Abstract

This paper examines select paintings by Holocaust survivor and painter Samuel Bak from his recent Just Is series. The essay explores ways Bak’s art bears witness to suffering. He creatively interrogates and reanimates the iconic figure of Lady Justice and the biblical principle of the lex talionis (“eye for an eye”) in order to fashion alternative icons fit for an age of atrocity and loss. Bak’s artwork gives visual expression to Theodor Adorno’s view of the precariousness of art after Auschwitz. It is art’s responsibility to attend to the burden of real suffering experiences (the burden of the empirical) and to think in contradictions, which renders art both adequate and inadequate in standing up against the injustice of other’s suffering. Through inventive juxtaposition of secular and sacred symbols, Bak displays the paradox of representation after the Holocaust and art’s precarious responsibility giving voice to suffering. Bak fashions visual spaces in which barbarity and beauty coincide and collide. He invites viewers into this space and into dialogue about justice’s standing and promises. Do Bak's remade icons of Just Is lament a permanent loss of justice and peace, or do they point tentatively to possibilities of life lived in a damaged world with an alternative Just Is? Bak’s artwork prompts such vexing questions for his viewers to contemplate and leaves them to decide what must be done.

Keywords:

Samuel Bak; Holocaust art; Lady Justice; lex talionis; eye for an eye; icon; justice; Theodor Adorno; atrocity; suffering 1. Introduction

In the artwork of Samuel Bak, Holocaust child survivor and painter, we encounter a creative effort to give structure to suffering and represent loss in an extraordinary series of paintings entitled Just Is. In images of striking beauty and barbarity, Bak bears witness to personal and communal suffering and injustice through representations of catastrophe that convey the paradox and precariousness of his art. In this collection of 59 paintings, Bak interrogates and animates iconic images of Lady Justice and the lex talionis, the biblical principle of retributive justice commonly expressed as “eye for an eye.” By incorporating and transforming these figures, Bak challenges secular and sacred concepts of justice and the narratives sustaining them that distance us from the material reality of human suffering. In so doing he challenges his viewers to consider how they are to respond to the suffering of others. Theodor Adorno’s call for art produced after Auschwitz to think in contradictions and to refuse abstractions of suffering contributes a critical perspective in reading Bak’s images that insists upon art’s special responsibility to respond to real-world injustices. In these challenging compositions and the questions he raises, we see the original way Bak’s artwork meets this moral responsibility, and how Bak’s suffering finds its voice through a reimagining of icons of Just Is fashioned for the important task of repairing a damaged world.

2. Adorno and Art’s Suffering Responsibility

“Is there any meaning in life when men exist who beat people until the bones break in their bodies?” (Adorno 1985, p. 312).1 This question, unsettling for the graphic violence it pictures, directs Theodor Adorno’s critique of art that detaches itself from the suffering reality of broken bones and even the right for persons to exist. For Adorno, German philosopher, gifted composer, and Jewish refugee, reflection on the relationship of suffering and art serves as a lens for diagnosing the failure of Enlightenment values and ideals to achieve human freedom and dignity expressed most appallingly in Auschwitz,2 emblematic of the Nazi-administered world of unspeakable suffering and violence.3 Critical of philosophical and theological narratives that attribute meaning to suffering, Adorno insists upon art’s role in keeping concrete suffering before our eyes as a way to counter the abstractions that distance one person from the material reality of another’s pain. Suffering remains “mute and inconsequential” when it is conceptualized, he warns (Adorno 1997, p. 18). Art that abstracts and aestheticizes broken bones commodifies and abases that suffering and sustains the culture responsible for it. Hence, art after Auschwitz must be “burdened by the weight of the empirical” (Adorno 1997, p. 19) and “to think in contradictions” (Adorno 1992, p. 145) if it is to respond truthfully and morally to cultural suffering and injustice.4

But how can art speak truthfully and ethically to suffering when, as Adorno famously declares, “to write lyric poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric” (Adorno 1985, p. 312)? This oft-quoted statement is heard by many as a call to silence poetry—and art more broadly—in the face of the extremity of the Holocaust world.5 However, when contextualized within his broader critique of the disenchanted modern world and the positive role negation plays in his dialectical analysis of culture, his accusing statement is to be taken not as a prohibition against representation of barbarity but rather as a paradoxical call for art to actively “think against itself” in the process of re-presenting the brutality.6 In response to the atrocities of the modern world, art after Auschwitz has no alternative but to grapple with the concrete realities of suffering and torture while refusing to give meaning to them. Adorno will later make the contradiction and moral imperative explicit: “to write lyric poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric…But it also remains true that literature must resist this verdict” (Adorno 1985, p. 313, my emphasis). Resisting this verdict means that the sufferings of broken bones and damaged lives demand remembering as a matter of justice, which is now art’s distinctive obligation: “The abundance of real suffering tolerates no forgetting,” he insists. “[I]t is now virtually in art alone that suffering can still find its own voice, consolation, without immediately being betrayed by it. The most important artists of the age have realized this” (Adorno 1985, p. 312).

After Auschwitz, art occupies a precarious place in history and culture that simultaneously prohibits and demands its continuing existence in response to the injustice of six million murdered (Nosthoff 2014), by any measure an unbearable empirical burden. These sufferings of broken bones and damaged lives demand remembering as a matter of justice, which is now art’s obligation: “The abundance of real suffering tolerates no forgetting,” he insists. “[I]t is now virtually in art alone that suffering can still find its own voice, consolation, without immediately being betrayed by it. The most important artists of the age have realized this” (Adorno 1985, p. 312).

Art’s conundrum in not forgetting suffering lies in the fact that, in the process of enabling suffering to find its voice and consolation, it inevitably renders the suffering of beaten and broken bodies into meaningful images.7 “The so-called artistic representation of the sheer physical pain of people beaten to the ground by rifle butts contains, however remotely, the power to elicit enjoyment out of it” (Adorno 1985, p. 313). Like grand narratives, aesthetic stylization can betray suffering by “mak[ing] an unthinkable fate appear to have had some meaning; …transfigured, something of its horror is removed” (p. 313). When the suffering of victims, and genocidal violence more broadly, becomes a theme in art and literature, Adorno cautions, it is easier for those who produce and consume the art to “play along with the culture which gave birth to the murder” and the suffering in the first place (p. 313). Artistic representation of and attribution of meaning to suffering can extend the injustice inflicted upon victims by diminishing the horror;8 and yet, paradoxically, Adorno insists, “no art which tried to evade [the victims] could stand upright before justice” (p. 313).9 Art’s injustice is implicated in the justice it serves. Even works of art that intentionally take the side of suffering victims do not have clean hands, for they too cannot avoid relying upon the Enlightenment rationality utilized in the death camps. Such is the contradiction that renders poetry and art after Auschwitz at once barbaric and morally necessary.

In commenting on Adorno’s view of art, Shoshana Felman affirms the heightened historical and moral responsibilities of art after Auschwitz: “It is only art that can henceforth be equal to its historical impossibility…[Art] alone can live up to the task of contemporary thinking and of meeting the incredible demands of suffering…and yet escape the subtly omnipresent and the almost avoidable cultural betrayal both of history and of the victims” (Felman 1992, p. 34). Art meets these historical and moral responsibilities, she adds, in the creative form of testimony. Holocaust testimony, the predominant literary genre of this generation and paradigmatically represented by Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah, is characterized foremost by fragmentation. Shards of memory signal the overwhelming nature of the traumatic event and the incapacity on the part of the survivor to paint a coherent picture of the destruction personally experienced. Testimony works less as a declarative statement about what is known and more as a performative act about the eluding of memory and meaning associated with trauma that is expressed verbally in the repetition and nonlinearity, gaps and silences of survivors’ accounts. By nature contradictory, incomplete, and in process, Holocaust testimony gives voice to the excessiveness of the suffering that remains inchoate and real (Felman 1992, p. 5).

Felman suggests a further reason for the potency of Holocaust testimony that has implications for understanding art’s connection to justice. “When the facts upon which justice must pronounce its verdict are not clear…and truth and its supporting elements of evidence are called into question,” the courtroom serves as that setting where the crisis of evidence is adjudicated through testimony in service of justice (Felman 1992, p. 6). However, the extremity of Auschwitz raises doubt about justice’s standing. The breaking of bones and bodies signals not merely a crisis of evidence in the dispensing of justice but also a more fundamental crisis of truth in the modern narratives and supporting institutions that justice sustains. Auschwitz means that the narratives of enlightenment and salvation history, and the justice in service to each, crumble under the impossible weight of a million murdered children.10

Art after Auschwitz bears witness then to both personal and cultural damage. It can do so when it thinks against itself by way of contradiction and attends to the weight of material suffering. For the trauma survivor, art can function as a contradictory witnessing presence to the experience of suffering that helps counter, although never erase, the injustice evoked by the experience that can persist (Laub 1992).11 And as art bears witness to suffering that eludes comprehension and defies the attribution of meaning—here the paradox presents itself—it also functions as an inventive, performative act that bears witness to and helps creatively structure the chaos of catastrophe.

