1. Introduction

The rapid development of house churches is a significant characteristic of Christianity in China in recent years. However, there are still no official statistics concerning the exact number of house churches and believers in China. Yu Jianrong, who has been studying house churches in China for many years, mentioned in two speeches in Peking University in October and December 2008 that there are approximately 18 million to 30 million believers of the Three-Self Church and 45 million to 60 million believers of house churches. Li Fan, chief of a civil organization called “World and China”, said in a conference on religious affairs in Singapore that there are currently approximately 0.8 million house churches, and that house churches have expanded on a significant scale in China. Especially since the 21st century, the number of urban Christian house churches has been increasing rapidly (

Yang 2015). It therefore begs the questions, what characterizes the house churches of urban China, and what characterizes these house church followers? How did they choose between the Three-Self churches and house churches? These are all valuable research directions to pursue.

Protestant Christianity (in the following article referred to as Christianity) was brought to China by British missionary Robert Morrison 210 years ago (

Yang 2010). During the 19th century, Christianity began to spread in coastal areas in China, through the efforts of Christians such as Morrison. In its heyday, more than 130 foreign missionary societies from Britain, America, Canada, and other countries contributed to this spread of Christianity (

Li 1998). In the 1910s, the Qing Dynasty was overthrown and the Republic of China was formed, and formal, systematic church development unfolded all over China. Christianity has contributed much to the development of educational, cultural, and medical institutions of China during that historical period. Since the 1920s, in coastal areas such as Guangdong and Fujian, as well as in major cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, religious activities based on family as a unit began to appear. These small-scale family gatherings are actually rituals and worship activities held at home, which is not to be confused with the “house churches” that are discussed in this article (

Bays 2011). After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, how to treat Christianity, a foreign religion, became the major issue in Chinese religious policy. On 28 July 1950, Wu Yaozong and 40 other major figures in Christianity published “The Way for Chinese Christianity to Work for the Construction of New China” (or The Christian Manifesto). They proposed that Chinese Christianity should achieve the goals of “self-governance”, “self-sufficiency”, and “self-dissemination” in the shortest amount of time to create a church that is entirely run by Chinese people. The publication of this declaration marks the beginning of the Three-Self Patriotic Movement. In July 1954, the Three-Self church was officially founded. It is a church that supports the People’s Republic of China government and the country’s ruling party, the Chinese Communist Party. It rejects any administration or intervention from foreign churches and firmly holds the principles of self-governance, self-sufficiency, and self-dissemination. The Three-Self church is the only legal Christian church in the country (

Landryderon 2011). Since the 1950s, it has been the principal institution through which Christianity is spread in China. Because of the government’s prohibition of any missionary work outside of the Three-Self church, house churches gradually became hidden and their activities went underground. During the Cultural Revolution, all forms of religion, including Taoism, Buddhism, Islam, and Christianity, were severely persecuted, and the Three-Self church was practically paralyzed. Thus, house churches became the dominant sites where Christianity was practiced (

Nie 2000).

After December 1978, China went through a series of economic reforms, and the freedom of faith was reestablished. Christianity thus gained another opportunity to spread in China. As the Chinese government gradually loosened its religious policy, old Christian churches were reestablished, and new ones expanded rapidly (

Aikman 2003). At the same time, house churches also bloomed, especially in urban areas. The expansion of house churches can be attributed mainly to three reasons: some believers are not convinced by the Three-Self church’s explanation of Christianity, some are not willing to be under the regulation of the government, and some find it inconvenient to attend activities organized by the church.

It is worth noting that after the foundation of the People’s Republic of China, the official definition of a “house church” within the country became different from the traditional definition in the Christian world. According to China’s Regulations on Religious Affairs, all constructions of religious sites and organizations of religious activities must be registered under the concerned government department—The People’s Republic of China State Bureau of Religious Affairs. The Bureau states that all religious sites that are not registered are seen as “house churches”. In other words, in China, house churches are religious sites which do not fulfill the duty of self-registration and which exist without the government’s permission. They exist outside the frame of “legal religious activities”. To some degree, house churches are illegal. In urban China, these religious sites that are not registered under the government can be homes of certain believers, or office buildings or private homes rented or bought by believers.

2. Literature Review

There have been various perspectives on why Christian house churches have expanded rapidly in China in recent years. Several scholars believe that since the economic reform in China, changing institutions have created a favorable environment for the development of house churches.

Fan (

1998) identified large-scale population migration, increasing complexity in residential environment, and plurality within residential communities as important factors for the fast development of Chinese house churches. A study by

Liang (

1999) showed that, since the economic reform in the 1980s, house churches emerged in large numbers in rural areas in China, rapidly spreading Christianity across rural villages. Other studies indicate that due to the Chinese government’s restoration of the principle of religious freedom, policies regarding religions have been relatively lax, making it possible for house churches to survive and thrive (

Gao 2005;

Yu 2009).

Zuo (

2012) agreed that Chinese government officials have become aware of the positive effect of religions on increasing people’s sense of security and mental happiness, thereby increasing the harmony and stability of society. Therefore, the government’s tolerance of diversified development within the religious realm has contributed to the prosperity of house churches.

Yu (

2013) believes that the transition from economic socialism to a market system has caused a series of transformations in politics as well as economics. The Chinese people’s culture and worldviews have undergone constant challenges, and pluralism has been on the rise. The coexistence of pluralist cultures has also led to changes in the Three-Self church’s domination in China and encouraged the development of house churches.

