Abstract

The procession known as “Lord of Miracles” is a massive religious phenomenon that takes place in various cities around the world in October. The purpose of this study is to describe and analyze certain elements of the procession, which champion not only the idea of unity (religious, cultural, ethnical, and national), but also the sociocultural differences. With this in mind, we conducted ethnographical research focused on the processions that took place in Barcelona, Spain, in 2016 and 2017. Along with a number of practices and talks intended to activate and strengthen the image of religious unity (Brothers in Christ) and national unity (Brothers of Peru), there are certain dynamics that point to differences, which call that unity into question. Specifically, we focused our study on two seasons of the procession: the scissors dance and the Marian, both dances for the Lord. However, the type of interaction that happens with each of them shows inner differences, which the members establish with the image of the Cristo moreno. These differences are expressed in the special-temporal location of certain stations—which represent subordinate sociocultural manifestations—and in the type of interaction, which the members establish with the image of the Cristo moreno.

1. Introduction

The procession of the Lord of Miracles is a widely popular religious festival that is currently celebrated in countless cities around the world during October. In Barcelona, Spain, hundreds of migrants—mostly from Peru but also from other Latin American countries—gather to participate in a spectacular procession dedicated to the Cristo moreno, or Colored Christ, as they call him. It is presently the most important and well-attended urban celebration for Peruvians and their descendants living in Barcelona.

Traditionally, this type of religious festival has been seen as a mere extension of the cults of origin that echo the official Catholic canon, and their internal homogeneity is overestimated (Altamirano 2000; Ruíz Baia 1999; Paerregaard 2008). From our recent ethnographic experiences in the city of Barcelona (October 2016 and October 2017), we were able to discern that the procession of the Lord of Miracles is a complex ritual event in which a series of elements (cultural, religious, ethnic, and national) are blended together and whose logic merits analysis. In the context of our study, we noticed that both the internal similarities and differences of the community are manifested through distinct symbolic and ritual forms.

Specifically, we found that there are various practices, speeches, and symbols in the celebration that refer to the unity of the celebrant group and their identification as Peruvian brothers, devotees of the Lord of Miracles, or both. These identifications may be intermingled and enhanced through rituals and are relatively well accepted by the majority of celebrants. On the other hand, and despite the power of the twofold reference to their identity-based unity, a series of coexisting practices, performances, and symbols call into question, or at least cause tension in, this unity, which is proclaimed explicitly and implicitly throughout the celebration. Although they appear to be secondary or marginal manifestations, their incorporation into the very structure of the celebration attests to their importance. Our objective was to describe and analyze the presence of both manifestations and the relationships they weave during the procession, thus revealing part of this complex cultural phenomenon.

Our working hypothesis was that, in a migratory context like the one in Barcelona, over the course of the procession of the Lord of Miracles, there would be an attempt to incorporate various sociocultural elements and groups reflecting the diversity present in Peru in order to achieve greater sociocultural integration through this religious expression (in a country where Catholicism continues to play a significant role in both the public and private spheres). However, we thought this attempt would not only demonstrate the dominant position that religious and national unity occupy but also give rise to cultural expressions that escape notice or produce tension in the city. Thus, the procession appears to be a staged ritual that is especially relevant in the urban space where both religious and national references to identity may be recreated and represented in a particular way.

As authors who have been published on the subject of the Peruvian diaspora noted (Banchero 1972; Paerregaard 2002, 2005, 2008; Rostworowski 1992; Ruíz Baia 1999 stand out), it is easy to detect a social and cultural change in iconographic meaning, to which other aspects might be added, including what Werbner (2002, p. 119) calls “chaordic” transnationalism, which come to form networks of transnational links that are based on three paradoxes: of the one in many; of the place of no place; and of global parochialism. The latest, deals with ties that move from national identity to particular devotions, in both directions, driven by “ideascapes or religioscapes” (McAlister 1998; cited in Garbin 2012), whether in the form of regional cults, messianic movements, or other belief systems. Our article continues along this research strand.

Additionally, we adopt a perspective that focuses on the analysis of ritual as a phenomenon “in itself” (Houseman 2012) and with its own logic (Houseman and Severi 2009).

2. The Celebration: From Colonial Pachacamilla to the Barcelona of the Present

To examine the history of the procession of the Lord of Miracles, we must go back to 1650, when the Viceroyalty of Peru was ruled by Viceroy García Sarmiento Sotomayor and the Archbishopric of Lima was held by Pedro de Villagomez. That year, a group of people of Angolan origin formed a guild or brotherhood and established a meeting place in the outskirts of Lima, in the Pachacamilla area. The story, tinged with legend, goes that an Angolan slave surnamed Dalcón made a rustic painting of the image of a crucified Christ on one of the walls of the premises. In 1655, a major earthquake shook the city of Lima, destroying much of the city. All of the adobe walls of the guild’s premises collapsed except the one where the image of Christ was depicted. The legend recounts that it remained completely intact, without even the slightest crack. Since then, the image of this Christ has been an object of devotion for people of African origin in the area and its environs (Banchero 1995). A few years after the first Mass was celebrated, on 20 October 1687, a violent earthquake again struck the city of Lima. The earthquake brought down the hermitage built in honor of the Lord of Miracles, but the wall where His image again miraculously remained standing. At that time, it was decided to make a copy of the image as an oil painting, in order to preserve it, and to take it out in procession through the streets of Pachacamilla as a means of protection against the tremors and earthquakes that constantly afflict the country. This power would be linked to the cult, of pre-Hispanic origin, which worshipped the god Pachacámac in this area (Rostworowski 1992). From then on, the cult became official among the residents of Lima and he began to be referred to popularly as the Lord of Miracles (Banchero 1995).