3. Bak and Bearing Witness

Holocaust survivor Samuel Bak is one of those important artists of the age, to use Adorno’s phrase, whose artwork bears witness to suffering and loss by creatively structuring chaos. At age 84, and one of only 200 Jews to survive the liquidation of the Vilna ghetto, Bak has for more than seven decades painted the devastation and loss of Jewish self, family, and culture. A child prodigy, and the only living survivor/artist to have exhibited both in the ghetto and Yad Vashem (Bak 1981), Bak has devoted his artistic energies to the task of remembering suffering and of bearing witness to those persons and communities whose names and faces have been erased from memory, in particular the million murdered children. His preoccupation with bodies and worlds—often presented in fragmented and disfigured, impermanent and provisionally reconstructed forms—focuses aesthetic and moral attention on the materiality of loss. The beauty of his paintings is in jarring tension with the barbarity of its content; the effect is to disrupt and demand our attention to actual bodies and worlds. For example, of his nearly 100 paintings of the photographed Warsaw Ghetto Boy, Bak says, “It is no dream world but rather reality experienced and expressed through metaphor” (Raskin 2004, p. 150). The “poignancy of [the boy’s] uniqueness” and “the specific that revolts” ground his effort to paint an individual memorial for each of the million children lost, an impossible effort to recover “a past that can never be fully remembered or forgotten” (Fewell and Phillips 2009a, p. 5). The burden of the empirical is a constant weight holding brush to canvas and Bak to his calling to remember each face, like the nameless Warsaw child, swallowed up in the abyss.12

Bak eschews abstraction in favor of the concrete. He abandoned his early abstract and semi-abstract style for a representational—characterized as pictorial realist or near surrealist—approach because he found the former hindered the telling of his personal story (Bak 2001) and was insufficient for dealing with the immense weight of his experience (Levitan 2017; Pols 2010). By revisiting and re-presenting ancient masters, Jewish cultural artifacts of everyday life, biblical texts and traditions of covenant and creation,13 and secular and religious icons and symbols of promise and hope, Bak presses viewers to address his canvases, his experiences, and the concrete experiences of others’ suffering and loss. Bak’s artwork shares Adorno’s deep misgivings about the Enlightenment project with its undelivered promises of freedom, equality, and progress and the justice enlisted to secure them. And yet, like Adorno, Bak sustains hope14 for a repaired world where Auschwitz is not repeated. The tension between disenchantment and hope permeates Bak’s compositions.

The details of form and content of Bak’s paintings show how he thinks in contradictions and bears the burden of the empirical, the difficult standard Adorno sets for art after the Holocaust. Bak’s distinctive visual grammar, vocabulary, and style give voice to the incomprehensibility of individual lives shorn of normalcy, morality, and justice for which all language fails; suffering’s “mute and inconsequential” character becomes, on Bak’s canvases, a visual address in the representational strategies, textual details, and striking colors that speak to the absences—the injustices—in his life: his murdered childhood friend Samek Epstein, his martyred father, his grandparents massacred in the Ponary woods, his shattered Vilna Jewish community and culture, among others (Bak 2001; Langer and Bak 2007). With particular persons, places, and events as anchors, his canvases offer tenuous constructions of present absences and absent presences that announce his loss of family, community, and world; the ongoing contradictions that permeate his life in the wake of catastrophe; as well as his hope for tikkun olam, the Jewish mystical notion of repair of the world.

Bak represents the tensions and contradictions of absence and presence, suffering and hope in manifold ways. He paints concentration camp musicians playing silently, lonely teddy bears standing sentinel for missing children, birds grounded from flight, living forests wholly excised from the earth, chess pieces frozen to their boards, floating rock formations that defy the laws of gravity, mourning angels whose messages go undelivered, broken and bullet-marked Mosaic tablets that have shed their commandments, impenetrable books and blank canvases that inhibit reading, keys incapable of opening their intended locks; and yet, we also find new growth on desiccated tree branches, concentration camp victims reaching pointedly for a deity’s outstretched hand, ghetto boys bravely effecting their own rescue, and burial shrouds that serve double duty as freedom sails. These are but some of the incongruous compositional elements Bak puts to his canvases in order to paint the contradictions and make the incongruities visible. Repetition and silence, paradox and particularity inform the rhythm and timbre of Bak’s voice in witness to profound personal and cultural injustice. Burdened by the weight of both loss and possibility, Bak addresses us with a palette of beauty and brutality, all creation of a fertile imagination that bears witness to loss. In painting the contradictions Bak structures the loss and testifies to the truth of his suffering.

Art structures suffering by not erasing it. Franz Rosenzweig reminds us that art paradoxically “aggravates the suffering of life and at the same time helps people to bear it,” teaching “us to overcome without forgetting.” Far from erasing trauma or obscuring injury, art overcomes by “structuring suffering, not by denying it. The artist knows himself as he to whom it is given to say what he suffers....He tries neither to keep the suffering silent nor to scream it out: he represents it. In his representation he reconciles the contradiction, that he himself is there and the suffering also is there; he reconciles it, without doing the least debasement of it” (Rosenzweig 2005, p. 399).15 Bak acknowledges this when he says his paintings protect “the sensitive scar of an ancient wound while still remaining true to the knowledge of the wound itself” (Raskin 2004, p. 154). Bak is there in his artwork, and so too the truth of the suffering.

4. Just Is

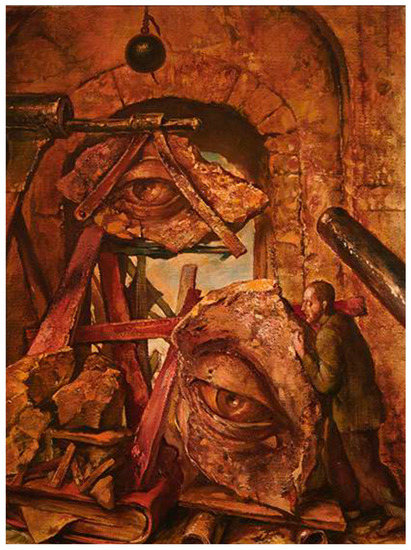

Against this backdrop we begin our exploration of Bak’s Just Is series.16 His title—a word play on justice—offers an important clue as to Bak’s metaphorical imagination. He uses verbal and visual “word plays” extensively in other series to generate possibilities of meaning on the part of his viewers. For example, in his H.O.P.E. series he imbeds the word “HOPE” and in his Still Life series the words “Still Life” amid scenes of devastation and daily life to intensify the tensions between word and image, past and present, life and death.17 In his Just Is series we see a comparable word play in “N Eye for N Eye” where letter and number literally serve as supporting timbers that structure the painted eyes on canvas and challenge the viewers’ eyes in reading the painting. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

N Eye for N Eye, 2015, Bk1971, Oil on canvas.16 × 12″. By Permission of Pucker Gallery.

Word play tensions work because of metaphor—the contrast between unlike things—in which the “is not” of the comparison energizes engagement and creation of meaning. Across his Just Is paintings Bak’s metaphorical imagination is at work in the contrast between iconic figures of justice used before Auschwitz and what Just Is afterwards: past justice and present Just Is differ. The verbal play on words and the visual play on images work in tandem to invite us to respond to the tensions, contradictions, and paradoxes and to decide what sense we will make of them. Importantly, Bak does not prejudge or predetermine our responses.18

In Just Is, a collection of 59 oil on canvas paintings ranging in size from 63 by 38 inches to 9 by 12 inches, all but one produced in 2015, Bak interrogates and reanimates iconic images of Lady Justice and the biblical principle of retributive justice, or the lex talionis, the law of the talion commonly expressed as “an eye for an eye.” By altering the way we see conventional representations of western and biblical justice, he refracts them through the lens of his personal experience as a Holocaust child survivor and in light of modern life marked by atrocity. Bak’s artwork resists narrow labeling as Holocaust painting; his work addresses wider questions of atrocity as a human experience. In the wake of Auschwitz, but also Bosnia, Kosovo, Darfur and the Sudan, he asks what does Lady Justice and the lex talionis now look like in a damaged and disenchanted modern world? Or in Bak’s own words, what suffering wound does justice—reconfigured today as Just Is—bear witness to, and what is asked of viewer and artist to remain true to it?19

5. Just Is and the Atrocity Universe

“The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.” Martin Luther King, Jr.’s iconic words, borrowed from the early 19th century American Transcendentalist preacher Theodore Parker, express unqualified confidence in the spiritual trajectory of life (Parker 1853, pp. 84–85).20 In the moral universe justice exerts a gravitational pull that anchors and buttresses human experience in the face of injustice. The celestial imagery evokes the tradition of the Hebrew Bible prophets with its assurances of God’s universal justice (mishpat) and righteousness (tzedekah) that will be extended to all of creation. God’s promised justice is orthogonal to a desiccated world wracked with violence inflicted upon the weak and the oppressed. This assurance gives the Prophet Amos confidence to imagine that God’s life-giving “justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream” (Amos 5:24, NRSV). King’s moral universe is further bolstered by a Western legal tradition, with its Christian theological roots, grounded in the rule of law and constitutional principles that guarantee justice will be neither delayed nor denied: “No one will we sell, to no one will we refuse or delay, right or justice,” the Magna Carta of 1215 promises. In the moral universe, iconic justice confidently stands by and for the principle that those who suffer injustice and are incapable of standing up for themselves will be protected.

