Paternity Leave, Father Involvement, and Parental Conflict: The Moderating Role of Religious Participation

Abstract

1. Conceptual Framework

1.1. Paternity Leave

1.2. Paternity Leave, Father Involvement, and Parental Conflict

1.3. Religious Participation, Father Involvement, and Parental Conflict

1.4. Religious Participation as a Moderator

2. Hypotheses

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Paternity Leave

3.3. Religious Participation

3.4. Father Involvement and Parental Relationship Conflict

3.5. Control Variables

3.6. Analytic Strategy

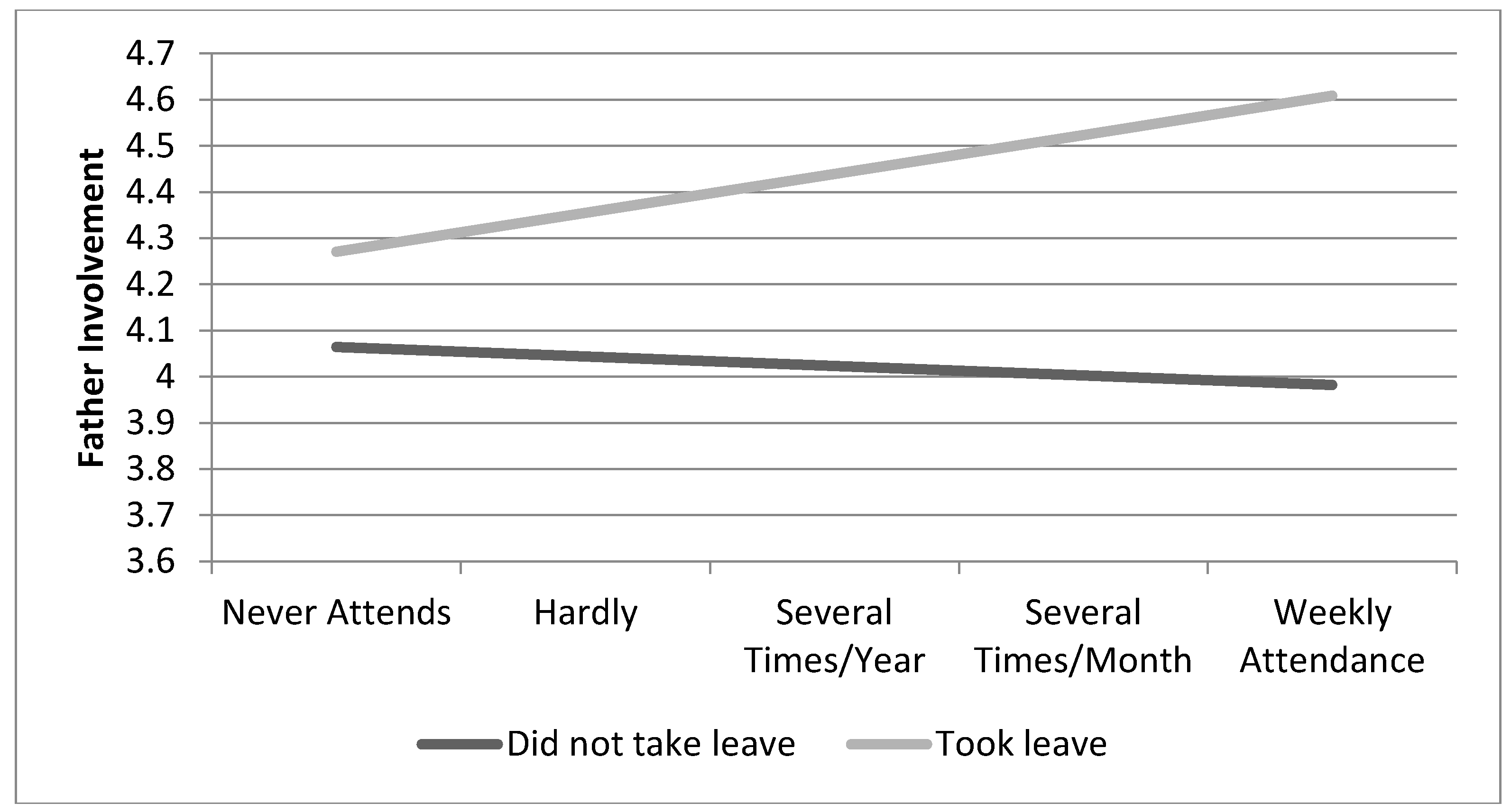

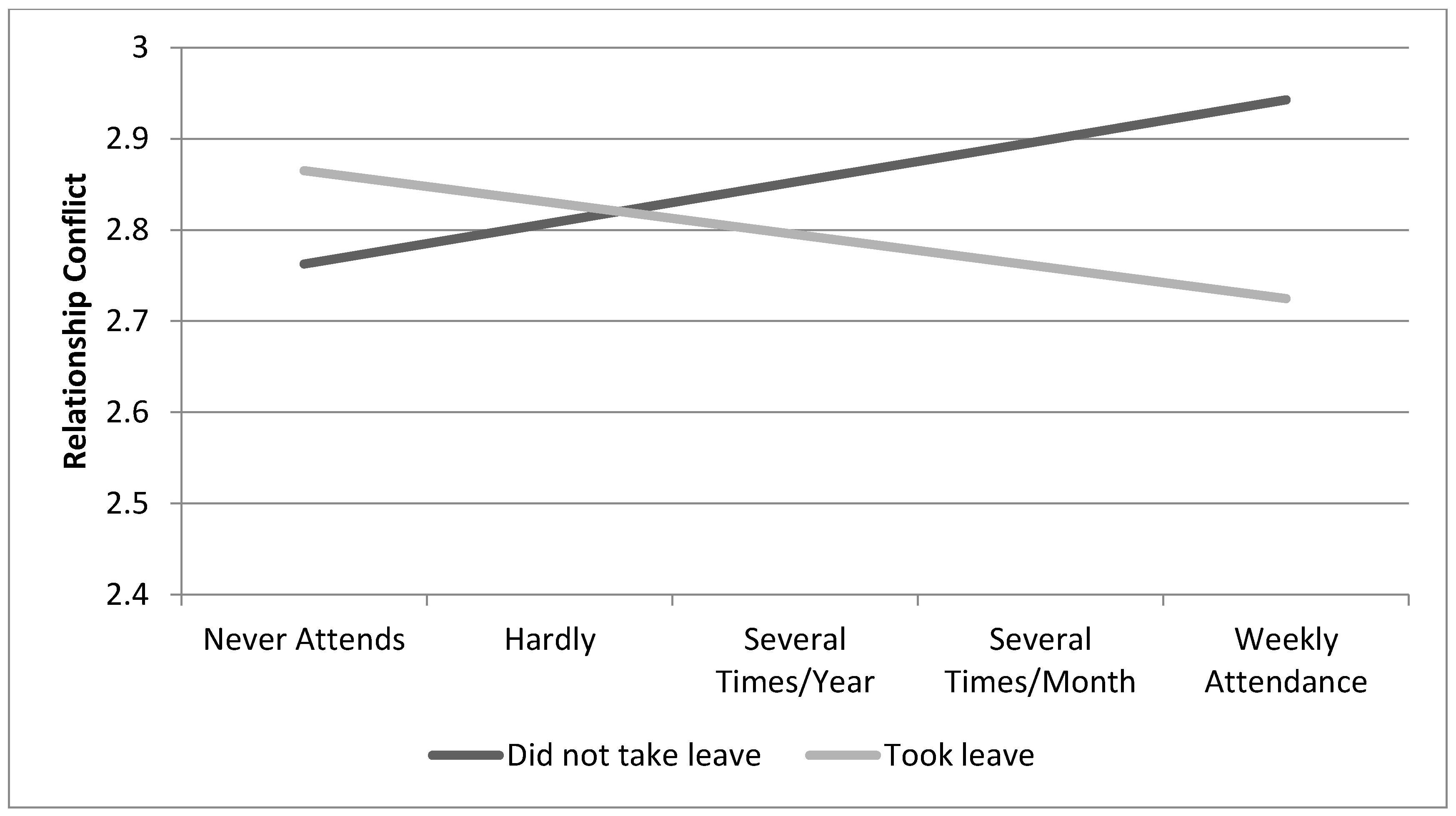

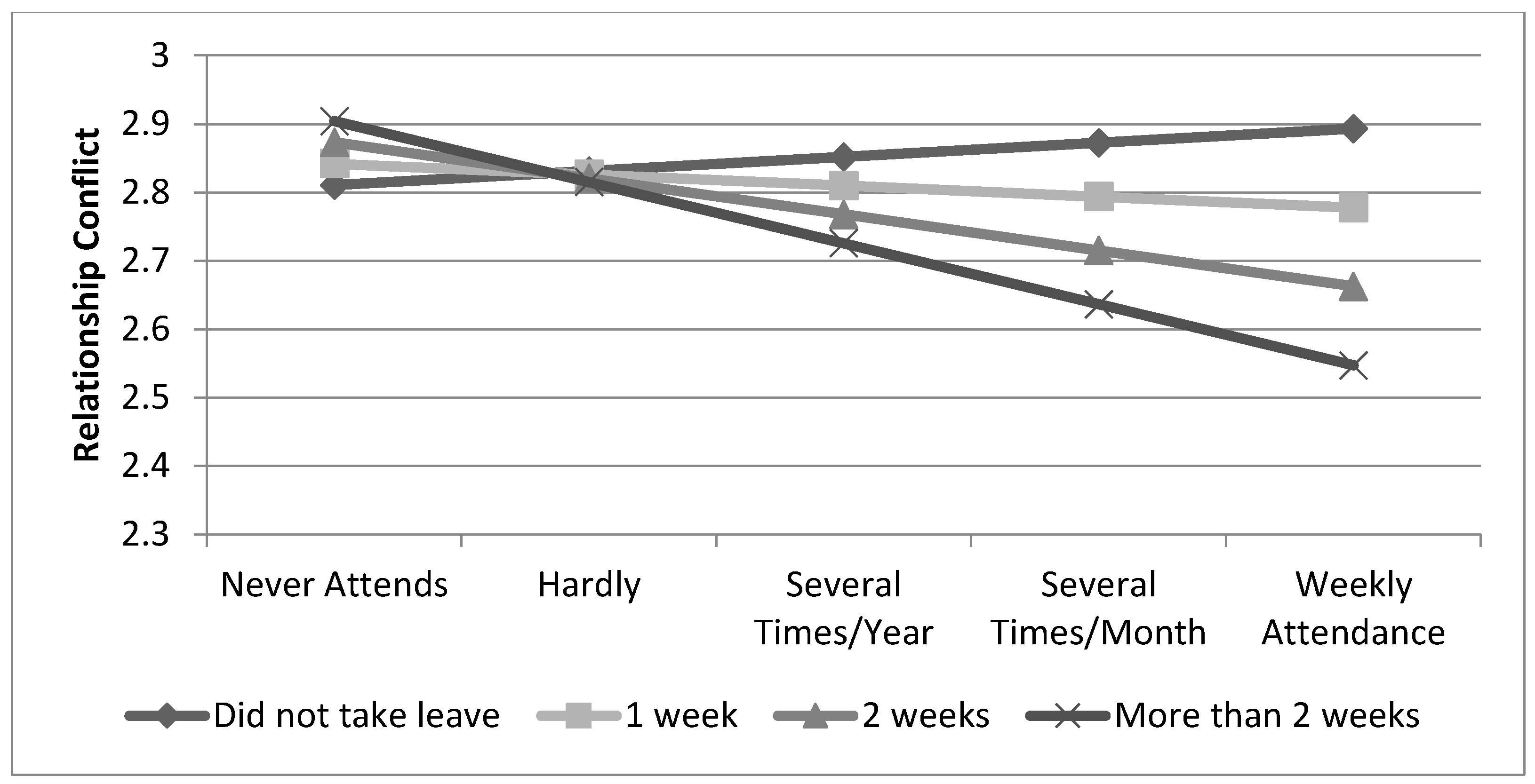

4. Results

5. Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albiston, Catherine, and Lindsey Trimble O’Connor. 2016. Just Leave. Harvard Women’s Law Journal 39: 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Almqvist, Anna-Lena, and Ann-Zofie Duvander. 2014. Changes in Gender Equality? Swedish Fathers’ Parental Leave, Division of Childcare and Housework. Journal of Family Studies 20: 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumann, Kerstin, Ellen Galinsky, and Kenneth Matos. 