Abstract

A large literature on feminist theology and philosophy of religion has explored the various ways in which feminism has reshaped religious thought and practice within different faith traditions. This study uses Festinger’s (1965) cognitive dissonance theory and the 2017 Nishma Research Survey of American Modern Orthodox Jews to examine the effect of tension between feminism and Orthodox Judaism on lay men and women. For 14% of Modern Orthodox Jews, issues related to women or women’s roles are what cause them “the most pain or unhappiness” as Orthodox Jews. The paper examines the sociodemographic characteristics associated with this response and tests whether those who experience this cognitive dissonance are more likely to (1) advocate for changes in the role of women within Orthodox Judaism and/or (2) experience religious doubt. The analysis reveals that these individuals overwhelmingly take a feminist stance on issues related to women’s roles in Orthodox Judaism, and they also manifest more religious doubt. The paper discusses the dual potential of cognitive dissonance to either spur changes in women’s religious roles in traditional religious communities and/or threaten the demographic vitality of those communities.

1. Introduction

A growing literature on feminist theology and philosophy of religion has documented the ways in which sexism is being redressed in religious teachings and institutions. This paper focuses on how lay people confront the tension between feminist and religious commitments. Using the idea of cognitive dissonance, this study explores how men and women within one conservative religious tradition—namely, Orthodox Judaism—understand and respond to feminist challenges. Following existing research, it tests whether Orthodox Jews who experience cognitive dissonance as a result of their religious and feminist commitments will be more likely to (1) advocate for changes in the role of women within Orthodox Judaism and/or (2) experience religious doubt.

1.1. Cognitive Dissonance and Religious Change

Cognitive dissonance is the idea that people experience psychological discomfort when there is inconsistency among their beliefs, or inconsistency between their beliefs and their actions (Festinger 1965). Similarly, self-concept discrepancy theory holds that inconsistency between an individual’s “actual” versus “ideal” or “ought” selves leads to psychic discomfort (Higgins et al. 1985). In order to relieve this discomfort, people (1) try reduce dissonance by changing their beliefs, actions or environments and (2) avoid situations and information that accentuate or increase the dissonance.

Cognitive dissonance has been widely used to explain religious change, on the individual and group levels. Festinger’s (1956) classic study of a doomsday cult was one of the first to demonstrate that, when presented with the cognitive dissonance of disconfirmed expectations, individuals often rationalize and intensify their beliefs rather than abandon them. Subsequent experiments confirmed this tendency with respect to religious beliefs (Batson 1975; Burris et al. 1997). The idea of cognitive dissonance has also been used to explain why groups who are marginalized within a given religious community may change their religious beliefs. For example, lesbian Christians in anti-gay religious environments may choose to abandon the church or disregard the portions of Scripture that are disparaging (Mahaffy 1996; Thumma 1991).

1.2. Religion and Feminism

Many scholars have acknowledged a tension between feminism and religion. To varying degrees, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Taoism and Confucianism all manifest sexist teachings and institutions, such as holding that men are spiritually superior to women, giving men more authority and prestige than women and identifying the divine as male (Gross 1996; Paludi 2016). Beginning in the 1960s, academics, theologians and philosophers of religion started developing feminist theologies and philosophies of religion to address these inequities (see, e.g., Anderson 1998; Anderson and Clack 2003; Jantzen 1999; Parsons 2002). Religious feminist leaders within many different faith traditions attempted to bring women’s experiences to bear on the interpretation of sacred texts, liturgical language and ritual, and to increase the presence of women in religious leadership (Braude 2004; Weaver 1995).

Outside of these elite circles, how does feminist consciousness penetrate and affect the lives of religious individuals? As Davidman (2000, p. 524) pointed out, understanding how individuals reconcile religion and feminism requires knowing “just how it is that feminism comes to be situated as a force that conservative religious groups must contend with.” Manning (1999) suggested that education is key: support for feminism is correlated with educational attainment. Other research has pointed to labor force participation: while unpaid labor in the home finds affirmation and legitimation from traditional forms of religion, labor force participation exposes women to egalitarian ideas that can challenge traditional religious beliefs (Schnabel 2016; Woodhead 2008). Empirically, being in the labor force and having higher earnings are associated with lower levels of religiosity among women (Pew Research Center 2016; Schnabel 2016).

What type of feminism penetrates and affect the lives of religious individuals? Is it the classical liberal feminism that was mainstream among US feminists in the 1960s and 1970s, which asserts that women and men deserve equal opportunity to succeed in the public sphere and seeks to dismantle systematic, sex-based advantages (Tong and Botts 2017)? Is it a feminism that responds to the critiques of liberal feminism that arose in the 1980s, one that focuses on women’s differences and recognizes that multiple forms of oppression, including racism and classism, operate alongside sexism (Collins 1990; Hooks 1981)? Crenshaw (1989) coined the term “intersectionality” to describe how multiple forms of oppression reinforce one another, and subsequent feminist scholarship has focused extensively on diversity among women and their multiple experiences of oppression (Davis 2008). At the same time, liberal feminist ideas are still widely circulated outside the academy (Kinahan 2004).

