In this paper, I examine how possession is understood in Assam, India. We are aware that the larger northeastern frontier of India retained indigenous practices, religious festivals, beliefs in a plethora of exotic goddesses, and rituals, which have continued into the present. This has resulted in cross-pollination between traditional Brahmanical or orthodox Hindu practices and indigenous practices, which in turn has yielded a hybrid world of Śākta Tantra rituals and practices.

This article is based predominantly on fieldwork conducted over four years and secondary texts. During these years, I documented many sessions of “speaking to the dead” in the Tiwa Tribe. The Tiwa are a culturally rich tribal community in Assam, India. The Tiwa’s intersection with mainstream Hindu religion, Śākta Tantra, is rather complex. I first will present a case study of a Mother Tantric who frequently co-creates communication between the living and the departed. Further, I will discuss how Mother Tantrics are seen as community leaders, akin to the religious authority of Brahmins in the Hindu funerary space. Then, I will draw similarities between the rituals performed by the Tiwas to the Deodhani festival in Kāmākhyā, an important Śākta Tantra pīṭha, to highlight the fusion of mainstream Śākta Tantra with the indigenous practices and to show how aboriginal practices also borrow from conventional Hindu rituals.

The interviews were conducted in Assamese and a dialect the Tiwas speak from the Tibeto-Burman language family. I used a translator for the interviews in the Tiwa language.

1. The Tiwas

The Tiwas or Lalungs are a culturally rich tribal community inhabiting the northeast Indian states of Assam and Meghalaya. This tribal community is further divided into the hill Tiwas or the hill Lalungs and the plain Tiwas or the plain Lalungs. Most hill Lalungs reside in the foothills and hilly areas of Karbi Anglong district. One of the distinguishing factors between the hill Lalungs and the plain Lalungs is that Hill Lalungs are matrilineal whereas the plain Lalungs are patrilineal. “According to the legends […] the group of Lalungs who left the hills and came down to settle in the plains did not like the matrilineal system of inheritance and the system of human sacrifice which started when they were under the subjugation of the Jaintia King, Banchere. For these reasons, the Lalungs got divided into two groups—one group under the chieftain Hora and the other under the chieftain Tongora” (

Gohain 1993, p. 98). Soon there was a battle between the two chieftains which led the Ahom ruler to give the plain Lalungs a separate piece of land. In addition, the hill Lalungs lean towards calling themselves Lalungs while their counterparts prefer to be called Tiwas. If one travels east of Guwahati on National Highway 37, to the right one sees the hills of the Karbi Anglong district, which shares a border with the northeast state of Meghalaya. The Tiwas inhabit these hills along with other tribes.

The Tiwas have not been researched as well as some other well-known tribes of Assam, for example, the Bodo, Kachari and Mishing. Birendra Kumar Gohain uses folk culture to trace the etymology of the word “Tiwa.” Gohain relates the name “Tiwa” to the birth of King Sotonga. It is believed that the future king was born to an unwed mother, and soon after his birth he disappeared into a river but was later found in a pond. This child grew to become the king of the clan. Since it was believed that he was born out of water, his people were called Ti-wa—“Ti means water and wa means superior” (

Gohain 1993, p. 3). The folk accounts, however, do not provide a consistent narrative to explain how the Tiwas finally came to be ruled by the king of Gobha. Various histories of the region recount that by the seventeenth century the geographical region of present day Assam was under Ahom rule. The king of the principality of Gobha belonged to the Lalung tribe, and the descendants of that family continue to rule the tribe even today with a presiding King. I had to seek permission from the King before gaining access to the tribe.

