Abstract

When children lose a parent during childhood this offers emotional and life changing moments. It is important for them to be included in the death ritual and to be recognized as grievers alongside adults. Recent research has shown that children themselves consider it relevant to be part of the ‘communitas’ of grievers and do not like to be set aside because they are considered to be too young to participate. In this case study, I describe how a Dutch mother encouraged her three children, aged 12, 9 and 6, to participate in the death rituals of their father. She asked a funeral photographer to document the rituals. In that way, later on in their life, the children would have a visual report of the time of his death in addition to their childhood memories. The objective of my case study research was first, to explore in detail hów children are able to participate in death rituals in a carefully contemplated manner and in accordance with their age and wishes, and second, to examine the relevance of funeral photographs to them in later years. The funeral photographs will be presented as a visual essay of how and when the children took part in the rituals and which ritual objects, such as the coffin and the grave, but also letters, poems and drawings were important in creating an ongoing bond with their deceased father. The conclusion of this case study presentation is that funeral photographs of death rituals may function as mnemonic objects later on in the life of children who lost a parent in their childhood. These photographs enable children, when necessary, to materialize how they participated in the death ritual of their father or mother. In this respect they can be seen as functional means of continuing bonds in funeral culture, linking the past with the present, in particular when young children are involved.

1. Introduction

Remembering deceased family members by means of photographs is the leading theme in the 2017 Disney Pixar movie, Coco. Traditional Mexican death rituals, especially related to Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead), are presented in the movie. On this day, relatives come together and share stories about family members who have passed away. Ofrendas (homemade altars created in honor of dead family members) are decorated with valued photographs, favored foods and other objects symbolizing the life of the family members (Dakin 2017, p. 12; Disney PIXAR 2017, p. 35). The entire family, including young children, are involved in these traditional and culturally embedded rituals.Remember meThough I have to say goodbye1

The principal message of the movie, and the message that the main character, Miguel finally understands is that your family is at the center of your life, it offers security and a basis for development. Deceased ancestors still belong to the family and it is important to stay connected, to reach out to them: not having a photograph on the ofrenda means you are forgetting the particular family member. To Miguel, these photographs function as mnemonic objects as they help him in keeping the memory of his ancestors alive. Zerubavel describes these type of photographs as “physical mnemonic bridges”, as objects which create “tangible links between past and present.” (Zerubavel 2003, pp. 43–44) Obviously, Coco is fiction, and an animation movie for children, but it is interesting to see how Miguel seems to be at ease and comfortable with all matters related to death, particularly, when nowadays in many western countries with less traditional and culturally embedded death rituals, death is often a taboo subject when children are involved. Participation of children in the death ritual has diminished as Western attitudes towards death have changed (Ariès [1974] 1994; Søfting et al. 2016).

In the Netherlands in the twenty-first century, death has become a more publicly discussed subject in a variety of media, including scientific publications, but also media targeted towards the general public, for instance, in television programs or in glossy periodicals.2 However, it still remains difficult to discuss the subject with children even though educational materials have been developed and are distributed, for example by funeral directors. The Dutch Funeral Museum, ‘So Long’ has developed educational material for children, including an educational program for pupils at elementary schools. The objective is to lift the taboo and to offer tools to facilitate discussions with children about death.3

The focus of my qualitative and explorative research is on the position of Dutch children, aged six to twelve years, during the death ritual. Ethnographic methods were used to collect data. The initial fieldwork comprised of interviews with funeral directors, ritual coaches and families with young children about issues related to death in the family context.

At the time of my fieldwork, in September 2017, I met Astrid Barten and her eighteen-year old daughter Bente Stam.4 In 2009, the Astrid’s husband, and the father of Brechtje, Bente and Wytze, Jan Leen Stam, died unexpectedly while they were on holiday in Austria. Notwithstanding the immense grief, Astrid had no doubts about including their three young children in every element of the death ritual.5 She decided to ask a funeral photographer to participate in the rituals because she considered it important to create material memories for the children. These could help them later on in life to remember what went on at the time of their father’s death.6

Astrid Barten’s actions were very much in line with the conclusions of the research by Søfting et al. They argue that it is important for children to be included in death rituals and to be recognized as grievers alongside adults. Being included meant an improved understanding of what was going on in order to accept the reality of the loss (Søfting et al. 2016). These conclusions affirm the ongoing question of whether young children should attend funerals (Hilpern 2013; Halliwel 2017). Already in 1976, John Schowalter reported on this dilemma: “Although some young children can tolerate funerals well if sensitively supported by their parents, the fact is that such support is more often absent than present. A child no matter how young, who feels secure in attending should usually do so.” (Schowalter 1976, p. 139) My field work results indicate that in the Netherlands children and the death ritual is still a much-debated issue. This raises the question of how ‘death ritual’ is understood. Is it only attending the funeral or should children participate in other rituals, for example, saying goodbye or closing the coffin?

This case study on the Barten family contributes to the discussion in a threefold manner. Firstly, it illustrates how a parent was able to support her children so that they felt confident in participating in the death ritual when their father died, and secondly, it shows and describes hów the children participated and which ritual objects and places were relevant to them. Lastly, the relevance of funeral photographs as mnemonic objects later on in the life of children will be discussed.

2. Research Question and Method

Astrid Barten decided that it was important to document as much as possible for her young children at the time of the death of their father. How were they included in the rituals? What happened and what was their contribution in taking leave of their father? The photographs, put together with a day-to-day description by Astrid and by her mother, the grandmother of the children, in a memorial album could function later as a linking object with that time.

