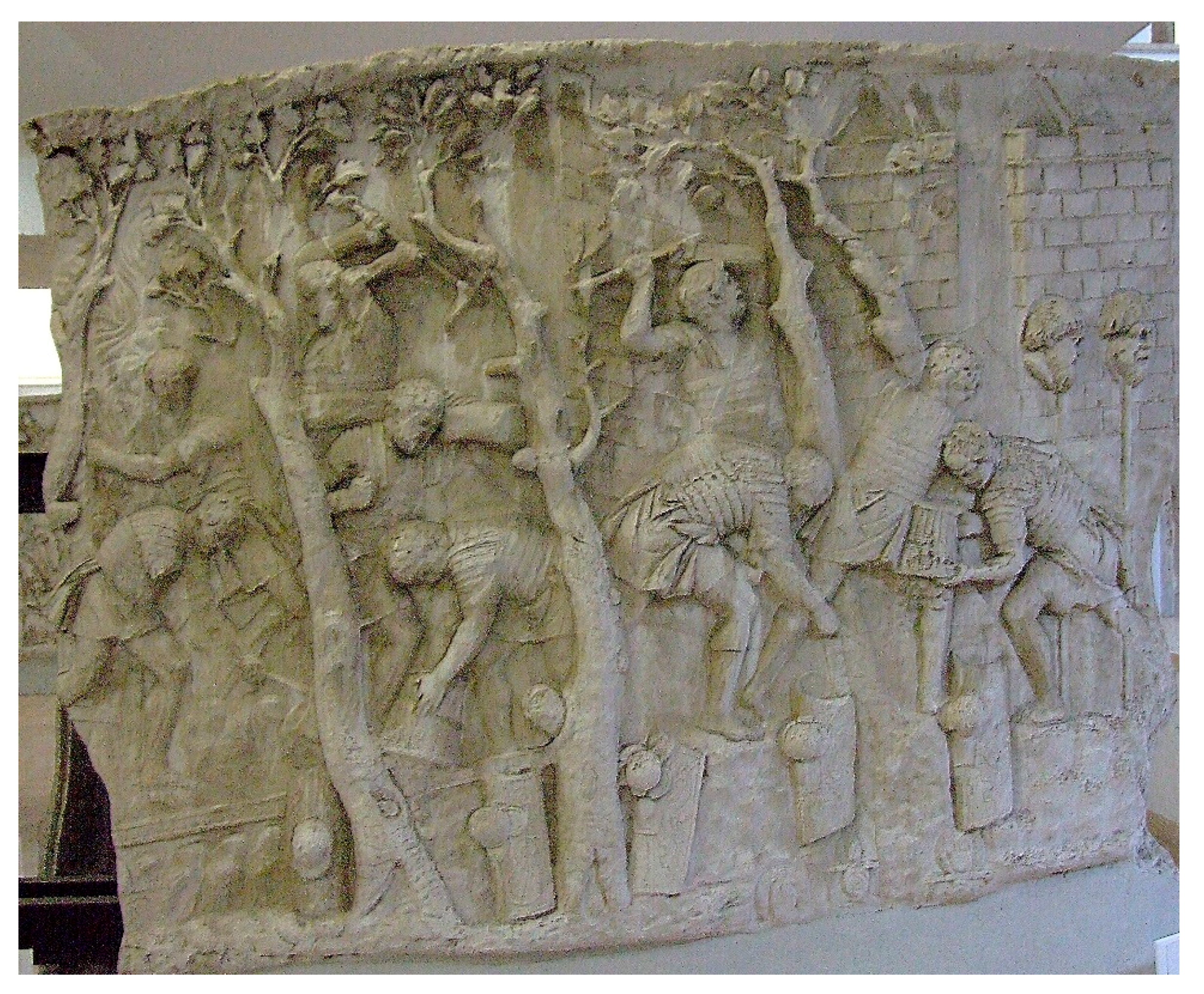

The conquering of Eretz Israel during the Great Revolt had a severe effect on the residential and agricultural infrastructure. Many towns and villages were burned and destroyed, whether in siege, attack, and conquest or in revenge and based on a policy of intimidation (Safrai 1982, pp. 18–20). The Jewish Transjordan and the Galilee were only slightly harmed during the Great Revolt, while Judah was more severely affected. Jerusalem was completely destroyed and many of its inhabitants killed (Rappaport 1984, pp. 274–302; Kasher 1983). In the process of the conquest, the natural plants and Jewish agriculture did not remain unscathed (Figure 4). The places most affected were those near which the Roman army was stationed for lengthy periods. Legio Fretensis (LXF), one of the most active legions in the battles for the city, was located in Jerusalem. During the siege on the city the legion encamped on Mt. Olives and after the war it was stationed as a garrison force within the city.