In his Just Is series Bak paints an alternative universe—the atrocity universe—in which the promise of divine justice and assurance of the rule of law, and the culturally familiar icons that have come to symbolize both, are reprised through the lens of his Holocaust experience. In stark contrast to King’s moral universe, Bak presents a monstrous cosmos in which the sanctity of individual and communal life is violated, and suffering now structures human relationships, time, and space. The arc of the atrocity universe bends not toward justice but injustice—the gates of Auschwitz, the fields of Cambodia, the hamlets of Kosovo, the mountains of Rwanda, and the jungles of the Congo. The gravity of past and repeated atrocities presses Bak to question the status of justice’s standing and the viability of any universal ethical demand for public and private justice in the face of life after Auschwitz. Contesting principles of grand Justice, Bak gives us instead a refigured and diminished Just Is.21

In his familiar artistic style, Bak draws upon culturally recognizable icons to interrogate and reanimate them as alternative iconic images appropriated for the atrocity universe. Previous efforts focused on the iconic images of the photographed Warsaw Ghetto Boy,22 the pensive angel in Albrecht Dürer’s engraving Melencolia I,23 and God and Adam’s near touch in Michelangelo’s fresco, The Creation of Adam.24 To that group Bak now adds the pair Lady Justice and the biblical lex talionis. By transforming the standard icons visually emblematic of justice and economic restitution, Bak invites his viewers to think in contradictions and burdened by the empirical about the assumed status of founding religious and juridical symbols and principles, and their purchase upon life—or rather deathlife, to employ Lawrence Langer’s discomforting term—after Auschwitz (Langer 2006, p. 295). Bak asks in concrete terms: What do we imagine justice to look like for six million Jews murdered and those who survived the killers? What weight do the Nuremberg Trials, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, or the Universal Declaration of Human Rights bear upon the scales of justice? What moral force can the repeated promises of the biblical lex talionis exert to restore balance (shalom) to a world where children are tossed into furnaces alive or slaughtered by terrorists in their school rooms? In the post-Holocaust world and the wider atrocity universe that serves as its cosmic home, traditional human and divinely sanctioned justice have been shattered under the weight of unspeakable suffering leaving justice, balance, and restitution emptied of earlier meaning. In our age of on-going atrocity, after Rwanda and Darfur, Srebrenica and Breslan, Paris and Orlando, and now Manchester, Bak asks us to question whether any icon or principle of justice may ever again be meaningful, durable, and comforting. Bak’s Just Is images raise, but do not answer, these vexing questions.

6. Iconic Lady Justice and the Lex Talionis

To more fully appreciate the ways Bak creatively refashions images of Lady Justice and the lex talionis, it is helpful to address the traditional representations of secular and sacred justice that he transforms into icons of Just Is. Lady Justice and the lex talionis belong to a longstanding historical, artistic, and legal tradition. In Western iconography justice is traditionally figured as a young, vital woman crowned with plant sprigs, draped in flowing robes, and, since the sixteenth century, typically blindfolded (Miller 2006, pp. 1–6; Resnik and Curtis 1987, pp. 1727–28). In her left hand she grips a balance scale and in her right a double-edged sword. The blindfold introduces substantial ambiguity into her figure. In principle, blindfolded eyes signify impartiality and fairness, but in practice they can inhibit efforts to determine if scales are properly balanced or how the sword is being wielded. As biblical Esau’s stolen blessing attests, justice can be thwarted by the lack of sight (Gen. 27:1–38). See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Statue of Lady Justice, Palace of Justice, Bruges, Belgium.

Iconic Lady Justice’s origin is ancient and uncertain (Resnik and Curtis 1987, pp. 1729–30; Miller 2006, pp. 1–4). Balance scales and sword link Lady Justice to her Near Eastern and Greco-Roman sister goddesses of justice and morality. The Egyptian goddess Ma’at, the daughter of the sun god Ra, carried a sword but not a scale of justice. Themis, the Greek goddess of divine order, law, and custom and her daughter, Dike, goddess of human justice who maintains social and political order, are both blindfolded and carry scales and sword. The Roman goddess Justitia, who regularly stands vigil atop modern Western courthouse cupolas and guards courtroom entrances, is also depicted with balance scales and sword although she is not always blindfolded.25 In the medieval period the Christian theological consolidation with pagan justice lead to the classical goddesses of justice joining the quartet of Christian cardinal virtues alongside Prudence, Temperance, and Fortitude to become one of the formidable seven theological virtues partnered with faith, hope, and charity (Resnik and Curtis 1987, p. 1728).

The scales Lady Justice holds have an equally uncertain genealogy. The earliest use of scales of justice is to be found in the ancient Egyptian mythological depiction of the judgment of the dead in the Book of the Dead (Miller 2006, pp. 3–6). Anubis judges the fate of the dead whose heart or soul lies in one pan and an ostrich feather belonging to the goddess Ma’at in the other. In popular medieval Christian iconography, St. Michael weighs believers’ souls at the Last Judgment. However, if the scales be tipped or in equipoise what does either portend? The meaning varies depending upon culture and context. In ancient Egypt hearts heavier or lighter than the feather of Ma’at meant immediate demise at the hands of Ammit, the Devourer of souls. For biblical Israel, tipped scales were less the concern than their prior rigging: “A false balance is an abomination to the LORD, but a just weight is His delight,” the writer of Proverbs warns (Prov. 11:1 [NRSV]) (Miller 2006, p. 6). The Prophet Hosea reserved a special condemnation for the merchant who loves to oppress the poor with false balances (Hos. 12:7). However, justice defined according to the principles of equivalence and substitutability, as Adorno remarks, also serve the interests of violence and injustice. Hitler’s order to raze the village of Lidice and exterminate all of its men, women and children in reprisal for the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich was an act of violent equivalence in this instance: 340 souls for one.26

The lex talionis has equally deep roots in antique Near Eastern society (Miller 2006, p. 17). Although its precise origin is also lost to us, the ubiquitous presence of the lex talionis, like Lady Justice herself, suggests a near-universal ethical demand for public and private justice across different cultural systems although its role in these systems varies significantly (Weaver 1992, p. 37; Daube 1956, pp. 25–26; Frymer-Kensky 1980). The talion is cited in the Code of Hammurabi, Middle Assyrian Laws, as well as in Greek, Roman, and Jewish scriptural and rabbinic formulations in the Talmud and responsa literature. In the biblical literature the talion is found in multiple places and forms in the books of Exodus and Deuteronomy, Leviticus and the Gospel of Matthew27 where different combinations of eyes, teeth, hands, feet, lives, burns, wounds, and stripes are paired, weighed, measured, and balanced (Miller 2006, p. 58). Of all the body parts, however, it is the eye that captures the biblical—and so too Bak’s—metaphorical and moral imagination.

A pecuniary sense of the talion replaced a corporal one after the 5th century BCE although the corporal sense of talion returned in medieval Christian Europe and served as legal justification for corporal punishment until the end of the 18th century. In the Rabbinic legal tradition, confirmed by Maimonides, the plain meaning of the Hebrew alliterative phase ayin tachat ayin, “an eye for of an eye,” is unquestionably pecuniary and not corporal: A person who causes injury is responsible for making compensatory restitution to the injured party, thus making whole what was broken, restoring peace or shalom to situations of conflict and disorder (Maimonides 1170–1180; Miller 2006, p. xii; Daube 2000, vol. 2, pp. 178–79; Daube 1947). The weighing of one eye against another, the effort to achieve financial equipoise, affirms the fundamental moral and social responsibility to rebalance the scales, correct injustice, and make life whole (shalom) again.28

But after the Holocaust can the burden of the weight of six million be measured in economic or any terms? What does balance, wholeness, and moral responsibility mean for survivors who live in an atrocity universe anchored by an economy of injustice, not justice? What stature and status do the icons of Lady Justice and the lex talionis have reconfigured for this atrocity universe? Bak now shows us.