The fame of the Lord of Miracles, also called the Christ of Pachacamilla or Cristo moreno, has continued to grow and spread around the world. During the last few decades, his religious cult has benefited from the large number of Peruvian migrants that have dispersed around the world (Merino 2002), which has transformed the procession into an expression of religiosity around the world. This is the case in Barcelona, a city that witnessed the birth of a new chapter of the Brotherhood of the Lord of Miracles in July 1992. That year, the Peruvians Rosa Uchuya and Rosa Cruzatt, faithful devotees of the Cristo moreno, decided to found the brotherhood and request a mass in his honor in the cathedral of Barcelona. At the same time, they began to take steps to bring an oil painting with the image of the Lord of Miracles from Peru for worship. At that time, the number of Peruvians in Barcelona was quite small, and the events in which members of this cult participated were held in common public places frequented by Peruvians, such as restaurants and public squares. After 25 years, the Peruvian community in Barcelona has grown significantly, as has its diversity in social class and cultural capital, and the number of believers who participate in the brotherhood to worship the Lord of Miracles has also increased and become more diverse.

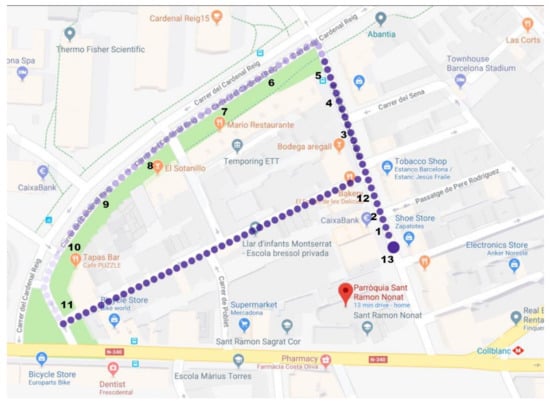

In its beginnings, 25 years ago, the Lord of the Miracles procession (initiated by two Peruvian female migrants) passed through the Cathedral of Barcelona, in Spain, following a brief tour that included very tight and small streets in the center of the city and a reduced number of parishioners who gathered, and did not take into account the rules of city hall. Afterwards, the location and attendance range for the procession was changed. In 2017, celebration of silver weddings, the procession of the Lord of the Miracles passes through one of the peripheral neighborhoods of Barcelona. The route lasts for seven hours, occupies an avenue, and blocks traffic on two streets and 13 stations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Stations, groups, and cultural events in the 2017 procession.

As can be seen on the map (see Route map 2017), the route of procession, for the most part, currently goes along Sant Ramon Nonat Avenue, which owes its name to the parish church. We can consider the following to be of central importance to the Lord of Miracles procession: the start and the finish of procession route (Maps 1 and 13), the station General consulate of Perú where the consultant speaks a few words to the procession celebrants (Map 2), stations where it is presented and admired with great enthusiasm and passion (Maps 1–5 and 11–13), the national dance of Perú called La Marinera (Maps 4, 7, and 12), and the places where they sing the national hymn (Maps 1 and 13). All of these stations are placed along the avenue.

Part of the data helps us visualize the contrast between the two neighborhoods that are literally “cheek to cheek” on Sant Ramon Nonat Avenue. On one side, we have the one we have analyzed: the Les Corts district, which is fourth in size among the districts in Barcelona, has an area of 6.08 km, is located in the eastern part of the city, and currently has 81,570 citizens, from which 10.9% are foreign, forming a neighborhood comprised of a mainly authentic population that is supported by young people who form part of the middle class and whose principal economic activities take place in the third sector, even though the area includes a large number of financial and office buildings and a football stadium in the center. On the other side, Collblanc is a neighborhood of Hospitalet de Llobregat, with an area of 0.51 km, has 24,247 residents as of 31 December 2017, 27.66% of whom were foreign born (2016), is known as a working class neighborhood, and has its own procession of the Lord of Miracles that takes place one week later.

In the 2016 and 2017 celebrations of the procession, we noted (see Table 1 and Table 2) that, in the section that runs along Sant Ramon Nonat Avenue, there were five stops, which correspond to the first five stations of the procession. Toward the end of the route, there were two stops corresponding to Stations 12 and 13. Another stop was made where the blessing of children and babies before the Lord of Miracles is performed and before the subsequent dance of the image led by the image bearers in front of the parish church, just before the image was taken inside. Table 1 and Table 2 show the stations that the procession of the Lord of Miracles passed through in 2016 and 2107, the organizations that were in charge of each of them, and the music and dance that they performed during the passing of the image of the Lord of Miracles.

Table 2.

Stations, groups, and cultural events in the 2016 procession.

3. Peruvians and Devotees: The Twofold Brotherhood and Its Staging

Celebrations of ceremonies and rituals are one of the areas of social life where the presence of symbols and practices interconnected with the unity of the social group of celebrants or supporters may be observed (Bryan 2016). In the case of the procession of the Lord of Miracles, this unity appears to unfold along two closely related dimensions. On the one hand, the idea of national unity is reflected and the sense of being Peruvians far from Peru; on the other, a religious unity associated with the devotion to the Lord of Miracles. These dimensions, national and religious, reappear throughout the route, often overlapping and intensifying each other. Below, we discuss ethnographic data that account for both types of symbolic references.

