Linguistic Decipherment of the Lettering on the (Original) Carving of the Virgin of Candelaria from Tenerife (Canary Islands)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Previous Proposed Solutions

- The first known solution belongs to Gonzalo Argote de Molina (1548–1596) and were gathered by Juan de Abreu Galindo, O.F.M. (ca. 1535–?) in History of the conquest of the seven Canary Islands (1676) (Historia de la conquista de las siete Islas de Canaria), a sort of Latin acronyms of devotional fervour which are applied to four incomplete fragments (Abreu Galindo [1676] 1977).Thus, for example, was proposed as the solution to the text on the neckline, TIEPFSEPMERI: Illustrata Es Patri Filio Spíritu-santo Et Pia Mater Eiusdem Redemptoris Iesu. Or for the lettering on the girdle, NARMPRLMOTARE: Nostrum Altíssimum Regem Maria Peperit Reddidit Libertatem Maria Omnibus Tortis A Rege Erebia. We will leave it here, as we consider this is a sufficiently good illustration of the way to solve the textual group, and which has been broadly discussed already (Vera 2016, pp. 42–46, 73–74).

- The proposal by Athanasius Kircher, S.I. (1602–1680), gathered by Jesús Alonso de Andrade, S.I. (1590–1672) in Universal Patronage of the Holy Virgin Mary, Mother of God and our Lady (1664) (Patrocinio universal de la santissima Virgen Maria, Madre de Dios, y Señora Nuestra), and Juan Núñez de la Peña (1641–1721) in Conquest and antiquities of the island of Gran Canaria and its description, along with many warnings about its privileges, conquerors, settlers and other special features in the highly powerful island of Tenerife, addressed to the miraculous image of Our Lady of Candelaria (1676) (Conquista y antigüedades de la isla de la Gran Canaria y su descripción, con muchas advertencias de sus privilegios, conquistadores, pobladores y otras particularidades en la muy poderosa isla de Tenerife, dirigido a la milagrosa imagen de Nuestra Señora de Candelaria), assuming an Arabian linguistic origin for pious purposes only, without any scientific contribution whatsoever (de Andrade 1664; de Béthencourt Massieu 2004; Núñez de la Peña 1676; Vera 2016, pp. 51–55, 74–75).Thus, we give the examples of the neckline and the girdle again: TIEPESEPMERI: Insignes Matris/Tipus Matris. In the case of the girdle, with the letters NARMPRLOTARE: Pro nobis ora, vel advocatio/Pro novis ora, vel advocate.

- Other proposals are the Latin acronyms and pseudo-acronyms by Bartolomé García Ximénez (1622–1690), who never intended to solve the conundrum of the lettering but to offer a compilation of pious and devotional lists to the people that, astonished, went to visit the Marian carving (Moure 1991, pp. 49–54; Vera 2016, pp. 55, 60, 75–76).Again, we compile those corresponding to the neckline and to the girdle of the statue, in the form of example of how he proceeded: ETIEPESEPMERI: Eccleciae Triumfantis In Excelsis {Preposita/Praeposita} Electa Sanctorum Et Patrona Militantis Ecclesiae Romanae {Infalibilis/Indefectibilis}. NARMPRLMOTARE: Non Ambio Regnorum Magna Palatia Requiro Litora Maris Oceani {Thenerifensis/Thenerifensia} Ad Rusticos Edocendos.

- John Campbell (1840–1904) made a striking contribution, in Archaic-Basque language and with Etruscan and Iberian influences. Utterly surprising in its conclusion, we give the plain example of the fragments on the neckline and the girdle: (Campbell 1901; Vera 2016, pp. 77–78):TIEPFSEPMERI on the neckline, conveying the words: ko i en tu po no en tu me ne ra au: Koi entu pono entu Menera au (Desire hear grief hear Menera this): Let this (goddess) Menera hear the prayer, hear the sorrow (Campbell 1901, p. 60; Vera 2016, p. 77).Or, on the girdle: (M/N) ARMPRLMOTARE, mi ra er mi to ri se me ma gu re er en: mira erimi etorri seme etna gure erren (spectacle cause place come son give our compassion): Coming to cause to set up a spectacle, to give the son our compassion (Campbell 1901, p. 61; Vera 2016, pp. 77–78).

