Development and Validation of a Scale for Christian Character Assessment of University Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Research Procedure

2.1.1. Factor Development

2.1.2. Item Development and Content Validity

2.1.3. Pilot Study

2.2. Research Subjects

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Data Screening

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

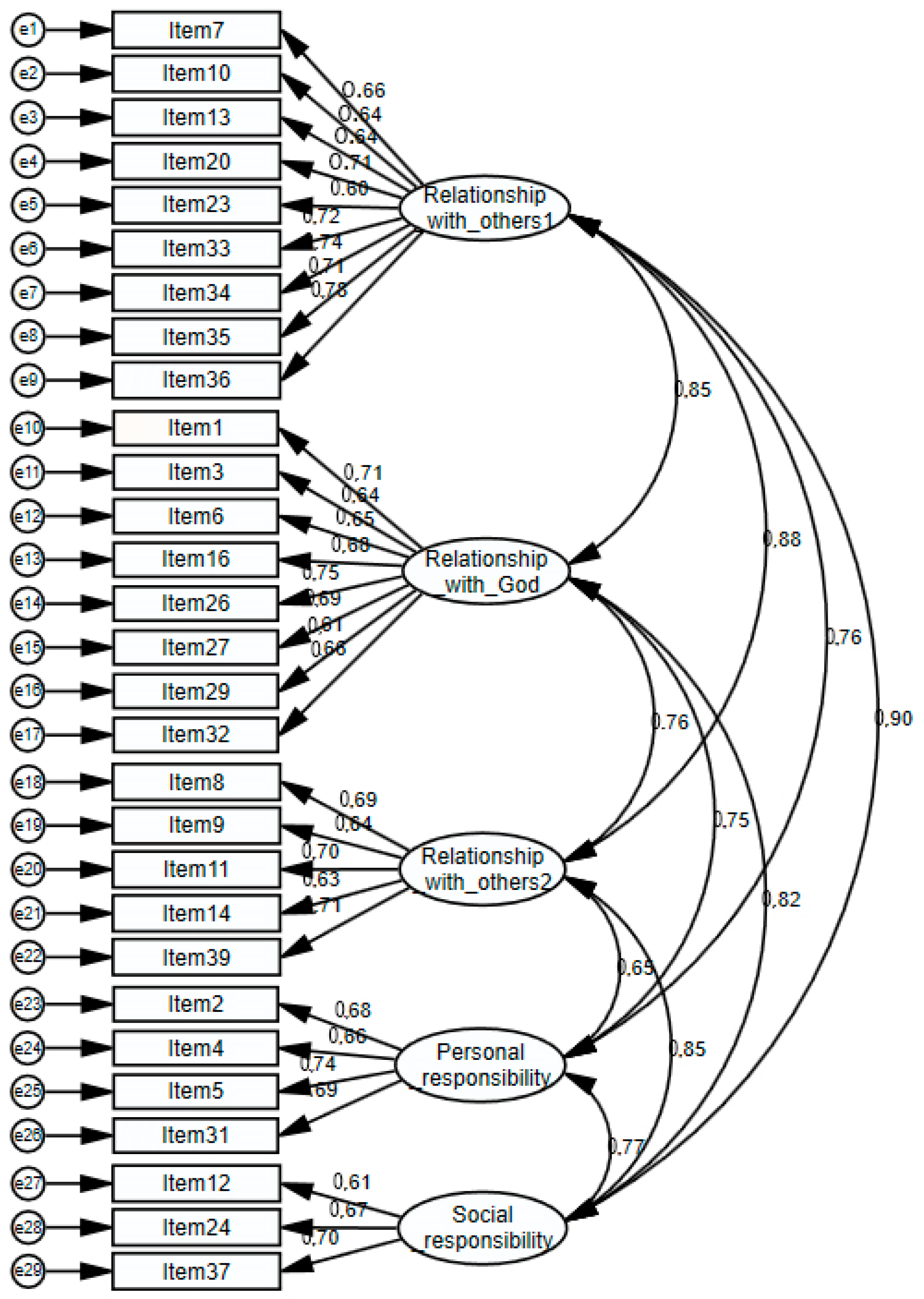

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3.1. Model Fit

3.3.2. Convergent & Discriminant Validity

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Assess-Yourself.org. 2016. Christian Character Index. Available online: http://www.assess-yourself.org/survey/cci/ (accessed on 2 May 2016).

