Do Religious Struggles Mediate the Association between Day-to-Day Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

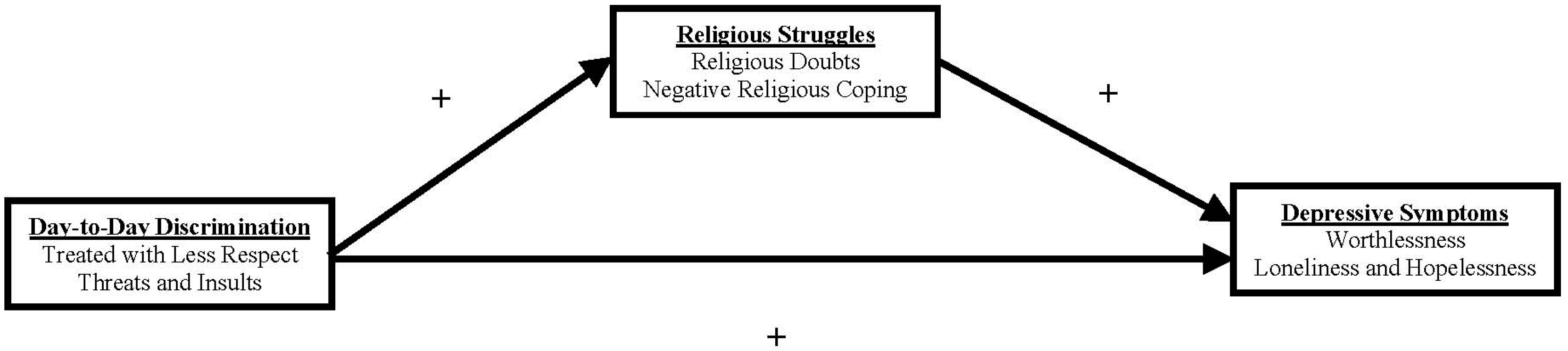

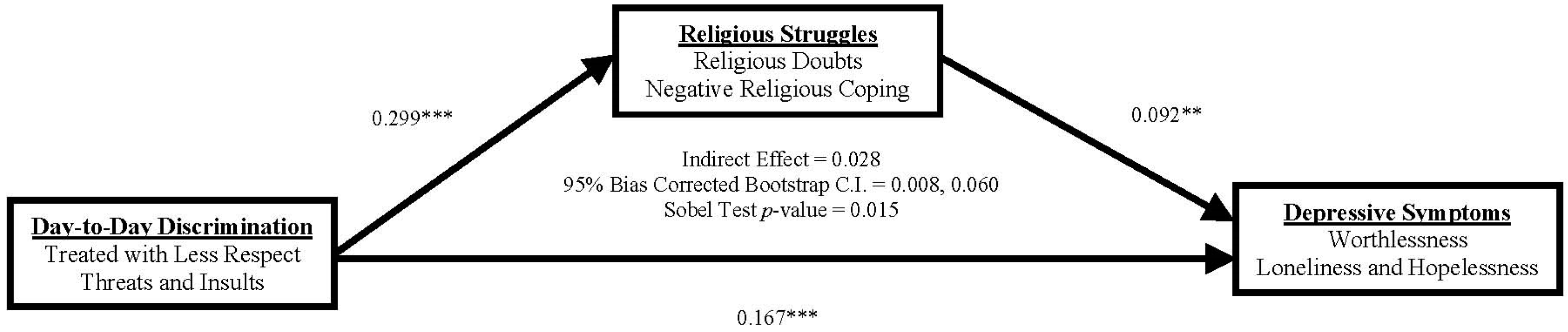

3.2. Multivariate Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ai, Amy Lee, Kenneth Pargament, Ziad Kronfol, Terrence N. Tice, and Hoa Appel. 2010. Pathways to Postoperative Hostility in Cardiac Patients Mediation of Coping, Spiritual Struggle and Interleukin-6. Journal of Health Psychology 15: 186–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, Rebecca S., Laura Lee Phillips, Lucinda Lee Roff, Ronald Cavanaugh, and Laura Day. 2008. Religiousness/spirituality and mental health among older male inmates. The Gerontologist 48: 692–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, Alvin N., and Linda P. Juang. 2010. Filipino Americans and racism: A multiple mediation model of coping. Journal of Counseling Psychology 57: 167–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ano, Gene G., and Erin B. Vasconcelles. 2005. Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology 61: 461–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardelt, Monika, and Cynthia S. Koenig. 2006. The role of religion for hospice patients and relatively healthy older adults. Research on Aging 28: 184–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borders, Ashley, and Christopher T. H. Liang. 2011. Rumination partially mediates the associations between perceived ethnic discrimination, emotional distress, and aggression. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 17: 125–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, Matt, Christopher G. Ellison, and Kevin J. Flannelly. 2008. Prayer, God imagery, and symptoms of psychopathology. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47: 644–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, Matt, Christopher G. Ellison, and Jack P. Marcum. 2010. Attachment to God, images of God, and psychological distress in a nationwide sample of Presbyterians. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 20: 130–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, Tony N., David R. Williams, James S. Jackson, Harold W. Neighbors, Myriam Torres, Sherrill L. Sellers, and Kendrick T. Brown. 2000. “Being black and feeling blue”: The mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Race and Society 2: 117–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Robyn Lewis, and R. Jay Turner. 2012. Physical limitation and anger: Stress exposure and assessing the role of psychosocial resources. Society and Mental Health 2: 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, Clare, Rory C. O’connor, Christine Howe, and David Warden. 2004. Perceived discrimination and psychological distress: The role of personal and ethnic self-esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology 51: 329–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Rodney, Norman B. Anderson, Vernessa R. Clark, and David R. Williams. 1999. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist 54: 805–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derogatis, Leonard. 