- An additional proposed solution was given by Antonio María Manrique (1837–1907), who assumes it is in the Semitic Language, by gathering biblical passages or devotional Christian ones, which applies to two fragments on the garment. To be precise, the lettering on the neckline supposedly must convey the name of the represented figure, and so we might expect to find something like Mary, full of grace, whereas, on the girdle, we could expect it to mean One God and Father of all, without further contributions or base for his hypotheses (Manrique 1898; Vera 2016, p. 79).

- Another suggestion, including a syncretic combination of Spanish, Portuguese and Italian, is the one proposed by Alonso Ascanio y Negrín (1855–1936), who provides the meaning ME SOBRA O GAJE for the neckline, EVIIOJ DE NOVIA for the girdle, or even the author and date LA FIXE SINESIVJ ZEA MCCXLIX for the back of the cape (Negrín 1899; Vera 2016, p. 80).

- Yet another proposal comes from Fidel Fita Colomé, S.I. (1845–1918) (Moure 1991, pp. 65–67; Vera 2016, pp. 80–81), a transposition of the Latin language highly modified into a biblical sense, even though he worked on one fragment of the inscriptions only, the one on the neckline to be exact, ETIEPESEPMERI, which offers the redistribution of the text Sepi et eripe me (protect and rescue me), referring to the invoking of the litany Turris ebúrnea (ivory tower) according to the Song of Songs 8, 4 (Bible 1611, p. 3L6r), or rather, Cant 4, 4 (Bible 1611, p. 3L5r) or Isaiah 5, 2, which reads Et sepivit eam, [...] et aedificavit turrim (and gathered out the stones thereof (the vineyard) [...] and built a tower) (Bible 1611, p. 3M2v; Moure 1991, pp. 65–67; Tvveedale 2005, p. 835).

- Lastly, the multi-pseudo-acronyms from Latin and Spanish carrying religious meaning about three fragments, by José Hernández Morán (1922–) which, by way of example, we provide for the lettering on the neckline only, where two interpretations are possible: on the one hand, the sub-division TI-E-PE-SEP-MERI, resulting in the phrase Forever you are Mary (Tú eres por siempre María), from Kircher’s variation, or else, the more unnatural form TI-ERES-EP-MERI, that is, You are a mother’s mirror (Tú eres espejo de madre), which is intended to be shown in the same semantic line as Tipus Matris (Image of the Mother) by the Jesuit (Morán 1957; Vera 2016, p. 81).