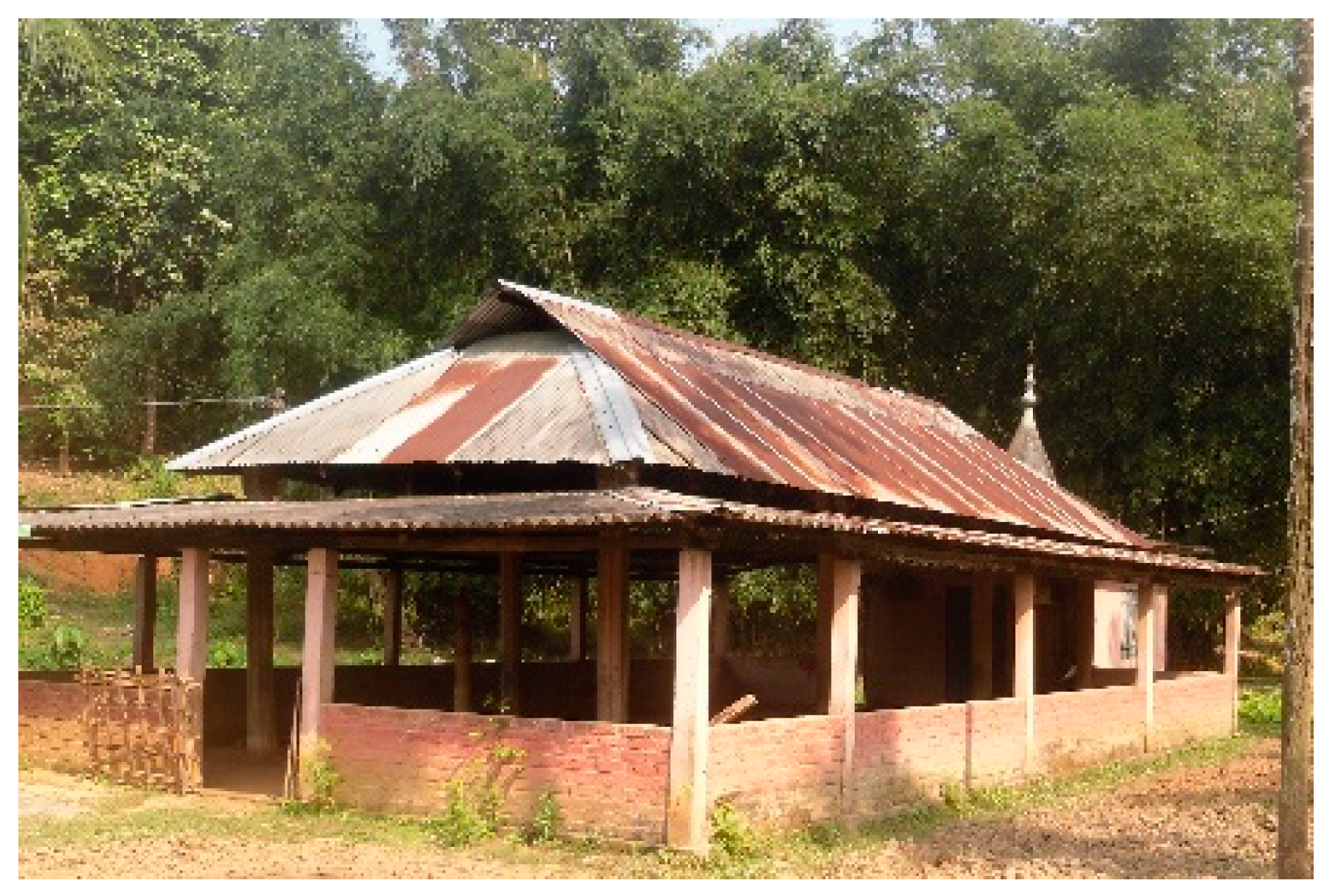

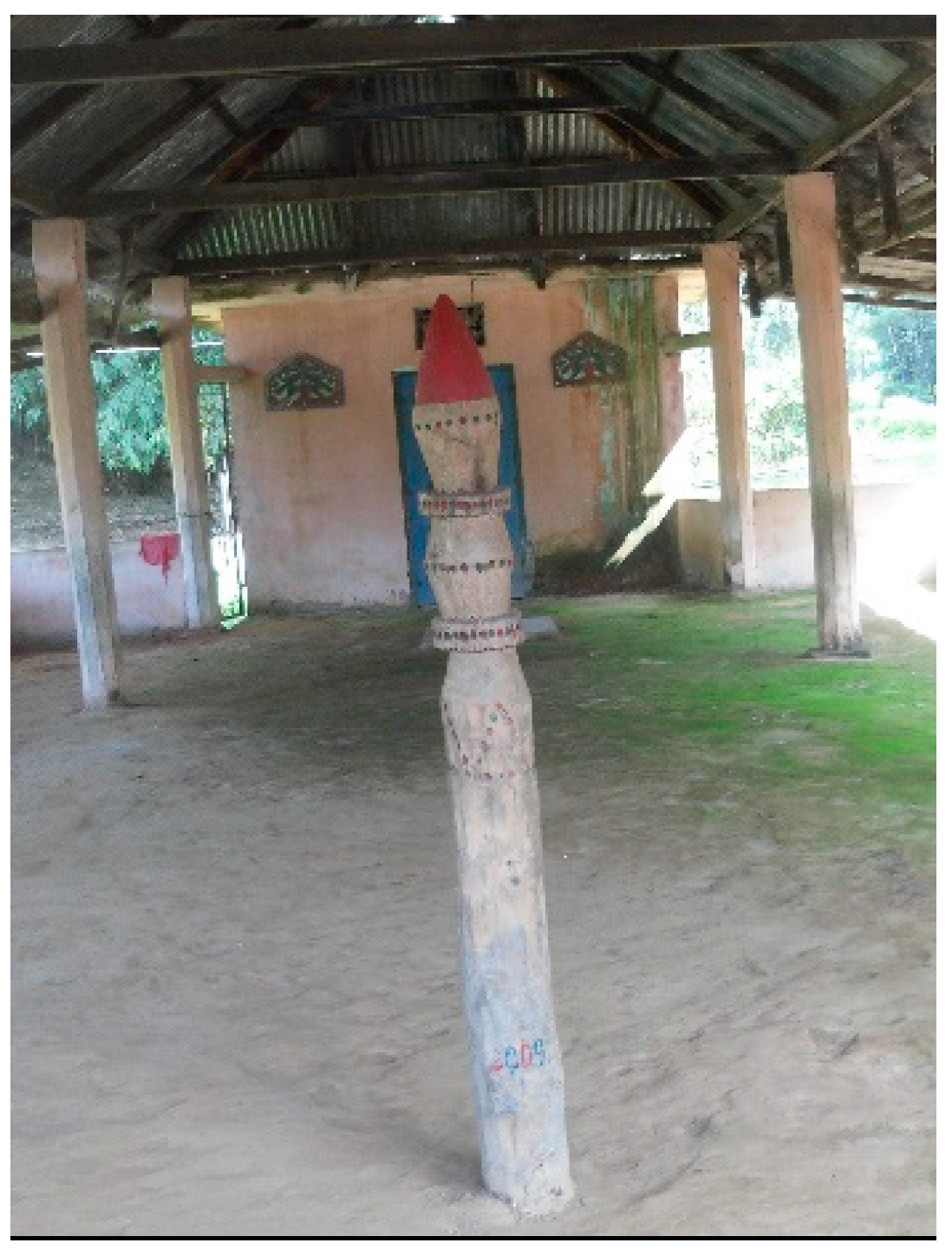

Below are a few pictures from the Tiwa village.

Figure 1 is the temple where the Tiwa Totem is housed.

Figure 2 shows the Totem laying on the floor, which meant the king is currently present in the village.

Figure 3 shows the Totem being raised, which stands for the King being away. The Totem is believed to be presiding over matters in the King’s absence. Photo by the author.

The Tiwas’ intersection with mainstream Hindu religion is fascinating. The Gobha king of the Tiwas traditionally has always been a Hindu. To this date, the royal family continues to worship Lord Krishna. During my fieldwork, I found only a handful of the Tiwa people who embraced the Vaiṣṇava path. Most Tiwas were Śaivites and consider Mahādeva to be their Supreme deity. They also worship Goddesses, though some scholars believe it might be a result of influence by the Koch tribe that live nearby (

Mishra 2004, p. 17). I also found a small percentage of Tiwas to be Christians. Both the Śaivās and the Vaiṣṇavas identified themselves as Hindus, but they avoided associating their rituals and religiosity with the Brahmanical orthodox Hindu religious traditions or with any Tantric transmission popular in Assam. They believed that the Tiwa religious tradition was distinct from the rest of Hindu India’s practices.

To them, one marker of this difference was the absence of Brahmins in their community and of Sanskrit in their rituals. One of my interviewees said, “We [the Tiwas] do not like Brahmins. Historically Brahmins have looked down upon the tribal people and culture. They consider themselves to be superior born and have meted out many atrocities. That is why we do not use the services of the Brahmins. We also do not use Sanskrit in any of our rituals, and we do not practice any Brahmanical or Tantric rituals or read the texts they read”

1. That said, as an ethnographer, I found that the Tiwas’ unique religion was nevertheless a result of a complex fusing or syncretism of orthodox Brahmanical, Tantric and indigenous rituals and customs.

