Abstract

Indic rites of purification aim to negate the law of karma by removing the residues of malignant past actions from their patrons. This principle is exemplified in the Kahika Mela, a rarely studied religious festival of the West Himalayan highlands (Himachal Pradesh, India), wherein a ritual specialist assumes karmic residues from large publics and then sacrificed to their presiding deity. British officials who had ‘discovered’ this purificatory rite at the turn of the twentieth century interpreted it as a variant of the universal ‘scapegoat’ rituals that were then being popularized by James Frazer and found it loosely connected to ancient Tantric practises. However, observing a recent performance of the ritual significantly complicated this view. This paper proposes a novel reading of the Kahika Mela through the prism of karmic transference. Tracing the path of karmas from participants to ritual specialist and beyond, it delineates the logic behind the rite, revealing that the culminating act of human sacrifice is, in fact, secondary to the mysterious force that impels its acceptance.

Keywords:

Himachal Pradesh; human sacrifice; karma; Khas; Kullu; Nar; ritual; scapegoat; shaktism; Tantra 1. Introduction

At some point in the mid-1930s, a British civil servant by the name of William Herbert Emerson (1881–1962) wrote an ethnography of the West Himalayan Khas ethnic majority on the basis of extensive first-hand experiences in the highlands of present day-Himachal Pradesh, India.1 In the ninth chapter, Emerson described a unique rite of purification that simulated what was once ‘most certainly’ an actual act of human sacrifice. Popularly known as the Kahika Mela, the ritual was part of a religious festival (mela) that saw a married couple of lowly status hosted by higher caste villagers, where they would perform various rites of purification over several days. The mela culminated in the offering of the male ritual specialist to the villager’s presiding deity and his resurrection shortly afterwards. The officiating couple would then resume its home, invariably located at a fair distance from the host community.

According to Emerson, the Kahika Mela comprised a local rendition of the ‘scapegoat’ rituals then being popularized by Sir James Frazer as a universal undercurrent of human religious behaviours across the globe (Frazer [1890] 1922, chps. 55–57).2 The handful of other commentators on the rite largely adopted this view while tweaking it to conform to their respective viewpoints. Thus, Mola Ram Thakur (1997, pp. 157–64) linked the Kahika Mela to Vedic-Puranic human sacrifices (narmedha yajna), while Arthur Horace Rose (1919) emphasized its ‘Tantric’ origins.3 While the ritual’s basic outline could indeed be construed to support these divergent hypotheses (Frazerian scapegoat, Brahmanical rite, devolved Tantrism), an examination of the Kahika Mela as performed in the Kullu Valley in August 2016 added significant new data that complicate these interpretations.4 This paper seeks to explicate the logic behind this rarely studied ritual by investigating its ritual procedures, the roles and social status of its officiates, and the meanings attributed to the human sacrifice that concludes it.

The multivalent registers of the Kahika Mela notwithstanding, it primary purpose of purification suggests it is best explained in light of the law of karma. Broadly formulated, the law of karma holds that actions (karmas) are morally evaluable, causative units that impact their agents’ futures insofar as they are believed to imprint the self with invisible residues that contain the seeds of future actions (Burley 2014). In other words, good actions breed positive outcomes while bad actions generate harmful outcomes; it is the latter that are the object of expiation in purification rituals. The notion that actions generate a polluting residue (pāpman) that disrupts a ‘correct’ (dharmic) cosmic, social, and personal order is traceable to Vedic sacrifices and remains central to Indic religions to date (Heesterman 1985, 1993; Witzel 2003). The methods devised to remove karmas—or rather the harmful potentialities that they carry and that are commonly glossed as ‘sin’ (pāp, doṣ)5—vary between sectarian traditions, reflecting the divergent cosmological assumptions that underlay them. Thus, yogi ascetics burn their karmas by generating heat through austerities (tapas) (Mallinson and Singleton 2017, p. 89), practitioners of devotional religion (bhakti) dissolve karmas through immersion with a chosen deity (Fuller [1992] 2004, pp. 155–81), while medieval Tantrikas advanced the initiates’ loss of weight (tulādīkṣā) as proof of their karmas’ absorption in the godhead (Sanderson 2001). This principle of ‘karmic transference’ pervades North Indian societies and manifests in the popular perception of the material exchanges entailed in social transactions as inherently dangerous (Raheja 1988).

Importantly, the spread of the malignant karmas that arise from the infringement of religiously framed social norms (pāp, doṣ) does not necessarily imply their transference from one vessel to another. Rather, removing such karmas requires an active effort that would decimate them at the source (Parry 1994, pp. 130–39). The procedures performed during the Kahika Mela exemplify this process to a fault. Subjecting these acts to close scrutiny is thus revealing of Khas perceptions of purity and pollution, and of the dynamic relations between gods and men. As the details of the mela reveal, the ritual specialists’ capacity for nullifying karmic residues connotes a distinction between the type of divine power (shakti) attributed to male and female entities, a distinction that holds the key to deciphering the purpose of the ritual procedures enacted in course of the mela.

After this introduction, an outline of the basic form of Khas expiatory rites and the social position of the Kahika Mela’s ritual specialists is presented as background for the detailed narrative of the performance observed in August 2016. The measures employed for constructing the ritual space and the cosmological assumptions that they reveal are examined next, and their contribution to the rite’s efficacy explained. A close account of the second phase of the mela follows with a focus on the device and method of expiation that renders karmas ‘perforated’ (chidra), demonstrating why this lengthy phase is also considered the main ‘work’ (kām) performed during the mela. The role of the female ritual specialist, although obscure in earlier accounts, is addressed in the final section, wherein her partner is offered in sacrifice to the host community’s presiding deity. An assessment of her actions in light of an early variant of the rite that is recorded in colonial sources concludes the analyses, suggesting the culminating act of human sacrifice is, in fact, secondary to the mysterious transformation that accompanies it, and that ultimately impels the host deity to accept the offering.

