1. The Notion of the Global East

The Inaugural Conference of the East Asian Society for the Scientific Study of Religion set the theme as “Religiosity, Secularity, and Pluralism in the Global East”. The terms “religion”, “religiosity”, “secularity”, and “pluralism” all need careful examination and reexamination in the context of the Global East. But first of all, what is the Global East?

The Global East is a cultural and social concept that includes East Asian societies and ethnic communities of East Asians around the world that maintain East Asian cultural traditions, are closely connected with East Asia, and play important roles in East Asian developments. These societies, communities, and individuals share distinct social and cultural characteristics. The Global East, as a new concept, is necessary primarily because the existing groupings of countries in the world are either Euro-centric or North-Atlantic-centric and may lead to improper understanding or misunderstanding of East Asian societies, communities, and individuals. Moreover, this concept may help in the effort to reconceptualize and improve measurements of “religion”, “religiosity”, “secularity”, and other key terms in the social scientific study of religion in general.

When we take a broad view of the contemporary world, there have been two widely-used ways of grouping countries in some sort of geographical sense: East versus West, which was commonly used during the Cold War, and North versus South, which has become popular since the 1970s. While the East-West dichotomy was based on the ideological conflict between the Communist-ruled countries and the so-called “free world” (

Buchholz 1961;

Loth 1994),

1 the North-South division is primarily about the economic divide between developed countries and underdeveloped or developing countries (

Horowitz 1966;

Erb 1977;

Eckl and Weber 2007;

Reuveny and Thompson 2007). However, it is difficult to fit East Asia into either of these constructs.

Ideologically, some of the major East Asian countries, such as Japan, South Korea, or the Republic of China on Taiwan, belonged to the so-called West during the Cold War. Although ideological conflicts have waned in the contemporary world, Communist ideology has notably persisted in three major Asian countries: China, North Korea, and Vietnam (with the only other Communist nation being Cuba in Central America). The ideological persistence in these Asian countries cannot be brushed off because it has significant social, political, and cultural consequences for the residents of those societies and beyond.

2Economically, some East Asian countries are said to belong to the so-called South, even though they all lie in the northern hemisphere. More importantly, in terms of the economy, things have been changing dramatically in the last few decades. Japan was the first developed country in the Far East. Since the 1960s, we have witnessed the rapid rise of the four little tigers or dragons: South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore (

Midgley 1986;

Vogel 1992;

Morris 1996;

Hamilton 2007). This was followed by the so-called tiger cubs of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand (

Heng and Niblock 2014), and the big dragon of China (

Burstein and Keijzer 1999). In recent years, Vietnam has also experienced an economic upsurge (

Hayton 2010). In contrast, some of the Eastern European countries in the so-called global North have struggled economically in recent decades (

Tlostanova 2011).

It was Max Weber who first brought scholarly attention to the relationship between religion and the economy. He tried to explain why modern rational capitalism first emerged in the Protestant West, but not elsewhere, and he made careful examination of the religions of China (i.e., Confucianism and Daoism) and India (i.e., Hinduism and Buddhism) in addition to Christianity, Judaism, and Islam (

Weber [1904] 1930,

[1920] 1951,

[1917] 1952 and

[1916] 1958). I would acknowledge that these books by Weber are full of insights and should be read by all students and scholars who study religion in East Asia, but I must also say that many parts of these writings, even some of Weber’s main conceptualizations, are off the mark. One of the most obvious problems is that Weber grouped Buddhism into the religion of India. In fact, by the time that Weber was writing on these in the 1910s and 1920s, Buddhism had been a major religion in East Asia for nearly two thousand years, but was negligible in India proper. More importantly, throughout East Asia, shamanism and folk religions were much more prevalent in society than institutionalized religions (see, e.g.,

Yang 1961). Furthermore, for much of the last two millennia, several institutionalized religions have coexisted without a religious monopoly in most parts of East Asia, a situation radically different from the West where one of the multiple forms of Christianity dominated for centuries.