In the nineteenth century, in Western countries, death related photographs were socially and publicly accepted and an acknowledged form of photography (Van der Zee et al. 1978; Ruby 1989, 1995; Linkman 2011). Later generations thought this kind of photography to be inappropriate, and upsetting and as late as 2006, Hilliker acknowledged “the rarity of postmortem photography in the twenty-first century”, although she appreciated the value of “using postmortem photographs as an historical and cultural grieving ritual”. Like Ruby in 1989, she recommended that further research would be appropriate to study the role of death related pictures in bereavement processes (Hilliker 2006, p. 245; Ruby 1989, p. 1).

In this case study I focused on the linking function of photographs, how they served and have become an effective means of memory. Every photo bears the potential of the punctum (Barthes 1981) and “one look, one face, one name can “prick” the casual spectator, trigger a memory […].” (Tandeciarz 2006, p. 139) However not only photographs, but other objects may also act against obliviousness, as described by Hirsch in the context of the memory of the Second World War:

In this case study presentation, based on the funeral photographs of the death ritual of Jan Leen Stam, in combination with the interview with both Astrid Barten and her daughter Bente, I considered the meaning of the photographs of the death ritual, in particular when children lose one of their parents at a young age. A description of the rituals and how the children participated, the places and objects which were created and used during the rituals is given. The photographs, in combination with the story told by Astrid and Bente thus present a visual essay, a “combination of spoken words and visual images” which will, according to Sarah Pink, help me imagine how the events were at the time of death and burial of Jan Leen (Pink 2008, p. 125). Also, the photographs would help me to understand the participation of the children in the death ritual of their father which I was not able to observe personally.Roland Barthes’s much discussed notion of the punctum has inspired us to look at images, objects, and memorabilia inherited from the past […] “points of memory”—points of intersection between past and present, memory and post-memory, personal remembrance and cultural recall. The term “point” is both spatial—such as a point on a map—and temporal—a moment in time—and it thus highlights the intersection of spatiality and temporality in the workings of personal and cultural memory. The sharpness of a point pierces or punctures: like Barthes’s punctum, points of memory puncture through the layer of oblivion, interpellating those who seek to know about the past.(Hirsch 2012, p. 61)

In cultural studies, analysis of the visual has always been integrated. Pink takes a three-fold stand in situating the visual in her research method. The first is that “[…] both researcher and research subjects’ uses of visual methods and visual media are always embedded in social relationships and cultural practices and meanings.” (Pink 2008, p. 131). In this respect, I needed to reflect on the situation when children lose a parent in their childhood, which offers, according to Worden, a very fundamental experience: “The death of a parent is one of the most fundamental losses a child can face.” (Worden 1996, p. 9).

Secondly, Pink argues that “[…] no experience is ever purely visual, and to comprehend ‘visual culture’ we need to understand both what vision itself is, and what its relationship is to other sensory modalities.” (Pink 2008, p. 131). While I did not personally attend the death ritual and was unable to grasp the emotions at the time, I needed the oral story to comprehend the situation when children lose a parent. This is confirmed by the third argument of Pink in upholding the analysis of visual objects:

In compliance with these arguments, I audiotaped the interview and made a full transcript of the recordings which I used for analysis.[…] we are usually actually dealing with audio-visual (for example, film) representations or texts that combine visual and written texts. Thus, the relationship between images and words is always central to our practice as academics.(Pink 2008, p. 131; 2007)

Thus, I was able to reconstruct the social context of the death of Jan Leen Stam and consequently, gain insight into the function and leitmotif of his death ritual.

3. Function and Theme of Jan Leen’s Death Ritual

3.1. Function

Both Astrid and Bente say that the death ritual was very important to them at the time of Jan Leen’s death in 2009. Astrid explained that when he was Austria in a coma and the family understood he was going to die, they initiated the first ritual acts. Together they had all very intensely said goodbye to him. They sat down at his side and spoke to him. Astrid counselled the children to, “Touch him once more, and have a good look at him” and so they did. They also cut a piece of his hair. These were very intimate and private moments, and for that reason they decided not to take pictures at that time. However, both the written diaries of Astrid and her mother on what happened in Austria, and the stories told later on, allow for an embodied recall of the intimate events in the absence of visual material.

During the interview both Astrid and Bente frequently used the term ‘ritual’ when they referred to actions taken around the death of Jan Leen.

The rituals we discussed during the interview belong to a repertoire which Davies refers to as the “mortuary ritual” or death ritual. In his view, this type of ritual should be considered as a form of human response to death: “the human adaptive response to death with ritual language and its ritual practice singled out as its crucial form of response” (Davies 2017, p. 4). At the time, Astrid considered that rituals would help the family in coping with the death of Jan Leen. Davies argues that “having encountered and survived bereavement through funerary rites and associated behavior, human beings are transformed in ways which make them better adapted for their own and for their society’s survival in the world.” (Davies 2017, p. 4). Having spoken extensively with both Astrid and Bente, I would argue that this was the intention of Astrid in organizing, together with the children and closest of kin, a comprehensive death ritual with the objective and focus on the children.

Astrid referred to the mourning process that she realized they all had to go through, a process of adaptation to a life without the physical presence of Jan Leen. Worden defines mourning in terms of the process of adaptation to loss (Worden 1996, p. 11). In order to adapt to the death of a near one he developed what he called “a mourning task model” in which he builds on the concept of Freud’s grief work: “The task model is more consonant with Freud’s concept of “grief work” and implies that the mourner needs to take action and can do something […]” (Worden 2009, p. 38). Astrid indicated that she firmly believed that if the children could take action and participate, just like adults, in the rituals, this would help them in their mourning process.

