The research reported in this article is intended to explore what ideas of religious literacy might look like in practice, using the example of one British university. A case study undertaken in 2011–2012 was designed to consider how religion and belief play out across a wide range of front-line staff and student settings, both academic and administrative and, by extension, to draw out the implications for other sectors and settings in wider society.

The study is presented in four parts. First, the idea of religious literacy is introduced and explored in relation to higher education. Second, the methods of the case study are set out. Third, the findings are presented. Fourth, the article sets out key reflections and conclusions.

1. Religious Literacy and Higher Education

The starting point of religious literacy is that there is “a lamentable quality of conversation about religion and belief, just as we need it most” (see

Dinham and Francis 2015, p. 4). The connection to higher education is the role played by universities in reflecting and reproducing wider thinking about religion and belief among their graduates, and therefore among future professionals and leaders. Research indicates that “graduates and postgraduates had higher employment rates, with a greater proportion in high-skilled employment, lower unemployment rates, lower inactivity rates and higher median salaries than non-graduates” (

UK Graduate Labour Statistics 2015). High-skilled employment is defined as managers, directors and senior officials; professional occupations and associate professional and technical occupations, suggesting that decision-making and leadership are key features of graduate job destinations. This puts them in positions of greater influence than non-graduate counterparts and their approaches to the full range of identity issues, including religion and belief, in workplaces and the public sphere is critical.

This is problematic because of a tension between global and local prevalence of religion and belief on the one hand, and widespread assumptions of secularity in universities on the other (see

Dinham and Jones 2012). It has been argued that universities are a good place to start for at least four reasons. First, they are places of peculiarly intense encounter, especially but not exclusively among young people. Second, they are often even more plural and mixed than the rest of society around them, though sometimes the precise opposite is true—which brings with it a different set of problems. Third, they are also conceived of as places where debates about interesting and difficult issues are encouraged. Fourth, universities embody what liberalism takes to be essential freedoms—namely, freedom of speech and freedom of thought—yet religions are sometimes seen as an obstacle to such freedoms. Universities can be understood as reflecting and reproducing a particular post-religious way of thinking which tends to reject religion as distracting nonsense. As these assumptions are magnified in university settings, they are part of the formation of minds which underpins the conversation in wider society, and can therefore be taken as important actors in the future of religious literacy.

2. What Universities Think about Religion and Belief

Research undertaken with Vice Chancellors and other staff in 2009–2010 found two key elements—stances and drivers—which have underpinned the developing conception of religious literacy since (

Dinham and Jones 2012). In terms of the stances the research found a typology in four parts (see

Dinham and Jones 2012). For some, society is conceived of as a secular space where public institutions remain as far as possible neutral and education avoids mentioning religions or belief. We called this group ‘

soft neutral’. A similar but firmer line actively seeks the protection of public space from religious faith, asserting a duty to preserve public bodies, such as universities, as secular. We called this group ‘

hard neutral’. Others saw religious faith as a resource upon which society can draw. A larger number of the VCs we spoke to took this view, with many stressing that their campus is friendly to religions and religious people, and comfortable with religious diversity. We called this group ‘

repositories and resources’. The fourth approach aims to offer education ‘for the whole person’, incorporating a specifically religious or belief dimension. This perspective was more common in universities which were founded as religious institutions. We called this group ‘

formative-collegial’.

In terms of drivers, we asked what sorts of matters about religion and belief preoccupy Vice Chancellors (

Dinham and Jones 2012). They were concerned about legal action arising out of possible discrimination on the grounds of religion and belief; about campus extremism and violence; about being able to market their universities to domestic and especially international students of all religion and belief backgrounds and none; and about what they call ‘student experience’.

These earlier research activities led to the evolution of a theoretical conception of religious literacy as a framework in four parts—category, disposition, knowledge, and skills (see

Davie and Dinham 2018).

3. The Religious Literacy Framework

First is the challenge to understand religion as a discursive category, relating to and often at odds with a real religious landscape which is widely perceived in outdated terms. This element draws especially on sociology of religion to understand dramatic change in recent decades to become more plural, more secular and more non-religious, as well as continuingly Christian in the West (

Woodhead and Catto 2013). New conceptual tools have also become available for how to think about religion and belief critically, including how to think well about assumed secularity (see

Dinham and Francis 2015).

Second is the challenge to understand dispositions—the emotional and atavistic dimensions which are brought, often subconsciously, to the conversation, especially those which are indifferent or hostile on the one hand, and those which result in the evangelical on the other.

The third element is knowledge, based on identifying what is needed in each specific setting. It is obvious that nobody can know everything, and an engagement with religion and belief as lived identity, rather than fossilized tradition, has emerged which disabuses the notion that one can and ought to learn the A–Z of a tradition in order to be religiously literate. Rather, it is about recognising that the same religions and beliefs are held differently in different people and places, and present varying challenges from setting to setting.

The final element is skills, translating knowledge in to practical encounters which meet the needs and challenges in that setting. For example, the goal of avoiding litigation or violence will require different knowledge and skills than the goal of supporting work-based diversity and inclusion (though they may overlap).

4. Method

These theoretical issues, and the religious literacy framework, form the basis of our analysis in the case study reported here. The university was selected on the basis of convenience and access and because it usefully (and unusually) incorporates elements of all of the university types identified by Guest et al. in their study of Christianity in the Universities (

Guest et al. 2013): it is collegiate, civic and campus. The research was in two stages: a survey, and interviews and focus groups. Questions reflected those key aspects identified as important in the previous research referred to above. Principally these were concentrated on equalities and diversity (E&D); widening participation and social mobility; student experience; and fostering good campus relations. We also asked about religion and belief in teaching and learning.

The survey was advertised through the internal communications team in the case study institution, through the Students’ Union and through emails to Heads of Department and Departmental Business Managers. Follow-up messages were sent through all routes to encourage people to respond. The survey was delivered on Survey Monkey and a link was included in all communications. There were 410 respondents, 70% of whom were students (n = 286, including 13 who selected ‘both’), 29% staff (n = 120) and 4 people who did not answer the question. These figures are set within the context of a student body of over 8000 students and just under 2000 staff.

The interviews were predominantly with staff, both academic and operational. Staff in key departments were individually approached via email and/or telephone. The key support departments were all included, with the exception of residential services, who did not respond, and a mix of academic departments from ‘traditional’ and ‘professional’ subjects were included, as were a mix of book-based and practice-led subjects. There were 21 interviews in total, 3 with students and 18 with staff. Interviews were semi-structured, recorded and notes were taken.

