Teresa de Jesús’s life was exceptional, in both senses of the word. In a period where women were generally excluded from participation in public life, she managed to initiate one of the most important religious reform movements in early modern Spain, to found seventeen convents, and to achieve support from the highest Church authorities for her visionary practice and her written works.

1 The exceptionality of Teresa’s life is inseparable from her exceptional

Libro de la vida (

De Jesús 2004a), which could be considered the first autobiography.

2 Many women across Spain and Spanish America sought to imitate aspects of Teresa’s life, both her activities as a reformer and convent founder and her interior spiritual practices. The

Libro de la vida itself contains a guide for a life of interior prayer; the very purpose of this section at least, was to promote the imitation of its author’s spiritual practices. However, what it could not anticipate was the degree to which early modern spiritual women (and men, although in lesser numbers) included the act of life-writing itself in their imitation of Teresa’s life.

The impulse to imitate Teresa in this respect did not come entirely from the writers themselves; confessors imitated her confessors Pedro Ibáñez and later García de Toledo’s act of obligating their spiritually gifted penitents to write an account of their spiritual experiences. In Chapter 5 of the First Part of

Don Quijote (

Cervantes 1605), Miguel de Cervantes poked fun at the sudden proliferation of imitative sequels of

Amadís and other books of chivalry, but the chivalric trend pales in comparison with the effect produced by Teresa’s

Vida among practitioners of spiritual prayer over the next century. Over the next hundred years, it would seem that every literate woman in Spain with an inner prayer life wrote out some account of her visions, raptures, or temptations. For the remainder of this article I will use the term

vida espiritual to refer to the popular trend, distinguishing it from isolated examples of first-person visionary writing from the medieval period. This is no way denies the influence, direct and indirect, of medieval women mystics on the Spanish writers. Catherine of Siena’s visions in particular were an undeniable influence on Spanish mystical

experience, but none of the early modern Spanish cases I consulted mention Catherine of Siena, Angela Foligno, Hildegard of Bingen et al. as direct influences as

writers. If we look at the chronology of

vidas produced in Spain, Teresa is undeniably the initiator of the trend and the model followed by all of her successors. Spanish visionary writers mention Teresa constantly: reading her works, following her example, seeing her in the visions themselves. As striking as the resemblances are with some earlier texts, the contrast between the almost total absence of any mention of these predecessors in these

vidas versus the omnipresence of Teresa and her writing is even more so.

It is impossible to know how many early modern women wrote some form of a

vida espiritual. A censor of one such text commented, as an aside, that “It is so common among little women, secular and religious, to write their lives, and say that they experienced ecstasy, that is it seems to be catching on like a pernicious sect.”

3 Isabelle Poutrin’s

Le voile et la plume is the first systematic catalog of the genre; counting only those written in Spain, she arrived at a total of 113. In 2007, Fernando Durán López amplified her research and added an additional 48, mostly lost or incomplete. He also includes a “handful” of

vidas from Spanish America, while recognizing that he did not pretend to offer any sort of a complete panorama. However, we must assume that the actual number of

vidas—if we interpret the term broadly to include any first-person written account of spiritual experiences, partial or complete—was far, far greater. These were texts almost destined to disappear; there are so many reasons a

vida might have been lost that it is a wonder any survived at all. In general, the institutional exigencies that produced the genre to begin with determined which

vidas were preserved.

4 The

vidas served an initial purpose of assisting a confessor in judging the spiritual progress of his penitent; after these judgments were made, it was often deemed advisable to burn the accounts rather than provide evidence for a possible investigation instigated by hostile clergy. Indeed, almost all of the extant

vidas, and many Inquisition trials of

alumbradas, refer to other papers that were lost or destroyed.

Vidas could be destroyed as an act of censure, an act of protection from other hostile authorities, or simply for expediency. If we leave aside those

vidas seized in Inquisition cases, spiritual autobiographies were only preserved when they were deemed to serve a second function, as documents attesting to an

exemplary life. Those

vidas selected for preservation and publication were usually subjected to additional editing, further pushing the texts into conformity with a model and further obscuring the variety and complexity of the genre itself.

Historians have long studied letters, petitions, depositions et al. as evidence of changes in social relations and subjectivities, but autobiography has traditionally been considered a “literary” genre and the selection criteria for literature have prevailed in limiting the examples studied. Even in the last thirty years, in which crucial work has been done to place Teresa in a context of spiritually innovative, writing nuns, the focus has been on her “mothers” and “sisters” who led spiritually accomplished lives and/or wrote literarily accomplished works.

5 Following on Schlau and Arenal’s ground-breaking anthology (

Arenal and Schlau 1989), there have in recent years been numerous critical editions of a broader circle of early modern European

vida authors, including several Spanish authors.

6,7 Because these editions tend to come from feminist scholarship, there is a tendency to select women who imitate Teresa’s model of resistance through the sophisticated appropriation of the language of humility, and in the case of women who were in fact condemned, there is a tendency to read these women as martyrs. Yet, as I will show, the representation of these women as Teresan in their capacity to articulate a spiritual self requires a level of editing that is not, in the end, all that dissimilar from that which was performed by the women’s contemporaries and co-religious when they adapted the

vidas to serve as hagiographic examples. When we compare original manuscripts against their treatment in contemporary editions or integrated into historical accounts, we often see a similar impulse to impose coherence and clarity on some fairly disorderly texts. This is accentuated by the editor’s natural impulse to make texts legible: to, in a word, edit. If we are solely interested in these works for the spiritual practices they describe, the editing makes sense and would seem to have little material effect on the conclusions we draw, but if we are interested—as I believe we should be—in the way that writing reflects and shapes subjectivities, then the signifiers matter and we cannot sacrifice them in the name of the signified.