A number of ethnographic and interview studies have explored how women, particularly those in conservative religious communities, understand and respond to gender inequality within their religious traditions (Beaman 2001; Brasher 1998; Davidman 1991; Ecklund 2003; Griffith 1997; Hartman Halbertal 2002; Ingersoll 2003; D. R. Kaufman 1991; Manning 1999; Ozorak 1996; Rose 1987; Stacey and Gerard 1990; Stocks 1998; Zimmerman 2015). Few of these studies articulate how the research participants or the researcher define feminism. One exception is Manning (1999), who concluded that Evangelical, conservative Catholic and Orthodox Jewish women understand feminism as liberal feminism. Other research provides implicit support for this conclusion, as the women focus on liberal feminist issues of systematic, sex-based discrimination, such as prohibitions against women being clergy (e.g., Beaman 2001; Stacey and Gerard 1990). Only Zimmerman (2015) frames her research in terms of intersectionality, arguing that Muslim women’s decision to wear the hijab is affected by nation, colonialism, sexuality, class, religion, age and ability.1

Regardless of how feminism is defined, empirical findings support the idea that individuals experience cognitive dissonance in trying to hold both religious and feminist beliefs. Data from the General Social Survey was used to demonstrate that feminist churchgoers feel less close to God than non-feminist churchgoers (Steiner-Aeschliman and Mauss 1996). The ethnographic and interview studies cited above uncovered a wide range of responses to this tension:

- Avoiding distress by focusing on other aspects of religious life;

- Justifying distinct gender roles as natural and beneficial;

- Reframing gendered religious practices as manifestations of women’s empowerment;

- Pursuing alternative modes of power within their religious communities, such as women’s ministry programs, that do not threaten male dominance;

- Advocating for religious change, such as women in religious leadership roles and gender-inclusive language about God; and

- Switching to a more liberal religious community or abandoning religion altogether.

While uncovering the range and complexity in how religious women respond to the cognitive dissonance that stems from competing religious and feminist ideas, these studies also raised several new questions. How do religious individuals relate to the ideas of liberal feminism versus intersectional feminism? How does feminist consciousness penetrate religious communities in the first place? How strong is the influence of cognitive dissonance on individuals’ likelihood of changing their religious beliefs? This paper will examine these questions with reference to one conservative US religious group: Orthodox Jews.

1.3. The Case of Orthodox Jews

This study examines the conflict between feminism and religion among Orthodox Jews. Orthodox Judaism is, in general, the most conservative of the Jewish religious movements, asserting that Jews have a divine obligation to follow the laws of the Torah as understood by Jewish rabbinic tradition. In a contemporary American context, scholars and lay people alike distinguish between “Modern Orthodox” Jews, who attempt to maintain Jewish law while also engaging with modern, secular knowledge, and more right-wing Orthodox Jews, who attempt to separate themselves from the secular world (Fishman 2007). About 10% of all US Jewish adults identify as Orthodox, and about one third of those identify as Modern Orthodox (Pew Research Center 2013).

Several feminist scholars have laid out the specific conflicts between Orthodox Judaism and feminism (Greenberg 1981; Hartman 2007; Ross 2004, 2000).2 Men and women are not equal under Orthodox Jewish law, and only men serve as Jewish legal decisors; furthermore, women have more limited opportunities to engage in traditional Jewish learning or serve in leadership roles. One particular aspect of Orthodox Jewish law has become a lightning rod for feminist criticism: the fact that men must actively grant a divorce, leaving some women as agunot (“chained wives”) if their husbands disappear or refuse to grant them a divorce (Hacohen 2004). Fishman (1993, p. 159) described Orthodox Jewish feminists as “psychologically split at the root” due to the difficulty of reconciling feminism with an androcentric religious tradition.

Some Orthodox Jewish leaders have responded to feminist critiques with apologetic reasoning for the existing norms, arguing that gender roles within traditional Judaism reflect innate, biological differences between men and women (M. Kaufman 1993). At the same time, methods for minimizing gender inequities have also developed: more flexible interpretations of existing norms, legal workarounds to subvert sexist practices and rituals centered on the religious experiences of girls and women. For example, many Orthodox Jewish communities have adopted bat mitzvah ceremonies for girls and women’s prayer groups (Fishman 1993; Uzan 2016). Orthodox “partnership” prayer groups wherein women are included more broadly in ritual leadership have appeared across Israel and North America (Sztokman 2011; Uzan 2016). Women have also entered into Orthodox Jewish legal discourse through the creation of new positions like yoetzet halakhah, female Jewish legal advisor, and toenet rabbanit, female rabbinical court advocate (Roness 2013; Shamir et al. 1997). These and other efforts to maximize meaningful participation and equality for women within Orthodox Judaism have been highly controversial.