2. The Ritual and Its Specialists

The Kahika Mela falls within a broad range of purificatory rites involving scapegoats that have been recorded in the Kullu Valley since as early as the 1860s. The report of a British officer on a popular ‘expiatory ceremony’ among Kullu’s villagers delineates the general contours of these rites. According to the report, the ritual was ‘occasionally performed’ with the object of removing ‘greh’ (lit., ‘planet’) or ‘bad luck or evil influence said to be brooding over a hamlet’ (Lyall 1874, p. 155). The medium of the village deity would first decree the ritual be performed and a member of the community would then ‘volunteer’ to pass between its households with a creel on his back. Each family would deposit bits and pieces charged with malignant karmas into the creel, which the volunteer would then discharge at the bank of a river or a stream. A goat sacrifice would follow with half of the offering being consumed in a communal feast and the remainder granted to the volunteer as pay. The underlying law of karmic transference is evident: the volunteer risks exposure to the malevolent substances that he is to distance from the community and is rewarded with food in return.

While the Kahika Mela follows the basic contours of this unspecified rite (including irregular performance), it differs from the latter in that its executors must be external to the community being cleansed. This is no mean exception, for Khas society between Kullu and Garwhal is almost uniformly organized into socio-territorial units under the authority of deities that act as kings (Emerson n.d.; Sutherland 2006; Sax 2006; Moran, forthcoming). These god-kings, whose affairs are managed by the dominant lineages of the community (devta log), embody the collective will of their followers (deule) through a series of local institutions. Communal decisions are enacted and directed by the deity through an inner circle of officiates that includes a ‘chief administrator’ (kārdar) who is usually also the leader of the community, the medium (gur) who speaks for the deity, and the priests (pujaris) who see to its ritual needs. As the medium of Larain Mahadev, the god-king who commissioned the Kahika Mela under examination, explained, this inner circle constitutes a ‘family’ (parivar) insofar as the executive officer (kārdar) must take heed of the deity’s wishes (announced through its medium) and vice versa in all communal affairs (Dasu Ram, personal communication, 16 August 2016). Thus, if the medium decrees a Kahika Mela, its arrangement is hammered out in consultation with the kārdar and in agreement with the devta log in council. That the Kahika Mela relies on an outsider to this ‘family’ for its execution is indicative of the considerable stakes involved, the ritual specialists’ provenance from beyond the god-king’s territorial (har) and social (deulu) jurisdictions qualifying his service as sacrificial victim.

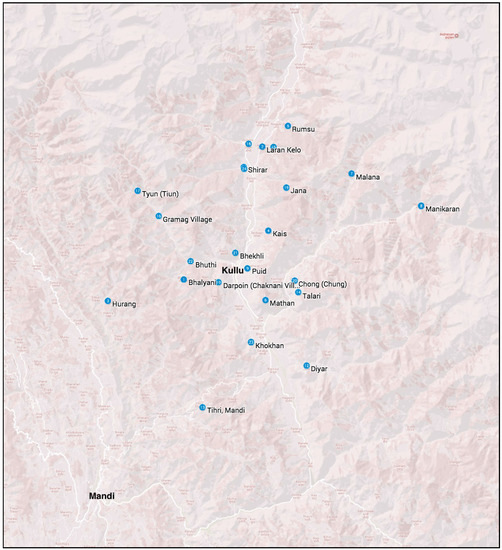

The ritual specialists who preside over Kahika ceremonies are (most often) a married couple of the Naṛ community (also spelt Nauṛ or Nauḍ, henceforth ‘Nar’), a group that occupies a unique position in the mainstay of Khas ‘caste society’. Spread between their two major settlements in easterly Manikaran (Kullu) and westerly Jogindernagar (Mandi), the Nars seem to have originated in the Tibetan cultural zone of Spiti beyond the Pin-Parbati Pass. While concrete evidence for this origin is lacking, their mythic descent from the marriage of a demi-god to a ‘Bhotanti woman’, which in Kullu implies Spiti, would strengthen this hypothesis (Lyall 1874, pp. 149–50). The Nars’ role as redeemers (udhārak) is hinted at in another origin myth from the westerly region of Mandi. The Nars, so goes the tale, originally served as musicians to Indra, the king of the gods, and were renowned for their purificatory abilities. Having acquiesced to heal a village god smitten with leprosy, the Nars descended to earth to perform their magic. However, as soon as they had completed their task, the villagers smeared them with the taboo substance of oil. Thus polluted, the heavenly healers were forced to remain on earth, where they periodically purify gods and men to date ((Thakur 1997, pp. 163–64); for a preliminary list of sites where the Kahika Mela is currently held, see Figure 1). The community’s mythical role as entertainers is evident in Kahikas, wherein the Nars are key merrymakers, taking jibes at their hosts, and leading the processions (hulki) of revellers in dance during key moments of the ritual ((Emerson n.d.; Thakur 1997, p. 163), also corroborated by fieldwork).6

Figure 1.

Map of places where Kahika is celebrated (central Himachal Pradesh, India).

The government of India classifies the Nars as an Other Backwards Class (OBC), which places them in the gray area between the ritually pure ‘caste Hindu’ majority and its so-called ‘untouchable’ (achut or dalit, ‘oppressed’) inferiors.7 Colonial sources describe them as a subgroup of the ‘unclean’ caste of Dagis (along with Doms and Kolis), who are linked to Punjabi Chamals, the supposed descendants of Ancient India’s Chandalas (Rose 1919, vol. 2, pp. 151–52, 217–19, vol. 3, pp. 157–58). When not officiating at Kahikas or tilling their fields, the Nars serve as koridārs or ‘courtyard people’ to Khas families, that is, as subservient service providers whose presence is restricted to the open courts of their patrons (or to the lower rooms of their houses, but never near the hearth). In the event of a death among their patrons, the Nars were to provide ‘fuel for the funeral pile and funeral procession, and do other services, in return for […] food and the “kiriā” of funeral perquisites’ (Lyall 1874, p. 151). In this respect, the Nars comprise a local version of Northern India’s funerary priests, the ‘Acharj Brahmins’ or ‘mahabrahmans’.8 This semblance is particularly striking in the case of members of the community who served as priests (purohits) to kings, chiefs, and ‘wealthy people’ (Rose 1919, vol. 3, pp. 133–34). The pret palu of Mandi, an erstwhile kingdom bordering southern Kullu, are a case in point.

