2. Forms of Traditional Religious Knowledge

Traditional religious knowledge widely incorporates traditional expressions and technical knowledge, such as verbal expression, musical expression, expression by action, and products created by traditional technical methods. It has certain attributes of a specific group and is often handed down from generation to generation. Some traditional religious expressions and traditional technical knowledge are eligible to be categorized as cultural heritage.

The issues concerning cultural heritage have attracted considerable attention from the global society. The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) defines traditional knowledge and gives an explanation about the relationship between heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional expressions [

4]. The term “traditional knowledge” used in the WIPO reports refers to the same kind of subject matter, including “tradition-based literary, artistic or scientific works; performances; inventions; scientific discoveries; designs; marks, names and symbols; undisclosed information; and all other tradition-based innovations and creations resulting from intellectual activity in the industrial, scientific, literary or artistic fields” [

4]. The categories of traditional knowledge broadly include agricultural knowledge, scientific knowledge, technical knowledge, ecological knowledge, medicinal knowledge, traditional expressions (also used in the term of “expressions of folklore”), elements of languages, and movable cultural properties [

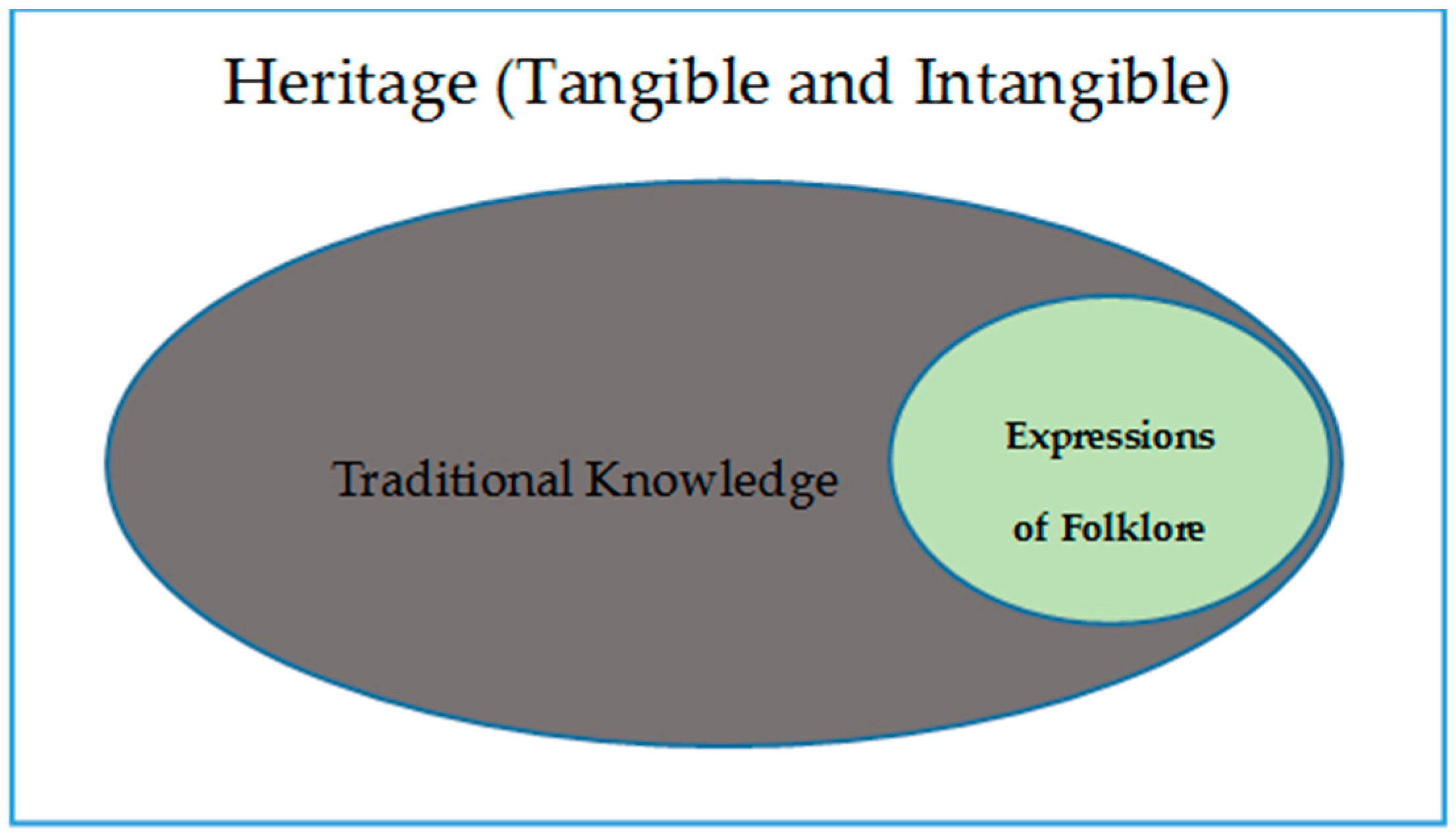

4]. From the WIPO’s perspective, traditional expression or the expression of folklore is a subset of traditional knowledge, and traditional knowledge is a subset of cultural heritage (

Figure 1). It should be noted that the aforementioned definition is not singular or exclusive. Other definitions given by scholars and international organizations indicate that the term “traditional knowledge” encompasses a wide array of meanings. However, despite difficulties regarding definition of the term “traditional knowledge,” this does not prevent the protection of the subject matter, considering that such a situation is not a new matter in the international intellectual property (IP) field. For example, the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (the Berne Convention) defines the term of “literary and artistic works” by offering a non-exhaustive enumeration of subject matter.

As shown in

Table 1, traditional religious knowledge involves various forms of traditional knowledge. For example, Chinese Daoism, China’s oldest traditional religion, has developed its unique intangible culture since the time of ancient China, including philosophy, ethics, medicine and remedies, ecological theories, healthy food recipes, and martial arts. The thought and practices of Daoism focus on explaining nature, increasing human longevity, ordering life morally, and regulating consciousness and diet [