- Calvin College. 2016. Calvin Virtues. Available online: http://www.calvin.edu/~rbobeldy/idis110/sardine/virtues.htm (accessed on 9 May 2016).

- Cho, Chul-Ho. 2015. Structural Equation Modeling Using SPSS/AMOS. Seoul: Chung-Ram. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Yong-Hoon. 2016. A study on character education in the Christian universities. University and Mission 31: 227–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dockery, David S. 2008. Renewing Minds: Serving Church and Society through Christian Higher Education. Nashville: B & H Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Field, Andy. 2009. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gable, Robert L. 1993. Instrument Development in the Affective Domain, 2nd ed. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, David W. 2000. Becoming Good: Building Moral Character. Downers Grove: IVP Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, David W. 2004. Doing Right: Practicing Ethical Principles. Downers Grove: IVP Books. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Ronald, and Klaus Issler. 1992. Teaching for Reconciliation: Foundations and Practice of Christian Educational Ministry. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Sang-Jin. 2014. The importance of personality education for church education. A Journal of Christian Education in Korea 40: 167–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handong Global University. 2016. Core Values. Available online: https://www.handong.edu/about/vision/V2020/values/ (accessed on 9 May 2016).

- Hooper, Daire, Joseph Coughlan, and Michael R. Mullen. 2008. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6: 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Yong-Won. 2015. Biblical foundation of Christian character education. Journal of Christian Education and Information Technology 47: 361–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Chan Mok. 2013. An analysis of the effect of the perceived level of Christianity education on spirituality and humanity. Logos Management Review 11: 221–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, Rex. B. 2011. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press.

- Korea Ministry of Government Legislation. 2017. The Character Education Promotion Act. Available online: http://www.law.go.kr/lsSc.do?menuId=0&p1=&subMenu=1&nwYn=1§ion=&tabNo=&query=%EC%9D%B8%EC%84%B1%EA%B5%90%EC%9C%A1%EC%A7%84%ED%9D%A5%EB%B2%95#undefined (accessed on 17 January 2017).

- Langer, Richard, M. Elizabeth Lewis Hall, and Jason McMartin. 2010. Human flourishing: The context for character development in Christian higher education. Christian Higher Education 9: 336–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Euna. 2015. Criticisms of and alternatives to character education: From homo-economicus to homo-reciprocan. Journal of Institute for Social Sciences 26: 235–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Yunson, Heyoung Kang, and Sojung Kim. 2013. A validation study of the character index instrument for college students. Journal of Ethics Education Studies 31: 261–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Clive Staples. 2015. Abolition of Man. New York: HarperOne. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Hyunjin. 2015. Verifying the Structural Relationship among Creativity and Integrity, Metacognition, Mastery-Approach Goal, Communication Skills, and Autonomous Educational Climate at the College Level. Ph.D. dissertation, Ewha Women’s University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, Eun Kyung. 2015. The religious value of character education and its application through hidden curriculum. A Journal of Christian Education in Korea 44: 49–76. [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, Julie. 2010. SPSS Survival Manual, 3rd ed. New York: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Sung-Mi, and Sung-Hee Huh. 2012. A study for development of the integrated humanity scale for adolescent. The Korean Journal Child Education 21: 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Pattern, Mildred L. 2001. Questionnaire Research: A Practical Guide, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Pyrezak Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, Mark, Thomas Lickona, and Victoria Nesfield. 2015. Narnian Virtues: C.S. Lewis as Character Educator. Journal of Character Education 11: 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Son, Kyung Won, and Changwoo Jeong. 2014. A study on the analysis of Korean adolescent’s character and its implications for character education. Journal of Ethics Education Studies 33: 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- The Church of England Education Office. 2015. Fruits of the Spirit: A Church of England Discussion Paper on Character Education. London: The Church of England Education Office. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton College Center for Vocation and Career. 2015. Wheaton College Center for Vocation and Career: 2015–2016 Catalog. Wheaton: Wheaton College Center for Vocation and Career. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Nicholas Tomas. 2010. After You Believe: Why Christian Character Mattters. New York: HarperColllins Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, Byungyul, Namjun Kim, Changwoo Jeong, Bongje Kim, Youngha Park, Byungsuk Jeong, and Sukhwan Cho. 2012. Systematic Research on Character Education. Seoul: Seoul City Education Research Center Character Education Research Team. [Google Scholar]