Other scholars considered the rise of house churches to be a result of the dynamics within the religious market of China. For example,

Yang (

2008) proposed that in China, three kinds of “religious markets” coexist: the “red market”, the “black market”, and the “grey market”. The so-called “red market” refers to the religions acknowledged by the government, including all legal religious organizations, believers, and religious activities. The “black market” refers to religions that the government bans, including illegal religious organizations, believers, and religious activities. The “grey market” refers to the grey area between the legal and the illegal, composed of religions, spiritual organizations, activities, and believers that have ambiguous legal standing. Because of a lack of competition and strict governmental regulations, the fully legal “red market” cannot satisfy Christians’ needs. Yet, the “black market” or illegal religious services face harsh governmental policies and punishments and can barely survive. Therefore, the “grey market” develops quickly in China.

Another perspective is drawn from studying Christianity’s general development around the world, and therefore, claims that the revival of the house church is a natural result.

Li (

2012) believes that a number of religions around the world exhibit the common trend of informal religious institutions and activities emerging alongside formal institutions, complementing each other.

Yu (

2013) maintains that in order to adapt to the profound transformations taking place in China in various realms from politics and economics to culture and society, Christianity has evolved along pluralistic paths. The revival of house churches is a result of this divergent evolution of Christianity. On the other hand,

Goldstein (

2017) believes that Christianity in China has accumulated many conditions for change in the form of expansion throughout history, such as different understandings of religious doctrines, or charismatic leaders with strong influential power and leadership. Therefore, believers’ diverse needs for different approaches to Christianity has propelled the development of house churches.

It is critical to differentiate between house churches in the urban area and those in the rural area, according to many scholars.

Cheng (

2003), for example, wrote that the rise of urban house churches in the 1990s accompanied the rapid economic and social development of cities, which is unrelated to the expansion of rural house churches in the 1980s.

Zimmerman-Liu and Wright (

2015) supported this view, further suggesting that the social upheavals and transformations strongly impacted urban residents’ lives in various aspects, and Christianity helped to ease the anxiety and stress of social changes. Urban house churches thus expanded rapidly. Scholars characterized this kind of house church as “the new mode of urban house church”, namely, the kind of house church that appeared in China since the 1990s, following the traditions of house churches in China, mainly constituted by younger generation of intellectuals (

Homer 2010;

Hong 2012).

Chow (

2014) reported that, as China’s social connection with the world continues to grow, more and more Chinese people get to know and are converted to Christianity through studying abroad or making foreign acquaintances, which explains the large proportion of urban elites with international education experiences within the community of house church organizers.

In short, the relevant literature displays the many attempts made to explain the rapid growth of house churches, both against the background of social development in China since the economic reform, and from the perspective of the internal dynamics of Christianity. These explanations are, however, on a large scale and lack empirical quantitative evidence at the meso-level. This article thus aims to discuss the reasons why urban Christians choose certain sites for religious activities, by comparing house churches with Three-Self churches, from the perspective of individual Christians through survey data obtained in the city of Wuhan in China.

3. Research Data and Method

3.1. Introduction to the Data Collection Process

The data analyzed in this article were retrieved from the “China urban residents’ religious belief survey” initiated in 2015 by the China Urban Ethnic and Religious Affairs Research Center in the city of Wuhan. China Urban Ethnic and Religious Affairs Research Centre is a research center jointly established by the State Ethnic Affairs Commission (SEAC) and South-Central University of Ethnicities, focusing on ethnic and religious issues in urban China. This research is completed with the assistance of China Urban Ethnic and Religious Affairs Research Centre, SEAC and the Ethnic Affairs Commission of Wuhan. Wuhan is one of the largest cities, both in terms of population geographic area in the middle region of China, as well as one of the earliest cities to be penetrated by foreign missionaries. By the 1830s, some of the earliest churches, such as Gefei Church, Hualou Church Headquarters, Rongguang Church, and Hanyang Church, were established in Wuhan (W). According to incomplete statistics, by 2014, the number of registered Christians reached 80,000 in W, with 113 Three-Self churches and 91 house churches and similar informal religious practicing sites. In recent years, Wuhan has also witnessed a rapid development in house churches. For example, in terms of the number of newly converted Christians, the percentage of those converted at a house church has increased from 18% in 2010 to 33% in 2013, out of all newly converted Christians in Wuhan in those respective years.

This survey applies a four-level random sampling method. On the first level, the sum of urban subdistricts is treated as the primary sampling population, and the 11 districts are viewed as units for systematic random sampling. On the second level, the sum of residential committees is treated as the sampling population, and simple random sampling is conducted. On the third level, the sum of families is treated as the sampling population, and simple random sampling is conducted. On the fourth level, the sum of citizens aged 16 years and above in each family are treated as the sampling population, and simple random sampling is applied. In this survey, researchers distributed 6000 questionnaires and collected 4929 questionnaires, with a collection rate of 82.15%. After removing invalid questionnaires, we retained a total of 4092 valid ones.