Upon the death of a raja, a low class Brahmin known as the ‘pret palu’ (‘soul/spirit sustainer’) was summoned to act as a surrogate for the departed ruler. The pret palu was to take residence in the palace, don the late ruler’s clothes, and ‘in some places [was] even addressed as raja’, an identification contingent on his consumption of rice balls containing powder grated off the dead ruler’s skull. At the end of his sojourn (usually lasting a whole year), the pret palu was laden with gifts and indefinitely banished from the kingdom (Emerson [1920] 1933).9 The similarities with the ‘katto Brahmins’ that tended to rulers of Nepal’s Shah dynasty (1559–2008) are readily apparent. As in Mandi, the death of Shah rulers occasioned the summoning of a ‘scapegoat’ who would assume the late ruler’s corporeal and ethereal residual substances and then leave the kingdom indefinitely so as to ensure the successor’s successful transition to power (Kropf 2002; Lecomte-Tilouine 2005; Mocko 2015; Witzel 1987). The function of the pret palu of Mandi and the ‘katto Brahmin’ of Nepal—so named after the kāṭṭo khuvāune meal containing powder from the dead king’s skull—is thus identical, namely, to distance karmic residues from the state by incorporating them into their body and then leaving the state forever. The implications for the Nars officiating at the Kahika Mela are clear: as a popular version of the pret palu, their duty is to absorb and remove the karmic residue of the community that commissioned their services. However, unlike the latter, the karmic residue that they remove during Kahikas is directed at the god-king itself (through the offering of the male ritual specialist) rather than away from its territory! To make sense of this seeming inversion in the flow of karmas, it is necessary to take a closer look at the details of the Kahika Mela that was held in Laran Kelo on the first day of the rainy month of Bhadon.

3. The Kahika Mela in Laran Kelo: Constructing the Ritual Space

The performance observed on site followed the tripartite structure of Kahika Melas outlined by Thakur (1997): the creation of a ritual space (kahika kharerna), the performance of expiatory rites by the Nar officiates (chidra yajna), and the offering of the male ritual specialist in sacrifice (narbali). During the first stage, the hosts erected a canopy called ‘kahika’10 adjacent to the god-king’s temple, under which the Nars constructed the ritual space. The second stage saw the karmas of the assembled ‘perforated’ or ‘pierced’ (chidra) by the male ritual specialist, who then absorbed them into his body; this was the main ‘work’ (kām) of the Kahika. The mela concluded with the latter’s ‘sacrifice’ and ‘resurrection’ by the assembled deities, after which the canopy was dismantled and the Nars resumed their home in the upper reaches of the valley, well beyond the limits of the host community. While the sources at hand claim the Kahika Mela terminates at this stage, enquiries in situ revealed it is only deemed to be completed a week later, when the host deity is carried to a waterway (the Beas-Parvati sangam), bathed, returned to the village, and reinstalled as sovereign (Dasu Ram, personal communication, 16 August 2016). The rationale behind this reading is evident when viewed through the prism of the law of karma: having accepted the sins of its followers, the deity washes them downstream so that it may be re-installed (pratiṣṭhā) as god-king.

The centrality of karmic transference to Khas society and its indication of the actual endpoint of the Kahika Mela are instructive of the ritual’s aims. By focusing on the removal of karmas as observed in the performance in Laran Kelo, the motives for the Nars’ actions and their contribution to communal expiation become evident from the very beginning of the ritual. Thus, after the canopy was erected (but before its supporting pegs were nailed into the ground), the Nar and the Naran used flour from the host deity’s storehouse (bhandar) to draw a rudimentary square yantra whose median and diagonal lines intersected at its centre. The yantra was empowered with seeds and pulses from the storehouse (Figure 2) and an additional chart of the nine planets (navagreha) was drawn to its south in the direction of the Lord of Death (Yama). An effigy of cow dung was placed next to the supplementary yantra. While the image was said to be Ganesh, the Lord of New Beginnings, its location in the ritual grounds suggest it may also serve to allow deceased relatives to partake in the process of purification (more on this below). The Nars, elevated on a sack of flour that substituted for a divine throne (āsana), then produced the ḍāḍh, a ‘drum-shaped piece of wood about two feet high, which for some obscure reason is regarded as essential to the proper performance of the rites’ (Emerson n.d., fo. 405).11 While Emerson recognized the ḍāḍh is crucial to the rite, the fact that he never witnessed a Kahika in person seems to have prevented his realizing its full significance. The careful consecration and subsequent use of this device made it palpably clear that this was the most important object in the ritual.

Figure 2.

Empowering the yantra (Kahika Kharerna).

Having secreted the ḍāḍh from a plastic bag, the Nar wrapped it in white cloth and placed it at the centre of the ritual space above the square yantra. He then drew a replica of the base yantra on top of the device. Locked between these parallel, ritually empowered representations of the universe, the otherwise innocuous device became a ‘cosmic trap’, an extra dimensional locus for containing the malignant karmic residues of the public, and that could only be operated by the Nar.12 With the ritual space set up, the Nar summoned deities into his body through gestures and mantras as per standard Tantric practise (nyāsa puja). As with the seeds and flour that empowered the ritual space, the Nar held daggers (katars) obtained from the god-king’s treasury during the puja, suggesting his powers were at least partly derived from the host deity.13 The consecration complete, the Nar resumed his throne and the supporting pegs were hammered into the ground. The cleansing of sin could begin. (see Video S1: https://vimeo.com/229028753. Preparation of the ritual grounds and expiation by touch. Copyrighted footage from the documentary Chidra (2018)).

