Islamic Schooling in the Cultural West: A Systematic Review of the Issues Concerning School Choice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- the purpose and nature of Islamic schooling,

- (2)

- parental wishes; and

- (3)

- the quality of Islamic schooling.

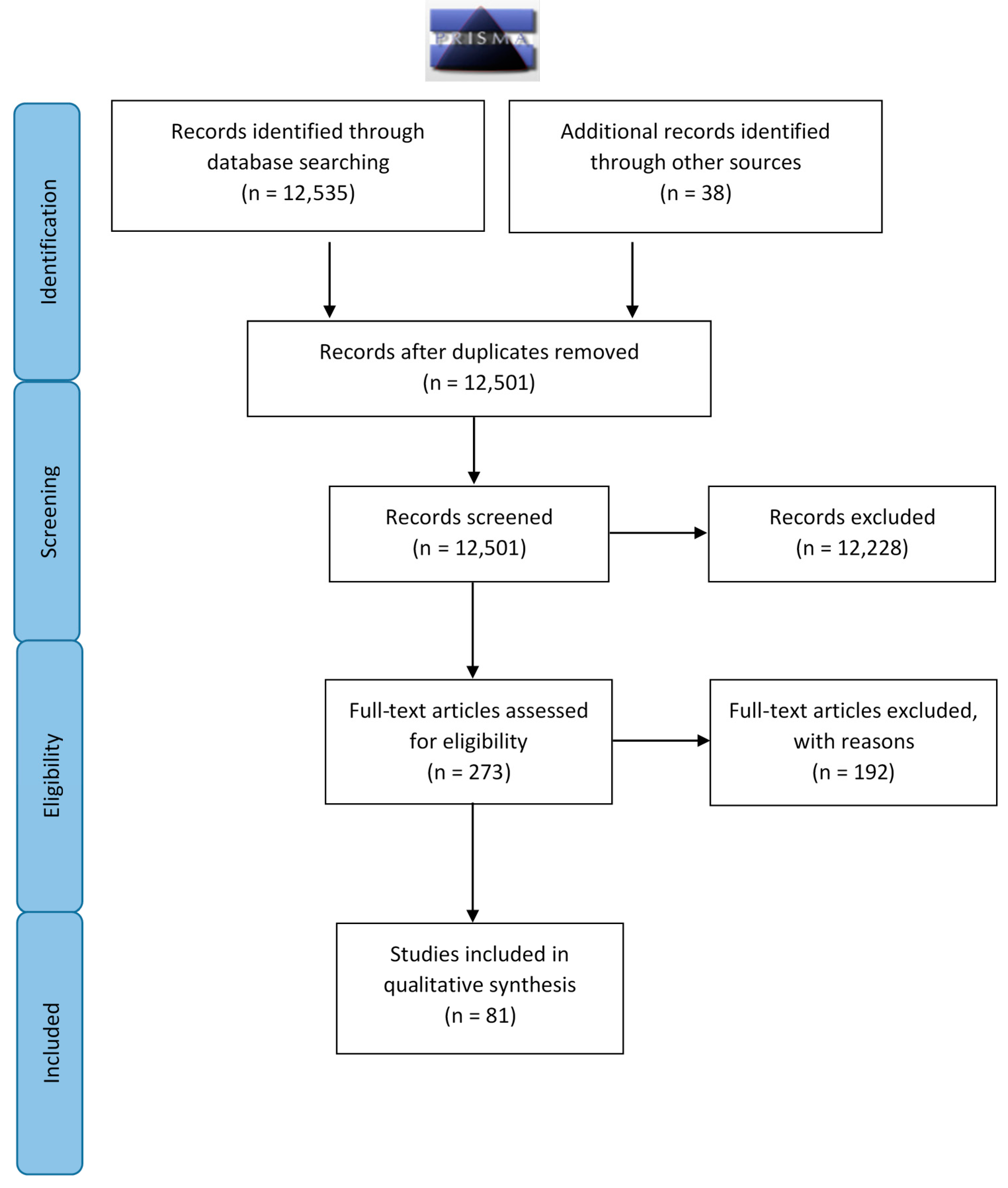

2. Method

2.1. Details of Computerized Search

2.2. Selection Process and Information Retrieval

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Strengths and Weakness of the Search Process

