2. The International Panel on Social Progress

The International Panel on Social Progress brought together more than two hundred scholars, from a wide range of disciplines and from many different parts of the world, in order to assess and to synthesize the state-of-the-art knowledge that bears on social progress across a wide range of economic, political and cultural questions.

2 The immediate goal was to provide the target audience (individuals, movements, organizations, politicians, decision-makers and practitioners) with the best expertise that social science can offer on whatever aspect of social progress was under review.

The process—to a significant extent modelled on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—was a long one, leading to publication in 2018.

3 In the final, three volume report, there are two introductory and two concluding chapters. The remaining eighteen are divided into three sections: economic, political and cultural. Unsurprisingly the chapter on religion falls into the last of these categories, along with the material on cultural change, the pluralization of families, global health and the parameters of human living, education and belonging and solidarity. Social progress—the key to the whole enterprise—is defined in Chapter 2. Setting aside Enlightenment assumptions that progress is somehow built into history, the chapter constructs what its authors take to be the most important normative dimensions for making comparisons in this multifaceted arena (over time and between places). These are conceptualized as values (against which to measure progress) and principles (which guide action), mindful that what is considered progress in one context may be differently assessed in another. The notion of a compass is deployed as a metaphor: the map in question is complex and the destination elusive; it is possible nonetheless to set the line of travel.

Early in 2015, I was invited to become a Co-ordinating Lead Author (CLA) for the chapter on religion in the IPSP report. My partner was Nancy Ammerman—a distinguished sociologist of religion from Boston University in the US. Our first task was to build the team, bearing in mind that we needed expertise from different disciplines, different world faiths and different global regions (including East Asia) in order to cover the necessary literature.

4 Above all however we needed hands-on experience in empirical work, in order that our text might be fully grounded in the realities of religion as they exist in different parts of the world. At the same time, we had to find a discourse that related these realities to the concept of social progress as this was understood by the project as a whole. We had moreover to find ways of making this speak to a diverse readership both inside and outside the academy. Every member of the chapter team contributed to this task.

5The first meeting of the IPSP authors (including ourselves) took place in Istanbul in August 2015. It was a learning experience in every sense of the term. Not only was this the first time that the chapter team had come together (some of them travelling many thousands of miles), it was also the moment when we appreciated that significant sections of the social-scientific community were hesitant about the relationship between religion and social progress as we were learning to understand this. This hesitancy took two forms: either religion was irrelevant (i.e., no longer of significance), or it was negatively perceived—in other words necessarily inimical to social progress. The fact that religion was—or more accurately was deemed to be—“back” as a factor in global affairs, was therefore a problem.

6In the 48 h that we spent together, we worked hard on finding ways to counter these at best partial and at worst inaccurate, views starting with a clear definition of religion itself. Escaping the limitations of a purely Western perspective was the first step. We argue that religion is more—much more—than the broad range of institutions and beliefs traditionally recognized by social science; it is rather a very much larger cultural domain that encompasses the beliefs and practice of the vast majority (over 80%) of the world’s population (

Johnson et al. 2016). Religion is a lived, situated and constantly changing reality and has as much to do with navigating everyday life, as it does with the supernatural. It follows that the secular, or secularity, should be considered an equally fluid entity, whose distinction from religion will vary from place to place—a division decided more by the context in question that by pre-determined categories. That said, we recognized that what we term humanity’s “limiting conditions”—death, suffering, injustice—are likely to be confronted and explained in religious terms across a wide range of societies.

From this starting point, we developed our approach to the relationship between religion and social progress. Our task was to scour the available literature in order to document our case. Importantly we began from the belief that neither good nor ill could be assumed from the outset. We had rather to look case by case at different social and cultural domains and in different parts of the world, to see what was happening on the ground. We were well aware that particular forms of religion were perceived negatively, sometimes rightly so. Without doubt religion can take forms which are destructive of people and places. Elsewhere, however, religious individuals and religious communities are manifestly associated with the health and wellbeing of their respective societies—an entirely positive feature.

In order to get a grip on the agenda, we worked “upwards” from the micro to the macro. Specifically, we began with the most intimate of human relationships (i.e., those that relate to gender, sexuality and the family), appreciating that these have been moulded from time immemorial by religious rules, rituals and prohibitions. But here as elsewhere, it is important to set aside an over-simple binary between secular progress and religious reaction—the reality is infinitely more complex. The focus on everyday lived religion was a valuable corrective in this respect. It pointed us to a multi-disciplinary literature which documents the ways in which men, women and young people negotiate their very personal lives. It is clear that they accept some of the limitations that derive from religion but question others and extract from these complex negotiations the means to confront the vicissitudes of life.