5]. Daoism has developed a series of health cultivation practices, such as Taiji (太极), Qi Gong (气功), Wu Qin Xi (五禽戏), and Tai He Quan (太和拳), which are very popular among Chinese people. Furthermore, Daoist music has its own content and tone, with a unique rhythm, and permeated by specific religious beliefs and aesthetics. In Daoist concepts, the music is not only a section of rituals, ceremonies, and performance, but also affects human health cultivation [

6]. Daoist medical practices have made remarkable achievements in Chinese history. Plenty of prescriptions and medical academic works were developed by Daoists, which are still widely used to date [

7]. In this regard, traditional religious knowledge is considerably valuable.

4. The Scheme of Protection for Traditional Religious Knowledge in China and Challenges

China, a large and ancient country, has abundant religious cultural heritage, both tangible and intangible. The Chinese central government successively released four catalogues of the representative items of intangible cultural heritage at China’s national level, in which plenty of religious items are included [

18]. As presented in

Table 2, the religious music, folk literature, rituals or celebrations, acrobatics and athletic competition, traditional skills, traditional drama, and traditional medicine reflect distinguished Chinese traditional culture and have significant historical, literary, artistic, or scientific value. Nevertheless, traditional religious knowledge is being threatened with misappropriation and extinction. In modern society, more and more traditional religious knowledge is being used for profit, such as commercially performing religious music, and registering religious terms as trademarks. Some commercial institutions attempt to develop new techniques based on traditional religious knowledge. These activities may benefit the preservation and development of traditional religious knowledge; however, on the other hand, any misappropriation may harm the valuable knowledge and interests of the specific communities. In addition, some minority religions encounter serious difficulties in preserving their traditional knowledge due to the lack of inheritors. In view of these, it is sensible to seek protection of traditional religious knowledge under legal rules.

As a beneficiary and successor of a great ancient civilization, China has actively promoted traditional knowledge protection both at the international level and the national level. China has joined a series of important international treaties and at the same time adopted feasible approaches through domestic legislation and enforcement.

After entering into the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, China enacted the Law on Intangible Cultural Heritage (Cultural Heritage Law) [

19]. It presented China’s ambition of promoting a distinguished traditional culture and strengthening the protection and preservation of intangible cultural heritage. This is the first time the Chinese People’s Congress has made a law concerning the issue. The Cultural Heritage Law stipulates the procedures of investigating intangible cultural heritage, the ways of establishing the catalogue of the representative items of intangible cultural heritage, the obligations of the government and the representative inheritors in the inheritance and spread of the representative items, and the legal liabilities of violating this law.