As I have noted, the extant corpus of

vidas is probably only a fraction of the entire production, but we cannot work with texts that no longer exist, and in the limited space of an article, it is even impossible to work with more than a representative fraction of the extant corpus at once. In the following pages, I wish to show through a few examples how expanding the canon might change our understanding of the genre of the

vida and its limits, and what the less successful

vidas (sucess here being measured in terms of institutional approval and promotion) suggest about the limits and possibilities of writing itself as a vehicle for the expression and formation of female religious subjectivity in the period.

8 I will examine works at diverse points on this continuum, beginning with a

vida which was published in a modern edited volume and whose author did achieve recognition in her lifetime. María Ángela Astorch (1592–1665) was a Catalan nun, abbess, and founder of two Capuchin convents (in Zaragoza and Murcia). The process for her beatification began shortly after her death and further steps were taken at various times throughout the eighteenth century, although the official beatification did not occur until 1982. She wrote of her spiritual experiences from an early age, and yet her writings were not published until 1985. It is this “intermediate” state of spiritual fame—sufficient to allow her writings to survive, but insufficient to motivate a complete reworking into hagiography—that allows us to see or at least intuit all of the messy, multiple, and heterogeneous threads that went into composing the tapestry of a spiritual life. Because Lázaro Iriarte, the editor, obeys the dictates of academic rather than hagiographic scholarship, he preserves at least some of the traces of an original diachronic progression of spiritual papers produced over decades. They give us further insight into the way that writing mediated self-knowledge, self-presentation, discernment, and projection of authority in an early modern convent.

The bulk of the

Camino interior, as Iriarte titles the collection of Astorch’s works, consists of a chronological diary of spiritual experiences from 1606 (when she would have been 14 years old) through to 1651. The apparent continuity of an entire life recounted as a series of spiritual events belies not just the heterogeneity of the entries but also the relation between the author and the life recounted. The entries up through 1626 chronicle a spiritual life lived only against a Church calendar; there are no dates or years, only liturgical seasons and hours. Beginning in 1626, however, the accounts are separated by year. What might seem an incidental detail is in fact essential in understanding the role that writing played in Mother Astorch’s life. As Iriarte explains, drawing on Astorch’s own account, “María Ángela was accustomed, from childhood, to communicate, in writing, her spiritual experiences with her confessor” (

Iriarte 1985, p. 81). Her first confessor used these accounts to judge her spiritual progress. However, these are not the accounts we are reading in

El camino, because, “having informed him—she says—she would immediately tear up or burn the papers” (ibid.). Later, when she had gained certain renown and ascended to a position of authority in a new convent, she continued to destroy the

relaciones “once they had served their purpose” but some of her readers began to save her accounts, and as Astorch herself records, she also “went along saving a decent amount, although without any order, in drafts, on the blank space of letters, and in such a way that only I could understand” (ibid.). It is only once she was elected abbess, in 1626, that her confessor, Father Arbués, asked her to save all her accounts, and “he ordered her to put them in order and fill in those that were missing.” Father Arbués, along with his confessor, to whom he had turned over many of the letters and notes, worked to create order out of the diverse material. From 1626 to 1642, the entries are periodic, but identified chronologically, although Astorch herself tells us they too were subject to retrospective editing:

In this year of 1642 my confessors and spiritual fathers, having first read my papers that touch on matters of my conscience and spirit, have ordered me to go back and write what I have written from 1622 to the present year of 1642. The reason is that I wrote without the slightest order or structure and many drafts were on loose and damaged paper, and even between the lines or in the blank spaces of letters.

Finally, in 1651, “she managed to gather everything” in a single manuscript, “to which she added the most recent accounts, up to 1656” (

Iriarte 1985, p. 82). Thus, the

Camino interior is a

vida produced over the entirety of Astorch’s

vida, but not conceived of as a single coherent work until relatively late in the author’s life. We can see here the diachronic process through which a

vida passed from one function to another: from a series of discrete steps to be monitored to a single “camino” to be imitated.

The diverse circumstances of production translate into a heterogeneity of textual forms. Although Astorch first explains in her own voice the chronology of the mandate to write and the reason she is going back to reconstruct her early years, the narrative does not start immediately with an account of those years but instead as a dialogue in which she recreates a conversation with father Bartolomé de Jesús of the discalced Carmelites, regarding “certain doubts and temptations and inner callings” (

Astorch 1985, p. 93). She writes his counsel and general approval of her mystic practice, based on a reading of her papers (the very papers she is, we imagine, re-creating in this section of the narrative). The re-created conversation alludes constantly to other papers (“Now I begin to write and to reveal the obscurity of my loose papers. And first of all, it can be taken for granted that it was a miracle if I recorded the year, month, or day, and my confessors never called my attention to this”) (

Astorch 1985, p. 99) and to the past history of writing that has enabled her to arrive to the point where she is authorized to write this past history of her writing.

When we arrive at 1642, the chronological accounts of spiritual mercies give way again to dialogue, but this time it is not a recreation but instead the insertion of the epistolary exchanges between Mother Astorch and the future Inquisitor Alejo de Boxadós, who would eventually be the one to order the editing of the work into the single

camino we are reading. Unlike the recreated voice of Father Bartolomé, here the real questions and follow-ups of her interlocutor mostly can only be intuited from Mother Astorch’s side of the exchanges, although she does occasionally repeat a question in her answer. (e.g., Answers to the questions to which Your Reverence orders me to respond: Question number 1: Your Reverence asks what other pains I have, so we may know if they stem from the same burning in my heart....I respond that it is from the same burning in my heart...(

Astorch 1985, p. 280)). Eventually the examination gives way to a more open-ended exchange of thoughts and experiences, covering everything from scriptural interpretation to issues in the convent. There is no culmination or triumphal climax; instead, the exchanges end and Iriarte opens another section which he titles “Accounts of daydreams with spiritual significance” and then another called “Minor spiritual writings.” These are a heterogeneous mix of devotional activities, daily meditation exercises, and exegetic writings. In several of the sections, Astorch narrates her own spiritual exercises, in a first-person narration that is inseparable from the voice of the chronological portion of the collection. It seems that Iriarte has separated these “minor works” from the “camino” based on the model of Teresa de Ávila, and the separation of her

Libro de la vida from the

Castillo Interior and the

Libro de las fundaciones. However, the majority of early women

vida writers, at least those who held a position of authority in their convents, did not clearly compartmentalize their self-writing from more practical or prescriptive spiritual writing, and indeed Teresa’s own

Libro de la vida contains a manual for spiritual oration. If such separations were drawn, it was by posthumous hagiographers who re-shaped the raw materials of self-narrative into a narrated, model self.