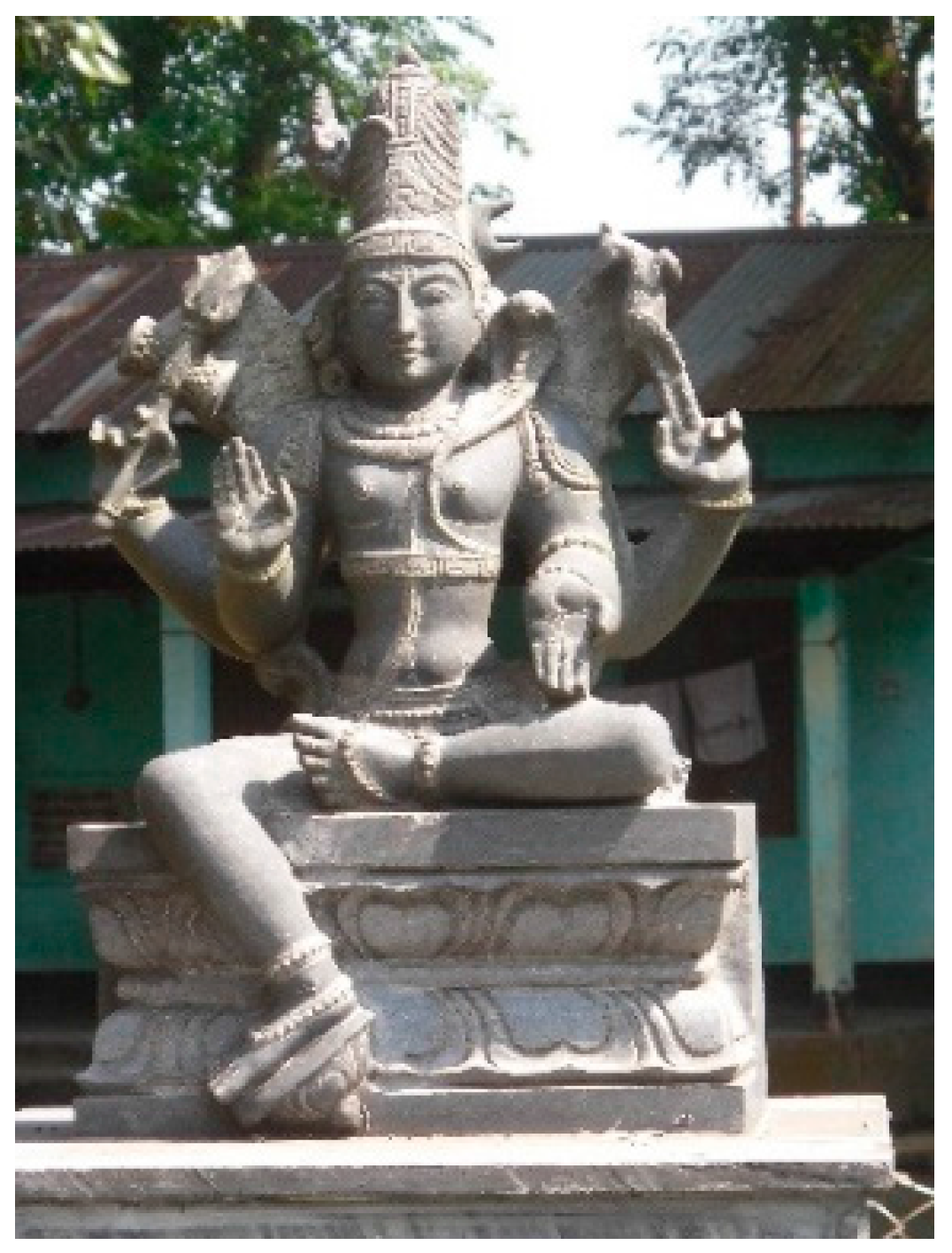

This complex fusing can be experienced in one of the largest and the most frequented temples by the plain Tiwas (as opposed to the hill-dwellers). For example, the

Gobhā Deo Rājā Cāri Bhāi Śiva Thāl—that is, “King Gobha’s Four Directional Seat of Śiva”—was built according to the temple construction guidelines of Brahmanical traditions. As can be seen below,

Figure 4 is a small statue of Śiva tucked away in a corner.

Figure 5 is at the entrance of

Gobhā Deo Rājā Cāri Bhāi Śiva Thāl. Figure 6 is placed in the courtyard of the temple. Photo by the author.

Brahmanical Hindu religious influences were also discernible in many rituals and customs among the Tiwas. Examples include the use of banana leaves on ceremonial occasions, basil leaves used for purification ceremony, and abstinence from beef. In addition, the Tiwa way of worshiping Mancha or Śani (Śani is the planet Saturn, which also has an embodied form known as the god Śani) was like practices directed to the Hindu god Śani, and so forth.

While there were many such similarities noted in my fieldwork conversations and interviews, the departures from Brahmanical Hindu India were starkly evident in the Tiwas’ understanding of death and funerary rituals. The Tiwas did not perform the śrāddh ceremony: the set of orthodox Hindu rituals performed by family members after a relative’s death. Instead, immediately after a death among the Tiwa, the family of the deceased ritualistically consulted a medium known as a “Mother Tantric.” All Mother Tantrics are women, hence the designation “mother.” It is believed that the Mother Tantric is blessed with the ability to communicate between the worlds of the living and the dead.

I interviewed Ma Muni and I documented many sessions in which she communicated with the departed, in a ritual setting. The Tiwas’ understanding of religion and religious ceremonies can be partially explained by employing the work of Henri Hubert and Marcel Mauss. As Jeffrey Carter explains, “Hubert and Mauss believed that religious ideas are ‘social facts’ and that ritual ultimately has a ‘social function,’ for it helps define and maintain social solidarity by working to reinforce shared values and collective conceptions” (

Carter 2006, p. 88). This is particularly true for the Tiwas. In a situation in which the Tiwas feel that their religious and cultural identity is questioned by larger mainstream or orthodox Hindu voices, the tribe needs their indigenous rituals to serve a social function that reinforces their collective identity. Over the years, rituals around death and the cleansing of evil spirits have taken center stage. Most of these ritualistic practices are held in a fashion that enables most of the members of the Tiwa tribe to participate. While there is a host family, the participation of the entire community helps reinforce the Tiwas collective conceptions of religion and religiosity.