The last question of the survey provided a space for people to provide their email address, should they wish to be contacted by us for focus groups. 68 respondents indicated they were happy to participate (13 staff; 54 students, including 2 ‘both’; and 1 unidentified).

Out of those that responded to our further emails, we spoke to two staff (one atheist, one Christian) and had one focus group with all Christian students (n = 5) and one focus group with all Muslim students (n = 3). These were accidental convenience samples—the attendance at all of the groups was self-selecting. The only selection made by the researchers was separate groups for staff and students.

Survey results were quantitatively analysed. Questionnaire and Focus Group responses were imported into a qualitative data analysis program (NVivo) and were coded using thematic analysis (

Boyatsis 1998).

5. Findings

These findings draw on both the qualitative and quantitative elements of the research throughout. The case study which emerges is indicative, not representative, and draws attention to key issues which might be taken forward in further strategic development work and/or research. In the discussion, ‘students’ refers to undergraduate and post-graduate students and those who identified as both staff and student in the survey. ‘Staff’ includes operational and academic staff. Where we refer to both student and staff, we use ‘members’—as both groups constitute the members of the institutional community.

6. Institutional Stance on Religion and Belief

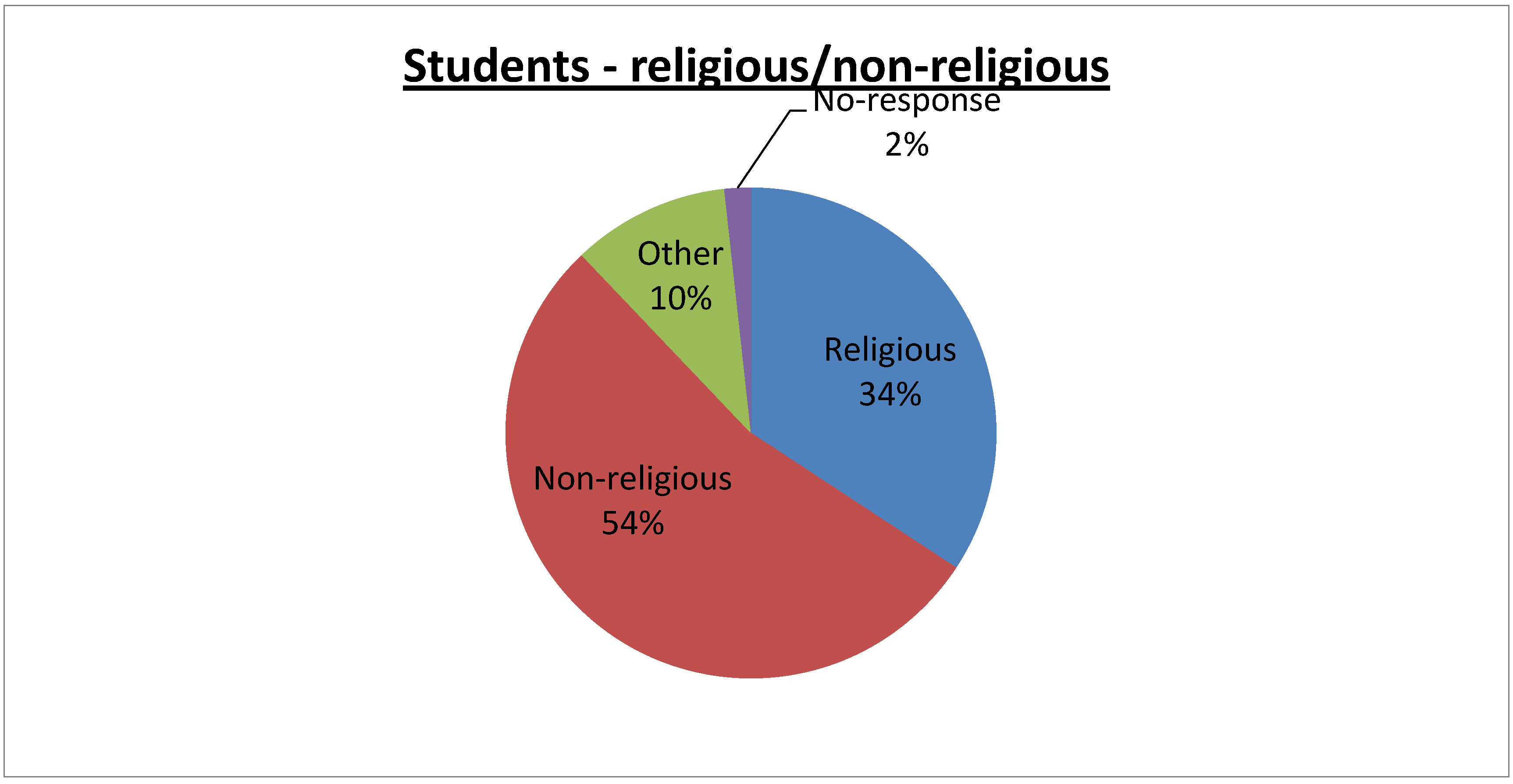

The level of religious identification within the institution, and especially amongst the student body (see

Figure 1), is broadly in line with what could be expected reading from the 2011 British Social Attitudes Survey, where it was found that the general population of the UK was approximately evenly split between not religious and religious.

1 That survey assumes that ‘other’ (meaning pagan, spiritual and other religious) would describe themselves with the ‘religious’ responders. Making the same methodological assumption in this study, the figures are 44% religious or other and 54% non-religious (see