4. Purification by Perforation: Chidra Yajna

Shortly after the ritual space had been prepared, the Nars performed the first of seven chidra yajnas, the communal rites of purification for which the mela is celebrated.14 As Daniela Berti observes, chidra (lit., ‘perforated’, also ‘pierced’ or ‘cut’) is a ritual procedure that is also performed by mediums. Aimed at negating the effects of ritual transgressions (doṣ) that have been punished by gods (devta), Tantric sorcerers (ṭāṇag), or ghosts (bhut), these ‘rituals of cutting’ restore social harmony in much the same way as a Middle Eastern sulh settles longstanding disputes between extended families. The procedure is simple: a cord is tied to the leg of a sacrificial animal (usually a lamb), with the concerned parties holding on to its ends; the medium pronounces ‘various sentences which announce the end of the problem in question’, and the parties exclaim ‘chidra’ at the end of each sentence as they cast ‘grains of barley, corn and oats onto the animal’s leg’; when the list of grievances is completed, the medium cuts the cord and the doṣ is considered removed (Berti 2012, pp. 159–61).15 This version of the procedure exhibits the basic components required for performing chidra: a ritual specialist, an offering, and the presence of the clients seeking absolution from the baneful influences of ritual transgressions/social falling-outs.

The chidras performed during the Kahika were similarly crafted, but with variations that are telling of the rite’s significantly wider scope and potency. First, instead of a medium, it is the male Nar who performs the chidra with the mediums of the host god-king and those of its divine guests at his feet. The grievances listed were numerous and tailored to those in attendance, whether human or other. Thus, alongside the pronouncement of (purposeful or inadvertent) transgressions made against local deities and their retainers (primarily witches and demons, dain-rakh), specific incidents that took place since the preceding Kahika was held were enumerated; these included curses (shapni) cast by former mediums on new ones, by kardars against others, the affronts of priests who had been insufficiently paid, quarrels over bookkeeping, scuffles in temples, insults hurled at persons identified by name, and so forth. Each of these rounds concluded with a temporal sealing of the absolution by repenting for misdeeds against the rising sun, the setting sun, the twelve new moons, and the twelve full moons. As with the rite administered by mediums, the assembled exclaimed the faults enumerated to be ‘perforated’ (chidra) at the end of each sentence (see Video S2: https://vimeo.com/229034073. The last round of chidra yajna. The chariots (raths) of the seven god-kings invited to the Kahika Mela assemble for the rite, the long haired-mediums dressed in white sit below the Nars, while the public surrounds the sacred space in participation. Copyrighted footage from the documentary Chidra (2018)).

Another important divergence from the mediums’ chidras is the absence of the cord connecting the aggrieved parties. The breadth of transgressions redressed during the Kahika, which includes a host of imperceptible entities (demons, gods, etc.), would suggest the cord is redundant in this context. At the same time, the notion that all the parties implicated in the faults being redressed needed to be in attendance for the rite to succeed was maintained. In the case of gods, goddesses, and their supernatural associates, this was achieved by the Nar’s noting their presence in every round of chidra.16 In the case of deceased persons with unfinished business in the world of the living, expiation was provided through the effigy that had been constructed and placed at the southern end of the ritual space at the beginning of the Kahika. Finally, in lieu of a sacrificial animal, the participants cast their grains at the cosmic trap (ḍāḍh) at the centre of the ritual space.17 The faults (pāp, doṣ) or residual karmas that were the object of purification were thus transferred to a dimension that was both visible and contained, it being common to find participants bowing in reverence before the ḍāḍh in the course of the ‘private’ chidra yajnas performed under the canopy between public rounds (Figure 3). For participants and visitors to the fair, the ḍāḍh was a constant reminder of the risks underlying the Kahika; progressively overladen with additional layers of grains, pulses, the cosmic receptacle and the ritual space around it became a palpable manifestation of the dangerous substances that participants had shed on the site.

Figure 3.

Private Chidra Yajna.

Throughout the numerous rounds of chidra yajnas, the Nar kept his left hand fingers on the ḍāḍh while casting grains on its surface with his right hand (Figure 4). By maintaining contact with the object of the participants’ malignant karmas—or rather, the actions that bound them to aggrieved parties and their potentially perilous outcomes—the ritual specialist accrued the harmful, invisible substances of numerous communities in the course of three, heavily charged days. By the end of the seventh and final round of chidra (Figure 5), his body has absorbed a critical mass that, as the law of karma dictates, was to be removed elsewhere in order for the rite to succeed. It was then that the infamous association of the Kahika Mela with human sacrifices came into play.

Figure 4.

Chidra Yajna, casting grains on the ḍāḍh. Note the ritual specialist’s physical contact with the ‘cosmic trap’.

Figure 5.

Final Round of Chidra Yajna. The mediums sit below the Nar, the deities chariots (raths) and followers in the background.

5. Disposing of Karmas: The Stakes behind the Human Sacrifice

The sacrifice of the male ritual specialist (narbali) is the focal point of the Kahika Mela. While the details of its performance vary between locales, the format is largely the same: the Nar is ‘killed’ as an offering to the host deity and after a few minutes brought back to life through the divine energy of the god-king and its guest deities. That there is more to this part of the ritual than meets the eye is evident given the central, unwritten law (niyam) of the Kahika that was mentioned by nearly every person questioned. According to this law, if the Nar fails to revive, his wife receives the entirety of the assembled deities’ lands, riches, and images. On a strictly material level, this law provides a strong incentive for the gods to succeed in resuscitating their victim, since the Nar’s death would spell their extinction. However, the delineated path of karmas suggests there is more at stake in this moment than a seemingly contrived display of divine power. By this stage of the Kahika Mela, the Nar is so heavily laden with (invisible) toxic residues that his death is tantamount to a karmic apocalypse. The understanding that the gods would lose their powers in such an event is thus not simply a matter of convention, but a reflection of the disastrous consequences that would ensue should the malignant karmas accrued on the Nar fail to reach their destination and contaminate the ritual site.