Figure 4.

Roman soldiers felling trees for construction purposes. From: Trajan’s Column. Source: Wikimedia commons.

Evidence of massive uprooting of trees during the Great Revolt and the destruction of the Second Temple exists in the writings of contemporary author Josephus Flavius (c. 37–100 CE), the first-century Jewish scholar, historian and hagiographer. Josephus recorded Jewish history, with special emphasis on the first century CE and the Jewish–Roman War in 66–70 CE, including the Siege of Masada. His most important works were The Wars of the Jews and Antiquities of the Jews.

The two testimonies cited below cited from The Wars of the Jews describe the destruction of agricultural crops as part of efforts by the Roman Legion headed by Titus (39–81 CE) to approach the city walls and subdue its inhabitants.

But Titus, intending to pitch his camp nearer to the city than Scopus, placed as many of his choice horsemen and footmen as he thought sufficient opposite to the Jews, to prevent their sallying out upon them, while he gave orders for the whole army to level the distance, as far as the wall of the city. So they threw down all the hedges and walls which the inhabitants had made about their gardens and groves of trees, and cut down all the fruit trees that lay between them and the wall of the city, and filled up all the hollow places and the chasms, and demolished the rocky precipices with iron instruments; and thereby made all the place level from Scopus to Herod’s monuments, which adjoined to the pool called the Serpent’s Pool.(Josephus 1895b, The Wars of the Jews Book 5, chapter 3, section 2)

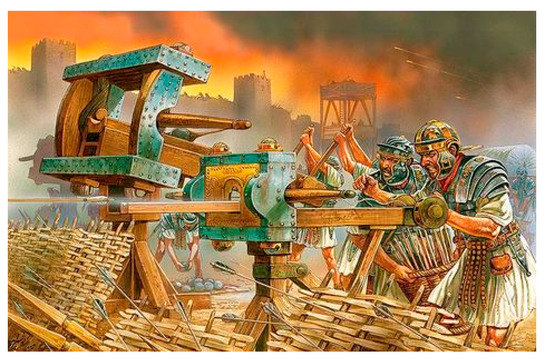

Further on in his portrayal of Jerusalem’s conquest, Josephus describes the construction of an additional rampart when the initial ramparts did not suffice.

He also at the same time gave his soldiers leave to set the suburbs on fire, and ordered that they should bring timber together, and raise banks against the city […] So the trees were now cut down immediately, and the suburbs left naked. But now while the timber was carrying to raise the banks, and the whole army was earnestly engaged in their works, the Jews were not, however, quiet.(Josephus 1895b, The Wars of the Jews 5, 6, 2)

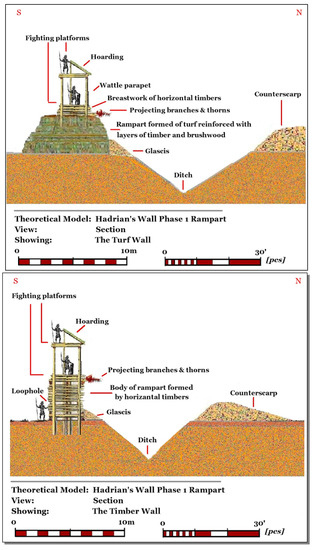

The first testimony refers to the uprooting of orchards relatively close to the wall in the area of the agricultural hinterland (see above) in order to straighten the gap between the low area of the Kidron stream and the eastern city wall. Since the two points are separated by dozens of meters, a large amount of rocks and vegetation was necessary. In the second testimony, Josephus continues to relate how Titus searched for another weak point in the wall and ordered his soldiers to create an additional rampart (Figure 5), such that removal of the fruit trees left the area near the wall desolate (on the use of rampart, towers and ditches in the Romans’ army tactic see Bidwell 2005).

Figure 5.