The subsequent sections of the IPSP chapter deal with political issues. The first of these addressed the question of diversity—looking: (a) at its shape and forms in the late modern world and (b) at its governance. Both questions were central to the Singapore conference and will be expanded in more detail in the following section of this article.

The second political theme concerned the much talked-of connections between religion and conflict. The core argument is easily stated. To ask whether religion—or certain forms of religion—cause conflict or violence is not the most helpful approach. Much more constructive are enquiries which deploy a social scientific lens to look systematically at the circumstances in which a violent outcome is likely. Contestation over physical spaces is one such, as is an excess of regulation which leads all too often to negative attitudes towards minorities. Even more important is the considerable evidence that weak or failed states (and the fragile economies associated with them) encourage—by default—violent and authoritarian attempts to restore order. Some of these are religiously inspired.

There is however another side to this coin. Clearly there are situations in which religion becomes entangled with violence but it is equally a resource for peace-making. This can be seen in the attention to values (those associated with justice or righteousness) promulgated by all the world faiths; it can also be expressed organizationally. Both dimensions are illustrated in the local and concrete—in for example the sensitive management of particular sacred spaces—and in the expertise of global movements such as the Sant’Egidio Community, the World Council of Churches and (to give but one American example) the Interfaith Dialogue and Peacebuilding Program at the US Institute of Peace. It is equally clear that religious actors are often critical players in post-conflict situations: good examples can be found in South Africa or Northern Ireland.

The relationship between religion and human rights offers a linking theme in this respect. The concept of human rights has become a defining discourse in the management of diversity, in the resolution of conflict and in the fair distribution of resources. Across all of these domains, however, the relationship between religion and human rights is differently regarded: from active advocacy at one end of the spectrum to open hostility at the other. There are those who draw from Article 18 of the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights to uphold the freedom of religion and belief as a fundamental and universally applicable human right; there are others who see the demands of religion and religious people as inimical to an alternative range of freedoms (those, for instance, of free speech, of women and of LGBTi communities). The existence of a UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion and Belief is indicative of a determination to find a way forward not only in places where diverse religious and secular norms are valued but also in places where they are likely to come into conflict—gender-specific abuses being a case in point.

There are two further substantive sections in the IPSP chapter. The first reflects an additional theme in the EASSSR conference in that it deals with the place of religion in the wellbeing of individuals and communities. Particular attention is paid to welfare, education and healthcare. A striking example will be taken to illustrate the approach. Faced with the seeming impasse between secular health professionals and faith-based initiatives in parts of the developing world, a series of contributions in

The Lancet offers an evidenced-based way forward.

7 The emphasis is on partnership, arguing that secular and faith-based organizations can work together even when there are areas of disagreement regarding policy and practice. The crucial point is to ascertain exactly what these are—and thus to establish not only what cannot be done in partnership but the (normally much greater) areas of work that can be shared. The need is such that it is unwise to rule out significant resources on principle. Not all partnerships with religious organizations are advisable but many are.

One further area requires attention—that is the role of faith-based organizations in caring for the earth itself (the final step in our ascending scale). Unsurprisingly given its genesis, a number of chapters in the IPSP report engage growing concerns about the environment and the role of social science—as well as natural science—in understanding these better. Our task was more specific: namely to draw attention to the place of religious groups in this enterprise. Again, a single example captures the potential.

Laudato Si’—the second encyclical of Pope Francis—was published in 2015. It is regarded as a landmark moment in the debate surrounding ecological issues. It is not only the size of the Pope’s constituency that counts (though that most certainly matters) but the fact that he draws on established research to deliver a powerful ethical message: that deprived communities will suffer most from climate change. Taking both these points together, there can be no doubt that the Pope has vastly extended not only the reach but the impact of the debate—a fact recognised as much by scientists as by theologians.

