Abstract

This essay is adapted from a plenary talk the author gave at the “Growing Apart: The Implications of Economic Inequality” interdisciplinary conference at Boston College on 9 April 2016, as well as portions of his book Cut Loose: Jobless and Hopeless in an Unfair Economy, a sociological ethnography based on interviews and observations of unemployed autoworkers in Detroit, Michigan, and Windsor, Canada, during and after the Great Recession. The essay discusses four themes from this research. First, it provides a sociological understanding of how long-term unemployment and economic inequality are experienced by today’s less advantaged workers. Second, it illustrates how social policy can improve their circumstances. Third, it examines the limits of policy, and how dealing with inequality also requires changing the broader culture. Fourth, it makes the case for one possible approach to bring about that cultural change: a morality of grace.

Keywords:

unemployment; inequality; morality; grace; blue-collar; white-collar; meritocracy; education; family structure; labor markets 1. Introduction

In this essay, I discuss four themes from my book Cut Loose: Jobless and Hopeless in an Unfair Economy [1]. First, using two of the profiles from my book, I provide a sociological understanding of how long-term unemployment and economic inequality are experienced by today’s less advantaged workers. Second, I describe some of my findings about how social policy can improve their circumstances. Third, I examine the limits of policy, and how dealing with inequality also requires us to change the broader culture. And finally, I make the case for one possible approach to bring about that cultural change—what I call a ‘morality of grace’.

I started my book in the fall of 2008, when the financial crisis struck. It may be hard to remember how frightening that time was, when the economy seemed to be collapsing, and even companies as iconic as General Motors were on the verge of liquidation. At the height of the economic crisis, 15 million Americans were out of work. Four out of ten of these workers went through long-term unemployment—that is, being without a job for more than six months. As for American autoworkers, their industry had just gone through another wave of downsizing, but over the span of the recession the layoffs intensified. Auto industry employment shrank from 1 million jobs to 600,000 [2].

I decided I wanted to go to Detroit and understand what was happening to the men and women who were losing their jobs. The auto industry and autoworkers are central to the American story. This is the industry that helped make America an industrial powerhouse. These are the jobs that helped build a strong middle class in the years after World War II. Employees had powerful unions, high pay, good benefits, job security—even if they did not have a college degree.

Over the last several decades, though, the economy and culture have moved in the exact opposite direction. According to tax data collected by Thomas Piketty and others, the top 10 percent of earners now take in half the country’s income. The wealthiest 10 percent own three-quarters of its wealth. We have not seen this level of inequality since the time of The Great Gatsby [3].

Meanwhile, the middle class is being hollowed out. The nonpartisan Pew Research Center recently reported that the size of the middle class—defined by a consistent income range across generations—has fallen from 61 percent of households in 1971, to 50 percent in 2015 ([4], p. 5). Eight years out of the recession, unemployment is significantly down and there is steady job growth. But millions of Americans continue to be left behind. A quarter of today’s unemployed have been out of work for six months or more—a rate almost as high as what was experienced during the peak of the recession in the 1980s [5]. Many people who want to work aren’t even counted as unemployed because they have given up on finding a job. The labor participation rate—the share of people who are either working or looking for work—is at its lowest level since the 1970s [2]. Since the recession, wages have grown slowly. The typical American family makes less than it did in 1999 ([6], p. 7). Two-thirds of Americans say they are anxious about their financial situation [7], and a majority say they would have a difficult time paying a $1,000 bill from an accident or other unexpected expense [8].

We have come a long way from the well-paid, secure jobs that American autoworkers used to enjoy. To use another auto-related symbol, one could say that our new economic reality is represented, in its most extreme form, by the Uber driver: no benefits, no job security, hustling every day to make a living. But this is not just a problem for blue-collar workers. It’s also a problem for white-collar workers, who are increasingly seeing their good jobs outsourced, automated and contracted away. Today, hospitals send radiology scans to doctors in India to analyze [9]. Lawyers have their document reviews handled by computer programs [10]. As for us, we have to look no farther than our own academic departments: more than half of all faculty now hold part-time appointments [11].

I wanted to understand how these broad economic changes were affecting individuals, families, and communities. Thus, at the tail end of the Great Recession and after, I spent time in Detroit and Windsor, Ontario, which is right across the Detroit River. My goal was to compare how people experienced long-term unemployment in the United States and Canada. I also wanted to compare apples to apples: I looked at the same kinds of workers, working at the same kinds of plants, for the same companies in the same industry. The idea was to focus on the policies and cultures on either side of the border, and examine how and why they made a difference. I ended up doing interviews with former autoworkers at two Chrysler engine plants in Detroit and Trenton, Michigan, and two Ford engine plants in Windsor, Ontario. I also interviewed workers at factories that supply auto parts to GM, Ford, and Chrysler. Thanks to outsourcing, these parts suppliers now employ many more people than the Big Three do, although at lower wages, and with fewer benefits and protections [12].