7. Bak’s Icons of Just Is: Reading the Images

We meet Bak’s Lady Justice in varying conditions, poses, and garbs juxtaposed to once familiar biblical symbols of covenant, law, and justice. Noachic rainbows and Mosaic tablets of the law, talionic eyes and Hebrew letters combine with female figures and balance scales, blindfolds and swords in ways intended to disrupt our perceptual, conceptual, and moral fields of vision. Bak’s damaged and modified female bodies, defunct and imbalanced scales, and ubiquitous and unblinking stony eyes peer out at us and onto a landscape of devastation that is anything but whole and upon justice that is now virtually unrecognizable.

In By Hook (Figure 3) we encounter Lady Justice in pieces, her body a diminished version of her former iconic self. She no longer stands in her revered place atop the public courthouse dome; instead, we find her fragmented upper torso precariously balanced on a wooden slat atop a stone heap. With arm severed at the elbow, she still manages by hook or by crook to maintain herself and the balance handle upright, quite an impressive balancing act. The configuration gives an ironic twist to a variant of King’s maxim—“The moral arc of the universe bends at the elbow of justice.” Our eye is drawn to the many eyes that dot the canvas inviting us to connect the dots not only between the lex talionis and Lady Justice but both to the scene of wreckage. The slipped blindfold exposes her eye gazing out beyond the canvas frame suggesting Lady Justice is aware of her predicament, which may serve as an analogy to the predicament Bak as artist faces after atrocity: Is she able any longer to stand upright and perform her juridical duties impartially in the midst of such ruin? Is she up to the balancing task? Is Bak’s art up to the task of representing injustice in ways that refuse to be impartial to the suffering it expresses in such radiant colors, textured details, and paradoxical configurations? What is the balance art must achieve between the beautiful and the barbaric?

Figure 3.

By Hook, 2015, BK1939, Oil on canvas, 40 × 30″. By permission of Pucker Gallery.

A lone balance pan contains a second eye, its mate having completely dropped from sight through the tabletop. What could the pan have held that was so weighty as to produce this hole and to leave the balance apparatus in shambles? Yet a third eye peeks out from a half-lidded box as if confronted by the same thought. Are we eyewitnesses to a scene of failed justice or, alternatively, to a damaged, yet determined and persistent Lady Justice, a casualty of the catastrophe still somehow standing her post? The same question can be posed to all art after the Holocaust: Does art stand up for those who suffer, committed not to itself but to others? Bak visually preserves the moral uncertainty inherent in his artwork and in our present context.

In her left hand Lady Justice elevates a hook/question mark extending from the now defunct balance scales. The question mark, a favored element in many Bak paintings, tops the balance handle framed by yet another eye sketched out on a canvas tacked to a wall. Peeking out from behind the eye we barely make out the curved tops of two blank tablets of the law inviting us to wonder why these hinted-at Mosaic tablets remain shrouded. Is this an admission that the covenantal law and its lex talionis proxy cannot bear to look out upon a scene of Jewish devastation? What might it suggest about a Western juridical and Christian theological tradition that appropriates and cultivates Jewish principles of justice all the while demonizing Jews and worse? From yet another perspective might the shrouded Torah evoke the biblical commandment prohibiting the verbal and visual imaging of God (Exod. 20:4–6)? The prohibition of images, a central Jewish mitzvah, was a theological theme that Adorno used to reflect on modern damaged life. Instead of a prohibition against imaging God, he makes it a demand to image the administered world (Adorno 1997, p. 93; Levi 2014, pp. 140–42). Modern racialized anti-Semitism provided the Nazis with justification for erasing Judaism and all things Jewish, even erasure of the murder factories. Who and what, by implication, is missing from this picture, dropped out of sight and history if not the Jews who were made to suffer uselessly? The lex talionis’ wide eye gazes beyond the frame of the canvas searching us for answers to disturbing questions about modern justice, what we see, and, importantly, what we choose not to.

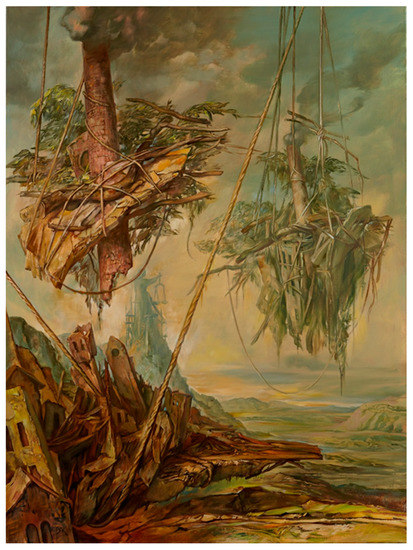

The juridical theme is pronounced in Inadmissible (Figure 4) where Bak presents a full-bodied Lady Justice foregrounded by destruction and standing at a distance from the scene of a massive crime. We confront two belching chimneys, bound up in the wreckage of civilized life, suspended above a floating debris field bundled together and belayed by rope to prevent further collapse. In our minds eye we can see all-too-common Nazi hangings of concentration camp children meant to send the clear message that human life is fungible in the administered world. Our imagination and disbelief about what we see is also suspended. The chimneys mimic and mock the scales of justice and the talionic principle of measure, equivalence, and balance in the atrocity universe: death, not life, is the unbearable unit of measure in this barbarous balancing act that Amos’s prophetic scales could never calibrate. What is entailed in weighing one life, one chimney, one ghetto, one shtetl, one death camp, one atrocity against another? Bak interrupts conceptualizations of genocide that tempt us to compare and equate one suffering with another. Adorno reminds us that only in the administered world that conceives all things, including life and death, as quantifiable and mathematized—tattooed numbers for names, emaciated bodies for units of labor, and medical experiments on children for scientific research—could the measurement of suffering be conceivable. However, the sheer incomprehensibility of such tasks and any metrics we might conjure to make sense completely overwhelms the senses. Bak asks us to consider: How do we go about measuring the loss of two thirds of European culture, or of a Samek Epstein? In what courtroom at The Hague would such horrific evidence be comprehensible, let alone admissible, as evidence at trial? What jurisprudence would presume to have categories of evidence or damages that could apply? The concepts of retribution, restoration, and restitution and the economic principle at the heart of the lex talionis hardly seem functional in view of violence committed on this scale.29 The weight of suffering pictured here defies every measure of meaning and morality, the math too severe to account for the empirical reality.

Figure 4.

Inadmissible, 2015, BK 1931, Oil on canvas, 48 × 36″. By permission of Pucker Gallery.

On a distant promontory Lady Justice stands vigil, a lone symbol of justice once so prominently and powerfully displayed atop courthouse domes yet now brought low by forces of destruction. She appears shrouded with scaffolding, surrounded we can imagine, by lofty principles, ideals, and traditions. Does Bak hint at a possible makeover under way? Is Lady Justice being restored to her former iconic status at the cost of erasing all signs of the devastation she oversaw from her cupola? Is principled justice ironically to be protected from the reality she was tasked to safeguard the innocent from so that she can conceive, and possibly we too, a regaining of her lost gravitas, stature, and standing? Alternatively, we might resist that reading and see instead Just Is “under construction” suggesting we must now find a different way to put justice to work to ensure that those who suffer are remembered and protected, that injustice and suffering are to be regarded as the same thing from Adorno’s perspective (Bernstein 2005), and that the still-belching chimneys should warn us that the horror is not yet over after Auschwitz. Whatever we might make of this uncertain representation, it is clear Lady Justice is turned away from the catastrophe. So we are left to decide if, like so many principled perpetrators and bystanders implicated in the injustice, we will fall back upon treasured traditions to justify averting our eyes from scenes where real life and death hang in such precarious balance.

