1. Introduction

One of my former Syracuse undergraduates is now an independent filmmaker in NYC [

1]. He posts regularly on Facebook about his films and his love of cinema, and whenever Alfonso Cuarón’s name or works come up, this young director scoffs. Cuarón is “all style and no substance,” he insists. I usually respond by typing a solitary exclamation mark in the comment thread, trying to signal

through style what another of his Facebook friends finally put into words: “Yea, but

what a style it is!” Director of

Little Princess,

Y tu Mama Tambien,

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkeban,

Children of Men, and

Gravity, Cuarón’s films are saturated with image. Of course all films are image-based, but in my view Cuarón works with his cinematographer—often his friend, Emmanuel Lubezki—to elicit

a painterly sensibility that often overtakes the plot in his films. Layering aesthetic obsession on top of—or in the middle of—the story he sets out to tell is precisely what my former student refers to in dismissing Cuarón as “all style.” It also is what draws me to Cuarón, because his attention to the screen as a kind of aesthesiological canvas, and the on-screen excess of what we might call “atmosphere” opens Cuarón’s films to a discussion of both affect and religion [

2]. This essay attends closely to the affective excess of

Children of Men, proceeding along five points: First, I demonstrate that the atmosphere in

Children of Men is generated and sustained primarily through a sensitive use of color. Second, I posit that this affective coloring evokes two modalities of religion, which I label nostalgic religion and emergent religion [

3]. Third, I suggest that these affective evocations are justly termed “religion” not only because they are sutured to overtly Christian names, images, and thematics, but more importantly because they signal the sacred and transcendence, respectively. Fourth, I contend that the protagonist, Theo Faron (Clive Owen), navigates these two modalities of religion not as a hero but as what Giorgio Agamben terms “whatever-being” [

4]. Finally, the structural impasse of the film’s socio-political crisis (that is, the lack of children) demonstrates the impotence of both hegemonic and counter-hegemonic political action and, I contend, signals that effective and ethical action must be linked intimately to the ongoing life of the species.

This outline of my argument does not preclude the necessity of a short précis of storyline. Children of Men is Cuarón’s 2005 film based on, but significantly changing the plot of, P. D. James’s 1992 novel of the same title. In the novel, Dr. Theo Faron is an Oxford don in a world adjusting to the imminent fact of human extinction. Men’s sperm counts have inexplicably plummeted and no one seems able to have babies any more. In this end-time situation, most people have lost interest in politics, resulting in a social infrastructure riddled with political opportunism and corruption. Theo’s cousin usurps national power, the state capitulates to dictatorship, and various revolutionary and dissident coalitions form in opposition to the state, including the Five Fishes. In the novel, Julian is not Theo’s ex-wife, but a member of the Fishes who gets pregnant by an ex-priest, Luke (and not by her husband, Rolf). Amid social upheaval, Julian gives birth to a baby boy.

In Cuarón’s film, Theo is a plodding, middle-management office drone and Julian the willful leader of the Fishes, a violent opposition group fighting the British state’s treatment of refugees (called “fugees” in the film). Theo was formerly married to Julian and they had a baby boy who died years ago in a viral epidemic. Instead of the love triangle among Julian, Rolf and Luke, then, the film galvanizes the erotic tension of lost love between Theo and Julian (Julianne Moore) to convince Theo to help the Fishes. In particular, Julian needs Theo’s political connection to his cousin, Nigel (Danny Huston), here a minister of culture and not the national dictator, in order to secure travel papers for a black woman, Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey). Theo does as he is asked, putatively for money, but soon learns that Kee is a fugee and former prostitute, and also pregnant. The Fishes take her in, but members disagree over whether to keep Kee’s baby as political leverage against the state, or to escort her to the ethereal Human Project, a rumored ship-based organization that cruises the oceans arranging shelter and protection to the few women on earth who find themselves pregnant. Theo agrees to help Kee for Julian’s sake. Julian is killed, but with the help of his friend, Jasper (Michael Caine), among others, Theo gets Kee to the coast through a fugee deportation camp at Bexhill. Kee gives birth to a baby girl and the film ends with Theo dying in a rowboat, the ship “Tomorrow” then emerging out of the fog, presumably to intercept Kee and her baby.