2. The Impact of Unemployment

What impact did unemployment have on the workers and families I studied? Here is a passage from my book regarding one of the unemployed workers I became acquainted with. The statistics on unemployment and its economic impact are important, but as a sociologist my goal is to get beyond those numbers and provide a sense of its social and personal impact:

John Hope lost his job in 2009. For fourteen years he had worked at a car plant near Detroit, heaving truck bumpers onto the practiced balance of his lean, muscled arms and machine-polishing away the wounds in the rough steel, readying them for immersion in a chemical bath that would gild each piece with a thin layer of luminous chrome. It was a work of magic, conjured up in a foul, fume-drenched cavern, an industrial alchemy that transformed masses of cheap base metals into things of beauty and value.John, fifty-five, excelled at the work. Every day on the job meant handling metal and machinery that could, with a moment’s indecision, crush or maim him. He took pride in the strength required to hold the bumpers without tipping over, and the skill needed to buff each piece precisely, so that every hairline nick or abrasion disappeared, the chemical sheen wrapped perfectly across the smooth steel, and the bumpers arrived at the end of the line looking like lustrous silver jewelry. “If I ain’t doing it good, you’re going to lose the money”, notes John in his Alabama drawl.His Southern roots linger in that whirling, excitable, workingman’s voice, but his job—and the pride, status, and paycheck that came with it—long ago separated him from a personal history of vicious rural poverty. Deserted by young parents when he was just a baby, raised by a grandmother who had to abandon him a decade later when she went blind, John learned to fend for himself. For a time he and his older brother slept in vacant houses and cast-aside cars, on porches and forest floors…[In the seventies,] the lure of Detroit’s auto plants, with their union-won wages, took hold of his imagination. John followed a cousin up there [and] took a job at a plant in Highland Park…For over a decade John saw his income rise steadily…It was enough to support his family of four, enough to buy a red-brick ranch house in the city, enough to give his daughter and son video games, clothes, and other trappings of a middle-class American childhood. It was enough for John to look back and feel pride in what he—an abandoned child, a once-homeless boy, son of the dirt-poor South—had accomplished.Then the Great Recession hit…As America’s automakers fell, the damage spread to the plants that supplied them…His company decided to ship all the work to one of its larger factories, to cut costs. More than a hundred workers at his plant were terminated, John included…Now it is the middle of winter, and John is feeling the loss of income hard…When I visit on a frigid day in January, two stove burners have been left fired up, providing heat. The furnace is shut off because John doesn’t have $1000 to repair it…“You’re used to working, and getting what you want”, he says. “When you’re not working, it’s like being in jail, but you have to get your own food.” He slaps his knee and shrieks with laughter. It is the way he deals with adversity—with a smile and a devil-may-care quip. Ask him how he copes, and he will flash a wide grin. “I feel good. I got a great sense of humor.” Ask him about his job search and he’ll say things will work out. “As long as you believe, you’re going to be all right”, John says…But as the conversation goes on, the certainty starts to unravel, the defensive smiles recede. “I’ll be back to work soon”, he insists—but then adds, after a pause: “It can be stressful.”…The job was more than a job. “To me it’s real bad”, he says slowly, forcing out each syllable, “because the thing about my job—man, it makes me think—my job was like my mother and father to me.” Quietly, John starts to sob. He wipes the tears on the denim collar of his button-down shirt, rubs his eyes gently with his fingers. “It’s all I had, you know”, he goes on. “I worked hard because I had no mother and father. I was cut loose. I hate to think about them…When you growing up young, your mother and father, they take care of you. And I ain’t never had that…All my life I depended on my job as my mother and father. If I could only make it every day, I know I’m all right.”([1], pp. 1–4)

As research has found, long-term unemployment hits people with a psychological blow that is comparable to divorce and the death of a loved one [13,14]. Work is so central to who we are. “What do you do?” is one of the first things we ask someone when we meet them. Work gives us a sense of our importance, of our contribution. It provides a routine, a structure, a deep meaning to our lives.

Let me provide one other example of the emotional toll that unemployment can take—here, not just on individuals, but on entire families. Royce is an American and a former parts worker (all of the names of the respondents quoted in this essay are pseudonyms, per Institutional Review Board requirements). He, his wife and four kids live outside Detroit, in a nice suburban house. When Royce lost his job, he sunk into a depression. “I wasn’t feeling that I was doing my part”, he says ([1], p. 208).

The loss of his breadwinner status also created tensions in his marriage. His wife, Elena, has a job at a property management office. After years of being a stay-at-home mom, she is hungry for success. “I’m…big on my position in the company”, she says. “Because that’s just how I am. Wanting to look good, wanting to feel good” ([1], p. 146). But Elena’s success means she has less patience for Royce’s failures. When they argue, which is often these days, Elena will yell, “This is my house! I pay all the bills! I put all the food in the house!” ([1], p. 118).

And yet, several months after Royce lost his job, Elena ended up losing her job, too. “It’s a lot of emotion dealing with this, and it’s just as hard as the loss of the income”, she says. The family’s finances have become desperate. Their gas was recently shut off. They owe huge amounts of interest on a recent payday loan, and the bill collector keeps knocking. For extra cash, Royce ended up pawning his wedding ring. The fights have gotten worse, too—sometimes, they escalate to the point that Elena starts slapping Royce. “I will try to knock him out, and knock him out the door”, she tells me. During their yelling matches, their five-year-old son cowers in a corner of the living room, crying ([1], p. 119).