Worden discerns four tasks of mourning which should be executed during the mourning process. The first task concerns the acceptance of the reality of the loss (Worden 2009, pp. 39–43). As a family they had been there when Jan Leen died and this has helped the children in the recognition of his death and the finality of it. Worden’s second task relates to the charge of experiencing the pain resulting from the loss and to facing the emotions (Worden 2009, pp. 43–46). Bente reflected on her mourning process and said that there has always been room to grieve but also acceptance of how it was, there was nothing they could do to change the situation:” We have been able to let him go, to accept his death but at that time, being a young child, it was logical that we were standing beside him and saying: don’t die, don’t die…”.

The third task concerns the process of adjusting to an environment in which the deceased is (physically) missing (Worden 2009, pp. 46–49). The fourth task is the process of emotionally relocating the deceased within one’s life and finding ways to memorialize the person and consequently to move on with life (Worden 2009, pp. 50–53).

Worden initially developed his model for adults. Other researchers in bereavement studies have developed models with specific mourning tasks for children (Baker and Sedney 1992; Cook and Oltjenbruns 1998). Worden, accordingly commented as follows:

According to Worden, mourning tasks apply to children, but they should be understood in terms of the cognitive, emotional and social development of the child (Worden 2009, p. 235). For example, a child who has not developed the cognitive abstractions of irreversibility and finality will have difficulty with the first task of accepting and realizing that death is final and irreversible.Researchers who apply my “tasks of mourning” concept to children have suggested various numbers of mourning tasks […] Although their conceptualizations are interesting, I do not believe we need to include additional tasks. The issues concerning bereaved children can be subsumed under the four tasks of mourning described in my earlier work, but I have modified them here to take into account the age and the developmental level of the child.(Worden 1996, p. 12; 2009, pp. 230–36)

Worden specifically mentions family rituals as “important mediators influencing the course and outcome of bereavement.” (Worden 1996, p. 21) They can help children in a three-fold manner: as a means of acknowledging the death, as a way to honor the life of the deceased and as a means of comfort and support. However, Worden concludes that children should be given a choice as to whether they want to attend, and for example, whether they want to view the body. In all cases they should be clearly informed of what they are about to experience (Worden 1996, p. 21).

Astrid was very much in charge of organizing the rituals. She said that she knew what and how she wanted it. She thought it was important that the children should decide for themselves whether they wanted to participate: “The funny thing was that they wanted to participate in everything that took place. They were not one moment scared of death.” She remembers one particular time when in fact the children took the lead: “At the moment we were about to close the coffin, you (Bente) were the first one to give dad a kiss to say goodbye. The others followed.”

3.2. Theme

Astrid explained that in Austria, when Jan Leen was in a coma, she had told him that it was okay to go. It had been the ‘ultimate letting go’. This letting go of his physical presence became a recurring element in his death ritual. Although the family believes him to be somewhere else, he still remains a part of their life, and they treasure him within their hearts. They refer to his transfer from being a physical presence to a presence elsewhere. This transfer turned into the leitmotif of his death ritual and may be explained by applying the framework of so called ‘rites de passage’ (rites of passage). In 1908, Arnold van Gennep described the way people passed from one social status to another (Van Gennep 1960, pp. 10–11, 21). He recognized three stages in this process of transfer: separation, transition and reincorporation. Using the Latin word limen (threshold) to describe these phases, he spoke of pre–liminal (separation), liminal (transition), and post–liminal (reincorporation) phases in rites of passage.

These phases can be applied both to the transfer of the deceased but also to the position of the family left behind who also have to adapt to the transfer from physical presence to another presence.

Herz, in his seminal essay on death and the collective representation of death, presented just before Van Gennep, discussed the death ritual in a similar way too (Hertz 1960). In a commentary on his work, Davies reflects on the change of status emphasized by Hertz:

Turner elaborates on the different phases identified by Van Gennep. The first phase of separation comprises “symbolic behavior signifying the detachment”. During the dominant, second, liminal period, the characteristics of the ritual subjects, which are the “passengers through this phase’”, both the deceased and bereaved are ambiguous and in the third phase, the phase of reincorporation, the passage has been completed and the ritual subjects should be in a sort of stable state, while the deceased has made the transfer to the other world (Turner 1969, pp. 94–95).Writing just before Van Gennep published his now familiar thesis of rites of passage in 1909, Hertz speaks of funerary rites in a very similar way. These rites resemble initiation in that the dead, like the youth who is withdrawn from the society of women and children to be integrated into that of adult males, also change status. Poignantly, then, death resembles birth in transferring an individual from one domain to another.(Davies 2000, p. 99)

Turner emphasized the liminal period and explored the dynamics of what happens to people when thrown together in periods of stress and the change of identity caused by the death of a near one. He developed the concept of communitas to describe this shared fellow-feeling, a feeling of connectedness (Turner 1969, p. 96), and this was interpreted by Davies as “[…] a sense of unity and empathy between people undergoing ritual events together” (Davies 2017, pp. 26–27, 94).

Although discerning the exact phases in the death ritual of Jan Leen is arbitrary, applying the discussed concepts in a case where children participate may be useful in interpreting the process and accompanying rituals. Bente commented that you might think that when you are nine years old, you will remember everything but when she looks back on these days it seems like everything happened in just two days: one day they got to know in Austria that Jan Leen was braindead and to her it seemed as if the funeral was held the day after. In her view they really were in a sort of ‘liminal’ period where there was no comprehension of time.

In the next paragraph I will discuss six photographs of Jan Leen Stam’s death ritual. These photographs were chosen in consultation with both Astrid, Bente and myself. The funeral photographer advised on the quality of the pictures. In particular, these six photographs were chosen because they create a comprehensive visual narrative and materialize the events that took place at the time. The photographs have a two-fold function: the first is to illustrate how the Stam children participated in the death ritual of their father and secondly, these photographs function as mnemonic objects to memorialize the events at the time of the death of their father.