8The final part of the chapter is constructed differently. It takes the form of an action toolkit deriving from a set of cross-cutting themes that run right through our material. These include: the

persistence of religion in the modern world, in the sense that it is neither vanishing nor resurgent; the importance of context in discerning outcomes (both positive and negative); the urgent need to enhance cultural competence (not least religious literacy) in different parts of the world; the significance of religion in initiating change; and the gains that accrue from effective partnerships. In short: “…researchers and policy-makers pursuing social progress will benefit from careful attention to the power of religious ideas to motivate, of religious practices to shape ways of life, of religious communities to mobilize and extend the reach of social changes and of religious leaders and symbols to legitimate calls to action” (

International Panel on Social Progress 2018, p. 643).

3. Managing Global Diversity

Rightly the inaugural conference of the EASSSR paid particular attention to the presence of religious diversity in East Asia, seeing this as the result of two things: first, population movements both within and the beyond the region; and second, shifts in government policies. Both causes and consequences were explored in a wide variety of papers. It was, moreover, significant that the conference was held in Singapore—one of the most religiously diverse places in the modern world.

9Religious diversity was an equally central theme in our IPSP work, as we sought both to document and to explain the capacities (or not) of diverse populations to live alongside one other in different parts of the world. Our first task, however, was to untangle a tricky vocabulary and to underline the difference between diversity (which is a descriptive term) and pluralism (which is normative and implies judgments about diversity)—a distinction which is not always recognized in the literature (

Beckford 2003). We also needed to establish the facts and figures in different global regions, mindful that it is not necessarily the case that diversity is increasing in the modern world. Establishing whether or not this is happening is an empirical rather than an a priori question.

For example, it is most certainly the case that religious diversity is growing in Western Europe (

Figure 1),

10 a fact with huge implications both for religion as such and for the theories that we deploy to understand this (see

Section 4). This is much less the case further East, that is, in post-communist Europe (

Figure 2), where the historic churches are becoming noticeably more assertive, often at the expense of religious minorities, both Christian and other. In this part of Europe, the fall of communism (in 1989) marked a watershed, bringing to an end a prolonged period of politically enforced secularization. To an extent a similar shift has taken place in China following the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) but here there has been a marked growth both in religion per se and in religious diversity (

Figure 3), prompting a key theme in the EASSSR conference program and an excellent IPSP case study.

11 The future, however, remains uncertain.

Religious diversity can also flat line as is the case in South East Asia (

Figure 4), a region where diversities of all kinds should be seen as “constitutive.” Singapore offers an excellent example, providing the IPSP chapter team with a further instructive case study.