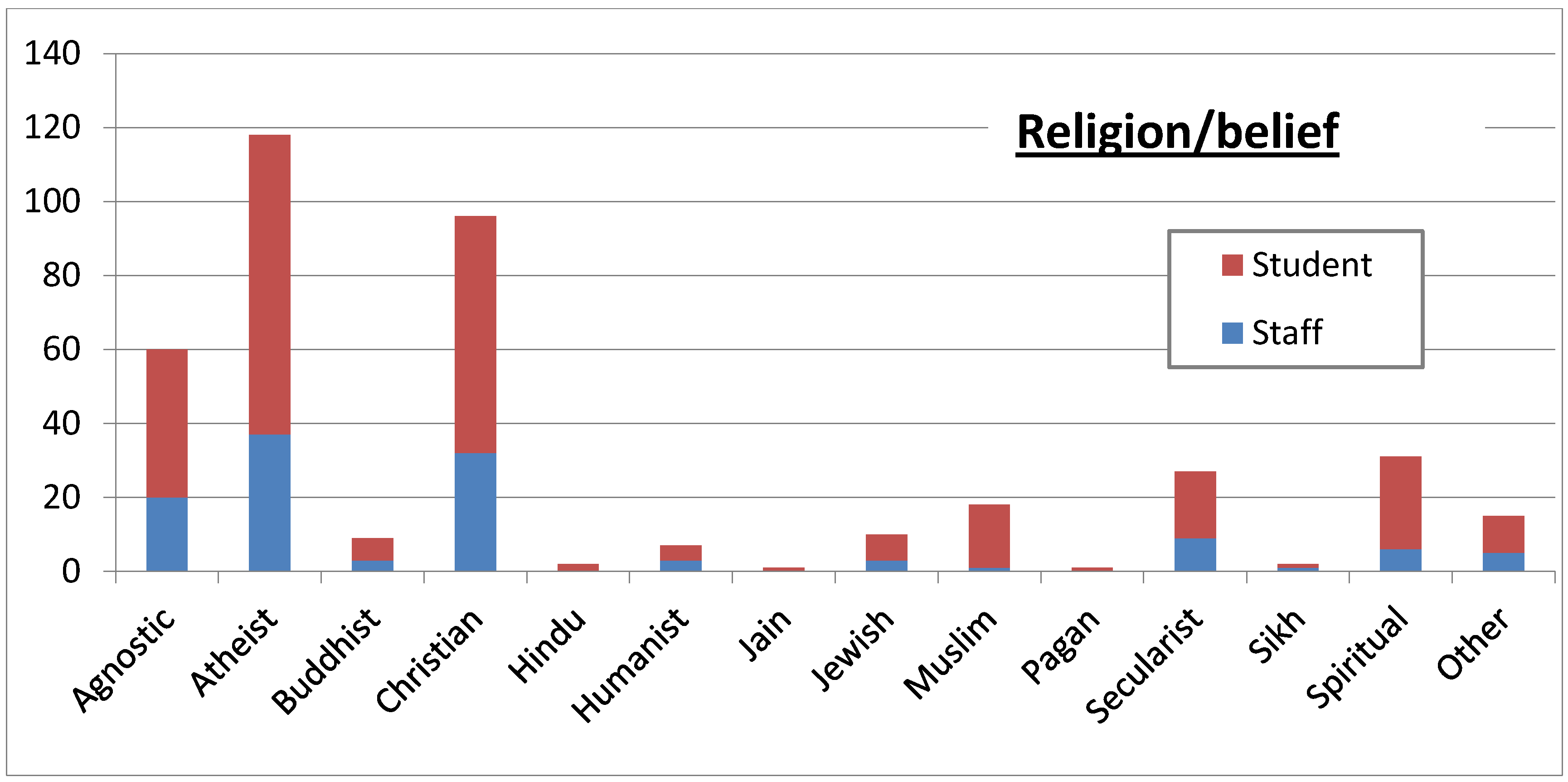

Figure 1). The breakdown by identification is given in

Figure 2.

While people may identify with a particular religion or belief, this study also asked how many people see this identification as significant.

Figure 3 displays whether or not religious/non-religious students see their belief as important to them. There is an emerging body of literature on the significance, not only of ‘no-religion’ but of non-religious identity (

Lee 2015) which is increasingly articulated as a positive construction of its own, as opposed to being merely the absence of religion. The significance of religion and non-religion identities matters, therefore. This study shows that for religious students, their religion is important to them while for a majority of non-religious students their non-religiousness is not important for them. Thus somewhere between half and one-third of students carry their religious/non-religious identity as a significant matter to them, with potential implications for the institution’s approach to their ‘student experience’. The question is what, if any, are the implications of the religion, belief and non-belief landscape of this institution for the stance it takes, the drivers it emphasises, and the distribution or roles of those who are designated to address it. At the point of the case study, none of these issues had been addressed.

Indeed whether or not the institution thinks it has a role depends on the stance it takes in relation to the typology set out above. In the survey we asked ‘Do you think religion/belief has implications for [any of the following areas of] institutional activity?’ The responses were mixed, with the strongest coming in the areas of ‘student admissions’ and ‘staff recruitment’ where respondents overwhelmingly indicated that religion and belief should not have any implication. This can be read as a positive statement that people do not want to see discrimination in recruitment and admissions on the basis of religion. However, there is an alternative way to understand this which asks how religious literacy could play a role as a means for targeting recruitment in under-represented minority faith groups. It is possible that this is obscured by the more immediately obvious assumption that religion should be excised.

The survey also found on the other hand that people felt that institutional operations, such as catering, are an area where religion and belief should be considered (63% of respondents, n = 258) and indeed 80% of Muslim respondents felt that religion/belief had an implication for catering. This repeats a trend found in other parts of the study—to allow religion in technical operational aspects of the university’s life, but to disallow it when it comes anywhere near intellectual life. The boundary between these two is obviously contested and sometimes blurred, but it lies somewhere around a division between activities linked to teaching and learning, and activities to do with student life. Indeed, overall there were conflicting responses around how the institution should respond to religion as a matter of stance—66% of survey respondents (n = 270) said that either “It [the HEI] should maintain the secular character of the institution” or “It should treat faith as not relevant in a university environment”.

Though the majority in this sample tended to wish to ‘maintain the secular character of the institution’ and treat faith as ‘not relevant’, roughly equal numbers of religious and non-religious staff thought the university should actively respond to the practical needs of religious students and should actively break down barriers to religious minorities. On the other hand, many staff reporting a religion or belief wanted to see the university ‘embrace religious faith’ and ‘make religion an important part of teaching and learning’. More detail is needed about what responders meant by these statements: whether these are inflected through a liberal notion of a market of ideas, in which religion and belief are accepted as playing a legitimate part; or as an aspect of religious evangelisation. This is a central issue for a conception of religious literacy as starting with clarity about the category of religion and belief. This connects immediately with stance: what counts as religion or belief, what is included and excluded, and how is it to be thought about? A Habermasian interpretation of the institution would imply a taking seriously of the facts of religion and belief, while continuing to propose its presence only in the language of ‘public reasons’ (

Habermas 1995). Contrarily a post-secular view might entertain an interest in the religion and belief which is present as a source of learning and/or formational enrichment (

Baker and Beaumont 2011). This draws attention once more to the absence of clarity on these issues within the institution. There are some issues which might be construed as pointing in particular directions, however. For example, religious staff thought the university should ‘do more to tackle religious extremism’, which suggests that these views could be understood as part of a moderate outlook which has, in common with non-religious views, a contextualised idea of public faith in the university. That said, it might equally be construed as an expression of anxiety.