Reconstruction of two types of rampart (turf rampart and timer rampart), in Hadrian’s Wall (Vallum Aelium). Source:http://structuralarchaeology.blogspot.co.il/2011/12/hadrians-first-wall.html. (by permission of Geoff Carter. See: http://structuralarchaeology.blogspot.com/)

The most severe evidence of the grave ecological marks left by the fighting on the city’s vegetative landscape appears further on in his description of the campaign. According to Josephus, during the siege on Jerusalem all the trees around the city to a distance of 90 ris (c. 12 km) were cut down, such that at a later stage of the siege Titus had to bring trees from distant locations (Josephus 1895b: The Wars of the Jews 5, 12, 4). According to the descriptions provided by Josephus, when the vegetation in the agricultural hinterland did not suffice for fighting purposes, the Roman soldiers reached the most distant vegetative belt, i.e., the natural vegetation beyond the agricultural zone. These distances illustrate the dimensions of the destruction and the extensive ecological harm to the vegetative land cover. Notably, Josephus’ descriptions do not refer to the legions’ use of local plants for everyday purposes. These include plants used to cook food for thousands of soldiers as well as wood for heating during the cold Jerusalem winter.

An ancient regulation from Mishnah and Tlamud period forbids the raising of behema daka (goats and sheep) in Eretz Israel due to the damage caused to the agricultural infrastructure (Mishnah, Baba Kama 7: 7; Tosefta, Baba Kama 8: 10–12, Lieberman 1955, p. 39). Some claimed that the reason for the regulation was socioeconomic, and that it aimed to encourage and stimulate agricultural activity during the Second Temple era, or according to another opinion after the destruction of the temple, as part of the regulations attempting to rehabilitate the Jewish agricultural infrastructure destroyed during the Great Revolt and the Bar Kochba Revolt (On the opinions concerning the background of the ban see at length: Buchler 1906, p. 193; Golak 1941, pp. 181–89; Ber 1952, pp. 1–55; Alon 1975, pp. 173–78).

3.2. The Acacia and Cinnamon Trees That Vanished as a Result of Jerusalem’s Destruction

Indications of the damage and environmental catastrophe during the period of the Temple’s destruction, and perhaps even the outcomes of the Bar Kochba Revolt (132–135 CE), are evident in two late Talmudic traditions. One tradition, brought in the name of R. Yochanan, the greatest Eretz Israel amora of the second generation (died 279 AD), voices hope for the rehabilitation of the flora (“shitim”) around the city of Jerusalem:

R. Yochanan said: Every Shita tree that was taken by the invaders from Jerusalem will be restored to it by the Holy One, blessed be He, in time to come, as it says, “I will plant in the wilderness the cedar, the Shita tree” [Isa. 41: 19], and ‘wilderness’ means Jerusalem, as it is written, “Zion is become a wilderness” [Isa. 64: 9].(Babylonian Talmud 1882, Rosh ha-Shanah 23a)

The term “shitim” in the Scriptures and in rabbinical literature refers to trees of the Acacia genus (Faidherbia albida, common names: Winter Thorn, Anna Tree). Aside from one species that grows in the Mediterranean area but not in Jerusalem, most of the Acacia species that grow in Eretz Israel are desert species and do not grow in Jerusalem. The word shita in this source, similar to the word erez, is used in Talmudic literature as a collective noun for all trees, both natural and cultivated, utilized in daily life for purposes of industry and building (Felix 1997, pp. 156, 237; Amar 2012, pp. 151–52).

R. Yochanan based his homily concerning the future renewal of the city’s flora on two verses from the Book of Isaiah that refer to the destruction and redemption of Jerusalem. On one hand, the prophet describes Jerusalem as a city that was transformed into a desert and wilderness following its conquest by the armies that besieged it, and on the other, he anticipates its rehabilitation through the renewed flourishing of the various trees that will grow in it. In this way, R. Yochanan uses an ancient prophecy in order to plant hope in the heart of his own generation. R. Yochanan lived many years after the Temple’s destruction, and the tradition he conveys attests to the deep memories of the ruin and destruction that had become entrenched in the historiography of the period.

Another tradition, which has an aggadic orientation, tries to endow Jerusalem with a metaphysical uniqueness by describing fantastic plants that allegedly grew in it in the past but disappeared as a result of its destruction. Rahabah, Babylonian amora from the city Pumpedita, who lived in the third generation, says in the name of his teacher, R. Juda, one of the greatest Babylonian amoraim in the second generation (Margaliot 2000, vol. II, pp. 163–64, 309–10) that

The [fuel] logs of Jerusalem were of the cinnamon tree, and when lit their fragrance pervaded the whole of Eretz Israel. However, when Jerusalem was destroyed they were hidden.