As with the misperceived significance of the cosmic trap (ḍāḍh) for explaining chidra yajnas, observing the rite on site yielded crucial data that filled the gaps in earlier studies. The killing of the Nar in Laran Kelo took place after three days of communal expiation ceremonies (chidra yajnas). The gods and the public, led by the dancing Naran (Figure 6), assembled at a clearing above the fairground to the beat of the drums, forming a circle around the host deity’s chief administrator (kardar) and the Nar, who stood facing each other at a short distance. Armed with a short bow and even shorter, magically charged arrows (Figure 7), the kardar shot the Nar in the stomach and his victim summarily fell back into the arms of the god-king’s servants.18 Wrapped in white cloth, the erstwhile redeemer was carried on the arms of the hosts’ leaders (devta log) to the ritual space adjacent to the temple to the cries of ‘Die! Die!’ (maut ho! maut ho!), where his body was laid under the canopy. The Naran, who had till then played complacent partner to her charismatic husband, stood above her unconscious (mūrchit) husband’s head. Surrounded by gods, mediums, and a mass of huddling spectators, she performed the rite of chidra over his cloth draped-‘corpse’, casting the grains over his body. No sooner was she done than the god-kings began channelling their energy (shakti) to revive the Nar. The divine chariots (rath) shook violently, the mediums grew possessed, and ‘laymen’ receptive to the power began jumping, heaving, and rocking back and forth in possession. Within minutes, the Nar had revived, the canopy was dismantled, and the gifts that had been tossed over it during three days of festivities set free and awarded to the ritual specialists.

Figure 6.

The Naran leading in dance towards the site of the killing (Narbali).

Figure 7.

The kardar prepares to sacrifice (Narbali).

If, as Michael Oppitz claims (Oppitz 1993), the brief moment of sacrifice is the most important part of sacrificial rituals, then its analysis should yield important insights into the premises that mandate its execution. The fact the Nar’s revival is not perceived to be guaranteed suggests that there is, as one participant put it, an ‘actual process’ being played out in the closing act of the Kahika Mela. Again, the law of karma is key. The act of sacrifice transfers the offering (in this case, the accrued faults of several communities) from the Nar’s body to the host deity. However, simply ‘killing’ the victim is not enough, as it is up to the Naran to deliver the offering by performing the chidra yajna over her husband.19 This pits the Naran against the god-king, who can either accept or reject the offering. The Nar’s revival signifies an acceptance of the offering and, by extension, of the pollution handled in the course of the Kahika. The drama surrounding the human sacrifice is thus less to do with whether the Nar will live or die, but with the hosting god-king’s capacity to absorb the karmas that his offering had accrued as surrogate for the ritual participants’ faults.

This reading of the rite has profound implications for understanding the relationship between gods and men, and for the scope of human agency in dealings with the order of divinities. As far as the handling of karmic residue is concerned, the offering (Nar) and its recipient (god-king) are on an equal footing, their success in handling/absorbing pollution rendering them acutely susceptible to death. As the unwritten law of the Kahika makes clear, the god-king’s failure to absorb these karmas spells his doom, dictating a sum-zero game in which the ritual, although theoretically prone to collapse, is almost always successful.20 If the Nar and the god-king share a capacity for absorbing or carrying the hazardous substances that have been wrested from the community during the chidra yajnas, the Naran’s sustained purity in face of these materials places her at the apex of the theocratic hierarchy instated during the mela. Thus, while her husband toils to affect the flow of karmas from the public to his body via the cosmic trap, the Naran only fully manifests her power in the final moment of sacrifice: as the performer of chidra, she effectively forces the god-king to accept the poisonous gift that is her spouse, since refusal would result in its annihilation.21

The immunity of the Naran to karmas is particularly striking in light of the sponge-like capacities of the Nar and the god-king, and is ultimately to do with the characterisation of divine female energy (shakti) among the Khas. The nature of this energy was evinced in several key moments of the Kahika Mela (mostly surrounding public rites of chidra), when the Naran passed between participants and gently hit them on the back with her hands clasped (see Video S1). Apart from transgressing the normative convention of separation between the sexes and the caste Hindus’ aversion to physical contact with ritually inferior peers, the fact that the Naran’s pats were repaid in cash indicates that they did affect some sort of change. The Nars’ ritual role as purifiers suggests her acts were indeed interpreted as achieving this effect. However, unlike her spouse, who employed a ritually empowered receptacle (ḍāḍh) to capture malignant karmas, the Naran’s strokes seem to have sufficed to affect expiation. The difference between the Nar and the Naran’s modes of expiation suggests the latter was endowed with an innate purity (śuddhi) that alleviates karmic residues by touch. Thus, while the Nar resorted to elaborate procedures and devices to affect the removal of karmas, his spouse was conspicuously lacking in such efforts.

The incongruence between the ritual specialists’ respective methods of expiation begs the question of identifying their sources of power, and that of the Naran in particular. A plausible explanation may be found in a variant of the Kahika Mela that was current in the late nineteenth century-‘hermit village’ of Malana.22 Tucked in the inner recesses of the Kullu Valley at a couple of days’ marching distance from Laran Kelo, the residents of Malana entertained ‘a peculiar custom’ in connection with their god-king, Jamlu,

Agreeing with the Kahika Mela in name, season and irregularity of performance, and in the caste identity of its ritual specialist, the Malana ‘kaika’ is clearly linked to the nowadays-common variants that have Nar couples act as officiates. Since this is the earliest account of a Kahika available,25 it is probable that the ritual celebrated today is but an elaboration of the latter. While a precise delineation of the ritual’s practical evolution would require further research, if we accept that the Malana variant does indeed represent an earlier stage of the rite then the consecration of the ritual space, the transference of karmas, and the human sacrifice that capped the Kahika in Laran Kelo would, on the elusive level of divinity, amount to little more than an extended prelude to a wedding between the god-king Larain Mahadev and the Naran. The Naran, for her part, would have thus been transformed, for the few precious minutes during which her husband laid ‘dead’, into a veritable virgin goddess.26[n]amely, the dedication to him of a handmaid (called Sita23), taken from a family of the Nar caste resident at Manikaran. The handmaid is presented as a husband [sic] to the god at a festival (kaika), which occurs at irregular intervals of several years, on the first of Bhádron. On dedication to the god, the girl, who is four or five years old, receives a gift of a complete set of valuable ornaments from the shrine. She remains in her parents’ house, getting clothes and ornaments at intervals. If she goes to Malána she is fed. She does nothing in the way of worship of Jamlu. When she is 15 or 16 years old a new handmaiden is appointed in her place.24(Rose 1919, vol. 3, p. 265)

***

This study began with a somewhat naïve attempt to explain a mysterious, seldom-examined ritual whose origins seemed to lie in archaic human sacrifices. Despite subscribing to the Frazerian scapegoat paradigm suggested by Emerson, the Kahika Mela displayed a variety of features that defied its location within a single religious tradition. Neither the Vedic-Puranic variant proposed by Thakur nor the devolved Tantrism advanced by Rose, the autochthonous festival aggregated various ritual elements that were impossible to isolate on the basis of the partial evidence available in earlier works.27 If the treacherous cycle of recursive reasoning entailed in identifying the particular sub-currents informing the rite was to be avoided, the Kahika Mela had to be examined on site.