From canvas to canvas direct encounter with the disturbing realities of Bak’s Holocaust landscape tests the limits of our legal and moral comprehension, and so it should. Because the atrocity of Auschwitz is inconceivable, responsibility demands not a new conceptualization or quantification of the human problem but the immediate dropping of all blindfolds, the abandoning of any pretense of impartiality and objectivity that would serve to mask the suffering and the taking up of action. In Taking Off (Figure 5), Bak repositions Lady Justice from her protected promontory to inside a balance pan now suspended in air along with her stony-eyed companion as if both had just taken off or had been hoisted above the devastation spread beneath and around them. Is this elevated spot her new improvised courthouse perch? If, as we saw in Inadmissible (Figure 4), Lady Justice was able to avoid seeing, now she has little choice, and so too her talionic partner. With mask in hand, Lady Justice peers out over the flooded chasm below suggesting that after the cataclysm the masquerade of innocent justice and the pretense of impartially is over. The detached, matching balance pan holds the remnants of a once vital community that iconic Lady Justice and the lex talionis were in principle charged with, but proved ultimately ineffective in, protecting. Bak paints a graphic reminder that purported icons and principles are only effective when they actually protect; social structures can readily turn a blind eye to, and even become actively complicit in, the worst as the vaunted German legal system and the volkisch German Christian movement amply demonstrated in their advocacy of Nazi genocidal goals. Theological traditions, enlightenment narratives, and legal systems have cultural and historical roots. How do we gain sufficient critical perspective on ours to see the material reality of injustice in front of us?

Figure 5.

Taking Off, 2015, BK 1936, Oil on canvas, 40 × 30″. By permission of Pucker Gallery.

Bak helps us gain perspective on the religious dimensions of the Nazi onslaught against the Jews. A takeoff on the biblical flood story, Bak bears witness to two world-altering deluges, one ancient and the other modern. Receding waters expose two ships grounded on far distant peaks, one with its stacks still actively streaming smoke. Two near-extinction events—the one Noachic, the other Nazi-inspired—disturbingly coincide on Bak’s canvas creating a difficult association. The Noachic ark was a material sign of God’s covenantal commitment to preserve a righteous, blameless man and his family and a promise to fill the earth with life (Gen. 6:9, 17), whereas the Nazi transport was a sign of Hitler’s demonic commitment to end Jewish life and erase all signs of its presence from the face of the earth and to destroy creation in the process. Bak’s metaphorical juxtaposition invites us to consider the ways both Genesis narrative and genocidal ideology, inflamed by two millennia of Christian contempt for Jews, have worked individually and in tandem to erase memory of real suffering and loss.

At the conclusion of the biblical flood story God places a rainbow in the sky as a heavenly sign of God’s commitment to creation and as a reminder never again to annihilate the living with flood waters (Gen. 9:13–6). God’s need to remember seems overly self-conscious and disturbingly self-justifying, an over-assuring promise not to forget made by a deity we later learn is prone to forgetting covenantal partners who suffer by his hand and his neglect. Bak’s artwork makes us self-conscious about our own forgetting and neglect, and the props we may come up with to help us remember. Lady Justice sees the consequence of the deluge before her but what confidence do we have she, like God, can and will remember? What heavenly sign will she count on? In contrast to his other post-deluge representations, Bak paints no rainbow, installs no colorful arc in the heavens that would signal unqualified confidence in the future. Rather, he gives us wafting smoke connected to grounded ships and destruction, focusing our attention on the material remains of Jewish life after atrocity, here on the earth, where suffering is to be encountered. Memory is sharpened by concretion and particularity, and perhaps this is a lesson for God as well: to look down not up, to the ground and not the heavens, at human devastation not starry wonder for that sign. In the juxtaposition of biblical and Nazi destruction narratives floats another troublesome question: where are the missing children in both ark and pan? Why have they been forgotten?

In the foreground Bak’s balance hook resurfaces, detritus washed ashore as a questioning reminder that forgotten victims of atrocity demand our remembering and that those who suffer may not easily differentiate between violence that is divinely versus humanly inspired. What is our responsibility to unmask the ideological and religious causes of and complicity in atrocity, to remember our failures to remember, to think against our treasured assumptions, and to recognize, as the ship’s still-working chimney insists, that, in Adorno’s words, ongoing suffering tolerates no forgetting? Elevated Lady Justice and talionic eye are a visible reminder that standing at a conceptual or physical distance from the world impedes our ability to hear bones break and to bear witness to bodily suffering.

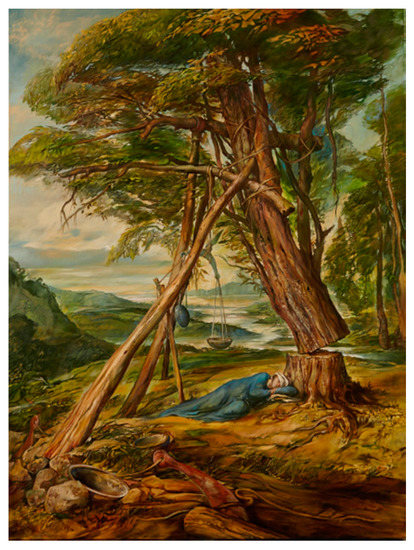

In Nap (Figure 6), Lady Justice, alone for the moment, seeks relief from this unrelenting reality and its implications for religious and juridical traditions, and so do Bak’s viewers. Exhausted by the overwhelming nature of Jewish excision, a situation she paradoxically has had a hand in creating, Lady Justice has abandoned her post to catch a little shut-eye. She stretches out beneath a severed tree improbably propped up by wooden staves to create an unnatural gravity-defying scene that stretches the limits of realism and credulity. Lady Justice seems unaware of the danger that looms directly overhead and perhaps we, too, of the genocides in our time that seem never to take a rest. The incongruous contrast in size between her diminutive figure and the surroundings underscores the puniness of justice’s standing up to the catastrophes. Balance scales hang empty from a detached tree limb. Apparently the tools of vigilant justice need a breather too. Is this is a sign that Lady Justice has rid herself of the responsibility to protect the innocent and to restore life, and if so for what reasons. Is it a matter of utility, or are the very principles of an undersized justice viable in the atrocity universe? After the wholesale erasure of Jewish life and culture, this icon of Just Is presses us to consider whether the response to suffering is a precarious balancing act owing as much to irrational as rational factors. After all, would it not be a relief to justify the paroxysms of violence against Jews over the centuries as mythical irrationality that has run its course rather than as enlightened reason on the part of a Nazified Christian European culture hell-bent on erasing all Jewish life? Would chimerical anti-Semitism (Langmuir 1990, pp. 14–15) or instrumental rationality, a focus of Adorno’s attention, offer the more satisfying theory of the destruction? Which explanation allows her and us to sleep better?

Figure 6.

Nap, 2015, BK 1929, Oil on canvas, 48 × 36”. By permission of Pucker Gallery.

The concept of sleeping justice runs deeply counter to the juridical expectations of an ever-vigilant Lady Justice, supposedly ever-protective and ever-alert to danger. However, as Bak repeatedly intimates, the innocent may no longer rightly count on justice as protector or its icons as assuring. We recall once again that the biblical corpus preserves scars of its many ancient wounds, experiences of past disasters and disappointments with its own sleeping and forgetful divine protector. The Psalmist charges Yahweh, who supposedly neither slumbers nor rests, with sleeping though the oppression and affliction of his people (Ps. 44:23–5). Later the Psalmist sarcastically laments the absence of Yahweh’s saving help that must surely be known only in the land of forgetfulness (Ps. 88:12). Where were the covenantal and constitutional protectors when defenseless Jewish children needed them most? With justice now prone on the ground can we expect any promise of protection, any Torah, any Magna Carta and the icons that used to stand for them to stand up against present dangers? It is left to art, as Adorno asserts, and artists like Bak show to challenge us not to forget and to give voice, consolation, to the suffering. Bak’s paintings remind us that memory work is exhausting and threatening, and that the lack of consciousness and conscience, which often go hand-in-hand, only extends the forgetting and the violence. The burden of the empirical and the burden of memory are linked, and they rest not only with the artist but also with those of us who engage Bak’s art.

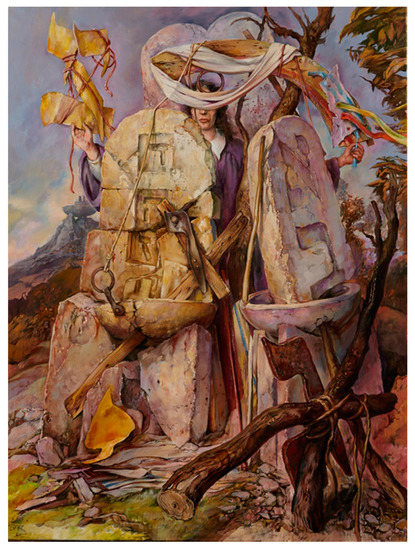

If anything, Bak’s foray into representations of Just Is shows us that Lady Justice’s standing—or non-standing—is far more than a juridical matter but touches upon the very foundations of religious life and thought. Bak pursues the question of justice’s standing in By Law (Figure 7) with its dense constellation of religious symbols and signs that intensifies the work of bearing witness. Compressed around Lady Justice are the familiar symbols of the Noachic and Mosaic salvation narratives, and the Torah, Talmud and kabbalistic texts, in marked conditions of disorder and disrepair. It is not clear whether these fragments affirm or accuse her. She elevates in her one hand the Hebrew letter tsade—in Yiddish tzadik stands for “righteous person”—and in her other a rainbow-colored Noachic arch beneath which hang suspended incomplete and fractured tablets of the law. As an act of Jewish midrash Bak invites us to connect Lady Justice as the tzadik described in the Zohar as the “Righteous one who suffers” to the vibrant Lurianic kabbalistic tradition with its vast cosmogony intended to explain the reality of exile and evil in the world where God has been shattered into the ten sefirot. Is she one of the 36 tzadikim nistarim, the anonymous righteous ones that the Talmud confidentially assures lives in the damaged and fallen world among us at all times? She may be a mixed reminder that evil does not have the last word and that restoration of the world, tikkun olam, is possible through the re-gathering of the sefirot, the shards, and the restitution of God.