My interviews with the older generation in the tribe revealed that community participation in religious activities was paramount in instilling the Tiwa identity in the younger generation. Increasingly, the younger Tiwa generation conflated the indigenous practices of the Tiwas with Hindu Assam’s presentation and understanding of the religion—a classic example of the process of Sanskritization currently in play.

The term ‘Sanskritization’ was coined by the sociologist M. N. Srinivas in 1952. The term refers to a process by which a community, usually a “low” Hindu caste or a tribal group, changes its rituals, customs, ideology, and way of life in order to mirror a “higher” Hindu caste or another community that it wants to emulate. However, it is not a simple cultural imitation. Often the process is driven by socio-economic deprivations and takes a generation or two to show some results. The results are often measured in reference to upward mobility for the group in question. For example, a group might give up eating meat, drinking liquor, sacrificing animals, or change its attire to achieve a better position within the society.

In the context of Assam and this article, equally important is the process of “Deshification,” a term, coined by

Wendy Doniger (

2009, p. 6). Doniger suggests that Deshification is a process by which the Brahmanic religious traditions are influenced by the local (

deshi) indigenous traditions, which then absorbs and transforms the Brahmanic traditions to fit into the local popular culture. In what follows, we will see the process of Sanskritization amongst the Tiwas and the impacts of Deshification in Kāmākhyā.

2. Ma Muni: The “Mother Touched by Gods”

Ma Muni is one of the Mother Tantrics in the Tiwa Tribe. When I first met Ma Muni she was about sixty-three years old, frail, poor, and a warm woman. She was poor to the extent that she lived in an approximately ten feet by ten feet, small, mud hut with a thatch roof. She owned no furniture. She cooked over firewood and owned a handful of utensils. There were ten people, men and women, who had come to consult Ma Muni that day. All ten of them belonged to the same family, and they had come to communicate with the “dead;” one of their own who had passed away seven days back.

After Jagadish, my translator, introduced me to Ma Muni, Ma Muni said: “The king had sent a message saying that someone from America will come to see me. I was very scared, and I asked when? The messenger said, I do not know. I asked for what? The messenger said, I do not know. I told my daughter and son-in-law [points to them in the crowd], “What will I tell her? They said we do not know. Meet her and then decide. But you are like me, [Ma Muni touches my face and arms] you are one of us. You are not ‘white’”

2. This was a moment where I truly understood how ethnicity and possibly even gender may play a critical role in getting access to people and data during field research. Ma Muni’s immediate acceptance and considering me to be “one of them,” I believe, had an enormous influence on her willingness to give me access to her world, her rituals, and the practices she follows.

Ma Muni remembers getting married at about eight or nine. A few years later, possibly when she was approximately twelve years old, as she had her mensuration cycle, she was suddenly caught by the Lord while she performed her daily household chores. She did not know what had happened. What she remembers is that she was unable to sleep for seven days and seven nights and kept hearing voices. Following that, Ma Muni narrates:

When I was possessed (

dhorise) the first time, I did not understand the language of the gods and was not blessed with the knowledge to interpret their messages. I did not have any command over them. I could not ask them to leave me or instruct them to speak one at a time. I did not know how to distinguish between the gods and the

bhūt [ghosts]. But after I was blessed by the shaman, priest and the King, the

Debotā [gods] come to me first. They give me the skills which are required to communicate with the

ātmā [departed soul]. It is only by the blessings of the

Debotā that I am I able to relay the messages. Now the

ātmā’s come (

āhe).”

3

During that period of seven days and seven nights, her husband and her in-laws, who are dead now, called the local shaman. The shaman, the village priest and the king observed her through the period of seven days and night, and at the end the seven days, when the Lord left her, they established that she had the power to communicate with the dead. After a few more weeks, they prepared, and then with a lot of grandeur they gave her the title of cāri bhāi pām māri, or the “mother touched by gods, who knows about the four directions.” On the day that the title was bestowed upon her, the tribe sacrificed six pigs, six goats, a pigeon, a duck and homemade country liquor. After offering all this to the person she was believed to be a reincarnation of, they offered it to the Lord and then to her. Since then (about forty years ago) she has been the medium for the tribe. People come to her after someone has died in their family or to consult her if they believe a spell has been cast on them or their loved ones.

Before we proceed to a session of “speaking to the dead,” it is significant to note the shift in words that Ma Muni uses between the first involuntary experience of spirit possession termed dhorise, which can also be translated as “grabbed,” and the term she uses after the title cāri bhāi pām māri was bestowed upon her. She and the tribe referred to such possessions as āhise, translated as “come” or “has arrived”. Ma Muni, although illiterate, makes an interesting (though perhaps unconscious) distinction between divine and profane speech. I realized over the weeks that she made it a point to say this to all her visitors. She ensured that she was not confused with people whom she and the tribe believed to be fake shamans, people who communicated with bhūt (ghosts) and were not blessed by the gods. We will return to this distinction in the sub-section “On Indian Mediumship and Possession.”

3. Speaking to the Dead

During my first recording of a session where Ma Muni was going to communicate with the departed soul, and in many subsequent sessions, I recognized a fundamental difference between the understandings of the believer and the non-believer. The believing Tiwa understands the powers of Ma Muni as a praxis of everyday actions, which foster an ascetic ethos of devotion, discipline, and meditative focus that leads to her ability to communicate with the other world. The primary incongruity between the believer and non-believer, therefore, is that the devotees recognize the skill to communicate as a gift bestowed by the gods upon their guru, in this case Ma Muni, while outside observers do not. The devotee repudiates the secular skeptic’s view with a testimony of faith in the Mother Tantric and her abilities to establish communication with the departed.

For almost all such possession sessions, approximately fifty to sixty people—men and women, ranging from infancy to the elderly—traveled great distances overnight through the mountains hoping to establish contact with the departed souls of loved ones. Consistently, I observed a distinct change in Ma Muni’s demeanor on the days of such meetings: her skin glowed, and she looked about five to six years younger. I believe it was a combination of Ma Muni being more vitalized and my own projection. I tried to inquire more about this shift in her looks. But Ma Muni simply said that it was because of the presence of the

ātmā. The other distinct difference from possession days and the other days was that Ma Muni would be muttering to herself. Her son-in-law explained to everyone present that her mumbling signaled the arrival of the

ātmā, and that what appeared to be mumbling was in fact Ma Muni’s communication with the other world. Pictures below from the session.

Figure 7 is of people waiting for the session to start. And in

Figure 8, the son of the departed soul is giving permission to Ma Muni to make contact with his father.