2000. Brief Symptom Inventory 18, Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. Minneapolis: National Computer System. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, Michele, and Paul Wink. 2007. In the Course of a Lifetime: Tracing Religious Belief, Practice and Change. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, Christopher G. 1991. Religious involvement and subjective well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 32: 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, Christopher G., Amy M. Burdette, and Terrence D. Hill. 2009. Blessed assurance: Religion, anxiety, and tranquility among US adults. Social Science Research 38: 656–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, Christopher G., and Jinwoo Lee. 2010. Spiritual struggles and psychological distress: Is there a dark side of religion? Social Indicators Research 98: 501–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G., Lori A. Roalson, Janelle M. Guillory, Kevin J. Flannelly, and John P. Marcum. 2010. Religious resources, spiritual struggles, and mental health in a nationwide sample of PCUSA clergy. Pastoral Psychology 59: 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G., Qijuan Fang, Kevin J. Flannelly, and Rebecca A. Steckler. 2013. Spiritual struggles and mental health: Exploring the moderating effects of religious identity. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 23: 214–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G., Matt Bradshaw, Kevin J. Flannelly, and Kathleen C. Galek. 2014. Prayer, attachment to God, and symptoms of anxiety-related disorders among US adults. Sociology of Religion 75: 208–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, Julie Juola, Ann Marie Yali, and Marci Lobel. 1999. When God disappoints: Difficulty forgiving God and its role in negative emotion. Journal of Health Psychology 4: 365–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exline, Julie Juola, Ann Marie Yali, and William C. Sanderson. 2000. Guilt, discord, and alienation: The role of religious strain in depression and suicidality. Journal of Clinical Psychology 56: 1481–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, Julie Juola. 2002. Stumbling blocks on the religious road: Fractured relationships, nagging vices, and the inner struggle to believe. Psychological Inquiry 13: 182–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, Julie Juola, and Alyce Martin. 2005. Anger toward God: A new frontier in forgiveness research. In Handbook of Forgiveness Research. Edited by Everett L. Worthington Jr. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Exline, Julie Juola, and Eric Rose. 2005. Religious and spiritual struggles. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 315–30. [Google Scholar]

- Exline, Julie J., Crystal L. Park, Joshua M. Smyth, and Michael P. Carey. 2011. Anger toward God: Social-cognitive predictors, prevalence, and links with adjustment to bereavement and cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100: 129–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exline, Julie Juola, and Eric Rose. 2013. Religious and spiritual struggles. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 380–98. [Google Scholar]