Of the 4092 valid questionnaires, 889 residents clearly indicated that they follow a certain religion, accounting for 21.73% of total respondents. Of these respondents with religious faith, Buddhism, a traditional religion of China, has the most followers, reaching 14.69% of the total respondents. Christianity (117 respondents) and Islam (67 respondents) are the second and third largest religions, reaching 2.86% and 1.64%, respectively.

3.2. Research Method

We conducted descriptive statistical analysis on the 117 Christians, in terms of basic information including age, gender, ethnicity, and education, as well as the reason they chose certain sites for religious practice, the distance between their residential site and religious practice site, and the flow between sites for religious practice.

Apart from statistical analysis, we also randomly chose four respondents from each district to conduct in-depth interviews, totaling 44 participants. We recorded their opinions about “Three-Self churches” and “house churches”, their reason for choosing their current religious practicing site, their relationships with the pastor and fellow Christians, and their views on the activities and organization of their church.

In addition, we also interviewed five managers of Three-Self churches and five managers of house churches. Through these interviews, we tried to gain a deeper understanding of the churches’ relationship with local governmental offices that are in charge of religious affairs, their managerial organization, their current situation with religious activities, the fluctuation of membership, and by what means they have tried to absorb new members.

4. Survey Results Based in Wuhan City

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of Urban Christians

Table 1 is a descriptive summary of the studied Christians’ collective characteristics, and a basic comparison of members of Three-Self churches and house churches. We were concerned about the truthfulness of the interview response and have been considering the problems of whether the interviewees know to which category their churched belonged, and whether house church attendees would refrain from reporting the truth. In order to minimize the errors incurred, we compared the interviewees’ response of which church they usually attend to the list of Three-Self and house churches provided by the Wuhan city government, in order to determine whether they have attended Three-Self or house churches. Of the 117 Christians in the study sample, 65 of them attend religious services in Three-Self churches (55.56%), while 52 attend religious services in house churches (44.44%). Members of the two types of churches do not show remarkable difference in gender, ethnicity, political affiliation, or income, but some significant differences exist in terms of age, marital status, education, and institution of employment.

For age, house churches generally have a more youthful age structure than Three-Self churches. Specifically, 11.54% of house church members are under the age of 35 years while 42.30% are over the age of 60 years. In comparison, 6.15% of Three-Self church members are under 35 years while 53.85% are over 60 years.

For marital status, singlehood is slightly more prevalent in house churches, as 11.54% of house church members are single while only 7.69% of Three-Self church members are.

For education, house churches are comprised of a higher proportion of both the highest and lowest educational levels. Of Three-Self church members, 24.62% are Christians who have received education at the primary school level or lower, compared to 36.54% of house church members. On the other end of the scale, 9.22% of Three-Self church members have received education at the university level or higher, compared to 17.31% of house church members.

Concerning the institution of employment, Christians who work at state/collective-owned enterprises take up a greater proportion in Three-Self churches, while employees of private enterprises and foreign investment enterprises make up a greater proportion in house churches. In Three-Self churches, 19.65% work at state/collective-owned enterprises, while in house churches the number is only 9.62%. In contrast, 61.54% and 11.54% of house church members work in private and foreign investment enterprises, respectively.

4.2. Further Analysis of Urban Christians’ Choice of Site for Religious Practice

4.2.1. Knowledge of Sites of Religious Practice

In order to assess church members’ knowledge of the difference between house churches and Three-Self churches, we designed the question “To which category does the church that you are currently going to belong?”, with three options “registered (Three-Self church)”, “unregistered (house church)”, and “I don’t know”. The results show that “Three-Self church” was selected 87 times, accounting for 74.36%, “house church” was selected by 22 people, accounting for 18.80%, and “I don’t know” was selected by eight people, accounting for 6.84%.

There are, however, some discrepancies between the category that participants selected and the category into which the government agency of religious affairs in Wuhan placed the given churches. After comparison, we discovered that 28 respondents mistook house churches for Three-Self churches, and five mistook Three-Self churches for house churches. Among the eight people who did not know to which category their churches belong, seven attend house churches and one attends a Three-Self church. All in all, besides the 6.84% that lack knowledge of the category of their churches, 28.21% of respondents were misinformed about the category of their church. Thus, 35.05% of all respondents did not find it necessary to know the category of the church before choosing it as their site for religious practice.