The raw materials we find in conventual and Inquisition archives testify to a lifelong process of spiritual self-narration that could take many forms: poetry, prayer manual, diary, letter, and even drawing. Nuns and

beatas wrote in in notebooks, on the back of other documents or letters, in the margins or blank spaces of other books. They wrote and they encouraged each other to write. The remaining examples I wish to look at come from texts that were never edited, and that seem to have survived mostly by accident. Luisa de Ascención (Luisa de Carrión)

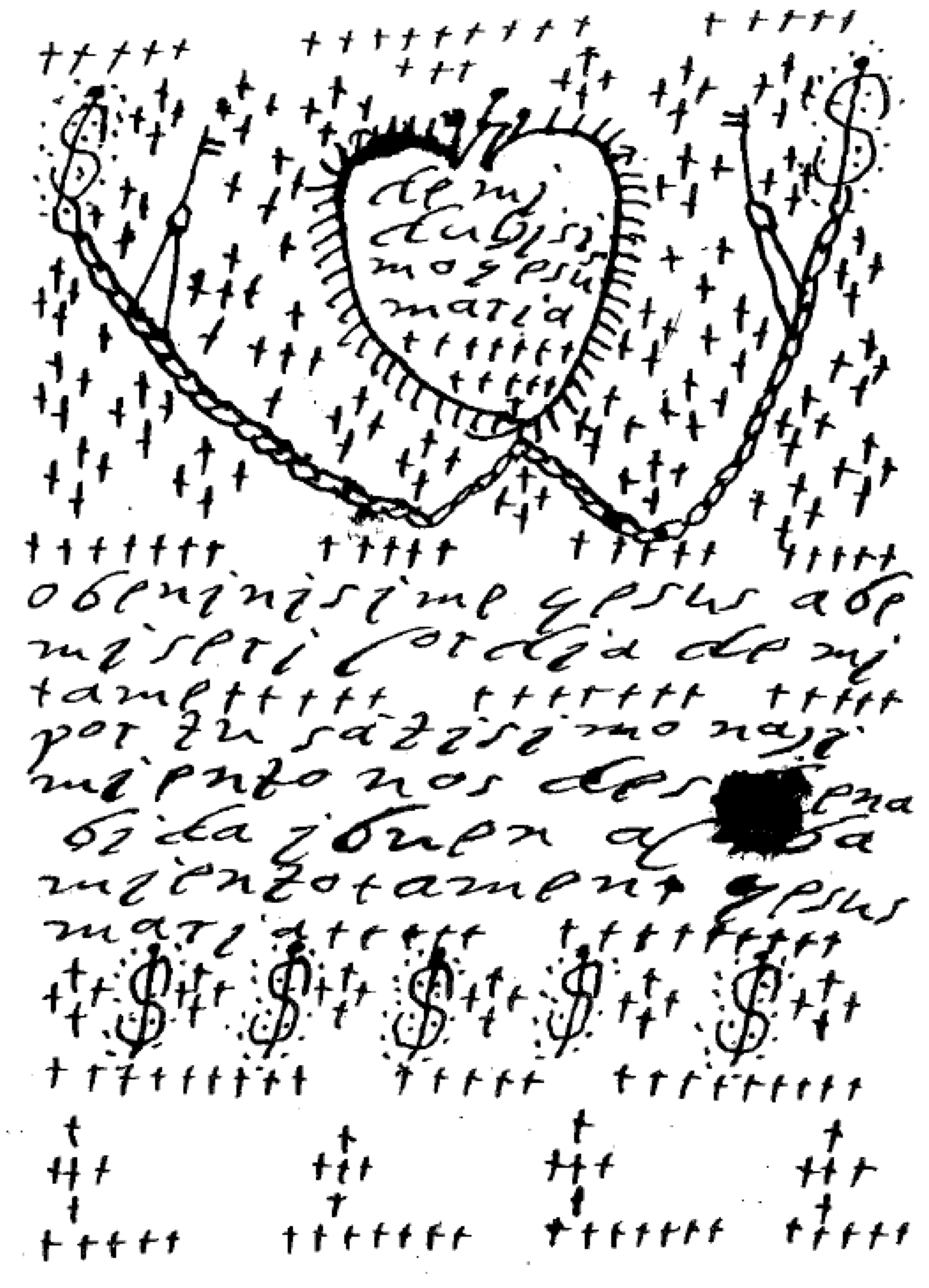

9 developed her own coded system of crosses and hearts with which she filled the margins of the thousands of letters she wrote.

10 She also filled in the blank pages of books such as this one, found in the Membership Book of the Brotherhood of the Purification (

Libro de Firmas de la Hermandad de la Purificación).

11 (

Figure 1).