Figure 7.

By Law, 2015, BK 1930, Oil on canvas, 48 × 36″. By permission of Pucker Gallery.

Lady Justice’s wooden sword is oddly sheathed in the balance pan supporting one of two Mosaic tablets. The letter vav, the sixth letter/commandment signifying the biblical prohibition against murder, is riveted through the sword handle, a jolting connection between biblical law and mass murder, a trope Bak repeatedly explores elsewhere. Behind Lady Justice our eye catches sight of another set of pristine tablets blindfolded by a cloth-draped broken rainbow, the intersection of two covenantal symbols of promise that Bak’s atrocity universe now vacates.

Perched on a distant mountain peak we make out the silhouette of a ship that once again recalls the biblical flood narrative and the salvation of Noah, that righteous man blameless in his generation (Gen. 6:9), and who survived the deluge with his family intact. In an unsettling contrast we can imagine the S.S. St. Louis, that modern Jewish ark that failed to deliver to safety its human cargo of 937 blameless Jewish children and adults seeking safe haven from the Nazi calamity. We are reminded yet again that the biblical narrative makes no mention of children brought to safety (Fewell and Phillips 2008b, p. 84) and that the Genesis narrator included them among wicked humankind whose minds and hearts were evil all the times (Gen. 5:5). Whereas the kabbalistic tradition struggles to nuance the problem of evil, “[n]either the Bible nor the Nazis make any distinctions, or exceptions, in their zeal to solve the problem of ‘evil’ and ‘pollution.’ And there is nothing in Jewish or Christian theology that can make satisfactory sense of it. No lex talionis, no Torah of any kind, can bring [the children] justice” (Fewell and Phillips 2008b, p. 84). Nothing. The double smokestacks stand as a sobering reminder that Sobibór and Auschwitz, not Havana and Miami, were the final ports of call for many of the S.S. St. Louis’s murdered and never found. By the standards of 1939 international law, the refusal of sanctuary may have been legal, but after Auschwitz by what moral law and in what moral universe could we ever call the suffering of children justifiable? Bak’s atrocity universe and Just Is icons leave us with this unsettling question: when will we cease our theodical pretense at “squeezing any kind of sense, however bleached, out of the victims’ fate” (Adorno 1992, p. 361)?30 For when we justify suffering or account for evil using symbols and narratives that distance us from the reality, we are complicit in erasing the names from the ship’s passenger manifest.

Across his many canvases in this engaging series, Bak exploits biblical letters, symbols, and experiences of covenant to fashion his alternative icons of Just Is. For example, in Scripture (Figure 8) Lady Justice holds up the letter ayin (literally “eye”) written on a page in Hebrew cursive and Phoenician pictograph; and in Ever-Ready (Figure 9) she is dwarfed by tablets of the law inscribed with the familiar double yods, the unutterable name of God,31 that can also be read discomfortingly as double vavs, the repeated sixth letter/commandment prohibiting murder. Bak relies upon repetition as a trope on his canvases: multiple representations of Lady Justice, letters, eyes, tablets, covenants, balance scales, ropes, swords, ships, scrolls, carts, pans, faces, arms, and masks. These iterations, not unlike the numerous appearances of Lady Justice and the lex talionis across multiple cultures, historical periods, legal systems, and biblical texts, may signal something indirectly about the anxiety attendant to promises of justice and shalom shaken by genocide and atrocity past and present. It is inviting to see Bak’s iterations (Fewell and Phillips 2009a, p. 5) as a kind of visual stutter, a manifestation of what Freud describes as repetition compulsion related to past traumatic experience (Freud 1920, p. 20). Bak’s paintings return repeatedly to scenes of devastation and injustice. He repeats the same tropes and themes. Might the iterations of his icons of Just Is reflect that Jewish aniconic impulse to negate and destabilize every image, not in this case of God but of justice? Might they be his way of constructively remembering, repeating, working through, and witnessing to old wounds?32 Bak involves us in that memory work. He reiterates the figures of Lady Justice and the talionic eye now as diminutive Lady Just Is and plucked out, unblinking talionic eye, reconfigured by and for an atrocity universe where the lofty promises of Enlightenment and biblical justice have not been realized, where delay and denial are the reality, and restitution unachievable. We should resist the temptation to reduce these icons of Just Is to Bak’s psychological neediness but instead see them as fortifying acts of memory and moral courage. They encourage us to stand up to an atrocity universe with heightened moral realism and honesty, no longer suffering under a romanticized illusion of iconic Lady Justice and talionic restitution. Art that remembers suffering is art that “stand[s] upright before justice” (Adorno 1985, p. 314). Bak’s artwork holds out hope for this possibility.

Figure 8.

Scripture, 2015, BK 1938, Oil on canvas, 40 × 30”. By permission of Pucker Gallery.

Figure 9.

Ever Ready, 2015, BK 1942, Oil on canvas, 40 × 30″. By permission of Pucker Gallery.

Bak explores this possibility in Long Lasting (Figure 10) where we catch a commanding view of the atrocity universe surrounding iconic Lady Just Is. Retrieving another favored image, Bak fashions the Holocaust world as a pear pealed apart to expose its sphere cored out, its central contents exploded before our very eyes. The traditional hoped-for restoration of God’s universal justice (mishpat) and righteousness (tzedekah), appears now an empty dream, a permanent disjuncture from the present reality of damaged life. In this arid setting Amos’s vision of rolling waters and ever-flowing stream of divine justice seems little more than a pipe dream, some opiate-induced hallucination needed to escape from reality.

Figure 10.

Long Lasting, 2015, BK 1941, Oil on canvas, 40 × 36″. By permission of Pucker Gallery.

Positioned before a belching crematory chimney, Lady Just Is stands unblindfolded, able to see the shattered world surrounding her. She seems on the cusp of doing something. Posed to descend a short flight of steps, she directs herself toward what appears to be a repositioned—maybe repurposed—tablet of the law propped up against a landing. Bak paints a modern post-Holocaust Mt. Sinai wrapped not with kiln smoke that went up because God had descended upon the mountain with fire (Exod. 19:18) but with crematory smoke of Jews wafting skyward as a consequence of the Nazi destruction that descended upon them.33 In a re-presentation of the Exodus narrative’s central scene, it is Lady Just Is, rather than Moses, who descends the mountain in the direction of a blank tablet marked by bullet holes and reflecting the terrain colors at its base. Does the tablet await a third, post-biblical inscription of the Law this time with a different mitzvah, a new categorical imperative (Ostrove 2013) that gives primacy to this worldly suffering inscribed not by the finger of God, or by Moses’ hand, but with the paint brush of a Holocaust child survivor who incomprehensibly escaped the fate that descended upon a million other children?34 If once upon a time Kant articulated the Enlightenment’s categorical imperative of human freedom, then “Hitler has imposed a new categorical imperative upon humanity in the state of their unfreedom: to arrange their thinking and conduct, so that Auschwitz never repeats itself, so that nothing similar ever happen again” (Adorno 1992, p. 365). Lady Just Is may just be arranging her and our thinking and conduct to express a new moral law, a new Torah, a new Bible, a new talion, a new universe, a new Just Is.35 Standing dead center in the midst of, not above or at a remove from, the destruction, Bak asks if she, and we, are ready to face this damaged world. As with much of Bak’s representation of loss, we remain unsure yet hopeful.