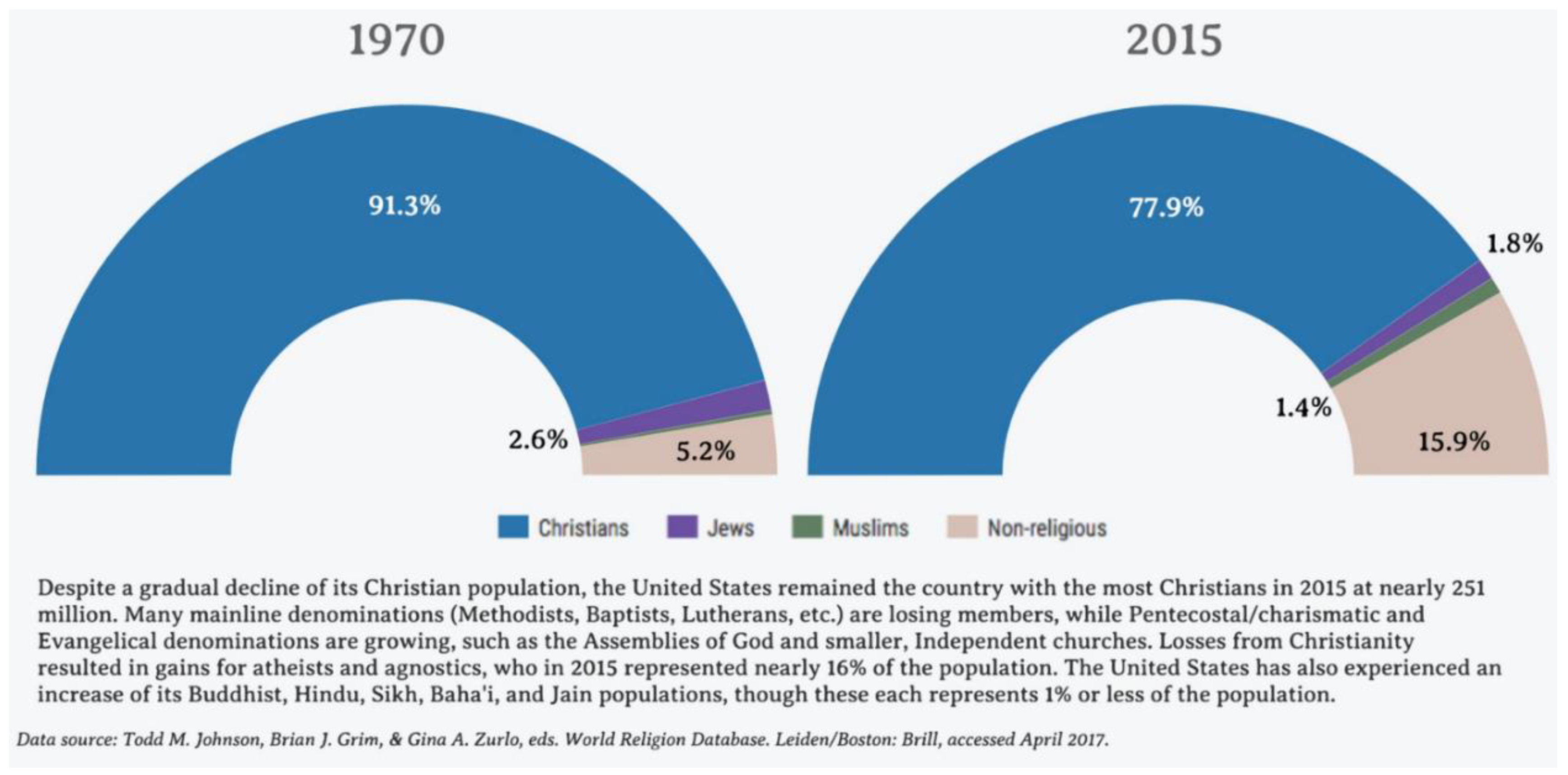

12 Such flat-lining can also be found in the US (

Figure 5), though here the never-ending choices lie almost entirely

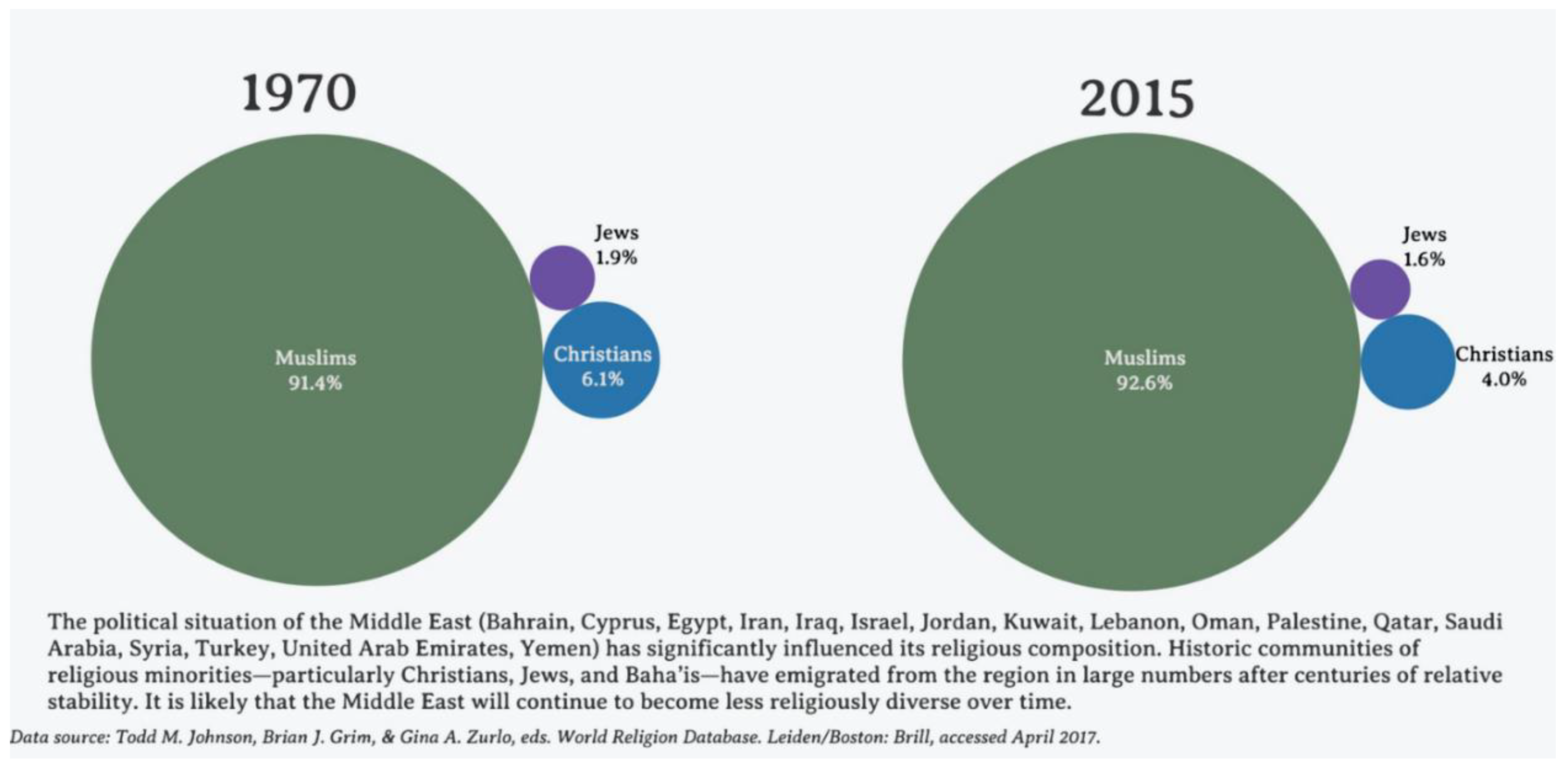

within Christianity rather than beyond it. Diversity, finally, can and does diminish but for different reasons in different places. One reason, sadly, is conflict, as in the seemingly unresolvable situation in the Middle East where large numbers of both Jews and Christians see no alternative but to leave, after centuries of continuous presence (

Figure 6).