3. Policy

Royce and Elena’s story reminds us how wounding and destructive unemployment can be to one’s health and one’s relationships with partners and children. And yet, even in these intimate areas of domestic life, a stronger social safety net can make a difference. In Canada, I found, universal health care and generous job retraining programs made it easier to cope with long-term unemployment. Support for working families, especially single parents with children, went a long way to help the kinds of households usually hit hardest by unemployment. Finally, the government there gave Canadian companies rules of the road so that they could do right by their employees. When every company is required to pay severance, for instance, companies who try to take the high road are not at such a competitive disadvantage.

So, how did these differences in policy play out in concrete terms? Here is one example: Kirsten is an American and a former Chrysler worker. She is divorced and a mother of two young children. During the recession, Kirsten decided to take a buyout and leave Chrysler. In part, it was because her relationship with her fiancé had become abusive. Matters boiled over early one morning, after Kirsten came home right after her Chrysler shift, and her fiancé demanded sex. Kirsten refused. Her fiancé started slapping and strangling her in front of their two young kids. Their son called the police, and her fiancé fled. Kirsten went to work at the engine plant the very next day, with black-and-blue bruises all over her face. Kirsten says she took a Chrysler buyout to get away from that abusive relationship. But she misjudged how tough the job market would be. “I didn’t know that times were so hard”, she says ([1], p. 124).

Unable to find work, Kirsten is now delinquent on her mortgage and credit card payments and considering bankruptcy. She is deeply depressed and recently started taking an antidepressant for the first time in her life. “When I was working at Chrysler, I had nothing like that to worry about”, she says ([1], p. 125).

On the Canadian side of the border, unemployment tended to be less severe for single parents, and stronger policies appeared to play a role in this. Alice is a Canadian and former Ford worker. In many ways she is a mirror image of Kirsten. She, too, is a divorced mother of two. She, too, went through an abusive relationship. At one point, Alice’s alcoholic husband broke her nose and blackened her eyes. The next day, she showed up at the plant. Like Kirsten, Alice couldn’t afford to miss work. Ultimately, the high wages Alice earned at the plant were her ticket out. After she left her husband, she continued to work midnight shifts and raised her two young kids by herself. As I heard often among my women respondents, these good jobs at the plant gave them and their children independence and protection in a sometimes violent world.

Alice took the buyout and left Ford during the recession. Life since then has not been easy. She is deep in debt, with tens of thousands of dollars in personal loans and unpaid credit card balances. But overall, Alice is optimistic. She is attending college to become a nurse, with her tuition fully paid by a provincial retraining program. Even though her unemployment insurance has ended, Alice receives other benefits from the government. She gets a monthly living stipend through her retraining program. She also receives a child tax benefit every month and a sales-tax refund every three months. “It’s going the right way”, she says of her future ([1], p. 142).

4. Limits to Policy

The tough experience of being unemployed in Canada is improved in meaningful ways thanks to these government benefits. That said, enacting good policies is not enough. For one thing, policies that are good on paper aren’t necessarily implemented so well. There are budget shortfalls. There are sluggish and inefficient bureaucracies. The situation has become worse in recent decades. In both America and Canada, in-person services have increasingly been replaced by call centers and websites. Government services have increasingly been outsourced to private firms, or just left underfunded and overburdened.

Take Ken, one of the American parts workers I became acquainted with. His wife left him after he lost his job. Ken has become depressed and he sometimes has thoughts of suicide. He recently started taking antidepressants that a primary care physician gave him. Ken hasn’t been able to see a therapist or psychiatrist and he can’t afford insurance. Ken tried applying for Michigan’s Medicaid program for childless adults—he was told they had no funding left and weren’t accepting new enrollees. So Ken went to the state job center and asked about counseling. He was told there was a two-month wait. “You can commit suicide tomorrow”, he says. Desperate, Ken decided to start going to a church for group therapy. The only sessions available, though, are for Narcotics Anonymous. Ken doesn’t have a drug problem, but he starts attending anyways. “They’ll talk to anybody”, he says. “They’ll let anybody in” ([1], p. 159).

As Ken has learned, governments frequently do not have the funding or staff to fulfill the promises of their social policies. So Ken relies on himself, mowing lawns for cash and hustling every other way he can. “I’m strong”, he says. “I’ll make it. I’ll be alright. I’m not going to let nothing get to me…I’m not ready to check out” ([1], p. 160).

Beyond these problems with implementation, there is another reason we need to go further than a narrow focus on enacting good policies. As important as this work is, it is painfully clear that the hard-hitting measures needed to deal in any long-term way with inequality cannot be sustained in this current political climate. There needs to be a change in the broader culture as well, a culture that ultimately determines what policies are even possible.