3.1. Peruvian Brothers: Music and Dance

Symbolic and ritual references to national unity are seen in a series of elements present in the procession. Here we will highlight only two. The first of these is the Peruvian National Anthem, which begins and ends the procession of the Lord of Miracles. In both cases, it is performed solemnly and with restrained emotion at the doors of the parish church of Sant Ramon Nonat (Figure 1). Those who sing the anthem repeat the same gesture: right hand on heart, gazing toward and beyond the image of the Christ himself who brings them together. The end of the last verse of the anthem is punctuated by cries of “¡Viva el Perú!” One of the most powerful and moving passages is worth noting here:

- We are free, may we always be so,

- may we always be so, […]

- For a long time the oppressed Peruvian

- dragged the ominous chain,

- Condemned to cruel servitude

- for a long time he quietly groaned. [1]

- But as soon as the sacred cry

- Freedom! on its coasts was heard […].

[Extract from the lyrics of the Peruvian National Anthem, Field note, October 2016]

Figure 1.

Brotherhood of the Lord of Miracles singing the Peruvian National Anthem, October 2017.

When listening to these verses, it must be remembered that, after the inauguration of the restored church in Lima (1955), a nationalist imaginary began to be forged around the Christ (Costilla 2016). The people of Lima, battered by the effects of the war and the subsequent crises that touched all levels of society found in the cult not only a realm in which to fortify their faith, but also a valuable reference for identity. On that basis, the symbol was used especially by a state in which the political, economic, and intellectual elites exalted their mestizo, or mixed-ethnic character, as a representation of a city and a nation founded on diverse cultural traditions. In later stages, this official religious symbol reinforced its place within the national religious landscape and was increasingly exhibited and recognized as a sign of the Peruvian nation and, at the same time, the tradition of its African heritage.

A second element, in which nationalism is clearly and forcefully expressed, is the importance of the Marinera dance in the procession (Tompkins 1981). Once the procession begins, the first dance in tribute to the Lord of Miracles is the Marinera (Figure 2). While the participating groups perform other dances along the route at different stations in honor of the Lord of Miracles, our ethnographic experience revealed that the Marinera is the dominant dance (Table 1 and Table 2) and the one most cheered by the celebrants, who normally end it with a “¡Qué viva el Perú!”

Figure 2.

Dancing the Marinera at the front door of the Church, October 2017.

This dance, with a female and male dancer facing each other but not touching, is especially popular on the Peruvian coast. Its characteristics depend on the variants, which include the Marinera Limeña, Norteña, Puneña, Arequipeña, and Andina. It is currently on the nation’s cultural heritage list and is for many “the queen and leading lady of all dances,” whose historical origins have made it a link to Peruvian nationalism. In short, it is a dance that plays a key role in many civic, military, and religious events held not just in Peru, but also abroad, where it takes on a special nature when performed. In the religious context of a procession, the dance only deepens the impression of how national and religious identities complement and reinforce one another.

3.2. The Manifest Nation: Consulate and the Flags

We want to point out that, in the procession in Barcelona, the station organized by the General Consulate of Perú is one of the most outstanding: it is the first station on the route and perhaps the busiest of them all (Station 1, Table 1; Station 2, Table 2). When the image of the Lord of the Miracles was there, the current Consul of Peru in Barcelona, Mrs. Franca Dezza Perruci, read a paragraph from the Bible about the passion of Christ and brought an arrangement made of red and white flowers to the Peruvian flag, which was placed at the bottom of image for the duration of the whole procession (Figure 3; Map 1). In 2013, the words spoken by the general consultant were recorded on the television program Món Latino and radio Mollet:

“The General consultant of Peru and all his staff, along with the family members, made appearance, to take tribute on the first station of this procession. Lord of the Miracles unites all the Peruvian women and men in faith, and unites us with those who accept us, and therefore, at this particular moment it is a universal faith, and simply, it is a way to give profound and honest tribute to Lord of the Miracles, the saint patron of Peru.”(Words of the consultant Franza Deza, October 2013)

Figure 3.

Current Consul of Peru at the first station with arrangement behind, October 2016.

Another way the importance of the nation is shown through symbols is the widespread and diverse use of the Peruvian flag. This Peruvian symbol is visible on the altar of the church during the Mass, at the entrance of the church where it is decorated with balloons and red-white textile, on the right side of the front door, and near the flower arrangement at the bottom of the Lord of the Miracles, as well as with other flags that they admire in the avenue through which the procession passes by. Anthropologists Ulla Berg and Carla Tamagno analyzed the experiences of the council advisory board (known as “Consejo de Consulta” in Peru) in Rome, Barcelona, Miami, and Paterson, concluding that it functions like “space of abilities and negotiation that produce and reproduce class, ethnic and gender hierarchy that guides social and public life of Peru, the same one that historically characterized interactions within society and status of this country” (Berg and Carla 2004).