Ross (2000) claimed that, as many Orthodox Jews have adopted mainstream, Western, gender egalitarian views, the status of women has become the single greatest challenge to the future of Orthodoxy. There is little systematic data to either support or challenge this assertion. Two ethnographic studies found that newly Orthodox Jewish women did not identify as feminists, nor did they challenge gender inequities within Orthodoxy; instead, they lauded Orthodoxy for honoring women’s roles as wives and mothers, for holding men accountable to women and for valorizing “feminine” values like nurturance (Davidman 1991; D. R. Kaufman 1991). Yet, these two studies focused exclusively on the subset of Orthodox Jewish women who became Orthodox as adults. In contrast, Hartman Halbertal’s (2002, p. 154) qualitative interview study demonstrated the “genuine and painful ambivalence or multivalence” of mothers who are both Orthodox Jewish feminists and religious educators, but these women reflected a religiously educated elite. Only Fishman’s (2000) qualitative interview study captured the attitudes of typical Orthodox women. Some women articulated that the sharp contrast between their professional advancement and their secondary roles in the synagogue created “psychic discomfort” or “dissonance,” which sometimes led them to agitate for change within their communities (Fishman 2000, p. 34).

1.4. Research Questions

The present study begins by examining how Modern Orthodox Jews in the United States who experience cognitive dissonance as a result of their commitment to Orthodoxy and feminism describe their experiences. It then identifies the sociodemographic characteristics associated with experiencing that cognitive dissonance. Unlike previous studies, this study includes women and men, and sex is included as a predictor in the analysis. This study then asks whether cognitive dissonance is leading individuals to (1) advocate for changes in the role of women within Orthodox Judaism and/or (2) reject Orthodox Jewish beliefs. Because this is a quantitative study, it is also possible to estimate the magnitude of the influence of cognitive dissonance on these two outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

This study uses data from the 2017 Nishma Research Survey of American Modern Orthodox Jews. The data and their limitations are described in detail below. The analysis consisted of three phases. First, responses to open-ended questions were used to identify respondents who were experiencing cognitive dissonance as a result of their religious and feminist commitments, and logistic regression was used to determine the sociodemographic characteristics of those respondents. Second, latent class analysis was used to identify respondents’ stances toward the role of women in Orthodox Judaism, and this stance was modelled as a function of experiencing cognitive dissonance and other sociodemographic factors. Third, an index of core Orthodox Jewish beliefs was modelled as a function of experiencing cognitive dissonance and other sociodemographic factors.

2.1. Data

The 2017 Nishma Research Survey of American Modern Orthodox Jews was a project of Nishma Research, a private research firm specializing in the Jewish community. The survey was sponsored by the Micah Foundation, a 501(c)(3) charitable organization whose mission is to promote and enhance Jewish religious and cultural life. The target population for the survey was self-identified Modern Orthodox Jewish adults living in the United States. Data were collected through a web-based, opt-in survey. The Rabbinical Council of America, the main professional rabbinical association for American Modern Orthodox rabbis, distributed the link to the survey to its member rabbis (~1000) and asked them to share the link with their congregants. The survey was available from 27 June 2017 to 31 August 2017. After eliminating responses from individuals who did not identify as Modern Orthodox or did not live in the United States, the total number of complete responses was 2688. Response rates cannot be calculated because neither the size of the target population nor the proportion of the target population that saw the link is known. Due to the lack of precise, reliable demographic information on the target population, data were not weighted. The survey instrument is publicly available from Nishma Research (2017).

There are several limitations to the Nishma survey data. The first relates to the non-independence of the observations. Because the survey was initially distributed by congregational rabbis, respondents were clustered within congregations; and because spouses were encouraged to take the survey separately, some respondents may be clustered within households. Members of the same congregation or household cannot be identified. All the analytic techniques used here (e.g., logistic regression, Latent Class Analysis) assume independence of observations. The clustering of observations may bias the reported p-values.

The second limitation is representativeness. Table 1 compares the Nishma survey respondents to US Modern Orthodox Jewish adults using data from the Pew Research Center’s (2013) Survey of US Jews. The estimates from the Pew Research Center survey are imprecise, but it appears that the age and gender profile of the Nishma survey respondents was roughly consistent with the target population, as was the proportion raised Orthodox.3 However, the Nishma survey respondents were more likely than the target population to be married and to have graduate degrees. In order to address response bias, analyses will include all these sociodemographic variables as covariates. The relationships between variables, rather than point estimates, are key to the present analysis.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of sample.

Other limitations relate to the fact that that the survey was not designed to examine cognitive dissonance related to the conflict between feminism and Orthodoxy, and the present analysis was retrofitted to the data. The survey did not contain any items related to secular feminism, precluding any analysis of how secular feminist beliefs (as opposed to religious beliefs) are influenced by cognitive dissonance. Furthermore, the study’s target population included only current Modern Orthodox Jews, meaning that individuals for whom cognitive dissonance related to feminism and Orthodoxy prompted them to abandon their Modern Orthodox identification are out-of-frame.

2.2. Identifying Cognitive Dissonance and Its Correlates

The first step in the analysis was to determine which respondents were experiencing cognitive dissonance as a result of their religious and feminist commitments. Toward the end of the survey, respondents were told, “Thank you so much for taking this survey. We’re up to the final two questions dealing with your views on Judaism. These questions are open-ended so please tell us as much as you like; we would really love to hear a bit more of your key thoughts.” Respondents were then presented with two open-ended questions:

- “First, what gives the most satisfaction, joy or meaning to your life as an Orthodox/Observant Jew?”