4.2.2. Arriving at the Church for the First Time

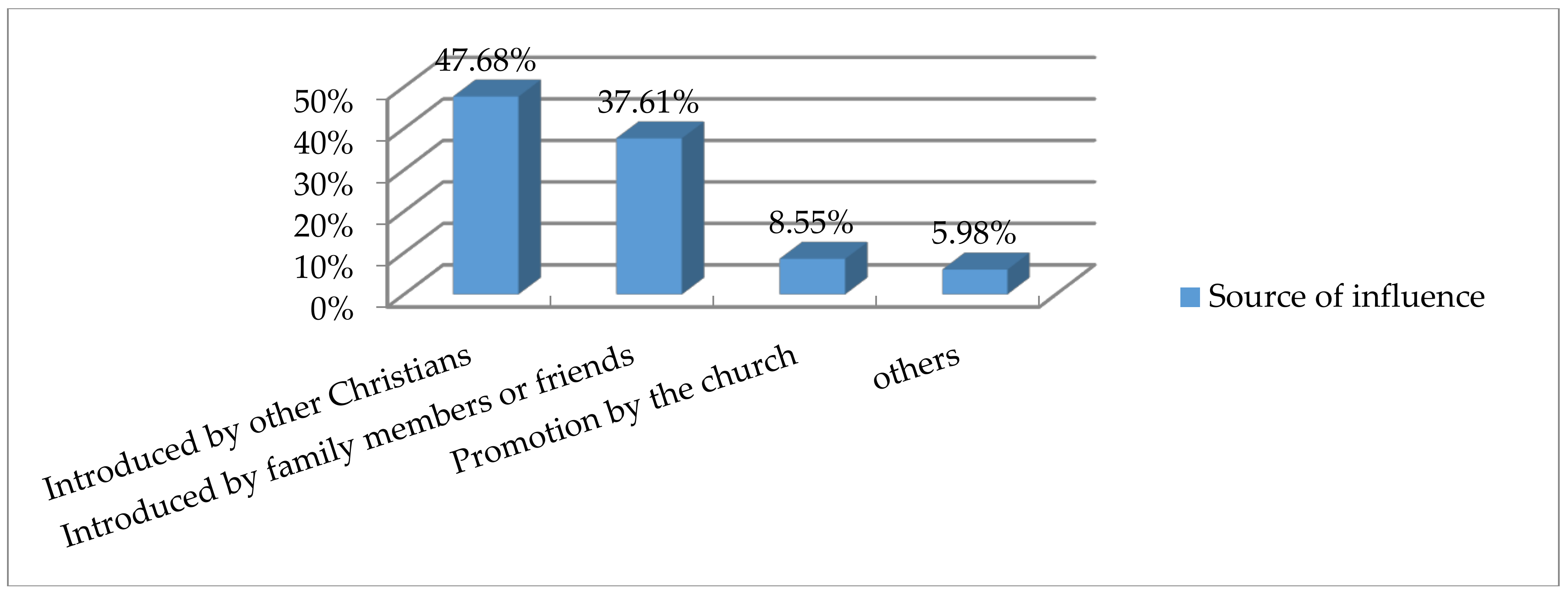

In order to understand how they first approached their church, we designed the question, “What made you first approach your church?” The results are shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows the source of influence that prompted the respondents’ first approach to their current church. The results show that 47.86% were introduced by other Christians and 37.61% were introduced by family and friends, while 8.55% were attracted by promotion by the church and 5.98% came for other reasons. It can be seen that Christians are heavily influenced by their social network, and church promotion had some effect as well.