The first photograph (Photograph 1) was taken after Jan Leen had returned home from Austria. At that time, they created a special place for him in order to welcome him back home.7 Astrid said: “All together we organized the room where he would stay. I put up photographs of Jan Leen and the children, there were flowers”. Other symbolic acts at this time included the objects they placed in his coffin for him on his way to the other world.

Astrid asked the children: “What would you like to put in the coffin, when you think of dad, what comes up, which things would you like to place with him?”.

Bente wrote a letter and put it in the coffin. Her older sister Brechtje made a drawing about how she thought it would be up there in his future home in the clouds. There was also discussion and they put things in the coffin which would remove again later, for example, a pickax that was his and symbolized him as a mining engineer. Astrid thought the children were better off keeping the ax as an object of memory, and instead they placed a stone in the coffin. They also took care that he had his glasses with him as they very much belonged to him as the person he was.

In the photograph we see the children painting the coffin. They left their hand prints on top as a personal sign of bonding with their father.

The objects they put into the coffin functioned as so called “transitional objects”. Winnicott was the first to describe this term ‘as an object that becomes crucially important to the child in the process of separation from the mother (Winnicott [1971] 1997, pp. 1–34). These objects seem to be invested with a certain magical quality and offer comfort and security to the child (Gibson 2004, p. 288). In this case there were two type of transitional objects: first, the objects belonging to Jan Leen himself that they thought characterized him and that had to go with him, like his glasses, and second, the objects the children especially created for him as memory objects. These objects connect the world their father was leaving with the world he was about to enter and may be helpful in the transition process of separation and acceptance of the fact that the parent has actually died (Winnicott [1971] 1997; Worden 1996, 2009). Margaret Gibson argues that, “In grieving, as in childhood, transitional objects are both a means of holding on and letting go” (Gibson 2004, p. 288).

These two aspects of a transitional object are illustrated by the pick ax which they first decided to ‘let go’ with him but consequently decided to ‘hold on’ to.

According to Turner, these are all ritualistic acts of “symbolic behavior signifying the detachment” from Jan Leen which is part of the phase of separation from his physical presence (Turner 1969, pp. 94–95).

The male family members, including six-year-old Wytze, closed the coffin (Photograph 2). Astrid remembered: “This was a very emotional moment because I knew “I am never going to see you again”, the funny thing is that I sort of thought it was okay that the body would leave, but there was also the understanding that this was really the end.” She did not think that the children had a proper understanding of the finality of that moment. Bente confirms: “When I look back, I now realize much more than I did at the time that that moment was really the last time that you actually see someone. I think it is a very intense moment. But at the time I was just watching, fascinated how they were putting the screws on.” Thus, the photograph functions as a reminder, a mnemonic object, of the finality of the death of her father.

Astrid decided at the time that the actual burial should be focused on the family, a small intimate group of close family members, so that the children could be with her, without having to worry about other people. As Van Gennep points out, “[…] during mourning, the living mourners and the deceased constitute a special group, situated between the world of the living and the world of the dead” (Van Gennep 1960, p. 147).

They acted together as a communitas of dear ones, the next of kin of Jan Leen, to feel a sense of unity and empathy in sharing their emotions and grief (Turner 1969, p. 96; Davies 2017, pp. 26, 94). Astrid explained: “There was so much sorrow, I strongly felt the need to do the burial with the children without a leaking of energy to other people who mattered less at that moment.” Hence, she held the actual burial of Jan Leen separately, with a public service held in his honor a couple of weeks later.

Astrid decided that at all times during the burial ritual, they would be together in the communitas of the family. That is why she decided to hire a coach used especially for funeral processions: “I did not want him to be somewhere else than we were.” All together in the coach, they made a good-bye tour through their village including the important places in the life of Jan Leen, for instance, they passed the house where he was born and raised.

The day of the burial, they all dressed in white. Astrid explains: “Jan Leen was very much a bon vivant, he lived so to say, as a “light life”. During his life, he did not spend one minute on the wrong energy, and that went hand in hand with a sort of lightness. I did not hesitate for a second; everything would be in white.”