This is another reason that I chose to study autoworkers. They represent not just the old economy, but also an older culture of solidarity that we have forsaken. With their strong unions, they championed an all-for-one, one-for-all attitude—one that said, “Let’s lift up everyone at the same time.” In Washington, labor unions like the United Auto Workers led the charge for higher minimum wages, health care, and civil rights. People forget that Walter Reuther, the president of the UAW, literally stood beside Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. while he made the “I Have a Dream” speech during the March on Washington. Back then, a social contract existed between many workers and their employers. Workers toiled away with the expectation that their corporate mothers and fathers would take care of them. Companies made good on those promises, and even big business respected the power of labor. In words that are shocking today, in the 1940s the president of the US Chamber of Commerce, the country’s largest business lobby, said: “Collective bargaining is a part of the democratic process” ([15], p. 21).

As late as the seventies, American CEOs in major companies earned just thirty times more than the average worker, according to the Economic Policy Institute. Huge disparities of pay between executives and workers were seen as unseemly back then. But today, the social norms at top have changed. The gap between CEO and worker pay is about 300–to–1 [16]. Meanwhile, union membership is a third of what it once was [2,5]. Whether you approve or disapprove of unions, it is clear that they have long served as a countervailing power. In the postwar period especially, they checked and balanced the influence of corporations. They promoted pro-worker policies, and perhaps more importantly, they evangelized egalitarian norms throughout society.

With that culture and those institutions in place, it is not surprising that the federal government responded in a robust fashion after the Great Depression to deal with unemployment and support struggling families. But today, in the wake of the Great Recession, political leaders have been less willing to pursue substantial policies to lift up ordinary workers. In fact, across the globe, countries that once provided generously for the unemployed and underemployed have dramatically curtailed their benefits. In Canada, that retrenchment happened during the nineties—under a center-left government [17].

The workers I spoke to were realistic: they knew they could no longer rely on weak institutions to bail them out. Consider Tom, a Canadian and former Ford worker. After his unemployment ran out, Tom went on welfare. But the help the government gives is both insufficient and humiliating, he says. As for unions, they were once important. But “you’re at a point where you have to give something back”, he says. “And now everybody’s saying, ‘The union is doing this, the union is doing that.’ No, they’re not. The company is deciding what they’re gonna do’” ([1], p. 165).

Without anyone or anything to rely on, Tom focuses on schemes to get under-the-table cash. Anything else is a daydream. “When a thousand people band together it makes a difference, but just by myself, no”, he says. “They’re gonna tell me what to do anyhow, so let’s go along with it. Don’t make waves.” But Tom’s inability to turn to institutions means he has no choice but to look to his personal initiative—and his personal failure to seize that initiative. Tom complains about the unfairness of it all, but at the end of the day, when he’s alone with his thoughts in the home he’s about to lose, he is the one he rips into. “I should be able to find employment”, he says. “I couldn’t even get a fucking job at a worm farm” ([1], p. 200).

In the absence of strong unions and interventionist governments, what is left for today’s workers is a go-it-alone perspective of self-reliance—this idea that, “I get an education, I work hard and get the skills I need, and I become successful.” Yet this individualistic viewpoint makes the experience of long-term unemployment all the more wounding. Many of my workers felt like—as they put it—”losers”. And yet being a worthy person in our society is all about being a winner—as some politicians like to remind us.

This culture of winning and losing affected my respondents’ personal relationships in noticeable ways. What I heard among some of the families I interviewed is that people do not care for marrying, or staying with, a so-called loser or a “scrub”. And it goes beyond these working-class households: today, the college-educated marry each other in much greater numbers than in past generations [18]. To a growing extent, as psychologists have found, marriage is about “self-expansion”—about a partner who helps you grow and succeed—and less about loyalty and commitment [19].

This view is part of a broader culture in America, what I call meritocratic morality. This is a belief system that upholds the virtues of self-reliance, willpower, and individualism. The idea of the American Dream captures this viewpoint, though its values have spread throughout the world. According to meritocratic morality, success depends, and should depend, on your own efforts and abilities. This individualistic ideology even seemed to influence some of the autoworkers I interviewed—again, a class that has benefitted enormously from unions and their culture of solidarity.

Paul is a former union steward. Nevertheless, he has a meritocratic, common-sense view of what autoworkers deserve to make. “You got factory workers that didn’t have a fifth-grade education, right, living next door to doctors and lawyers…in $600,000 houses”, he says. “Here’s a guy that says, ‘I’m a doctor and I spent…$100,000 dollars…for an education, for me to get this doctor degree’, and you got a guy that moved out here that can’t speak plain English—he still barbequing on the front porch. You know, it’s like this has got to cease” ([1], p. 214). Blue-collar workers like Paul have internalized the belief that they don’t deserve a very high standard of living. And it’s because they don’t possess the kind of merit that’s now appreciated in this labor market and in this culture.

Of course, there is a fundamental contradiction here. Even as this culture of judgment wins over ordinary workers like Paul, or at least forces them to defend themselves against its criticisms, these same rules of meritocracy don’t apply to the very top levels of the economy. Groups of elite workers—professionals, managers, financial workers—continue to wall themselves off from competition [20]. They still organize collectively, through lobbying, credentialing, licensing and other strategies. But ordinary workers no longer have the same ability to do so, because unions have declined and government steps in less often on their behalf. What we confront in our new economy is what I call a stunted meritocracy. It is meritocracy for you, but not for me.

