2.1. Data on Religiosity in the Observed Region

First, we will present the religious panorama of the observed societies (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, Kosovo, Albania, Montenegro). In these countries, members of Orthodox Christianity and Islam are the dominant ones, with only 5% of Catholics.

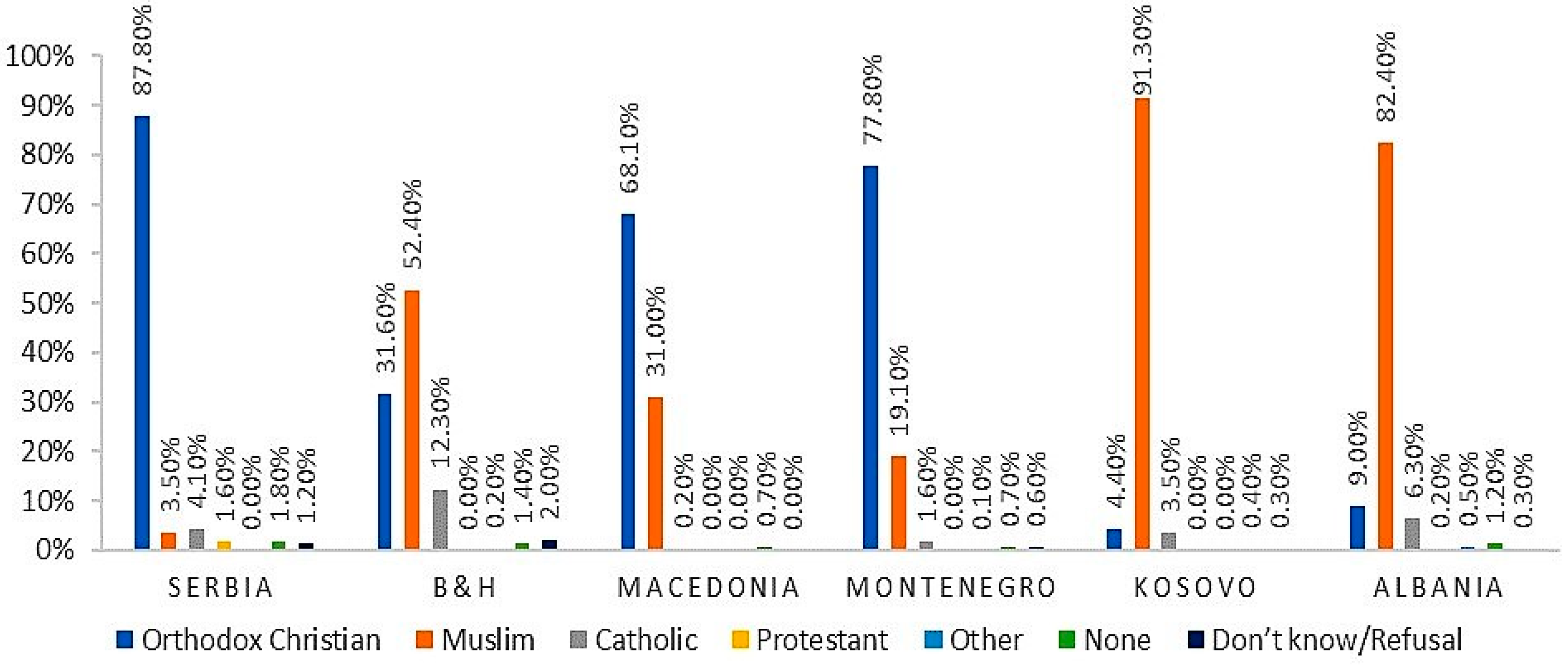

Figure 1 shows the distribution of confessions in the observed countries.

In Serbia, Macedonia, and Montenegro, Orthodox Christians are the most dominantly present, while in Bosna and Herzegovina, Albania and Kosovo, the majority of believers are Muslims. Taking into account the number and distribution of confessionality in the observed countries presented in the below graph, only the three most populous confessions—Orthodox, Muslim, and Catholic, will be included in the analyses below.

A specific phenomenon found in this region is the difference between confessionality and religiosity. Namely, due to the merging of ethnic and religious identities (

Gavrilović et al. 2016), as well as the ethnic conflicts that took place in this region, respondents claim that they belong to a religious community (Orthodox, Muslim, or Catholic) but in some cases, they are not necessarily religious. This phenomenon of belonging without believing (

Davie 2005) is not exclusively characteristic of the territory of Southeastern Europe, yet the causes here are specific because of identity struggles, as mentioned above (

Gavrilović and Đorđević 2018).

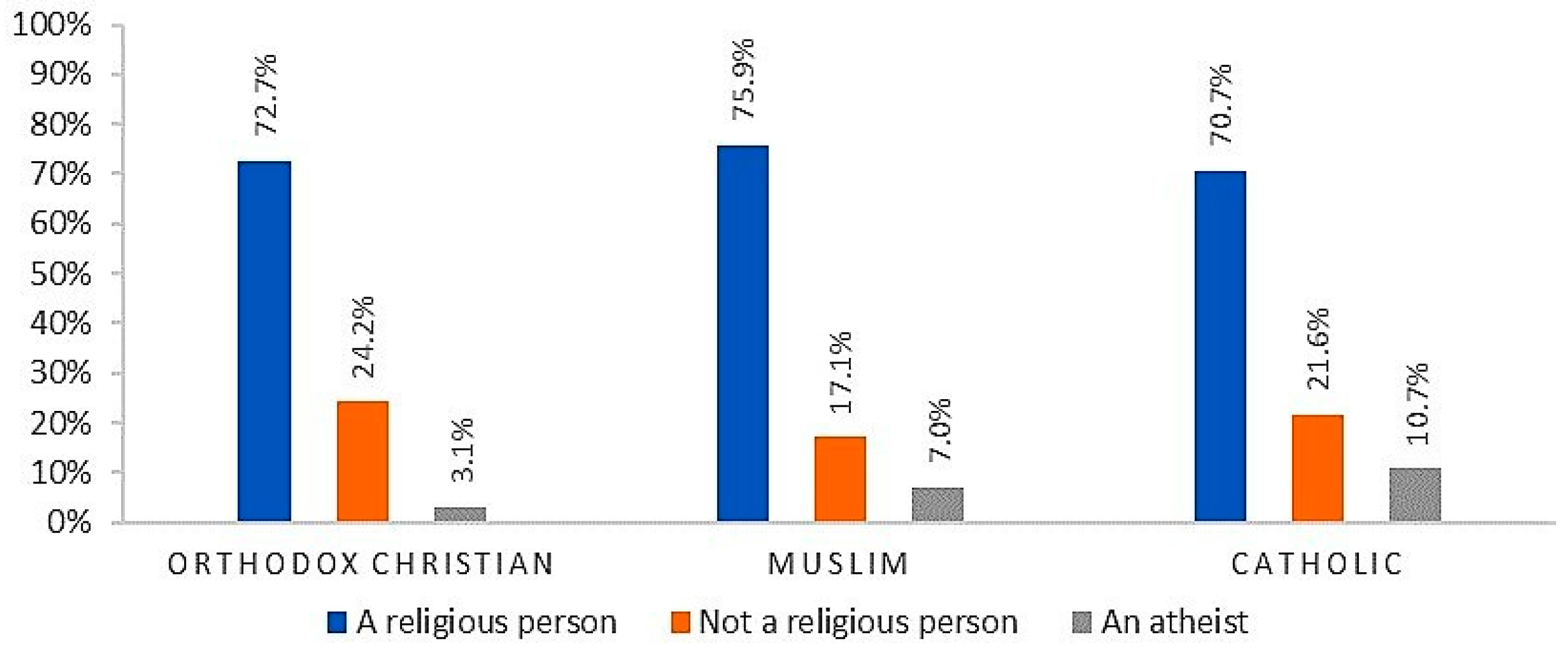

Figure 2 shows religious self-declaration in these countries.

Among those declared confessional members, there were some who claim not to be religious or even to be atheists. The number of those claiming to be atheists was the highest in Albania (and can be seen in

Figure 1, over 80% of the Albanian population declared themselves Muslim). This percentage is significantly higher in comparison to all of the other observed countries since atheisation in Albania during the socialist period was the most extensive of all, and its consequences are still evident today. On the other hand, in Albania as a relatively ethnically homogenous country, there have been no open ethnic conflicts, unlike the case in the other countries, to initiate the renewal of religiosity as an indicator of ethnic differences. Albania also possesses the highest number of those who refuse to answer the question on religiosity—no less than 21.7%.

9Therefore, we used confession as a factor of religious self-declaration for further analyses (

Figure 3). The lowest proportion of religious people can be found among the Orthodox population (around 25% of them consider themselves non-religious) but the fewest atheists as well (3%). Muslims are the most religious of all (76%), while the highest percentage of atheists can be found among Catholics (over 10%). The observed differences between confessions were also statistically significant at the level of χ

2 (5427,6) = 77.369,

p < 0.001.