- Exline, Julie J., Kenneth I. Pargament, Joshua B. Grubbs, and Ann Marie Yali. 2014. The Religious and Spiritual Struggles Scale: Development and initial validation. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 6: 208–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, Julie J., Steven J. Krause, and Karen A. Broer. 2016. Spiritual Struggle among Patients Seeking Treatment for Chronic Headaches: Anger and Protest Behaviors toward God. Journal of Religion and Health 55: 1729–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinstein, Brian A., Marvin R. Goldfried, and Joanne Davila. 2012. The relationship between experiences of discrimination and mental health among lesbians and gay men: An examination of internalized homonegativity and rejection sensitivity as potential mechanisms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 80: 917–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenelon, Andrew, and Sabrina Danielsen. 2016. Leaving my religion: Understanding the relationship between religious disaffiliation, health, and well-being. Social Science Research 57: 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, Ann R., and Kenna Bolton Holz. 2007. Perceived discrimination and women’s psychological distress: The roles of collective and personal self-esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology 54: 154–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitchett, George, Patricia E. Murphy, Jo Kim, James L. Gibbons, Jacqueline R. Cameron, and Judy A. Davis. 2004. Religious struggle: Prevalence, correlates and mental health risks in diabetic, congestive heart failure, and oncology patients. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 34: 179–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froese, Paul, and Christopher Bader. 2010. America’s Four Gods: What We Say about God and What that Says about Us. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galek, Kathleen, Neal Krause, Christopher G. Ellison, Taryn Kudler, and Kevin J. Flannelly. 2007. Religious doubt and mental health across the lifespan. Journal of Adult Development 14: 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall, Terry Lynn, Elizabeth Kristjansson, Claire Charbonneau, and Peggy Florack. 2009. A longitudinal study on the role of spirituality in response to the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 32: 174–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayman, Mathew D., and Juan Barragan. 2013. Multiple perceived reasons for major discrimination and depression. Society and Mental Health 3: 203–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, Gilbert C., Andrew Ryan, David J. Laflamme, and Jeanie Holt. 2006. Self-reported discrimination and mental health status among African descendants, Mexican Americans, and other Latinos in the New Hampshire REACH 2010 Initiative: The added dimension of immigration. American Journal of Public Health 96: 1821–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gee, Gilbert C., Michael Spencer, Juan Chen, Tiffany Yip, and David T. Takeuchi. 2007. The association between self-reported racial discrimination and 12-month DSM-IV mental disorders among Asian Americans nationwide. Social Science & Medicine 64: 1984–96. [Google Scholar]