2011. The New Male Mystique. New York: Families and Work Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowski, John P., and Xiaohe Xu. 2000. Distant Patriarchs or Expressive Dads? The Discourse of Fathering in Conservative Protestant Families. The Sociological Quarterly 41: 465–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birditt, Kira S., Edna Brown, Terri L. Orbuch, and Jessica M. McIlvane. 2010. Marital Conflict Behaviors and Implications for Divorce Over 16 Years. Journal of Marriage and Family 72: 1188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, Sonja, Alison Koslowski, and Peter Moss, eds. 2017. International Review of Leave Policies and Research 2017. Available online: http://www.leavenetwork.org/lp_and_r_reports/ (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Bünning, Mareike. 2015. European Sociological Review 31: 738–48.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2018. Access to Paid Personal Leave, December 2017. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/ebs/paid_personal_leave_122017.htm (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Cabrera, Natasha J., Jay Fagan, and Danielle Farrie. 2008. Explaining the Long Reach of Fathers’ Prenatal Involvement on Later Paternal Engagement. Journal of Marriage and Family 70: 1094–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Call, Vaughn R. A., and Tim B. Heaton. 1997. Religious Influence on Marital Stability. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 36: 382–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, Daniel L., Sarah Hanson, and Andrea Fitzroy. 2016. The Division of Child Care, Sexual Intimacy, and Relationship Quality in Couples. Gender & Society 30: 442–66. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, Daniel L., Amanda J. Miller, and Sharon Sassler. 2018. Stalled for whom? Change in the division of particular housework tasks and their consequences for middle- to low-income couples. Socius 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrère, Sybil, and John Mordechai Gottman. 1999. Predicting Divorce among Newlyweds from the First Three Minutes of a Marital Conflict Discussion. Family Process 38: 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coltrane, Scott, Elizabeth C. Miller, Tracy DeHaan, and Lauren Stewart. 2013. Fathers and the Flexibility Stigma. Journal of Social Issues 69: 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, Carolyn Pape, Philip A. Cowan, Gertrude Heming, Ellen Garrett, William S. Coysh, Harriet Curtis-Boles, and Abner J. Boles, III. 1985. Transitions to Parenthood: His, Hers, and Theirs. Journal of Family Issues 6: 451–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeMaris, Alfred, Annette Mahoney, and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2011. Doing the Scut Work of Infant Care: Does Religiousness Encourage Father Involvement? Journal of Marriage and Family 73: 354–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denton, Melinda Lundquist. 2004. Gender and Marital Decision Making: Negotiating Religious Ideology and Practice. Social Forces 82: 1151–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollahite, David C. 1998. Fathering, Faith, and Spirituality. Journal of Men’s Studies 7: 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucet, Andrea. 2013. Gender Roles and Fathering. In Handbook of Father Involvement: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Edited by Natasha J. Cabrera and Catherine S. Tamis-Lemonda. New York: Routledge, pp. 297–319. [Google Scholar]