The obvious answer to this problem would be to enact policies that would bring about equal opportunity—in other words, reform the system to make sure the intelligent and industrious rise to the top. But even if we lived in a society where ability was judged perfectly, in which the rigged rules of this economic game were made fair, a stunted meritocracy would eventually emerge. This is because meritocracy and equal opportunity are distinct concepts. Meritocracy is a system where the talented and hard-working advance. Equal opportunity means that we each have an equal chance at developing those talents and moving up.

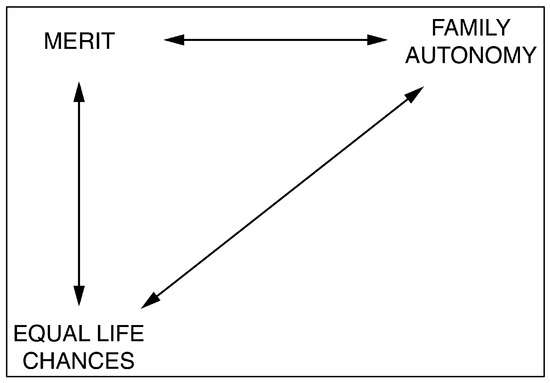

As political scientist James Fishkin has argued, this distinction leads to fundamental tensions in any society that strives to achieve equal opportunity [21]. Fishkin notes that societies distribute wealth and status on three grounds (see Figure 1). According to the principle of merit, qualifications for positions should be evaluated fairly. According to the principle of equal life chances, the likelihood of a child’s later success should not depend on arbitrary traits like gender, race, and family background. And according to the principle of family autonomy, parents should be free to shape their children’s development. The problem, Fishkin argues, is that these three principles are inherently at odds. Choosing any two of them rules out the third. If we want equal life chances for all, we have to prevent parents early on from giving their children a leg up in the meritocratic race, or otherwise impose remedies later in life, such as various forms of redistribution and affirmative action, that will weaken the link between a person’s merit and their reward. If we want meritocracy, we have to find ways to diminish this transmission of advantage from generation to generation, or otherwise accept the fact that opportunities will not be equal.

Figure 1.

According to James Fishkin, when two assumptions about equal opportunity (the principle of merit and equality of life chances) are combined with a third assumption (autonomy of the family), “a pattern of difficult choices emerges”, whereby “commitment to any two of these assumptions rules out the third” ([21], p. 5).

In the real world, access to a good education is drastically unequal. The best predictor of how much education and income you receive is your parents’ education and income. Even at age three, there are large gaps in the test scores of the children of high school graduates and the children of college graduates, and those gaps persist into high school [22]. But Fishkin’s argument is that the inequality we see is more fundamental than this: even in a perfect meritocracy with quality education for all, elite workers can still prepare their children in superior ways.

I want to emphasize that meritocracy has many positive consequences. Its spurs individuals to greater achievement, and countries to greater prosperity. But today, this mentality is being taken too far. While personal responsibility is vital, our economy has become excessively individualistic and unforgiving. It no longer has patience for the notions of loyalty and community that once tempered our relentless pursuit of happiness. A hypercompetitive and status-obsessed culture, in turn, leads to the judgment of less successful people as lazy, uneducated, and incompetent. If they don’t have the markers of merit—education, marketable skills, a good job—then they are less than worthy—as workers, or as marriage partners. As some politicians put it, they are also less-than-worthy citizens—“takers” living off government, rather than “makers” who create jobs, innovate, and make this country great.

For elites, meritocratic morality can take the extreme form of a “greed is good” ideology, one that rejects altruism and slave morality altogether, in favor of the no-holds-barred egoism of the free market, in which self-interest is praised almost as a form of compassion. And yet meritocratic morality is far from just a secular phenomenon. Truly, our modern-day Pharisees can be found in the pulpits and marketplaces alike, judging other people zealously and expecting purity and perfection in all areas. For the unemployed, this perspective contributes to a poisonous self-blame. Sociologist Michael Young, who coined the term “meritocracy”, actually saw it in this negative light: as a social order that would raise up the talented and leave the untalented to blame themselves for their failure [23].

In this sense, meritocracy is a jealous god, bearing manna in one hand and a sword in the other. Those who succeed are praised as men and women of ability and worth, and held up as examples, however anecdotal, that everyone can make it in America. Those who fail are scorned as losers, whose low status is all the more painful because it is deserved.

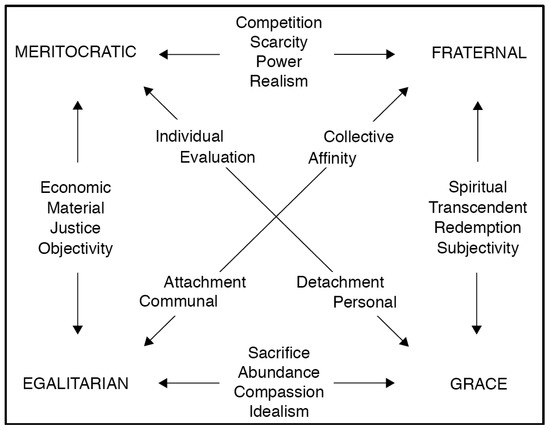

In my book, I define meritocratic morality in opposition to three other kinds of moral thinking about advancement in society and the distribution of economic rewards: egalitarian morality, fraternal morality, and grace morality. As Figure 2 illustrates, I have adapted three of these moral perspectives from the theories of James Fishkin. (Note: wherever words are listed between the four major principles in the diagram below, they identify qualities shared by the two perspectives connected by arrows. For instance, both meritocratic morality and fraternal morality are characterized by competition.)