Although this tradition originates from Babylon, far from Eretz Israel, it reflects the distressing memory of the alleged vanishing of cinnamon trees from Jerusalem many years previously. The recurring element of cinnamon trees that grow in Eretz Israel and in Jerusalem, trees that were used as “goat food,” i.e., cheap and popular trees, exists in other midrashic sources as well (Ekha Rabbah 1885–1887, Petichta 10, Reem edition, p. 5; Song of Songs Rabbah 1885–1887, chp. 4: sct. 14, Reem edition, p. 57; Ester Rabbah 1885–1887, chp. 3: sct. 4, Reem edition, p. 12; Jerusalem Talmud 1523, Pe’a 7: 3, 20a). Ze’ev and Chana Safrai, in their article on the concept of the Eretz Israel’s sanctity and its development in rabbinical sources and in the Apocrypha, show how this element and other supernatural descriptions, such as the portrayal of the land as excessively productive, exaggerate the value and praise of Eretz Israel and of Jerusalem as part of the structuring and shaping of the sacred image of these spaces (Safrai and Safrai 1993, pp. 344–71).

Cinnamon trees (Cinnamomum sp.) grow in tropical parts of southern India, the Ceylon Islands, and China, but not in Eretz Israel (Zohary 1969, p. 157). Nonetheless, it is indeed true that when the bark of the tree is burned, it gives out an aroma similar to that of cinnamon due to its oil content. The tale goes that in 1760, a huge quantity of cinnamon was burned in Amsterdam (worth millions of guilders), and the pleasant aroma spread throughout Holland. The cinnamon was burned intentionally to maintain its high price (Löw 1934, vol. II, p. 109).

As a luxury spice and perfume, it was brought to Mediterranean countries by the maritime trade routes (Casson 1984, pp. 225ff.). Use of Cinnamomum cassia appears to have been more common in ancient times, while according to researchers, Cinnamomum zeylanicum was unknown in the Near East prior to the mid-13th century. Cinnamon is mentioned in rabbinical literature in different contexts, and it was also an ingredient in the ritual incense of the Temple (Löw 1934, vol. II, pp. 107–17; Felix 1997, pp. 101–12). The Talmudic tradition does not refer to the cinnamon of Jerusalem as an expensive ritual perfume rather describes it as a common local tree, one that the people of Jerusalem would burn in their ovens in place of regular firewood. However regrettably, following the destruction of the city, the trees “vanished.”

The exegetist explains the disappearance of cinnamon trees from the Jerusalem landscape as the result of their annihilation during the fighting and the city’s destruction. However, it appears that he wished to express another idea as well. The wonderful aroma that spread throughout Jerusalem when the wood of the cinnamon trees was burned indicates the city’s “spirituality.” The symbolic characterization of sacred sites and spaces by means of a fragrance is a common literary pattern in Jewish sources. One example is the description of the fragrance of the temple’s ritual incense that wafted to a great distance, reflecting the mystical impact of the Temple beyond its natural and realistic boundaries (Mishnah, Tamid 3: 8).

Moreover, as shown by researchers, pleasant fragrances in the context of Jerusalem indicate an association between the Garden of Eden and the Temple. The Garden of Eden is planted with aromatic fragrant trees, while the rituals in the Tabernacle and in the Temple include the incense offering (Bereshit Rabbah 1885–1887, chp. 33: sct. 6, Reem edition, p. 138; Kahana 1957, Adam and Eve Book, p. 13). Hence, the pleasant scent spread by the cinnamon trees enhance Jerusalem’s Garden of Eden atmosphere (Elior 2010, pp. 105–41; Mazor 2002, pp. 5–42). The exegetist wished to express the idea that following the destruction, as symbolized by the annihilation of the cinnamon trees, Jerusalem lost its lofty spiritual atmosphere.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Attempts at shaping the urban landscape by means of bylaws and changes in the vegetation surrounding the city of Jerusalem reflect transformations in the city’s status during the Roman period. The unique ecological regulations pertaining to Jerusalem versus other towns in Eretz Israel, and particularly the prohibition against maintaining gardens or plants aside from rose gardens, reflect the city’s religious sanctity and its status as a focus of mass pilgrimage. It is not known to what degree the regulations were implemented or enforced in practice. In any case, most of them clearly lost their significance after the destruction of the Temple and once Jerusalem passed into Roman hands.