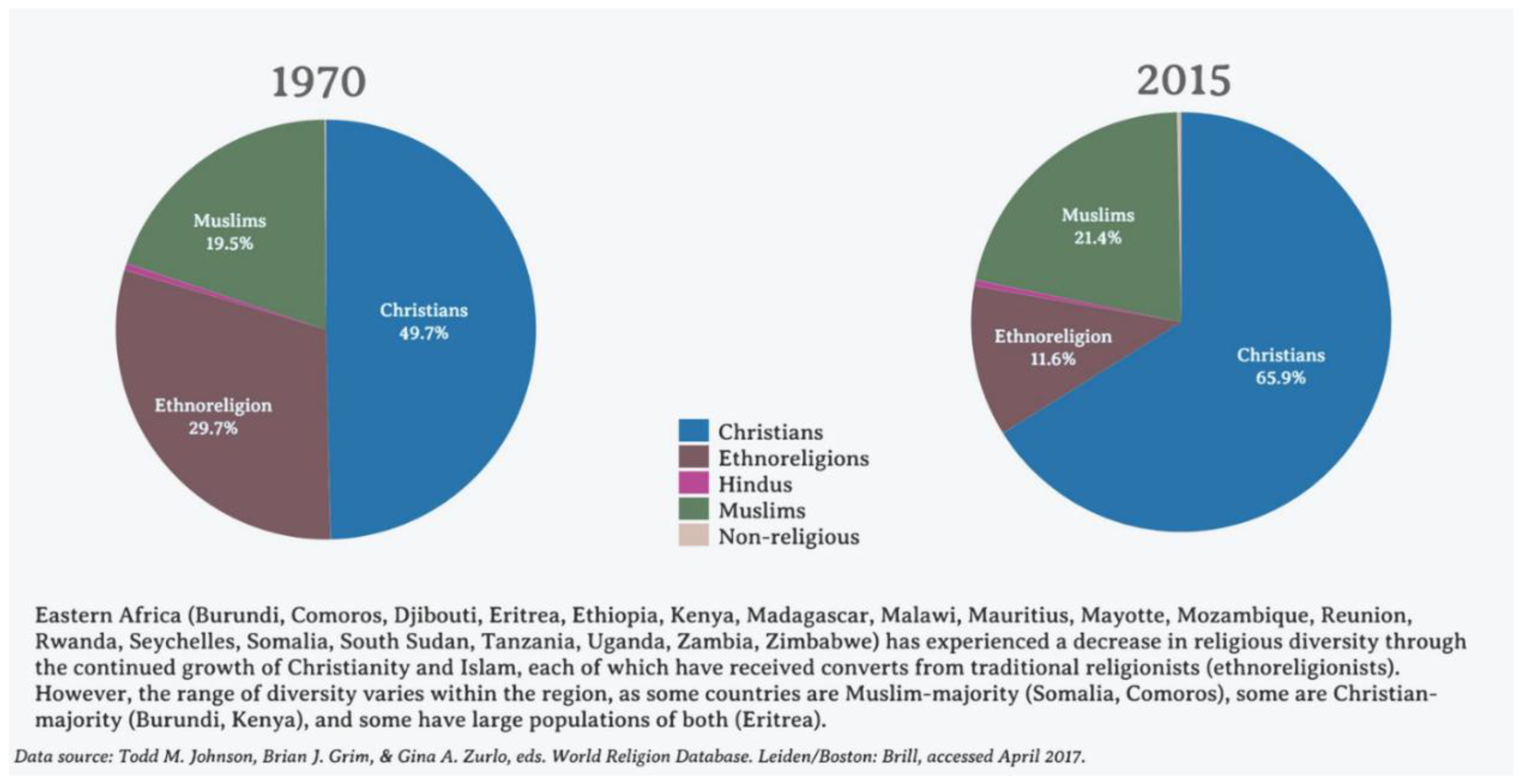

13 In parts of Africa an entirely different process is taking place in countries where the gradual ascendancy of world faiths, notably Christianity and Islam, has emerged at the expense of multiple indigenous religions (

Figure 7).

In short, the picture is complex; so also are the questions that follow. A constructive starting point lies in the recognition that religious diversity is part and parcel of a broader agenda but that it has particular characteristics. Religious differences, for example, are likely to strike more foundational chords than variations in taste or style—quite simply there is more at stake. Equally central is an awareness that diversities exist, largely (if not exclusively) because of the movement of people, both forced and unforced. The interrelationships of religion and migration become therefore a central theme. They run, moreover, in different directions. On the one hand, religions inspire, manage and benefit from the migration process but on the other, they are shaped and moulded by the dislocations of populations that inevitably ensue. You cannot have one without the other.

The consequences require careful management: migration is a hot political issue. For which reason, we reflected carefully on the various forms of governance discovered in this field and the debates that surround them. These include the pros and cons of multiculturalism, of diverse forms of secularism and of democracy itself. We recognized, however, that there are deeper questions to address: those that probe the ways in which religiously diverse people do not simply co-exist but flourish in each other’s company. We discovered, for example, that “street level ecumenism” (working side by side) is often more effective than a dialogue between elites.

14 Such an approach drives us back once again to the realities of lived religion in addition to its official formulations.

One final point concludes this section: that is to appreciate that the concept of diversity as such is far from uniform and means different things in different places. The significance of this fact for the understanding of religious life is nicely captured in the following paragraphs, taken from a relatively recent essay by

Martin (

2013). The focus of the essay is the global spread of Pentecostalism (an example of transnational voluntarism); the implications, however, are far-reaching:

“The big contrast on the global scale is between transnational voluntarism and those forms of religion based on a closed market, which regard certain territories as their peculiar and sacred preserve and assume an isomorphic relation between kin, ethnicity and faith. The principle of the transnational voluntary organisation competes globally with the religions of place and ethnicity…The global variations run along a scale from North America, where it [the exercise of choice] is normal, to Western Europe and Australasia, where it is accepted but not all that frequent, to the Arabian Peninsula, which is by definition Islamic territory where even foreigners cannot establish their own sacred buildings”.

In short, diversity is taken for granted in the US and is becoming more so in Western Europe. In East Europe—where ethnicity and religion significantly overlap—a different pattern has emerged (see above). What Martin terms “Islamic territory” lies at the opposite extreme to the US. Here diversity is barely permitted and acquires therefore an entirely different meaning. Not all Muslims, however, live in Muslim territories: in the global East, for example, they constitute one minority among others, as they do in Western Europe. The evolving situation in Europe provides the link to the following section.

4. Thinking Theoretically about Global Religious Diversity

Two points come together in this discussion: the first describes the origins of the social sciences (specifically sociology) in the European Enlightenment; the second reflects on the consequences of this situation for the understanding of religion in the modern world, starting with the changing situation in Europe itself before returning—step by step—to the global East.