The data collected during fieldwork filled the lacunae of earlier studies, prompting a reorientation of research towards the mela’s fundamental aim of purification and, by extension, to the principle of karmic transference. The inner logic of the ritual thus delineated proved, perhaps unsurprisingly, congruent with regional patterns of ‘place-making’ in oracular consultations.28 The removal of karmic residue by way of perforation, unanimously conceded as the main ‘work’ of the Kahika Mela, is of singular importance in this regard, the chidra yajnas enacting karmic transference being consistent with belief systems among both the Khas and their neighbours.29 The focus on ritual actions and on the Naran’s performance of chidra over her ‘dead’ husband’s body in particular were found crucial for explaining the act of sacrifice. Following the path of karmic residue from the public to the Nar and on to the hosting god-king (and thence to the confluence of rivers, away from the hills) also resolved the enigmatic role of the Naran in studies of this rite to date. Applying this action oriented-approach to the entirety of the mela yielded further, less evident insights about the gendered perception of divine power that subvert common wisdom. Instead of a celebration of the power of the gods (Kullu Kesari 2016), the spectacle of death and resurrection hinged on the female ritual specialist’s emergence as a virgin goddess.30 By ‘forcing’ the god-king to accept the karmic residues accrued by her husband, the Naran, as goddess, brought the labours of her partner to fruition, his revival evincing her success.

Apart from its correlation with Indic and Tibetan rites of purification, the delineation of karmic flow in the far reaches of the Hindu Himalaya is suggestive of the ideas underlying more complex forms of Tantric societies. The periodic emanation of the Naran’s virginal power in the Kahika Mela thus echoes the exceedingly more elaborate cult of Kumari in Nepal, implying a grassroots solution to the perennial problem of reappointing premenstrual girls as goddesses through ritual means. Similarly, the insinuated wedding setting of the ritual under a canopy could be read as proof that the Naran is never actually widowed insofar as she is destined to serve as the god-king’s purifying partner (as per the Malana variant of the Kahika). While further research is required before such hypotheses can be corroborated or refuted, the bottom-up investigation of the ritual proposed herein has made at least one thing palpably clear: in the West Himalayan Khas context, redemption is not the heavenly gift of divine grace, but the outcome of laborious efforts enacted by real life-ritual specialists, whose poisonous offering can only be rejected at the price of death.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/9/3/78/s1, Video S1: Preparation of the ritual grounds and expiation by touch. Copyrighted footage from the documentary Chidra (2018), Video S2: The chariots (raths) of the seven god-kings invited to the Kahika Mela assemble for the rite, the long haired-mediums dressed in white sit below the Nars, while the public surrounds the sacred space in participation. Copyrighted footage from the documentary Chidra (2018).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Axelby, Richard. 2015. Hermit Village or Zomian republic? An update on the political socio-economy of a remote Himalayan community. European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 46: 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Berti, Daniela. 2012. Ritual Faults, Sins, and Legal Offences. A Discussion about Two Patterns of Justice in Contemporary India. In Sins and Sinners: Perspectives from Asian Religions. Edited by Phyllis Granoff and Koichi Shinohara. Leiden and London: Brill, pp. 153–72. [Google Scholar]

- Burley, Mikel. 2014. Karma, Morality, and Evil. Philosophy Compass 9: 415–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaoul, Alejandro. 2008. Chöd Practise in the Bön Tradition. Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, Amit. 2013. Making a ‘Dead’ Man Alive. Channel 7 News Report. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2jC-FQokGxY (accessed on 4 March 2018).

- Dachille, Rae Erin. 2017. Piercing to the Pith of the Body: The Evolution of Body Mandala and Tantric Corporeality in Tibet. Religions 8: 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotson, Brandon. 2015. The Call of the Cuckoo to the Thin Sheep of Spring: Healing and Fortune in Old Tibetan Dice Divination Texts. In Tibetan and Himalayan Healing: An Anthology for Anthony Aris. Edited by Charles Ramble and Ulrike Roesler. Kathmandu: Vajra Publications, pp. 148–60. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Herbert William. 1933. Death Ceremonies of the Hill Rajas. In History of the Panjab Hill States. Edited by Jean-Philippe Vogel and John Hutchison. Lahore: Superintendent, Government Printing, Punjab, Appendix VII. pp. viii–ix. First published 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Herbert William. 2012. Gazetteer of the Mandi State 1920. Delhi: B.R. Publishing Corporation. First published 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Herbert William. n.d. A Study of Himalayan Religion and Folklore. London: British Library, Asian and African Collections.

- Frazer, James George. 1922. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. First published 1890. Available online: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Golden_Bough (accessed on 4 March 2018).