The prohibition against growing plants in the city was explained in post-Mishnaic sources as aimed at preventing the stench of fertilization or rotting weeds from the fields. Preventing bad odors that constitute a sanitary nuisance contradicts the principle of sacred spaces as identified with spreading pleasant scents, since the aromatic fragrance that surrounds them expresses and attests to their holy atmosphere.

As stated by contemporary sages, the regulation forbade the maintaining of regular gardens, i.e., vegetable gardens, and growing trees. However, it was permitted to maintain a certain rose garden or, according to another version, rose gardens that had existed in the city for many generations previously. Some claimed that the permission to grow roses was given due to the need for flowers for purposes of the ritual incense, but it may also be suggested that the reason was based on aesthetic design. The magnificent rose bushes added color and beauty to the city and also helped improve the prevalent odors.

It may be assumed that the outlook in favor of pleasant odors in the city was also based on the imaginary description of the cinnamon trees as a component of Jerusalem’s vegetation that when burned in home ovens spread a pleasant fragrance throughout the city. In everyday life, extensive burning of wood creates a smoke and odor hazard, but in Jerusalem, things are different, as it is a metaphysical site. As we suggested, the pleasant scent of the cinnamon that enveloped the city may hint at the association between the Temple and the Garden of Eden, with its aromatic scents (“scent of the Garden of Eden”), and this element is reminiscent of the midrashic approach whereby the scent of the ritual incense had the effect of forming a pleasant odor in the city and even neutralized the smoke and the odor of the sacrifices burning in the Temple.

Justification of the prohibition against growing plants as preventing bad odors appeared in the Talmudic literature some three hundred years after the regulation was recorded in the Tosefta. The later explanation may be based on a tradition that was conveyed over the generations, but it may also be associated with concepts concerning the design of urban space. We propose that the Jerusalem-based sages in the Tannaitic period were affected by the ideal Roman urban model customary in that period, i.e., a polis-city that consisted mainly of buildings and had less of a rural and agricultural nature.

The regulations aimed at preventing damage to the urban zone, with the exception of growing roses in gardens for aesthetic reasons, stem from the understanding that Jerusalem is a holy and honorable city. Moreover, this city is a center of attraction for many pilgrims that fill its streets three times a year. Such a city must offer pilgrims a pleasant site, and its ecology must support the religious experience. Various nuisances, such as unpleasant smells and litter, are detrimental to those visiting and to the city’s image.

The city’s aesthetics reflect its spirituality and prosperity. Then again, tragic events such as the Great Revolt had a grave effect on the landscape surrounding the city and left it deserted and desolate. During the siege on the city, the Roman army inflicted severe damage on the agricultural belt around the city and even on more distant areas. Trees were used by the army for purposes of the siege (to build ramparts), but as stated above, there were also other reasons such as revenge and to devastate the city’s agricultural-economic infrastructure. Destroying the vegetation was also perceived in Jewish sources as having religious significance. The disappearance of the cinnamon trees from view as a result of the city’s destruction was perceived as ravaging the city’s supernatural atmosphere, similar to the acacia trees “taken by the non-Jews” from Jerusalem. The future rehabilitation of the landscape through its reinstatement by G-d will indicate both the rehabilitation of the physical infrastructure and the city’s reshaping as a holy space.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alon, Gedalya. 1975. The History of the Jews in Eretz Israel in the Mishnaic and Talmudic Period. Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad. [Google Scholar]

- Amar, Zohar. 1999. Agricultural Products in the Lachish Relief. Beit Mikra 159: 350–56. [Google Scholar]

- Amar, Zohar. 2002. The Book of Incense. Tel Aviv: Eretz. [Google Scholar]

- Amar, Zohar. 2012. The Plants of the Bible. Jerusalem: Reuven Mass. [Google Scholar]

- Babylonian Talmud, 1882, Vilna ed. Vilna: Reem.

- Bar-Oz, Guy, Ram Bouchnik, Ehud Weiss, Lior Weissbrod, Daniella E. Bar-Yosef Mayer, and Ronny Reich. 2007. “Holy Garbage”: A Quantitative Study of the City-Dump of Early Roman Period Jerusalem. Levant 39: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Eyal. 1999. The Agricultural Hinterland of Jerusalem during the Herodian Period. Cathedra 89: 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ber, Yitzhak. 1952. The Historical Foundations of the Halakha. Zion 17: 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bereshit Rabbah. 1885–1887. Vilna: Reem.