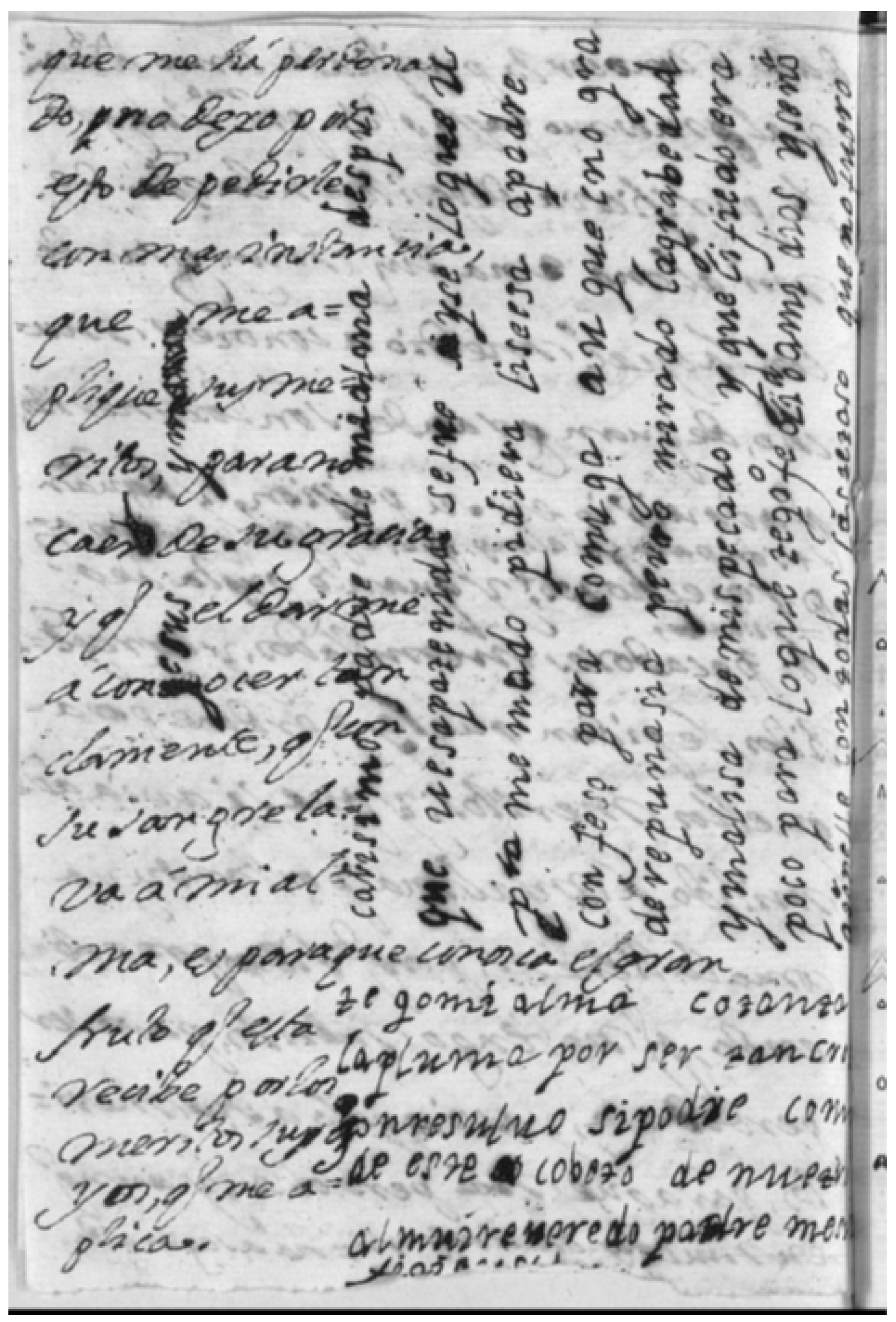

Her life was a constant production of words and signs, the overflow of writing echoing the overflow of spiritual devotion to which it attests. A similar, although more disturbed, example of narrative overflow can be found in the writings of María de Ortola, a Valencian nun of humble origins who became librarian of her Dominican convent around 1720 (

Poutrin 1995, p. 310). Her frequent experiences of possession and rapture prompted her confessor to order her to write out her life, a command she fulfilled with sixty notebooks of obsessive writing. The judgments of the convent authorities were mixed, with some calling for her expulsion and others approving her spiritual gifts and encouraging her writing. She was investigated twice by the Inquisition and eventually condemned for imposture and sentenced to perpetual reclusion. The 476 folio manuscript saved in the

proceso12 provides a fascinating example of a

vida coming apart. The account begins as a legible narrative account of spiritual union and torment, but midway, Ortola begins to write in different directions on each page, writing over previous writing and impeding legibility (

Figure 2).

