Internet Censorship in Arab Countries: Religious and Moral Aspects

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Legal Basis for Internet Censorship in the Arab Countries

and do not argue with the People of the Scripture except in a way that is best (29:46).

I only advise you of one [thing]—that you stand for Allah, [seeking truth] in pairs and individually, and then give thought (34:46).Observe what is in the heavens and earth (10:101).

The best Jihad is to say a word of truth before a tyrant ruler.

- (a)

- Every person has the right to express his thoughts and beliefs so long as he remains within the limits prescribed by the Law. No one, however, is entitled to disseminate falsehood or to circulate reports which may outrage public decency, or to indulge in slander, innuendo or to cast defamatory aspersions on other persons.

- (b)

- There shall be no bar on the dissemination of information provided it does not endanger the security of the society or the state and is confined within the limits imposed by the Law.

- (c)

- No one shall hold in contempt or ridicule the religious beliefs of others or incite public hostility against them; respect for the religious feelings of others is obligatory on all Muslims (Universal Islamic Declaration of Human Rights 1981).

- (a)

- Everyone shall have the right to express his opinion freely in such manner as would not be contrary to the principles of the Shari’ah.

- (b)

- Everyone shall have the right to advocate what is right, and propagate what is good, and warn against what is wrong and evil according to the norms of Islamic Shari’ah.

- (c)

- Information is a vital necessity to society. It may not be exploited or misused in such a way as may violate sanctities and the dignity of Prophets, undermine moral and ethical Values or disintegrate, corrupt or harm society or weaken its faith (Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam 1990).

The State shall guarantee freedom of opinion. Every Jordanian shall be free to express his opinion by speech, in writing, or by means ofphotographic representation and other forms of expression, within the limits of the law.

Newspapers shall not be suspended from publication nor their permits be withdrawn except in accordance with the provisions of the law.

The state shall guarantee freedom of the press, printing and publishing, the media and its independence in accordance with the law.

The religion of the State is Islam, and Islamic Law shall be a main source of legislation.

“the main source of legislation is Islamic law (Shari’ah)”.

The freedom of the press, printing, and publishing is guaranteed according to the terms and conditions prescribed by the Law. Anything that leads to discord, affects the security of State, or prejudices human dignity or rights, is prohibited.(article 31 of Oman’s constitution) (Oman’s Constitution 1996)

Freedom of opinion and scientific research is guaranteed. Everyone has the right to express his opinion and publish it by word of mouth, in writing or otherwise under the rules and conditions laid down by law, provided that the fundamental beliefs of Islamic doctrine are not infringed, the unity of the people is not prejudiced, and discord or sectarianism is not aroused.(article 23 of Bahrain’s constitution) (Bahrain’s Constitution 2002)

The state shall guarantee the freedom and confidentiality of mail, telephone, telegram and all other means of communication, none of which may be censored, searched, exposed, delayed or confiscated except in cases specified by law and according to a court order.(article 53 of Yemen’s constitution) (Yemen’s Constitution 1991)

First. Freedom of expression using all means.Second. Freedom of press, printing, advertisement, media and publication.

No law may be enacted that contradicts the established provisions of Islam.

The freedom of the press is guaranteed and may not be limited by any form of prior censure.

All have the right to express and to disseminate freely and within the sole limits expressly provided by the law, information, ideas and opinions.

Freedom of the press, printing, publication and mass media shall be guaranteed. Censorship on newspapers is forbidden. Warning, suspension or abolition of newspapers by administrative means are prohibited. However, in case of declared state of emergency or in time of war, limited censorship may be imposed on newspapers, publications and mass media in matters related to public safety or for purposes of national security in accordance with the law.

The freedom of conscience and the freedom of opinion are inviolable.