- Fuller, Christopher John. 2004. The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India. Princeton: Princeton University Press. First published 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Guidoni, Rachel. 1998. “L’ancienne cérémonie d’État du Glud.’gong rgyal.po à Lhasa”, Mémoire de DREA de Tibétain. Paris: INALCO. [Google Scholar]

- Handelman, Don, and David Shulman. 1997. God Inside Out: Śiva’s Game of Dice. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heesterman, Johannes Cornelius. 1985. The Inner Conflict of Tradition: Essays in Indian Ritual, Kinship, and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heesterman, Johannes Cornelius. 1993. The Broken World of Sacrifice: An Essay in Ancient Indian Ritual. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison, John, and Jean-Philippe Vogel, eds. 1933. History of the Panjab Hill States. 2 vols. Lahore: Superintendent, Government Printing, Punjab. [Google Scholar]

- Janowitz, Naomi. 2011. Inventing the Scapegoat: Theories of Sacrifice and Ritual. Journal of Ritual Studies 25: 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jassal, Aftab S. 2017. Making God Present: Place-Making and Ritual Healing in North India. International Journal of Hindu Studies 21: 141–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropf, Marianna. 2002. Katto Khuvaune: Two Brahmins for Nepal’s Departed Kings. European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 23: 56–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kullu Kesari. 2016. Nar Killed and Revived by Divine Power in Laran Kelo. Kullu Kesaru, August 19. [Google Scholar]

- Lecomte-Tilouine, M. 2005. The Transgressive Nature of Kingship in Nepal. In The Character of Kingship. Edited by Declan Quigley. New York: Berg, pp. 101–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lyall, James B. 1874. Report of the Land Revenue Settlement of the Kangra District, Punjab, 1865–1872. Lahore: Central Jail Press. [Google Scholar]

- Translated and Edited by James Mallinson, and Mark Singleton. 2017, The Roots of Yoga. Milton Keynes: Penguin.

- Mocko, Anne Taylor. 2015. Demoting Vishnu: Ritual, Politics, and the Unmaking of Nepal’s Monarchy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, Arik. forthcoming. God, King, and Subject. Journal of Asian Studies.

- Oppitz, Michael. 1993. On Sacrifice. In Nepal, Past and Present, Proceedings of the Franco-German Conference, Arc-et-Senans, June 1990. Edited by Gérard Toffin. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers, pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, Jonathan. 1994. Death in Banaras. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raheja, Gloria Goodwin. 1988. The Poison in the Gift: Ritual, Prestation, and the Dominant Caste in a North Indian Village. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Horace Arthur. 1919. A Glossary of the Tribes and Castes of the Punjab and the Northwestern Frontier. Lahore: “Civil and Military Gazette” Press, vols. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, Alexis. 2001. History through Textual Criticism in the Study of Śaivism, the Pañcarātra and the Buddhist Yoginītantras. In Les Sources et le temps. Sources and Time: A Colloquium. Edited by François Grimal. Publications du département d’Indologie 91. Pondicherry: IFP/EFEO, pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sax, William S. 2006. Divine Kingship in the Western Himalayas. European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 29–30: 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, Peter. 2006. T(r)opologies of Rule (Raj): Ritual Sovereignty and Theistic Subjection. European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 29–30: 82–119. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Tai-Yong. 2004. Emerson, Sir Herbert William. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/67177 (accessed on 23 July 2017).

- Tāntrikābhidhānakośa II. 2004. Tāntrikābhidhānakośa II. Dictionnaire des termes techniques de la littérature hindoue tantrique. A Dictionary of Technical Terms from Hindu Tantric Literature. Wörterbuch zur Terminologie hinduistischer Tantren. sous la direction de H. Brunner, G. Oberhammer et A. Padoux. Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-historische Klasse, Sitzungsberichte, 714. Band. Beiträge zur Kultur- und Geistesgeschichte Asiens 44. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, Molu Ram. 1997. Myths, Rituals and Beliefs in Himachal Pradesh. New Delhi: Indus Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, Hugh B. 1999. The Extreme Orient: The Construction of ‘Tantrism’ as a Category in the Orientalist Imagination. Religion 29: 123–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzel, Michael. 1987. The coronation rituals of Nepal, with special reference to the coronation of King Birendra in 1975. In Heritage of the Kathmandu Valley. Proceedings of an International Conference in Lübeck, June 1985, Lübeck, Germany. Edited by Niels Gutschow and Axel Michaels. Sankt Augustin: VHG Wissenschaftsverlag, pp. 418–67. [Google Scholar]

- Witzel, Michael. 2003. Vedas and Upanisads. In The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Edited by Gavin Flood. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 68–101. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Emerson served as superintendent and de facto raja of Mandi State in the 1910s and frequently visited the hills from his postings in the Punjab during the 1920s. Although it was never published, substantial segments of the ethnography came to inform The Gazetteer of the Mandi State (Emerson [1920] 2012), while the original text is preserved at the British Library, Oriental and India Office Collections (hereafter OIOC), Mss Eur E321. For a short biography of Emerson, see Tan (2004). |

| 2 | On the genealogy of the ‘scapegoat’ category and its complications, see Janowitz (2011). For an important study of a Tibetan variant, see Guidoni (1998). Since Kahikas are held at the seam of Indic and Tibetan cultural zones, comparisons with the latter are often fruitful, more on which below. |

| 3 | The works of Emerson, Thakur, and Rose are the main sources discussing the Kahika available to date. On the British legacy of equating non-Brahminical practises with ‘Tantra’, see Urban (1999). |

| 4 | My thanks to Nadav Harel for video and stills documentation of the ritual. |

| 5 | The terms ‘pāp’, ‘doṣ’, ‘karma’, and ‘karmic residue’ are used interchangeably insofar as they are semantic variants denoting the invisible substances to be expiated in rites of purification. |

| 6 | The Nars’ disposition in Kahikas, their preponderance in Kullu, and the popular perception of the western gods of Mandi as migrants from Kullu suggest the community’s appellation may derive from the Kullui word for ‘shameless’ (natu). |

| 7 | The Nars share their OBC status with the ascetic turned householder community of Naths. That both groups are associated with sorcery and showmanship may hint at a shared ancestry, although no such claims appear in written sources nor were they advanced during fieldwork. |

| 8 | Nars would, however, ‘also consecrate and purify houses’, indicating a slightly elevated rank in the social hierarchy than mahabrahmins (Rose 1919, vol. 3, p. 157). On the latter today, see Parry (1994). |