Correctly sociology has been described as the “epistemological child of the Enlightenment” and like the Enlightenment thinkers themselves, “early sociologists saw rationality and empirical observation as the ultimate source of knowledge” (

Spickard 2017, p. 48). For this reason, sociology finds its disciplinary identity in its opposition to religion. And once religion and still more theology, is cast as sociology’s “other”, it follows that the notion of secularization, as the concomitant of modernization (and thus progress), is built into the DNA of the discipline. The story is a French one, in which the Enlightenment takes a markedly anti-religious turn, squaring off against an equally intransigent Catholic Church. This—it should be noted—is much less the case in Protestant Europe and by the time that Enlightenment ideas cross the Atlantic, the core notion of a “freedom from belief” (meaning freedom from the dominance of the Catholic Church), mutates into a “freedom to believe”—a noticeably different formulation (

Himmelfarb 2004).

These variations on the theme are important but the crucial point endures. Sociology and the social sciences more generally, developed their disciplinary self-understanding in a specific intellectual environment—one, moreover, which has been formative in European culture.

Does this matter? Does it matter, in other words, that these disciplines emerge from a distinctive environment and are necessarily coloured by this? We must answer this question in stages, looking first at the situation in Europe. The starting point is clear: in most parts of the continent, the relatively good fit between what might be termed “traditional” understandings of sociological theory and empirical realities remains intact, keeping in mind regional variations, growing complexities and unexpected developments. Undeniably, the dominant trend towards greater secularity continues, noting that the

process of secularization takes place very differently in different European societies.

15That however is not the whole story. In my own work (

Davie 2006,

2015) I have discerned five very different factors that must be taken into account if we are to understand fully the present situation in Western Europe. These are: the centrality of the Judaeo-Christian tradition in Europe’s cultural heritage; the continuing—if diminished—significance of Europe’s historic churches which work on the principle of a public utility (i.e., they are there at the point of need for anyone who lives in a designated place); a growing number of alternatives to these churches which, taken together, look more like a market than a public utility; a marked influx of new arrivals since 1945 who come from many parts of the world and bring with them a wide variety of world faiths (among them are Christians, Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs and Buddhists); and finally a noticeable growth in the numbers of people who describe themselves as “nones”—that is, as having no religion.

More—much more—could be said about all of these factors but the crucial point to note is that they push and pull in different directions to produce the following, largely unexpected, paradox. At one and the same time European populations are becoming both more secular and more religiously diverse. The former is closely associated with the privatization of belief, a trend in line with classic understandings of secularization. The latter does the reverse: it enhances the public profile of religion not least in public debate. Put succinctly: Europeans talk more about something that they do less. The consequence, all too often, is an ill-informed and ill-mannered conversation about matters of extreme importance to the functioning of a healthy democracy. The catalysts for these debates vary depending on the country under review. In France for example they are dominated by (mostly Muslim) dress codes; in Britain or Denmark, freedom of speech—including the freedom to insult a religious minority—is more prominent. That said, the underlying question remains the same: how do Europeans, who have shared up to two millennia of Christian history, learn to accommodate minorities whose religious aspirations are coloured by very different cultural backgrounds and are likely to manifest themselves in unexpected ways—in public and well as private life.

A second, rather more searching, question cannot be avoided. It is easily articulated: is Europe secular because it is modern, or is Europe secular because it is European? Expressed thus, the question opens up the relationship between modernization and secularization. Is it the case that modernization necessarily brings about secularization, or does this only happen in particular—i.e., European—circumstances? One way of responding is to reverse the line of argument: in other words, to ask not what Europe is but what Europe is not. Following the examples that I used in a book which explored this theme is some detail (

Davie 2002), the answer is clear. Europe is not (yet) a vibrant religious market such as that found in the United States; it is not a part of the world where Christianity is growing exponentially, very often in Pentecostal forms, as is the case in the global south; it is not a part of the world dominated by faiths other than Christian but is increasingly penetrated by these; and it is not for the most part subject to the violence often associated with religion and religious differences in other parts of the globe—the more so if religion becomes entangled in political conflict. Hence the inevitable, if at times disturbing (for some) conclusion: that the patterns of religion in modern Europe, including its relative secularity, might be an exceptional case in global terms. A rather similar conclusion emerges from a second publication, which developed the comparison between Europe and the US in more detail (

Berger, Davie and Fokas 2008).