In short, both of these commonly used groupings are Euro-centric or North-Atlantic-centric notions. That is, both of these groupings are from the vantage point of Western Europe and North America. Additionally, that presents a problem for properly understanding a large segment of the world population. The North-Atlantic world has a combined population of about 1.1 billion, whereas East and Southeast Asia have a combined population of 2.3 billion people, or 30 percent of the world population. When 30 percent of the world population cannot easily be fitted into the conceptual constructs, we must find an alternative way to work. This is especially true when we study culture, religion, and society. Culturally, East Asian societies are distinct from the rest of the world; in East Asia, the predominant religious traditions have been a mixture of Confucianism, Buddhism, some indigenous traditions, such as Daoism or Shintoism, and local folk religions. Moreover, post-Weberian phenomena, especially the economic rise of East Asia and the spread of Christianity in East Asia, are very important for scholars who want to understand religion and the changing dynamics in East Asia today.

2. Christianity, Confucianism, Atheism, and Folk Religion in the Global East

Contemporary Western scholars have paid great attention to the phenomenon of Christianity moving to the “Global South”. For example, the historian, Philip Jenkins, published a book in 2002 with the title,

The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (

Jenkins 2002), which highlights the rapid growth of Christianity in the Global South, especially in Africa. By 2011, it had been updated and expanded into a third edition and translated into multiple languages (

Jenkins 2011). In 2006, he published a further book,

The New Faces of Christianity: Believing the Bible in the Global South, that highlighted even more prominently the imagery of the Global South. Continuing this popular trend, an

Encyclopedia of Christianity in the Global South (

Lamport 2018) was published just a few months ago. The editor, Mark A. Lamport, invited me to participate in the project. I told him that I did not like the notion of the Global South because Christians in East Asia would be obscured in this kind of generalization. Conceptualizing the project as describing Christians in the Global South makes it difficult to understand Christians in East Asia in their own place. As the Pew Research Center’s reports suggest (

Pew Research Center 2011,

2012), Christians in East Asia and among diasporic communities of ethnic East Asians comprise a significant segment of the Christian population in the world today. Geographically speaking, how can it be appropriate to group South Korea and China into the Global South? Both are obviously in the northern hemisphere. Culturally, their religious traditions are radically different from Africa and Latin America. It is against these cultural backgrounds that Christianity has swelled in a post-World War II context. Socially and economically, these countries are developed or are fast-developing. Despite my misgivings about the notion of the Global South, Mark Lamport encouraged me to write down my thoughts about Christianity in the Global South vs. the Global East, and eventually included my observations as an “afterword” in the Encyclopedia (

Yang 2018). I was pleased by his inclusiveness and openness toward critical reflections, but we need to do much more to change the narrative that renders East Asia both invisible and incomprehensible. We know that about 90 percent of Filipinos are Christian. Some surveys show that about 30 percent of South Koreans are Christian (

Pew Research Center 2011). The Singapore Census reports 18 percent Christian in 2010 (

SDS 2011). Christianity has been growing rapidly in China in the last few decades (

Yang 2016a). The growth of Christianity in East Asian societies is having a profound impact on the religious landscape of the world.

Another issue needing to be addressed is the supposed prevalence of Confucianism. Max Weber said that Confucianism was the major religion of China and, by expanding this line of thought, we could say that Confucianism was a major religion of East Asia, as many scholars do (e.g.,

Tu 1996). However, in social surveys, very few Chinese, Koreans, or Japanese self-identify as followers of Confucianism (

Yang and Tamney 2011). The Pew Research Center conducted a survey of Asian Americans in 2012. It reports that Christianity is a major religion among several Asian ethnic groups: Chinese Americans, Filipino Americans, Korean Americans, Japanese Americans, and Vietnamese Americans. The only exception is Indian Americans, of whom a majority are Hindus. Buddhism is a major religion among the Vietnamese, Japanese, Chinese, and Koreans, but not Indians. Again, where are the adherents of Confucianism? Extremely few Asians or Asian Americans self-identify with Confucianism.