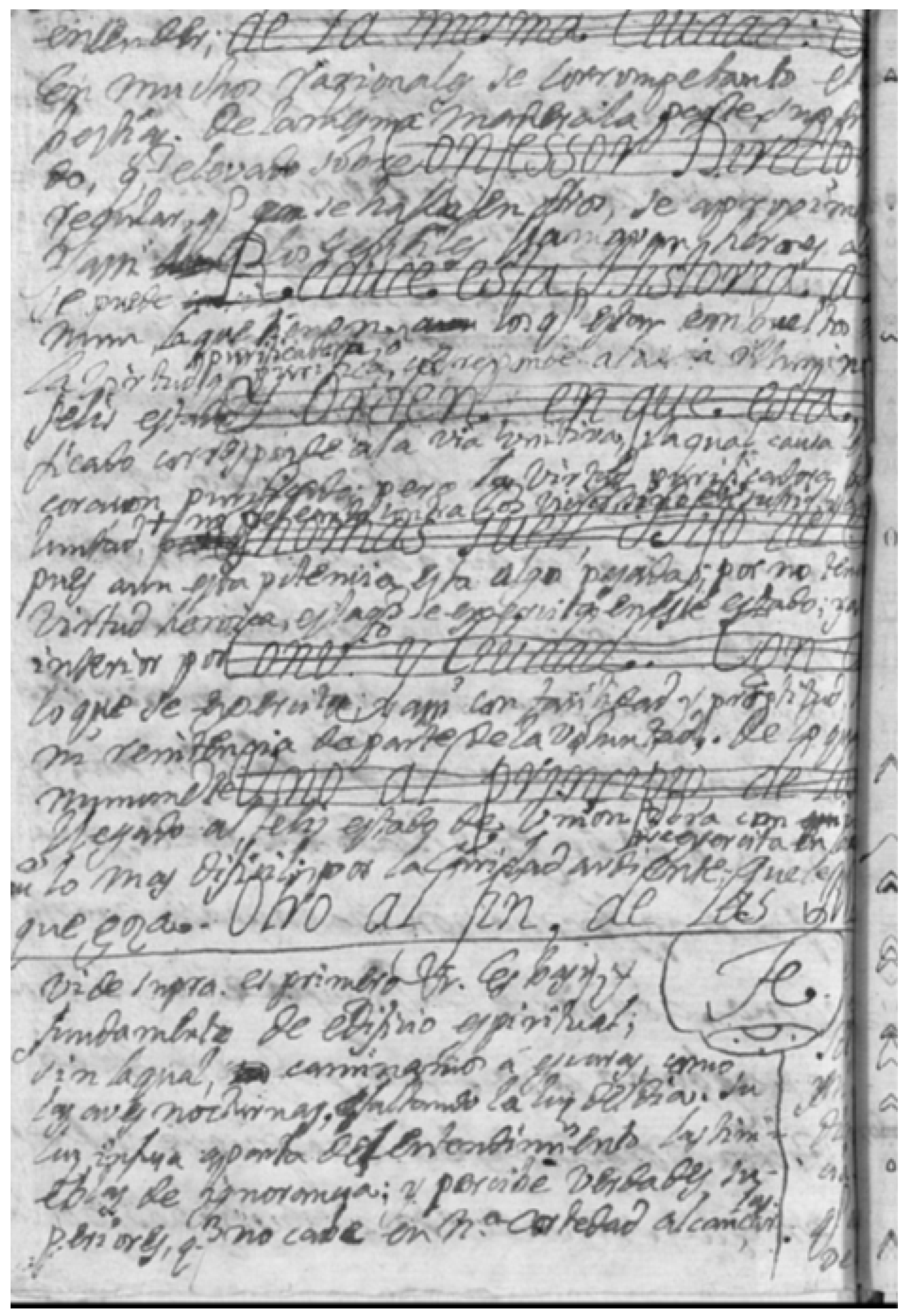

Her spiritual experiences are increasingly tales of illness and possession, and the breakdown in the narrative seems to accompany the increasing torments she narrates. In parts she seems to be writing, or perhaps writing over, musical staff notations (

Figure 3).

Other pages have inexplicable grid lines and on some of the folios, inserted seemingly arbitrarily but by the end dominating the “narrative”, she has written under the heading “Regula” a series of Biblical citations in Latin regarding raptures and prophesy. Is this an attempt to self-exorcise or self-discern? Is she writing while possessed? A close textual study of the manuscript is beyond the scope of this article, and the

proceso itself does not contain a

calificación13 of the writing. We cannot judge how the Inquisitors interpreted the

vida in relation to other evidence, since the Valencia tribunal’s papers do not include complete

proceso transcripts, although the summary of witness statements suggests that the harsh sentence was based on sexual transgressions and violation of convent rules, rather than a judgment of the seized

vida.

14We have much more information about how Inquisitors read a disordered

vida in the case of María Bautista, a

beata in Madrid who wrote a

vida while in prison, as a self-defense in the face of Inquisition accusations of feigned sanctity and

alumbradismo. As Andrew Keitt notes in his study of the case, María Bautista saw this self-narrative as “part of a larger autobiographical project...the notebooks conserved within the trial transcript, then, appear to comprise a wide range of prior autobiographical activity consolidated and redeployed into a series of texts that functioned as a spiritual chronicle and a legal defense combined” (

Keitt 2003, p. 115). In an

audiencia Bautista called during her trial, she reported that, in addition to the notebooks written in prison, “she has written the discourse of her life and the purest occurrences in her spirit and she delivered it to Father Pedro de Tapia...and in addition to these accounts she has also sent other papers to Alcalá....and that Father Francisco Soria, her confessor, also has papers of hers although in the past six months he has torn some of these that he had saying that all her things [her spiritual experiences] were good” (fol. 121r).

15 She also refers repeatedly within the extant

vida to her other writings, which include accounts of her spiritual experience (a “notebook of my soul”), papers exchanged with diverse spiritual advisors, and even unsolicited letters to el Conde Duque de Olivares and the Inquisitor Adán de la Parra prior to her arrest. As Keitt notes, it was not unprecedented for women of humble status to offer spiritual direction to the king, and both Felipe IV and Olivares were known to correspond with nuns who counseled them based on visions. Bautista, however, is not a nun, and despite her attempts, she has no support from intermediaries with access to the palace. Whereas Felipe IV consulted nuns with a reputation for sanctity, according to Bautista’s prison

vida, the appeal to Olivares and Parra marked the beginning of her spiritual journey. Her imitation of hagiographic models consisted of copying the most visible and spectacular

ends, without much thought for imitation of the means through which such ends were achieved. Her writing repeats the problems that plagued her project itself: it jumps from Teresan benchmark to Teresan benchmark (ecstatic vision, demonic torment) without continuity or structure.

Keitt reads Bautista’s self-narration for multiple readers as part of a conscious and sophisticated strategy on Bautista’s part to “exploit divisions within the ranks of her superiors” (129) and as a sign of her agency and autonomy. Through selective quotes and a substantial editorial intervention in the translation

16—he recreates a writer who is an astute and sophisticated imitator of Teresa’s rhetorical strategies, and who, like Teresa “manipulates” official discourses “for her own ends” (118). Yet if we look at the original notebooks, we get a different sense: a woman who is

unable to assert agency or autonomy in her life precisely because she cannot structure her

vida. Her failure to control her narrative, the textual disorder that makes her

vida nearly incoherent, suggests that the failure as a narrator is inseparable from her failure to found an order or achieve legitimacy.