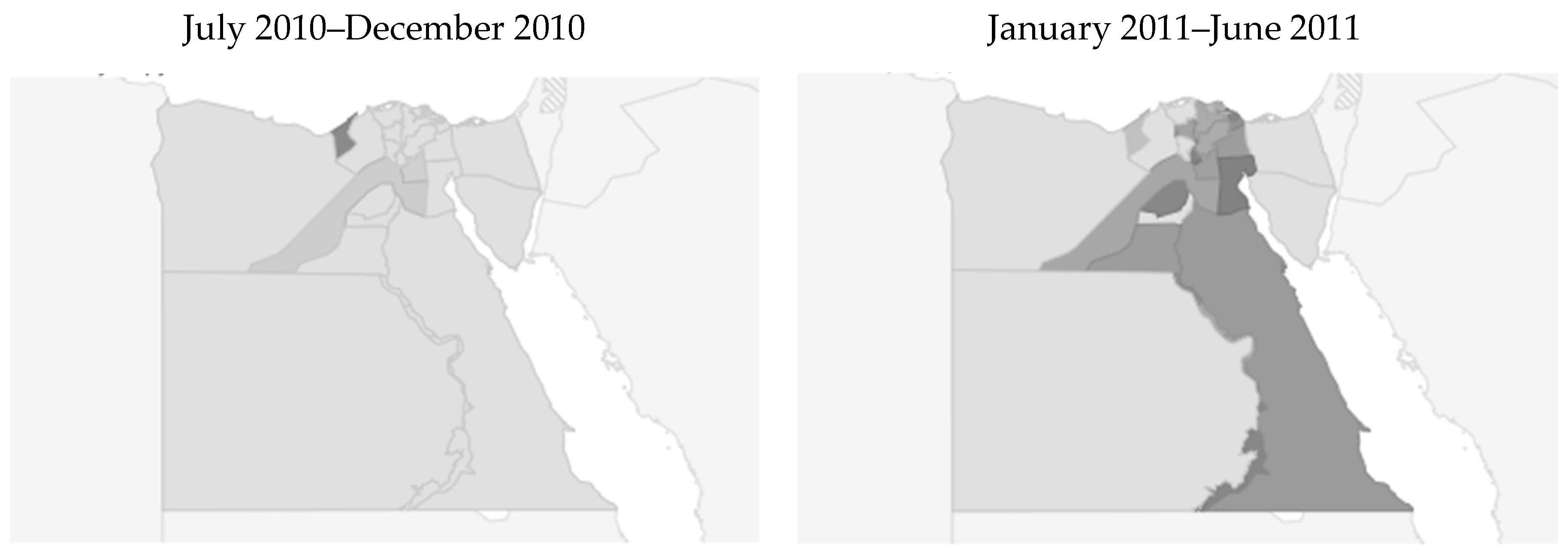

3. Internet Censorship in the Arab World

- -

- to maintain political stability (Libya, Jordan);

- -

- to strengthen national security (Morocco);

- -

- to preserve traditional social values (Oman).

4. Policy vs. Morality

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdulla, Rasha A. 2007. The Internet in the Arab World: Egypt and Beyond. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Aday, Sean, Henry Farrell, Marc Lynch, John Sides, and Deen Freelon. 2012. New Media and Conflict after the Arab Spring. United States Institute of Peace, Peceworks 80: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Al’-Roshd, Said M., ed. 2008. Khadisy Proroka [Hadith of the Prophet]. Perevod i kommentarii I.V. Porokhovoy. 2-ye izd. Moscow: Avanta+. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kandari, Ali, and Mohammed Hasanen. 2012. The impact of the Internet on political attitudes in Kuwait and Egypt. Telematics and Informatics 29: 245–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allagui, Ilhem, and Johanne Kuebler. 2011. The Arab Spring and the Role of ICTs. Introduction. International Journal of Communication 5: 8. [Google Scholar]

- Altermann, John B. 1998. New Media, New Politics? From Satellite Television to the Internet in the Arab World. Washington, DC: The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, John W. 2003. New media, new publics: Reconfiguring the public sphere of Islam. Social Research 70: 887–906. [Google Scholar]

- Arab IP Centre. 2013. Use of Internet in the Arab World. Available online: http://www.arabipcentre.com/use-of-internet-in-the-arab-world.php (accessed on 5 June 2018).

- Arab Social Media Report. 2011. Available online: http://interactiveme.com/2011/06/twitter-usage-in-the-mena-middle-east/ (accessed on 30 December 2017).

- Armando, Salvatore. 2013. New Media, the “Arab Spring,” and the Metamorphosis of the Public Sphere: Beyond Western Assumptions on Collective Agency and Democratic Politics. Constellations 20: 217–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ayubi, Nazih. 2003. Political Islam: Religion and Politics in the Arab World. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrain’s Constitution. 2002. Manama. Available online: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Bahrain_2002.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2018).

- Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 2016. Country Reports on Human Rights Practises for 2016. Available online: https://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/2016humanrightsreport/index.htm?year=2016&dlid=265494#wrapper (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam. 1990. Cairo. Available online: http://www.bahaistudies.net/neurelitism/library/Cairo_Declaration_on_Human_Rights_in_Islam.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Calingaert, Daniel. 2010. Authoritarianism vs. the Internet. Policy Review 160: 63. [Google Scholar]

- Civil Society Development Fund. 2013. Fil’tratsiya kontenta v Internete. Analiz mirovoy praktiki [Content Filtering on the Internet. Analysis of World Practice]. Available online: http://civilfund.ru/Filtraciya_Kontenta_V_ Internete_Analiz_Mirovoy_Praktiki.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2018).

- Constitution of Algeria. 2006. Alger. Available online: https://law.wustl.edu/GSLR/CitationManual/countries/algeria.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Constitution of The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. 1952. Amman. Available online: http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/text.jsp?file_id=227814 (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Constitution of the Syrian Arab Republic. 2012. Damascus. Available online: http://www.voltairenet.org/article173033.html (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Dainotti, Alberto, Claudio Squarcella, Emile Aben, Kimberly C. Claffy, Marco Chiesa, Michele Russo, and Antonio Pescapé. 2011. Analysis of country-wide internet outages caused by censorship. Paper presented at the 2011 ACM SIGCOMM Conference on Internet Measurement Conference, Berlin, Germany, November 2–4; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dalek, Jacub, Lex Gill, Bill Marczak, Sarah McKune, Naser Noor, Joshua Oliver, John Penney, Adam Senft, and Ron Deibert. 2018. Planet Netsweeper. Executive Summary. Available online: https://citizenlab.ca/2018/04/planet-netsweeper/ (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Deibert, Ron J. 2009. The geopolitics of internet control. Censorship, sovereignty, and cyberspace. In Routledge Handbook of Internet Politics. Edited by Andrew Chadwick and Philip N. Howard. London: Taylor & Francis, pp. 323–36. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, Larry J. 2012. Liberation Technology: Social Media and the Struggle for Democracy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Egypt’s Constitution. 1971. Cairo. Available online: http://www.palatauruscentrostudi.eu/doc/EGY_Constitution_1971_EN.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Freedom House. 2011. Freedom on the Net 2011. Available online: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/freedom-net-2011 (accessed on 13 September 2018).

- Freedom House. 2015. Bahrain Freedom on the Net 2015. Available online: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2015/bahrain (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Freedom on the Net. 2018. The Rise of Digital Authoritarianism. Available online: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/freedom-net-2018/rise-digital-authoritarianism (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Google Trends. 2018. Available online: https://www.google.ru/trends/explore (accessed on 24 April 2018).

- Haselton, Bennett. 2013. Smartfilter. Miscategorization and Filtering in Saudi Arabia and UAE. Available online: https://citizenlab.ca/2013/11/smartfilter-miscategorization-filtering-saudi-arabia-uae/ (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Herrera, Linda. 2012. Youth and Citizenship in the Digital Age: A View from Egypt. Harvard Educational Review 82: 333–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofheinz, Albrecht. 2005. The Internet in the Arab world: Playground for political liberalization. International Politics and Society 3: 78–96. [Google Scholar]

- Houissa, Ali. 2000. The Internet predicament in the Middle East and North Africa: Connectivity, access and censorship. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 32: 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Philip N. 2010. The Digital Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Information Technology and Political Islam. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Philip N., and Malcolm R. Parks. 2012. Social media and political change: Capacity, constraint, and consequence. Journal of Communication 62: 359–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Philip N., Sheetal D. Agarwal, and Muzammil M. Hussain. 2011a. When do states disconnect their digital networks? Regime responses to the political uses of social media. The Communication Review 14: 216–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Philip N., Aiden Duffy, Deen Freelon, Muzammil M. Hussain, Will Mari, and Marwa Maziad. 2011b. Opening Closed Regimes: What Was the Role of Social Media during the Arab Spring? ITPI Working Paper. Available online: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/117568/2011_Howard-Duffy-Freelon-Hussain-Mari-Mazaid_PITPI.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y%20 (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Human Rights Watch. 1999. The Internet in the Mideast and North Africa: Free Expression and Censorship. New York: Human Rights Watch. [Google Scholar]

- IFEX. 2017. Why Yemen’s Internet Shutdowns Are so Dangerous to Civilians. Available online: https://www.ifex.org/yemen/2017/12/11/internet-shutdown-houthis/ (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Wayne E. Baker. 2000. Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review 65: 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internet World Stats. 2015. Internet Usage in the Middle East. Available online: http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats5.htm (accessed on 5 June 2018).