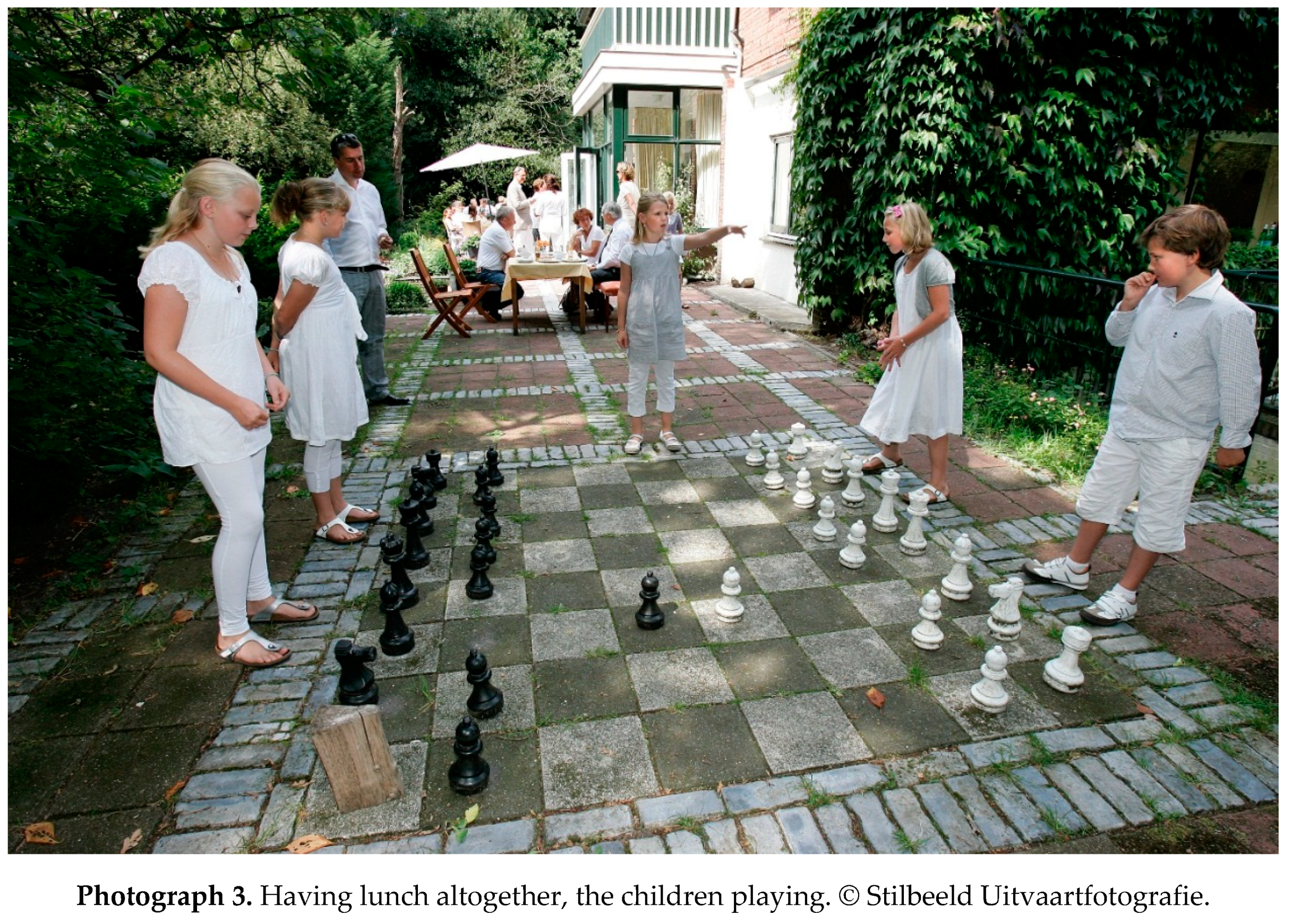

Before going to the graveyard, Astrid wanted to have lunch with the family but Jan Leen had to be there as well. It was his day. The funeral director found a restaurant where they could take him in his coffin with them. They had lunch as one family, and there was time for the children to play (Photograph 3).

The design, places and enactment of the burial rituals appear to be out of the ordinary. In this respect, they seem to refer to the liminal zone in which they were positioned at that time. In the words of Turner, “Liminal entities are neither here or there; they are betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom and convention, and ceremonial” (Turner 1969, p. 95). That is why, maybe not unexpectedly, we observe children playing as if they are having a good time at the day of their father’s burial, “betwixt and between”. Here, the rituals were designed and performed taking into account the young age of the children. In Bente’s opinion they were celebrating his life. That is how they experienced the ritual: “We have been celebrating, and we have not, well…of course we were sad, but we did not despair so to say.” There are no tears, not in any photograph. However, Astrid said: “Sometimes the photographs still frighten me because we all look so very much fatigued.”

Astrid explained that she and the children chose the actual place of burial (Photograph 4): “What would be a nice place for dad?” They chose a place which would be easy for the children to visit later on and so that they would not have to cross the whole graveyard on the way to their dad.

A couple of months before his death, Astrid had discussed with her husband whether he wanted to be cremated or buried. He had to have surgery and Astrid wanted to know, just in case. He preferred to be cremated, but Astrid felt that at such a young age it would be important for their children to have a place to go to: “When you have young children, I think that burial enables rituals, to experience their father, also after his death.” Jan Leen had agreed.

Maddrell argues that maintaining bonds with the deceased may be experienced in different forms, for example, through ritual but these bonds can also be sustained through material objects such as graves, memorials or photographs (Maddrell 2013, p. 508). Hallam and Hockey argue that a “material focus” facilitates relations between the living and the dead. As they state: “Past presence and present absence are condensed into a spatially located object”, like the grave or photographs (Hallam and Hockey 2001, p. 85).

At the moment of burial, they lit candles and put rose petals on the coffin. They sent up balloons as a symbolic act of letting him go.

According to Astrid, the actual burial was essentially about seeing Jan Leen off to his last resting place. In terms of Van Gennep and Turner, the phases of separation and transition had been achieved by this time. There were no speeches at the graveyard. Jan Leen had a large social network and Astrid also felt the need to show the children who their father was. Therefore, she asked all his friends, colleagues and family to document his life on behalf of his children. At the public service they celebrated his life and the children fully participated by lighting candles but also by presenting (Photograph 5). Bente recited a poem written by herself, Brechtje recited an English poem and Wytze read his self-written text, which was also in the death notice. The service turned out to be extremely long; around 2.5 h. Astrid had bought pencils and coloring books and candy for the children who were partly listening and partly playing, but they were present at all times.

Grimes comments on the elements of a good funeral: “If deaths can be good or bad, so can funerals. A good funeral is one that celebrates life, comforts the bereaved, and facilitates working through grief” (Grimes 2000, p. 230). However, from Astrid’s perspective, the celebration of Jan Leen’s life could not be done at his burial. That moment was in fact the closing of the period in which they were separating themselves from his physical presence, a very sorrowful time. Celebration of his life would be the start of incorporation into the new world without the physical presence of Jan Leen and the ending of the liminal period defined by Van Gennep and Turner (Van Gennep 1960; Turner 1969). Altogether, the rituals comprised a ‘good funeral’ in their eyes (Grimes 2000, p. 230).