3. Results

3.1. The Purpose and Nature of Islamic Schooling

Countries Having Extensive Government Support for Islamic Schooling

Countries Having Full Government Support for Islamic Schooling

Countries Having Some Government Support for Islamic Schooling

Countries Having no Government Support for Islamic Schooling

3.2. Parental Wishes

3.3. The Quality of Islamic Schooling

4. Discussion

Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbas, Tahir. 2004. The Education of British South Asians: Religion, Culture and Social Class. London: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Abd-El-Hafez, Alaa Karem. 2015. Alternative-Specific and Case-Specific Factors Involved in the Decisions of Islamic School Teachers Affecting Teacher Retention: A Discrete Choice Experiment. Ph.D. Dissertation, (Order No. 10032305). CW Post Center, Long Island University, Brooklyn & Brookville, New York, NY, USA, December. [Google Scholar]

- Agirdag, Orhan, Geert Driessen, and Michael S. Merry. 2017. The Catholic school advantage and common school effect examined: A comparison between Muslim immigrant and native pupils in Flanders. School Effectiveness and School Improvement 28: 123–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Iftikhar. 2002. The needs of Muslim children can be met only through Muslim schools. The Guardian, May 22. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Lawati, Fatma A.K., and Scott L. Hunsaker. 2007. Differentiation for the gifted in American Islamic schools. Journal for the Education of the Gifted 30: 500–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, Muhammad, and Qadir Bakhsh. 2002. State Policies towards Muslims in Britain. A Research Report. Coventry: Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations, University of Warwick. [Google Scholar]

- Badawi, Hoda. 2006. Why Islamic schools. Islamic Horizons 35: 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, Edien. 2000. Dutch Islam: Young people, learning and integration. Current Sociology 48: 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basford, Letitia, and Heather Megarry Traeger. 2014. A Somali school in Minneapolis. In Proud to Be Different: Ethnocentric Niche Charter Schools in America. Edited by Robert A. Fox and Nina K. Buchanan. New York: R&L Education, pp. 125–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bergen, Peter, and Swati Pandey. 2005. The Madrassa Myth. New York Times, June 14. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund, Jenny. 2011. Global questions in the classroom: The formulation of Islamic Religious Education at Muslim schools in Sweden. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 32: 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, Jenny. 2012. Muslim schools in the Nordic countries. In Islam (Instruction) in State-Funded Schools: Country Reports. Edited by Gracienne De Lauwers, Jan De Groof and Paul De Hert. Tilburg: Tilburg Institute for Law, Technology, and Society, pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund, Jenny. 2015. Publicly funded Islamic education in Europe and the United States. The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World Analysis Paper No. 21. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/research/islamic-religious-education-in-europe-and-the-united-states/ (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Berner, Ashley Rogers. 2017. No One Way to School: Pluralism and American Public Education. New York: Palgrave/Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Bleher, Sahib Mustaqim. 1996. A programme for Muslim Education in a non-Muslim society. In Issues in Islamic Education. London: Muslim Education Trust, pp. 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Marinović Bobinac, Ankica, and Dinka Marinović Jerolimov. 2006. Religious education in Croatia. In Religion and Pluralism in Education: Comparative Approaches in the Western Balkans. Edited by Zorica Kuburić and Christian Moe. Novi Sad: The Centre for Empirical Researches on Religion (CEIR), pp. 39–72. [Google Scholar]