- Iraq’s Constitution. 2005. Baghdad. Available online: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Iraq_2005.pdf?lang=en (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Jansen, Fieke. 2010. Digital activism in the Middle East: Mapping issue networks in Egypt, Iran, Syria and Tunisia. Knowledge Management for Development Journal 6: 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karolak, Magdalena M. 2011. Civil Society and Web 2.0 Technology: A Study of Social Media in the Kingdom of Bahrain. Arab Media & Society 13: 1–18. Available online: http://www.arabmediasociety.com/?article=773 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Khalifa, Rashad. 1992. Qur’an. The Final Testament. Authorized English Version. Tucson: Islamic Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Khazen, Jihad. 1999. Censorship and state control of the press in the Arab world. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 4: 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwait’s Constitution of 1962. 1962. Kuwait. Available online: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Kuwait_1992.pdf?lang=en (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Langman, Lauren, and Morris Douglas. 2002. Internet Mediation: A Theory of Alternative Globalization Movements. Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Community Informatics; Edited by M. Gurstein and S. Finquelievich. Montreal. Available online: http://www.csudh.edu/dearhabermas/langmanbk01.htm (accessed on 2 September 2018).

- Lerner, Melissa Y. 2010. Connecting the actual with the virtual: The Internet and social movement theory in the Muslim world—The cases of Iran and Egypt. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 30: 555–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libyan Interim Constitutional Declaration. 2011. Tripoli. Available online: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Libya_2011.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Lifintseva, Tatyana P., Leonid M. Issaev, and Alisa R. Shishkina. 2015. Fitnah: The Afterlife of a Religious Term in Recent Political Protest. Religions 6: 527–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, Catherine. 2010. Study: Are Google Searches Affecting the Stock Market? Time Magazine. November 15. Available online: http://newsfeed.time.com/2010/11/15/google-searches-and-financial-market-fluctuations-linked-and-worrying/ (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Middle East Voices. 2012. Samsung, iPhone, Nokia and the Next Arab Spring. Available online: http://middleeastvoices.voanews.com/2012/05/samsung-iphone-nokia-and-the-next-arab-spring-46703/ (accessed on 15 April 2018).

- Moore, Jina. 2011. Did Twitter, Facebook Really Build a Revolution? Christian Science Monitor. June 30. Available online: http://www.nbcnews.com/id/43596216/ns/technology_and _science-christian_science_monitor/t/did-twitter-facebook-really-build-revolution/ (accessed on 30 June 2018).

- Morocco’s Constitution. 2011. Rabat. Available online: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Morocco_2011?lang=en (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Newsom, Victoria A., and Lengel Lara. 2012. Arab Women, Social Media, and the Arab Spring: Applying the framework of digital reflexivity to analyze gender and online activism. Journal of International Women’s Studies 13: 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Oman’s Constitution. 1996. Muscat. Available online: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Oman_2011?lang=en (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- OpenNet Initiative. 2009. Internet Filtering in the Middle East and North Africa. Available online: https://opennet.net/sites/opennet.net/files/ONI_MENA_2009.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2017).

- Reporters Without Borders. 2016. No Concessions to Media as Indiscriminate Repression Continues in Countries with Pro-Democracy Protests. Available online: https://rsf.org/en/news/no-concessions-media-indiscriminate-repression-continues-countries-pro-democracy-protests (accessed on 12 April 2017).

- Saab, Edmond. 2006. The Independence of the Arab Media. In Arab Media in the Information Age. Abu Dhabi: The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research. [Google Scholar]

- Shishkina, Alisa R., and Leonid M. Issaev. 2015. Internet Censorship in Arab Countries. Aziya i Afrika Segodnya 2: 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, Vernon, and Ben Elgin. 2011. Torture in Bahrain Becomes Routine with Help from Nokia Siemens. Available online: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-08-22/torture-in-bahrain-becomes-routine-with-help-from-nokia-siemens-networking (accessed on 13 September 2018).