Figure 2.

The key characteristics of four opposing moral perspectives that determine opportunities and outcomes within society ([1], p. 24).

Egalitarian morality seeks economic justice for the collective. Today’s egalitarians in Europe and North America tend to be more moderate than the ideologues of communism. Rather than equal outcomes, they focus on equal opportunity—a fair shot at the game of life. And yet, just like the proponents of extreme meritocracy, they behold the world with an economic lens focused on each gain or loss.

Fraternal morality is the morality of the tribe. It restrains the behavior of the individual, prioritizing the interests of the collective rather than their own. In return, the individual finds spiritual gain: the transcendent joy and dignity of joining a larger whole. The word fraternal refers to masculine brotherhood, and that is something I want to emphasize, for there is also a dark side to fraternalism: its exclusion, and its chauvinism.

The fourth kind of moral code is what I call the morality of grace. I am not religious, but I take inspiration in the Christian concept of grace—this idea that everyone is saved by God’s grace, not just the deserving. This view has a long tradition in American thought, going back all the way to the Puritans [24]. I feel it best captures the antithesis of the meritocratic ideology. It is a spiritual perspective of nonjudgment and abundance, as opposed to an economic perspective of measurement and scarcity.

In my book, I focus on three reasons that the ideology of meritocratic morality may be growing stronger relative to other moral viewpoints. The first reason is the decline of unions throughout the industrialized world, and the demise of left ideologies that, however flawed they were, provided an alternative language of class consciousness and worker dignity.

Second, the nature of merit has changed, in ways that put blue-collar workers at a disadvantage and debase their self-worth. Before, they could point to the backbreaking work they did on the assembly line to justify their high wages. Hard work still matters—but what my workers called smart work matters more. “It used to be you come up and say, ‘Okay, I’ve got a strong back,’ and all that”, says one of my workers. “Strong back don’t mean shit. You gotta have dedication and you’ve gotta have some kind of smartness, or something” ([1], p. 49). In the modern, postindustrial economy, the focus of merit is more on entrepreneurialism, independence and intelligence, rather than just a strong work ethic. To get a job lower down in the labor market, these sorts of things matter less. And yet the bar of sophistication here is also rising, not just in terms of credentials, but also the presentation of self—the slick résumé, the cheerful personality, the spotless personal record [25].

A third factor bringing about ideological change over time is what I call the new technology of meritocracy. The criteria for judging merit have expanded greatly, thanks to the growing technical capacity to quantify ability and performance [26]. Work today is less about making a living and more about managing a career [27]. At its extreme, it’s about building a personal brand that encompasses all aspects of your life, each one measured and evaluated [28]. And yet the expansion of metrics means the expansion of evidence that proves workers like mine—the less educated, the less advantaged—to be inferior.

5. Grace

I think we need a return to some sort of balance—a healthier and saner way of looking at life. In my book, I make the case for a morality of grace that can complement and deepen our pursuit of egalitarianism. A perspective of grace refuses to divide the world into camps of deserving and undeserving, as those on both the right and left are wont to do. I see it as an antidote to our hypercompetitive and hyperjudgmental society, where we’re always being evaluated and judged: from standardized tests in school, to job performance reviews at work, and especially in the job search, where every mistake we’ve ever made is captured by Google.

Unlike meritocratic morality, grace rejects our obsession with measuring and judging the worth of people, and excusing nothing. But unlike egalitarianism, it also rejects the categories of right and wrong, just and unjust. It offers neither retribution nor restitution, but rather forgiveness.

President Obama gave voice to this idea of grace in his eulogy last year for one of the victims of the Charleston church shooting, the Rev. Clementa Pinckney. In praising the parishioners who welcomed their killer into their Bible study, and the victims’ family members who forgave him in court, Obama invoked grace—the “free and benevolent favor of God”, as he called it—bestowed to the sinful and saintly alike. “Grace is not earned”, he said. “Grace is not merited. It’s not something we deserve” [29].

It is worth emphasizing here that the morality of grace is not synonymous with organized religion, which often loses its way in the pursuit of temporal power. Furthermore, the concept of grace can be seen in many other religions—from Buddhism’s call to accept suffering with equanimity, to the Tao Te Ching’s admonishment to treat the good and bad alike with kindness, to the Upanishad’s focus on the eternal and infinite nature of reality.

We can see the idea of grace in secular writings as well, from the abstract theories of the philosopher Martin Heidegger to the humanism of the astronomer Carl Sagan. Sagan wrote eloquently about these themes in his book Pale Blue Dot, which was inspired by Voyager 1’s photograph of Earth as a tiny blue speck against the vast blackness of space. Amid the competition and cruelty of human civilization, Sagan wrote, this image underscored the “folly of human conceits” and our responsibility to “deal more kindly with one another” [30].