4.2.3. The Relationship between Choice of Religious Practice Site and Residential Site

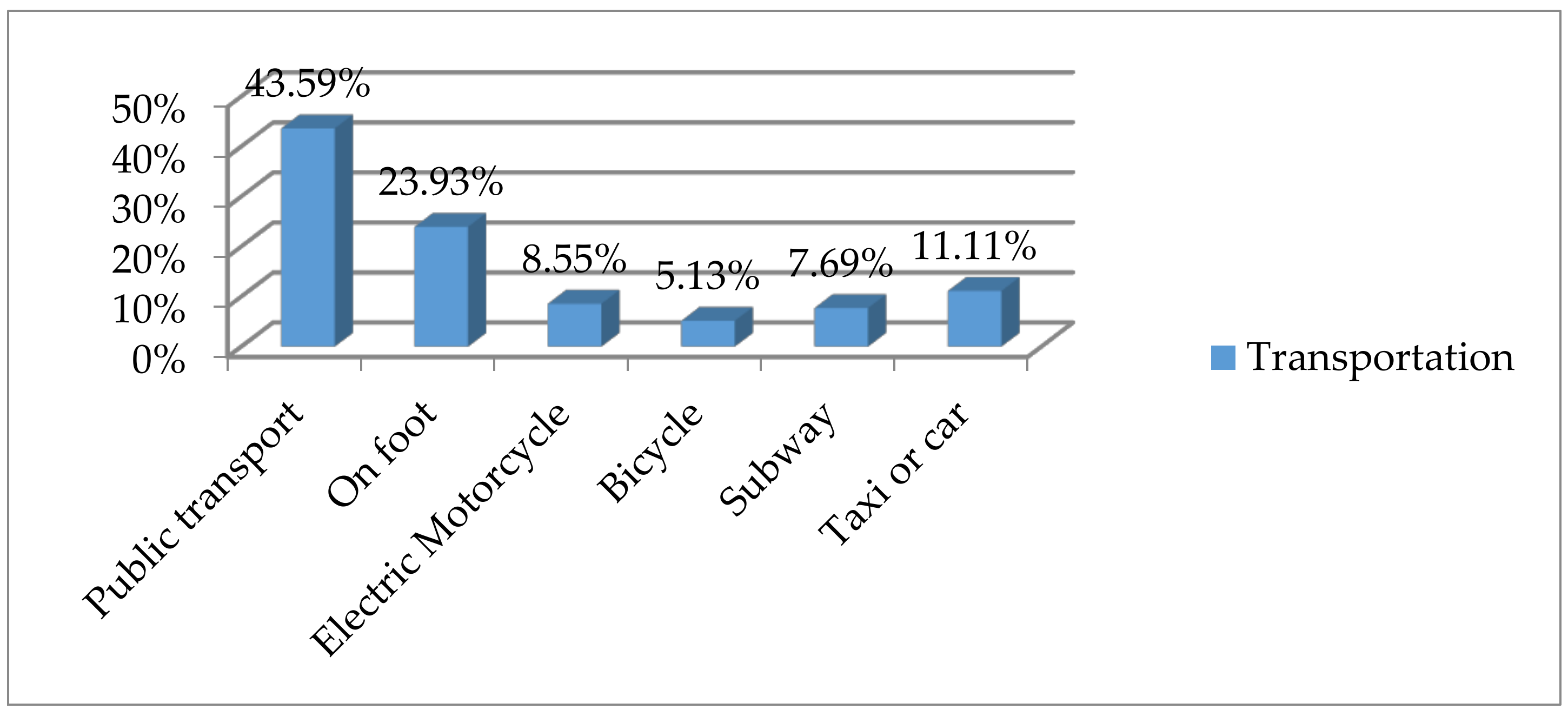

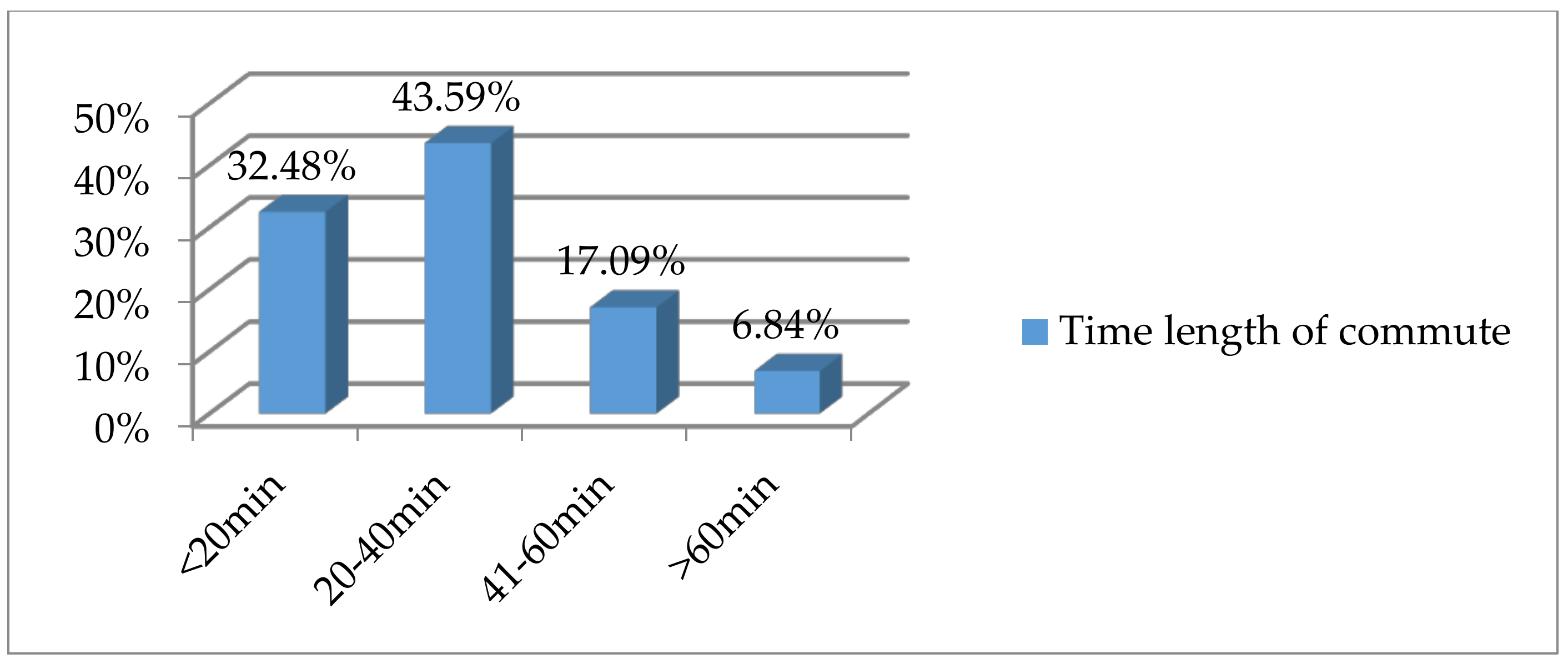

In order to understand the relationship between choice of worshipping site and residential site, we designed two questions: “By what means do you travel to your site of religious practice?” and “How long does it take for you to travel to your site of religious practice?” The survey results are as follows.

Figure 2 reveals that the two most popular means of transportation are public transport and on foot, accounting for 43.59% and 23.93%, respectively. The least popular means are subway and bicycle, accounting for only 7.69% and 5.13%, respectively.

Figure 3 reveals that most people spend up to 40 min to commute to their place of worship. Specifically, 32.48% of the respondents spent less than 20 min to commute to their church, and another 43.59% spend 21–40 min. In comparison, only 6.84% spent more than an hour on transportation. A preliminary conclusion drawn from

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 is that Christians take geographical distance into consideration when choosing their place of religious practice. Churches in proximity to the believers’ residences are more likely to attract them.

4.3. Analysis of the Flow of Christians between Places of Religious Practice and Reasons

4.3.1. Survey of Flow of Urban Christians

In order to understand the flow of urban Christians between different churches, we designed the section headed by the question “Have you ever practiced religious worship regularly at any place other than the current site?” If answered positively, the respondent filled in the name and site of the churches they have attended in the past.