Ma Muni began the formal process of communication with the other world by cleaning the mud floor and sprinkling blessed water all over the room and on the observers and the family members. She made the water blessed by saying a prayer over the cup of water. Then the family who had sought the ritual of channeling laid out all the items required for this ritual: two kinds of betel leaf, areca nuts, and five smoked gourd bottles filled with country liquor. Ma Muni took a lot of time to ritualistically lay out the items. This can be seen in

Figure 9. Next, she started singing a hypnotic melody. My translator whispered that through her singing Ma Muni was asking for the Lord and the “right”

ātmā to come and reside in her for the time of this session. The “right”

ātmā was a new piece of information. Jagadish and a few family members of the deceased explained that it was crucial to establish whether the

ātmā present was in fact the departed soul they are seeking to get in touch with through this ritual. There are many

ātmā, and if one mistook the identity of the

ātmā, the message relayed would have little meaning. If the

ātmā is evil, it could state things that would bring harm on the family. Finally, we were informed that the

ātmā had arrived. Akin to all other

ātmās, this departed soul came and resided on the bamboo post that was present in the house and Ma Muni was now the interlocutor. The bottom of the bamboo post can be seen in

Figure 10.

On a different day, I questioned Ma Muni on the nature of the ātmā, its language, and her physical feeling when she establishes contact with it, which yielded a great deal of interesting information. Ma Muni stated that when the Lord possesses her, she does not know who she is any more.

Am I an animal, a bird, a mad person, a cow? I cannot tell. I constantly hear sounds when they come, and I cannot eat or drink anything. Sometimes they hold me, possess me for several days. I become a human again when the

Bhagavān leaves my body. There are times when the

Bhagavān possesses me, and then are times I must catch hold of him. See, this family [points to the group of people sitting there] has lost a male member, the husband of this woman [shows me the woman]. Now they must talk to the departed soul to get his news and to find out if there are any hindrances or ill fate that may come to the family. So, I have to catch hold of the

ātmā of the departed soul to get the answers. During this time, I feel very tired, my head spins, and it is not a good feeling. I feel sick. Sometimes I sleep and sometimes I don’t. The

ātmā can be of small children, men, women, old people, and young people. Everyone comes except infants. They do not come because they cannot communicate. We cremate people who died a natural death. That

ātmā is the easiest to communicate with. But if people have died of a severe illness or an accident, we bury their body, and those

ātmā take a long time to come and communicate

4.

Through the next five hours, after the arrival of the spirit, Ma Muni kept her eyes shut, with her back turned toward the audience. There were no physical signs of possession, that is, she did not change her voice, jump, tremble, or show any outward signs of being possessed. She continued sitting in the same position with her eyes closed, calm and serene. For the first hour or so, the family (both men and women) started interviewing the ātmā to ensure that it was indeed the departed soul of their family member. To do this, they asked the following questions: “What was the name of your friend? What was your favorite food? What did you dislike eating? How many children did you have?” and so forth. Ma Muni responded to all the questions (the family believed) as directed by the ātmā. Through tears and laughter, after about forty minutes, the family was convinced that they had the right ātmā. This is particularly interesting as there was something “empirical” about it, that is, the family was checking the identity with facts that Ma Muni, supposedly, would not know.

The next hour was dedicated to checking on the well-being of the departed soul. They asked the departed whether he was doing all right, whether his death was natural, and if he liked it up there. The departed informed them that there was no foul play involved in his death and that he was happy. Next the ātmā warned them of certain illnesses that were looming on this larger family and urged them to be cautious. Following this, rituals to protect the family from the oncoming dangers were discussed. This involved sacrificing a pig. Finally, four hours later, the family offered the ātmā his favorite food, which was consumed by Ma Muni (still with her eyes closed), along with country liquor. Tiwas believe that they fed the ātmā who ate through Ma Muni’s body. Finally, in the fifth hour, they bid him farewell, which was hardest for his wife to do, but she did. The sons wished their father well. Following that, Ma Muni opened her eyes and concluded the session by thanking the Lord and bestowing blessings on all of us.

Ma Muni, via her skills of being a medium, provided a structured ritualistic space in which the Tiwas could meet their emotional and spiritual needs. By means of connecting with the no longer seen—the departed soul—and the unseen—the gods—Ma Muni addressed the urge of many to transcend “self-conscious selfhood,” thereby removing psychological and/or physiological forms of suffering, which is a key motivational element that keeps the Tiwas seeking a Mother Tantric. By playing this role, she is the healer for the entire tribe (

Kakar 1982, p. 119).

The Tiwas also consult Ma Muni if there is a prolonged, repeated illness in the family; when a family has continued misfortunes; or when a family believes that someone has cast a spell. Jagadish, my translator, went on to narrate an incident that happened a few months earlier that led him to consult the Mother Tantric. One winter morning Jagadish was about to take his kids to school, and when he opened his door to leave for the bus stop, he found his patio painted in blood and oil. The presence of fresh blood and mustard oil was a clear sign that someone had cast a spell on his family. So that day Jagadish and his wife went to the Mother Tantric. She told them the rituals they must perform to break the spell. He was required to sacrifice a pig, a bird, and enlist a shaman’s help. Next, he had to take a small quantity of the blood from the sacrificed animals, and while the shaman recited the mantras, he smeared this blood all over the front porch to break the spell. After that the meat was cooked, offered to the Debotā and then eaten by everyone in the community. Jagadish did everything as prescribed by Ma Muni. He went back after a few days to confirm whether the spell had been destroyed, and she confirmed that it had been.

Over approximately four years of research, I heard many comparable stories. Ma Muni and other Tiwa Mother Tantrics are seen as community leaders. They yield a lot of power. They can even overrule the king’s dictate

5. In this way, the Tiwas epitomize the complex negotiations tribes in Assam have developed over centuries between their indigenous religious ritualistic views and “high-brow” Tantric traditions. Before I delve deeper into the world of Tantra in Assam, it is imperative to briefly look at the phenomenon of medium and spirit possession and address the etymology of the term “medium” in the context of my interview.

4. On Indian Mediumship and Possession

Many ethnographic works on spirit or deity possession in India claim that possessions are widespread in Indian religion. The possibility of possession and the reality of being possessed constitute a meta-narrative that is integral to most Indian psyches, irrespective of one’s status as a believer or a skeptic. Yet it remains in the shadows. Lack of open conversations on this subject can be traced back to beginning of modern times where one finds “long standing aversion among educated Judeo-Christians as well as educated Hindus, for whom possession has fallen outside the realm of both reason and social accountability” (

Smith 2006, p. 3). It was largely seen as practices of the illiterate and un-cultured.