- “And … what, if anything, causes you the most pain or unhappiness as an Orthodox/Observant Jew?”

Seventy-four percent of respondents (N = 1989) provided answers to these questions. Respondents who mentioned any issue relating to women or women’s roles in Orthodoxy as a cause of pain or unhappiness were coded as experiencing cognitive dissonance as a result of their religious and feminist commitments. 4 The content of the answers was analyzed to identify the locus of concern as well as how respondents understood feminism, whether in a liberal feminist frame or through intersectionality. Then, in order to understand the sociodemographic characteristics of Modern Orthodox Jews who experienced cognitive dissonance related to these issues, the binary variable was modelled as a function of the variables in Table 1.

2.3. Identifying Orthodox Feminist Stance and Its Correlates

The second step in the analysis was to identify the stance toward Orthodox feminism of individuals in the sample. This was accomplished using Latent Class Analysis (LCA), a type of measurement model that was developed to identify a latent categorical variable using a set of observed variables, and then categorize observations into classes using the observed variables (Lazarsfeld and Henry 1968). Many types of observed variables (binary, ordinal, nominal, count, and continuous) can be used. In this case, 14 survey items related to attitudes toward women’s roles in Orthodox Judaism were used to identify a latent categorical variable measuring Orthodox feminist stance (Table 2). Responses were recoded into two or three categories.

Table 2.

Observed variables for latent class analysis.

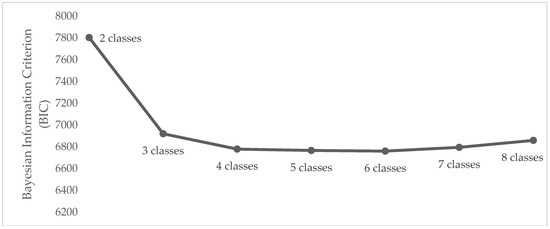

LCA was implemented using a Stata plugin (Lanza et al. 2015). Because LCA requires a decision regarding the number of latent classes to fit, models with successively larger numbers of classes were fitted, and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) was used to determine which model to use (see Nylund et al. 2007). As shown in the scree chart of the BIC for each latent class model (Figure 1), a four-class solution was parsimonious and had good fit-values.

Figure 1.

Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for latent class models.

Respondents were assigned to a latent class based on posterior probabilities (i.e., maximum-probability assignment). In order to understand the role cognitive dissonance in Orthodox feminist stance, latent class was then modelled as a function of the binary cognitive dissonance variable and the sociodemographic variables in Table 1.

2.4. Identifying Orthodox Jewish Beliefs and Their Correlates

An index of Orthodox Jewish beliefs was created by summing across the five survey items shown in Table 3. The index was found to be highly reliable (α = 0.90), with a range of 0 to 10 and a mean of 6.7. In order to understand the role of cognitive dissonance in Orthodox Jewish beliefs, the index was modelled as a function of the binary cognitive dissonance variable and the sociodemographic variables in Table 1.

Table 3.

Items in index of Orthodox Jewish beliefs.

3. Results

3.1. Cognitive Dissonance

Are US Modern Orthodox Jews experiencing cognitive dissonance as a result of their commitment to both Orthodoxy and feminism? Fourteen percent of respondents (N = 281) mentioned an issue relating to women or women’s roles in Orthodoxy as a cause of pain or unhappiness. A few of these respondents explicitly mentioned the contrast between women’s roles in secular society and women’s roles in Orthodoxy:

- “Being completely sidelined because I’m a woman. Main tasks are cooking for Shabbat and yom tov [holidays] with no meaningful engagement. I am a working mom and lawyer. But I am relegated to the kitchen.”

- “The inconsistency of women achieving great feats in the secular world but their Jewish experience kept at a 2nd grade level.”

- “The unequal status of men and women—very hard to justify to my daughter as everything is so equal elsewhere in or lives. Going to lose our youth, who won’t accept it!”

Among the respondents who were coded as experiencing cognitive dissonance, most of their comments concerned the fact that women’s roles and men’s roles are not equal within Orthodox Judaism. Issues mentioned by at least 25 respondents, in descending order of frequency, were:

- Women being unequal or undervalued in Orthodoxy in general;

- Gender inequities in the process of Orthodox Jewish religious divorce;

- Women’s exclusion from Orthodox Jewish religious ritual and practice;

- Women’s exclusion from Orthodox Jewish communal leadership positions;

- Different or worse Jewish learning or teaching opportunities for women and girls, and/or dismissal of women’s intellectual capacities;

- Poor treatment of unmarried women and/or childless women within Orthodox communities.

In general, respondents did not identify other forms of oppression that might operate alongside sexism. Only in the case of the poor treatment of unmarried and childless women did respondents take an implicitly intersectional approach, noting how the disadvantages of being unmarried or childless are compounded for women. Only women mentioned this issue, describing it this way:

- “Without family, most observance is very isolated. There is virtually no inclusion of older, female singles, while single men get invited to meals and set up regularly.”

- “I am not married so I don’t feel the connection to the shul as much as if I were. Men attend minyan, get the most information and education so sometimes I feel estranged and it makes me a little sad.”