- Bidwell, Paul T. 2005. The systems of obstacles on Hadrian’s Wall: their extent, date and purpose. Arbeia Journal 8: 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchnick, Ram, Guy Bar-Oz, and Ronny Reich. 2010. On the Importance of Poultry in the Animal Economy of Judea in the Late Second Temple Period. New Studies on Jerusalem 16: 119–40. [Google Scholar]

- Buchler, Abraham. 1906. Der Galilaische Am-ha-Ares, Des Zweiten Jahrunderts. Wien: Holder. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, David L., Hubert Jane, Reeves Brian, and Schanche Audhild, eds. 1997. Sacred Sites, Sacred Places, One World Archaeology. London: Routledge, vol. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Casson, Lionel. 1984. Ancient Trade and Society. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chizik, Baruch. 1952. Otsar ha-Tsmahim [=A Treasury of Plants]. Herzlia: Chizik, Baruch. [Google Scholar]

- Devorzatzki, Esti. 1999. The Public health in Jerusalem in the Second Temple Period. In The Medicine in Jerusalem through the Ages. Edited by Efraim Lev, Zohar Amar and Joshua Schwartz. Tel Aviv: Eretz, pp. 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ekha Rabbah. 1885–1887. Vilna: Reem.

- Elior, Rachel. 2010. Paradise, the Holy of Holies and tabernacle. In Gan be-Eden Mi-Kedem: Traditions of Paradise in Israel and the Nations. Edited by Rachel Elior. Jerusalem: Magnes, pp. 105–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hershberg, Abraham Samuel. 1924. The Cultural Life in the Period of the Mishnah and Talmud: The fabric and the Fabric Industry. Warsaw: Abraham Joseph Shtibel. [Google Scholar]

- Ester Rabbah. 1885–1887. Vilna: Reem.

- Even-Shoshan, Abraham. 1975. The New Dictionary. Jerusalem: Kiryat Sefer. [Google Scholar]

- Felix, Yehudah. 1976. The World of the Biblical Plants. Ramat Gan: Massada. [Google Scholar]

- Felix, Yehudah. 1991. Agriculture in Eretz-Israel in the Period of the Bible, Mishnah and the Talmud. Jerusalem: Reuven Mass. [Google Scholar]

- Felix, Yehudah. 1997. Trees: Aromatic, Ornamental and of the Forest, in the Bible and Rabbinic Literature. Jerusalem: Reuven Mass. [Google Scholar]

- Gadot, Yuval. 2018. Jerusalem and the Holy Land(fill). Biblical Archaeology Review 44: 36–45, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Gafni, Isaiah. 1999. Jerusalem in Sage Literature. In Jerusalem Book: The Roman and Byzantine Period, Jerusalem. Edited by Yoram Tsafrir and Samuel Safrai. Jerusalem: Yad Yitzhak ben Zvi, pp. 35–59. [Google Scholar]

- Golak, Asher. 1941. On Shepherds and Breeding Small Cattle in the Destruction of the Second Temple Period. Tarbiz 12: 181–89. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, Martin. 1999. The pilgrimage economy of Jerusalem in the Second Temple period. In Jerusalem, Its Sanctity and Centrality to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Edited by Lee I. Levine. New York: Continum, pp. 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Grimal, Pierre. 1983. Roman Cities. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ha-Reuveni, Noga. 1991. Desert and Shepherd in Israel Heritage. Givatime: Neot Kedumim. [Google Scholar]

- Har-Shefer, Zvi. 1994. Ecology in Jewish Heritage. Haifa: Sha’anan College Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, Peter. 1977. Aspects Romans Life: Roman Towns, 2nd ed. London: Addison-Wesley Longman Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, Ian W. 1980. The City Region in Roman Palestine. PEQ 112: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huot, Jean-Louis. 1999. The Archaeology of Landscape. In Landscapes—Territories, Frontiers and Horizons in the Ancient near East. Edited by Lucio Milano, Stefano de Martino, Frederick Mario Fales and Giovanni Battista Lanfranchi. XLIV RLI (Part 1 Invited Lectures). Padova: Sargon, pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jerusalem Talmud, 1523, Venice ed. Venice: Daniel Bomberg.