- Zait, Adriana, and Paricea Elena Berte. 2011. Methods for testing discriminant validity. Management & Marketing 9: 217–24. [Google Scholar]

| Source | Character Traits | |

|---|---|---|

| Matthew 5:3–10 | humility, empathy, self-control, righteousness, mercy, integrity, forgiveness, justice | |

| Galatians 5:22–23 | love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control | |

| 2 Peter 1:5–7 | faith, goodness, knowledge, self-control, perseverance, godliness, brotherly kindness, love | |

| Handong Global University | wisdom, sexual purity, self-control, love, honesty, integrity, humility | |

| Calvin Virtue | diligence, patience, honesty, courage, charity, creativity, empathy, humility, stewardship, compassion, justice, faith(loyalty + trust), hope, wisdom | |

| Wheaton College | humility, generosity, hardwork, integrity, royalty, broad worldview, trustworthiness | |

| Christian Character Index | joy, inner peace, patience and gentleness, kindness and generosity, faithfulness, self-control, forgiveness, gratitude, compassion, love | |

| C. S. Lewis: Abolition of Man (Lewis 2015) | the law of general beneficence; the law of special beneficence; duties to parents, elders, ancestors; duties to children and posterity; the law of justice; the law of God faith and veracity; the law of mercy; the law of magnanimity | |

| C. S. Lewis: The 12 Narnian Virtues (Pike et al. 2015) | wisdom (including prudence), love (including kindness), fortitude, courage (an aspect of fortitude), self-control, justice, forgiveness, gratitude, humility, integrity (including honesty), hard work, curiosity | |

| Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues (The Church of England Education Office 2015) | civic character virtues | service, citizenship, volunteering |

| moral character virtues | courage, self-discipline, compassion, gratitude, justice, humility, honesty | |

| performance character virtues | resilience, determination, creativity | |

| Items | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Communality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Relationship with Others I—Loving & Caring | ||||||

| 7. I carefully consider and sympathize with what others say. | 0.673 | 0.178 | 0.240 | 0.138 | 0.131 | 0.578 |

| 19. I greet others with a smiling face. | 0.608 | 0.277 | 0.128 | 0.024 | 0.167 | 0.491 |

| 23. I am polite, when talking on the phone, chatting, greeting. | 0.586 | 0.294 | 0.001 | 0.190 | 0.227 | 0.518 |

| 34. I use positive language, which lifts up and encourages others. | 0.577 | 0.209 | 0.260 | 0.222 | 0.247 | 0.554 |

| 36. I show an attitude of caring for others and serving them. | 0.560 | 0.203 | 0.349 | 0.197 | 0.326 | 0.622 |

| 10. I communicate and behave with kindness. | 0.539 | 0.117 | 0.410 | 0.276 | 0.025 | 0.549 |

| 33. I rejoice with those who rejoice and mourn with those who mourn. | 0.490 | 0.282 | 0.218 | 0.168 | 0.396 | 0.552 |

| 13. I seek harmonious communications and decision making within groups. | 0.485 | 0.277 | 0.179 | 0.224 | 0.251 | 0.457 |

| 35. I take the role as a mediator to achieve conflict resolution. | 0.444 | 0.133 | 0.307 | 0.283 | 0.357 | 0.516 |

| 20. I help people who are having difficulties. | 0.433 | 0.304 | 0.362 | 0.126 | 0.364 | 0.560 |

| 18. I take responsibility for my part of group tasks. | 0.430 | 0.329 | −0.028 | 0.254 | 0.353 | 0.482 |