The greatest difficulty the reader of the notebooks encounters is the lack of chronology or spiritual arc. Where Teresa’s vida narrates not just a life journey but also a clearly delineated spiritual progression, Bautista’s narrative, after the briefest profession of humility and submission, jumps immediately to narrating a divine confirmation of her sanctity. There is no discussion of method, of a process of recollection, much less a progression in the results. She jumps from past to present, from mystic visions to squabbles with other beatas, from protestations of abjection to declarations of sanctity, without indication of a self that accompanies or reflects on these transitions. Precisely because the imitation fails less in its ability to hit individual notes than in the lack of any melody, one can only get a sense of the disorder through extended citation.

By the third notebook, she writes almost as if in a stream-of-consciousness:

17Our Lord knows I have never meant to deceive or be deceived by the Devil. My lady the unblemished dove protects me from his claws, prays for me and my spiritual fathers and thus I fear no deceit, nor can the Devil even if he claims the trump cards in this game because God became man from his pure heart and he who seeks him with purity of intention and seeks the mother and son in my opinion truly raises his soul with this game and all the trump cards and the Devil loses his wager when he pretended to swallow the bone that in times past he split with his teeth. For his great confusion I have written in some places that my confessors have, finally he does not know what has happened with this exceptional sinner for this I shall endure much suffering in this life and the next. Here I ask for strength to confound the Inferno, suffering constantly, no matter how much the demons and creatures and my incomparable weakness overtake me, I am on the cross with Him...

I am persecuted by all and I bear this cross all my life. I have received spiritual knowledge regarding certain things when I do not wish for consolation in anything. Our Lord does not at all wish to bear my sorrows, enlightening me. I am prostrating myself at his feet without abandoning my confessor because it is the appropriate way to pray. Father Vega will convey my things and I will be commanded to do what I must in my extraordinary journey. One father will not suffice because my spirit is indifferent like writing is in different ways to my things and much light is needed to understand them.

(Bautista 1639, fol. 56v–59v)

A few lines down María writes that “my confessor has always been of the opinion he says I am crazy, and just as it might occur to me to talk about something else I have taken to talking about spirituality” and the Inquisitor has written in the margin, “this is true” (fol. 60v). The calificadores who analyzed María’s notebooks were generally of the same opinion; they found little to condemn as heretical and some applauded her piety and willingness to suffer, but they generally concurred in that she was crazy, ignorant, and overly suggestible, a poor reader and worse imitator of Teresa’s life and writing. The censuras emphasize the lack of order to the manuscript: “the second thing that these papers contain are visions, prophecies, and favors from Our Father....and I cannot make head or tails out of them as she states them. They show neither connection, gravity, prudence, nor even credulity.” (fol. 69r). Another calificador wrote “I will not list at length the idiocies, deliria, nonsense, silliness, and frivolity that is found in these papers...As much as she tries to disguise her madness, it is my judgment that these papers do not contain anything that concerns the Holy Office” (fol. 10r). The Tribunal itself followed this recommendation, absolving Bautista of wrongdoing but specifying that she confess exclusively with Padre Soria, a confessor who had previously been unsympathetic to her spiritual pretensions and had repeatedly advised her to burn her writings. It is an ambiguous sentence, to be sure; on the one hand, Bautista escapes explicit punishment, but one senses that the negation of her self-authorship equated a negation of her very self. Her lifelong autobiographical project was her means of self-fashioning, and the denial and destruction of her writings meant a rejection of her legitimacy as a subject. We cannot say whether her earlier writings were clearer or “better” imitations of Teresa’s Vida, whether the disorder that plagues the prison notebooks was solely a result of the desperate circumstances in which they were produced. It is precisely the Inquisition’s determination that these notebooks are “idiocies, deliria, nonsense, silliness, and frivolity” that impedes us from examining the earlier writings for comparison. Because the prison vida was judged unworthy of preservation or imitation, there was no reason to preserve any of the earlier writings. The effect is the inverse of what we saw with Madre Astorch, where an Inquisitional stamp of approval prompted the retro-active compilation and re-writing of the first half of a lifelong autobiographical project. Only because the prison notebooks were preserved in the Inquisition archives—not so that they might be read, but precisely as a register of the determination that they not be read—are we able to see this process of life-censorship from both sides.

One effect of Inquisition’s role in archival preservation and the consequent preponderance of studies of women accused of alumbradismo or related spiritual heterodoxy is that scholarship tends to consider women’s spirituality strictly along a binary of orthodoxy and heterodoxy. Without minimizing the pressure that hostile Church superiors and the Inquisition exercised on the women’s writing, we can find in the vidas evidence of spiritual expression that responded to different pressures. We can look at the “failed” or partial vidas that were never formally censored to gain a more complex figure of the limits of the genre, of criteria that respond to dictates beyond the binary judgment of orthodoxy or heresy. I will close with two such examples. One is the Relación de la vida interior y favores divinos (Account of the Interior Life and Divine Favors) of María de Cristo. We know nothing about her beyond what she herself writes in the 507 folios and the brief introductory comment by her confessor that precedes it in the manuscript. The initial authorization by Fray Joseph de la Huerta, in which he confirms that he ordered María to write and believes “the Holy Spirit guides her pen” (fol. 1v) does not seem to be a retroactive insertion but instead the starting point for the manuscript (it is dated 1671 and the first dated entry in the text, 50 folios in, is 1680).