It should also be noted that, were the data in

Figure 3 generalised to the whole institution, approximately 16% of the student body would feel that the institution should ‘provide better opportunities for religious and spiritual development’. This would be around 1355 students. This constitutes a significantly larger minority group than for ethnicity, yet while many institutions have highly developed policy and practice on that aspect of identity, very few, including this one, have equivalents for religion.

In interviews on this point, responses were more ambiguous. In these contexts, most people thought that the university did have a role in responding to the religion and belief identity of students and staff. There was an awareness of the importance of religion and belief to some people and it was thought that the university should respect and accommodate religious faith, whilst acknowledging the richness of experience that a multi-faith environment provides students:

“Faith is important for a minority of students but the importance of faith within their lives is huge. For them, if the [University] experience doesn’t respect and engage with that tradition, it will be greatly impoverished.”

Engaging with students’ beliefs and enabling them to learn about the beliefs of others in a tolerant and safe space, was also seen by some as key to the student experience:

“The [institution] has a role and the Department has a role to enable all students where faith or religion is a central part of their lives, the [institution] has a role to facilitate that in an enabling way, so that students don’t feel marginalised because of their religion.”

Others felt that religion is an area in which the institution should certainly

not have a role. This view was particularly expressed in relation to the curriculum, suggesting that religion should be kept separate from teaching and learning:

“No—it’s not [its] business, but a private thing”.

“[I] See it [religion] as outside of education… outside of institutionalised education”

To address the issue of stance expressly as well as implicitly, the interviews also asked which stance they felt best described the institution’s approach. The responses showed that there was a strong sense that the stance of the institution overall is considered to be ‘soft-neutral’. It was seen to tolerate and accommodate religion, but not to promote it. Some—but not all—added that they saw the academic role of the institution as necessarily secular, even while acknowledging the place for religion and belief outside of the lecture hall. They felt that religion and belief should not enter in to teaching and learning because there scientific method has hegemony.

Within academic departments, however, there was a greater interest in the ‘repositories and resources’ approach, and a growing awareness of (and in some cases desire for) the ‘formative—collegial’ model. Some people thought that issues around religion and belief are aspects of the identity-exploration and formation which education engenders. However, there was substantial variation between departments and also in how people saw their department and the institution as a whole. Several people commented that it was hard to place the institution into any one stance, as different aspects or areas adopt varying approaches. This research indicates considerable internal diversity, and that quite often the approach taken can be a product of individual staff’s own outlooks, attitudes, sympathies or beliefs, rather than an indication of an institutional stance.

7. Meeting the Needs of Students and Staff Reporting a Religion or Belief

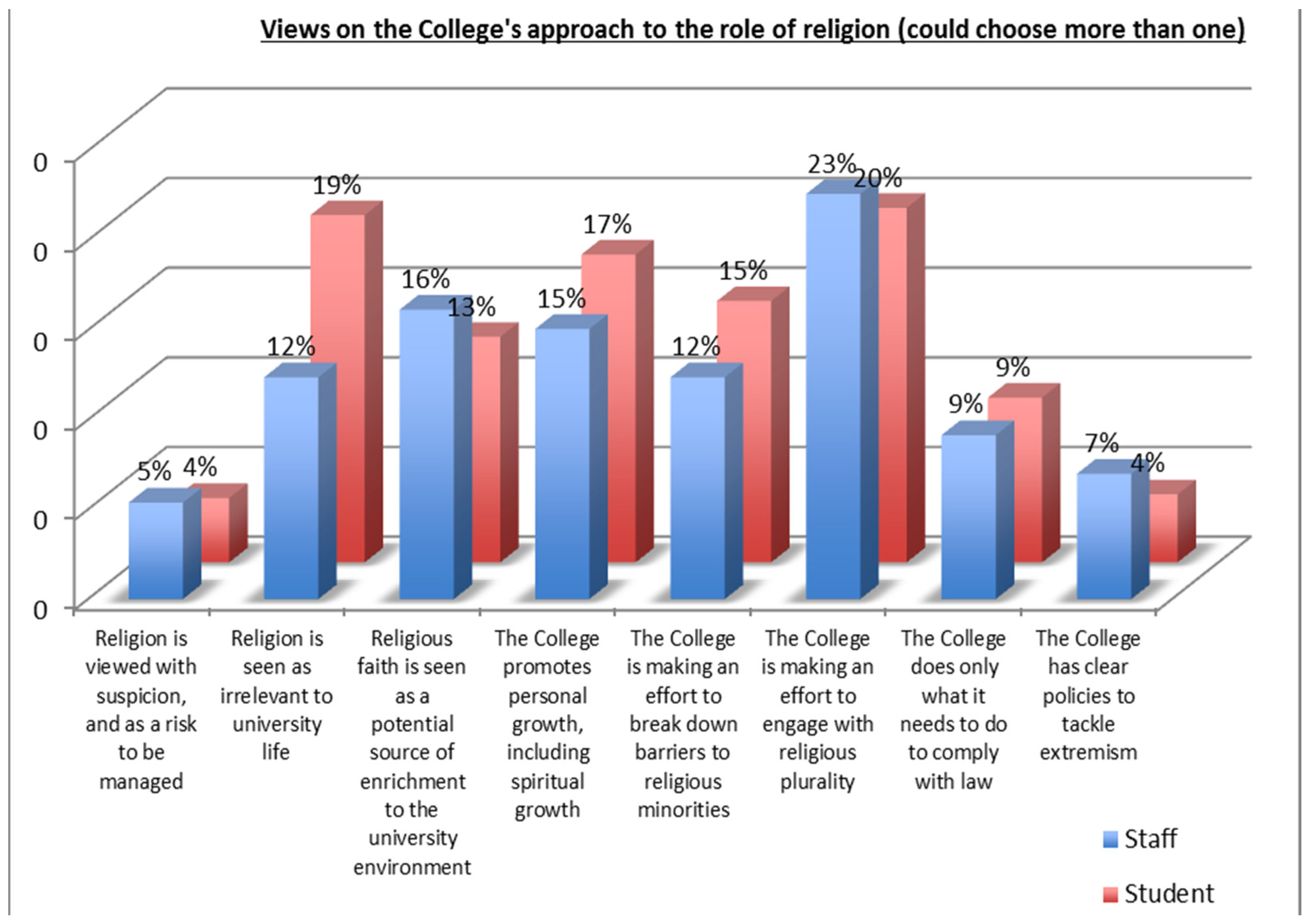

The research asked what approach participants thought was taken towards religion in a number of specific areas (

Figure 4). It was possible to select more than one response to this question and there were 186 selections by staff and 501 by students. In order to make the responses between staff and students comparable,

Figure 4 shows the responses as a percentage of the total responses from each group. Around 20% of both staff and students responses suggested that ‘the institution is making an effort to engage with religious plurality’. However, around 20% of the students’ responses also suggested that ‘religion is seen as irrelevant to university life’, in comparison with only 12% of staff responses.