Jan Leen’s grave is an important place to the family. When there are memorable moments, such as passing exams, the family visit his grave and tell him. In the beginning, they would go every week on their way to school, a genuine ritual, but now they go less. Yearly, on his birthday in January, the family gather around his grave at 5 p.m (Photograph 6). Sparklers are lit, and there is room for informal speeches. There may even be cheerful moments: one time a little nephew said that he wanted to sing a Dutch birthday song, Lang zal hij leven (Long shall he live) for his uncle. They thought that this was probably not a very good idea!

Astrid said: “On the day of his death, the children think it is important to do the same thing every year.” They visit the grave and afterwards they all go and have Chinese food. This year, it is going to be different because Brechtje, the oldest daughter, will be abroad studying in Vienna.

Davies reflects on the words of Herz and how the mourning process takes some time: “Still, he speaks of the “painful psychological process” of separating the dead from the consciousness of the living. Ties with the dead are not “severed in one day”, memories and images continue through a series of “internal partings”” (Hertz 1960, p. 81; Davies 2000, pp. 99–100).

The rituals that the family performs on relevant days also relate to the mourning tasks described by Worden and which are concerned with the process of emotionally relocating the deceased, in this case Jan Leen as father of the children, within one’s life and finding ways to memorialize the person and consequently, to move on with life (Worden 1996, pp. 10–17). Discussion on the issue of how to maintain a relationship with the deceased without being too troubled in daily life, is topical in bereavement studies. In 2018, more than twenty years after the term “continuing bonds” was introduced, Klass and Steffen conclude that retaining bonds with the deceased is an accepted option in bereavement processes (Klass and Steffen 2018). The Stam children cherish the bond they still have with their father. At the time of the interview Bente was wearing one of his old fleece jackets.

Up until the 1990s, based on the philosophy and ideas of Freud, the “breaking bonds” approach was dominant, that is, the bereaved should be freed from all ties with the deceased in order to create energy for new relationships (Freud 1917). Now, in 2018 the continuing bonds paradigm is supported by a reasonable amount of research and described practices (Stroebe et al. 1992; Shuchter and Zisook 1993; Klass et al. 1996; Goss and Klass 2005). The bereaved may “retain the deceased” (Walter 1996, p. 23) and the relationship does not have to be severed but may be transformed and achieve a different character (Shuchter and Zisook 1993, p. 34). As Astrid says: “Jan Leen is always with us. There is not a day when his name is not mentioned. The children have always had the possibility to reach out to their father and to continue in bonding with him.” (Silverman and Worden 1992a, 1992b; Silverman and Nickman 1996; Worden 1996).

Up until today, the leading research in this area is the Child Bereavement Study, which investigated the impact of a parent’s death on children from ages six to seventeen (Silverman and Worden 1992a, 1993; Silverman and Nickman 1996; Worden 1996) Interestingly, in this study the children themselves were interviewed and invited to express their opinion. Analysis of the data focused on how children talked about the deceased near one. It appeared that relationships with deceased parents were maintained rather than broken. The children kept all kinds of objects belonging to their parents and created a continuing link. In time, when there was less grief and when the children grew older, the relationship appeared to change and there was less need for such objects. A continuing relationship appeared to be part of a normal bereavement process. At that time, such a conclusion was contrary to what the researchers called traditional bereavement theory, that is, the breaking bonds paradigm. It was observed that the construction of a continuing bond with the dead parent provided comfort to the children and seemed to facilitate coping with their grief (Silverman and Nickman 1996, p. 73). The advice was that children should learn to remember and to find ways to maintain a way of reaching out to the deceased. This way should be coherent with the child’s cognitive development, how death is understood, and the dynamics of the family in order to allow the child to continue living despite the loss of the parent (Nagy 1948; Silverman and Worden 1992a; Worden 1996; Silverman 2000).

One of Astrid’s mantras when Jan Leen died was “to get back to a normal life as soon as possible and do the things that the children used to do”, like going out and having dinner at the beach. She also realized this would be very emotional because it would be the four of them instead of five, and their life had been completely turned upside down. However, at the time of the interview she reflected that for them the mourning process seems to have finished in the sense that they have all regained “an interest in life, feel more hopeful, experience gratification again, and adapt to new roles. (Worden 2009, p. 77). Worden describes the completion of the mourning process:

According to Astrid, when a parent dies at a young age you should see it as a life that was accomplished, you should not live on with the thought of what could have been but instead try to be thankful for what has been. Sometimes this is difficult, particularly for her youngest son, Wytze. Wytze was only six years old when his father died. He does not have many of memories of him. Astrid tell him he should try to remember the feeling of loving him and they have photographs and movies which they watch.One benchmark of mourning moving to completion is when a person is able to think of the deceased without pain. There is always a sense of sadness when you think of someone you have loved and lost, but it is a different kind of sadness—it lacks the wrenching quality it previously had. One can think of the deceased without physical manifestations such as intense crying or feeling tightness in the chest. Also, mourning is finished when a person can reinvest his or her emotions into life and in the living.(Worden 2009, pp. 76–77)

3.3. Function and Meaning of the Photographs

During the interview Astrid Barten, her daughter Bente and I looked at the photographs of the death ritual of Jan Leen. Bente had not seen them for a long time. As her mother recalled the time of her father’s death, the photographs brought back lost memories and not only provided a bridge between past and present, but also (re)constructed this past, particularly for Bente. In this way, the photographs seemed to construct a bond between emotional and important moments at a time when she was young, and the present. In the context of this article, I would argue that not only objects belonging to the deceased parents, but also objects, like photographs showing relevant moments of the death ritual may serve as transitional or in the words of Gibson, “melancholy objects”, recalling the memory of early grief and the grief of time passing” (Gibson 2004, p. 289). These may be helpful in the construction of a new relationship with the deceased parent. In her book, Objects of the Dead, Gibson discusses photographs in the context of transitional objects: “As children and parents look at photographs together, a bridge between the past and the present is created, through stories, conversations, questions and answers” (Gibson 2008, pp. 88–89).