These problems in surveys raise questions about the measurement of religiosity, but also the conceptualization of religion itself. In East Asia, people may admit to being Buddhist, Confucian, or Daoist, but would not admit to being religious, or belong to any religion, as they honestly do not regard Buddhism, Confucianism, Daoism, or Shintoism as religions. As one may infer, there is a language problem. In Chinese,

zongjiao 宗教 is a modern term, borrowed from Japanese, which was a

kanji translation from European languages (

Beyer 2013). During this translation and importation, the exact meaning was altered and it takes time for the populace to accept the translated concept. For many Asians today, religion is still not a concept in their everyday language, even though the political and cultural elites have adopted it into public institutions. For those who have received a secularist education that is heavily influenced by the French Enlightenment, religion is often a sabotaged concept in their normative, progressive thinking. Therefore, scholars in the social scientific study of religion have to find ways to learn and use the spiritual language of ordinary people.

In fact, even the cultural and political elites in Asia are confused and confusing. In China, Confucianism is not classified as a religion, but Daoism is. However, not many people self-identify with Daoism as a religion either. In real life, Daoism and the so-called folk religions share many of the same beliefs and practices. Some scholars want to include all folk religions in greater Daoism 大道教 or the religion of China (

Freedman 1974;

Lagerwey 2010). Others have argued to make Confucianism a religion, even the national religion of China (see

Billioud and Thoraval 2008;

Ownby 2009;

Sun 2013). These advocates often refer to the model of Hinduism as the religion of Indians or Shintoism as the state religion of Japan prior to 1945. They posit that if Indians and Japanese have their own named religions, why should the Chinese be treated differently? Indeed, Confucianism has been classified as one of the major religions in Indonesia. However, a scholarly question must be posed: Under what social and political conditions can you construct a religion (

Sun 2013)? In thinking about this question, we must also examine how successful the elite campaigns are in constructing the religions of Hinduism, Shintoism, Daoism, and Confucianism. What are their relationships with folk religions and other world religions? Additionally, how are things changing in the contemporary globalization era? These difficult questions lead to further questions worth pondering: Can non-Japanese convert to Shintoism, non-Indians convert to Hinduism, and non-Chinese convert to Daoism or Confucianism? In fact, Confucianism and Daoism have transcended Chinese boundaries and are shared by the Japanese, Koreans, and Vietnamese (see

Ivanhoe and Kim 2017), but we must ask a further question: Is this in a religious sense, in a philosophical sense, or in some other sense? These questions all need to be answered with care and nuance, and more importantly, with systematically collected data, objective analysis, and appropriate theoretical concepts in the social scientific study of religion.

A further problem is atheism. Religion is a universal phenomenon of human society. According to

Bellah (

2011), religion emerged along with the human race in the process of evolution. Of course, in any given society, be it a primitive society or modernized society, there are always some individuals who do not believe in any supernatural being or supernatural force. In other words, atheists are not a modern phenomenon; they have existed in all societies (

Stark and Finke 2000). However, atheism as a secularist ideology is a modern phenomenon, and it has a twisted understanding in an Asia that has been striving to modernize. By some measures, East Asian societies have the highest proportions of people claiming to be atheists. For example, according to the World Values Surveys (WVS), about five percent of Europeans (N = 62,545) and Americans (N = 2232) are “convinced atheists”, but there are nearly 30 percent of “convinced atheists” among South Koreans (N = 1200), 27 percent among the Chinese (N = 2300), 17 percent among the Taiwanese (N = 1238), and 11 percent among the Japanese (N = 2443). Hong Kong was first included in the WVS in 2005, which revealed five percent of atheists in the city. In the 2013 sample of 1000 Hong Kongers, however, 55 percent reported to be atheists. Obviously, something must be wrong with these surveys, even though the World Values Surveys are considered one of the best cross-national surveys.