In our sample, of the 117 Christians, 53 shifted from another church to their current one (45.30%), and the rest remained at one church. Of these 53 Christians, shifting from one Three-Self church to another Three-Self church was the most common pattern, reaching 39.62%. There was also 33.96% who shifted from a Three-Self church to a house church. It was rarest to shift from a house church to a Three-Self church, accounting for only 9.43%. It can be seen that in W, there is a greater inflow to house churches from Three-Self churches than the opposite direction, which confirms the fact that house churches are developing much faster than Three-Self churches.

4.3.2. Reason for the Flow of Urban Christians

In order to understand the reason why Christians shift from one church to another, we asked the question “What is the main reason why you shifted from your previous church to the current one?” Six choices were provided: “I like the preaching of the pastor”, “There is greater variety in the church activities”, “It is convenient to get here”, “I communicate with the pastor better”, “I have closer relationship with fellow Christians here”, and “Others”. Multiple selections were allowed. The results are shown in

Table 2.

As can be seen from

Table 2, reasons for shifting churches vary according to different categories. For those who shifted from one Three-Self church to another, the main reasons were transportation convenience (57.14%) and the preaching of pastors (38.10%). For those who shifted from house churches to Three-Self churches, the main reasons were the same, with 60% and 40%, respectively. However, for those who have shifted from Three-Self churches to house churches, the two most popular reasons were better communication with the pastor (50%) and greater variety in church activities (50%), while transportation convenience (44.44%) and relationship with fellow Christians (33.33%) were of less but still remarkable significance. As for those who shifted from one house church to another, transportation convenience was again at the top of their concerns (44.44%), while the preaching of the pastor and the variety of activities both occupied the secondary position in reasoning (33.33%).

In sum, in most cases, transportation convenience is the main attraction for Christians, followed by the quality of the preaching of the pastor. It is notable that, for Christians who shifted from Three-Self churches to house churches, the communication with pastors and the activities organized by the church were of greatest concern.