| 9 | The pret palu could also be sent off on an elephant (hathidan), recalling the rite’s Nepali variant (Emerson n.d., fo. 560). A near similar rite was performed in the neighbouring kingdom of Chamba (also in Himachal Pradesh), only that the scapegoat would there leave the kingdom on the very same day in which the funerary rites were completed (Hutchison and Vogel 1933, Appendix VII, p. ix). |

| 10 | Informants in Laran Kelo claimed the festival is named after the canopy. Thakur (1997, p. 158) suggests an etymology based on the canopy’s ‘branches’ (Skt. kashkita), while Emerson (n.d., chp. IX) reasonably linked it to the ritual’s goal of ‘expiation’ (khaya). |

| 11 | The device in this instance was about half the size indicated by Emerson, but otherwise similar in shape and usage. Given the Nars’ alleged provenance as Indra’s musicians, the term ḍāḍh may be interpreted as a derivative of Shiva’s ḍamru drum. |

| 12 | The shape of the ḍāḍh may also be interpreted as an approximation of the Puranic vision of the universe (with seven higher and lower worlds stretching in opposite directions from a narrow earthly centre around Mount Meru), or, with a slight stretch of the imagination, as a smoother, rounded version of the thunderbolt (dorje) of Tibetan (Spiti?) cultures. |

| 13 | Dancing with weapons is a prominent feature of the Chuhar Valley Kahikas (Emerson n.d.; Thakur 1997). |

| 14 | The number of public rounds was determined by the number of communities (and their presiding deities) that accepted the hosts’ invitation to the Kahika with a performance enacted for each visitor upon arrival. In between these rounds, the Nar performed chidra rites for private families under the ritual canopy. |

| 15 | Nars are also known to perform this type of chidra upon request, the procedure taking place in the courtyard of one of the aggrieved parties and largely following the course outlined above, with the exception of dabru grass substituting for the ritual cord (Berti 2012, p. 161; Thakur 1997, p. 161). The Nars in Laran Kelo performed similar services at selected households upon the conclusion of the main ritual. |

| 16 | The multitude of tangible and ephemeral parties involved in communal chidras seem to justify its verbatim translation as ‘perforated’ (or the semantically related ‘pierced’ or ‘torn asunder’) instead of the ‘cut’ used to describe the more limited versions of the rite. In noun form, chidra denotes an ‘aperture’, a ‘weak point’, a ‘gap’, which in the context of the spirit-infested world of Kullu signifies the entry into ‘someone’s body through his vulnerable point’ (Tāntrikābhidhānakośa II 2004, p. 257). |

| 17 | As with the commodities used for the construction of the ritual space, the grains (alongside a one rupee coin) are supplied from the storehouse of the god-king, who thus assists in the public expiation of sin. |

| 18 | The precise method of ‘killing’ differs between locations. In 1910s-Hurang, the Nar would lose consciousness by facing the deity’s image inside its temple (Emerson n.d., p. 409), whereas on other occasions it was affected through the possessed mediums (Thakur 1997, p. 162), by tying an image (mohra) of the deity around the victim’s neck, or by the drinking of an unidentified ‘poisonous’ potion (Chaudhary 2013). In certain cases, a medical doctor is brought to affirm that the Nar is ‘really dead’ (personal communication, Arjun Kumar, 24 August 2016). |

| 19 | The Nars’ status as a simultaneously socially inferior and quasi-divine species (jati) seems to account for their healing powers. As the Naran explained, ‘when we speak of it, all sins and faults are removed’ (jab ham bolte hain, sare pap-dosh dur calate hain). |

| 20 | Stories of Nars failing to revive during Kahikas frequently surfaced in conversations, but enquiries in the villages where these mishaps were alleged to have occurred were invariably denied by their residents (who nonetheless pointed to other sites where such ritual failures supposedly took place). |

| 21 | This is in keeping with similar contests between male and female divinities in Indic and Tibetan traditions, e.g., Handelman and Shulman (1997); Dotson (2015), respectively. |

| 22 | For an insightful appraisal of Malana’s supposed ‘remoteness’, see Axelby (2015). |

| 23 | During the Kahika of Laran Kelo, certain members of the public also addressed the Naran as ‘Sita’. |

| 24 | Notably, the Kahika is not mentioned in the earlier report on Malana (Lyall 1874), suggesting it was either ‘revived’ at the turn of the century (as in 1950s-Laran Kelo) or simply escaped its author’s attention. |

| 25 | The data from Malana was collected in the 1880–90s (there is no mention of the rite in Lyall’s 1874 account, but that does not mean it wasn’t performed). Emerson’s study of Hurang would only have been researched in the 1910s, that is two to three decades later. |

| 26 | The purifying powers attributed to Khas virgins in early twentieth century-funerary rites support this reading. Thus, in the periodic feasts held for nourishing the souls of the dead in the four years following cremation, virgins were ‘often included’ alongside Brahmins (Emerson n.d., p. 879). While Emerson (n.d., pp. 401–13) was cognizant of the Malana variant of the Kahika, his interpretation avoids theological speculation to centre on the Narans’ apparent constitution of Himalayan ‘temple girls’ (devadasis) found in the plains. |

| 27 | The procedural construction of a sacred space centred on a yantra thus hints at an adoption of Brahmanical forms of worship, while the summoning of deities into the Nar’s body, supports the nominal ‘mixing of the sexes’ underlined by colonial commentators as evidence of folk (laukik) Tantra. |

| 28 | In both cases supernatural phenomenon are handled by their summoning to a particular site (the medium’s body/the Kahika canopy and the Nars), where they are contained over the course of the ritual, and whence they are ultimately distanced, see Jassal (2017, pp. 143–45). |

| 29 | Despite origins in Indo-European languages, the proximity of Kullu to the Tibetan cultural zone and the Nars’ apparent provenance therein may point to links between chidra and the phonetically and functionally similar practise of (Bön and Buddhist) chöd; my thanks to Marc des Jardins for raising this point. On chöd in the Bön tradition, see Chaoul (2008), for a Tibetan Buddhist elaboration on ritual piercing, see this issue’s Dachille (2017). |

| 30 | Underlining the importance of the Kahika, coverage of the festival appeared on the first page of local papers rather than the back pages where stories on religious events habitually appear. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).