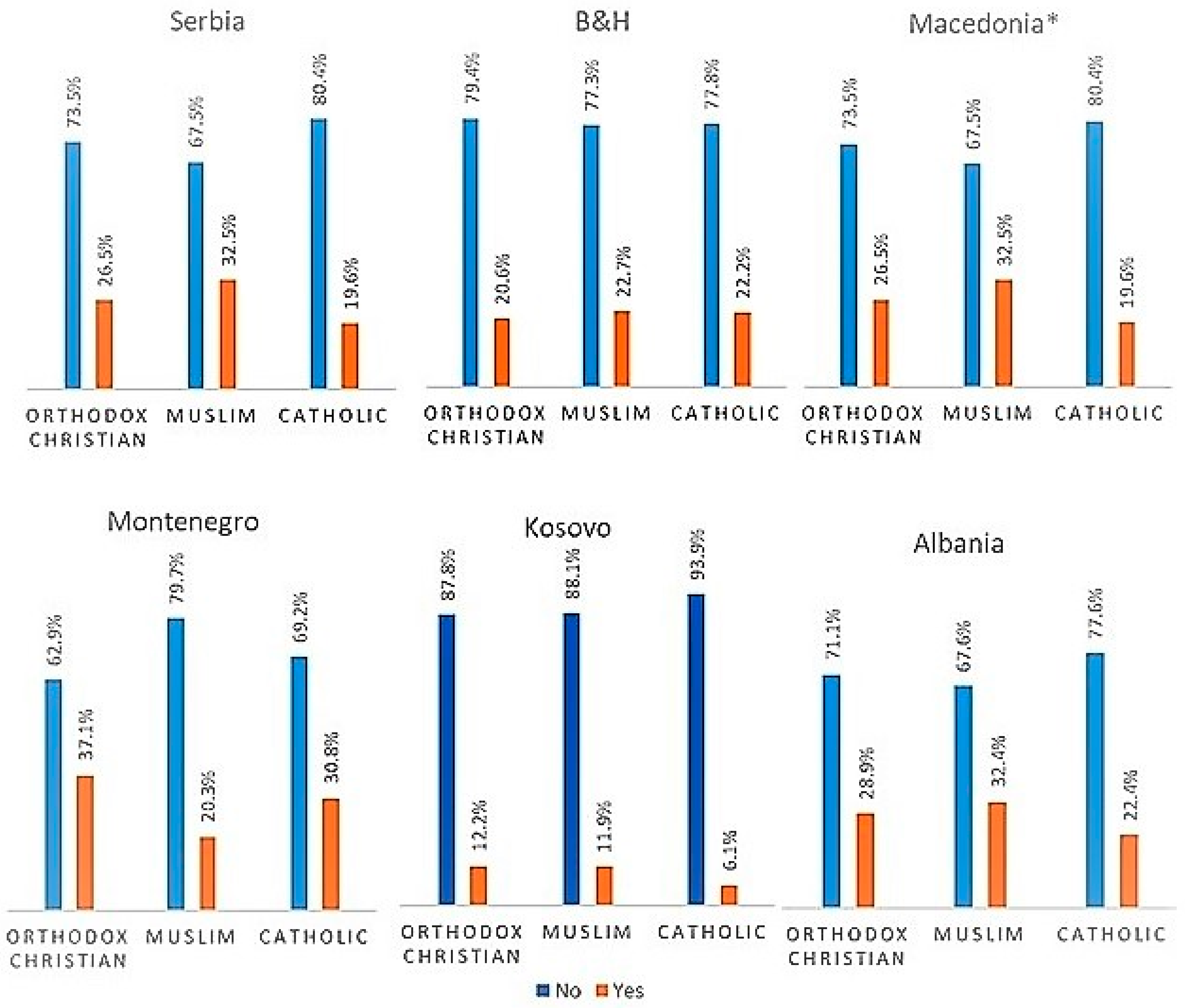

When examining confession and country of origin of respondents together, one can obtain new insights into confessionality and religiosity within certain societies (

Figure 4).

The Chi-square independence test showed that there was a significant difference between religious self-declaration and the confession to which respondents belong in Serbia: χ2 (1026,6) = 16.562, p = 0.011; Macedonia: χ2 (984,4) = 26.571, p < 0.001; Albania: χ2 (703,4) = 10.424, p = 0.03, while this was not the case in the other countries. In Serbia, the most religious were Muslims (almost 70%), while the least religious were Catholics (more than a half). In Macedonia, over 90% of Muslims declared themselves religious, while only 7% say that they were not, compared with almost 20% of Orthodox adherents in this country who declared themselves non-religious. In Serbia and Albania, the number of religious members of all confessions was lower than in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia. Even though the number of religious members was generally lower in the Orthodox population, in Kosovo, 90% of Orthodox adherents declared themselves to be religious. It was obvious that religiosity was affected by the position of religious communities within a country.

The nature of religiosity in the observed countries was further analysed by measuring the level of religious activities such as prayer and visiting temples.

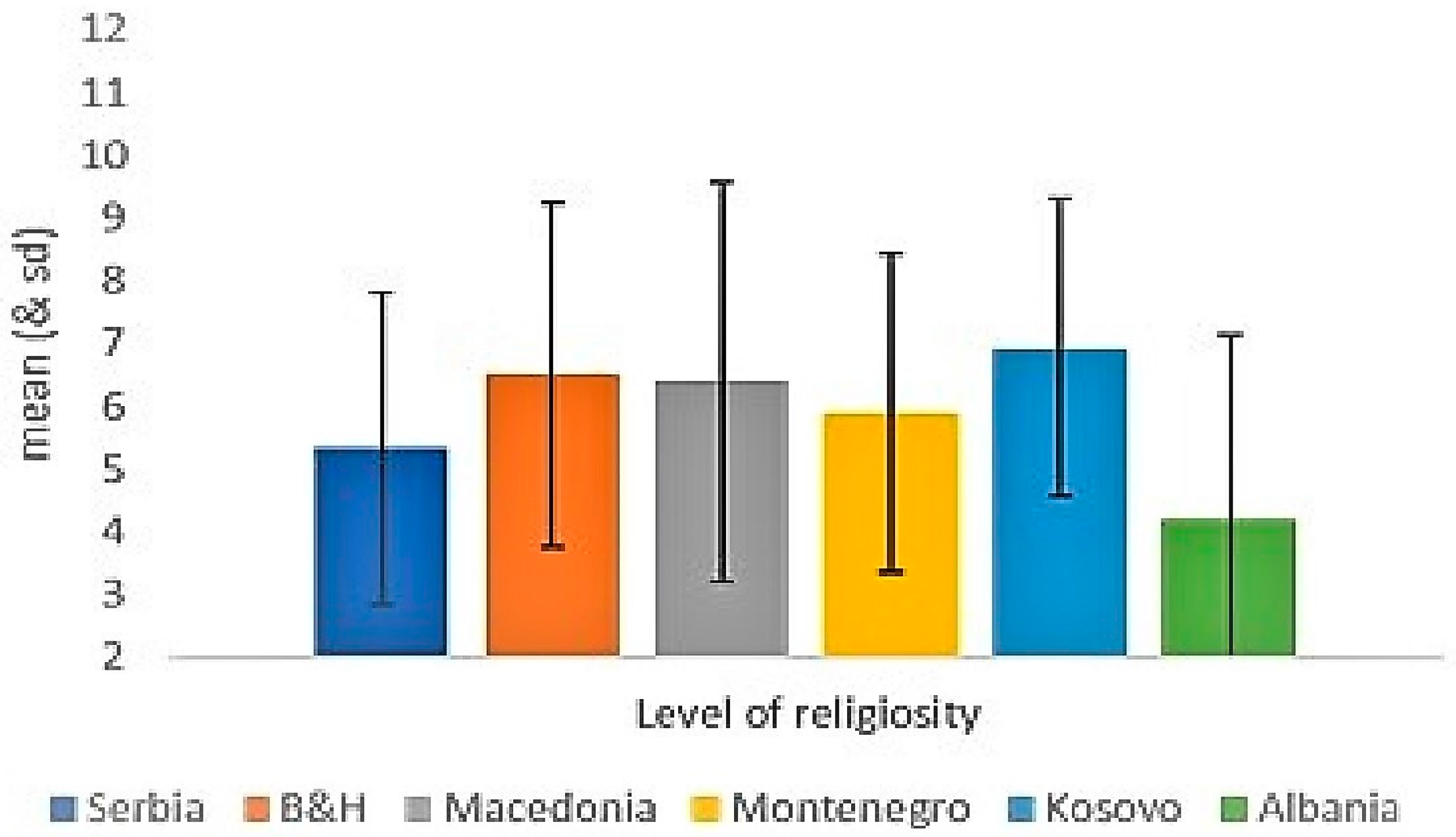

Figure 5 shows the level of religiosity and the differences that exist in the observed countries (in more detail see:

Appendix A,

Table A1).

The level of religiosity was also significantly correlated with the confession to which respondents belong (

Figure 6).