- Josephus, Flavius. 1895a. Antiquities of the Jews. In The Works of Flavius Josephus. Translated by William Whiston. Auburn and Buffalo: John E. Beardsley. [Google Scholar]

- Josephus, Flavius. 1895b. The Wars of the Jews. In The Works of Flavius Josephus. Translated by William Whiston. Auburn and Buffalo: John E. Beardsley. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana, Abraham. 1957. Apocrypha. Tel Aviv: Masada, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Kasher, Arye. 1983. The Great Jewish Revolt: Factors and Circumstances Leading to Its Outbreak. Jerusalem: Merkaz Zalman Shazar. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, Paul Bentley. 1999. Ancient Siege Warfare. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kislev, Mordechai. 1997. Garden of Roses. Sinai 120: 128–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kislev, Mordechai. 2000. The Sycamores in Lachish Reliefs—Identification according to Sages Words. In Jerusalem and Eretz-Israel: Arie Kindler Book. Edited by Joshua Schwartz, Zohar Amar and Irit Tzifer. Ramat Gan and Tel Aviv: The Ingeborg Rennert Center for Jerusalem Studies and Eretz Israel Museum, pp. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kister, Menachem. 1998. Scrutinizing in Avot de-Rabbi Nathan: Version, and Commentary, Editing. Jerusalem: Yad Yitzhak ben Zvi and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. [Google Scholar]

- Kluckert, Ehrenfried. 2000. European Garden Design: From Classical Antiquity to the Present Day. Bonn: Könemann. [Google Scholar]

- Kosman, Admiel. 1998. The House, the Garden, the Yard and the Menagerie in Sages’ Period. Asufot 11: 151–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kroiss, Samuel. 1924. Antiquity of the Talmud. Tel Aviv-Berlin and Vienna: Benjamin Hertz, vol. B/2. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Lee I. 1984. Jerusalem—The City and the Temple in the End of the Second Temple period. In The History of Eretz Israel, Vol. 4: The Roman Byzantine Period, the Roman Period from the Conquest to the Ben Kozba War (63BC–135CE). Edited by Menachem Stern. Jerusalem: Keter, pp. 171–93. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Lee I. 2002. Jerusalem: Portrait of the City in the Second Temple Period (538 BCE–70 CE). Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, Saul. 1955. Tosefta. New York: Jewish Theological Seminary. [Google Scholar]

- Löw, Immanuel. 1934. Die Flora der Juden. Vienna-Leipzig: R. Löwit, vols. I–IV. [Google Scholar]

- Margaliot, Mordechai. 2000. Encyclopedia of Talmudic and Geonic Literature. Tel Aviv: Yavne and Sifre Hemed. [Google Scholar]

- Mazor, Lea. 2002. The bi-directional Connection between Paradise and the Temple. Shnaton—An Annual for Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies 13: 5–42. [Google Scholar]

- Netzer, Ehud. 2001. Hasmonean and Herodian Palaces at Jericho: Final Reports of the 1973–1987 Excavations, Vol. 1: Stratigraphy and Architecture. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Perry-Gal, Lee, Adi Erlich, Ayelet Gilboa, and Guy Bar-Oz. 2015. Earliest economic exploitation of chicken outside East Asia: Evidence from the Hellenistic Southern Levant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112: 9849–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry-Gal, Lee, Guy Bar-Oz, and Adi Erlich. 2015. Livestock Animal Trends in Idumaean Maresha: Preliminary Analysis of Cultural and Economic Aspects. Aram 27: 213–26. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Francis E. 1986. Jerusalem and Mecca: The Typology of the Holy City in the Near East. New York: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rakover, Nahum. 1993. Environmental Issues, Theoretical and Legal Aspects of Jewish Sources. Jerusalem: Moreshet Hamishpat BeIsrael. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport, Uriel. 1984. A History of Israel in the Period of the Second Temple. Tel-Aviv: Amikhai. [Google Scholar]

- Regev, Eyal. 2013. The Hasmoneans: Ideology, Archaeology, Identity. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, Ronny, and Eli Shukron. 2003. The Jerusalem city-dump in the late Second Temple Period. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palastina-Vereins 119: 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Safrai, Samuel. 1965. Pilgrimage to Jerusalem in the Second Temple Period. Tel Aviv: Am ha-Sefer. [Google Scholar]

- Safrai, Samuel. 1982. The Recovery of the Jewish settlement in Yavneh Generation. In Eretz Israel from the Destruction of the Second Temple to the Muslim Conquest, Vol. I: Political, Social and Cultural History. Edited by Zvi Baras, Shmuel Safrai, Menahem Stern and Yoram Tsafrir. Jerusalem: Yad Yitzhak ben Zvi. [Google Scholar]