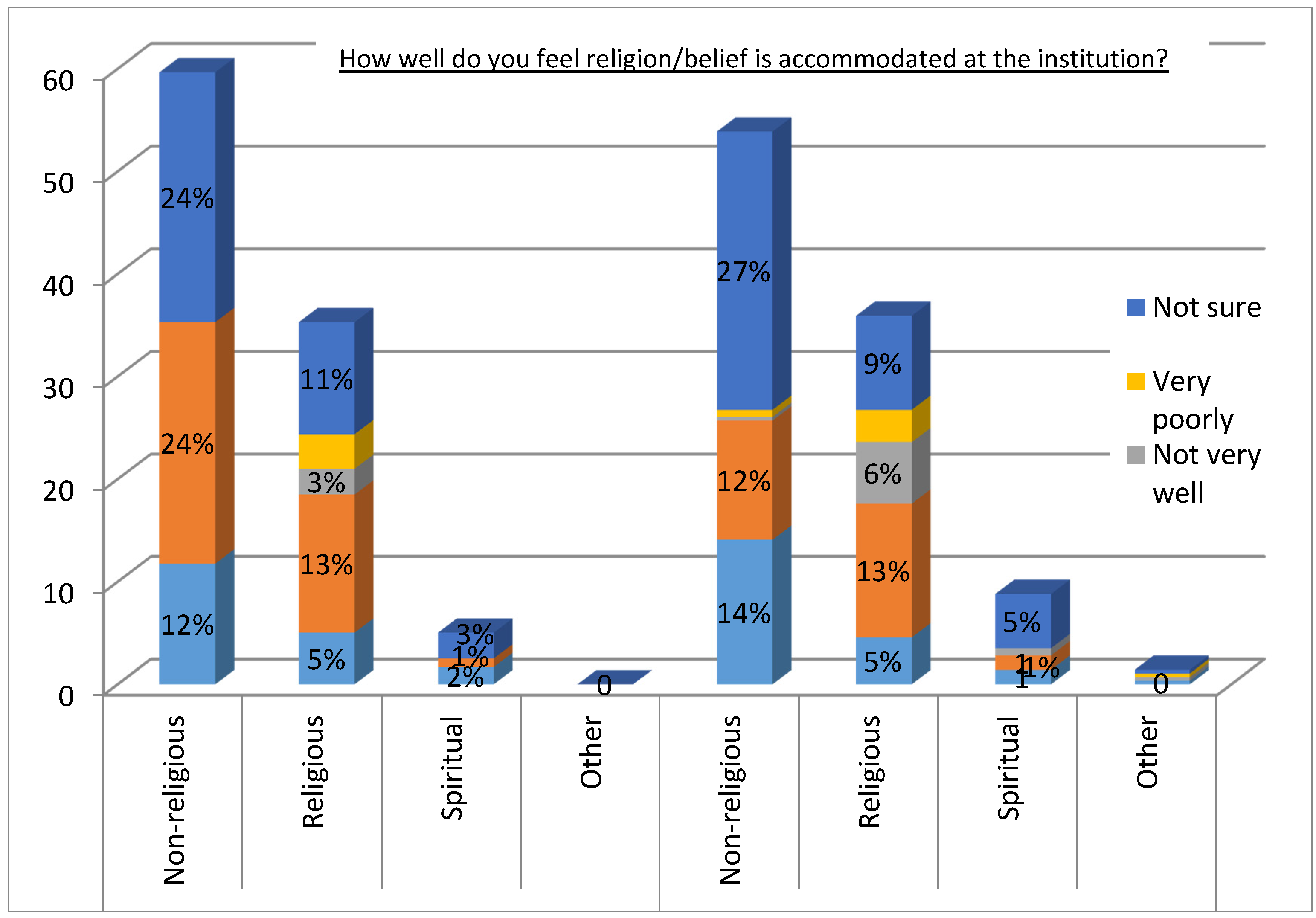

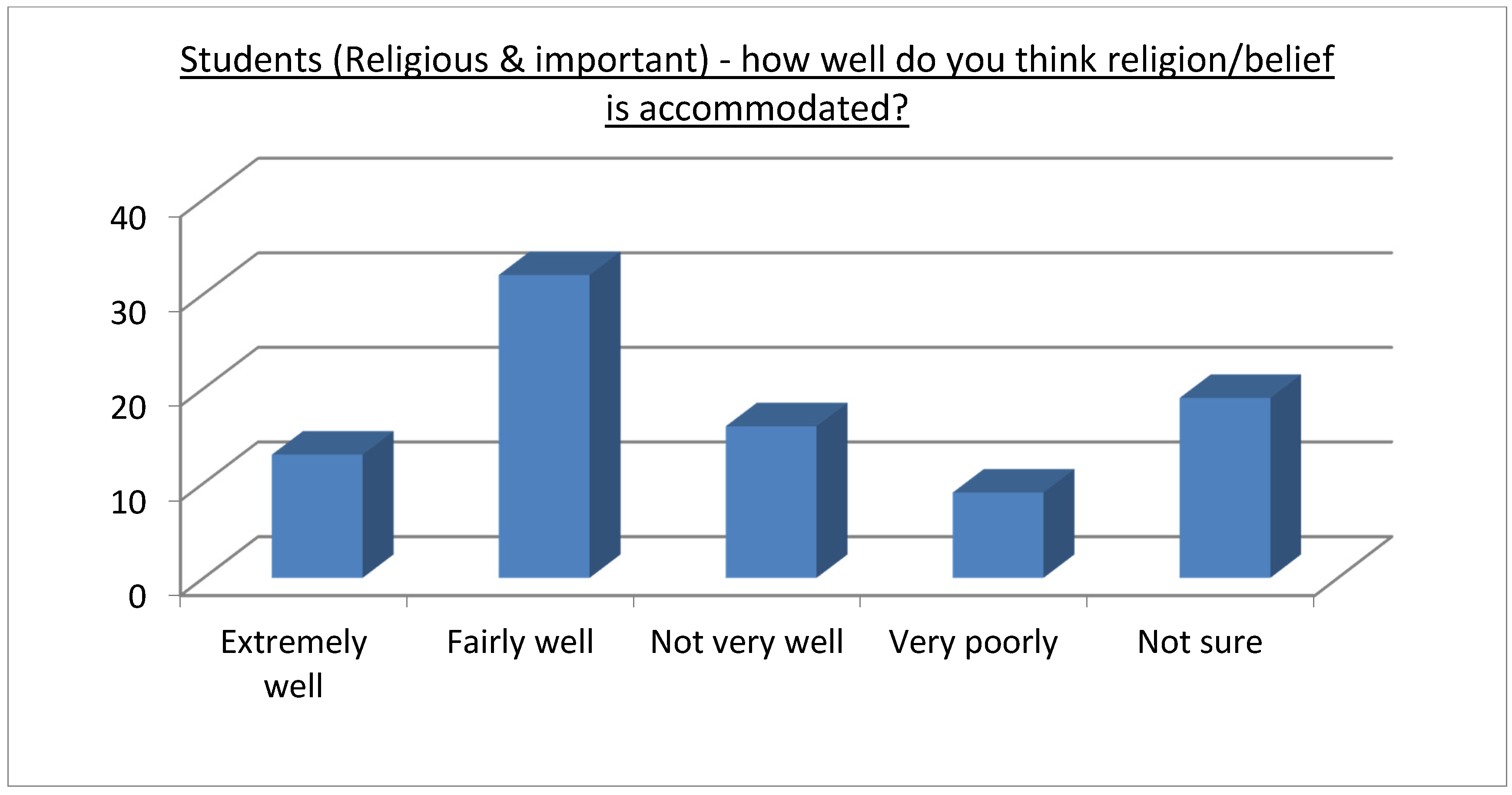

More explicitly,

Figure 5 is based on data from the question ‘

How well do you feel religion/belief is accommodated at [the institution]?’ A key finding is that a significant number are ‘not sure’ (38% of staff and 42% of students). One explanation is that there is minimal visibility of religion and belief as an issue. Another is that ‘accommodation’ of religion is unclear as a notion.

The responses also demonstrate that, those ‘not sure’ aside, the majority of respondents felt that religion/belief is fairly or extremely well accommodated (51% overall, though this falls to only 46% among students). Those who stated they were non- felt this most strongly. This could be because they tend to be less invested in religion and belief issues and therefore less conscious of how these may, or may not, be accommodated (which also fits with the ‘not sure’ category being proportionally the largest amongst the non-religious category). Those who identified as religious had a lower opinion (and were also more sure) of the level of accommodation. It was also notable that twice the number of students than staff thought that religion was accommodated ‘not very well’ and ‘poorly’ (12% of students and 6% of staff). To explore this further, we undertook further analysis on this point (in

Figure 6) of students who are religious, and whose religion is important to them. Just under 50% of religious students (

n = 25) did not think that the institution was accommodating in this regard. If this figure were generalised to the ‘religion and important’ category of students in the whole student population, that would be just under 11% (

n = 885) of the institution’s students who felt that their religion was not well accommodated.

8. Drivers

Religious literacy also identifies a number of drivers—equality, student experience, widening participation, and good campus relations, as outlined above—and these were also explored these in the case study.