A statistically significant difference was determined between the confessions, F(2,5615) = 64.482,

p < 0.001, while additional post-hoc comparisons showed that both Muslims (m = 6.29, sd = 3.33,

p < 0.001) and Catholics (m = 6.74, sd = 3.07,

p < 0.001) were significantly more religious than Orthodox Christians (m = 5.48, sd = 2.37). There was no significant difference between Muslims and Catholics with regard to the level of religiosity. Orthodox Christians had the lowest level of religious practices, which had already been established in various studies (

PRC 2017); however, another important finding was that it has been growing in those countries where Orthodox adherents are a minority (for more detail see

Appendix A,

Table A2).

However, what is specific for the region in question and in accordance with our previous statements, is the fact that these activities also possess an intra-state dynamic. Namely, the level of religious practices rises or falls not only on the basis of belonging to a religion or a confession but also in relation to the extent of these activities at the state level, as well as in relation to the position of a community—as a minority or a majority—and the relations between religious communities within a country. With this in mind, the level of these religious practices is the highest among the Catholic and Orthodox populations in Kosovo, followed by Muslims in Macedonia, where both of these communities form a minority (

Figure 7).

The two-way analysis of variance of different groups was used to explore the influence of the country of respondents’ origin and the confession to which they belong on the level of religiosity. All influences were statistically significant at the level of p < 0.001. Furthermore, the influence of the interaction between the country of origin and the confession was statistically significant as well, F(12,5623) = 30.165, p < 0.001. In order to examine the influence of this interaction, we performed an analysis of simple effects (a one-way ANOVA for each country separately), which showed that belonging to a certain confession affects the level of religiosity in the majority of countries.

The analysis showed that there was a significant influence of belonging to a certain confession on the level of religiosity in Serbia, F(2,999) = 3.933,

p < 0.020, however, the Games-Howell post-hoc test did not show any significant difference between the members of different confessions. The situation was similar when it came to Montenegro, where the analysis showed a statistically significant difference, F(2,762) = 3.027,

p < 0.049, while the post-hoc test did not point to any specific difference between the groups. Contrary to this, the analysis showed that in Bosnia and Herzegovina there was a statistically significant difference in the level of religiosity between different confessions, F(2,1145) = 26.034,

p < 0.001, and between all of the groups at that—Catholics (m = 7.51, sd = 2.87) were significantly more religious than both Muslim (m = 6.82, sd = 2.12) and Orthodox believers (m = 5.86, sd = 2.45), while Muslims were significantly more religious than Orthodox adherents. The analysis further showed that there was a statistically significant difference between the members of different confessions in Macedonia as well, F(2,983) = 262.455,

p < 0.001, i.e., Muslims (m = 9.21, sd = 2.71) in Macedonia were significantly more religious than the Orthodox population (m = 5.15, sd = 2.99). The situation in Albania was the opposite, with the analysis showing that there was a statistically significant difference between the members of different confessions, F(2,879) = 17.408,

p < 0.001, both between Muslims (m = 4.01, sd = 2.14) and Orthodox believers and Muslims and Catholics (m = 5.53, sd = 3.37), where Orthodox and Catholic believers were significantly more religious than Muslims. As far as Kosovo is concerned, the analysis showed that there was no statistically significant difference between the members of different confessions with regard to the level of religiosity (

p < 0.066) (

Appendix A,

Table A3). All the data corroborate the hypothesis that the level of religiosity of the members of certain religious communities is affected by their position and social context.

In Serbia, Macedonia, and Montenegro the most numerous were Orthodox believers, while in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania, and Kosovo the dominant group was Muslims. The members of the Catholic confession were most present in Bosnia and Herzegovina (even though it was a case of a smaller community than the Muslim and the Orthodox ones) and least present in Macedonia. Protestants were somewhat significantly present only in Serbia (1.6%).

The above analyses show that respondents from Albania were significantly less religious than respondents from all the other countries. Serbia was also characterised by a significantly lower level of religiosity compared with all the other countries, excluding Albania. The respondents from Kosovo were significantly more religious than the populations of the other countries. Bosnia and Herzegovina were characterised by a higher level of religiosity in comparison with Serbia, Montenegro, and Albania. Montenegrins were significantly more religious only when compared with Serbs and Albanians, while in relation to the other countries they were characterised by a significantly lower level of religiosity. When observing the influence of confession on the level of religiosity, both Muslims and Catholics were significantly more religious than Orthodox adherents. In Macedonia, Muslims were significantly more religious than Orthodox believers, while the situation was the opposite in Albania—Orthodox and Catholic believers were significantly more religious than Muslims. This result indicates the existence of “intrastate dynamics”, a generally lower or higher level of religiosity, as well as the influence of the position of a religious group (minority or majority) on the level of religiosity.

2.2. Religion and Attitudes toward Informal Economic Practices

Taking into consideration the nature of attitudes as relatively stable structures, we analysed the attitudes that (do not) justify engaging in informal practices, mentioned in the introductory methodological section of this paper and correlated them with the characteristics of religiosity (self-declared religiosity and level of religiosity) of our respondents. We believe that the existence of certain attitudes can be an indicator of potential behaviours in the observed societies.

2.2.1. Confession or Religion as a Factor of Justifying Informal Practices

In further analysis, we will determine the connection between one’s confessional belonging and religiosity, on the one hand, and attitudes toward informal economic practices, on the other. Belonging to a specific confession or religion (Orthodoxy, Catholicism, Islam)

10 was analysed as a factor justifying these practices.

The first finding was that attitudes towards “using informal connections” to perform various activities were a very frequent practice in these transitional societies. Traditional societies are based on traditional support networks but also on new ones grounded in political networking. In the entire sample, a specific confession or religion played an important role in justifying such practices (

Figure 8).

Generally, the degree of justification for such a practice was very low, yet the analysis of variance confirmed the existence of a statistically significant difference in the level at which the members of different confessions justify using connections and acquaintances for getting things done, F(2,5777) = 95,901,

p < 0.001. A post-hoc test further showed that there was a significant difference in the scores of all three groups of respondents. Namely, Orthodox believers condoned this practice to the greatest extent (m = 2.44, sd = 1.31), followed by Catholics (m = 2.22, sd = 1.28), with the lowest degree of justification found in Muslims (m = 1.96, sd = 1.27). In Muslims, this phenomenon can be linked to the demand for “fair-play”, i.e., the behaviour that is “halal”, being important, where using one’s connections to achieve a disloyal advantage certainly does not belong to such behaviour (

Appendix A,

Table A4).

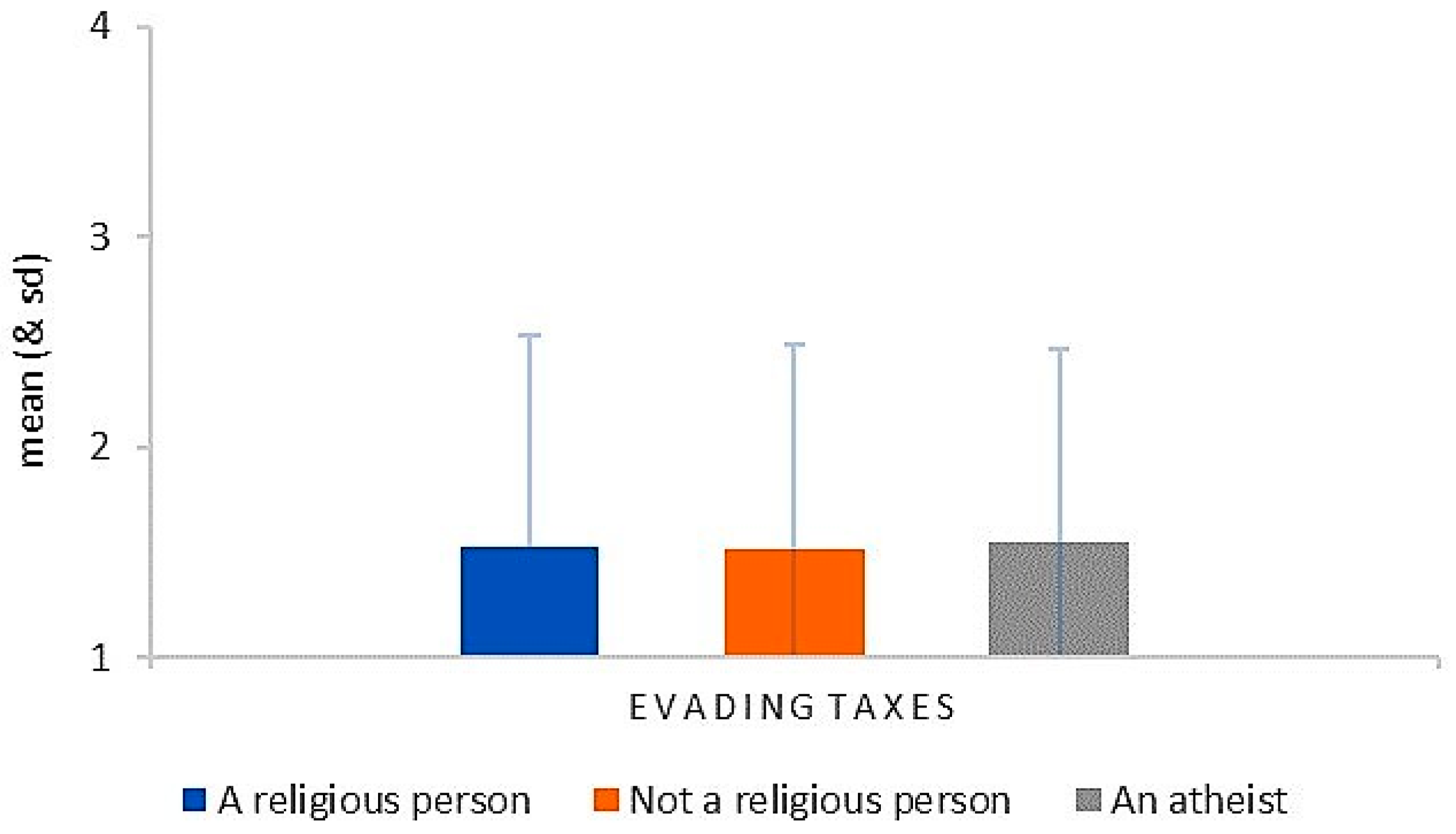

The second observed attitude was regarding tax evasion (

Figure 9).