Our uncertainty and hope only intensifies as we conclude our exploration with Eye for an Eye (Figure 11) and its implications for retribution and restitution in the face of atrocity. Here we witness the consequences of a justice that has presumably fallen out of the hands of an impartial Lady Justice and into those of partisan crowds. She is not visible in this frenzied scene, perhaps absorbed off canvas with her own affairs or blended back into the crowd; we can’t be sure. Set incongruously in a bucolic setting amid rolling hills and lakes, two carts stand nose to nose suggesting a scene of confrontation with each bearing down upon the other, eye to eye. Clustered behind each cart are gathering crowds pressing forward under the banner of their respective causes although tellingly both banners are blank. If they intend to promote some particular ideology or cause they have apparently lost the language for it. We wonder if we are witnessing two clashing communities on the brink of violence and yet further suffering. We could imagine each side getting set to settle the score, to exact a literal talion by taking the other’s eye in payback for some wrong, to balance the scales violently, certainly one understanding of the ancient tradition of the talion. In their haste they may not even be aware that the wheels have come off their transports, and that metaphorically when the wheels come off, when the icons no longer effect peace, when domination over the other, governs our communal lives together, that they perpetuate a suffering world where the literal loss of an eye, tooth, hand, and foot is sure to escalate to more horrific losses of life and limb, culture and creation. Is Bak indicating that the wheels of justice no longer turn and that that they have come off the Enlightenment and theological narratives along with their icons?

Figure 11.

Eye for an Eye, BK 1932, Oil on canvas, 36 × 48″. By permission of Pucker Gallery.

From a different perspective we might see instead two opposing parties raising the iconic white flag of peace with the implications that the violence toward the other has given way to being for not against the other—an eye for an eye. If so, we can imagine that the crowds might see, perhaps for the first time, the consequences of taking justice, the narratives of freedom and salvation, and their supporting icons into their own hands and have pulled back from the brink. Is it possible we are witnesses to a scene of collaboration, not confrontation, in which the crowds have linked their individual eyes together in a promising act of community and a parallax moment of shared vision? A single eye on its own is incapable of discerning distance or depth; depth perception requires two eyes working together, one with and for the other. It is a promising thought. However, even with two eyes perception is not always assured. It Just Is possible that despite best intentions the vision may not be clear enough, that thinking in contradictions may not be critical enough, and the art may not witness effectively enough to remember the suffering. That possibility also exists. As Bak’s two eyes turn toward us he asks if we see the uncertainty but also the possibility of life in a damaged world.

8. Living After?

Along with Adorno’s statement that writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric comes the question, Can we live after Auschwitz? (Adorno 2003, p. 435). Bak’s artwork poses the same question performed in his paintings as a testimony to suffering. After genocide and mass murder we live with continuing unsurety and the ethical demand to remember. We live with a Just Is that we may no longer recognize. We live with legal traditions and biblical principles that are implicated in damage done to the world. And we live today with those who suffer at the hands of people who have traded rifle butts for hijacked airplanes and bullets for a suicide bomber’s vest. With peace in tatters, Bak shows us the pieces, fragments of his and our damaged world, and that is what we all have left to work with living after Auschwitz. Bak’s art addresses us with representations of remnants of justice as a Just Is emerging from and in response to the wreckage that bears witness to the past and to a possible future. In this way, his icons of Just Is offer a tenuous way forward toward living after with art not detached from but in touch with reality, not forgetful of but remembering suffering and its attendant costs.

Samuel Bak’s artwork leaves us with the predicament and precariousness of choice. Bak prompts difficult questions about the nature and work of justice after atrocity that refuses to yield either to easy dismissals of art or confident assumptions about the bent of morality. The refusal to forget or evade suffering, Adorno reminds us, enables art honestly “to stand upright before justice” (Adorno 1985, p. 314); by refusing to forget or evade suffering Bak’s art stands upright before Just Is. The density and complexity of the realities he renders on canvas challenge us to think against pre-Auschwitz thinking, to embrace the burden of the empirical, and to hear and to see the familiar and the given now in unconventional terms. The metaphorical effect is increased aural, visual, and moral acuity; a creative witnessing to suffering and trauma; and above all a call to action. When we now hear the word justice as Just Is and see the icons of Lady Justice and the lex talionis in such altered forms we could choose to resign ourselves to the fact that the justice’s promises are silent. Or, following Bak’s artistic and moral invitation, we could choose instead to hear in his voice and see in his paintings possibilities of alternative icons of Just Is that enable us to bear witness to injustice and challenge us to take up the collective work of restoring shalom to this damaged, not some fabulous yonder, world. With eyes wide open and icons provisionally refashioned for the uncertain work ahead, Bak places the loss and repair of this suffering world, of tikkun olam, before our eyes and in our hands leaving us to decide what our next step will be.

Acknowledgments

I thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions. I also want to express my deep appreciation to Bernie Pucker, Owner and Director of Pucker Gallery, for permission to reproduce images from Samuel Bak’s Just Is exhibition and to adapt elements of my catalogue essay for this publication. But above all, I am grateful beyond words to Samuel Bak for his insistent critical eye and creative courage to bear witness and to bring the realities of genocide and atrocity to his canvases for all viewers to engage.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Adorno, Theodor W. 1985. Commitment. In The Essential Frankfurt School Reader. Edited by Andrew Arato and Eike Gebhardt. New York: Continuum, pp. 300–18. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, Theodor W. 1992. Negative Dialectics. Translated by E. B. Ashton. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, Theodor W. 1997. Aesthetic Theory. Translated by Robert Hullot-Kentor. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, Theodor W. 2003. Metaphysics: Concepts and Problems. In Can One Live After Auschwitz. A Philosophical Reader. Edited by Rolf Tiedemann. Translated by Rodney Livingstone. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 427–69. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, Theodor W. 2005. Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life. Radical Thinkers Classics. Translated by E. F. N. Jeffcott. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Bak, Samuel. 1981. An Arduous Road 60 Years of Creativity. Available online: https://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/bak/intro.asp (accessed on 30 May 2017).

- Bak, Samuel. 2001. Painted in Words. A Memoir. Boston: Pucker Art Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, Daniel Coluccieller. 2017. Theodor Adorno. In Religion and European Philosophy: Key Thinkers from Kant to Žižek. Edited by Philip Goodchild and Hollis Phelps. New York: Routledge, pp. 127–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, J. M. 2001. Adorno: Disenchantment and Ethics. Modern European Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, J. M. 2005. Suffering Injustice: Misrecognition as Moral Injury in Critical Theory. International Journal of Philosophical Studies 13: 303–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daube, David. 1947. Lex Talionis. In Studies in Biblical Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 102–53. [Google Scholar]

- Daube, David. 1956. New Testament and Rabbinic Judaism. New York: Wipf and Stock. [Google Scholar]

- Daube, David. 2000. Eye for Eye. In New Testament Judaism. Collected Works of David Daube. Edited by Calum Carmichael. Berkeley: University of California Press, Volume 2, pp. 177–86. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, Andrew. 2007. The Art of Useless Suffering. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 10: 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felman, Shoshana. 1992. Education and Crisis or the Vicissitudes of Teaching. In Testimony: Crisis of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis and History. Edited by Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fewell, Danna Nolan, and Gary A. Phillips. 2008a. Bak’s Impossible Memorials: Giving Face to the Children. In Representing the Irreparable: The Shoah, the Bible and the Art of Samuel Bak. Edited by Danna Nolan Fewell, Gary A. Phillips and Yvonne Sherwood. Boston: Pucker Art Publication, pp. 92–123. [Google Scholar]

- Fewell, Danna Nolan, and Gary A. Phillips. 2008b. Genesis, Genocide and the Art of Samuel Bak: “Unseamly” Reading After the Holocaust. In Representing the Irreparable: The Shoah, the Bible and the Art of Samuel Bak. Edited by Danna Nolan Fewell, Gary A. Phillips and Yvonne Sherwood. Boston: Pucker Art Publication, pp. 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Fewell, Danna Nolan, and Gary A. Phillips. 2009a. Icon of Loss: The Haunting Child of Samuel Bak. Boston: Pucker Art Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Fewell, Danna Nolan, and Gary A. Phillips. 2009b. From Bak to the Bible: Imagination, Interpretation, and Tikkun Olam. ARTS: The Arts in Religious and Theological Studies 20: 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, Sigmund. 1920. Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Standard Edition ed. Translated by James Strachey, Anna Freud, Alix Strachey, and Alan Tyson. London: Hogarth Press, Volume 24, pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Frymer-Kensky, Tikva. 1980. Tit for Tat. Biblical Archeologist 43: 230–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, Robert. 2002. Unjustifiable Suffering. In Suffering Religion. Edited by Robert Gibbs and Elliott R. Wolfson. New York: Routledge, pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hejinian, Lyn. 2000. The Language of Inquiry. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, Klaus. 2005. Poetry after Auschwitz—Adorno’s Dictum. German Life and Letters 58: 182–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horkheimer, Max, and Theodor W. Adorno. 2002. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Philosophical Fragments. Edited by Gunzelin Schmid Noerr. Translated by Edmund Jephcott. Culture Memory in the Present. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jay, Martin. 1984. Adorno. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, Lawrence L. 2006. Using and Abusing the Holocaust. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, Lawrence L., and Samuel Bak. 2007. Return to Vilna in the Art of Samuel Bak. Boston: Pucker Art Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Langmuir, Gavin I. 1990. Toward a Definition of Antisemitism. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laub, Dori. 1992. Bearing Witness or the Vicissitudes of Listening. In Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History. Edited by Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Laub, Dori, and Dan Podell. 1995. Art and Trauma. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 76: 991–1005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Levi, Neil. 2014. Modernist Form and the Myth of Jewification. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, Primo. 1996. Survival in Auschwitz. Translated by Stuart Woolf. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 1988. Useless Suffering. In The Provocation of Levinas: Rethinking the Other. Edited by Robert Bernasconi and David Wood. New York: Routledge, pp. 156–67. [Google Scholar]

- Levitan, Eliat Gordon. The Ghosts of Samuel Bak. Vilna Stories. Available online: http://www.eilatgordinlevitan.com/vilna/vilna_pages/vilna_stories_s_bak.html (accessed on 30 May 2017).