8.1. Equalities & Diversity

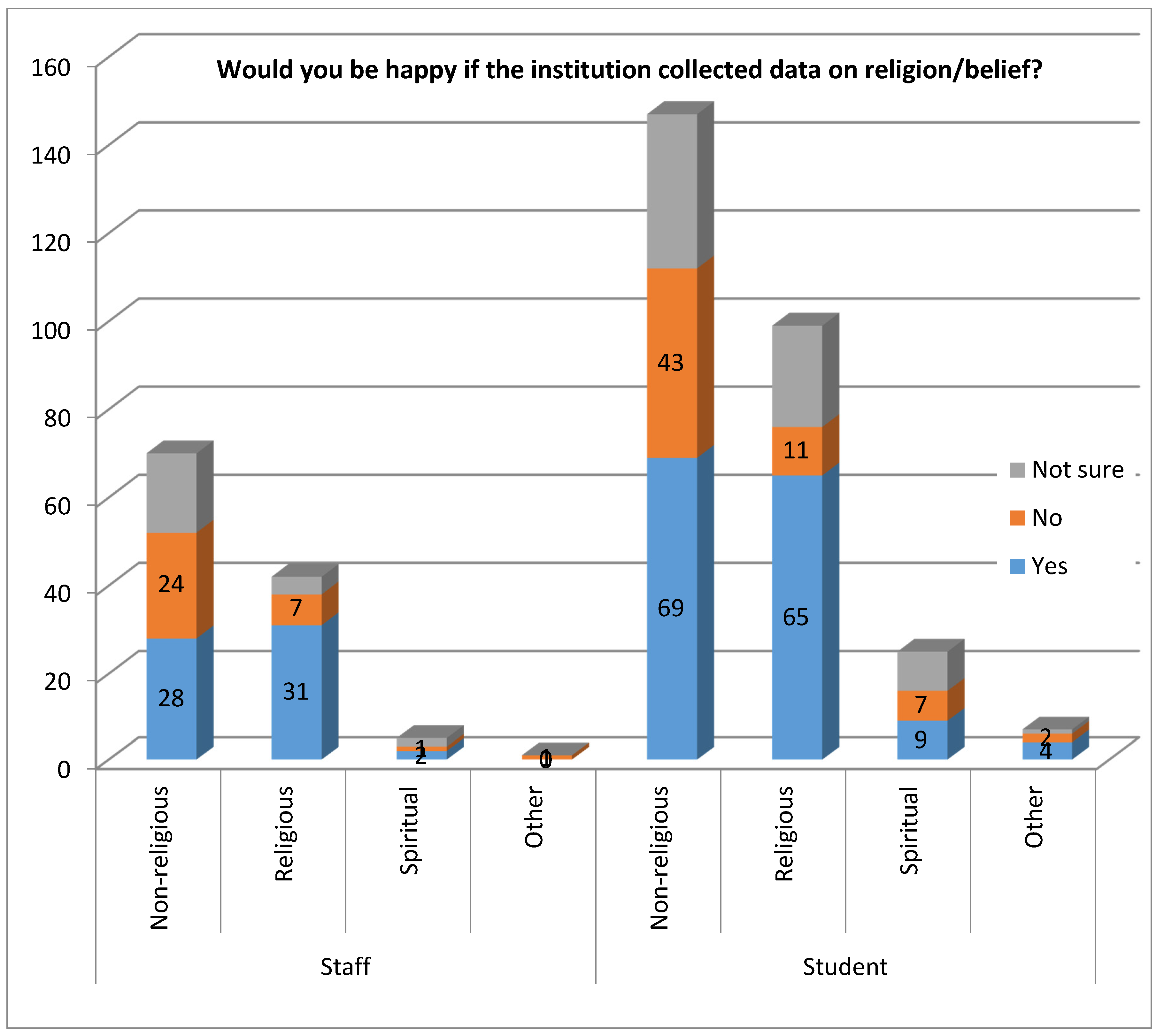

This institution, like many in the sector, did not currently gather data on the religion or belief of students or staff. There were questions about this in the interviews, and all except three respondents said that they would be happy for the institution to gather this data. This question was also asked in the survey

2. 51% (

n = 210) of respondents said they would be happy, with 23% (

n = 94) not sure, 25% (

n = 101) saying no and 5 respondents not answering. For both students and staff responding ‘yes’, there was no notable difference whether the respondent was religious or non-religious (see

Figure 7), but more non-religious than religious responded ‘no’.

Again, staff appear to be more sceptical than students, with approximately similar numbers saying the institution should monitor religion as saying it should not. Out of the three interview respondents who felt that this information should not be gathered (all of whom were staff), one felt that, whilst they personally would not have a problem, it could be an issue for Muslim students who could feel somehow targeted. The Muslim students we interviewed said they were happy to provide data on their beliefs. Another respondent questioned what value religion monitoring could have, but also thought that asking this question would assume that belief motivates actions, which he doubted. The final person to say they would not be happy to give this information was because:

“…[you] can’t convert beliefs into a tick box answer. Most people live religion or non-religion in complicated ways. To encourage them to form an identity that’s hard and fast is quite regressive”.

This point is made in the wider literature, for example in Woodhead where she points to the deformalisation and mixing-up of beliefs and faiths (see

Woodhead and Catto 2013), alongside the increase in ‘believing without belonging’ that Davie has previously observed (

Davie 2015). Monitoring policies would therefore need to reconcile this de-formalisation of the religious landscape with the impetus to improve student and staff experience against a background which still appears to be substantially populated with forms of religious belief.

Due to a methodological commitment to maximise response rates by keeping the survey short, there was no control for whether people had similar aversions to the collection of data on the other protected characteristics. This control could be a useful inclusion in a future study. However, it is possible to compare these data against a national survey on this question (

Weller et al. 2011, pp. 30–33), in which 3911 students and 3056 responded to a similar question (‘

Are you content with disclosing your religion or belief to the University?’) and where the overwhelming response was positive: 80.3% and 84.3% respectively answering that they would be happy to provide this information. A further caveat, echoed in Weller’s report (

Weller et al. 2011, p. 33) is that while respondents may identify as belonging to a particular religion, this does not mean that all such respondents will hold the same beliefs. Adherence to dietary laws, positions on gendered clothing and other issues all differ between denominations, congregations and individuals. Gathering data is an excellent indicator of what may be important to the student and staff body, but the literature is clear that uniformity or internal homogeneity of religion and belief should not be assumed.