A memorial book was made with written stories about Jan Leen’s life and the death ritual photographs were put together in an album with descriptions of what happened at the time of his death.

However, the children do not seem to need these material objects at this time of their life. Astrid explained, “I have made a wonderful memorial photo album, the children have never looked at it, but that’s okay, it is there, so if they need it, it is there, but apparently they never felt they needed it. They all have a book in their own room and they can take it with them when they are going to live on their own.”

In line with Sontag and Gibson, the photographs may be considered as melancholy objects as they create” the image of time, and the time of the image” (Gibson 2004, p. 286; Sontag 1977). At this time of their life there is no need to reflect on the time of the death of their father. They have found other ways, like visiting his grave and daily talking about him, to create a presence of what could be an absence because of their young age at the time he died (Maddrell 2013).

Although the photographs do not seem to have an apparent function for them at this moment, they have potential agency (Meyer and Woodthorpe 2008): intrinsically, they have the power to recall emotional and difficult times in the past and they are right at hand, in the children’s rooms whenever they need them.

They construct a visual narrative that displays traces of the family life through significant events (Gibson 2004). In general, funerary photography may have this function (Ruby 1989, 1995; Hilliker 2006; Linkman 2011). For example, the value of having photographs of stillborn babies has been expressed by bereaved parents and family (Meredith 2000). For children who lose a parent at a young age, there might also be value in these photographs because they enable the children to construct the history of the time of the death of their parent.

The photographs showed how the Stam children consciously participated in the death ritual of their father and how they were recognized as grievers alongside adults, in particular, by their mother. The importance of taking part in the ritual is shown by the study of Søfting et al. Their mother’s open attitude and focus on involving them the whole time, contributed to their accepting and coping with the death of their father (Søfting et al. 2016). This case study presentation helps to answer the question of whether young children should attend funerals in the affirmative (Hilpern 2013; Halliwel 2017).

4. Conclusions

The sorrowful words of six-year-old Wytze also carry a powerful statement: we will manage daddy….Dear daddy,Make a nice tiny house on your little cloud. Go to your new life. We will pull through, daddy.O daddy, daddy, we will miss you for ever and always.You are the sweetest daddy of the whole world.Wytze8

And they did.

Jan Leen Stam died when the children were still at a young age and Astrid Barten will always regret that the children lost their father: “I regret so very much that the children lost a wonderful father. It is horrible that he has not been able to educate them with his esteemed spirit, with his “being”. But I know, as a family we went through a lot of good things together. I am very proud how the children went on with their lives”.

The funeral photographs showed how they participated as a family in the death ritual of their father. Presently, the funeral photographs of Jan Leen Stam do not seem to have a specific function. However, these photographs may become effective media for remembering and learning about a decisive moment in their life whenever the children feel the need to do so.

The conclusion of this case study presentation is that funeral photographs of death rituals can function as mnemonic objects when children lose a parent during childhood. In this respect, they can be seen as meaningful objects in funeral culture, particularly when young children are involved.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the Stam–Barten family and Dasha Elfring (Stilbeeld Uitvaartfotografie) for their kind cooperation in this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The author declares that all privacy and copyrights issues have been cleared.

References

- Ariès, Philippe. 1994. Western Attitudes toward Death: From the Middle Ages to the Present. Translated by Patricia M. Ranum. London: Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd. First published 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, John E., and Mary A. Sedney. 1992. Psychological tasks for bereaved children. Theory and review. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 62: 105–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. France: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Inc., Available online: https://monoskop.org/images/c/c5/Barthes_Roland_Camera_Lucida_Reflections_on_Photography.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2018).

- Cook, Alicia S., and Kevin A. Oltjenbruns. 1998. Dying and Grieving: Lifespan and Family Perspectives. Forth Worth: Harcourt & Brace. [Google Scholar]

- Dakin, Glenn. 2017. Coco The Essential Guide. New York: DK Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Douglas. 2000. Robert Hertz: the social triumph over death. Mortality 5: 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Douglas. 2017. Death, Ritual and Belief. The Rhetoric of Funerary Rites, 3rd ed. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Disney PIXAR. 2017. The Art of Coco. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, Sigmund. 1917. Trauer und Melancholie [Grief and melancholy]. Internationale Zeitschrift für Artztliche Psychoanalyse 4: 288–301. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Margaret. 2004. Melancholy objects. Mortality 9: 285–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Margaret. 2008. Objects of the Dead. Mourning and Memory in Everyday Life. Victoria: Melbourne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goss, Robert E., and Dennis Klass. 2005. Dead but Not Lost: Grief Narratives in Religious Traditions. Oxford: Alta Mira. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, Ronald L. 2000. Deeply into the Bone. Re-Inventing Rites of Passage. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hallam, Elizabeth, and Jenny Hockey. 2001. Death, Memory and Material Culture. Oxford: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Halliwel, Rachel. 2017. Is It OK to Take a Young Child to a Funeral? The Telegraph. October 7. Available online: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/family/ok-take-young-child-funeral/ (accessed on 28 November 2017).