- Safrai, Samuel. 1983. At the End of the Second Temple and the Mishnaic Period: Chapters in the History of the Society and Culture. Jerusalem: The Office of Education and Culture and the Zalman Shazar Center. [Google Scholar]

- Safrai, Ze’ev. 2011. The Memory of the Temple: Indeed Memory of the Temple and for What? Innovations in Jerusalem’s Research 16: 255–302. [Google Scholar]

- Safrai, Ze’ev, and Chana Safrai. 1993. The Holiness of Eretz Israel and Jerusalem: Characteristics of development of Idea. In Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple, Mishnah and Talmud Period. Edited by Menachem Stern, Isaiah Gafni and Aron Openheimer. Jerusalem: Yad Yitzhak ben Zvi, pp. 344–71. [Google Scholar]

- Schechter, Shlomo Zalman. 1945. Avot de-Rabbi Nathan. New York: Feldheim, Also published in the version of Vienna 1887. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Joshua J. 1991. Lod (Lydda), Israel: From Its Origins through the Byzantine Period. BAR International Series 571; Oxford: Tempus Reparatum. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Jamie, and Paul Simpson-Housley, eds. 1991. Sacred Places and Profane Spaces: Essays in the Geographics of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. New York: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, William. 1875. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. London: John Murray, Available online: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/secondary/SMIGRA*/Hortus.html (accessed on 12 June 2018).

- Smith, William, William Wayte, and George Eden Marindin. 1890. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. London: John Murray, Available online: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0063%3Aalphabetic+letter%3DE%3Aentry+group%3D4%3Aentry%3Dexostra-cn (accessed on 15 June 2018).

- Song of Songs Rabbah. 1885–1887. Vilna: Reem.

- Stoddard, Robert H., and Alan Morinis. 1997. Sacred Places, Sacred Spaces: The Geography of Pilgrimages. Baton Rouge: Geoscience Publications, Department of Geography and Anthropology, Louisiana: Louisiana State University. [Google Scholar]

- Tsafrir, Yoram. 1988. Eretz Israel from the Destruction of the Second Temple to the Muslim Conquest, Vol. II: Archaeology and Art. Jerusalem: Yad Yitzhak ben Zvi. [Google Scholar]

- Von Stackelberg, Katharine T. 2009. The Roman Garden: Space, Sense, and Society. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Perkins, John Bryan. 1974. Planning and Cities: Cities of Ancient Greece and Italy—Planning in Classical Antiquity. New York: G. Braziller. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Ehud, Ram Bouchnick, Guy Bar-Oz, and Rony Reich. 2006. Garbage near the Temple: Some thoughts on the location of Jerusalem Second Temple period city-dump. In New Studies on Jerusalem 12. Edited by Eyal Baruch and Avraham Faust. Ramat-Gan: University of Bar-Ilan, pp. 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Zichel, Meir. 1990. Environmental (Ecological) Issues in Jewish Sources. Responsa Project. Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zohary, Michael. 1957. The Flora and Vegetation in Jerusalem Landscape. In Jerusalem Book. Edited by Michael Avi-Yonah. Jerusalem: Mossad Bialik and Dvir. [Google Scholar]

- Zohary, Michael. 1969. The World of Plants. Tel Aviv: Am Oved. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckermandel, Moses Samuel. 1937. Tosefta. Jerusalem: Bamberger and Wahrmann. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The Mishnah (“repeated study”) was redacted by R. Judah the Prince at the end of the second century CE. The Mishna is the first major written redaction of the Jewish oral traditions and laws. The Talmud (also Gemara, means “study” or “learning”) is a collection of commentaries on and elaborations of the Mishnah and certain auxiliary materials. The term “Talmud” refers to the Jerusalem Talmud (Talmud Yerushalmi) that was compiled in the Land of Israel (c. 400 CE) and the collection known as the Babylonian Talmud (Talmud Bavli), compiled by the scholars of Babylonia (c. 500 CE). |

| 2 | The Tosefta (“supplement,” “addition”) is a compilation of the Jewish oral law from the late second century CE, the Tanaitic era. The Tosefta compiled in Eretz Israel, and according to rabbinic tradition, it was redacted by the Tannaim R. Ḥiya and R. Oshaiah. Tannaim (“repeaters” or “teachers”) were the rabbinic sages whose views are recorded in the Mishnah and the Tosefta. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).