- Branch, Gregory F., Eric A. Hanushek, and Steven G. Rivkin. 2013. School leaders matter. Education Next 13: 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bugg, Laura, and Nicole Gurran. 2011. Urban planning process and discourses in the refusal of Islamic schools in Sydney, Australia. Australian Planner 48: 281–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, David E. 2008. The civic side of school choice: An empirical analysis of civic education in public and private schools. BYU L Reviews 2: 487–523. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, Tufyal. 2005. Muslims in the UK: Policies for Engaged Citizens. Budapest: Central European University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clyne, Irene Donohoue. 1998. Cultural diversity and the curriculum: The Muslim experience in Australia. European Journal of Intercultural Studies 9: 279–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clyne, Irene Donohue. 2001. Educating Muslim children in Australia. In Muslim Communities in Australia. Edited by Shahram Akbarzadeh and Abdullah Saeed. Sydney: UNSW Press, pp. 116–37. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, Maurice Irfan. 2004. Education and Islam: A new strategic approach. Race Equality Teaching 22: 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, Andrew. 1999. Market Education: The Unknown History. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Cristillo, Louis. 2009. The case for the Muslim school as a civil society actor. In Educating the Muslims of America. Edited by Yvonne Y. Haddad, Farid Senzai and Jane I. Smith. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Daun, Holger, and Reza Arjmand. 2005. Education in Europe and Muslim demands for competitive and moral education. International Review of Education 51: 403–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, Yolanda. 2017. Muslim American families and their child’s education in America. In Family Involvement in Faith-Based Schools. Edited by Diana B. Hiatt-Michael. Charlotte: IAP, pp. 111–30. [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis, Corey Adam, and Heidi Holmes Erickson. 2018. What leads to successful school choice programs: A review of the theories and evidence. Cato Journal 38: 247. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, Gunther, and Nadia El-Shohoumi. 2005. Muslim Women in Southern Spain: Stepdaughters of Al-Andalus. La Jolla: Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, UCSD. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, Gunther. 2006. Invisibilizing or ethnicizing religious diversity? The transition of religious education towards pluralism in contemporary Spain. In Religion and Education in Europe: Developments, Contexts and Debates. Edited by Robert Jackson, Siebren Miedema, Wolfram Weisse and Jean-Paul Willaime. Münster: Waxmann Verlag, pp. 103–32. [Google Scholar]

- Driessen, Geert W.J.M., and Jeff J. Bezemer. 1999. Background and achievement levels of Islamic schools in the Netherlands: Are the reservations justified? Race Ethnicity and Education 2: 235–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessen, Geert, and Pim Valkenberg. 2000. Islamic schools in the Netherlands: compromising between identity and quality? British Journal of Religious Education 23: 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dronkers, Jaap. 2016. Islamic primary schools in The Netherlands. Journal of School Choice 10: 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durant, Will. 1950. The Age of Faith: A History of Medieval Civilization-Christian, Islamic, and Judaic-from Constantine to Dante: AD 325–1300. The Story of Civilization, Part Four. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, Vernon O. 2004. A History of the Muslim World to 1405: the Making of A Civilization. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Elacqua, Gregory, Mark Schneider, and Jack Buckley. 2006. School choice in Chile: Is it class or the classroom? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 25: 577–601. [Google Scholar]

- Elashi, Fadwa B., Candice M. Mills, and Meridith G. Grant. 2010. In-group and out-group attitudes of Muslim children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 31: 379–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbih, Randa. 2012. Debates in the literature on Islamic schools. Educational Studies 48: 156–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhaldy, Feryal Y. 1996. Analysis of Parental Choice: Islamic School Enrollment in Florida. Ph.D. Dissertation, Order No. 9638566. University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, USA. Summer Term. [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy, Mona. 2013. Female Leadership in Islamic Schools in the United States of America: Prevalence, Obstacles, and Challenges. Ph.D. Dissertation, Order No. 3557727. The George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA, May 19. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Robert A., and N. K. Buchanan, eds. 2017. The Wiley Handbook of School Choice. Malden: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Fuess, Albrecht. 2007. Islamic religious education in Western Europe: Models of integration and the German approach. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 27: 215–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, Charles Leslie, Jan De Groof, and Cara Stillings Candal. 2012. Balancing Freedom, Autonomy and Accountability in Education. Nijmegen: Wolf Legal Publishers, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn, Charles Leslie, Munirah Alaboudi, Richard Fournier, and Katherine Meyer Moran. 2018. Forming Muslim-American citizens: Islamic schools as cultural mediators. In Muslim Educators in American Communities. Edited by Charles Leslie Glenn. Charlotte: IAP. [Google Scholar]