- Hertz, Robert. 1960. Death and the Right Hand. Translated by Rodney, and Claudia Needham. London: Cohen and West. [Google Scholar]

- Hilliker, Laurel. 2006. Letting go while holding on: Postmortem photography as an aid in the grieving process. Illness, Crisis & Loss 14: 245–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hilpern, Kate. 2013. Should Young Children Go to Funerals? The Guardian. July 12. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2013/jul/12/should-young-children-go-to-funerals (accessed on 29 November 2017).

- Hirsch, Marianne. 2012. The Generation of Postmemory. Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Klass, Dennis, and Edith M. Steffen, eds. 2018. Continuing Bonds in Bereavement: New Directions for Research and Practice. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Klass, Dennis, Phyllis Silverman, and Steven L. Nickman, eds. 1996. Continuing Bonds: New Understandings of Grief. London: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Linkman, Audrey. 2011. Photography and Death. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Maddrell, Avril. 2013. Living with the deceased: absence, presence and absence-presence. Cultural Geographies 20: 501–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, Rachel. 2000. The photography of neonatal bereavement at Wythenshawe Hospital. Journal of Audiovisual Media in Medicine 23: 161–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, Morgan, and Kate Woodthorpe. 2008. The material presence of absence: A dialogue between museums and cemeteries. Sociological Research Online 13: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Maria. 1948. The child’s theories concerning death. The Pedagogical Seminary and Journal of Genetic Psychology 73: 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, Sarah. 2007. Doing Visual Ethnography. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Pink, Sarah. 2008. Analysing visual experience. In Research Methods for Cultural Studies. Edited by Michael Pickering. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 125–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ruby, Jay. 1989. Portraying the dead. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying 19: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, Jay. 1995. Secure the Shadow. Death and Photography in America. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schowalter, John E. 1976. How do children and funerals mix? The Journal of Pediatrics 89: 139–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuchter, Stephen R., and Sidney Zisook. 1993. The course of normal grief. In Handbook of Bereavement. Edited by Margaret Stroebe, Wolfgang Stroebe and Robert O. Hansson. New York: Cambridge Univesrity Press, pp. 22–43. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, Phyllis R. 2000. Never too Young to Know. Death in Children’s Lives. New York: Oxford Univesrity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, Phyllis R., and Stephen L. Nickman. 1996. Children’s construction of their dead parents. In Continuing Bonds. New Understandings of Grief. Edited by Dennis Klass, Phyllis R. Silverman and Steven L. Nickman. New York: Routledge, pp. 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, Phyllis R., and William Worden. 1992a. Children’s reactions to the death of a parent in the early months after the death. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 62: 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, Phyllis R., and William Worden. 1992b. Children’s understanding of funeral ritual. Omega: Journal od Death and Dying 25: 319–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, Phyllis R., and William Worden. 1993. Children’s reactions to the death of a parent. In Handbook of Bereavement. Edited by Margaret Stroebe, Wolfgang Stroebe and Robert O. Hansson. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 300–16. [Google Scholar]

- Søfting, Gunn Helen, Atle Dyregrov, and Jari Dyregrov. 2016. Because I’m also part of the family. Children’s participation in rituals after the death of a parent: A qualitative study from the children’s perspective. Omega-Journal of Death and Dying 73: 141–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontag, Susan. 1977. On Photography. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe, Margaret, Mary Gergen, Kenneth J. Gergen, and Wolfgang Stroebe. 1992. Broken hearts or broken bonds. Love and death in historical perspective. American Psychologist 47: 1205–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandeciarz, Silvia R. 2006. Mnemonic hauntings: Photography as art of the missing. Social Justice 33: 135–52. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Victor. 1969. The Ritual Process. Structure and Anti-Structure. New Brunswick: Aldine Transactions. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Zee, James, Owen Dodson, and Camille Billops. 1978. The Harlem Book of the Dead. New York: Morgan & Morgan. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gennep, Arnold. 1960. The Rites of Passage. Translated by Monika B. Vizedom, and Gabrielle L. Caffee. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, Tony. 1996. A new model of grief: bereavement and biography. Mortality 1: 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnicott, David. 1997. Playing and Reality. Kent: Tavistock/Routledge. First published 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Worden, William. 1996. Children and Grief. When a Parent Dies. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Worden, William. 2009. Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy: A Handbook for the Mental Health Practitioner, 4th ed. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Zerubavel, Eviatar. 2003. Time Maps. Collective Memory and the Social Shape of the Past. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | https://www.disneyclips.com/lyrics/coco-remember-me.html; Lyrics from ‘Coco’, written by Kristen Anderson-Lopez and Robert Lopez, performed by Miguel, featuring Natalia Lafourcade. |

| 2 | For an impression of this glossy see: http://www.later-alsikdoodben.nl/doelgroep/ (consulted on 18 June 2018). |

| 3 | http://www.totzover.nl/educatie/ (accessed on 10 June 2018). |

| 4 | This semi-structured interview took place on 1 September 2017. The interview was recorded and transcribed for analysis. Informed consent was obtained for publication of the data. |

| 5 | Eldest daughter Brechtje Stam was twelve years old, Bente nine years old and Wytze six years old at the time of the death of their father. |

| 6 | The photographs were made by Dasha Elfring, a Dutch funeral photographer with her own company Stilbeeld Uitvaartfotografie: http://www.stilbeeld.nl/index.html. Permission was obtained to publish the photographs. |

| 7 | Out of respect to Jan Leen, and because, obviously, he was not able to give his consent, Astrid decided not to include any photographs of Jan Leen himself in the visual essay. |

| 8 | Text written by Wytze Stam to appear on the death announcement of his father. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).