- Edgell, Penny. 2006. Religion and Family in a Changing Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, Christopher G., and Jeffrey S. Levin. 1998. The Religion-Health Connection: Evidence, Theory, and Future Directions. Health Education and Behavior 25: 700–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisco, Michelle L., and Kristi Williams. 2003. Perceived Housework Equity, Marital Happiness, and Divorce in Dual-Earner Households. Journal of Family Issues 24: 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, Sally K., and Christian Smith. 1999. Symbolic Traditionalism and Pragmatic Egalitarianism: Contemporary Evangelicals, Families, and Gender. Gender & Society 13: 211–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gerson, Kathleen. 2010. The Unfinished Revolution: How a New Generation Is Reshaping Family, Work, and Gender in America. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grych, John H., and Frank D. Fincham. 1990. Marital Conflict and Children’s Adjustment: A Cognitive-Contextual Framework. Psychological Bulletin 108: 267–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, Linda, and C. Philip Hwang. 2008. The Impact of Taking Parental Leave on Fathers’ Participation in Childcare and Relationships with Children: Lessons from Sweden. Community, Work, and Family 11: 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, Brad, Fred Van Deusen, Jennifer Sabatini Fraone, Samantha Eddy, and Linda Haas. 2014. The New Dad: Take Your Leave. Boston: Boston College Center for Work and Family. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, Juliana, Kim Parker, Nikki Graf, and Gretchen Livingston. 2017. Americans Widely Support Paid Family and Medical Leave, but Differ Over Specific Policies. Washington: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta, Maria C., Willem Adema, Jennifer Baxter, Wen-Jui Han, Mette Lausten, RaeHyuck Lee, and Jane Waldfogel. 2014. Fathers’ Leave and Fathers’ Involvement: Evidence from Four OECD Countries. European Journal of Social Security 16: 308–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killewald, Alexandra. 2013. A Reconsideration of the Fatherhood Premium: Marriage, Coresidence, Biology, and Fathers’ Wages. American Sociological Review 78: 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Valerie. 2003. The Influence of Religion on Father’s Relationships with Their Children. Journal of Marriage and Family 65: 382–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerman, Jacob Alex, Kelly Daley, and Alyssa Pozniak. 2012. Family and Medical Leave in 2012: Technical Report. Cambridge: ABT Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsadam, Andreas, and Henning Finseraas. 2011. The State Intervenes in the Battle of the Sexes: Causal Effects of Paternity Leave. Social Science Research 40: 1611–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusner, Katherine G., Annette Mahoney, Kenneth I. Pargament, and Alfred DeMaris. 2014. Sanctification of Marriage and Spiritual Intimacy Predicting Observed Marital Interactions Across the Transition to Parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology 28: 604–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, Michael E., ed. 2010. How do Fathers Influence Children’s Development? Let me Count the Ways. In The Role of the Father in Child Development, 5th ed. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, Mark G., John H. Grych, and Gregory M. Fosco. 2016. Influences on Father Involvement: Testing for Unique Contributions of Religion. Journal of Child and Family Studies 25: 3247–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, Annette. 2005. Religion and Conflict in Marital and Parent-Child Relationships. Journal of Social Issues 61: 689–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, Annette. 2010. Religion in Families, 1999–2009: A Relational Spirituality Framework. Journal of Marriage and Family 72: 805–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, Annette, Kenneth I. Pargament, Tracey Jewell, Aaron B. Swank, Eric Scott, Erin Emery, and Mark Rye. 1999. Marriage and the Spiritual Realm: The Role of Proximal and Distal Religious Constructs in Marital Functioning. Journal of Family Psychology 13: 321–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, Annette, Kenneth I. Pargament, Nalini Tarakeshwar, and Aaron B. Swank. 2001. Religion in the Home in the 1980s and 1990s: A Meta-Analytic Review and Conceptual Analysis of Links between Religion, Marriage, and Parenting. Journal of Family Psychology 15: 559–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, Annette, Kenneth I. Pargament, Aaron Murray-Swank, and Nichole Murray-Swank. 2003. Religion and the Sanctification of Family Relationships. Review of Religious Research 44: 220–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsiglio, William, and Kevin Roy. 2012. Nurturing Dads: Social Initiatives for Contemporary Fatherhood. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- McGill, Brittany S. 2014. Navigating New Norms of Involved Fatherhood: Employment, Fathering Attitudes, and Father Involvement. Journal of Family Issues 35: 1089–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Partnership for Women and Families. 2018. State Paid Family and Medical Leave Laws, July 2018. Washington, D.C. Available online: http://www.nationalpartnership.org/research-library/work-family/paid-leave/state-paid-family-leave-laws.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2018).