- Grytnes, Renate. 2004. Muslimsk privatskole—en trussel eller et uttrykk for multikulturalisme? Norsk pedagogisk tidsskrift 88: 145–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gulson, Kalervo N., and P. Taylor Webb. 2012. Education policy racialisations: Afrocentric schools, Islamic schools, and the new enunciations of equity. Journal of Education Policy 27: 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulson, Kalervo N., and P. Taylor Webb. 2013. ‘We had to hide we’re Muslim’: Ambient fear, Islamic schools and the geographies of race and religion. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 34: 628–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, Amy. 1999. Democratic Education. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, Yvonne Yazbeck, and Adair T. Lummis. 1987. Islamic Values in the United States: A comparative Study. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, Zubaida, and John F. Bell. 2001. Evaluating the performances of minority ethnic pupils in secondary schools. Oxford Review of Education 27: 357–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, Yasmin. 2013. Making Muslims: The Politics of Religious Identity Construction and Victoria’s Islamic Schools. Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations 24: 501–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herweijer, Lex. 2009. Making up the Gap: Migrant Education in the Netherlands. The Hague: Netherlands Institute for Social Research (SCP). [Google Scholar]

- Hewer, Chris. 2001. Schools for Muslims. Oxford Review of Education 27: 515–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, Jeremy. 2000. Religious requirements: The case for Roman Catholic schools in the 1940s and Muslim schools in the 1990s. Journal of Beliefs and Values 21: 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Serena, and Jen’nan Ghazal Read. 2015. Islamic schools in the United States and England: Implications for integration and social cohesion. Social Compass 62: 556–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Independent School Council of Australia. 2014. Independent Schooling in Australia Snapshot 2014. Available online: http://isca.edu.au/ (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Ihle, Annette Haaber. 2007. Magt, medborgerskab og Muslimska friskoler i Danmark. Copenhagen: Institut for tvärkulturelle of regionale studier, Köbenhavns Universitet. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Peter. 2012. Islamic schools in Australia. The La Trobe Journal 89: 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jozsa, Dan-Paul. 2006. Islam and Education in Europe, with special reference to Austria, England, France, Germany and the Netherlands. In Religion and Education in Europe: Developments, Contexts and Debates. Edited by Robert Jackson, Siebren Miedema, Wolfram Weisse and Jean-Paul Willaime. Münster: Waxmann Verlag, pp. 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer, Michael. 2005. Islamkunde in deutscher Sprache in Nordrhein-Westfalen: Kontext, Geschichte, Verlauf und Akzeptanz eines Schulversuchs. Münster: LIT Verlag, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Patricia. 1999. Integration and identity in Muslim schools: Britain, United States and Montreal. Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 10: 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyworth, Karen. 2006. Trial by fire: Islamic schools after 9–11. Islamic Schools League of America. Available online: https://theisla.org/research/ (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Kuburić, Zorica, and Christian Moe, eds. 2006. Religion and Pluralism in Education: Comparative Approaches in the Western Balkans. Novi Sad: The Centre for Empirical Researches on Religion (CEIR). [Google Scholar]

- Kuburić, Zorica, and Milan Vukomanović. 2006. Religious Education: The Case of Serbia. In Religion and Pluralism in Education: Comparative Approaches in the Western Balkans. Edited by Zorica Kuburić and Christian Moe. Novi Sad: The Centre for Empirical Researches on Religion (CEIR), pp. 107–38. [Google Scholar]

- Makdisi, George. 1961. Muslim institutions of learning in eleventh-century Baghdad. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 24: 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkawi, Fathi. 2004. Future of Muslim education. Islamic Horizons 33: 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Maranto, Robert, M. Danish Shakeel, and Evan Rhinesmith. 2018. Immigrant educational entrepreneurs: Measuring the performance of Turkish-founded charter schools. In Muslim Educators in American Communities. Edited by Charles Leslie Glenn. Charlotte: IAP. [Google Scholar]

- Martikainen, Tuomas. 2004. Islam i Finland. Svensk religionshistorisk årsskrift 13: 105–23. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, Priscilla. 2009. Muslim Homeschooling. In Educating the Muslims of America. Edited by Yvonne Y. Haddad, Farid Senzai and Jane I. Smith. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 109–22. [Google Scholar]