5. Further Discussion: Why Do Urban Christians Choose House Churches?

5.1. Three-Self Churches Are Unavailable Regarding Their Sites and Limited in Number

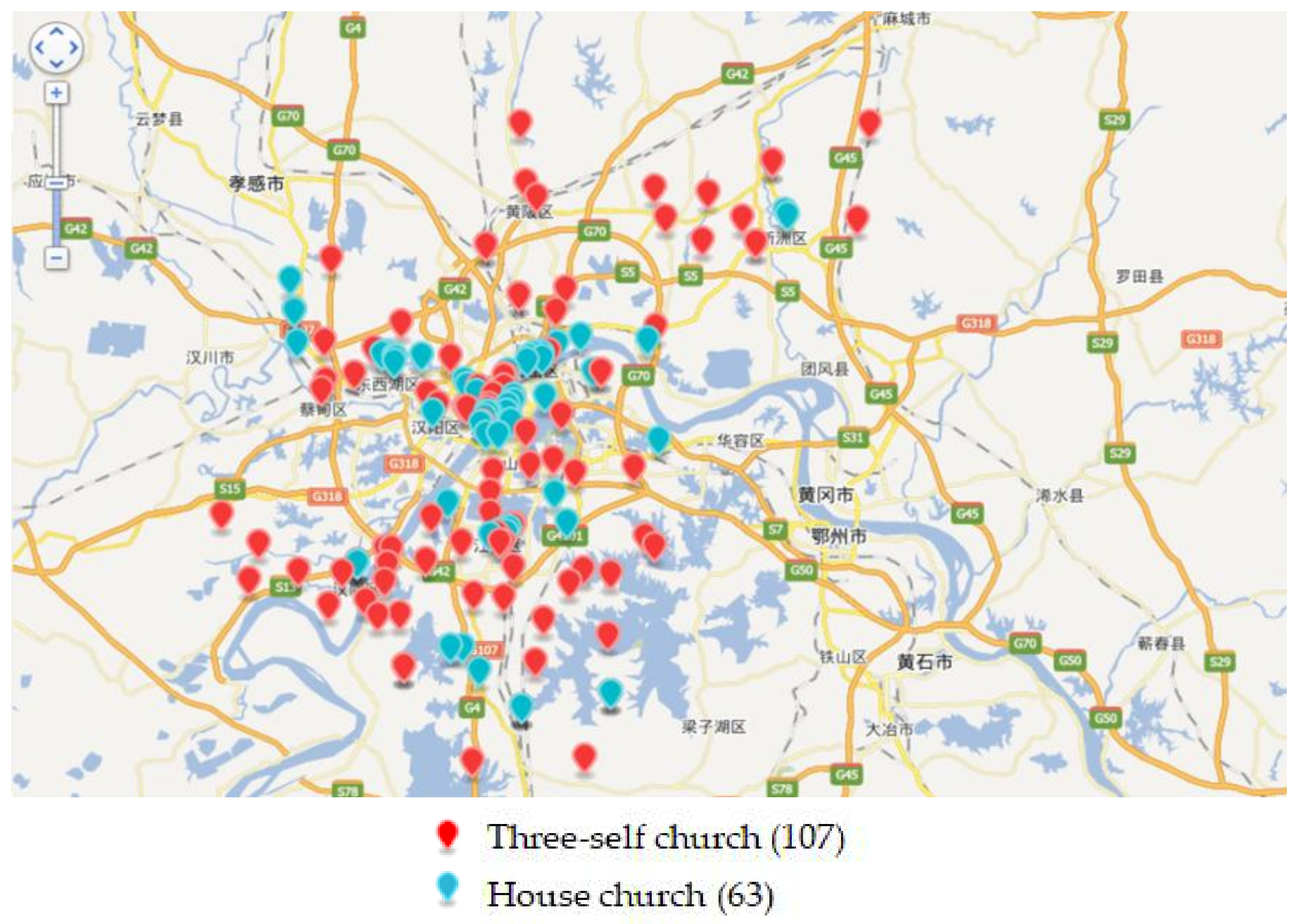

As shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, most Christians do not take into account whether or not a church is registered under the government as a “Three-Self church” when choosing a place to practice their religion. They tend to choose a church that is nearby. The sites of Three-Self churches and house churches in Wuhan city are marked on the map in

Figure 4.

Figure 4 shows that, in the densely populated city center, although the number of Three-Self churches is large, it still cannot satisfy the needs of Christians. Thus, many house churches are established in this area. In addition, many families live in suburban areas where there is a lack of Three-Self churches. They establish house churches in response to this void. Thus, it can be concluded that the number of Three-Self churches is insufficient and their distribution inconvenient, which causes some Christians to choose house churches instead.

Stark and Bainbridge (

1989)’s theory of religious economy may shed a light on such a phenomenon. This theory posits a religious market where “religious persons and organizations [are] interacting within a market framework of competing groups and ideologies”. Religious suppliers in the market offer various religious products to meet the demand of religious consumers. Because Three-Self churches are small in number and inconvenient in transportation, house churches that are more flexible and more satisfactory to these Christians’ demands are able to flourish.

To understand the scarcity of Three-Self churches, we spoke to a person in charge of the church, who explained that there are mainly two reasons behind this scarcity. Firstly, according to the current Regulations on Religious Affairs, all establishments of religious sites must apply to be registered with the State Bureau of Religious Affairs. Also, eligible churches need to fulfill a series of requirements. For example, all members of the clergy need to be qualified, there has to be a legal evidence of funds, and the church must also meet the requirements of the local government. Thus, the procedure of application is tedious and difficult. Secondly, the Chinese government’s attitude towards religion is ambiguous. Although China officially follows the principle of religious freedom and does not interfere in the religious lives of its citizens, the Chinese government is, in fact, sensitive to the penetration of foreign religions such as Christianity and their influence on the political and cultural climates in China. Thus, the government does not encourage the development of Christianity.

5.2. The Three-Self Church’s Ability to Serve Believers is Limited

As shown in

Table 2, to have more opportunity to communicate with the priest is the principle reason for believers to shift to house churches. Among those who formerly belonged to Three-Self churches, 50% stated that they chose to shift to house churches in order to have more communication with the priest. Oftentimes the Three-Self church cannot serve its believers to their satisfaction because of its large size and the limited resources of the clergy. House churches, on the other hand, are relatively small and can thus offer its believers plenty of opportunities to speak to a priest. Even in those house churches that are relatively large, the church can satisfy the needs of believers to a sufficient disagree by having believers elect respected members to serve the duty of a priest. For example, house church C in the city of Wuhan is a church that normally has 60–70 people showing up at each meeting. The number of believers fluctuates but never exceeds 100. However, it has a clergy of 11 people that is divided into four ranks: the chief priest, priests, preachers, and team leaders. They are well organized and have a clear division of labor. They work together to make sure that their meetings are successful. The church’s ability to serve the believers draws more and more people to participate in its meetings. Miss L, who attends this church on a regular basis, says that she had difficulty finding a chance to speak to the priest about her thoughts and confusions when she attended a Three-Self church because there were so many believers every time, but here at house church C, everyone has a chance to be heard and the priests are willing to care for the spiritual lives of the believers. Even if they do not have enough time to communicate during the course of collective activities, the priests and the believers can arrange small-scale meetings in their private time.

5.3. The Activities in Three-Self Churches Are Dull and Cannot Attract Believers

As shown in

Table 2, the diversity of activities is another important reason why believers shift to house churches. Fifty percent of believers shift to house churches for this reason. The main activities in the Three-Self church are reading scriptures and sermons. Many believers consider such activities old-fashioned and tedious. House churches, on the other hand, are small and can arrange the forms and contents of collective activities flexibly. They are thus more attractive to believers. Many believers also report that they are able to communicate better with other believers during the variety of activities held by house churches. This is also in accord with

Stark and Bainbridge (

1989)’s theory of religious economy. When the religious supplier is able to provide products of a greater variety and attractiveness, this supplier will profit the most in a competitive market.

The house church of M, for example, divides daily activities into two parts. Apart from Sunday worship, it also holds entertainment, training, and educational activities. Miss A, who has been in charge of the organization of church activities since 2013, says: “Our service here follows Christian traditions. The service includes singing the hymn, sharing thoughts, and reading scriptures. The theme of each worship is found in prayer and touching, and every believer has an opportunity to express his or her own embodiment of life. The form of our service is also very casual. We can share thoughts from Old Testament to New Testament chapter by chapter, or we can follow the chapters of the Bible. The activities of the church also include organizing small- and medium-sized Entrepreneur Forums, seminars on women’s family responsibilities, and so on. Generally, we have 100–150 participants, and several times we have attracted nearly 200 believers.” In recent years, she has also organized “concerts”, “marriage and family counseling”, “parent-child interactions”, and other activities. A summer camp held last year gave 120 children the chance to experience life abroad.