- Nepomnyaschy, Lenna, and Jane Waldfogel. 2007. Paternity Leave and Fathers’ Involvement with their Young Children. Community, Work and Family 10: 427–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palkovitz, Rob. 2002. Involved Fathering and Men’s Adult Development: Provisional Balances. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Pedulla, David S., and Sarah Thébaud. 2015. Can We Finish the Revolution? Gender, Work-Family Ideals, and Institutional Constraint. American Sociological Review 80: 116–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petts, Richard J. 2007. Religious Participation, Religious Affiliation, and Engagement with Children Among Fathers Experiencing the Birth of a New Child. Journal of Family Issues 28: 1139–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petts, Richard J. 2011. Is Urban Fathers’ Religion Important for their Children’s Behavior? Review of Religious Research 53: 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petts, Richard J., and Chris Knoester. 2018. Paternity Leave-Taking and Father Engagement. Journal of Marriage and Family 80: 1144–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petts, Richard J., Chris Knoester, and Qi Li. 2018. Paid Paternity Leave-Taking in the United States. Community, Work & Family 14: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pragg, Brianne, and Chris Knoester. 2017. Parental Leave Usage among Disadvantaged Fathers. Journal of Family Issues 38: 1157–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raub, Amy, Arijit Nandi, Nicolas De Guzman Chorny, Elizabeth Wong, Paul Chung, Priya Batra, Adam Schickedanz, Bijetri Bose, Judy Jou, Daniel Franken, and et al. 2018. Paid Parental Leave: A Detailed Look at Approaches Across OECD Countries. Los Angeles: WORLD Policy Analysis Center. [Google Scholar]

- Rege, Mari, and Ingeborg F. Solli. 2013. The Impact of Paternity Leave on Fathers’ Future Earnings. Demography 50: 2255–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehel, Erin M. 2014. When Dad Stays Home Too: Paternity Leave, Gender, and Parenting. Gender and Society 28: 110–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggman, Lori A., Lisa K. Boyce, Gina A. Cook, and Jerry Cook. 2002. Getting Dads Involved: Father Involvement in Early Head Start and with their Children. Infant Mental Health Journal 23: 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, Lauri A., and Kris Mescher. 2013. Penalizing Men who Request a Family Leave: Is Flexibility Stigma a Femininity Stigma? Journal of Social Issues 69: 322–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkadi, Anna, Robert Kristiansson, Frank Oberklaid, and Sven Bremberg. 2008. Fathers’ Involvement and Children’s Developmental Outcomes: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Acta Paediatrica 97: 153–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steensland, Brian, Jerry Z. Park, Mark D. Regnerus, Lynn D. Robinson, W. Bradford Wilcox, and Robert D. Woodberry. 2000. The Measure of American Religion: Toward Improving the State of the Art. Social Forces 79: 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Sakiko, and Jane Waldfogel. 2007. Effects of Parental Leave and Working Hours on Fathers’ Involvement with their Babies: Evidence from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Community, Work, and Family 10: 409–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, Jean M., W. Keith Campbell, and Craig A. Foster. 2003. Parenthood and Marital Satisfaction: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Marriage and Family 65: 574–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, W. Bradford. 2004. Soft Patriarchs, New Men: How Christianity Shapes Fathers and Husbands. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, W. Bradford, and Nicholas H. Wolfinger. 2008. Living and Loving ‘Decent’: Religion and Relationship Quality among Urban Parents. Social Science Research 37: 828–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, Joan C. 2000. Unbending Gender: Why Family and Work Conflict and What to Do about It. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Joan C., Mary Blair-Loy, and Jennifer L. Berdahl. 2013. Cultural Schemas, Social Class, and the Flexibility Stigma. Journal of Social Issues 69: 209–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfinger, Nicholas H., and W. Bradford Wilcox. 2008. Happily Ever After? Religion, Marital Status, Gender, and Relationship Quality in Urban Families. Social Forces 86: 1311–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | These variables were included in supplementary analyses. Although there were instances in which paternity leave and/or religious participation were associated with these outcomes, the relationship between paternity leave and these outcomes did not vary by religious participation. |