- “Women still have second-class status; single women, third-class status.”

What are the characteristics of Modern Orthodox Jews who are experiencing cognitive dissonance? Table 4 shows the results of a logistic regression model of experiencing cognitive dissonance on sociodemographic characteristics, including sex. Holding other factors constant, women were more likely than men to experience cognitive dissonance as a result of conflicting religious and feminist commitments. According to the model, the average probability of experiencing cognitive dissonance as a result of conflicting religious and feminist commitments was 22% for women and 7% for men.

Table 4.

Logistic regression of experiencing cognitive dissonance on sociodemographic characteristics (coef.).

Additionally, holding other factors constant, respondents with graduate degrees were more likely than those with lower levels of educational attainment to experience cognitive dissonance, and respondents ages 65 and older were less likely than younger respondents to experience cognitive dissonance. Marital status, geographic region, household income, labor force participation and whether the respondent belonged to the Orthodox community in childhood were not independently related to experiencing cognitive dissonance.

3.2. Orthodox Feminist Stance

What is the relationship between cognitive dissonance stemming from commitment to both Orthodoxy and feminism, and beliefs about the role of women within Orthodox Judaism? Using LCA, the analysis identified four distinct “classes” or stances toward Orthodox feminism. The results of the LCA are shown in Table 5: the class probability parameters specify the relative prevalence (size) of each class, and the item parameters indicate the probability of an individual in that class to endorse the item. The class names “strong feminist,” “cautious feminist,” “unbothered” and “oppositional” were chosen by the author. A narrative description of each class follows Table 5.

Table 5.

Latent class model parameters.

- The “strong feminist” class (41% of respondents) demonstrated near-universal support for expanded roles for women in Torah study and teaching, including co-ed religious classes and women teaching from the pulpit. The class also demonstrated near-universal support for expanded roles for women in organizational leadership, including as synagogue presidents and as titled clergy, and for women’s inclusion across several diverse areas of Jewish ritual life. Individuals in the strong feminist class had an 88% probability of saying that rabbis opposed to increased women’s roles pose problems for their Jewish community.

- The “cautious feminist” class (31% of respondents) also demonstrated near-universal support for expanded roles for women in Torah study and teaching, although individuals in this class had only a 68% probability of supporting women teaching from the pulpit. This class also demonstrated near-universal support for expanded roles for women in organizational leadership in general, although their views on women as clergy were mixed. In general, this class was likely to be favorable or neutral toward women’s inclusion in other areas of Jewish ritual life. These individuals had a 62% probability of saying that rabbis opposed to increased women’s roles pose problems for their Jewish community.

- The “unbothered” class (20% of respondents) demonstrated near-universal support for expanded roles for women in Torah study and teaching in general, but not necessarily for co-ed religious classes or for women teaching from the pulpit. The class also supported expanded roles for women in organizational leadership in general, but were unlikely to favor women as synagogue presidents or clergy. Individuals in this class were likely to be neutral or unsure about women’s inclusion in other areas of Jewish ritual life, and they were about equally likely to see rabbis opposed to and advocating for increased women’s roles as problems for their Jewish community.

- The “oppositional” class (8% of respondents) was more likely than not to support expanded roles for women in Torah study, teaching and organizational leadership in general, but this support was far from universal. In particular, individuals in this class were very likely to oppose women teaching from the pulpit or serving as clergy. They were generally neutral about or opposed to women’s inclusion in other areas of Jewish ritual life, and they had an 84% likelihood of thinking that rabbis opposed to increased women’s roles did not pose a problem to their Jewish communities.

After respondents were assigned to the latent class to which they had the greatest probability of belonging, a multinomial logistic regression model of Orthodox feminist stance on experiencing cognitive dissonance and sociodemographic characteristics was run. Results are shown in Table 6. Holding other factors constant, respondents who experienced cognitive dissonance were more likely to have a strong or cautious Orthodox feminist stance. Even holding the experience of cognitive dissonance constant, women were more likely than men to have a strong or cautious Orthodox feminist stance.

Table 6.

Multinomial logistic regression of Orthodox feminist stance on experiencing cognitive dissonance and sociodemographic characteristics (coef.).

Additionally, holding other factors constant, respondents from the West were more likely than those from the East to have a strong feminist stance, and those from the South were least likely; those with advanced degrees were more likely to have a strong or cautious feminist stance, while those without college degrees were more likely to have an oppositional stance; those with the lowest annual household incomes were more likely to have an oppositional stance; and those who were raised Orthodox were less likely to have a strong feminist stance. Age, marital status and labor force participation were not independently related to Orthodox feminist stance.

Recall that in this data set, 14% of respondents were coded as experiencing cognitive dissonance as a result of the conflict between their religious and feminist commitments, and 41% were in the “strong feminist” class. Using the model shown in Table 6, it is possible to predict changes in Orthodox feminist stance were the proportion of the population experiencing cognitive dissonance to increase. If all respondents were to experience cognitive dissonance, the proportion in the “strong feminist” class would increase to 71%. Thus, the experience of cognitive dissonance is associated with substantial commitment to Orthodox feminism, including support for women as titled clergy.