The implementation of these activities, which symbolizes Peruvian status, implicates a certain institutionalization of transnational activities carried out by Peruvian migrants. Furthermore, Portes, Guarnizo, and Landolt claim that the concept of transnationalism implies that “…those movements and activities require regular and sustained social contacts through the national borders and reinforcement” (2003: 18). It also shows that, to approach transnationalism, we need to precisely establish and identify the main differences within power structures, such as multinational companies and states, and institutional powers which began as popular initiatives in the migrants’ home country (David 2008, 2009, 2012) These different actions, respectively, are called transnationalism “from above” and “from down.” The case that we are focused on is clearly an example of transnationalism “from down.”

3.3. Brothers (and Sisters) in Christ

Symbolic and ritual references to religious unity can also be seen in a series of other elements present in the procession. The first of these is the Hymn of the Lord of Miracles, where the bond of unity that this cult demands is demonstrated perhaps most clearly. This hymn is continually sung by the incense bearers who accompany the entire procession with their songs and, in a significant way, contribute to the beginning and the ending of the procession in the parish; it is sung with great respect and emotion by the brothers and sisters of the Brotherhood, as well as by all the congregants.

One aspect of the interpretation of the hymn that stands out the most is the clear association between the idea of being a good Christian and magnifying Peru:

- Lord of Miracles

- to you we come in procession

- your faithful devotees,

- to implore your blessing.

- With the firm step of a good Christian

- let us make Peru great

- And all of us united as a force we plead with you

- to shed your light upon us.

[Hymn of the Lord of Miracles, Field note, October 2016]

Additionally, the current hymn is one of the highlights in the recent history of the procession. As Costilla (2016) points out, the 1950s were a key moment because they coincided with the transition between two periods of the Peruvian Church: one (1930–1955) characterized by the emergence of a new militant laity, with symbols and songs seeking to instill feelings of belonging among Catholics; another (1955–1968) marked by two important episcopal councils that promoted a renewal of the Church. In consonance with these contexts, in 1955, the history of the cult reached two milestones that should be noted: first, the Brotherhood received the Archbishop’s official recognition, and second, the Hymn to the Lord of Miracles that is currently sung in the processions was selected.

A second element is the central symbol of this cult: the image of the Lord of Miracles, which has been replicated in countless material representations and has become a true sign for both those who are familiar with it as well as those who are not (Figure 4). This means that, in addition to its polysemic nature, it has achieved public recognition, including within the international religious arena, which grants it an unambiguous meaning: a sign of the Peruvian state as a mestizo nation and, at the same time, of the tradition of African heritage that unites migrant devotees wherever they are.

Figure 4.

Image of the Lord of Miracles, October 2016.

4. Dance Differences and Subverting Orders

As we have demonstrated, the dominant official language used by the various religious and political authorities who take part in the procession, as well as by the leaders of the participating associations and many of the celebrants, revolve around the figure of unity, which unifies the semantics of the brotherhood as devotees of the Lord of Miracles (religion) and as Peruvian brothers (nation). However, the procession is also a stage to represent and reproduce a series of differences related to this dominant language.

If we look at Table 2, we can see that, in 2016 and 2017, dances such as the Huayno, the scissors dance, the gypsy dance of the Virgin of the Gate, the agrarian celebration, a traditional Ecuadorian dance, and even the Salsa were performed. Additionally, groups such as the Lord of Miracles Volleyball Club and the Comando Svr Barcelona Grone of the Alianza Lima football club were also represented in the celebration. Nevertheless, the place of these performances within the procession, both spatially and temporally, as well as the types of interactions that occurred between the brothers who bore the image of the Christ and the members of these stations, attest to their secondary or marginal position relative to other more central stations, which normally revolve around national unity (like the stations of the Consulate, of the Marinera Association, etc.). Thus, although they are part of the ritual itself, they usually appear in the intermediate stations of the procession and take place in streets that are not completely closed off to traffic, which means the constant presence of and monitoring by the metropolitan police, among others.

To demonstrate this point, we will focus on two particular performances, the scissors dance and the Marian gypsy dance, because their staging clearly shows the differences within the celebration. To do this, we will examine their origin, the main characteristics, the position, and the relationship established with those in charge and with the image of the Christ in the procession.

4.1. From Sons of the Devil to International Dancers

The scissors dance has traditionally been performed by the inhabitants of the Quechua villages and communities of the south-central Andean Mountains of Peru. Although it is a typical Andean dance (Tomoeda and Millones 1998), for several decades, it has been performed by people from the urban areas of the country. This competitive ritual dance usually occurs during the dry season and its performance coincides with important phases of the agricultural calendar (Arce 2006). In the mountains, it is done from April to December at all the major agricultural and religious fairs. The scissors dance owes its name to the two rods of polished metal, similar to scissor blades, that the dancers carry in their right hand and that they move so as to make a particular metallic sound. The popularization of the name “scissors dance” is attributed to the writer José María Arguedas, who in 1962 published a story whose protagonist was one of these dancers (Álvarez 2007).

The dance is performed in groups comprising a dancer, a harpist, and a violinist. Each of the groups usually represents a specific community or village. In order to perform the dance, two ensembles and their dancers face off to the rhythm of the melodies played by the accompanying musicians. The dancers must strike the metal rods together and “fight” a choreographic duel of dance steps, acrobatics, and different movements. This is then followed by an individual sequence, where the dance steps increase progressively in difficulty. The duel between the dancers, called atipanakuy in Quechua, can last up to ten hours, and the criteria for determining the winner are the physical ability of the performers, the quality of the instruments, and the proficiency of the musicians who accompany the dance (Zevallos-Aguilar 2003).