On the most basic level, we see a model for what grace means in our closest personal relationships. If we often choose our friends and lovers based on merit—their intelligence or thoughtfulness or compatibility—with time we come to love their idiosyncrasies and foibles, holding them close just as the boy in the old childhood tale loved his frayed velveteen rabbit.

What does grace have to do with the economy? It helps us recognize that our society possesses enough wealth to provide for all. It allows us to part gladly with our hard-won treasure in order to pull others up, even if those we help are not the most deserving. It gives us the open-mindedness to question whether always being, or hiring, the best and brightest should be our chief goal.

While the unemployed workers I talked to didn’t use the word “grace”, they spoke about it in other ways. A former Ford worker told me he is worried for his kids and their future because the intensity of competition is becoming more and more toxic everywhere in society. “You hear students [say] it’s all right to cheat because…I needed the A to get that job I need”, he says. Being successful in business, too, is about doing “whatever you can do for the bottom line”. And yet he knows there is more to life than this. He wants his kids to learn decency and happiness, things that wealth and fame ultimately cannot provide. Likewise, a union official told me she isn’t sure that anyone—corporate executives, certainly, but her autoworkers as well—really need the life of material comfort and plenty they aspire to have. You can be happy with much less, she points out.

Taking up a perspective of grace is important because the prevailing culture of judgment worsens our society’s growing inequalities. It stands squarely in the way of any serious and sustained effort to deal with the economy’s deep-rooted, structural problems. We dismiss redistribution as “class warfare”, the work of envy and resentment. We fixate on the so-called culture of poverty that prevents people from pulling themselves up, rather than the culture of prosperity that blinds us, the more fortunate, to the hurdles others face. Egalitarian morality finds it difficult to overcome these objections, in part because it, like meritocratic morality, has a fundamentally economic perspective. It measures and judges in the opposite direction—but it measures and judges nonetheless. With a focus on the material and quantifiable, the redistribution of your own wealth is by definition a sacrifice.

Unlike egalitarianism, a morality of grace downplays the importance of material circumstances. Under this perspective, individuals give up their wealth and power—not for the sake of redistribution per se, but because these possessions and positions are not significant when viewed from a broader vantage point. In turn, a morality of grace can open up political possibilities for the sorts of measures that would help middle-class families. It resonates across partisan lines, connecting with the thinking of secular feminist scholars who call for an economy that prioritizes care work, and yet also with the principles of evangelical Christian activists deeply concerned about poverty [31]. In fact, the Rev. David Platt, a prominent evangelical Christian leader, has made one of the most powerful cases for grace, decrying America’s culture of competition, materialism, and single-minded self-improvement. “While the goal of the American dream is to make much of us, the goal of the gospel is to make much of God”, Platt writes ([32], pp. 46–47).

For his part, Pope Francis has not given up on the American Dream—but he has recast it. As he suggested in his 2015 address to Congress, the American Dream is not about materialist excess, but spiritual striving [33]. It is not about success, but fulfillment. In his apostolic exhortation a year later, Pope Francis also spoke to the idea of grace, calling for the Church to be more welcoming and less judgmental toward those who stray from doctrine [34].

In fact, a morality of grace is most needed not among the poor, but among the powerful—those who judge from up high, secluded in their literal and figurative gated communities. A genuine commitment to this viewpoint makes the rich more tolerant of taxes to pay for social programs, for example. It gives corporate leaders greater respect for workers’ rights and government regulations, measures they fiercely resist when they see profit as their sole aim. The presence of these sorts of policies, in turn, creates new social norms about what is, and what is not, acceptable behavior. As for the economy’s discouraged and desperate, taking up a perspective of grace means more in the way of solace, self-worth, and perhaps even employment, as society recognizes that economic efficiency is not the end but the means to a fulfilled life [35]. Social movements must take the lead, as they did in previous historical periods, to inspire the public and bring about this cultural change—and policies that make labor organizing and other forms of grassroots activism easier, and reduce the influence of money in politics, will make it more likely they will succeed.

In other words, there can be a virtuous circle at work here. Strong policies can help bring about a perspective of grace. If you don’t have to scramble to undercut your corporate competitors—if you don’t have to struggle to survive on low wages—you can think about the big picture. And grace, in turn, can make these policies more possible and sustainable. When we are not obsessed with comparing ourselves with others, when we are not intent on blaming others for their failures, we can deal more kindly with one another. We can deal more kindly with ourselves. Grace is a forgiving God.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the research and writing described in this essay was provided by the National Science Foundation, the American Sociological Association, the Harvard Joblessness and Urban Poverty Research Program, the Harvard Multidisciplinary Program in Inequality and Social Policy, the Harvard Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, the Berkeley Center for Culture, Organizations, and Politics, the Berkeley Canadian Studies Program, and Virginia Commonwealth University’s College of Humanities and Sciences. I would also like to thank the two anonymous peer reviewers for their thoughtful and helpful feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Victor Tan Chen. Cut Loose: Jobless and Hopeless in an Unfair Economy. Oakland: University of California Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- “US Bureau of Labor Statistics. ” Available online: www.bls.gov (accessed on 30 October 2016).