- SMEX. 2015. Mapping Blocked Websites in Lebanon 2015. Available online: https://smex.org/mapping-blocked-websites-in-lebanon-2015/ (accessed on 6 November 2018).

- Stepanova, Ekaterina. 2011. The role of information communication technologies in the “Arab spring”. Ponars Eurasia 15: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens-Davidowitz, Seth. 2012. How Racist Are We? Ask Google. The New York Time. June 9. Available online: https://campaignstops.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/06/09/how-racist-are-we-ask-google/ (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Sukhov, Nikolay V. 2013. «Politicheskaya vesna» v Marokko ["Political Spring" in Morocco]. In Sistemnyy Monitoring Global“nykh i Regional”nykh Riskov: Arabskiy mir Posle Arabskoy Vesny. Edited by Andrey V. Korotayev, Leonid M. Issaev and Alisa R. Shishkina. Moscow: Librokom. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhova, Elena F. 2008. Vliyaniye pravitel’stva na deyatel’nost’ arabskikh SMI [The influence of the government on the activities of the Arab media]. Vestnik Nizhegorodskogo Universiteta im. N.I. Lobachevskogo. Seriya: Mezhdunarodnyye Otnosheniya, Politologiya, Regionovedeniya 1: 190–93. [Google Scholar]

- Swigger, Nathaniel. 2013. The online citizen: Is social media changing citizens’ beliefs about democratic values? Political Behavior 35: 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syukiyainen, Leonid R. 2012. Sovremennyye religioznyye kontseptsii prav cheloveka: sopostavleniye teologicheskogo i yuridicheskogo podkhodov [Modern religious concepts of human rights: a comparison of theological and legal approaches]. In Prava Cheloveka Pered Vyzovami XXI Veka. Edited by William V. Smirnov and Alexander Y. Sungurov. Moscow: Rossiyskaya assotsiatsiya politicheskoy nauki (RAPN); Rossiyskaya politicheskaya entsiklopediya (ROSSPEN). [Google Scholar]

- Szajkowski, Bogdan. 2011. Social Media Tools and the Arab Revolts. Alternative Politics 3: 420. [Google Scholar]

- Terrab, Mustafa, Alexandre Serot, and Carlo Rossotto. 2004. Meeting the Competitiveness Challenge in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: The World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research. 2006. Arab Media in the Information Age. Abu Dhabi: The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research. [Google Scholar]

- Tufekci, Zeynep, and Christopher Wilson. 2012. Social media and the decision to participate in political protest: Observations from Tahrir Square. Journal of Communication 62: 363–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN General Assembly. 1948. Plenary Meetings. Official Records. New York: UN General Assembly, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Universal Islamic Declaration of Human Rights. 1981. Paris. Available online: http://www.alhewar.com/ISLAMDECL.html (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Warf, Barney. 2011. Geographies of global Internet censorship. GeoJournal 76: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warf, Barney, and John Grimes. 1997. Counterhegemonic discourses and the Internet. Geographical Review 87: 259–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2012. World Development Indicators Online; Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ (accessed on 9 August 2018).

- Yemen’s Constitution. 1991. San’a. Available online: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Yemen_2001.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2018).

| 1 | One should bear in mind that, despite the fact that in the Arab countries there is ethno-confessional diversity and there are multi-part societies (like Lebanon, for example), Sunni Islam is the dominant religious identity there. |

| 2 | 8000–13,000 USD. |

| 3 | 15,000–150,000 USD. |

| 4 | 500–14,000 USD. |

| 5 | Specifically, the Gaddafi regime in Libya. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shishkina, A.; Issaev, L. Internet Censorship in Arab Countries: Religious and Moral Aspects. Religions 2018, 9, 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9110358

Shishkina A, Issaev L. Internet Censorship in Arab Countries: Religious and Moral Aspects. Religions. 2018; 9(11):358. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9110358

Chicago/Turabian StyleShishkina, Alisa, and Leonid Issaev. 2018. "Internet Censorship in Arab Countries: Religious and Moral Aspects" Religions 9, no. 11: 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9110358

APA StyleShishkina, A., & Issaev, L. (2018). Internet Censorship in Arab Countries: Religious and Moral Aspects. Religions, 9(11), 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9110358