The one-way analysis of variance indicated a statistically significant difference in the level at which the members of different confessions justify tax evasion, F(2,5755) = 7.051,

p = 0.001. Additional comparisons using the Games-Howell test showed that Muslims (m = 1.48, sd = 0.94) justified the practice of evading taxes to a statistically much less significant degree both in relation to the Orthodox (m = 1.57, sd = 1.03) and the Catholic populations (m = 1.63, sd = 0.99) (

Appendix A,

Table A5). This phenomenon can also be linked to the social teachings that prefer those actions that are “halal”.

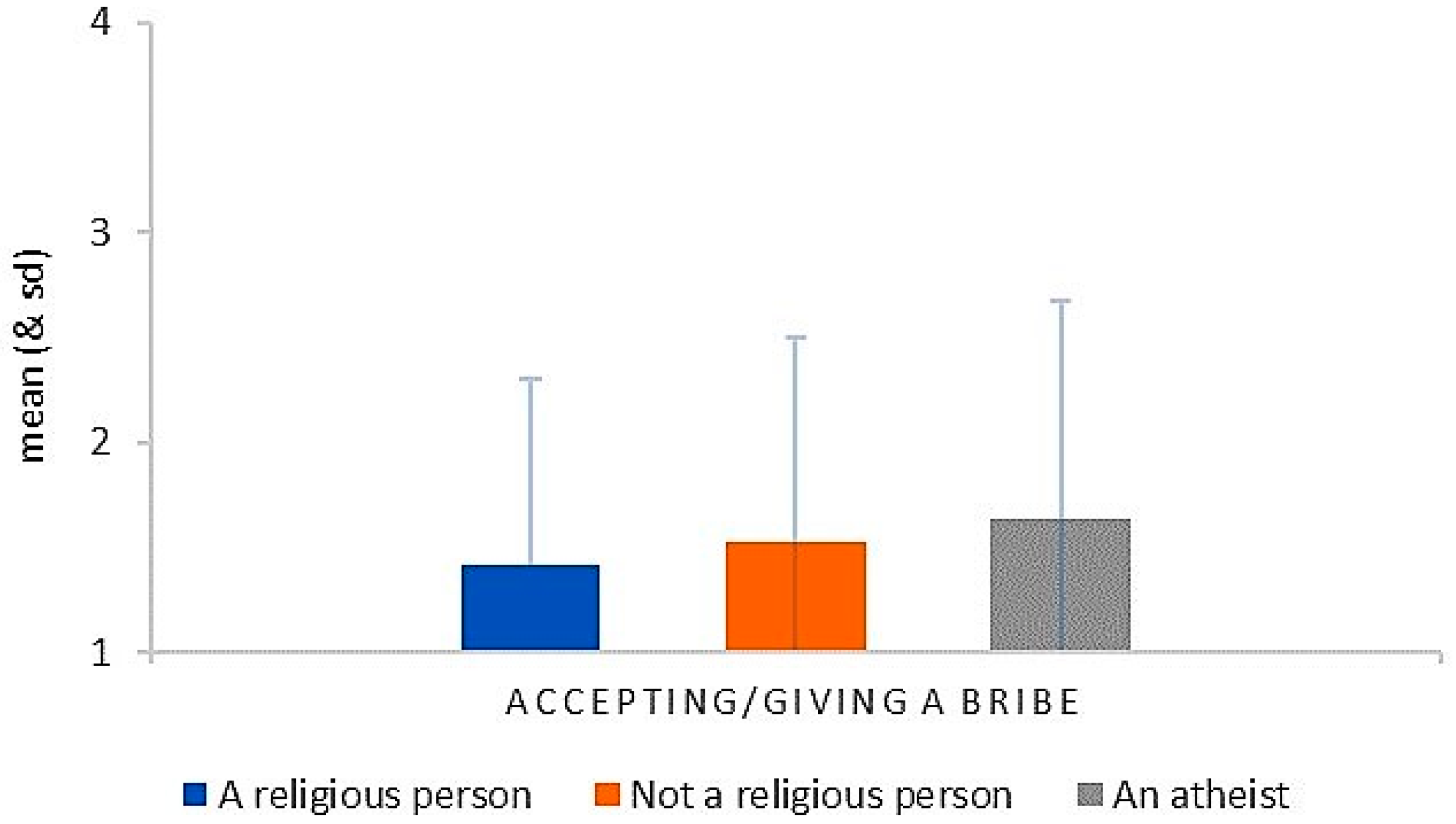

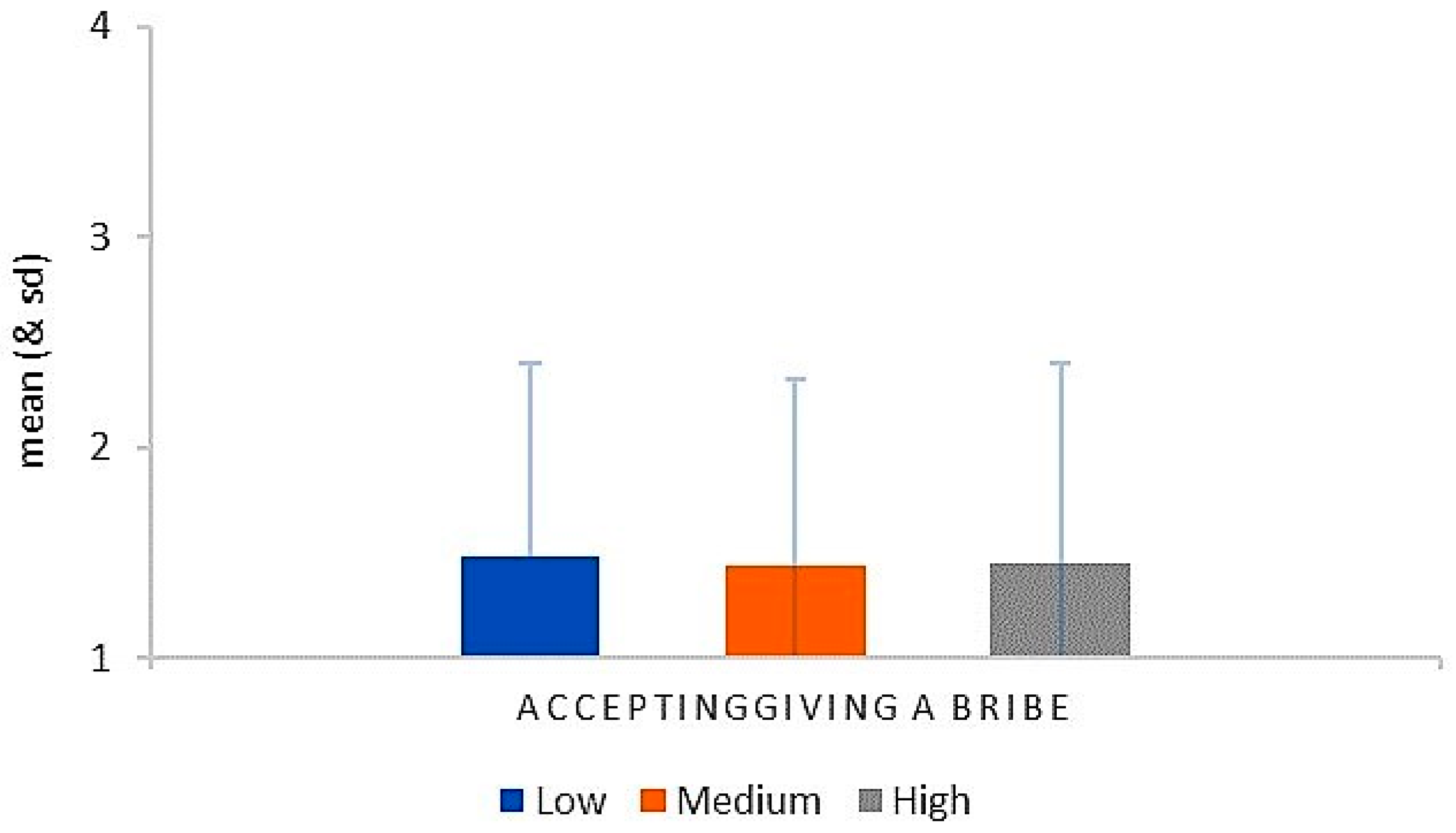

Figure 10 shows the attitudes towards the approval of accepting a bribe with regard to a respondent’s confession.