- Thomas Piketty. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. The American Middle Class Is Losing Ground. Washington: Pew Research Center, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Victor Tan Chen. “Charts and Data.” Available online: https://victortanchen.com/charts-and-data (accessed on 30 October 2016).

- Bernadette D. Proctor, Jessica L. Semega, and Melissa A. Kollar. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2015; US Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60-256(RV); Washington: US Government Printing Office, 2016.

- Dave Shaw. “The Economy’s Improving, But Americans’ Economic Anxiety Persists.” Marketplace. 14 March 2016. Available online: http://www.marketplace.org/2016/03/11/economy/anxiety-index/economys-improving-americans-economic-anxiety-persists (accessed on 13 March 2017).

- Kimberly Adams. “Where to Turn When There’s Nowhere to Turn.” Marketplace. 17 March 2016. Available online: http://www.marketplace.org/2016/03/16/your-money/anxiety-index/where-turn-when-theres-nowhere-turn (accessed on 13 March 2017).

- Andrew Pollack. “Who’s Reading Your X-ray.” New York Times. 16 November 2003. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2003/11/16/business/who-s-reading-your-x-ray.html (accessed on 13 March 2017).

- John Markoff. “Armies of Expensive Lawyers, Replaced by Cheaper Software.” New York Times. 4 March 2011. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/05/science/05legal.html (accessed on 13 March 2017).

- John W. Curtis. Trends in Faculty Employment Status, 1975–2011. Washington: American Association of University Professors, 2013, Available online: https://www.aaup.org/sites/default/files/FacultyTrends.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2017).

- Center for Automotive Research. Contribution of the Automotive Industry to the Economies of All Fifty States and the United States. Ann Arbor: Center for Automotive Research, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Richard E. Lucas, Andrew E. Clark, Yannis Georgellis, and Ed Diener. “Unemployment Alters the Set Point for Life Satisfaction.” Psychological Science 15 (2004): 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard E. Lucas. “Time Does Not Heal All Wounds: A Longitudinal Study of Reaction and Adaptation to Divorce.” Psychological Science 16 (2005): 945–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank Levy, and Peter Temin. Inequality and Institutions in 20th Century America. Working Paper No. 13106; Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence Mishel, and Alyssa Davis. CEO Pay Continues to Rise as Typical Workers Are Paid Less. Issue Brief #380; Washington: Economic Policy Institute, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Keith Banting, and John Myles, eds. Inequality and the Fading of Redistributive Politics. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2013.

- Andrew J. Cherlin. Labor’s Love Lost: The Rise and Fall of the Working-Class Family in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur Aron, Tracy McLaughlin-Volpe, Debra Mashek, Gary Lewandowski, Stephen C. Wright, and Elaine N. Aron. “Including Others in the Self.” European Review of Social Psychology 15 (2004): 101–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob S. Hacker, and Paul Pierson. Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer—And Turned Its Back on the Middle Class. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- James S. Fishkin. Justice, Equal Opportunity, and the Family. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- James J. Heckman. The American Family in Black and White: A Post-Racial Strategy for Improving Skills to Promote Equality. Discussion Paper No. 5495; Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Young. The Rise of the Meritocracy. New Brunswick: Transaction, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alan Heimert, and Andrew Delbanco, eds. The Puritans in America: A Narrative Anthology. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985.

- Ofer Sharone. Flawed System/Flawed Self: Job Searching and Unemployment Experiences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Victor Tan Chen. “Living in an Extreme Meritocracy Is Exhausting.” The Atlantic. 26 October 2016. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/10/extreme-meritocracy/505358 (accessed on 13 March 2017).

- Carrie M. Lane. A Company of One: Insecurity, Independence, and the New World of White-Collar Unemployment. Ithaca: ILR Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Steven P. Vallas, and Emily R. Cummins. “Personal Branding and Identity Norms in the Popular Business Press: Enterprise Culture in an Age of Precarity.” Organization Studies 36 (2015): 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barack Obama. “Remarks by the President in Eulogy for the Honorable Reverend Clementa Pinckney.” 26 June 2015. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/06/26/remarks-president-eulogy-honorable-reverend-clementa-pinckney (accessed on 13 March 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Carl Sagan. Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space. New York: Random House, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sabine O’Hara. “Everything Needs Care: Toward a Contexts-Based Economy.” In Counting on Marilyn Waring: New Advances in Feminist Economics. Edited by Margunn Bjørnholt and Alisa McKay. Bradford: Demeter Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- David Platt. Radical: Taking Back Your Faith from the American Dream. Colorado Springs: Multnomah, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jorge Mario Bergoglio. “Address of the Holy Father.” 24 September 2015. Available online: https://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/speeches/2015/september/documents/papa-francesco_20150924_usa-us-congress.html (accessed on 13 March 2017).

- Jorge Mario Bergoglio. “Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Amoris Lætitia of the Holy Father Francis.” 2016. Available online: https://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_exhortations/documents/papa-francesco_esortazione-ap_20160319_amoris-laetitia.html (accessed on 13 March 2017).

- Victor Tan Chen. “The Spiritual Crisis of the Modern Economy.” The Atlantic. 21 December 2016. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/1857/11/spiritual-crisis-modern-economy/511067 (accessed on 13 March 2017).

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).