From the perspective of a historical view, the achievement of this law is notable. It establishes a channel through which intangible cultural heritage, which reflects traditional culture and has significant historical, literary, artistic, or scientific value, can be recommended to be items of protection under this law. The referees may be citizens, legal persons, or other organizations. Apart from the government that has an obligation to carry out investigations into items of intangible cultural heritage, citizens, legal persons, or other organizations may conduct and participate in the investigations [

20]. Moreover, it specifies the responsible persons. Under this law, the government above the country level should adopt suitable measures to support the activities of inheriting and spreading intangible cultural heritage. The representative inheritors of intangible cultural heritage who are determined by the Chinese government have the obligations of carrying out inheritance activities, keeping the relevant physical objects and information properly, and participating in activities that benefit the public interest [

21]. In addition, the law stipulates the legal liabilities in the case of violation. Subject to this law, violating the provisions may cause administrative liability, or criminal liability.

There are still some problems that exist in the Chinese legal practice of protection. Above all, the law does not expressly stipulate the acquisition and ownership of religious property, including religious knowledge. China’s Cultural Heritage Law only provides that the Chinese government, schools, and public cultural institutions such as libraries, cultural centers, museums, and academic research institutions have their respective obligations to support protection, education, research, and spread of traditional religious knowledge. However, it does not clearly define the ownership of traditional knowledge. Other legal sources stipulating this issue are inconsistent as well. For example, religious property may be owned by the whole society, the country, Chinese religious associations, collective groups of religious believers, and so on [

22]. As a result, it is unclear as to who is eligible to claim interests generated from traditional religious knowledge and who is eligible to claim against misappropriation.

Second, China’s Cultural Heritage Law provides the administrative liability and criminal liability in the limited circumstances. For instance, the staff of the departments in charge of traditional culture and other relevant departments, who offend against the customs when conducting the investigation of intangible cultural heritage, abuse power, or practice favoritism in the work, would face administrative liability or criminal liability [

23]. The administrative liability and criminal liability will also be imposed upon the overseas organizations or individuals who illegally conduct investigations of intangible cultural heritage within China’s territory [

24]. Moreover, under this law, the civil liability is only limited to the circumstance where someone illegally damages the physical objects and premises that are a constituent part of intangible cultural heritage [

25]. However, these rules are insufficient to protect traditional religious knowledge because much of the misappropriation that damages traditional religious knowledge does not occur in the administrative process or the investigation process, but in the commercial utilization. Supposing that a pharmaceutical company used traditional religious medicine to develop new medical products but wholly ignored an appropriate compensation arrangement or representation of the contribution made by traditional religious knowledge, neither the administrative liability or civil liability could be established under China’s Cultural Heritage Law. The pharmaceutical company was not an administrative institution but a business entity, and did not damage the tangible property of traditional knowledge, either. In this regard, China’s Cultural Heritage Law cannot be invoked to claim such damages.

Unfortunately, the IP rules cannot completely solve the aforementioned difficulties, either. Although IP rules are comprehensively used to protect intangible property, they are not necessarily suitable for dealing with the issues of traditional religious knowledge. Under the IP system, the standard of eligible subject matters is quite strict such that traditional religious knowledge can hardly meet the requirements of novelty or originality. Moreover, the duration of IP rights means the exclusive rights are only granted within a limited term. Obviously, such limitation is not suitable for traditional religious knowledge.

In order to solve these problems, it is necessary to establish an integrated system that includes IP rules, sui generis and other legal rules.

First, both the IP laws and China’s Cultural Heritage Law shall expressly state the acquisition of traditional rights. The WIPO have recommended two means: acquisition automatically and acquisition through registration [

16]. In comparison, the latter facilitates right holders to provide evidence of ownership and to exploit rights. China adopts this model that requires registration as a condition for

sui generis protection.