The collection of data was also highlighted by several staff as being a potentially useful tool to help gauge the diversity of the institution’s membership as well as ensure that all staff and students are treated equally, regardless of their beliefs. Whilst the student body is seen to be diverse this was only being measured on ethnicity indicators. A second particular issue that arose was in relation to whether or not to make accommodations in timetabling. Most staff felt that examinations scheduling should take account of the major religious festivals of all faiths. In relation to teaching, most staff were happy to allow students to miss classes for religious reasons, but would not necessarily re-schedule them, although most made a point of saying they would help students to catch up. Nevertheless, the desire to accommodate the religious in the practical organisation of lectures stemmed from individual will, rather than a shared institutional commitment—a position which was challenged repeatedly within this sample:

“There needs to be more senior leadership around this issue… no strong strategy at present.”

Staff were unaware who students or staff could go to with any related issues or problems, for example to report an incidence of religious harassment or discrimination. They did not know of institutional policies in this area (and in fact none existed at the time of the case study). Although existing channels were mentioned such as the Equalities and Diversity Officer, Chaplains, and Students’ Union, neither staff nor students were aware of a recognised or formal route for dealing with issues around religion and belief.

8.2. Student Experience

The diversity of the student population was seen as one of the merits of the institution and an atmosphere of openness amongst students was seen to provide an environment in which students can and do learn about other life experiences, choices and values—a key element of a positive student experience. The majority of interviewees felt that diversity, including religious diversity, made the university experience ‘richer’:

“Students need to understand what it means to be part of a global society and how individuals function within that set-up if they’re going to go on to be successful in life… [I] think [the university] should be part of the process that opens up students and staff to difference and the sorts of issues that some people face given their faith backgrounds.”

“We benefit [from diversity] because it widens our perspectives and creates a more dynamic environment”

The interviews signalled a view among staff that students are increasingly looking for a more holistic experience from a university education:

“…students will look for it—to be valued as a whole person and that will include their faith background “

Likewise, just under a third of students in the study (30%

n = 86) felt that the institution promoted personal growth, including spiritual growth. Nevertheless, it was frequently assumed that there was no consideration of religion in the highly visible matter of catering provision, for example:

“[We] need more Halal and Kosher food—for example the Jewish Society buy in food from outside…for their Monday meetings”

“No Halal food is a big annoyance. Recently had Halal sausages in the canteen, but that was the first time in three years that I have seen that.”

This view was supported by some staff, who said that students often raised issues regarding catering needs not being met. At the same time, the multi-faith prayer space was a valued and respected resource for students. However, there was some concern over how this space was managed and tensions had occurred in the past when demand for the space was high (particularly in years when the Christian and Jewish societies were more active). The space was used by a large number of Muslim students and several non-Muslim students said that it felt like a Muslim space and that they did not feel comfortable using it. It was also commented that there had been issues over who got access to the space at what times. Students voiced a need for more space and more choice of spaces. It was also pointed out that there was no prayer space in the student residences, nor was there single-sex accommodation. This latter point was further clarified by one respondent who stated that whilst there was one hall of residence that could cater for single-sex living (in individual flats) this was the most expensive residence and not within the financial reach of most students.