The dancers, who wear outfits embroidered with gold stripes, sequins, and small mirrors, are forbidden to enter the grounds of the churches in this clothing because their abilities, according to tradition, are the result of a deal with the devil. In fact, it appears that the scissors dancers descend from the tusuq laykas, who were priests, diviners, and pre-Hispanic healers, and who were persecuted during the colonial period. It was in these times that they began to become known as supaypa wawan (“son of the devil” in Quechua) and to take refuge in the highest parts of the Andes. With the passage of time, the colonials accepted their return, on the condition that they dance to the saints and the Catholic God, although this instruction was not always accepted or obeyed, with their expressions of dissidence taking refuge to this day in this ritual dance in Peru (Montoya 2007). During colonial times, the dance was influenced by the steps of the Spanish jota, contradanza, and minuets, as well as by Spanish bullfighter costumes, thus acquiring its contemporary aesthetic. It was during this age that the scissors dance began to be performed at patronal festivals. Thus, it is currently a ritual dance that, through its choreography, represents pre-Hispanic entities such as pachamama, yacumama, hanaccpacha, ucupacha, and other wamanis, which has not prevented it from becoming a valued component of Catholic festivities.

During the 2016 celebration of the Lord of Miracles, this dance was performed at the station allotted to its practitioners (Figure 5) at the intersection of Sant Ramon Nonat Avenue and Cardenal Reig Street. This station was especially peculiar for several reasons. Firstly, its location was quite particular, as it was simultaneously the last station on Sant Ramon Nonat Avenue and the first one on Cardenal Reig Street. As pointed out above, the avenue is the nerve center of the celebration; the stations there are considered to be the most important for the celebrants for national and religious reasons. On the one hand, the stations that begin and end the procession are on this avenue. Additionally, it is at these stations where references to the idea of brotherhood as Peruvians and devotees of the Lord of Miracles (unity) become more evident at the symbolic and ritual level. In fact, it is in this avenue that the emotional excitement of the celebrants manifests itself in the clearest and most general way. However, the scissors dance station was far from being considered one of the most important of the celebration, and no major symbolic references to unity as Peruvian or devout brothers (as is the case with the singing of the Peruvian anthem, the Hymn of the Lord of Miracles, and the Marinera Dance) were made. This station was instead part of a logic of interaction that was closer to that of the stations located along Cardenal Reig Street and was one of the stations least regarded and attended by the bearers along the route. Moreover, only after this station were women allowed to bear the image of the Christ. The station’s transitional location seemed to render it a non-event.

Figure 5.

Dancers and musicians of the scissors dance. Rómulo Lliuyacc is dressed in yellow, October 2016.

Secondly, the very form of the station was also quite distinctive. Unlike most stations, it had no altar and no images of Christ, of the Lord of Miracles, of the Virgin, or of any saint. The station was made up of an improvised table comprising two chairs and a horizontal board covered by an aguayo or lliclla [2] of a predominantly black color and two bouquets of roses (intended for the Lord of Miracles) placed at the ends of the table. On the aguayo, there were several CDs and DVDs featuring both a musical duo playing Andean harps (known as the Zevallos Brothers) and a pair of dancers led by the principal dancer, Rómulo Lifoncio Lliuyacc. All DVDs were available for purchase and one could also book the musicians and dancers, while many wished to be photographed and mingle with both groups.

Returning to the procession and the performances of this peculiar grouping, the dancers completely occupied all of the space that was available. The dance simulated a competition where both dancers performed, demonstrating their acrobatic qualities. The first to dance was an adult member dressed in white. While he performed the dance, the sound of the metallic tapping of the scissors filled the place and the people applauded the eye-catching acrobatics. The second dance was performed by the older member, who interacted much more with the audience. He joked, laughed, graciously paused his dance to take photos, and more. It was a real spectacle and his skill in this area showed, with his ability to work a crowd particularly evident. The showman was the well-known dancer Rómulo Lifoncio Lliuyacc, the most famous Peruvian scissors dancer internationally; in fact, his stage name is “El Internacional.” Originally from Huancavelina, Peru, he has performed this dance professionally for more than 40 years. He starred in a 2002 documentary, entitled “The Dancers of the Holy Mountain,” which shows the historical importance of this dance, which is interpreted as a form of cultural resistance channeled through the body and its movements. In 2010, at the Casa Perú Siglo XXI, the first scissors dance competition in Barcelona was held to honor this seasoned dancer. That same year, the dance was recognized by UNESCO as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Given the importance of this dance as one of the most unique manifestations of the Andean culture of Peru and the acknowledged prestige of one of its principal international proponents, the stop made by the procession of the Lord of Miracles was especially quick and cold on the part of the brothers toward those at the station. In fact, the principal bearers of the Christ did not pay much attention to the scissors dance performed in honor of the Lord of Miracles, and even less to the jokes that the showman made. At the end of his performance, Rómulo stood before the image of the Cristo moreno and addressed the bearers directly to implore them to offer him a few words of thanks, as the representatives of all stations normally do during the procession. However, his words were interrupted by these same bearers who, without waiting to hear the end of his message, sounded the bell that gave the order to continue with the procession, on the grounds of running behind schedule. In the end, the scissors dance station was not included in the 2017 procession. Yet again, the scissors dance and its performers, branded as devilish during colonial times, was not able to achieve full acceptance by the ruling Catholicism—though this time by Peruvians themselves, in the 21st century and on European soil.