Returning to Robert Bellah, in 1985, he and his colleagues (

Bellah et al. 1985) coined a new term, Sheilaism, for a new phenomenon in American religion: Individualized eclecticism—taking some elements from various religious or spiritual traditions to form one’s own religion. Sheila is a good hearted and spiritually conscious person, but very individualized in terms of religion. Can we find Sheila in East Asia? Probably, the majority of people in these societies can be called “Asian Sheilas”. It is common for East Asians to take something from Confucianism, Daoism, Buddhism, and other sources to form their own individualized spirituality. Instead of converting to one particular religion, they move around different religions without dedication to or even identification with any one in particular. For example, many Japanese may be said to be “Asian Sheilas”, in that they use the birth rites of Shinto, the marriage rites of Christianity, and the funeral rites of Buddhism, yet they may also say that they are atheist.

In the same train of thought, scholars of religion in the United States have noticed several new phenomena: The rise of Sheilaism and New Age spiritualties in the 1980s, the rise of people who claim to be “spiritual but not religious” since the 1990s (

Tong and Yang 2018), and the rapid rise of religious “nones”, or those who claim no religion at all even though most hold some religious beliefs and engage in selected religious practices. These may be new phenomena in the new world, but I would say, “Hello, America! Welcome to East Asia”. In East Asia, these are traditional patterns of being religious or spiritual. In modern scholarship of Chinese studies, we often refer to these phenomena as folk religious expressions. Can we refer to these new phenomena in the United States as new folk religion in America? I think so, but the writers of the Pew Research Center’s report,

The Future of World Religions (

Pew Research Center 2015), did not. This report includes folk religion among Asians, Africans, Native Americans, and aboriginal Australians, but not among Europeans or European Americans. This is another sign of Euro-centrism in the conceptualization of religion and religiosity, even though it probably happened unconsciously. Regardless, we need to study these widespread or universal phenomena as part of the postmodern or late modern world, both in East Asia and North America (

Yang 2016b).

3. Secularization in the Global East?

Secularization theories have dominated the world, especially the intelligentsia, for a long time. For several decades following the 1960s, Peter Berger was one of the most important theorists who argued that modernization will necessarily lead to religious decline (

Berger 1967,

1969). Both of the keynote speakers at the inaugural EASSSR conference,

Casanova (

1994) and

Davie (

1994,

2000), have played important roles in questioning these assumptions. Facing a myriad of empirical evidence as well as theoretical development, Peter Berger himself rescinded his secularization theory in the 1990s (

Berger 1999;

Berger et al. 2008).

Warner (

1993,

1997),

Stark and Finke (

2000),

Yang (

2006,

2011), and many others have argued that there has been a paradigm shift: The social scientific study of religion has shifted focus from explaining religious decline to explaining religious vitality in modern societies. Recently, however,

Voas and Chaves (

2016) have revived the debate again, arguing that secularization is finally taking effect in the United States as well as Europe.

What about East Asia? In China, secularization was a state-engineered program, but since the 1970s, religions have been reviving and becoming increasingly important in society (