The analysis of variance results showed that there was a statistically significant difference in the level at which respondents of different confessions justified accepting/giving a bribe, F(2,5781) = 8.511,

p < 0.001. Additional comparisons performed by using the Games-Howell test showed that Catholics (m = 1.67, sd = 1.03) condoned this practice to a greater extent than both Orthodox believers (m = 1.46, sd = 0.91) and Muslims (m = 1.44, sd = 0.91). Between Orthodox and Muslim believers there was no significant difference (

Appendix A,

Table A6). The fact that the number of Catholics in the sample was extremely small, and that the number of those who condoned this practice was even smaller, raises doubts about this finding, making the one that relates to there being no difference in the justification or condemnation of the use of bribes between Orthodox and Muslim believers more significant. All in all, there was almost a unanimous disapproval of this illegal practice among our respondents, regardless of their confessional belonging.

The findings show that confession was correlated with justifying illegal and illegitimate practices and that Muslims condoned these practices to a lesser extent than others.

Significant differences were found regarding the level of justifying the use of connections and acquaintances for getting things done between respondents of different confessions. Orthodox believers condoned this practice to the highest degree, followed by Catholics, while Muslims were the ones who approved of this practice to the lowest degree. Muslims also condoned the practice of tax evasion to a significantly lesser extent, both in relation to the Orthodox and the Catholic population. Catholics were the ones who condoned this practice to a much greater extent than both Orthodox adherents and Muslims. No significant difference was determined between Orthodox adherents and Muslims here.

Our findings corroborate the assumption that the social teachings of Islam on behaviour in the economic sphere contributes to such attitudes towards informal practices among its respondents, while the generalised attitudes of Catholics and especially the complete neglect of this sphere in the Orthodox population favours more liberal attitudes of members of these confessions towards practices that are categorised as illegitimate and illegal.

2.2.2. The Influence of Self-Declared Religiosity on Justifying Informal Practices

As already mentioned, in the countries that were the subject of this analysis, there exists a phenomenon of confessional identification that was not accompanied by an appropriate religiosity, thus, giving rise to a gap between those who declare themselves believers of one religion and those who speak of themselves as religious persons (belonging without believing, (

Davie 2005)). This is why the data on self-declared religiosity and the level of religiosity were taken into account as a separate factor of the (dis)approval of informal practices.

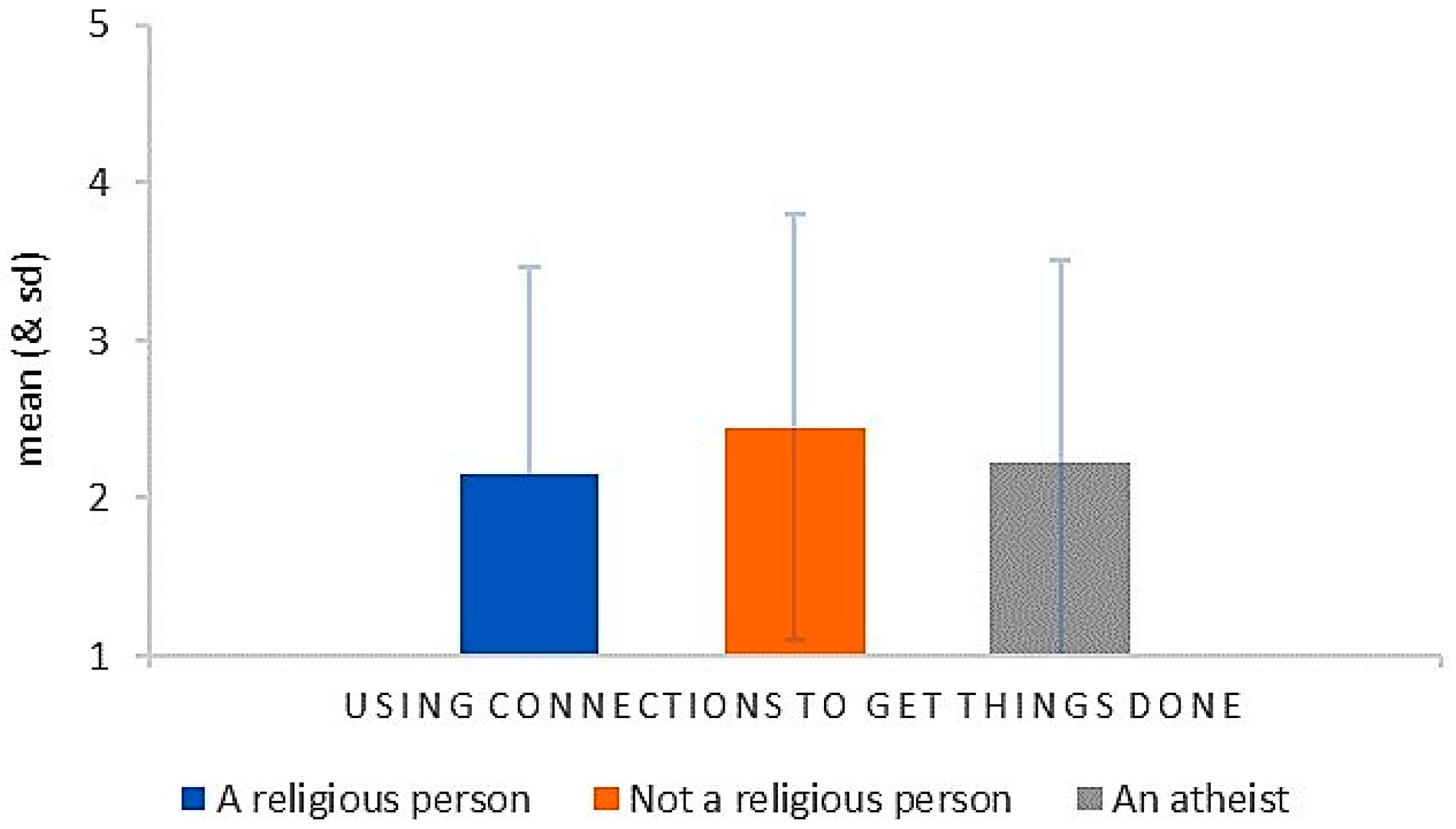

The one-way analysis of variance indicated a statistically significant difference in the level of justifying the use of informal connections and acquaintances in order to “get a job done” between respondents of different self-declared religiosities, i.e., those that declared themselves religious, non-religious, or atheist, F(2,5419) = 20.475,

p < 0.001 (

Figure 11). Additional comparisons showed that non-religious persons (m = 2.45, sd = 1.31) justified this practice to a statistically significantly lower degree than religious persons (m = 2.16, sd = 1.31) and atheists (m = 2.23, sd = 1.29), while no significant difference was observed between religious persons and atheists (

Appendix A,

Table A7). Such a finding can, to some extent, be understood in terms of the established practice, in these societies, in which things get done outside institutions and through traditional connections (family, fellow citizens, members of the same confession) (

Cvejić 2016); particularly if one bears in mind that religious people are usually more traditional than non-religious people, which is where one could look for an explanation for the obtained data. Believers in this region mainly fall under the type of traditional believers, with the number of those church-convicted being much smaller (

Gavrilović 2017;

Abazović 2015).

When it comes to justifying tax evasion and religious self-declaration (

Figure 12), the analysis of variance did not show any statistically significant difference between religious, non-religious and atheist respondents F(2,5399) = 0.194,

p = 823 (

Appendix A,

Table A8) and as can be seen in the graph, the degree of justification of this practice was very low among all respondents.

The next practice whose justification was observed in relation to the self-religious declaration was accepting/giving a bribe (

Figure 13).

The one-way analysis of variance indicated a statistically significant difference in the level at which the respondents who self-declared differently on the issue of religiosity justified accepting/giving a bribe, F(2,5427) = 13.945,

p < 0.001. Additional comparisons showed that religious persons (m = 1.42, sd = 0.88) approved of this practice to a statistically significantly lower degree compared with both non-religious persons (m = 1.53, sd = 0.97) and atheists (m = 1.64, sd = 1.03). No significant difference was observed between religious persons and atheists (

Appendix A,

Table A9).

When examining the use of connections and acquaintances to perform certain activities, non-religious persons justified this practice to a significantly lower degree than religious persons. As far as tax evasion is concerned, there were no differences, while religious persons justified the practice of accepting or giving a bribe to a significantly lower degree.