| Factor 2: Relationship with God | ||||||

| 29. I know I am a child of God and believe that God has a purpose for me. | 0.271 | 0.753 | −0.016 | 0.027 | 0.184 | 0.675 |

| 1. I hold hope in God, no matter what the circumstance. | 0.214 | 0.678 | 0.206 | 0.203 | 0.100 | 0.599 |

| 28. I think sexual purity is important and, with God’s help, I maintain it. | 0.174 | 0.663 | 0.023 | 0.073 | 0.138 | 0.495 |

| 27. I endure economic and academic hardships, and difficulties in personal relationships, as I wait patiently for God’s time. | 0.104 | 0.572 | 0.284 | 0.203 | 0.304 | 0.552 |

| 32. I am satisfied with the conditions that God provides for me. | 0.222 | 0.542 | 0.275 | 0.243 | 0.113 | 0.490 |

| 16. I use my time, possessions and talents for the expansion of God’s kingdom in the church. | 0.264 | 0.526 | 0.228 | 0.293 | 0.155 | 0.508 |

| 3. I rely on God’s strength to overcome when I am inclined to sin. | 0.229 | 0.469 | 0.200 | 0.440 | 0.045 | 0.509 |

| 26. I cooperate with all my heart and power for the good works of God. | 0.332 | 0.466 | 0.218 | 0.160 | 0.434 | 0.589 |

| 6. I give thanks in all circumstances. | 0.354 | 0.372 | 0.370 | 0.346 | −0.065 | 0.524 |

| Factor 3: Relationship with Others II—Loving & Peacemaking | ||||||

| 9. I forgive people who have harmed me. | 0.135 | 0.155 | 0.722 | 0.151 | 0.133 | 0.604 |

| 14. I patiently endure people who make things difficult for me. | 0.169 | 0.214 | 0.687 | 0.132 | 0.055 | 0.567 |

| 8. I consider the needs of others before mine. | 0.452 | 0.094 | 0.552 | 0.145 | 0.133 | 0.557 |

| 39. I can put up with discomforts and inconveniences for the benefit of others. | 0.258 | 0.195 | 0.485 | 0.144 | 0.402 | 0.522 |

| 21. I do not quickly condemn others. | 0.211 | −0.010 | 0.477 | 0.419 | 0.200 | 0.488 |

| 11. I help other people without expecting to be thanked. | 0.405 | 0.232 | 0.464 | 0.027 | 0.315 | 0.533 |

| Factor 4: Personal Responsibility | ||||||

| 2. I use time effectively. | 0.218 | 0.129 | 0.060 | 0.726 | 0.102 | 0.605 |

| 4. My thoughts, words, and behaviors coincide. | 0.211 | 0.109 | 0.292 | 0.646 | 0.115 | 0.572 |

| 31. I complete my responsibilities on time, regardless of the situation. | 0.174 | 0.233 | 0.027 | 0.620 | 0.318 | 0.571 |

| 5. I perform the tasks given to me responsibly and sincerely. | 0.431 | 0.213 | −0.010 | 0.588 | 0.197 | 0.615 |

| 15. I am disciplined with my finances. | 0.084 | 0.208 | 0.212 | 0.511 | 0.116 | 0.370 |

| 17. I do not tell a lie, even when there is an advantage to lie. | −0.158 | 0.123 | 0.343 | 0.467 | 0.197 | 0.415 |

| 22. I objectify my anger and express it in a rational way. | 0.151 | 0.071 | 0.421 | 0.425 | 0.270 | 0.458 |

| Factor 5: Social Responsibility | ||||||

| 38. I am interested in political, social, and economic issues, and I agonize over injustice. | 0.257 | 0.073 | −0.006 | 0.211 | 0.650 | 0.538 |

| 25. I believe the church should humbly consider the world’s critique and renovate itself. | 0.131 | 0.212 | 0.073 | 0.048 | 0.622 | 0.457 |

| 12. I am attentive to injustice and participate in reformation. | 0.211 | 0.102 | 0.343 | 0.179 | 0.512 | 0.466 |

| 24. I practice care for the disadvantaged. | 0.335 | 0.093 | 0.267 | 0.235 | 0.495 | 0.492 |