- Grubbs, Joshua B., and Julie J. Exline. 2014. Why Did God Make Me This Way? Anger at God in the Context of Personal Transgressions. Journal of Psychology & Theology 42: 315–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Andrew. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Processes Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Terrence D., and Ryon Cobb. 2011. Religious involvement and religious struggles. In Toward a Sociological Theory of Religion and Health. Edited by Anthony J. Blasi. Leiden: Brill, pp. 239–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hunsberger, Bruce, Barbara McKenzie, Michael Pratt, and S. Mark Pancer. 1993. Religious doubt: A social psychological analysis. Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion 5: 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hunsberger, Bruce, Michael Pratt, and S. Mark Pancer. 2002. A longitudinal study of religious doubts in high school and beyond: Relationships, stability, and searching for answers. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 255–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ida, Aya Kimura, and C. André Christie-Mizell. 2012. Racial group identity, psychosocial resources, and depressive symptoms: Exploring ethnic heterogeneity among black Americans. Sociological Focus 45: 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idler, Ellen L., Marc A. Musick, Christopher G. Ellison, Linda K. George, Neal Krause, Marcia G. Ory, Kenneth I. Pargament, Lynda H. Powell, Lynn G. Underwood, and David R. Williams. 2003. Measuring multiple dimensions of religion and spirituality for health research: Conceptual background and findings from the 1998 General Social Survey. Research on Aging 25: 327–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, James S., Tony N. Brown, David R. Williams, Myriam Torres, Sherrill L. Sellers, and Kendrick Brown. 1995. Racism and the physical and mental health status of African Americans: A thirteen year national panel study. Ethnicity & Disease 6: 132–47. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, Verna M., Karen D. Lincoln, Robert Joseph Taylor, and James S. Jackson. 2010. Discriminatory experiences and depressive symptoms among African American women: Do skin tone and mastery matter? Sex Roles 62: 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, Ronald C., Kristin D. Mickelson, and David R. Williams. 1999. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 40: 208–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkpatrick, Lee A. 1992. An attachment-theory approach psychology of religion. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 2: 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal, Berit Ingersoll-Dayton, Christopher G. Ellison, and Keith M. Wulff. 1999. Aging, religious doubt, and psychological well-being. The Gerontologist 39: 525–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, Neal, and Keith M. Wulff. 2004. Religious doubt and health: Exploring the potential dark side of religion. Sociology of Religion 65: 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal. 2006. Religious doubt and psychological well-being: A longitudinal investigation. Review of Religious Research 47: 287–302. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, Neal, and Christopher G. Ellison. 2009. The doubting process: A longitudinal study of the precipitants and consequences of religious doubt in older adults. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48: 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, Neal, and R. David Hayward. 2012. Humility, lifetime trauma, and change in religious doubt among older adults. Journal of Religion and Health 51: 1002–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, Harold G., Kenneth I. Pargament, and Julie Nielsen. 1998. Religious coping and health status in medically ill hospitalized older adults. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 186: 513–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Hedwig, and Kristin Turney. 2012. Investigating the relationship between perceived discrimination, social status, and mental health. Society and Mental Health 2: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magyar-Russell, Gina, and Kenneth Pargament. 2006. The darker side of religion: Risk factors for poorer health and well-being. In Where God and Man Meet: How the Brain and Evolutionary Studies Alter Our Understanding of Religion. Edited by Patrick McNamera. Westport: Praeger Publishers, pp. 91–117. [Google Scholar]