The narrative begins with the author’s childhood, which she represents almost to the letter according to the Teresan model: youthful zeal, lapse into vanity, death of a parent, reluctance to marry, mystic vision that pushes her to enter a convent. She then begins to detail a series of physical ailments, again echoing Teresa, but whereas the discussion of her early years is condensed, she enters into great and extended detail in her description of her sickness. Unlike Teresa, she immediately assigns a spiritual narrative to her physical symptoms: she is suffering on behalf of souls in purgatory, her pain is a reminder of Christ’s suffering, or she is being tortured by the devil. Instead of a single near-death experience that gives way to renewed spiritual devotion, her narrative becomes a series of physical and spiritual tribulations; no sooner does she recover from one than she is beset by another. The interpretation of physical maladies as spiritual tribulations is hardly uncommon in

vidas; as Jennifer Eich notes, many early modern spiritual writers enacted a “rhetorical transformation of [their] physical illnesses and emotional sufferings” in order to show their own spiritual strength (

Eich 2002, p. 209). They were exemplars insofar as they could convert their physical sufferings into metaphor. María de Cristo seems to fail at the metaphor-making stage; she is unable to draw spiritual conclusions or comfort from her bodily pain. Pages of detailed narration of physical torments at best end with a summary that it must be God’s will. For instance, after a bout of pain in her side and an attack by a “madman in the street” she suffers a:

persecution that lasted all summer...and it was that there were always disgusting animals like bedbugs raining down on me night and day...their bites made my body tremble and I could see them coming across the floor in throngs, the ones that came from above were not enough and at night...it was such that I could not rest for an instant, and the suffering was so great that many times I end up lose [sic] patience. I owe everything to God for holding me thus in His powerful hand.

(47–48)

The complaints and details of suffering overwhelm the obligatory note of recognition of God’s will.

The time of writing and the past time being written about are joined, not in a spiritual camino, but by the recurrent thread of sickness. Thus, even after she has recovered from the “persecution” described above and can spend “forty days enjoying all the mysteries of my Redeemer and Father” (a jump with no further description, no description of method or progression), she cannot write more because “I am so unwell that I cannot write them [the details]” (49). And shortly after, she is plunged back into a near-death illness:

His Majesty out of his great mercy put me in a fate or place in hell where I suffered what no tongue could say. The infernal enemies overtook me, giving me great punishments and burning this miserable body. And what I felt most and in particular was that that [sic] with great cruelty they pulled out my teeth and molars and afterwards they cured my mouth inserting flaming torches which rapidly tortured me, and they carried out this punishment for a long time, I was all blistered and with sores on my mouth such that I could not even drink water, because it was also all cracked as if it had been opened with a knife. My bodily pains were so bitter because every limb suffered its own trouble, and in the end I found myself as if I were on the cross. Afterwards they scraped me, removing my entire skin, which was like an entire shirt you take off.

(52)

The description of her torments continues, and while she frames it all as demonic revenge for her great patience, the spiritual frame is overwhelmed by the details of agony: “pinches that drew out my flesh in chunks, such that I was covered with bruises” (ibid.); “the rest of my body wasn’t just black but it was also covered with bruises and today, five months after this happened, I still have some on my body” (53).

The narrative continues in this vein for folio after folio: physical and spiritual torments narrated in great detail followed by brief accounts of celestial visions or ecstasy, which she often protests that language is insufficient to describe. While this is a common mystic trope, the mystic writers whose works transcend experiment and innovate with language in order to at least approximate the ineffable; María de Cristo, in contrast, tends to “gozar” in silence but suffer with prolixity.

María de Cristo seems to recognize her spiritual life, and thus her spiritual diary, should conform to a model of progress. When she cannot find this narrative from within her experience, she stops writing: “I will say no more on this point so I am not tiresome, as pretty much the same things that happen to me from one year to the next” (101). Instead of expanding at length on her temptations to self-censor, here she truly does censor herself. The contemporary reader may find early modern spiritual diaries to be mind-numbingly repetitive, but we can see here that only some experiences could justify repeated narration. Pain, torment, and desolation without solace did not justify narration.

18 This limit is confirmed in another vida, one which fails on the most basic level of connecting a spiritual and biographical life. This fragment of “A nun’s account of her method of prayer and the mercies she receives and it does say her name or convent” (“Relación que hace una monja de su modo de oración y mercedes que en ella recibía y no dice su nombre ni en qué convento”) is buried in a miscellany of Discalced Carmelite nuns’ papers from Andalucía. It might be supposed that, at the time of writing, the nun’s name and identity were known, but if we look at the text itself, there is reason to suppose that the failure to attach an identity (much less advance to the stage of exemplarity) is not accidental, but instead is both cause and effect of the failure to narrate a successful spiritual identity. Like María de Cristo in the selection cited above, this author finds herself unable to narrate a camino out of a pit of despair. She hits the limit of what can be retroactively edited into a tale of darkness emerging into light, and thus the limits of what can be written.

The account begins fairly conventionally, with the nun admitting her ignorance of interior prayer but also declaring her willingness to learn from her superiors. She finds it difficult to focus (“I could not in my last prayers hold my attention on anything in particular because many things occurred to me all at once, without being able to focus on the meditation of a mystery or anything else with perseverance”) (fol. 330r) but she has some early success. Just one folio in, “my intellect and memory were occupied in great things of God, the intellect was then suspended and I could see better than with bodily eyes what I had then understood” (330v). Her initiation into mental prayer is well-guided, and she gives details both of the exercises her prioress assigns and those she takes from her reading of Teresa and other devotional texts. Rapidly she achieves insight into fundamental mysteries, such as “how God can fit inside the tiny confines of a man because I could see within myself an infinite place, a deep space” (ibid.) The metaphors and visions repeat the visions of predecessors; to this point, the vida almost seems almost to imitate its models too well, to the point where one cannot glimpse any sense of a unique individual behind the universal soul. She alludes to periods of “dryness” but only in passing, as a condition out of which reading Teresa can lift her. She even suggests that her own writing might take the place of Teresa’s in this capacity, that her own “book of memories” could help “when I found myself with some spiritual trouble or temptation, as I have had some harsh ones” (332v). Yet paradoxically, she writes that she disavows the impulse to write: “I felt the desire to write a book of memories...but in order that no one read my papers, I let it go” (ibid.). One has the sense at this point that the disavowal of writing is merely an imitation of similar gestures in previous writers, as the text itself would seem to be the proposed book of memories.