| 37. I know the value of donating my talents and possessions, and practice it. | 0.249 | 0.246 | 0.273 | 0.280 | 0.478 | 0.622 |

| 30. I do not compromise right values, even though this requires me to make sacrifices. | −0.009 | 0.410 | 0.257 | 0.264 | 0.455 | 0.511 |

| % of Variance | 12.58 | 10.94 | 10.14 | 10.02 | 9.32 | |

| Eigenvalues | 14.79 | 1.84 | 1.57 | 1.33 | 1.19 | |

| Models | χ2 | df | SRMR | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||||||

| 39 items | 3020.48 | 692 | 0.056 | 0.870 | 0.861 | 0.056 | 0.060 |

| 29 items | 1663.95 | 367 | 0.042 | 0.906 | 0.896 | 0.057 | 0.063 |

| 28 items | 1529.01 | 340 | 0.042 | 0.911 | 0.901 | 0.056 | 0.062 |

| Threshold | ≤08 | ≥90 | ≥90 | ≤06 | |||

| Construct | Item | Standardized Regression Weight | t-Value (CR) | CR (Construct Reliability) | AVE | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship with Others I: Loving & Caring | 7 | 0.661 | Fix | 0.918 | 0.555 | 0.889 |

| 10 | 0.640 | 18.29 | ||||

| 13 | 0.644 | 18.41 | ||||

| 20 | 0.711 | 20.05 | ||||

| 23 | 0.596 | 17.16 | ||||

| 33 | 0.723 | 20.33 | ||||

| 34 | 0.736 | 20.65 | ||||

| 35 | 0.707 | 19.95 | ||||

| 36 | 0.778 | 21.65 | ||||

| Relationship with God | 1 | 0.710 | Fix | 0.913 | 0.567 | 0.868 |

| 3 | 0.641 | 19.04 | ||||

| 6 | 0.647 | 19.22 | ||||

| 16 | 0.678 | 20.12 | ||||

| 26 | 0.748 | 22.13 | ||||

| 27 | 0.692 | 20.53 | ||||

| 29 | 0.609 | 18.11 | ||||

| 32 | 0.660 | 19.58 | ||||

| Relationship with Others II: Loving & Peacemaking | 8 | 0.691 | Fix | 0.898 | 0.638 | 0.808 |

| 9 | 0.637 | 18.06 | ||||

| 11 | 0.701 | 19.71 | ||||

| 14 | 0.628 | 17.82 | ||||

| 39 | 0.712 | 19.98 | ||||

| Personal Responsibility | 2 | 0.684 | Fix | 0.840 | 0.570 | 0.789 |

| 4 | 0.665 | 18.02 | ||||

| 5 | 0.745 | 19.77 | ||||

| 31 | 0.695 | 18.71 | ||||

| Social Responsibility | 12 | 0.614 | Fix | 0.802 | 0.576 | 0.702 |

| 24 | 0.672 | 17.05 | ||||

| 37 | 0.702 | 17.59 |

| Factors | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | [0.744] | 4.02 | 0.734 | ||||

| Factor 2 | 0.661 ** | [0.752] | 4.02 | 0.786 | |||

| Factor 3 | 0.755 ** | 0.643 ** | [0.799] | 3.77 | 0.864 | ||

| Factor 4 | 0.728 ** | 0.626 ** | 0.627 ** | [0.755] | 3.63 | 0.847 | |

| Factor 5 | 0.729 ** | 0.641 ** | 0.667 ** | 0.647 ** | [0.759] | 3.66 | 0.814 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S. Development and Validation of a Scale for Christian Character Assessment of University Students. Religions 2017, 8, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8050082

Kim S. Development and Validation of a Scale for Christian Character Assessment of University Students. Religions. 2017; 8(5):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8050082

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Sungwon. 2017. "Development and Validation of a Scale for Christian Character Assessment of University Students" Religions 8, no. 5: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8050082

APA StyleKim, S. (2017). Development and Validation of a Scale for Christian Character Assessment of University Students. Religions, 8(5), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8050082