- Maimonides, Moses. 1170–1180. Laws of Wounds and Damages. Available online: http://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/1088908/jewish/Chovel-uMazzik-Chapter-One.htm (accessed on 30 May 2017).

- Miller, William Ian. 2006. Eye for an Eye. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nosthoff, Anna-Verena. 2014. Barbarism: Notes on the Thought of Theodor W. Adorno. Critical Legal Thinking. Law and the Political. Available online: http://criticallegalthinking.com/2014/10/15/barbarism-notes-thought-theodor-w-adorno/ (accessed on 30 May 2017).

- Ostrove, Geoff. 2013. Adorno, Auschwitz, and the New Categorical Imperative. Perspectives on Global Development and Technology 12: 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Theodore. 1853. Of Justice and the Conscience. In Ten Sermons of Religion. Boston: Crosby, Nichols and Company, pp. 66–101. Available online: https://archive.org/stream/tensermonsofreli00inpark/tensermonsofreli00inpark_djvu.txt (accessed on 30 May 2017).

- Pols, Elizabeth. 2010. Beyond Time: The Paintings of Samuel Bak. Paken Treger. Magazine of the Yiddish Book Center. Spring. Available online: http://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/language-literature-culture/pakn-treger/beyond-time-paintings-samuel-bak (accessed on 30 May 2017).

- Pritchard, Elizabeth. 2002. Bilderverbot Meets Body in Theodor W. Adorno’s Inverse Theology. The Harvard Theological Review 95: 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskin, Richard. 2004. A Child at Gunpoint. A Case Study in the Life of a Photo. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Resnik, Judith, and Dennis E. Curtis. 1987. Images of Justice. The Yale Law Journal 96: 1727–72, Faculty Scholarship Series. Paper 917. Available online: http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/fss_papers/917/ (accessed on 30 May 2017).

- Rosenzweig, Franz. 2005. The Star of Redemption. Translated by Barbara E. Galli. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, John K. 2015. The Failures of Ethics. Confronting the Holocaust, Genocide and Other Mass Atrocities. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg, Michael. 1997. After Adorno: Culture in the Wake of Catastrophe. New German Critique 72: 45–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, Carl B. 2011. The Acknowledgement of Transcendence: Anti-theodicy in Adorno and Levinas. Philosophy and Social Criticism 37: 273–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, Dorothy Jean. 1992. Transforming Nonresistance: From Lex Talionis to “Do Not Resist the Evil One”. In The Love of Enemy and Nonretaliation in the New Testament. Edited by Willard M. Swartley. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, pp. 32–71. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Adorno cites the question of a young resistance fighter character in Jean Paul Sartre’s play Morts Sans Sépulture to critique his advocacy of so-called politically “committed” literature that Adorno argues is disconnected from material suffering. |

| 2 | Adorno identifies with the Marxist oriented Frankfurt School of Critical Theory and promoted a philosophical and materialist critique of modernity with focus on topics that included instrumental rationality, aesthetics, suffering/injustice, fascism, authoritarianism, anti-Semitism, the administrative world, and the culture industry. His contributions to aesthetic theory and postwar Germany educational reform are significant. A detailed engagement with Adorno’s fulsome philosophical and political critique of the Enlightenment project is beyond the scope of this essay. For excellent overviews see (Jay 1984; Bernstein 2001). This essay focuses particularly on Adorno’s views on the connection of art to suffering. |

| 3 | Adorno equates suffering or damaged life with injustice. He rarely uses the latter term preferring “suffering” because it allows him to avoid conceptual abstraction and reification, a major concern in his critique of modernity. See (Bernstein 2005, p. 304). |

| 4 | Self-critical art is required to be socially transformative. See Barber’s discussion of negative dialectics and the role negation plays in Adorno’s rejection of art not in tension with the world (Barber 2017, p. 131; Adorno 1992, p. 10). |

| 5 | On Adorno’s multiple and changing statements about the barbarity of poetry and the different ways it has been interpreted and misinterpreted see (Rothberg 1997; Hofmann 2005). (Adorno 1997, p. 362) eventually clarifies the statement: “Perennial suffering has as much right to expression as a tortured man has to scream; hence it may have been wrong to say that after Auschwitz you could no longer write poems.” See (Hejinian 2000, p. 334, note 3). |

| 6 | For Adorno, “thinking against itself” (Adorno 1997, p. 365) is shorthand for dialectical thinking that applies reason negatively to interrogate the form of rationality that supports oppressive economic systems and establishes conditions that culminated in the administered world of Auschwitz. Thinking must be measured against the extremity of suffering. This is art’s special contribution. |

| 7 | Margaret Bourke-White’s iconic photographs of the Buchenwald camp liberation come to mind. Langer acknowledges art’s central paradox: “art signals its limited success through ultimate failure” (Langer 2006, p. 81). Gibb’s speaks of the “Janus face of art” (Gibbs 2002, p. 31). |

| 8 | The ethical challenge in making suffering meaningful is the focus of Emmanuel Levinas’s phenomenological analysis of useless suffering, theodicy, and ethical responsibility for the one who suffers for nothing (Levinas 1988, p. 158). Suffering is “useless” because it violates the integrity of the person as a self and escapes the capacity to incorporate it into meaningful communicative structures. On the connections to Adorno see (Edgar 2007). On the chastened view of ethics in light of 20th century atrocity see (Roth 2015, pp. 98–101). |

| 9 | By emphasizing negation Adorno avoids conceptualizing justice by first attending to particular material experiences. Bernstein suggests that Adorno gives primacy to injustice over justice (Bernstein 2005, p. 319). |

| 10 | The making of any assertion about the “meaning” of Auschwitz given claims about the meaninglessness of suffering is an instance of a statement that calls for a negating thinking against itself as a way to avoid settling generalizations and to be responsible to those who suffer. |

| 11 | (Laub and Podell 1995, p. 991) propose the designation “art of trauma” in their psychological analysis of artistic responses to trauma. Claude Lanzmann is an instance. Their approach is suggestive and not developed in this essay. |

| 12 | Bak resists the banalization and cultural exploitation of the famous Warsaw Ghetto photo and by implication the real child captured by the Nazi photographer (Raskin 2004, p. 151; Fewell and Phillips 2009a). |

| 13 | For more on Bak’s explicit engagement with biblical themes of Torah, covenant, and creation see (Fewell and Phillips 2008a, 2008b, 2009a, 2009b). |

| 14 | See Bak’s extensive exploration of this theme in his series “H.O.P.E. I” (http://puckergallery.com/artists/Bak_hope%201/bk1693_hope_images.html) and “H.O.P.E. II” (http://puckergallery.com/artists/Bak_hope%202/bak_hope%202_all.html (all accessed on 30 May 2017). On Adorno’s hopefulness see (Bernstein 2001, pp. 429–36). |

| 15 | For further discussion see (Gibbs 2002, p. 6). |

| 16 | Bak continues his Just Is work in a second series of paintings and drawings entitled Just Is II. This essay focuses exclusively on his first Just Is series. To access both sets of exhibition images and interpretive essays see http://puckergallery.com/artists/bak_index/bak_exhibit.html (accessed on 30 May 2017). |

| 17 | See his word play in the series “Still Life” (http://puckergallery.com/artists/bak_stilllife/bk1059_stilllife_images.html) (accessed on 30 May 2017). Bak’s compositions certainly invite allegorical readings, and Bak uses allegory in naming his works. I focus on metaphor primarily because it forefronts the tensions and conflicts tied to negation in the act of comparison, and it points to the concrete symbols he employs. This is not to say allegory does not communicate metaphorical tension and concretion. |