In the eyes of a modern intellectual, the practice of possession may signify an unjust social situation or familial manipulation of devotees. The subject of possession also tends to be perceived as primitive, practiced by the illiterate, low castes, and tribes. But as David R. Kinsley writes, “In reading about South Asia, one often gets the impression that possession, along with related ecstatic behavior belongs to the ‘little tradition’ and is thus largely confined to the lower castes and the poor and uneducated in rural areas. However, […] the phenomenon of possession […] is widespread throughout the population […] in both village and urban settings” (

Kinsley 1998, p. 179).

Further, in reference to the scholarly consensus view of possession, Frederick M. Smith writes: “The evaluation of the evidence for deity and spirit possession in South Asia, in both classical texts and modern practice, is framed by prevailing characterizations of such gravity that only with great effort is it possible to escape from beneath their weight—and in doing so it is still impossible to escape their shadow” (

Smith 2006, p. 3). I faced similar challenges while observing and drawing conclusions on possession sessions. I tried to consciously suspend judgment and apply ‘cognitive-sensitive’ understanding, yet I constantly wondered how I, as an ethnographer, could walk the tightrope stretched out between being too reductive or being too gullible.

A quick scan of scholarship highlights that possession has largely been studied under the interpretive frameworks of: (1) medicine and psychology; (2) social and political control; (3) as a feature of shamanism; and (4) to question the validity of ontological and veridical realities. Irrespective of the context, almost all studies split the topic of possession between some degree of good and bad, between demonic and divine, health and unhealthy, and so forth. In sum, possession under different frameworks maintains a thread of binary.

We now turn to address the difference between spirit possession and spirit mediumship in order to determine in which category Ma Muni falls under. Using the distinction proposed by Peter Claus, while problematic in its binary framing, give us a framework: “Spirit mediumship—the legitimate expected possession of a specialist by a spirit or a deity, usually for the purpose of the aid of the supernatural for human problems. […] Spirit possession—which we may tentatively distinguish from the above as an unexpected, unwarranted intrusion of the supernatural into the lives of humans—is far more common than mediumship and far more widely distributed” (

Claus 1979, p. 29). Since Ma Muni’s is seen by her and the tribe as a legitimate, a specialist, and she uses her powers to heal grieving families, as per Claus’s categorization, she falls in the larger category of “Spirit mediumship.”

In addition, it is also helpful to mention Kamil Zvelebil’s categorization of what he called “genuine possession” and “pseudo-possession.” According to Zvelebil, genuine possession is a type of “regulated contact with the sacred,” and pseudo-possession is the “poetic conventions dealing with the erotic” (

Smith 2006, p. 155). Smith, in all fairness, raises a valid question of how Zvelebil’s categorization applies to possession described in Indian classical literature. But that is a subject for another time. We must return to the Tiwas, for now.

The Tiwas do not get into the finer categorization and differentiation expressed by Claus and Zvelebil. For them, when they say, “Spirit possession,” they mean spirit mediumship performed by a legitimate specialist. Within the tribe, consulting a medium like Ma Muni is a normative and permissible ritual. In addition, the Tiwas view such sessions as an integral part of their indigenous religious sphere. The Tiwas’ world of the living and their world of Spirits have a religiously sanctified ontological or veridical reality. Therefore, it is a “genuine possession.” Though for the scholar, this can be a somewhat challenging reading to accept.

For us to come to terms with such a construal, I am reminded of what A.K. Ramanujan calls the “context-sensitive” epistemology of South Asian culture, quoted by Sarah Caldwell: “A ‘context-sensitive’ approach denies the ultimate truth-value of particular statements, or even their unequivocal referentiality. […]. A statement can be understood only in the full context of who says it, hears it, overhears it; under what circumstances the statement is made; and even, in India, when—the time of day, the season, the planetary influences—where, why, and innumerable other subtle contextualizing factors” (

Caldwell 1999, p. 276).

Having addressed “Spirit mediumship,” “Spirit possession, “genuine possession” and “pseudo-possession,” in the context of Ma Muni and the Tiwas, let us now look at some terms used in Sanskrit that are often associated with possession and map it to the words used by Ma Muni. In Sanskrit, one of the most popular terms used for possession is

āveśa (taking possession, entrance into), which comes from the root

ā√viś (to enter in). Derivations from the same root

ā√viś, one finds

samāveśa (penetration, absorption). The third word is

praveśana, which comes from the root

pra√viś. In this schema

āveśa has a positive connotation whereas

praveśana a negative one. Christopher Fuller explains the constructive and the damaging possession thus: “In all Indian languages, a distinction can be made between involuntary, ‘bad’ possession by a malevolent being and voluntary, ‘good’ possession by a deity” (

Fuller 1992, p. 231). While this categorization cannot be applied to all possessions, it is nevertheless an important differentiation.

However, in the case of Ma Muni, this classification does not apply. As we may recall, Ma Muni was suddenly caught by the Lord at the age of twelve, while performing her daily chores. In other words, it was involuntary. But not by malevolent beings. Since then, she calls the departed soul to communicate through her, voluntarily. Further Ma Muni’s “Bhagavān,” is a combination of Lords and the departed. Thereby, for all practical purposes, Ma Muni turns Fuller’s model on its head.

The next word in Sanskrit used for possession is derived from the root √gṛh (to grasp, seize), graha and grahaṇa. One finds grahaṇa used mostly when an inimical or involuntary take-over of a human being occurs. This is similar to Ma Muni’s use of the term dhorise, before she became the cāri bhāi pam māri for the Tiwas. But then how do we explain āhise “the coming,” of the Bhagavān? What do we make of the Bhagavān coming and placing themselves on the bamboo post, and from the post communicating through Ma Muni? How do we explain the Tiwa hermeneutics where they believe that the Bhagavān is consuming the food and alcohol, which in reality is being eaten by Ma Muni. To find possible interpretive explanation to the above questions, let us now turn to the subject of possession in tantric literature.

In the large trove of South Asian Tantra literature, one finds the term

samāveśa, or immersion, frequently in the context of

śaktipāta.

Śaktipāta is mostly given by the guru to his or her disciple and in some rare circumstances by a

siddha, an enlightened being. Jayaratha commenting on the mid-tenth to early eleventh century theologian Abhinavagupta’s

Tantrāloka states: “

Śaktipāta causes the initiate to become possessed (

āveśa); symptoms are convulsions (

ghūrṇi,

kampa), and loss of consciousness (

nidrā), the degree of possession revealed by their intensity (

tīvra). Thence the objective was immersion [

samāveśa] into the body of consciousness; to make possession, or the eradication of individuality, permanent” (

Smith 2006, p. 370).