- Matevski, Zoran, Etem Aziri, and Goce Velichkovski. 2006. Introducing Religious Education in Macedonia. In Religion and Pluralism in Education: Comparative Approaches in the Western Balkans. Edited by Zorica Kuburić and Christian Moe. Novi Sad: The Centre for Empirical Researches on Religion (CEIR), pp. 139–60. [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew, Marie. 2010. The Muslim community and education in Quebec: Controversies and mutual adaptation. Journal of International Migration and Integration [Revue de l’integration et de la migration international] 11: 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCreery, Elaine, Liz Jones, and Rachel Holmes. 2007. Why do Muslim parents want Muslim schools? Early Years 27: 203–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeni, Elif. 2013. An analysis of Islamic schooling in Austria–a contribution to Muslim integration or tool for segregation? In International Symposium on Religious Studies and Global Peace. Edited by Muhiddin Okumuşlar, Necmeddin Güney and Aytekin Şenzeybek. Konya: Türkiye Imam Hatipliler Vakfi Yayinlari, pp. 119–34. [Google Scholar]

- Meer, Nasar. 2007. Muslim schools in Britain: Challenging mobilisations or logical developments? Asia Pacific Journal of Education 27: 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meer, Nasar. 2010. Citizenship, Identity and the Politics of Multiculturalism: The Rise of Muslim Consciousness. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Memon, Nadeem. 2006. Colonizing Muslim Schools from within: An analysis of neo-liberal practices in Toronto’s Islamic schools. Paper presented at the Rage and Hope Conference, OISE/University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, February 24. [Google Scholar]

- Memon, Nadeem. 2009. From Protest to Praxis: A History of Islamic Schools in North America. Ph.D. Dissertation, Order No. NR61032. University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Memon, Nadeem. 2010. Social consciousness in Canadian Islamic schools? Journal of International Migration and Integration/Revue de l’integration et de la migration internationale 11: 109–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, Nadeem. 2011. What Islamic school teachers want: Towards developing an Islamic teacher education programme. British Journal of Religious Education 33: 285–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, Michael S. 2005. Advocacy and involvement: The role of parents in western Islamic schools. Religious Education 100: 374–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, Michael S. 2007. Culture, Identity, and Islamic Schooling: A Philosophical Approach. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Merry, Michael S., and Geert Driessen. 2005. Islamic schools in three western countries: Policy and procedure. Comparative Education 41: 411–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, Michael S., and Geert Driessen. 2009. Islamic schools in the US and Netherlands: Inhibiting or enhancing democratic dispositions? In Alternative Education for the 21st Century: Philosophies, Approaches, Visions. Edited by Phillip A. Woods and Glenys J. Woods. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 101–22. [Google Scholar]

- Merry, Michael S., and Geert Driessen. 2016. On the right track? Islamic schools in the Netherlands after an era of turmoil. Race Ethnicity and Education 19: 856–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, Mahdi. 2005. A Comparison of the Mathematical Performance of Grade 3 Students in Provincial Public and Islamic Private Schools in Ontario. Master’s Thesis, Order No. MR17051. University of Windsor, Windsor, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, and Douglas G. Altman. 2009. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6: e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohme, Gunnel. 2017. Somali Swedes’ reasons for choosing a Muslim-profiled school—Recognition and educational ambitions as important influencing factors. Journal of School Choice 11: 239–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molook, Roghanizad. 1990. Full-time Muslim Schools in the United States: 1970–1990. Ph.D. Dissertation, Order No. 9110341. University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Moreras, Jordi. 2005. La situation de l’enseignement musulman en Espagne. In Des Maîtres et des Dieux: écoles et religions en Europe. Edited by Séverine Mathieu and Jean-Paul Willaime. Paris: Belin, pp. 165–79. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Ingrid M. 2005. Islamische Religiöse Unterweisung in deutscher Sprache—Ergebnisse der wissenschaftlichen Begleitung. Munich: Developed on behalf of the Bavarian Ministry of Education and Culture, State Institute for School Quality and Educational Research. [Google Scholar]

- Muralidharan, Karthik, and Venkatesh Sundararaman. 2015. The aggregate effect of school choice: Evidence from a two-stage experiment in India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 130: 1011–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musharraf, Muhammad Nabeel. 2015. Islamic Education in Europe—A Comprehensive Analysis, 1st ed. Maddington: Australian Islamic Library, Available online: https://archive.org/details/EuropeanEducationPaper (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Musharraf, Muhammad Nabeel, and Fatima Bushra Nabeel. 2015. Schooling options for Muslim children living in Muslim-minority countries—A thematic literature review. International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Research 3: 29–62. [Google Scholar]