8.3. Good Campus Relations

“…[this] is one of the best places in London to express beliefs—the most tolerant, open.”

Just over a third of students thought that the institution was making an effort to engage with religion and belief plurality and it seemed that students of different faiths and none generally mixed well on campus. This research showed very little evidence of conflict, other than some annoyances around usage of the multi-faith space. Some interview respondents noted that there were natural groupings of students and these were sometimes along faith lines, but that they thought they were in fact largely cultural rather than religious anyway. The distinction between faith and culture is an important one and this conception of religious literacy includes an understanding of differences between the categories of religion and belief, ethnicity and culture. This draws attention to the ways in which religious traditions are internally diverse in part because of differing cultural expressions of the same traditions. Where groupings along faith lines did occur, these were seen by other students as a natural affiliation along shared values and lifestyles and our respondents generally felt that these groups tended to get on well. Again, the open, inclusive environment of the institution was highlighted by several students as facilitating this.

There was the feeling amongst some students and staff that the primary role of the university was to educate and therefore it should not play a role in fostering good relations between faith groups. Some however conceded that the Students’ Union could play a role in good relations. Overall though, most members saw the institution as holding what they described as a neutral position—taking no position which could alienate any particular group in order that a common shared public space could be maintained in to which people of all faiths and none could come. As one student commented, the institution was:

“Slightly positive. Not negative. But they don’t go out of their way to help.”

This is the playing out of a classically Habermasian position within which the institution was not seen to overtly promote interfaith activity and members were not aware of any strategy to actively promote good relations between faith groups, although the presence of the Chaplaincy was seen as evidence of the desire of the institution to take religion and belief seriously. While this perceived neutrality of the university environment was generally seen as a virtue, some assumed that the generally multi-cultural nature of the location of the institution would underpin good campus relations naturally anyway. Such responses were indicative of a passive approach to dealing with issues of religion/belief in general and extremism in particular. Some in the university would have liked to see a more pro-active approach;

“[We] need more interaction—no point to diversity if not interacting”

“I think [the institution] should be part of the process that opens up students and staff to difference and the sorts of issues that some people face given their faith backgrounds”

One interviewee suggested that by not doing anything, or not taking an active role the institution may in fact damage good relations;

“Don’t think it hinders—but it might, for example in prioritising one view over another. For example, they put ‘Merry Christmas’ on the…website, but not ‘Happy Eid’? Perhaps this happens through ignorance?”

8.4. Teaching & Learning

With regards to how issues of religion and belief impact in teaching and learning settings, there was a marked difference between teachers of professional and academic subjects. The former had to deal with these issues because they were educating people to qualify to go into professional settings where they would be working with a diverse body of service users and where they had to comply with equalities legislation, which apply to employers and service providers. The departments providing professional qualifications had a much more direct approach in dealing with the religion and beliefs of students and considered themselves to be more sensitive to the issues.

For the more traditional academic subjects, the issue was more abstract. Whilst some could not see how religion could fit with their subjects, others actively saw religion as a barrier to participation. Some academic staff saw religion as having limited or no place within teaching. Whilst they acknowledged time-off for prayers, for example, they did not think religion and belief should be considered within planning of the curriculum, or in course content:

“Generally [the course is] taught as secular practice. It is a contemporary practice, hence secular… Staff don’t bring their faith into teaching… Teaching must be secular (as in being neutral).”

For some religious students in this study, the privileging of secularity above all presented an obstacle:

“They are accommodating to religion, of people of faith, but the general attitude is that … the general perspective, from the academic side, is that religion is outdated and irrelevant. If you are an academic then religion is, well the two don’t mix… it has seemed like that throughout lectures in a few departments.”

This student went on to say that she felt penalised for expressing her religious viewpoint even when it was relevant to the course content. Some students felt that there was often the assumption that all students are secular, as well as sharing in a generally Western liberal world view, which could leave religious students feeling ill at ease expressing their beliefs.

In departments which did think religion is an issue for curricula, a different set of issues presented. One department handed out photocopies of an out-of-date Anglican text to help students understand some basic tenets of Christianity, and in others staff mentioned that the lack of general religious knowledge was a barrier to understanding some elements of their courses, for example historical and literary.

9. Conclusions

In universities there is even more concentrated debate, plurality, and encounter than in wider society, but also more solidified ideas and assumptions about religion. Universities know they have got to get better at providing excellent student experience. What is also starting to emerge is a bigger debate about the role of religion in teaching and learning. Some disciplines appear to engage with this more than others. The professional subjects like social work and education are understanding that many of their stakeholders are religious and they need to equip professionals to handle this. Others remain entirely uninterested, or even dismissive. This reflects a crucial contention in the rest of society about the re-emergence of religion and belief as a public category at all. Is society and its institutions secular or sacred, or complexly both? To what extent should religion be private or public? Can we leave religious identity at the door? And if so, which door: the canteen; the chapel; the quiet room; the Students’ Union; the lecture hall? (see

Dinham 2015).

In particular we observed six important features in relation to religion and belief in this institution: a clear attitudinal divide between operations and curriculum; a lack of knowledge and understanding of the religious landscape within the institution; differing and localized responses to religion and belief within and between departments; a variation in the approaches of different intellectual disciplines; a very strong desire to promote a good student experience, including a recognition that some students identify as religious; and the presumption that religious and non-religious perspectives are binary—that is either ‘secular’ or religious. This added up to a context which struggled to think and act strategically and consistently on religion and belief, and which enjoined a somewhat vague idea of secularity, often assumed to mean neutrality, without necessarily understanding what that could mean. This reflected much liberal sentiment amongst staff regarding issues of religion and belief, revolving around notions of tolerance and respect, but lacking in direction and surety as to how such sentiment should be made tangible. This was especially the case in relation to teaching and learning. Whilst there was the assumption amongst many that teaching should be secular, this is undefined, and the desire amongst others for a formative—collegial model suggests attention could be usefully paid to how issues of religion and belief are dealt with within the curriculum.

This presents the challenge of attending to religion and belief at a strategic level, including giving some attention to the role that religion and belief plays within students’ lives especially, and how this can form part of the university experience. It suggests that religion and belief should be addressed in formal policies, along with the other protected characteristics in equality law, and serious thought given to whether to measure it in the same way. The role of religion and belief in teaching and learning, and in operations, will require an exploration of the public place of religion and belief which reflects and might inform ideas of their place in wider society too.