Furthermore, Abhinavagupta in the same text also defines āveśa: “Āveśa is the submerging of the identity of the individual unenlightened mind and the consequent identification with the supreme Śambhu who is inseparable from the primordial Śakti. Thus, the tantric sense of āveśa as possession must be nuanced as interpenetration” (Ibid., p. 155). Simplistically put, the deity manifests in the practitioners’ body and she also manifests as the deity’s body. In sum, in Śakti Tantra initiatory rituals, the initiate’s body is transformed by creating a divine body or the body becomes the iṣṭa devī, the body of the “cherished goddess.”

In the context of the Tiwas’ understanding of the Mother Tantric, Ma Muni’s own interpretation of what she has to offer the tribe may be summarized thus: The arrival of the Bhagavān, where there are no distinctions made between the gods and the departed soul, is similar to āveśa as understood in Śakti Tantra. The bestowing of the title cāri bhāi pām māri, is very similar to the initiatory rites performed in Śakti Tantra. When the Bhagavān communicate through her, Ma Muni’s body is a transformed body. That is, her body is different from the body she had before the arrival of the Bhagavān and after the departure of the Bhagavān. This transformation of the body enables her to communicate with the dead. Hence, in the minds of the Tiwas, Ma Muni’s possession sessions are understood as genuine.

Tiwas also believe that Ma Muni is a specialist who is blessed, which makes her speech sacred, and thereby she is a medium. Ma Muni mediates communication with the departed. She is not mistaken with other “unblessed” people who communicate with bhūt, the malevolent entities that reside in the same larger space of the unknown, unheard, and unseen to most.

This close affiliation to Śakti Tantra compelled me to look at whether there were other possession rituals prevalent in Assam. I did not have to look too far out. Kāmākhyā, an important śākta pīṭha in Assam, reverberates with the sound of drum beats and priests chanting hymns as devotees celebrate the three-day annual Deodhani dance festival.

5. Deodhani (Sanskrit Devadhvani): The Echo of the Deity

In reference to antiquity, Kāmākhyā surpasses most of the shrines in larger India and definitely in eastern India. Kāmākhyā dates to the eighth century and continues to be one of the oldest and most revered of the early seats of goddess worship. This temple complex also epitomizes the retention of many ancient practices: “The

śākta pīṭhas in general and Kāmākhyā in particular represent a complex interaction or negotiation between main stream Brahmanical or

brāhmaṇic traditions and indigenous elements from the pre-Hindu areas of India” (

Urban 2010, p. 32). The temple is believed to be first built in 1487 C.E. and then rebuilt in the sixteenth century (

Banerji 1992, p. 147). Additionally, a unique feature of the larger temple complex of Kāmākhyā is that all the ten

mahāvidyās, or “wisdom goddesses,” have a temple dedicated to their own practices as well as a temple dedicated to Śiva and Viṣṇu respectively

6. Further, none of these goddesses are represented in imagery. They are all worshipped on sacred rocks in which it is believed the goddess resides.

Deodhani is a three days religious festival that begins on the last day of Śrāvaṇa and continues until the second day of the month Bhādrapada. According to the Gregorian calendar, these three days fall sometime in August. Deodhani is derived from the Sanskrit word

devadhvani, or the “sound of the deity. This annual festival pivots around the worship of Manasā, the serpentine goddess. The central feature of this festival is the possession of nine to fifteen people (all men) called the

deodhā. The finale is held in the

nāṭamandira portion of the Kāmākhyā temple

7. Unlike the worship of gods and goddesses being held in their respective temple, Manasā worship is performed over a sacred pitcher (made sacred ritualistically by the priest) in the

nāṭamandira, which has led some scholars to speculate that Manasā worship was borrowed from the indigenous traditions (

Mishra 2004, p. 54).

Folklore tells us that once upon a time there was king who had no offspring. He asked the goddess to bless him with a son and in return he offered his own head to her. The son was born, but the king forgot to keep his promise. One night the goddess appeared to him and reminded him of his promise. Soon after, the king severed his head and offered it to her. Thus, the king became godlike. Thereafter, he possessed a male devotee and so began the Deodhani festival.

While the Deodhani festival lasts for three days, for the deodhās it begins a month in advance. After the end of the month Āhar (mostly end of June/beginning July) and the second day of Śrāvaṇa, the deodhās start arriving in Kāmākhyā. Depending on their “calling,” they set up their prayer place either in one of the ten mahāvidyā temple or at the temple dedicated to Śiva or Viṣṇu. For almost a month, these men move within the larger Kāmākhyā temple complex in groups of five to ten, from approximately mid-day to sunrise. They cook their own meals and observe continence. They also do not engage in any professional activities. Their time is largely spent on meditating over their cherished god or goddess, chanting, and attending prayer rituals in Kāmākhyā. It is believed that during this entire month period, goddess Manasā has a hold on the deodhās (the Assamese word used by priest I interviewed was lambhā).

After the bhog, or when the blessed food is offered to the goddess Kāmākhyā approximately around 1:00 PM, the deodhās may become completely possessed. This can happen any time between 2:00 PM in the afternoon until about 3:30 AM in the morning. While being possessed, the deodhās find it almost impossible to stay inside the temple or under a roof. Experienced deodhās can withstand the possession longer than the novices. But eventually all possessed individuals run outside the temple and start screaming viciously and talking in tongues. The temple priest allows the possessed deodhā to scream for about ten to fifteen minutes, after which he sprinkles some holy water on the possessed deodhā. This eventually calms the deodhā down and he comes out of the trance state. This is a common occurrence through the entire month. Most occurrences of ferocious screaming occur between 2:00 and 3:30 AM.

On the first day of the Deodhani festival, around noon, the deodhas go through a ceremonial purification ritual called prāyaścitta, or “penance,” led by a Kāmākhyā priest. After the ritual, the deodhās wear fresh sets of clothes, offer prayers, and a handful of deodhās perform a comparatively subdued dance known as the Deodhani nās. From this day until the final day, the daily possession of the deodhas takes a rather violent turn. The deodhas when possessed not only scream ferociously, some also beat themselves with a stick, some jump maniacally, some beat their chest violently, and some thump their forehead against a wall or a pillar. Often, it leads to bleeding and/or extreme bruising. It is a disturbing sight especially for first time observers. I found that many observers, including researchers, were petrified, if not traumatized for a long time after, upon witnessing such sessions. The bloody, physical manifestations of possession often continue for about ten to fifteen minutes on the first day, until the priest sprinkles holy water.