3.3. Orthodox Jewish Beliefs

What is the relationship between cognitive dissonance stemming from a commitment to both Orthodoxy and feminism, and Orthodox Jewish beliefs? The index of Orthodox Jewish beliefs was modelled as a function of the binary cognitive dissonance variable and the sociodemographic variables in Table 1. Results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Linear regression of Orthodox Jewish belief index on experiencing cognitive dissonance and sociodemographic characteristics (coef.).

Holding other factors constant, respondents who experienced cognitive dissonance had lower scores on the belief index. Other factors that were independently, negatively related to the belief index were: being younger than 35, living in the West as opposed to the East, having an advanced degree and being a student or retired. Factors that were independently, positively related to the belief index were: earning less than the typical household income and being raised Orthodox. Sex and marital status were not independently related to the belief index.

Again, recall that in this data set, 15% of respondents were coded as experiencing cognitive dissonance as a result of the conflict between their religious and feminist commitments, and the mean score on the belief index was 6.9. According to the model shown in Table 7, if all respondents experienced cognitive dissonance, the mean index score would be 4.7—a 32% decrease. Thus, the experience of cognitive dissonance is associated with substantial religious doubt.

4. Discussion

This study explores three critical questions related to how religious individuals confront the tension between feminist and religious commitments. First, how do religious individuals understand feminism as it relates to their religious lives? Second, how does feminist consciousness penetrate religious communities? Third, what is the impact of cognitive dissonance on individuals’ religious beliefs?

This study provides evidence of widespread cognitive dissonance among US Modern Orthodox Jews due to the tension between feminism and Orthodox Judaism. A non-trivial proportion of the population—14% of the study’s respondents—reported that issues relating to women or women’s roles in Orthodoxy cause them the most pain or unhappiness as Orthodox Jews. Most of the respondents’ concerns revolved around what they perceived as unjust sex-based discrimination, such as women’s disadvantageous position in Orthodox Jewish divorce. This focus on discrimination and unequal opportunity mirrors the concerns of classical liberal feminism in the 1960s and 1970s, at the beginning of the second-wave feminist movement.

How does feminist consciousness enter the Orthodox Jewish community? This study addressed this question by looking for independent relationships between sociodemographic characteristics and experiencing cognitive dissonance related to the conflict between feminism and Orthodoxy. First, although women were more likely than men to experience cognitive dissonance, men also experienced it: holding other factors constant, the average probability of experiencing cognitive dissonance was 22% for women and 7% for men. Second, in line with Manning (1999) and Fishman (2000), this study showed a strong, independent correlation between having a graduate degree and experiencing cognitive dissonance, whereas labor force participation was not independently related to experiencing cognitive dissonance. It is possible that university study, rather than labor force participation, exposes individuals to egalitarian ideas that challenge traditional religious beliefs. It is also possible that only certain segments of the labor force—those that require advanced degrees—expose individuals to such ideas. Either way, the high prevalence of advanced degrees among Modern Orthodox Jews suggests that issues relating to women or women’s roles may also be a source of pain for a sizeable number of others, albeit not the most acute source of pain.

Finally, contrary to prior research (Davidman 1991; D. R. Kaufman 1991), this analysis found that Modern Orthodox Jews who became Orthodox after childhood were no less likely to experience cognitive dissonance vis-à-vis Orthodoxy and feminism than those who grew up Orthodox. In other words, not all newly Orthodox women have adopted traditional Orthodox beliefs about gender.

The classic responses to cognitive dissonance would be (1) trying reduce dissonance by changing beliefs, actions or environments and (2) avoiding situations and information that accentuate or increase the dissonance (Festinger 1965). Because the data set included only Jews whose current identification was Modern Orthodox, this study could not assess the impact of cognitive dissonance on leaving Orthodoxy altogether. However, it did examine the relationship between cognitive dissonance and deviations from traditional Orthodox beliefs.

Experiencing cognitive dissonance was strongly correlated with the “strong feminist” stance, which included near-universal support for expanding roles for women in learning, teaching, organizational leadership and ritual. Experiencing cognitive dissonance also had a strong, negative correlation with Orthodox Jewish beliefs in general. Individuals who experienced women’s roles in Orthodox Judaism as a primary source of pain were less likely to believe in fundamental tenants of Orthodoxy, including that God gave both the written and oral Torah to Moses on Mt. Sinai. Taken together, these findings suggest that not only do Modern Orthodox Jews experience cognitive dissonance related to the conflict between feminism and Orthodoxy, but this dissonance actually propels change in religious beliefs.

Secular education was also independently associated with both Orthodox feminist beliefs and Orthodox Jewish beliefs in general, over and above its association with experiencing cognitive dissonance. Those with advanced degrees were more likely to have a “strong feminist” stance and a lower score on the Orthodox Jewish belief index. Those without college degrees were more likely to have an “oppositional” stance, with a 72% likelihood of opposing women teaching from the pulpit and a 98% likelihood of opposing women serving as clergy, and a higher score on the Orthodox Jewish belief index.