- Nimer, Moham. 2002. Muslims in American public life. In Muslims in the West: From Sojourners to Citizens. Edited by Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 169–86. [Google Scholar]

- Niyozov, Sarfaroz, and Gary Pluim. 2009. Teachers’ perspectives on the education of Muslim students: A missing voice in Muslim education research. Curriculum Inquiry 39: 637–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyman, Ann-Sofie. 2005. Intolerance and Discrimination against Muslims in the EU. Developments Since September 11. Vienna: International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights [IHF]. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, Maureen Roslyn. 2010. Muslim Mothers: Pioneers of Islamic Education in America. Ph.D. Dissertation, Order No. 3427067. College of Notre Dame of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA, March 12. [Google Scholar]

- Osler, Audrey, and Zahida Hussain. 1995. Parental choice and schooling: Some factors influencing Muslim mothers’ decisions about the education of their daughters. Cambridge Journal of Education 25: 327–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjwani, Farid. 2004. The “Islamic” in Islamic education: Assessing the discourse. Current Issues in Comparative Education 7: 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Parker-Jenkins, Marie. 2002. Equal access to state funding: The case of Muslim schools in Britain. Race, Ethnicity and Education 5: 273–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker-Jenkins, Marie, Dimitra Hartas, and Barrie A. Irving. 2005. In Good Faith: Schools, Religion and Public Funding. Burlington: Ashgate Pub Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2016. Religion and Education Around the World. Available online: http://www.pewforum.org/2016/12/13/religion-and-education-around-the-world/ (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Raihini, Raihini, and David Gurr. 2010. Parental involvement in an Islamic school in Australia: An exploratory study. Leading and Managing 16: 62. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, Hakim M., and Zakiyyah Muhammad. 1992. The Sister Clara Muhammad schools: Pioneers in the development of Islamic education in America. The Journal of Negro Education 61: 178–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaranaho, Tuula. 2009. Constructing Islamic identity: The education of Islam in Finnish state school. In Islamic education in Europe. Edited by Ednan Aslan. Vienna: Böhlau Verlag, pp. 109–28. [Google Scholar]

- Scharbrodt, Oliver, and Tuula Sakaranaho. 2011. Islam and Muslims in the Republic of Ireland: An introduction to the special issue. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 31: 469–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, Peter, ed. 2000. Religious Education in Europe: A Collection of Basic Information about RE in European Countries. Münster: Comenius-Inst. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Sara, and Di McNeish. 2012. Leadership and Faith Schools: Issues and Challenges. Nottingham: National College for School Leadership. [Google Scholar]

- Shadid, Wasif A.R., and Pieter Sjoerd van Koningsveld. 1992. Islamic primary schools. In Islam in Dutch Society: Current Developments and Future Prospects. Edited by Wasif A.R. Shadid and Pieter Sjoerd van Koningsveld. Kampen: Kok Pharos, pp. 107–23. [Google Scholar]

- Shadid, Wasif A.R., and Pieter Sjoerd van Koningsveld. 1996. Muslims in the Margin: Political Responses to the Presence of Islam in Western Europe. Kampen: Kok Pharos, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Shadid, Wasif A.R., and Pieter Sjoerd van Koningsveld. 2006. Islamic religious education in the Netherlands. European Education 38: 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Saeeda. 2012. Muslim schools in secular societies: Persistence or resistance! British Journal of Religious Education 34: 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, M. Danish, and Patrick John Wolf. 2018. Does private Islamic schooling promote terrorism? An analysis of the educational background of successful American homegrown terrorists. Hungarian Educational Research Journal 8: 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirin, Selcuk R., Patrice Ryce, and Madeeha Mir. 2009. How teachers’ values affect their evaluation of children of immigrants: Findings from Islamic and public schools. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 24: 463–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Jane I. 2000. Islam in America. New York: Colombia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stotsky, Sandra. 2011. The stealth curriculum. In Saudi Arabia and the Global Islamic Terrorist Network. Edited by Sarah N. Stern. New York: Palgrave/Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ter Avest, K. H., and Marjoke Rietveld-van Wingerden. 2017. Half a century of Islamic education in Dutch schools. British Journal of Religious Education 39: 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teske, Paul, and Mark Schneider. 2001. What research can tell policymakers about school choice. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 20: 609–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thohbani, Shiraz. 2010. Islam in the School Curriculum: Symbolic Pedagogy and Cultural Claims. London: Continuum International. [Google Scholar]