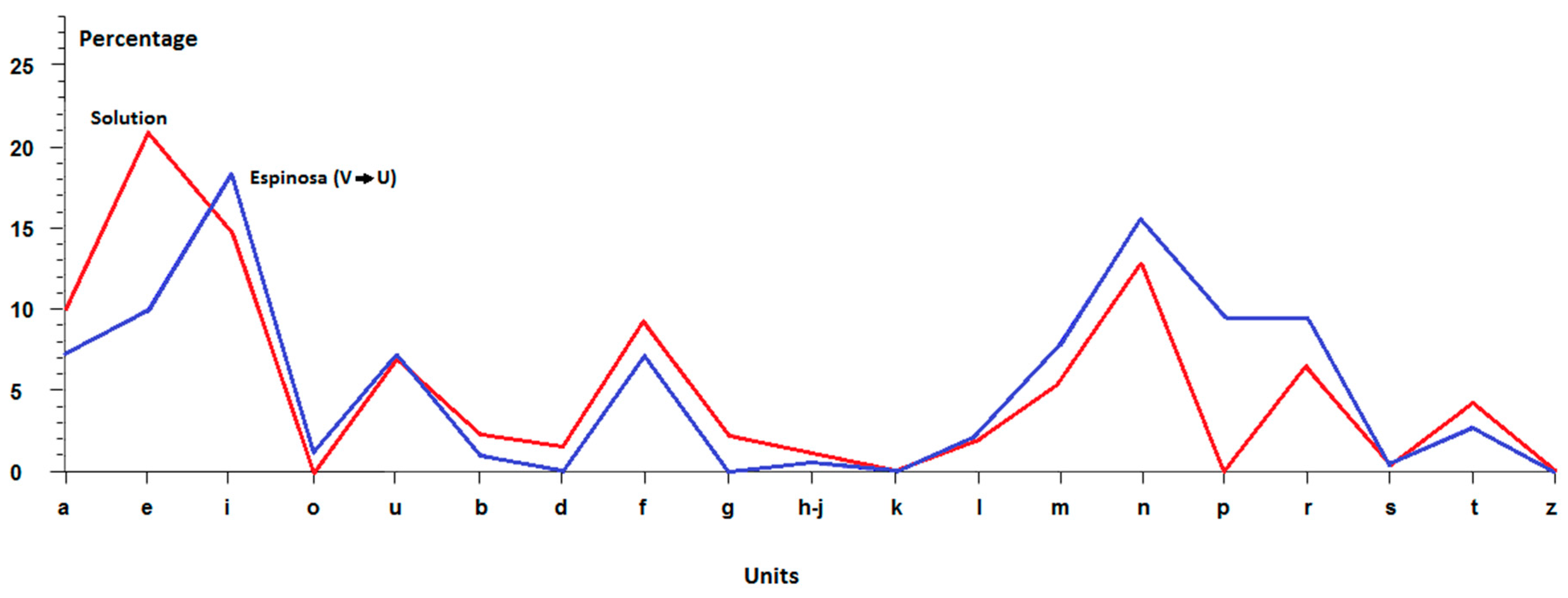

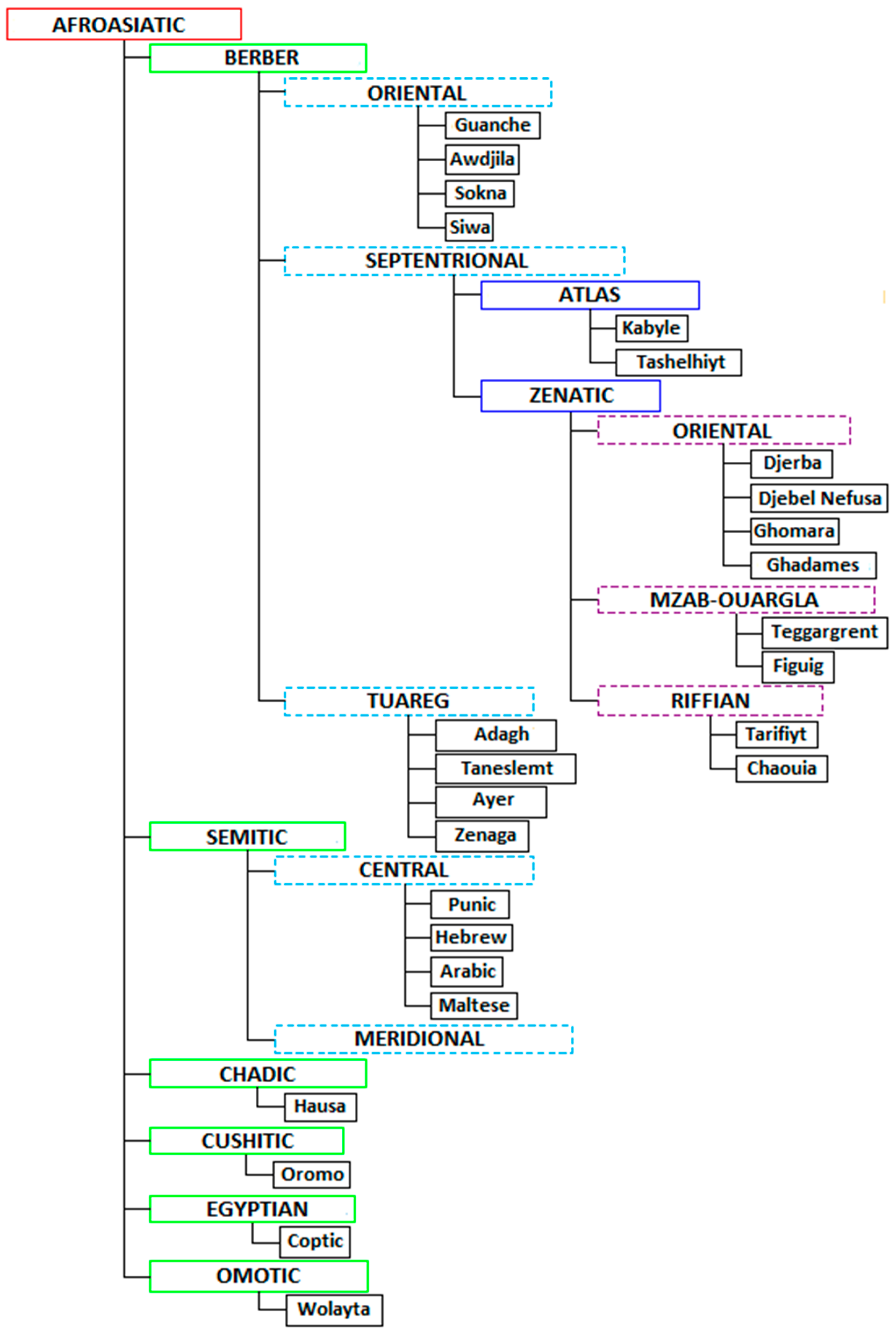

3. The Insular-Amazigh Proposal

4. Our Proposal for a Solution

4.1. Philological Explanation of the Different Fragments of the Inscription

4.1.1. TIEPFSEPMERI

4.1.2. NARMPRLMOTARE

4.1.3. LPVRINENIPEPNEIFANT

4.1.4. OLM

4.1.5. INRANFR

4.1.6. IAEBNPFM

4.1.7. RFVEN

4.1.8. NVINAPIMLIFINVIPI

4.1.9. NIPIAN

4.1.10. FVPMIRNA

4.1.11. ENVPMTI

4.1.12. EPNMPIR

4.1.13. VRVIVINRN

4.1.14. APVIMFRI

4.1.15. PIVNIAN

4.1.16. NTRHN

4.1.17. EAFM

4.1.18. IRENINI

4.1.19. FMEAREI

4.1.20. NBIMEI

4.1.21. ANNEIPERFMIVIFVF

4.2. Final Clarifications and Remarks

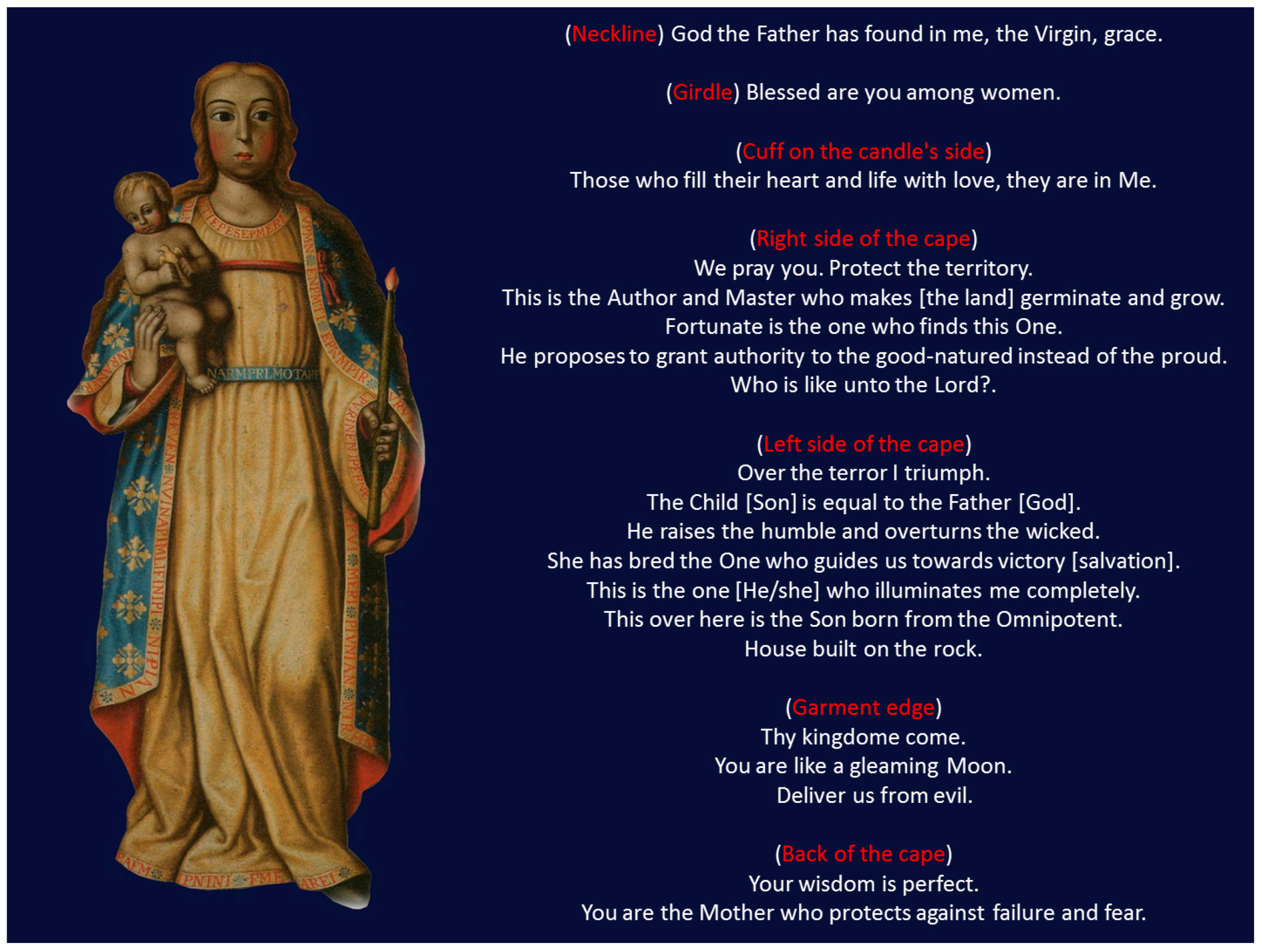

- (Neckline) TIEPFSEPMERI.

- God the Father has found in me, the Virgin, grace.

- (Girdle) NARMPRLMOTARE.

- Blessed are you among women.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Psalm | The Book of Psalms |

| Cant | The Song of Songs |

| Dn | The Book of Daniel |

| Mt | The Gospel According to Matthew |

| Luk | The Gospel According to Luke |

| Jn | The Gospel According to John |

| Rm | The Epistle of Paul to the Romans |