| Variables | M | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | ||||

| Father Involvement | 4.35 | 1.59 | 0 | 7 |

| Relationship Conflict | 2.80 | 0.90 | 1 | 5 |

| Key Variables | ||||

| Paternity Leave | 0.79 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Length of Paternity Leave | 1.07 | 0.78 | 0 | 3 |

| Religious Participation | 1.91 | 1.35 | 0 | 4 |

| Controls | ||||

| Catholic | 0.30 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Conservative Protestant | 0.27 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Mainline Protestant | 0.05 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Other Protestant | 0.18 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Other Religious Affiliation | 0.09 | - | 0 | 1 |

| No Religious Affiliation * | 0.11 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Married * | 0.34 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Cohabiting | 0.41 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Nonresident | 0.25 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Number of Other Children | 1.02 | 1.18 | 0 | 5 |

| Education | 2.31 | 1.00 | 1 | 4 |

| Works Part-Time | 0.08 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Works Full-Time * | 0.49 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Works more than Full-Time | 0.43 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Professional Occupation | 0.17 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Labor Occupation * | 0.49 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Sales Occupation | 0.08 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Service Occupation | 0.24 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Other Occupation | 0.02 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Income | 3.36 | 2.18 | 0 | 8 |

| Mother’s Income | 1.17 | 1.63 | 0 | 4 |

| Age | 28.18 | 6.93 | 18 | 57 |

| White * | 0.27 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Black | 0.42 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Latino | 0.26 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Other Race | 0.05 | - | 0 | 1 |

| U.S. Native | 0.84 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Child Age | 15.60 | 3.90 | 5 | 30 |

| Child is Male | 0.52 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Length of Maternity Leave | 2.46 | 3.14 | 0 | 12 |

| Positive Father Attitudes | 3.76 | 0.40 | 1 | 4 |

| Engaged Father Attitudes | 0.66 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Traditional Gender Attitudes | 0.39 | - | 0 | 1 |

| Prenatal Involvement | 0.93 | - | 0 | 1 |

| W1 Relationship Conflict | 1.40 | 0.35 | 1 | 3 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE b | B | SE b | b | SE b | b | SE b | |

| Paternity Leave-Taking | 0.40 | 0.09 *** | 0.21 | 0.14 | ||||

| Length of Paternity Leave | 0.23 | 0.04 *** | 0.16 | 0.08 * | ||||

| Religious Participation | 0.06 | 0.03 * | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 * | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Catholic | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.13 |

| Conservative Protestant | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.13 |

| Mainline Protestant | −0.04 | 0.18 | −0.04 | 0.18 | −0.04 | 0.18 | −0.04 | 0.18 |

| Other Protestant | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.13 |

| Other Religious Affiliation | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.16 |

| Cohabiting | −0.10 | 0.09 | −0.09 | 0.09 | −0.09 | 0.09 | −0.08 | 0.09 |

| Nonresident | −0.72 | 0.11 *** | −0.71 | 0.11 *** | −0.71 | 0.11 *** | −0.71 | 0.11 *** |

| Number of Other Children | −0.09 | 0.03 ** | −0.09 | 0.03 ** | −0.09 | 0.03 ** | −0.09 | 0.03 ** |

| Education | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.04 |

| Works Part-Time | −0.21 | 0.13 | −0.21 | 0.13 | −0.22 | 0.13 | −0.21 | 0.13 |

| Works more than Full-Time | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.00 | 0.08 |