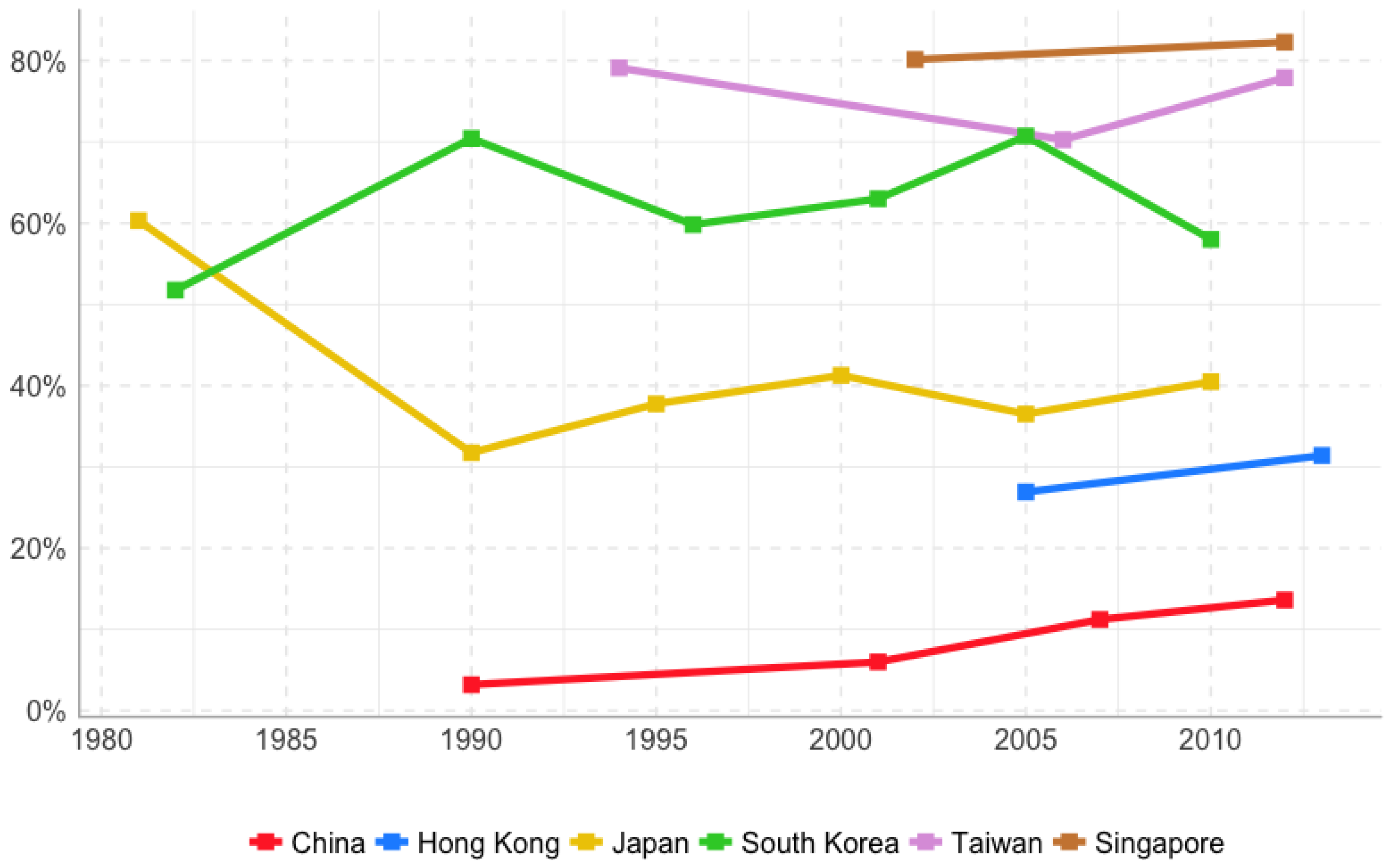

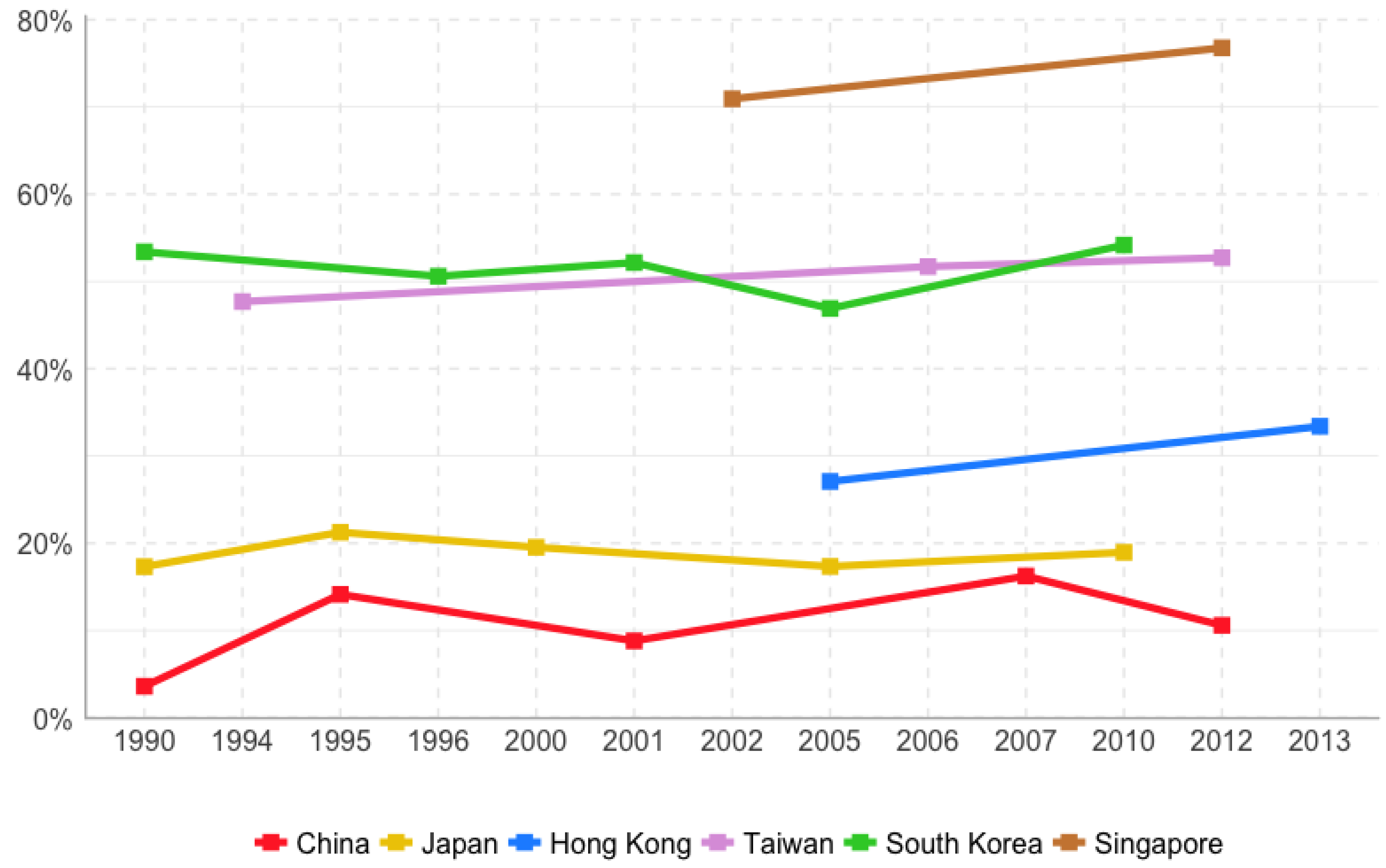

Yang 2014a). How about other East Asian societies? Recently, my students and I began to explore some survey data. Unfortunately, survey data are very limited and less reliable for this part of the world. The best available cross-national survey data is probably the World Values Surveys, which began in 1990 and included some Asian societies in various years. Based on these limited surveys and our preliminary analysis, we do not see a pattern of religious decline. Take the question of religious affiliation as an example (see

Figure 1), we see certain fluctuations in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, but no clear indication of decline. In other societies, there is even an increase. Take another question as an example, the importance of religion in their lives (see

Figure 2). Again, there is no decline and perhaps some slight increase in all of these Asian societies.

We have also explored other datasets. In the Japan General Social Survey, the proportion of people who claim to have a religion or a family religion has remained about the same since the year, 2000. The proportion of people who claim to be Buddhists fluctuated a lot, but there is no clear pattern of decline. In the Korea General Social Survey, there are noticeable fluctuations of the self-identified Protestant Christians and Buddhists, but no clear decline of religion in general. The same is true of religious attendance. Similarly, the Taiwan Social Change Surveys, which began in the 1980s, show no clear signs of religious decline, although there have been changes. Of course, all of these surveys were done within a relatively short period of time and may not fully capture the historical trajectories. We need more and better surveys as well as other types of empirical data.