- Mannheimer, Andrew H., and Terrence D. Hill. 2015. Deviating from religious norms and the mental health of conservative Protestants. Journal of Religion and Health 54: 1826–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConnell, Kelly M., Kenneth I. Pargament, Christopher G. Ellison, and Kevin J. Flannelly. 2006. Examining the links between spiritual struggles and symptoms of psychopathology in a national sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology 62: 1469–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, Byron, Sunshine M. Rote, and Verna M. Keith. 2013. Coping with racial discrimination: Assessing the vulnerability of African Americans and the mediated moderation of psychosocial resources. Society and Mental Health 3: 133–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, Bonnie, and Nadia Talal Hasan. 2004. Arab American persons’ reported experiences of discrimination and mental health: The mediating role of personal control. Journal of Counseling Psychology 51: 418–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossakowski, Krysia N. 2003. Coping with perceived discrimination: Does ethnic identity protect mental health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44: 318–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, Fanhao, and Daniel V. A. Olson. 2016. Demonic influence: The negative mental health effects of belief in demons. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 55: 498–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, Samuel, and Violet Kaspar. 2003. Perceived discrimination and depression: Moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. American Journal of Public Health 93: 232–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradies, Yin, Jehonathan Ben, Nida Denson, Amanuel Elias, Naomi Priest, Alex Pieterse, Arpana Gupta, Margaret Kelaher, and Gilbert Gee. 2015. Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 10: e0138511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Bruce W. Smith, Harold G. Koenig, and Lisa Perez. 1998. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 37: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Harold G. Koenig, Nalini Tarakeshwar, and June Hahn. 2004. Religious coping methods as predictors of psychological, physical and spiritual outcomes among medically ill elderly patients: A two-year longitudinal study. Journal of Health Psychology 9: 713–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Nichole A. Murray-Swank, Gina M. Magyar, and Gene G. Ano. 2005. Spiritual struggle: A phenomenon of interest to psychology and religion. In Judeo-Christian Perspectives on Psychology: Human Nature, Motivation, and Change. Edited by William R. Miller and Harold D. Delaney. Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 245–68. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Crystal. 2005. Religion and meaning. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by R. F. Paloutzian and C. L. Park. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 295–314. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe, Elizabeth A., and Laura Smart Richman. 2009. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin 135: 531–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoe, Anita E., Terrence D. Hill, Krysia N. Mossakowski, and Robert J. Johnson. 2016. Religious involvement and perceptions of control: Evidence from the Miami-Dade Health Survey. Journal of Religion and Health 55: 862–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, Amy J., Clarence C. Gravlee, David R. Williams, Barbara A. Israel, Graciela Mentz, and Zachary Rowe. 2006. Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among African American women in Detroit: Results from a longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Public Health 96: 1265–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Timothy B., Michael E. McCullough, and Justin Poll. 2003. Religiousness and depression: Evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin 129: 614–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stauner, Nick, Julie J. Exline, Joshua B. Grubbs, Kenneth I. Pargament, David F. Bradley, and Alex Uzdavines. 2016. Bifactor models of religious and spiritual struggles: Distinct from religiousness and distress. Religions 7: article 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, Patrick R., and Matthew Bowden. 2006. Sleep disturbance mediates the relationship between perceived racism and depressive symptoms. Ethnicity & Disease 5: 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sternthal, Michelle J., David R. Williams, Marc A. Musick, and Anna C. Buck. 2010. Depression, Anxiety, and Religious Life A Search for Mediators. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 51: 343–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, John, and R. Jay Turner. 2002. Perceived discrimination, social stress, and depression in the transition to adulthood: Racial contrasts. Social Psychology Quarterly 65: 213–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenholm, Penelope. 1998. Negative religious conflict as a predictor of panic disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology 54: 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uecker, Jeremy E., Christopher G. Ellison, Kevin J. Flannelly, and Amy M. Burdette. 2016. Belief in Human Sinfulness, Belief in Experiencing Divine Forgiveness, and Psychiatric Symptoms. Review of Religious Research 58: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghela, Preeti, and Angelina R. Sutin. 2016. Discrimination and sleep quality among older US adults: The mediating role of psychological distress. Sleep Health 2: 100–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versey, H. Shellae, and Nicola Curtin. 2016. The differential impact of discrimination on health among Black and White women. Social Science Research 57: 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, Ian R., Patrick Royston, and Angela M. Wood. 2011. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Statistics in Medicine 30: 377–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, David R., Yan Yu, James S. Jackson, and Norman B. Anderson. 1997. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology 2: 335–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, David R., Harold W. Neighbors, and James S. Jackson. 2003. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health 93: 200–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilt, Joshua A., Julie J. Exline, Joshua B. Grubbs, Crystal L. Park, and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2016a. God’s role in suffering: Theodicies, divine struggle, and mental health. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 8: 352–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilt, Joshua A., Joshua B. Grubbs, Julie J. Exline, and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2016b. Personality, religious and spiritual struggles, and well-being. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 8: 341–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilt, Joshua A., Joshua B. Grubbs, Kenneth I. Pargament, and Julie J. Exline. 2017. Religious and spiritual struggles, past and present: Relations to the big five and well-being. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 27: 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortmann, Jennifer H., Crystal L. Park, and Donald Edmondson. 2011. Trauma and PTSD symptoms: Does spiritual struggle mediate the link? Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 3: 442–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Tse-Chuan, and Kiwoong Park. 2015. To what extent do sleep quality and duration mediate the effect of perceived discrimination on health? Evidence from Philadelphia. Journal of Urban Health 92: 1024–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Depressive Symptoms | Day-to-Day Discrimination | Religious Struggles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Distressed or bothered by feeling blue | 0.84 | ||