Second, considering that traditional religious knowledge is generally perceived as a product of a collective community, the ownership of the rights over traditional religious knowledge should be granted to the concerned community rather than to individuals. As for subsequent intellectual creations, the private rights may be granted to its creators and innovators. This approach is compatible with the existing IP doctrines because the IP system need not be separately held by distinct individuals [

16]. For example, the geographic indication is a classical collective right under the trademark law. Definition of the ownership is helpful to identify the party who may take actions against certain acts and who may seek remedies or injunctions. The identified right holders should have legal personality under the laws, or be designated by the specific traditional community as the right holder in trust. Moreover, there should be sufficient connections between the identified right holder and the traditional religious knowledge in law or in practices. Some religious institutions establish independent companies that have legal personality to manage religious intangible property, which may be specified as the right holder of their traditional knowledge. The representative example is Henan Shaolin Intangible Assets Management Co., Ltd., which is wholly owned by China Songshan Shaolin Temple. On the other hand, in Chinese religious practices, the majority of religious institutions do not have legal personality. Generally, in this case, the religious associations may act on behalf of the traditional religious communities to deal with the disputes and issues in relation to religious matters.

In Shanghai Cheng Huang Jewelry Co., Ltd. v. Trademark Review and Adjudication Board of the State Administration for Industry & Commerce of China, the Daoist Association of China participated in the proceeding as a third party [

26]. This administrative proceeding was related to a dispute over the cancellation of a registered trademark “城隍” (Cheng Huang). In 1998, Shanghai Cheng Huang Jewelry Co., Ltd. (Shanghai Cheng Huang) registered “城隍” as its trademark, which was approved to use for the goods included in the fifteenth category of the prescribed classification of goods, such as precious stones, diamonds, pearls, jade, and other jewelry. In 2011, the “城隍” trademark owned by Shanghai Cheng Huang was identified as a well-known trademark. However, in Daoist concepts, “城隍” referred to gods in charge of fighting evil and bringing peace, which was included in deities of ancient Daoism since the time of ancient China. Worship of “城隍” was not only quite popular in the old time in China, Vietnam, and the Korean Peninsula, but also continues in the contemporary era in the places populated by Chinese people. The Daoists believed that the registration of the “城隍” trademark did serious harm to their religious feelings and the dignity of Daoism. Consequently, the Daoist Association of China filed an application to request the Trademark Review and Adjudication Board to make an adjudication to cancel such a registered trademark. The Trademark Review and Adjudication Board found that such registration was in violation of Article 8 of China’s Trademark Law that prohibited the use of words or devices in trademarks detrimental to the morals or customs of the society, or having other unhealthy influences. Based on its findings, the Trademark Review and Adjudication Board canceled this registered trademark. Shanghai Cheng Huang disagreed with the adjudication and brought the suit mentioned before. In this case, the Daoist Association of China acted on behalf of the Daoist communities to protect traditional Daoist Knowledge. In this regard, it is clearly a feasible approach to take actions against the misuse of traditional religious knowledge.

Third, multiple policies shall be introduced to deal with the issue concerning the expiration of rights. The duration of the right is an important method to balance IP rights and public interests. Generally, when the IP right expires, it can be used by the public without authorization. Traditional religious knowledge is passed down from generation to generation; therefore, the IP expiration rule cannot be applied appropriately to all the cases of traditional religious cases. It is sensible to categorize traditional religious knowledge into several types that different policies may be implemented on. In detail, the rights over traditional religious expressions of folklore must remain an inseparable part of the specific communities. The subsequent works created based on traditional expressions but incorporating isolated elements can be protected within the duration of protection under the copyright rules. Other forms of traditional religious knowledge, such as ecological knowledge, medicinal knowledge, religious names, and symbols may be granted traditional rights in specific terms of protection, but the term may be renewed, similar to the protection mechanism for trademarks.

Fourth, the laws should stipulate the civil liabilities in the event of misappropriating traditional religious knowledge. Misappropriation of traditional knowledge generally shows disrespect to the human dignity of the specific community. Under the civil law, the damage to human dignity establishes civil liability. Similarly, the acts of damaging the collective dignity of religions by misappropriation should establish civil liability as well. The cases of misappropriation should include disrespecting the customary rules, using a community’s traditional knowledge without just and appropriate compensation to the recognized holders of the knowledge, accessing the protected knowledge in violation of legal measures that require prior informed consent, and misrepresenting or giving misleading information in relation to the originality of religious traditional knowledge. Based on the civil liability rules, the following measures can be adopted in the case of misappropriation: claiming for equitable sharing and distribution of benefits, claiming for injunctions, and claiming for the correction of misrepresentation.