| Col | The Epistle of Paul to the Colossians |

| Rev | The Book of Revelation |

References

- Abreu Galindo, Juan de. 1977. Historia de la Conquista de las Siete Islas de Canaria. Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Goya Ediciones, pp. 308–9. First published 1676. [Google Scholar]

- Basset, René. 1890. Le dialecte de Syouah. Paris: L’École des Lettres d’Alger, Ernest Leroux. [Google Scholar]

- Basset, René. 1893. Étude sur la Zenatia du Mzab de Ouargla et de L’Oued-Rir. Paris: L’École des Lettres d’Alger, Ernest Leroux. [Google Scholar]

- Bible, King James. 1611. The Holy Bible, Containing the Old Testament, and the New: Newly Translated out of the Original Tongues: & with the Former Translations Diligently Compared and Revised, by His Majesties Special Commandment. London: Robert Barker. [Google Scholar]

- Blastic, Michael W. 2007. Prayer in the writings of Francis of Assisi and the early brothers. In Franciscans at Prayer. Edited by Johnson Timothy J. Leiden: Brill, pp. 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, Juan Carlos Moreno. 2003. El Universo de las Lenguas: Clasificación, Denominación, Situación, Topología, Historia y Bibliografía de las Lenguas. Madrid: Castalia. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, John. 1901. Critical examination of Spanish documents relative to the Canary Islands, submitted to the writer by Senor Don Juan Bethencourt Alfonso, of Tenerife. Transactions of the Canadian Institute 7: 29. [Google Scholar]

- Cervera, Jesús Castellano. 2001. Santa María en Oriente y Occidente. Barcelona: Centro de Pastoral Litúrgica. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, John. 1852. The Psalter of the Blessed Virgin Written by st. Bonaventure. London: The British Reformation Society. [Google Scholar]

- Dallet, Jean-Marie. 1982. Dictionnaire Kabyle-Français: Parler des At Mangellat, Algérie. 2 vols, Paris: Selaf. [Google Scholar]

- de Andrade, Jesús Alonso. 1664. Patrocinio Universal de la Santissima Virgen Maria, Madre de Dios, y Señora Nuestra. Madrid: Joseph Fernandez de Buendia, pp. 454–57. [Google Scholar]

- de Béthencourt Massieu, Antonio. 2004. Idea de la conquista de estas islas (1679): Núñez de la Peña en la historiografía canaria. Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos 50: 886. [Google Scholar]