In the social scientific study of religion and spirituality in the Global East, a key problem is how to measure religion and religiosity. The existing measures commonly used in the West and around the world are primarily based on Judeo-Christian understandings of identity, membership, and attendance. To be more precise, in the Judeo-Christian context, it is assumed that religious identity is exclusive, that every religious person is a member of a local congregation that is part of a denomination or a distinct religion, and that regular activities include weekly attendance at a corporate worship service. However, East Asian religions have distinct characteristics: Religious identity is not necessarily exclusive, religious practice is not based on a weekly rhythm, individual devotion or practice is at least as important as corporate rituals, and the boundaries of religiosity and secularity are ambiguous or blurred. Moreover, these societies are characterized by a lack of religious monopolies. Instead, the situation is more akin to a religious oligopoly, where several religions are considered acceptable while many others are suppressed by the state and the public (see

Yang 2014b).

4. Conclusions

In sum, the cultural and social differences of East Asian societies from the rest of the world make it necessary to adopt a new concept—the Global East. Global East societies, communities, and individuals share some common cultural and religious traditions, including Confucianism, Buddhism, Daoism/Shintoism/Shamanism, and other local or folk religions. Christianity has grown rapidly in some of these societies and communities, but not others. This is not to gloss over internal differences of East Asian societies. Good scholarship should examine both particularities and commonalities, but the commonalities in East Asia deserve to be examined carefully. The Global East is a cultural and social concept enabling such studies together with cross-national comparisons in that part of the world.

It is important to point out that, given their distinct cultural and community characteristics in the globalizing world, the Global East not only includes East Asian societies, but also includes diasporic communities of ethnic East Asians in other countries around the world, as they tend to share more similarities with East Asian societies than with others. Furthermore, in this era of globalization, selected westerners have adopted traditional religions or spiritualties of the Global East. Recently, I reviewed

Dream Trippers: Global Daoism and the Predicament of Modern Spirituality (

Palmer and Siegler 2017), which describes Americans and other Westerners who have become Daoists and have taken trips to sacred mountains in China to meditate in caves (

Yang forthcoming). These are all part of the Global East.

Religion in the Global East presents theoretical and methodological challenges for the social scientific study of religion. First, there are language problems, as discussed above. Second, religion-state relations in the Global East have been very different from Europe and America. Religious monopolies have been rare throughout the history of societies in the Global East, as multiple religions have coexisted for long periods of time. Third, at the micro level, religious identity may not be exclusive or salient. A majority of people are open to beliefs and practices of multiple religions, yet may or may not self-identify with any particular religion, or when they do, may identify with multiple religions. Simply identifying these characteristics should be sufficient to emphasize not only the distinctiveness, but the importance of the concept of the Global East.

Religion in the Global East presents great opportunities for the social scientific study of religion in the globalizing world as well. First, if we can develop good measures of religiosity in the Global East, it should substantially improve the measurement of religiosity around the globe (

Chao and Yang 2018). Second, cross-referencing and comparative studies of religions in the Global East are likely to shed new light on many theoretical issues in the general social science of religion, including the debate on secularization. Third, a better, scholarly understanding of the religion-state relations in the Global East may help to present meaningful alternatives to the existing models of modern religion-state relations.

There are numerous scholarly associations for the study of religion based in North America and Europe. Religions in East Asia are quite distinct from other parts of the world, and religious change in this part of the world has been rapid and dramatic. I very much hope that the East Asian Society for the Scientific Study of Religion will become an important platform for scholars of religions in East Asia and elsewhere to regularly engage with each other. Together, we can make a significant contribution to better understandings of religion in the modern world, and to the methodology and theory necessary for the social scientific study of religion both in East Asia and in general.