- Tinker, Claire. 2009. Rights, social cohesion and identity: Arguments for and against state-funded Muslim schools in Britain. Race Ethnicity and Education 12: 539–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivitt, Julie R., and Patrick J. Wolf. 2011. School choice and the branding of Catholic schools. Education Finance and Policy 6: 202–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ummid News. 2015. 40% of Muslim World’s Population Unable to Read or Write. Available online: http://www.ummid.com/news/2015/February/11.02.2015/literacy-in-muslim-world.html (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Van den Kerchove, Anna. 2009. Islam within the framework of “Laïcité”: Islam and Education in France. In Islam in Education in European Countries. Pedagogical Concepts and Empirical Findings. Edited by Aurora Alvarez Veinguer, Gunther Dietz, Dan-Paul Jozsa and Thorsten Knauth. Münster: Waxmann Verlag, pp. 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Van Kessel, N. 2004. Zorg Om 120 Extra Moslimscholen [Worries about 120 Extra Islamic Schools]. Algemeen Dagblad, March 6. [Google Scholar]

- Versteegt, Inge, and Marcel Maussen. 2011. The Netherlands: challenging diversity in education and school life. Accept-Pluralism Working Paper 11: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Derriks, M., W. M. M. H. Veugelers, and E. de Kat. 2004. Aandacht voor geestelijke stromingen in het penbaar Onderwijs [Attention for Spiritual Movements at Public Schools]. Amsterdam: Institute for Teacher Training, University of Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Willaime, Jean-Paul. 2006. Different models for religion and education in Europe. In Religion and Education in Europe: Developments, Contexts and Debates. Edited by Robert Jackson, Siebren Miedema, Wolfram Weisse and Jean-Paul Willaime. Münster: Waxmann Verlag, pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, Patrick J., and Stephen Macedo, eds. 2004. Educating Citizens: International Perspectives on Civic Values and School Choice. Washington: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, Patrick J. 2007. Civics Exam. Education Next. Available online: http://educationnext.org/civics-exam/ (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Wolf, Patrick J. 2018. Programs Benefit Disadvantaged Students. Education Next. Available online: https://www.educationnext.org/programs-benefit-disadvantaged-students-forum-private-school-choice/ (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Zine, Jasmin. 2006. Unveiled sentiments: Gendered Islamophobia and experiences of veiling among Muslim girls in a Canadian Islamic school. Equity & Excellence in Education 39: 239–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zine, Jasmin. 2007. Safe havens or religious ‘ghettos’? Narratives of Islamic schooling in Canada. Race Ethnicity and Education 10: 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zine, Jasmin. 2008. Honour and identity: An ethnographic account of Muslim girls in a Canadian Islamic school. TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies 19: 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. | See English translation of Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī, Iḥyāʾ ʿUlūm al-Dīn (Revival of the Religious Sciences), Volume 1, Book 1. Available online: https://www.ghazali.org/ihya/english/index.html. |

| 2. | The use of terms confessional, inter-confessional and denominational is relevant for policymakers and stakeholders in Islamic schooling, as education laws are often written in the traditional vernacular of a nation. In contrast, sects and schools of jurisprudence in Islam do not have equivalent definitions. |

| 3. | Most literature retrieved in the search was not published in high-ranking journals. Findings drawn from weak research may seem more consistent than in reality. Review by experts in education policy was used to address this issue. |