- de Calasanti-Motylinski, Gustave Adolphe. 1898. Le Djebel Nefousa. Transcription, Traduction Française et Notes Avec Une Étude Grammaticale. Paris: Ernest Leroux. [Google Scholar]

- de Espinosa, Alonso. 1980. Historia de Nuestra Señora de Candelaria. Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Goya Ediciones. First published 1594. [Google Scholar]

- de Foucauld, Charles. 1951–1952. Dictionnaire Touareg-Français: Dialecte de l'Ahaggar. 4 vols, Paris: Imprimerie Nationale de France. [Google Scholar]

- Delheure, Jean. 1984. Dictionnaire Mozabite-Français. Paris: Selaf. [Google Scholar]

- Delheure, Jean. 1987. Dictionnaire Ouargli-Français. Paris: Selaf. [Google Scholar]

- Esser, Kajetan. 1980. Devoción a María Santísima. Oñate: Aránzazu Franciscana, pp. 281–309. [Google Scholar]

- Evenou, Jean. 2007. Las Letanías: Antología, Letanías de los Santos, Letanías de Invocación al Señor, Letanías de Invocación a la Virgen. Barcelona: Centro de Pastoral Litúrgica, pp. 73–78, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Faidherbe, Louis Léon César. 1877. Le Zénaga des Tribus Sénégalaises. Paris: Ernest Leroux. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ignacio Reyes. 2010. La Madre del Cielo: Estudio de Filología Ínsuloamazighe. Islas Canarias: Fondo de Cultura Ínsuloamaziq. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ignacio Reyes. 2011. Diccionario Ínsuloamaziq. Islas Canarias: Fondo de Cultura Ínsuloamaziq. [Google Scholar]

- Graef, Hilda Charlotte. 1968. María: La Mariología y el Culto Mariano a Través de la Historia. Barcelona: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, Jeffrey. 2005. A Grammar of Tamashek (Tuareg of Mali). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, Jeffrey. 2006. Dictionnaire Touareg du Mali. Tamachek-Anglais-Français. Paris: Karthala. [Google Scholar]

- Hexter, Ralph, and David Townsend. 2012. The Oxford Handbook of Medieval Latin Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 378–79. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Timothy J. 2007. The Prothemes of Bonaventure’s sermones dominicales and minorite prayer. In Franciscans at Prayer. Edited by Johnson Timothy J. Leiden: Brill, pp. 109–12. [Google Scholar]

- King, Robert. 1840. The Psalter of the Blessed Virgin Mary illustrated. Dublin: Grant & Bolton, p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Kossmann, Maarten G. 1999. Essai sur la Phonologie du Proto-Berbère (Grammatical Analyses of African Languages). Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kossmann, Maarten G. 2013. The Arabic Influence on Northern Berber. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kossmann, Maarten G., and Harry J. Stroomer. 1997. Berber phonology. In Phonologies of Asia and Africa. Edited by Kaye Alan S. and Daniels Peter T. vol. 1, Warsaw: Eisenbrauns, pp. 461–75. [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq, Henri. 1913. Monvmenta Ecclesiae Litvrgica. Paris: F. Didot, vol. 2, pp. 225–27. [Google Scholar]

- Manrique, Antonio María. 1898. La Virgen de Candelaria. La Opinión de Tenerife 1920: 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, John Desmond. 2004. Mary's Maternal Mediation: Is it True to Say Mary Is Coredemptrix, Mediatrix of all Graces and Advocate? New Bedford: Academy of the Immaculate. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, Carlos Rodríguez. 2009. Catálogo. In Vestida de Sol: Iconografía y Memoria de Nuestra Señora de Candelaria. Edited by Carlos Rodríguez Morales. San Cristóbal de La Laguna: Caja General de Ahorros de Canarias, pp. 142–43. [Google Scholar]

- Morán, José Hernández. 1957. Sobre las letras de la primitiva imagen de la Virgen de Candelaria. Revista de Historia Canaria 117–118: 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Moure, José Rodríguez. 1991. Historia de Achmaye-Guayaxeras-Achoron-Achaman, Nuestra Señora de Candelaria. Candelaria: Cabildo Insular de Tenerife. [Google Scholar]