4.2. Marian Gypsy Dancing to the Cristo moreno

At the 8th station of the procession, gypsies of the Virgen de la Puerta de Otuzco, perform a dance. It is a characteristic dance of slavery, Trujillo doors, located in Northern Peru. Usually, it is performed in the same zone, during the celebration of Virgen of Otuzco, between the 12th and 16th of December. This had a colonial origin, but the arrival of Spanish conquistadors and colonists brought the cultural influence of Mozárabes, which were present in Europe since 1425.

Even though diverse versions of the story of celebration origin exist, it probably began in 1554, when a group of religious Augustinians from Orozco (Spain) settled in this zone. Six years later, they formed a village, Inmaculada Concepción de la Virgen of Copacabana, Otuzco, and dedicated their temple to the Virgin, which they brought. It is known that, in 1664, the bishop of Trujillo, Monsignor Juan of the street, made official the episcopal celebration of the Virgen of Otuzco on the 15th of December. In its beginnings, the Virgin was accompanied by the figure of Inmaculada Concepción, which was a little bit smaller and used in smaller celebrations. This second image was located on the main doors of the church that gained the name Virgen María de la Puerta, later known as “Virgen de la Puerta” due to its location. The tradition is that its miraculous character finally turned into central Virgen of the festivity, even though this information could not be validated historically (Millones 2010, p. 196). In 1943, with Congreso Eucaristico celebrated in Trujillo, the inauguration and worship of Virgin de Otzco (also called “mamita”) was authorized and she was named Reina del Norte del Peru and Patrona de la Paz Munidial. Finally, in 2012, the festivity was declared the Patrimonio Cultural de la Nación. Historically, the cult of Virgen de la Puerta in Otuzco, have carried out a series of dances, three of which attract attention: las collas, los negros, and las gitanas. Even though in an earlier time the majority of the dances were considered pagan by the clergy, later on they were accepted. Millones agrees that this festivity was part of a devotion of those in the north cost that has a very distinct history from devotion to the Andean land in the center and south of Peru, where the centers of power of pre-Hispanic [note: is there a word missing here?] put pressure on Spanish evangelizers so they would give Andean traditions a place in their worship cult. On the other hand, in the north, native traditions and languages disappeared rapidly, facilitating the process of Christianization.

In the case of the gypsy dance, it was incorporated between 1926 and 1928 into the festivity. There is no prior existing information about its presence, although some verbal stories claim the contrary. According to their members, the dance was invented by Señor Cruzado. Although it is currently one of the traditional dances of the festivity, Millones (2010) indicates that it is still considered foreign since it comes from the distant era of slavery. From its beginnings, the dance was performed by mestizos who, with their costumes and movements, challenged the “gypsies” that arrived with their tents to dwell in the area. The annual pilgrimage, until the Virgen de la Puerta, was also similar to the mobility that characterized a gypsy village. Nowadays, the dance is usually only performed by women, accompanied with a drum and accordion, which set “quimboso” (how it’s usually said in Peru) rhythm. Finally, they usually send a message or sing to honor the patron of the festivity.

As we pointed out above, in the procession of the Lord of Miracles in Barcelona, the association of “Baile Gitanos de la Virgen de la Puerta” owns the 8th station. The main celebration of this dance is the festivity that honors the same Virgen de la Puerta celebrated in December in a neighborhood called Raval, in Barcelona. They have a very privileged place in the city. Nevertheless, the place during the celebration of the Lord of Miracles is dependent. This fact is expressed in the position that it has during the procession (Map 8) and in the interaction by the members with the image of Christ when they visit the station, which we will show below.

After one person in the procession speaks a few Biblical words (passion of the Christ) to the image of the Lord of Miracles, the group seize the place and start to perform the dance. Weak and monotone melody is projected by a loud speaker and the gypsies start to dance to the rhythm of the music in front of the Christ. While they dance, the dancers wear their flowery skirts, colorful veils, and brilliant headbands (Figure 6). Later on, as they continue moving, they walk around closer to the worshiped image. A small group follows the dance with the palm leaf, and in between them, some people that seems to be family members of the dancers. The majority do not follow the dance with the palm leaf a lot, which shows us that they are not familiar with it. This does not seem to be a circumstantial thing associated with a particular context. In fact, the difference between other performed dances in the procession such as la marinera, the Peruvian waltz, and the huayno, which are very well known and often practiced by a large number of Peruvians in their country and abroad, is that the dance of the gypsies is characteristic for the celebration of the Virgen de la Puerta in Otuzco and typical in Northern Peru. This, combined with other details, gives us insight into the type of the interaction that is generated in this station.

Figure 6.

Dancers of the Association of Gypsies of the Virgen de la Puerta. October 2016.

Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that, although the interaction that takes place between the group of dancers and the rest of the celebrants at this station is much less intensive than at the one located on Sant Ramon Nonat Avenue, to finalize the presentation, one of the dancers has the opportunity to carry the image of the Lord of Miracles through Cardenal Reig Street, taking on the role of a protagonist in the procession (Map 8).

Besides that, we want to point out one symbolic aspect that allows us to establish a difference between this station and the station of the scissors dancers. Unlike the last station, at the gypsy station, there is an altar covered with purple veils, with two candles, a flower arrangement, and the Virgen de la Puerta located in the center, as a patroness of the gypsy community from Latin America. United by nationalism and popular Catholicism, the Peruvians pay tribute to both images on this processional journey, in such a way that if difference exists between the two, it is well balanced and not as visible as it is in the case of the scissors dance.