Yet after several more accounts of rapturous visions, narrated in richly poetic spiritual imagery, this text veers from its models. Somewhere approximately a year after her entry into the convent, she writes of a moment of intense joy and illumination that is followed by a terrible depression. Before, she continues “my troubles have been few” but now “they have been constantly increasing, I was without God and He hid himself from me when I desired Him with greatest longing...my soul could not withstand such spiritual solitude and absence in which His Majesty left me and so I turned to the temptation of ire and I was coming undone and I turned against God as if He were an enemy” (fol. 337v). This time, she is not able to find solace in Teresa or through meditation.

She sinks into a “deep sadness...so depleted that the very use of my senses made me sad and I did not wish to speak a word, I could not on the outside hide this great melancholy” (fol. 338r). The “infinite deep space” in her soul that earlier showed to her how God could exist in her interior now is just an empty abyss. Each time she attempts to return her thoughts to a spiritual framework, her mind wanders to things that she feels are inappropriate for the genre of spiritual autobiography: “the [troubles] that I have now I don’t know if I can manage to say them nor are they things meant to be written” (ibid.). In her darkness she turns, as she reported having done successfully in the past during, to mystic literature for guidance, this time to San Juan’s “Dark Night of the Soul” (“La noche oscura del alma”).

I read “The Dark Night” by San Juan de la Cruz, first and second,

19 and so like many of the things that I read [when] I was suffering, Our Father has not wished that I find consolation thinking that I am traveling that same path. Instead, I cannot shake the thought that it is my imagination or a whim. I can only think that I am paying for or that the cause is my sins and that I am out of God’s grace, although on the other hand....I can clearly see that it is as Your Reverence and our mother prioress have assured me and Our Father has a use for my suffering. I desire with great feeling that Our Father (and not so that my troubles might end but in order to be completely one with Him) unload on me as many as He wishes and shorten the time already [of suffering] and clear my mind so I may know Him (338v).

She cannot identify with San Juan’s poem because it narrates a transition from darkness to light, and while it consoles her to see the “camino” that begins in darkness in the poem, she cannot use that identification as a springboard to imitation of the poem’s movement up the “secret ladder” (

Juan de la Cruz 1989, p. 4). The paragraph ends suspended in the darkness in which it began, “I am leaving this became I am in no condition to extend it, I will go back and continue with what I left unfinished” (Anon n.d., fol. 339r) because the only resolution that the genre can accept is the one she cannot find. There are no dates or indications of the temporality of the writing process in the manuscript, but it seems as if she leaves the narrative at this point and returns at a later date, since the next paragraph finds her back on track spiritually, without any reference to how she found her way out of the chasm that was narrated in the previous ones. In the following folios she again experiences “sequedad” but is able to channel it into a moment of spiritual redemption. The manuscript continues for two

folios (verso y recto) after the first break and then breaks off definitively and mid-sentence, suggesting that writing continued but the remaining

folios were lost. It is impossible to know how or why the

vida ends here, and how or why the

vida was separated from the identifying characteristics of its author. However, in its truncated and anonymous form, it gives a glimpse into the appeal but also the limits of the

vida as a genre. The template of the

vida espiritual was flexible enough to admit poetry, dialogues, drawings, doubts, raptures, advice, temptations, and meditations. But if could not stretch to narrate a life divorced from a chain of exemplarity, an author unable either to learn from others or to offer any example of spiritual transcendence herself.

Multiple pressures—some originating in the period of the texts themselves, others stemming from more modern trends in scholarship and publishing—have led scholars to privilege a small subset of early modern vidas. Teresa’s Libro de la vida is the standard, and while important work has been done to expand the canon of female spiritual writers who followed her example, we still have mostly concentrated on vidas that adhere “successfully” to her model. Furthermore, we have tended to consider the vida as a distinct genre, ignoring the degree to which first-person writing in the period spread across diverse textual forms and was only subsequently edited into discrete lives. Thus while we are correct in seeing in the newly emerged vida a new form of modern feminine, interior spirituality, we have missed the opportunity to see how this new self emerges through and out of other forms of representation and writing. Rather than placing Teresa and a few other disciples in a separate category from the hundreds of women who have left us some form of incomplete, incoherent, or illegible self-writing, we might read them as all emerging from an (early) modern appropriation of writing for the process of self-fashioning. It is only to be expected that some fashioned selves were more successful than others; the entire archive, or what we can access of it, allows us to get a better sense of the contours of success and failure for women seeking to authorize themselves through self-authorship.

The self-fulfilling historical process that preserves “successful” (coherent, complete, edited) vidas and condemns their rough drafts or the failed attempts to oblivion cannot be reversed: we can only work with what he have. However, we can be careful not to further the process of tautological selection by editing, analyzing, and publishing works that “make sense” without regard to the original process of sense-making (or its failure). In particular, the digital revolution enables us to publish online editions which can permit access to multiple versions, can recreate the original disposition of text on a page, and which open up possibilities for re-imagining the world of textual circulation beyond the model of single authors writing discrete texts that has thus far dominated literary studies. If anything, the digital revolution brings us closer to the world of early modern nuns, as once again previously marginalized subjects gain visibility through self-narration—be it in selfies, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, or blogs—and the self again becomes a project we write into existence through blocks of text sent out into the world.