2.2.3. The Influence of Level of Religiosity on Justifying Informal Economic Practices

The following segment will present the observed difference in approving of, i.e., justifying, informal practices in relation to the level of religiosity.

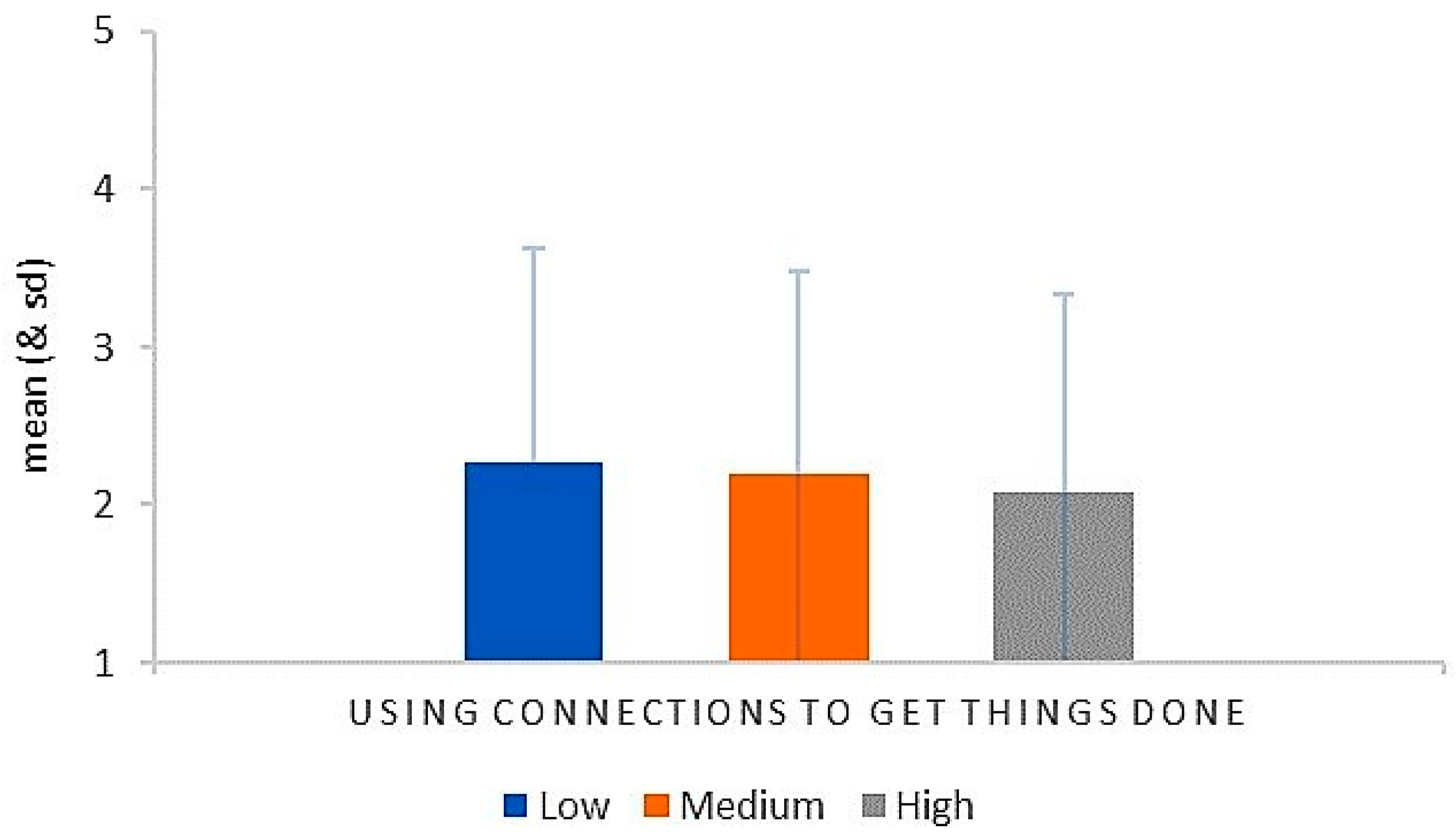

Figure 14 shows the observed differences in relation to the approval of the practice of using connections and acquaintances to perform certain activities.

When it comes to the level of justifying the use of connections and acquaintances to get things done, the analysis of variance indicated a statistically significant difference, F(2,5630) = 8.808,

p < 0.001, between the respondents characterised by different levels of religiosity, while the post-hoc tests showed that the respondents characterised by a high level of religiosity (m = 2.08, sd = 1.26) approved of this practice to a statistically significantly lower degree than the other two groups of respondents, both those characterised by a medium level of religiosity (m = 2.19, sd = 1.29) and those characterised by a low level of religiosity (m = 2.27, sd = 1.35) (

Appendix A,

Table A10). This correlation is something that could be expected if one starts from the assumption that there is a link between religious practice and moral judgement.

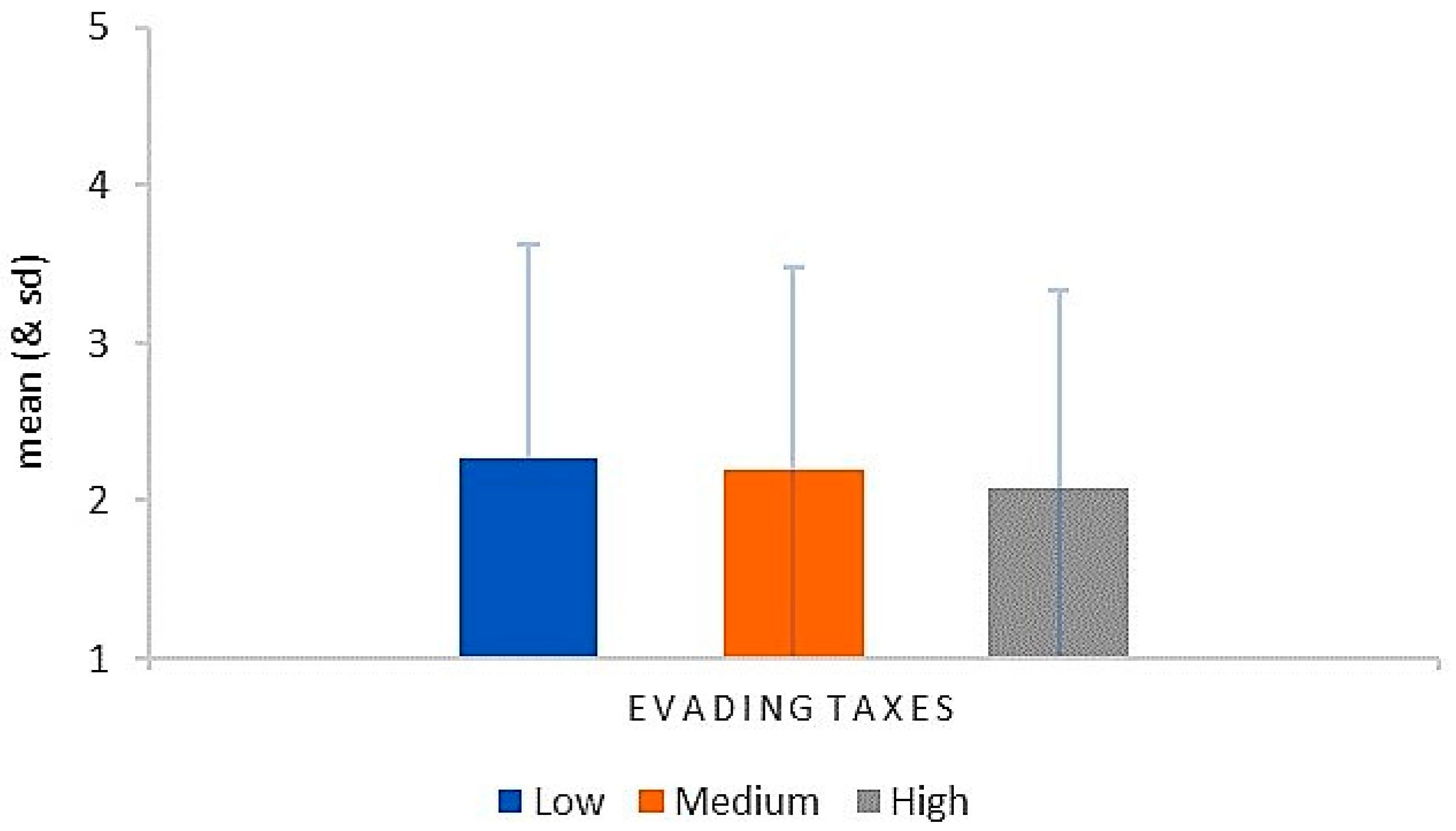

When it comes to the level of religiosity and justifying tax evasion, the results are shown in

Figure 15.