We also interviewed house church T, a church with its own book center that regularly buys various types of books. It also has a playroom for children and designated people to take care of young children when their parents participate in church activities. It holds table tennis and badminton competitions on a regular basis. Compared to Three-Self churches, house churches have forms of management that are much more flexible and activities that are more diversified. These conveniences enable easier communication among believers and attract more and more members.

5.4. Closer Ties Between Believers in House Churches Facilitate the Establishment of their own Social Network, Making Some Believers More Willing to Attend House Churches

As can be seen from

Table 2, 33.33% of the Christians who shifted from Three-Self churches to house churches think that there is a closer connection between Christians in house churches. To make more friends and establish new networks of social connections by participating in church activities is another reason why many believers choose to attend house churches. Compared to the traditional and bulky Three-Self churches, house churches are small in scale and flexible in form. The believers, through their participation in church activities, have the chance to interact with people from different places, professions, and social groups, thus gaining the opportunity to expand their social networks. Participants can meet people from potential business partners to like-minded friends. They are much more likely to make useful and meaningful social connections in house churches than in Three-Self churches, which are known for lacking communication among their members. Therefore, house churches in China can even be said to serve the function of a club.

The house church Q is an example of such a “club church”. Founded in 1998, Q is a house church located in a large commercial area in a district of the city of W. The founding members of the church were mainly residents of Taiwan, China. Apart from their common belief in Christianity, they also shared similar occupations as private entrepreneurs who were engaged in the production and sale of electronic products in W. In that sense, Q had characteristics of a guild in its founding stage. Today, the church is constantly expanding, drawing believers not only from Taiwan but also from Hong Kong, the United States, France, and the mainland. The head of the church said that Q was originally founded to facilitate communications and exchanges among Taiwanese people who work in the electronics industry in W. Church member L from Kowloon, Hong Kong, said that he came to Q mainly because he was involved in the business of electronic products and hoped to find useful business partners here. This kind of “club church” is a new form of urban house churches. Club churches usually have no definite sectarian background and no strict religious constraints. However, they have other restrictions on their members. For example, all members are required to come from similar professional backgrounds and may only join the church if they are introduced by acquaintances. Most of those from the business community and take up managerial positions. It is much less common for blue-collar employees to join these churches. Members will regularly donate a large amount of money to the church. In sum, these house churches have many characteristics of an “elite club”. Most of their members join to expand their own social networks.

5.5. Different Motivations: House Churches Have a Clearer Sense of Competition

Today in China, the pastors of Three-Self churches and the pastors of house churches have very different motivations for work. The Three-Self church is an official Christian organization with a professional clergy. Pastors have a fixed monthly wage income, which is borne by religious affairs from the state budget. As a result, priest of a Three-Self church has become an undisciplined profession with little competition. Once one becomes a pastor of the Three-Self church, one can obtain a fixed salary no matter how well one performs as a pastor. As a result, they generally lack motivation to run and manage the church to attract more believers. The priests of house churches, on the other hand, are willing to spend all of their time and energy to serve God and to run the church because of their devotion Christianity. They consider the development and expansion of the church to be a lifelong career. Moreover, they have no fixed salary, and the house churches they operate enjoy no financial support from the government. As a result, they must secure funding sources by attracting more donors.

We also found in the survey that Three-Self churches are not very motivated in the development of the church, while house churches, in sharp contrast, make every effort to draw in more believers. Some house churches send out pamphlets to passersby whenever there is a large flow of people to attract more believers. Miss N, whom we met during an interview, said that she found out about her house church and became a regular church-goer after receiving such a pamphlet. Other house churches encourage their own followers to persuade their friends and relatives to attend the church, and even offer material rewards to believers who introduce the most members to the church. This method is very effective. As our data shows, 48.68% of believers came to know about house churches through other believers.

6. Conclusions

Since the economic reform and opening up policy, the rapid development of Christianity in China and the remarkable expansion of house churches have attracted both nationwide and international attention. At the same time, with China’s ongoing urbanization, the inflow of rural population into the urban area also increases the demand of religious services in the cities. If Three-Self churches do not reform themselves in the aspects of geographical distribution, the number of churches, the capacity and variety of religious service, and the internal organization structure, they will have even less attraction for Christians and even less competitive advantage over house churches. The development of house churches in the urban areas also bring about new questions. How do we measure the influence of house churches in spreading Christianity in China? How should we understand the relationship between the government and new religious institutions? How will the competition between the Three-Self churches and house churches evolve? These are all questions to be explored by future research.

This study has its limitations. In reality, the attitude of local governments towards religious affairs can be expected to have an effect on the development of house churches and the choice of religious practice sites by Christians. Due to a lack of data, we were unable to compare different cities’ local policies. We expect to expand the investigated area and improve our research. Another research direction that might be fruitful is to study discrepancies in development of Christianity in urban and rural areas. It would also enrich the study immensely if we could investigate the variation of choice of religious practice sites of rural Christians as a comparison.