The strong correlations between higher education, cognitive dissonance, Orthodox feminist beliefs and Orthodox Jewish beliefs in general point to a key area for future research. What specific beliefs about feminism do Orthodox Jews encounter during higher education, and how do they both adopt and criticize these beliefs? The data set used in this study did not include information about how Modern Orthodox Jews think about feminism in general, outside of a religious context. Such information would be valuable in understanding the nature of the cognitive dissonance that is driving change in Orthodox Judaism, as well as to understand what is unique in how Orthodox Jews understand feminism, specific to their positions in the world.

This study does delve deeply into how Modern Orthodox Jews think about the role of women within Orthodoxy. The findings suggest the dual potential of cognitive dissonance related to feminism and religion. On the one hand, cognitive dissonance may inspire individuals change their religious beliefs and practices in a way that redresses sexism within religious traditions. On the other hand, cognitive dissonance may also threaten the demographic vitality of religious communities insofar as they fail to provide individuals with a mechanism to relieve their psychic discomfort.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Mark Baker at Nishma Research provided access to the 2017 Nishma Research Survey of American Modern Orthodox Jews. A public use data set is available from the Berman Jewish Databank.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Adler, Rachel. 1998. Engendering Judaism: An Inclusive Theology and Ethics. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Pamela Sue, and Beverley Clack, eds. 2003. Feminist Philosophy of Religion: Critical Readings. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Pamela Sue. 1998. A Feminist Philosophy of Religion: The Rationality and Myths of Religious Belief. Oxford and Malden: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Batson, C. Daniel. 1975. Rational Processing or Rationalization?: The Effect of Discontinuing Information on a Stated Religious Belief. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 32: 176–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaman, Lori G. 2001. Molly Mormons, Mormon Feminists and Moderates: Religious Diversity and the Latter Day Saints Church. Sociology of Religion 62: 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasher, Brenda E. 1998. Godly Women: Fundamentalism and Female Power. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braude, Ann. 2004. Transforming the Faiths of our Fathers: Women Who Changed American Religion. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Burris, Christopher T., Eddie Harmon-Jones, and W. Ryan Tarpley. 1997. “By Faith Alone”: Religious Agitation and Cognitive Dissonance. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 19: 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 1990. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1989. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 14: 538–54. [Google Scholar]

- Davidman, Lynn. 1991. Tradition in a Rootless World: Women Turn to Orthodox Judaism. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davidman, Lynn. 2000. Review of the book God Gave Us the Right, by C. Manning. Contemporary Sociology 29: 523–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Kathy. 2008. Intersectionality as Buzzword: A Sociology of Science Perspective on What Makes a Feminist Theory Successful. Feminist Theory 9: 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecklund, Elaine Howard. 2003. Catholic Women Negotiate Feminism: A Research Note. Sociology of Religion 64: 515–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, Leon. 1956. When Prophecy Fails. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, Leon. 1965. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, Sylvia Barack. 1993. A Breath of Life: Feminism in the American Jewish Community. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, Sylvia Barack. 2000. Changing Minds: Feminism in Contemporary Orthodox Jewish Life. New York: American Jewish Committee. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, Sylvia Barack. 2007. The Way into the Varieties of Jewishness. Woodstock: Jewish Lights Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Blu. 1981. On Women and Judaism: A View from Tradition. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, R. Marie. 1997. God’s Daughters: Evangelical Women and the Power of Submission. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, Rita M. 1996. Feminism and Religion: An Introduction. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hacohen, Aviad. 2004. Tears of the Oppressed: An Examination of the Agunah Problem: Background and Halakhic Sources. Edited by Blu Greenberg, Menachem Elon and Emanuel Rackman. Jersey City: Ktav Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman Halbertal, Tova. 2002. Appropriately Subversive: Modern Mothers in Traditional Religions. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, Tova. 2007. Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation. Hanover: Brandeis University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, E. Tory, Ruth Klein, and Timothy Strauman. 1985. Self-Concept Discrepancy Theory: A Psychological Model for Distinguishing among Different Aspects of Depression and Anxiety. Social Cognition 3: 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooks, Bell. 1981. Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism. Boston: South End Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, Julie. 2003. Evangelical Christian Women War Stories in the Gender Battles. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jantzen, Grace. 1999. Becoming Divine: Towards a Feminist Philosophy of Religion. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, Debra R. 1991. Rachel’s Daughters: Newly Orthodox Jewish Women. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, Michael. 1993. The Woman in Jewish Law and Tradition. Northvale: J. Aronson. [Google Scholar]

- Kinahan, Anne-Marie. 2004. Women Who Run from the Wolves: Feminist Critique as Post-Feminism. In Feminisms and Womanisms: A Women’s Studies Reader. Edited by Althea Prince, Susan Silva-Wayne and Christian Vernon. Toronto: Women’s Press, pp. 119–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza, Stephanie T., John J. Dziak, Liying Huang, Aaron T. Wagner, and Linda M. Collins. 2015. LCA Stata Plugin Users’ Guide (Version 1.2). University Park: The Methodology Center, Penn State. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld, Paul F., and Neil W. Henry. 1968. Latent Structure Analysis. New York: Houghton-Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Mahaffy, Kimberly A. 1996. Cognitive Dissonance and Its Resolution: A Study of Lesbian Christians. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 35: 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, Christel. 1999. God Gave Us the Right: Conservative Catholic, Evangelical Protestant, and Orthodox Jewish Women Grapple with Feminism. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nishma Research. 2017. The Nishma Research Profile of American Modern Orthodox Jews. Available online: http://nishmaresearch.com/ (accessed on 26 October 2018).