| 4. | Sunan Ibn Majah. Chapter 1, The Book of the Sunnah, Hadith No. 224. |

| 5. | Much of Sunni Islam is devolved among jurisprudential schools of thoughts. Where centralization exists in parts of the Sunni religious structure, it can be ascribed to politics. Sunni Islam has the concept of a governing leader appointed by the people. In contrast, Shia Islam has the concept of a leader appointed by God, making it much less devolved in comparison to Sunni Islam. Any deviation in the concept of the divinely appointed leader in Shia Islam is theological and unlike the variation among schools of jurisprudence in Sunni Islam. Thus, differences in Sunni Islam are more cultural and jurisprudential, whereas differences in Shia Islam are more theological. |

| 6. | The Islamic theologians agree that the Quran is essentially the Arabic text that was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. Any translation or commentary of the Quran is termed as meaning of the Quran but not the ‘word of God’ in Islamic theology. |

| 7. | In 1791, the 10th Amendment stated, “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” Public education is not one of those federal powers, and so historically has been delegated to the local and state governments. |

| 8. | |

| 9. | Arabic word for permissible in Islamic law. Quite often, it is used to describe food but it encompasses every religious and secular aspect of a Muslim’s daily life. |

| 10. | Arabic term for a leader. In the context of a mosque, it refers to the leader who leads the congregational prayers and acts as a spiritual guide for the local Muslim community. |

| 11. | The Islamic concept of Umma i.e., one nationhood of Muslims is often more appealing to Muslim converts in comparison to mere cultural Muslims. |

| 12. |

| Number of Articles | |

|---|---|

| Search 1 (University Library) | |

| Three library sources (EBSCO, JSTOR, ProQuest) | 935 |

| Excluded Based on Title and/or Abstract | −795 |

| Remaining articles (EBSCO, JSTOR, ProQuest) | 140 |

| Duplicates Removed | −36 |

| Remaining Articles (EBSCO, JSTOR, ProQuest) | 104 |

| Search 2 (Google Scholar) | |

| Number of Google Scholar Sources Initially Found | 11,600 |

| Excluded Based on Title and/or Abstract | −11,433 |

| Remaining Google Articles | 167 |

| Duplicates Removed | −1 |

| Remaining Articles (Google Scholar) | 166 |

| Sum of Remaining Articles (Both Searches) | 270 |

| Duplicates Removed | −35 |

| Remaining articles | 235 |

| Excluded Based on Full Article | −192 |

| Other studies added | +38 |

| Total search results | 81 |

| Study outside cultural west | 12 |

| Not related to Islamic schools (e.g., Muslim women, arts, dress codes, preschool) | 14 |

| Religious schooling in general (not Islamic schooling specific) | 7 |

| Different question related to Islamic schools (e.g., creationism, democracy, globalization, politics, Islamic theology, Christian-Muslim relations, refugees) | 30 |

| Earlier/duplicate version of an included study | 4 |

| Duplicate version of an excluded study | 1 |

| Commentary, book review or opinion piece | 57 |

| Newer study looks at the same/broader issues | 39 |

| Lack of study rigor | 28 |

| Total Excluded | 192 |

| Country | Has Islamic Schools | Publicly Funded | Islamic Religious Instruction within Public Schools | Provision of Publicly Funded Teacher Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Germany | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| The Netherlands | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Belgium | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Australia | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Denmark | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Sweden | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| United Kingdom | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Spain | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Serbia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Croatia | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Macedonia | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Finland | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Canada | ✓ | |||

| France | ✓ | |||

| Norway | ✓ | |||

| United States | ✓ |

| Parental Wishes | Corresponding Issues Generated for Schools |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Government support |

|

|

|

| Administrative reforms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pedagogy and curriculum development |

|

|

|

|

| School and staff related improvements |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Communal transformations |

|

|

|

| Guidelines for future research |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shakeel, M.D. Islamic Schooling in the Cultural West: A Systematic Review of the Issues Concerning School Choice. Religions 2018, 9, 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9120392

Shakeel MD. Islamic Schooling in the Cultural West: A Systematic Review of the Issues Concerning School Choice. Religions. 2018; 9(12):392. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9120392

Chicago/Turabian StyleShakeel, M. Danish. 2018. "Islamic Schooling in the Cultural West: A Systematic Review of the Issues Concerning School Choice" Religions 9, no. 12: 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9120392

APA StyleShakeel, M. D. (2018). Islamic Schooling in the Cultural West: A Systematic Review of the Issues Concerning School Choice. Religions, 9(12), 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9120392