| Professional Occupation | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| Sales Occupation | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.13 |

| Service Occupation | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.08 |

| Other Occupation | −0.22 | 0.26 | −0.23 | 0.26 | −0.24 | 0.26 | −0.25 | 0.26 |

| Income | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Mother’s Income | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Age | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Black | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| Latino | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.11 |

| Other Race | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.18 |

| U.S. Native | 0.35 | 0.11 ** | 0.35 | 0.11 ** | 0.35 | 0.11 ** | 0.35 | 0.11 ** |

| Child Age | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Child is Male | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Length of Maternity Leave | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Positive Father Attitudes | 0.26 | 0.08 ** | 0.26 | 0.08 ** | 0.25 | 0.08 ** | 0.25 | 0.08 ** |

| Engaged Father Attitudes | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| Traditional Gender Attitudes | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Prenatal Involvement | 0.59 | 0.14 *** | 0.59 | 0.14 *** | 0.61 | 0.14 *** | 0.61 | 0.14 *** |

| Leave-Taking × Religious Participation | 0.11 | 0.06 † | ||||||

| Length of Leave × Religious Participation | 0.04 | 0.03 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.11 | ||||

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE b | b | SE b | b | SE b | b | SE b | |

| Paternity Leave-Taking | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.08 | ||||

| Length of Paternity Leave | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | ||||

| Religious Participation | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Catholic | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.02 | 0.08 |

| Conservative Protestant | −0.09 | 0.08 | −0.10 | 0.08 | −0.09 | 0.08 | −0.09 | 0.08 |

| Mainline Protestant | −0.09 | 0.11 | −0.10 | 0.11 | −0.09 | 0.11 | −0.10 | 0.11 |

| Other Protestant | −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.03 | 0.09 |

| Other Religious Affiliation | −0.12 | 0.09 | −0.13 | 0.09 | −0.12 | 0.09 | −0.13 | 0.09 |

| Cohabiting | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.06 |

| Nonresident | 0.15 | 0.06 * | 0.15 | 0.06 * | 0.15 | 0.06* | 0.15 | 0.06* |

| Number of Other Children | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Education | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Works Part-Time | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Works more than Full-Time | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.06 |

| Professional Occupation | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.07 |

| Sales Occupation | −0.13 | 0.07 † | −0.13 | 0.07 † | −0.13 | 0.07 † | −0.14 | 0.07 † |

| Service Occupation | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.05 |

| Other Occupation | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.15 |

| Income | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Mother’s Income | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 |

| Black | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Latino | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.07 |

| Other Race | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.15 |

| U.S. Native | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Child Age | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Child is Male | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.04 |

| Length of Maternity Leave | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Positive Father Attitudes | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Engaged Father Attitudes | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.04 |

| Traditional Gender Attitudes | 0.08 | 0.04 † | 0.08 | 0.04 * | 0.08 | 0.04 † | 0.08 | 0.04 † |

| Prenatal Involvement | −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.09 |

| W1 Relationship Conflict | 0.63 | 0.06 *** | 0.62 | 0.06 *** | 0.62 | 0.06*** | 0.62 | 0.06*** |

| Leave-Taking × Religious Participation | −0.08 | 0.04 * | ||||||

| Length of Leave × Religious Participation | −0.04 | 0.02 † | ||||||

| R2 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | ||||

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petts, R.J. Paternity Leave, Father Involvement, and Parental Conflict: The Moderating Role of Religious Participation. Religions 2018, 9, 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9100289

Petts RJ. Paternity Leave, Father Involvement, and Parental Conflict: The Moderating Role of Religious Participation. Religions. 2018; 9(10):289. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9100289

Chicago/Turabian StylePetts, Richard J. 2018. "Paternity Leave, Father Involvement, and Parental Conflict: The Moderating Role of Religious Participation" Religions 9, no. 10: 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9100289

APA StylePetts, R. J. (2018). Paternity Leave, Father Involvement, and Parental Conflict: The Moderating Role of Religious Participation. Religions, 9(10), 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9100289