5. Discussion

Over the course of our research, we were able to observe two phenomena. We have shown how the Brotherhood of the Lord of Miracles and its supporters organize a large proportion of their actions and communications under the logic of unity. During the procession, this is acted out in different ways: on the one hand, the vast majority of celebrants and attendees of the procession are of Peruvian origin. Under this umbrella, a series of elements referring to their Peruvianness are deployed, constantly reinforcing this unitary bond during the celebration. On the other, the participants and supporters of this cult are seen and described as “brothers in Christ,” elevating the brotherhood attached to the cult of the Lord of Miracles as the main tie among them. Furthermore, both references to unity can be expressed simultaneously and stir up strong emotion in devotees (as with the Hymn of the Lord of Miracles), which symbolically and ritually reinforces this unity. This is especially significant as the ritual staging takes place in a public space where Peruvians and devotees congregate in a space that is far removed from their origin, which is ritually re-appropriated by the celebrants, as happens with the Peruvian diaspora that congregates ritually at the global level to worship the Cristo moreno (Paerregaard 2008).

Second, we have also shown that in parallel to this series of elements that insist on the idea of unity, brotherhood, and the supposed equality of celebrants and participants, the procession shows clear signs of the great differentiation and inequality that exists between the various social and cultural groups that participate in it. This distinction is clearly expressed in the spatiotemporal organization of the stations and in the types of interactions that exist between the various social groups that preside over the stations of the procession and the members that bear the image of the Lord of Miracles. We have demonstrated this through analysis of the scissors dance, a performance that plays out the presence of differences that cause tension in or question the homogeneity of the aforementioned unity. It is a practice that has been substantiated by a series of studies on cultural resistances that have arisen from contexts where a long colonial and republican domination has occurred, such as in Peru (Rostworowski 1992; Tomoeda and Millones 1998), but this time they are re-enacted in the context of global diaspora.

The procession of the Lord of Miracles is a public ritual that gathers together Peruvians in Barcelona. We hypothesize that the incorporation of these diverse groups into the structure of the procession in Barcelona attempts to acknowledge the diversity of sociocultural manifestations (regional, religious, musical, dance, and sporting activities) that partially represent the Peruvian residents in Barcelona. However, this does not ensure that they do not challenge the unity that the brotherhood and many of the celebrants try to carve out ritually. In this setting, we consider that examining the symbolic and ritual specificities of the procession of the Lord of Miracles in Barcelona sheds light on the reconfigurations of the spatial and temporal horizons of diasporic religion, and how this can help us make sense of the economic, cultural, and social circumstances that often challenge globalization (Levitt 2001; Vásquez 2008; Levitt and Schiller 2004). This is especially the case in the context of wider debates on the place of ethnic and religious minorities in contemporary urban societies, which are often defined generically as secular (Casanova 2007).

6. Materials and Methods

In this study, we used an ethnographic methodology because we consider it to be a particularly suitable means of approaching the stagings and interactions that unfold throughout the procession since it allows for direct contact with the actors involved and interaction (Willis and Trondman 2002; Flick 2002), as well as a description and analysis of events (Kalocsai 2000). The fieldwork was conducted during 2016 and 2017 as part of the research project “I+D-Excelencia CSO2015-66198-P: The Place of Religion in Open Urban Spaces: A Comparative Case Study of Public Religious Acts and Celebrations in Madrid and Barcelona (EREU-MyB).” In this project, the authors of this article focused on studying the procession held by the Brotherhood of the Lord of Miracles of Barcelona in honor of the Cristo moreno. This brotherhood was founded in July 1992 by two Peruvian devotees with the dual aim of propagating the original cult of the Lord of Miracles in Peru and bringing together Peruvians living in Barcelona. Currently, the brotherhood welcomes both Peruvian men and women as well as their descendants, with distinct roles within the organization (confreres, incense bearers, etc.), and there is a committee that coordinates the celebration of the festival every year. The procession takes place in October in the neighborhood of Les Corts in Barcelona, in the vicinity of the Church of Sant Ramon Nonat, which hosts the brotherhood and has also housed the image of the Cristo moreno throughout the year since 1997. The primary means of data collection was observation of this event. However, documentary material related to the celebration in general and the procession in particular, as well as that on the brotherhood (especially websites), was also collected and analyzed. All the information collected was reviewed and analyzed through content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon 2005).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Spanish government for contributing to the funding of this research through the project “I+D-Excelencia CSO2015-66198-P: The Place of Religion in Open Urban Spaces: A Comparative Case Study of Public Religious Acts and Celebrations in Madrid and Barcelona (EREU-MyB).” We would also like to thank the Brotherhood of the Lord of Miracles of Barcelona for facilitating our research work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

References

- Altamirano, Teófilo. 2000. Liderazgo y Organización de Peruanos en el Exterior: Culturas Transnacionales e Imaginarios Sobre el Desarrollo 1. Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, Jannet. 2007. La danza de las Tijeras en El sexto by José María Arguedas. Contribuciones Desde Coatepec 12: 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- Arce, Manuel. 2006. La danza de tijeras y el violín de Lucanas. Lima: Fondo Editorial Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. [Google Scholar]

- Banchero, Raul. 1972. Lima y el Mural de Pachacamilla. Lima: Editorial Jurídica. [Google Scholar]