The analysis of variance indicated a statistically significant difference in the level at which respondents characterised by different levels of religiosity justified tax evasion, F(2,5613) = 5.430,

p = 0.004. Additional comparisons using the Games-Howell test showed that respondents characterised by a low level of religiosity (m = 1.48, sd = 0.95) approved of this practice to a statistically significantly lower degree in relation to the other two groups of respondents, those characterised by a medium level of religiosity (m = 1.56, sd = 1.01) and those characterised by a high level of religiosity (m = 1.59, sd = 1.04) (

Appendix A,

Table A11). This could, perhaps, be interpreted from the perspective of Stark’s (2001) findings that show that participation in rituals is not the only indicator of type of religiosity and that mere participation does not correlate with moral judgement but that the manner in which God is imagined and other aspects of religious awareness do (our variable was composed of two elements of religious practice).

When it comes to accepting/giving a bribe with regard to the level of religiosity, the results are shown in the following graph (

Figure 16).

The analysis of variance showed that there was no statistically significant difference in the level at which respondents characterised by different levels of religiosity approved of accepting/giving a bribe, F(2,5636) = 960,

p = 383 (

Appendix A,

Table A12). This practice was justified by an extremely low percentage of all respondents.

The results of the analyses in this segment show that those respondents characterised by a high level of religiosity approved of the practice of using connections to get things done to a statistically significantly lower degree compared to the other two groups of respondents, those characterised by a medium level of religiosity and those characterised by a low level of religiosity. Contrary to this, respondents characterised by a low level of religiosity approved of the practice of tax evasion to a statistically significantly lower degree in relation to the other two groups of respondents, those characterised by a medium level of religiosity and those characterised by a high level of religiosity. These findings could be in agreement with Stark’s (2001) findings that show that participation in rituals is not a good indicator of moral judgement or that social context negates the influence of religiosity in concrete cases.

2.2.4. The Influence of the Country and Confession on the Level of Justifying Informal Economic Practices

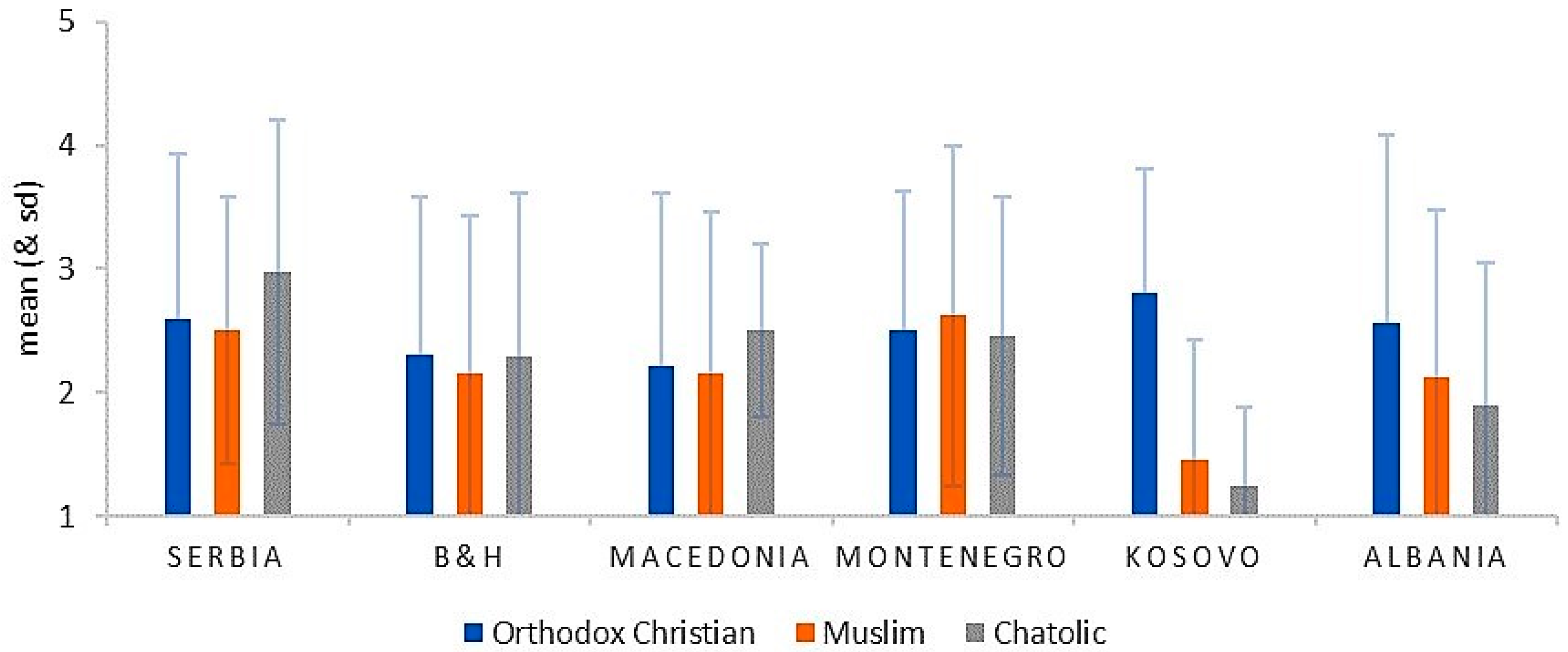

In accordance with our analyses of religiosity that showed that there exists a certain dynamic between belonging to a religion or confession and living in a certain country, further analyses will present the data on the influence of the country and confession on the level of accepting and justifying “the use of connections and acquaintances to get things done”. In line with the previous findings, once again it was confirmed that there is an intrastate dynamic of religiosity of the members of different confessions with regard to them being a minority or a majority (

Figure 17).

The two-way analysis of variance of different groups was used to explore the influence of the country of respondents’ origin and the confession to which they belong on the level at which they justify the use of connections and acquaintances to get things done. All of the influences were statistically significant at the level of

p < 0.001. Furthermore, the influence of the interaction between country of origin and confession proved to be statistically significant, F(10,5762) = 5.771,

p < 0.001 (

Appendix A,

Table A13).

To examine the influence of the interaction, an analysis of simple effects was performed (a one-way ANOVA for each country separately) and it showed that there was a significant influence of belonging to a certain confession on the level of justifying the use of connections and acquaintances to get things done in Kosovo, F(2,893) = 38.889,

p < 0.001, i.e., the level of approving of this practice was significantly much higher among the Orthodox population (m = 2.80, sd = 1.01) compared with both Muslims (m = 1.45, sd = 0.98) and Catholics (m = 1.24, sd = 0.64). Similar results were obtained for Albania, F(2,887) = 4.872,

p < 0.008. Namely, in Albania, the level of justifying this practice was also determined to be significantly higher for Orthodox believers (m = 2.56, sd = 1.53) than for Muslims (m = 2.12, sd = 1.36) and Catholics (m = 1.89, sd = 1.17). As far as the other countries are concerned, the analysis showed that there was no significant influence of belonging to a certain confession on the level of justifying the use of connections and acquaintances to get things done (

Appendix A,

Table A14). The Orthodox population is a minority in the societies where this connection is significant, and that is perhaps why they rely on social networks to achieve their own interests, which leads them to approve of such a practice.