The hallmark of the second day is marked by a procession led by the Mahādeva deodhā. One can identify the deodhās iṣṭa devtā or devī from the color of their clothes. For example, the deodhā who prays to Mahādeva wears white. He is also the ceremonial leader of the group. Purple is worn by the Kuvera deodhā, yellow is dawned by Bagalāmukhī, Bhuvaneśvarī deodhā wears light pink, Kālī deodhā wears red, and so forth. Mahādeva deodhā offers an earthen lamp to the goddess Manasā. The dancing on the second day is more pronounced compared to the first day. The violent physical manifestations of possession continue.

On the third and final day, all the deodhās get dressed. They offer prayers, and finally in a deep divine frenzy to the loud beats of powerful rhythmic drums, they enter the temple yard.

The deodhās come out in a file led by the Mahādeva deodhā. It is believed that the deodhās are temporary incarnations of their iṣṭa devā or devī. During the dance, at the end of the dance, and/or at the time of prostration before Manasā, the deodhās listen to questions asked by the devotees and offer solutions. Frequent questions I observed were related to child bearing, illness, financial problems, marriage of children, cure for an evil eye, and so forth. The devotees in turn offer he-goats, pigeons, ducks, new clothes, flowers, and/or sweets to the deodhās.

The devotees view the deodhās as loci of purification. It is believed that the possessed deity bestows the sacred seed words (bīja mantra), understood as iconic representations and sound embodiments of the gods or goddess. This enables the deodhās to have visionary and oracular abilities. Thereby, the response to devotee questions are understood as sacred, that is, directly communicated by the gods or goddesses. Devotees take all measures to adhere to the directives given by the deodhās.

At the end of the divine dancing spell, the deodhās are offered fresh blood of either a pigeon or a male goat (fresh blood is consumed by the deodhas on all three days), which has been drawn from the balī, or religious sacrifice of an animal as desired by the possessed god or goddess. Some deodhās simply bite off the head off a pigeon and drink the blood straight out of its body. Along with the blood, the deodhās drink fresh coconut water (dāb), eat a light snack, and the festival comes to an end. Finally, before leaving the Kāmākhyā complex, over the next week to ten days, the deodhās offer kumārī pūjā. Kumārī or Kumārī Devi, is the tradition of worshiping young pre-pubescent girls as manifestations of the divine female energy or Devī.

Interestingly, possessed women also arrive at Kāmākhyā during the same time that the men arrive. However, they are blessed by the temple priest and are asked to return to their village. When I asked the reason for not allowing possessed women to go through the same ritual practice, one of the priests said, “Possessed women can become very violent and hard to control. It is best they are sent back”

8. I observed a Bodo woman who was brought by her family to Kāmākhyā. People who brought her and the Kāmākhyā priest believed that she was possessed. I found her to be hysterical, hair flying, mumbling, and jumping violently. One of the priests simply looked at her, blessed her, and asked the accompanying members to take her back. I was at once reminded of Ma Muni. I could not help but wonder about the power Ma Muni yielded as a woman in this larger ritualized space of possession and the status of her oracular abilities within her tribe, the Tiwas.

The set of rituals performed in the Deodhani festival is a combination of Brahmanical ritual with more explicitly un-Brahmanical and often highly transgressive elements. For example, drinking of fresh blood is highly un-Brahmanical. Whereas practices such as the prāyaścitta ritual led by the Kāmākhyā priest, offering of a lamp to Manasā, prayers to the serpentine goddess, and kumārī pūjā are all followed within the confinements of Brahmanical rules. Therefore, Deodhani festival reflects the complex negotiation between Brahmanical and indigenous traditions that epitomizes the hybrid nature of Assamese Tantra. The cross-cultural fusion and hybridities among the indigenous, in this case the Tiwas and main stream Hindu Śākta Tantra represented by the Deodhani festival in Kāmākhyā, also demonstrates processes of Sanskritization and the Deshification respectively.

6. Conclusions

We set out with two objectives for this article: (1) Examine how possession is understood in Assam by mapping possession rituals in the Tiwa tribe and the Deodhani festival in Kāmākhyā; (2) Explore elements of hybridity in the context of Śākta Tantra in Assam.

We have witnessed through the case study of Ma Muni and the deodhās that possession is a powerful emotive state of awareness. The physical manifestations of possession can vary: Ma Muni remained calm, spoke softly, kept her eyes closed, and physically sat with her back toward the audience. The deodhas on the other hand, screamed, jumped, and physically hurt themselves. Regardless of the physical manifestation, possession in Assam serves as a bridge between the sacred and the profane, between structures of power and a culture of surrender, and as a link between rationality and the unintelligible. In addition, by seeking ritualistic contact with the dead, in the case of the Tiwas, and by letting the iṣṭa devtā or devī to take possession of the deodhās, in the annual Deodhani festival in Kāmākhyā, people in Assam continue to foster a rhetoric that validates the existence of other worlds. Contact with the other world becomes an ontological force.

A scholar must be intuitive and sensitive in using popular terms used in scholarship, lest it becomes appropriations. In the context of Ma Muni and the Deodhani festival, Ma Muni and the deodhās themselves mentioned genuine possession and fake possessions, which was mapped directly to Zvelebil’s genuine possession and pseudo-possession. But we saw how the Sanskrit binary of ā√viś and pra√viś did not map to Ma Muni’s experiences. Context-sensitive approach is best suited for such subject matter.

In the context of folk tradition and classical Hindu Tantra traditions in Assam, it is worth rethinking and redefining the boundaries between indigenous rituals and mainstream Śākta Tantra. The boundaries are blurred and both sides have borrowed heavily from each other. Indigenous practices, religious festivals, and beliefs in a plethora of exotic goddesses have continued unabated through the present. This has resulted in cross-pollination between traditional Brahmanical practices and indigenous practices, which in turn has yielded a hybrid world of Śākta Tantra rituals and practices.

As a scholar who observed many sessions of communicating with the dead among the Tiwas, witnessed and spoke to the deodhās, interviewed many devotees of Ma Muni, and talked to seekers of the deodhās, I began my journey with deep skepticism and found it challenging to accept Ma Muni or the deodhās oracular abilities. But with every passing year, after observing many sessions, I have shifted from being a skeptic to a deeply perplexed witness.