- Nylund, Karen L., Tihomir Asparouhov, and Bengt O. Muthén. 2007. Deciding on the Number of Classes in Latent Class Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling: A Monte Carlo Simulation Study. Structural Equation Modeling 14: 535–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozorak, Elizabeth Weiss. 1996. The Power, but not the Glory: How Women Empower Themselves through Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 35: 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paludi, Michele Antoinette. 2016. Feminism and Religion: How Faiths View Women and Their Rights. Santa Barbara: Praeger. An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Susan Frank. 2002. The Cambridge Companion to Feminist Theology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2013. A Portrait of Jewish Americans: Findings from a Pew Research Center Survey of U.S. Jews. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2016. The Gender Gap in Religion around the World. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Plaskow, Judith. 1991. Standing again at Sinai: Judaism from a Feminist Perspective. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco. [Google Scholar]

- Roness, Michal. 2013. The Yoetzet Halakhah: Avoiding Conflict While Instituting Change. In Gender, Religion, & Family law: Theorizing Conflicts between Women’s Rights and Cultural Tradition. Edited by Lisa Fishbayn Joffe and Sylvia Neil. Hanover: Brandeis University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Susan D. 1987. Women Warriors: The Negotiation of Gender in a Charismatic Community. Sociological Analysis 48: 245–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, Tamar. 2000. Modern Orthodoxy and the challenge of feminism. Studies in Contemporary Jewry 16: 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Tamar. 2004. Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism. Hanover: Brandeis University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saxe, Leonard, Theodore Sasson, and Janet Krasner Aronson. 2014. Pew’s portrait of American Jewry: A reassessment of the assimilation narrative. In American Jewish Year Book 2014. Edited by Arnold Dashefsky and Ira Sheskin. New York: Springer International Publishing, pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel, Landon. 2016. The Gender Pray Gap: Wage Labor and the Religiosity of High-Earning Women and Men. Gender & Society 30: 643–69. [Google Scholar]

- Shamir, Ronen, Michal Shitrai, and Nelly Elias. 1997. Religion, feminism, and professionalism: The case and cause of women Rabbinical Advocates. Megamot 38: 313–48. [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, Judith, and Susan Elizabeth Gerard. 1990. ‘We Are Not Doormats’: The Influence of Feminism on Contemporary Evangelicals in the United States. In Uncertain Terms: Negotiating Gender in American Culture. Edited by Faye Ginsburg and Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing. Boston: Beacon Press, pp. 98–117. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner-Aeschliman, Sherrie, and Armand L. Mauss. 1996. The Impact of Feminism and Religious Involvement on Sentiment toward God. Review of Religious Research 37: 248–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocks, Janet. 1998. To Stay or Leave? Organizational Legitimacy in the Struggle for Change among Evangelical Feminists. In Contemporary American Religion: An Ethnographic Reader. Edited by Penny Edgell Becker and Nancy L. Eiesland. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, pp. 99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Sztokman, Elana Maryles. 2011. The Men’s Section Orthodox Jewish Men in an Egalitarian World. Hanover: Brandeis University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thumma, Scott. 1991. Negotiating a religious identity: the case of the gay Evangelical. Sociological Analysis 52: 333–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Rosemarie, and Tina Fernandes Botts. 2017. Feminist Thought: A More Comprehensive Introduction. London: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Uzan, Elad. 2016. From Social Norm to Legal Claim: How American Orthodox Feminism Changed Orthodoxy in Israel. Modern Judaism 36: 144–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, Mary Jo. 1995. New Catholic Women: A Contemporary Challenge to Traditional Religious Authority. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woodhead, Linda. 2008. Gendering Secularization Theory. Social Compass 55: 187–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, Danielle Dunand. 2015. Young Arab Muslim Women’s Agency Challenging Western Feminism. Affilia 30: 145–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. | Griffith (1997) discusses intersectionality briefly, only to note that mainstream feminists have not responded to the substantive critiques of religious women in the way they have responded to the substantive critiques of women of color. |

| 2. | There is also significant Jewish feminist scholarship outside of Orthodoxy (e.g., Adler 1998; Plaskow 1991), which rests on different theological assumptions about the nature of revelation and covenant. |

| 3. | Only 2% of US Jews are converts to Judaism (Pew Research Center 2013). The Nishma survey did not ask about conversion, but the vast majority of respondents who began to identify as Orthodox at age 11 or older were likely raised as non-Orthodox Jews. |

| 4. | A small number of individuals wrote that that an issue relating to women or women’s roles in Orthodoxy was a source of satisfaction, joy or meaning (N = 17), or that Orthodox feminism itself caused them pain, e.g., “I am so frustrated with women on the left speaking for all women” (N = 12). These individuals were not coded as experiencing cognitive dissonance. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).