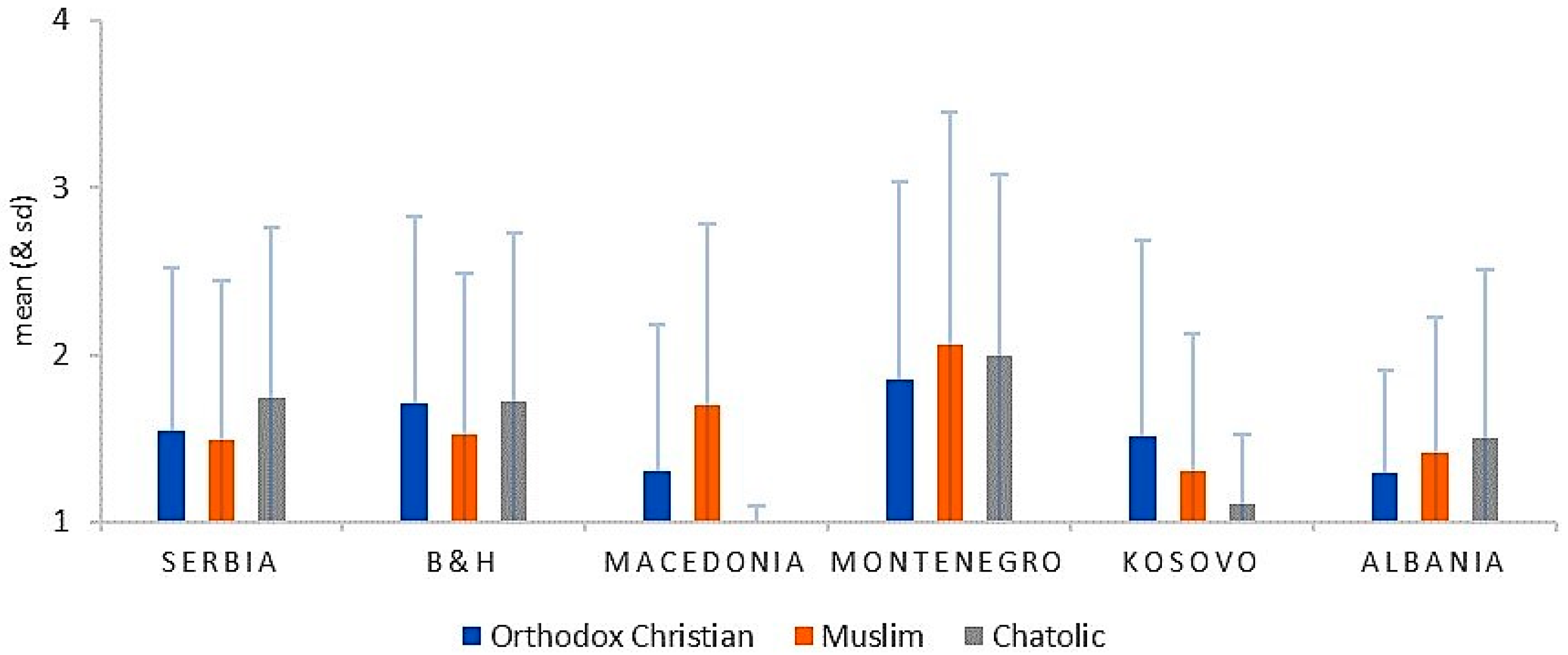

The next measured influence was the influence of the country and confession on justifying “evading (not paying) taxes” (

Figure 18).

The two-way analysis of variance of different groups was used to explore the influence of the country of respondents’ origin and the confession to which they belong on the level at which they justify tax evasion. The statistically significant major influence of the country of origin was determined, F(5,5740) = 8.756,

p < 0.001. Furthermore, the influence of the interaction between the country of origin and the confession proved to be statistically significant, F(10,5762) = 5.771,

p < 0.001 (

Appendix A,

Table A15).

To examine the influence of the interaction, an analysis of simple effects was performed and it showed that there was a significant influence of belonging to a certain confession on the level at which respondents justify tax evasion in Bosnia and Herzegovina, F(2,1166) = 4.915,

p < 0.009, and in Macedonia, F(2,986) = 16.171,

p < 0.001. Additional comparisons using the Games-Howell test showed that in Bosnia and Herzegovina Orthodox believers (m = 1.7128, sd = 1.12307) justified and accepted tax evasion significantly more than Muslims (m = 1.5312, sd = 0.96254). In Macedonia, the situation was completely different. Namely, in this country, Muslims were the ones who justified tax evasion to a significantly higher degree in relation to the Orthodox population (m = 1.7219, sd = 1.01429). There were no significant differences noted in the other countries (

Appendix A,

Table A16). We observed that these communities were minority communities in the said countries and that they were opposed to the state in some manner; thus, their attitude towards not paying taxes can be understood as a proxy for their attitude towards the country itself.

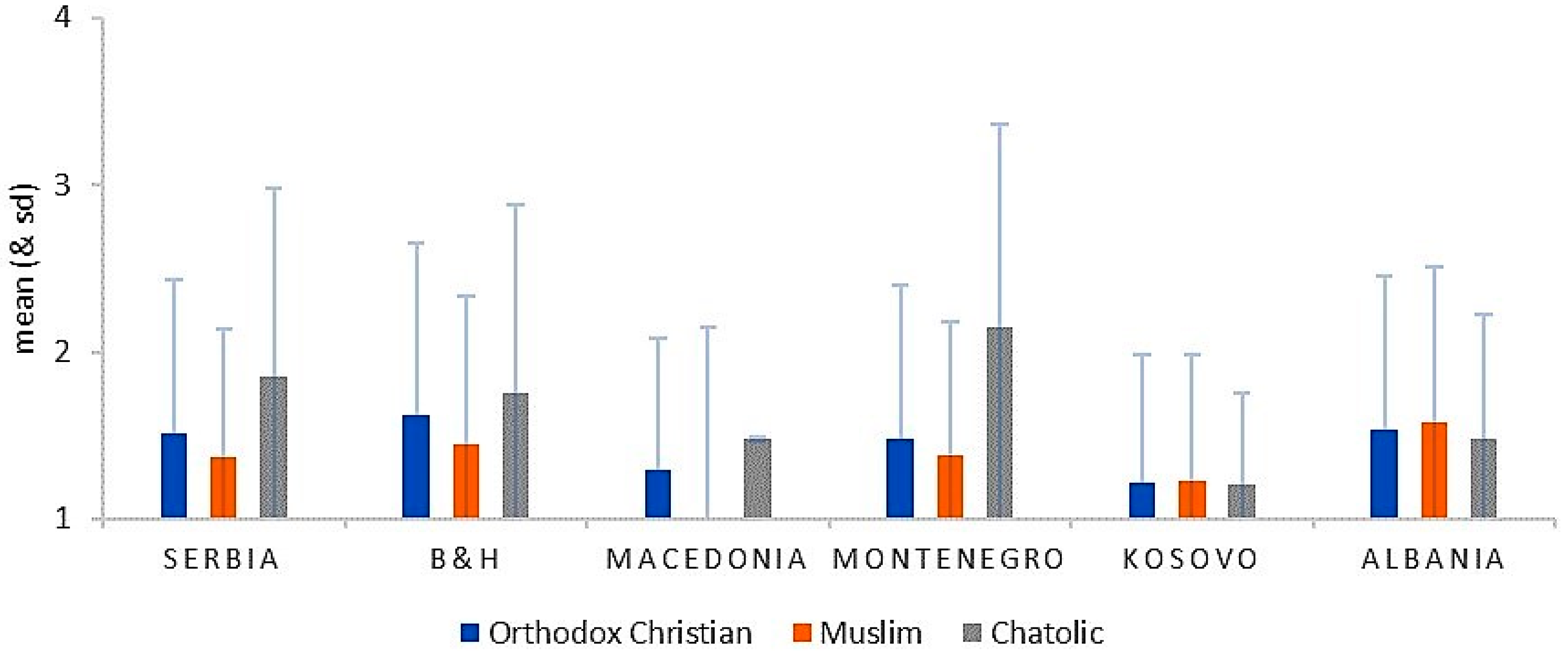

The analysis of the influence of the country and confession on justifying the act of accepting/giving a bribe is presented in

Figure 19.

The two-way analysis of variance of different groups was used to explore the influence of the country of respondents’ origin and the confession to which they belong on the level at which they justify accepting/giving a bribe. The statistically significant major influence of the country of origin was determined, F(5,5766) = 5.229,

p < 0.001. The influence of the interaction between country of origin and confession also proved to be statistically significant, F(10,5766) = 7.122,

p < 0.001 (

Appendix A,

Table A17).

The influence of the interaction was further examined by an analysis of simple effects, i.e., a one-way ANOVA for each country separately, which showed that there was a significant influence of belonging to a certain confession on the level of justifying the act of accepting/giving a bribe in Serbia, F(2,1047) = 3.373,

p < 0.035, Bosnia and Herzegovina, F(2,1171) = 47.213,

p < 0.001, Macedonia, F(2,996) = 26.058,

p < 0.001, and Montenegro, F(2,771) = 4.419,

p < 0.012. Additional comparisons showed that in Bosnia and Herzegovina Muslims (m = 1.45, sd = 0.89) justified accepting/giving a bribe to a significantly lower degree compared with Orthodox (m = 1.61, sd = 1.03) and Catholic believers (m = 1.76, sd = 1.12). In Macedonia, the situation was the complete opposite, i.e., Muslims (m = 1.74, sd = 1.15) were the ones who justify this practice significantly more than the Orthodox population (m = 1.29, sd = 0.79). In the other countries, additional comparisons did not yield any significant differences between members of different confessions (

Appendix A,

Table A18). It appeared that in this case, there was an intrastate dynamic at work as well, i.e., the influence on the position of members of a certain religion, their numbers, minority status, and their current attitude towards the state. There were no patterns when it came to justifying this practice in terms of only one confession.

The influence of the interaction between country of origin and confession proved to be statistically significant for justifying the use of connections as a way to get things done in Kosovo and Albania. In both these cases, Orthodox believers justified the use of connections to a greater extent. This could be a consequence of the higher tolerance among Orthodox believers towards this practice in general but also of the position of minority communities that rely on social networks.

We determined a statistically significant influence of the country of origin and confession on justifying tax evasion in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Orthodox population and in Macedonia in the Muslim population. This sheds a somewhat new light on the generally lower level of justifying such behaviour among Muslims and corroborates the hypothesis that the position of a religious community determines their attitudes.

We also found a statistically significant influence of the interaction between country of origin and confession (Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, Montenegro) regarding the approval of accepting/giving a bribe. In Bosnia and Herzegovina Muslims justified accepting/giving a bribe to a significantly lower degree than both Orthodox and Catholic believers. In Macedonia, the situation was the complete opposite, where Muslims were the ones who justify this practice to a significantly higher degree compared to the Orthodox population. It seems that, in this case, there was an influence of the position of a community in the observed society as well. In all other countries, additional comparisons did not lead to any significant differences between confessions.