The corollary in terms of the argument of this article is clear. The theoretical corpus of mainstream social science has been honed, in what has turned out to be the atypical case with respect to global patterns of religiousness, for which reason universalizing the theory really does cause trouble. That was so in our initial encounters with the IPSP project, where our colleagues had considerable difficulty in seeing the significance of religion for the topic under review; it is equally likely to be the case in East Asia.

A book that not only captures the significance of this statement but relates it at least in part to the East Asian situation was published in the spring of 2013. Christian Caryl’s Strange Rebels weaves together a complex narrative which involves four protagonists and five countries and finds its focus in a series of changes that take place in 1979. The protagonists are Mrs. Thatcher, Deng Xiaoping, the Ayatollah Homeini and Pope John Paul II. The five countries are the United Kingdom, China, Iran, its neighbour Afghanistan and Poland, then part of the Eastern bloc. Mrs. Thatcher and Deng initiated market reforms challenging deeply held assumptions about the way to manage the economy. The Ayatollah and John Paul II, conversely, were motivated by their respective religions to challenge the hegemony of the secular (socialist) state. In Afghanistan, Islamism became a major factor in the resistance to the Soviet Union, as did Catholicism in Poland.

The imaginative leap in Caryl’s analysis is to draw these factors together:

“The forces unleashed in 1979 marked the beginning of the end of the great socialist utopias that had dominated so much of the twentieth century. These five stories—the Iranian Revolution, the start of the Afghan jihad, Thatcher’s election victory, the pope’s first Polish pilgrimage and the launch of China’s economic reforms—deflected the course of history in a radically new direction. It was in 1979 that the twin forces of the markets and religion, discounted for so long, came back with a vengeance”.

The “victims” in this particular scenario were the dominant ideologies of the twentieth century embodied in the secular state, in either its socialist or communist forms. Both adjective (secular) and noun (state) are important in a formulation which was seen as the lynch pin of modernization. To be modern meant to be secular and the accepted form of political organization was the state. The “new” combination of market and religion not only erodes both elements but reveals the connections between 1979 and 1989 and in the fullness of time 2001. By 1989 the market had proved itself more effective than the command economy of the Soviet Union and religion—whether in its Muslim or Christian forms—was clearly more durable than its secular equivalent, in this case communism. Forces set in motion in 1979 led inexorably to the fall of the Berlin wall just over ten years later and the collapse of the Soviet Union overall led in turn to a radical realignment of the global order which—to an extent—is still in train.

16 The attack on the Twin Towers in 2001 is not covered in Caryl’s account but the connections are clear enough. Quite clearly Islamism is one factor among others behind this epochal moment, to the evident bewilderment of the West.

It is important to remember that Caryl is writing some thirty years after the event and can make connections that were not at all clear at the time. Indeed, for those involved the principal feature that linked these three world-changing events was their unexpectedness. Manifestly, both policy-makers and pundits were caught unawares—in every case. Why was it that the Shah of Iran, a western figurehead, was obliged to flee before an Ayatollah motivated by conservative readings of Islam? And why did observers of all kinds fail to anticipate the concatenation of events that led to the fall of the Berlin wall and the collapse of communism as a credible narrative? And why finally did the events of 9/11 come like a bolt from the blue? By this stage there was a growing awareness of events in the Muslim world and their significance for Western policy,

17 but nobody—nobody at all—expected hi-jacked planes to fly into iconic buildings in New York. Hence the abruptness of the wake-up call: religion was undeniably important in that it was clearly able to motivate widely different groups of people to act in dramatic and unforeseen ways—a realization that prompted renewed attention to an aspect of society that had been ignored for too long.

All too often, however, the wrong inference was drawn. Commentators were rather too ready to assume that religion was resurgent or back, reasoning that we are now in a post-secular, rather than a post-religious, situation. To argue thus, however, is to conflate two rather different things. Was it really the case that religion (or God) was back? Or was it simply that the disciplines of social science in the west, along with a wide variety of politicians and policy-makers, had become aware (or re-aware) of something that had been there all the time? Was it, in other words, perceptions that had altered rather than reality? It is, I think, a complex mixture of both. New forms of religion have asserted themselves in different parts of the world; that is beyond doubt. It is incorrect to assume, however, that the new manifestations emerged from a vacuum. What is—or has been—lacking, however, is a social-scientific narrative that is fit for purpose: one in other words that is sensitive to the religious factor in all its manifest diversity but which sees this not as an aberration but as an entirely “normal” element in late modern, twenty-first century life.