- Naït-Zerrad, Kamal. 1998–1999, 2002. Dictionnaire des Racines Berbères (Formes Attestées). 3 vols, Paris and Louvain: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Negrín, Alonso Ascanio y. 1899. Ntra. Sra. de Candelaria y lo que Dicen sus Letras. La Orotava: Adolfo Herreros. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez de la Peña, Juan. 1676. Conquista y Antigüedades de la Isla de la Gran Canaria y su Descripción, con Muchas Advertencias de sus Privilegios, Conquistadores, Pobladores y Otras Particularidades en la Muy Poderosa Isla de Tenerife, Dirigido a la Milagrosa Imagen de Nuestra Señora de Candelaria. Madrid: Imprenta Real Florián Anisson. [Google Scholar]

- Peltomaa, Leena Mari. 2001. The Image of the Virgin Mary in the Akathistos Hymn. Leiden: Brill, pp. 191–94. [Google Scholar]

- Prasse, Karl Gottfri. 1984. The origin of the vowels o and e in Twareg and Ghadamsi. In Current Progress in Afro-Asiatic Linguistics. Edited by Bynon James. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 317–25. [Google Scholar]

- Prasse, Karl Gottfri. 1990. New light on the origin of the Tuareg vowels e and o. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Hamito-Semitic Congress. Edited by Mukarovsky Hans G. Vienna: Afro-Pub, pp. 163–70. [Google Scholar]

- Prasse, Karl Gottfried, Ghoubeïd Alojaly, and Ghabdouane Moham. 2003. Dictionnaire Touareg-Français (Niger). Copenhague: Museum Tusculanum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, Hans, and Prasse Karl Gottfri. 2009. Dictionnaire Touareg. 2 vols, Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Robledo, Esteban Ibáñez. 1944. Diccionario Español-Rifeño. Madrid: Verdad y Vida. [Google Scholar]

- Robledo, Esteban Ibáñez. 1949. Diccionario Rifeño-Español (Etimológico). Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos. [Google Scholar]

- Saxonia, Conradi a. 1904. Speculum Beatae Mariae Virginis. Quaracchi: Collegii S. Bonaventurae, pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- SBI (Société Biblique Internationale). 1995. Awal n Tudert: Adlis n Leɛqed Ajdid Aked Ihellilen. [Word of Life, Holy Bible: New Testament with Psalms]. Paris: Association Chrétienne d`Expression Berbère. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, Martin. 1981. San Francisco y la Virgen María. Selecciones de Franciscanismo, 10–28. [Google Scholar]

- Taifi, Miloud. 1991. Dictionnaire Tamazight-Français (Parlers du Maroc Central). Paris: L’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Taine-Cheikh, Catherine. 2008. Dictionnaire Zénaga-Français: Le Berbère de Mauritanie Présenté par Racines Dans Une Perspective Comparative. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Takács, Gábor. 2005. Some Berber etymologies IV: Lexical roots with *f. Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia 10: 165–93. [Google Scholar]

- Tvveedale, Michaele. 2005. Biblia Sacra Juxta Vulgatam Clementinam. Londini: Conference of Bishops of England and Wales. [Google Scholar]

- van Putten, Marijn. 2014. A Grammar of Awjila Berber (Libya): Based on Umberto Paradisi's material. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Vera, Vicente Jara. 2016. Contexto, criptoanálisis y propuesta de solución de la inscripción de la talla (original) de la Virgen de Candelaria de Tenerife (Canarias, España). Ph.D. Telecommunications Engineering, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, España, January 27. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jara Vera, V.; Sánchez Ávila, C. Linguistic Decipherment of the Lettering on the (Original) Carving of the Virgin of Candelaria from Tenerife (Canary Islands). Religions 2017, 8, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8080135

Jara Vera V, Sánchez Ávila C. Linguistic Decipherment of the Lettering on the (Original) Carving of the Virgin of Candelaria from Tenerife (Canary Islands). Religions. 2017; 8(8):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8080135

Chicago/Turabian StyleJara Vera, Vicente, and Carmen Sánchez Ávila. 2017. "Linguistic Decipherment of the Lettering on the (Original) Carving of the Virgin of Candelaria from Tenerife (Canary Islands)" Religions 8, no. 8: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8080135

APA StyleJara Vera, V., & Sánchez Ávila, C. (2017). Linguistic Decipherment of the Lettering on the (Original) Carving of the Virgin of Candelaria from Tenerife (Canary Islands). Religions, 8(8), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8080135