| 2. Distressed or bothered by feelings of worthlessness | 0.77 | ||

| 3. Distressed or bothered by feeling no interest in things | 0.76 | ||

| 4. Distressed or bothered by feeling lonely | 0.72 | ||

| 5. Distressed or bothered by feeling hopeless about future | 0.67 | ||

| 6. You are called names or insulted | 0.76 | ||

| 7. People act as if they think you are not smart | 0.71 | ||

| 8. You are treated with less respect than other people | 0.69 | ||

| 9. People act as if they’re better than you are | 0.69 | ||

| 10. You are threatened or harassed | 0.68 | ||

| 11. People act as if they think you are dishonest | 0.64 | ||

| 12. People act as if they are afraid of you | 0.53 | ||

| 13. You feel that God is punishing you for your sins | 0.79 | ||

| 14. You wonder whether God has abandoned you | 0.75 | ||

| 15. You have doubts about your religious or spiritual beliefs | 0.60 | ||

| Eigenvalues | 2.86 | 3.18 | 1.55 |

| Range | Mean | Standard Dev. | Alpha Reliability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day-to-Day Discrimination | 0–4 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.79 |

| Depressive Symptoms | 0–4 | 0.42 | 0.68 | 0.80 |

| Religious Struggles | 0–4 | 0.54 | 0.69 | 0.54 |

| Age | 18–95 | 56.65 | 16.65 | |

| Female | 0–1 | 0.70 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0–1 | 0.31 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0–1 | 0.14 | ||

| Hispanic | 0–1 | 0.41 | ||

| Other Race/Ethnicity | 0–1 | 0.14 | ||

| US-Born | 0–1 | 0.47 | ||

| Spanish Interview | 0–1 | 0.31 | ||

| Education | 0–3 | 1.27 | 1.14 | |

| Employed | 0–1 | 0.45 | ||

| Household Income | 0–9 | 4.83 | 2.69 | |

| Financial Strain | 0–4 | 1.28 | 1.01 | 0.61 |

| Married | 0–1 | 0.62 | ||

| Religious Involvement | −2.04–1.24 | −0.01 | 0.77 | 0.85 |

| Religious Struggles | Depressive Symptoms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day-to-Day Discrimination | 0.299 | *** | 0.194 | *** | 0.167 | *** |

| Religious Struggles | 0.092 | ** | ||||

| Age | −0.004 | −0.001 | −0.000 | |||

| Female | 0.083 | 0.071 | 0.064 | |||

| Hispanic | 0.025 | −0.021 | −0.024 | |||

| Non−Hispanic Black | −0.065 | −0.098 | −0.092 | |||

| Other Race/Ethnicity | 0.118 | −0.002 | −0.013 | |||

| US−Born | −0.225 | * | 0.012 | 0.033 | ||

| Spanish Interview | −0.216 | 0.156 | * | 0.176 | ** | |

| Education | −0.020 | 0.002 | 0.004 | |||

| Employed | −0.080 | −0.132 | * | −0.124 | * | |

| Household Income | 0.003 | −0.003 | −0.003 | |||

| Financial Strain | 0.035 | 0.103 | *** | 0.099 | *** | |

| Married | 0.184 | ** | −0.117 | * | −0.134 | ** |

| Religious Involvement | −0.061 | −0.048 | −0.043 | |||

| R−squared | 0.133 | 0.171 | 0.187 | |||

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hill, T.D.; Christie-Mizell, C.A.; Vaghela, P.; Mossakowski, K.N.; Johnson, R.J. Do Religious Struggles Mediate the Association between Day-to-Day Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms? Religions 2017, 8, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8080134

Hill TD, Christie-Mizell CA, Vaghela P, Mossakowski KN, Johnson RJ. Do Religious Struggles Mediate the Association between Day-to-Day Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms? Religions. 2017; 8(8):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8080134

Chicago/Turabian StyleHill, Terrence D., C. André Christie-Mizell, Preeti Vaghela, Krysia N. Mossakowski, and Robert J. Johnson. 2017. "Do Religious Struggles Mediate the Association between Day-to-Day Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms?" Religions 8, no. 8: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8080134

APA StyleHill, T. D., Christie-Mizell, C. A., Vaghela, P., Mossakowski, K. N., & Johnson, R. J. (2017). Do Religious Struggles Mediate the Association between Day-to-Day Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms? Religions, 8(8), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8080134