- Banchero, Raul. 1995. Historia del Mural de Pachacamilla. Lima: Consejo Directivo del Monasterio de las Nazarenas Carmelitas Descalzas. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, Ulla, and Carla Tamagno. 2004. El Quinto Suyo: Conceptualizando la diáspora peruana desde abajo y desde arriba. Las Vegas: Mimeo. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, Dominic. 2016. Ritual, identity and nation. In Remembering 1916 The Easter Rising, the Somme and the Politics of Memory in Ireland. Edited by Richard S. Grayson and Fearghal McGarry. Cambridge: University Press, pp. 24–42. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 2007. Immigration and the New Religious Pluralism: A European Union/United States Comparison. In Democracy and the New Religious Pluralism. Edited by Th Banchoff. Oxford: Oxford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Costilla, Julia. 2016. Una práctica negra que ha ganado a los blancos: Símbolo, historia y devotos en el culto al Señor de los Milagros de Lima (siglos XIX–XXI). Anthropologica del Departamento de Ciencias Sociales 34: 149–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- David, Ann R. 2008. Local diasporas, global trajectories new aspects of religious ‘performance’ in British Tamil Hindu practice. Performance Research 13: 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, Ann R. 2009. Performing for the Gods? Dance and embodied ritual in British Hindu worship. Journal of South Asian Popular Culture 7: 217–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, Ann R. 2012. Sacralising the city: Sound, space and performance in Hindu ritual practices in London. Culture and Religion 13: 449–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, Uwe. 2002. Qualitative Research—State of the Art. Social Science Information 41: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbin, David. 2012. Introduction: Believing in the city. Culture and Religion 13: 401–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houseman, Michael. 2012. Le rouge est le noir. Essai sur le rituel. Toulouse: Presses Universitaires du Mirail. [Google Scholar]

- Houseman, Michael, and Carlo Severi. 2009. Naven ou le donner à voir. Essai d’interprétation de l’action rituelle. Paris: Fondation de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme/CNRS. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Hsieh, and Sarah E. Shannon. 2005. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15: 1277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalocsai, C. 2000. The Multi-sited Research Imaginary: Notes on Transnationalism and the Ethnographic Practice. Paper presented at Comparative Research Workshop, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA, December 4. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, Peggy. 2001. The Transnational Villagers. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, Peggy, and Nina Glick Schiller. 2004. Conceptualizing Simultaneity: A Transnational Social Field Perspective on Society. The International Migration Review 38: 1002–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlister, E. 1998. The Madonna of 115th Street revisited: voudou and Haitian Catholicism in the age of transnationalism. In Gatherings in the Diaspora. Religious Communities and the New Immigration. Edited by R. S. Warne and J. Wittner. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, pp. 123–60. [Google Scholar]

- Merino, Hernando. 2002. Historia de los Inmigrantes Peruanos en España. Dinámicas de Exclusión e Inclusión en una Europa Globaliza. Madrid: CSIC. [Google Scholar]

- Millones, Luis. 2010. La Cruz del Perú. Lima: Pedagógico San Marcos—Fondo Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Montoya, Rodrigo. 2007. El buen danzante de Tijeras recoge agua con canasta. Investigaciones Sociales 19: 15–54. [Google Scholar]

- Paerregaard, Karsten. 2002. Business as Usual: Livelihood Practice and Migration Practice in the Peruvian Diaspora. In Mobile Livelihoods. Life and Work in a Globalized World. Edited by Karen Fog Olwig and Ninna Nyberg Sorensen. London: Routledge, pp. 126–44. [Google Scholar]

- Paerregaard, Karsten. 2005. Inside the Hispanic melting pot: Negotiating national and multicultural identities among Peruvians in the United States. Latino Studies 3: 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paerregaard, Karsten. 2008. In the Footstpes of the Lord of Miracles: The Expatriation of Religious Icons in the Peruvian Diaspora. Journal of Ethic and Migration Studies 34: 1073–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostworowski, Maria. 1992. Pachacámac y el Señor de los Milagros. Una Trayectoria Milenaria. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. [Google Scholar]

- Ruíz Baia, Larissa. 1999. Rethinking Transnationalism: Reconstructing National Identities among Peruvian Catholics in New Jersey. Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 41: 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Tomoeda, Hiroyasu, and Luis Millones. 1998. El mundo del color y del movimiento: De los takis precolombinos a los danzantes de Tijeras. In Historia, Religión y Ritual de los Pueblos Ayacuchanos. Lima: National Museum of Ethnology Repository, pp. 129–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins, William David. 1981. The Marinera, Musicology. In The Musical Traditions of the Blacks of Coastal Peru. Los Ángeles: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez, Manuel A. 2008. Studying Religion in Motion: A Networks Approach. Method & Theory in the Study of Religion 20: 151–84. [Google Scholar]

- Werbner, Pnina. 2002. The place which is diaspora: Citizenship, religion and gender in the making of chaordic transnationalism. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 28: 119–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, Paul, and Mats Trondman. 2002. Manifesto for Ethnography. Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies 2: 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zevallos-Aguilar, Juan. 2003. José María Arguedas’s Representation of la danza de las Tijeras: A Contribution to the Formation of Andean Culture. In Musical Migrations: Transationalism and Cultural Hybridity in Latin/o America. Volume I. Edited by C. Jáquez. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 131–46. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).