2. A Word on Affect and Emotion in Film

Film is a sensuous medium. It plunges viewers into sensory worlds that are drenched with noise, color, landscape, and texture; riven by the sound effects of doors, feet, punches, and sex; and attentive to the grain and emotional resonance of voice. Ironically, film’s sensuousness

heightens the challenge of representing emotion, because it is so easy to fall into cliché. Some of these representational strategies have become so familiar that they form part of the foundational “grammar” of film, such as slowly tracking-in on a character’s face to convey something like surprise, recognition, amazement, or sudden awareness; or a sudden change in weather to signal sadness after a break-up or death, with the requisite cut to raindrops slipping down a window in a close-up, or soaking the character’s silhouette in a long shot. Such filmic clichés of emotional grammar operate with the assumption that emotions are internal moods or psychological states: my anger is mine; her sadness is hers. The director and cinematographer use camera angle and movement to

perform these internal states, instead of weighing down the images with narration. In short, the strategies entail a cinematographic

externalization of presumptively interior states. The slow tracking-in externalizes a character’s “dawning awareness”, just as the rain externalizes loss or grief. Other strategies to capture emotion use camera angle and

mise-en-scène to evoke interior states of mind or mood. Filming a character persistently from a slightly high-angle might convey her insecurities, for instance, just as keeping a character isolated in the film frame emphasizes his alienation [

5]. In this essay, however, I am not interested in analyzing emotion as a mood or psychological state held inside an individual—something a person can claim or possess—but rather

affect as the a-personal and interpersonal impulses and intuitions that circulate through a community and help generate or sustain its “atmosphere”. Cuarón, in my view, is particularly adept at using film technique to put affect in circulation [

6].

The term “affect” connotes different things to different sets of scholars. My own approach stands in the line of affect theory that can be drawn from the eighteenth-century philosopher, Baruch Spinoza, up to Gilles Deleuze, from political economic theorists such as Michael Hardt and media theorists such as Patricia Clough, Zizi Papacharissi, and Tiziana Terranova, to cultural theorists such as Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Sara Ahmed, and Elizabeth Grosz, as well as the scholars associated with the Public Feelings Project (Lauren Berlant, Ann Cvetkovich, José Muñoz, Martin Manalansan, and Kathleen Stewart). This group of scholars has its own internal variation, but they all work from the premise that affect is less a feeling that occurs within a single body and is held consciously as one’s own, than a precognitive—or what I have come to term affecognitive—impulse or intensity that occurs between bodies. In this essay, I intend affect to emphasize interpersonal and situational relationships and more specifically to focus on the pulses of intensity that galvanize and hinder relationships, whether or not the relating persons are aware of them. Affects are more like our mammalian “flight or fight” response to a perceived threat than an ethical response to a difficult situation; they are moods or potentialities that are structured into the worlds we inhabit and which we use to duck and sway and barter our way through our worlds. Affects, in short, are feelings in the sense of incipient reactions, not emotions in the sense of something that needs to be channeled or controlled through ethical reflection. A good example—one I still experience in late middle age (thus demonstrating its rootedness in something other than consciousness and will)—is returning to my parents’ home and not only being treated differently than I am used to being treated in my independent and professional life in Syracuse, but also feeling and reacting and simply being differently. Old affecognitive circuits kick into gear almost as soon as the driveway comes into view, even despite my well-formed and rational resolutions “not to let this happen this time.” Affect, in sum, is raw, relational, impulsive, and circulating. If emotion is centripetal, pulling in to the psychological and spiritual core of the self, then affect is centrifugal, flinging out into the mediated flows of structured sociality.

How is affect shown in

film? How does it appear; how does it work? As I have already anticipated, affect can be thought of as the film’s mood—not the particular mood of any one character, but the murky atmosphere of the world of the film—shared amongst its characters, and also (differently) with its viewers. To use a musical analogy, affect is the “key” of a film, and also its dynamics—the volume and stylistics of execution. Cultural studies scholar Raymond Williams developed the useful notion, “structure of feeling” in his attempt to theorize the contours of social change. Past structures of feeling are easy to spot because their emergence becomes habituated and reified. Thus we know what a film from the 1940s or 1970s looks like, for instance. However, the usefulness of the term for studying affect is that technically it refers to elements of the

present that are emerging and inchoate; they still

elude fixed forms of habit, ideology or tradition. He describes it like this:

We are talking about characteristic elements of impulse, restraint, and tone; specifically affective elements of consciousness and relationships: not feeling against thought but thought as felt and feeling as thought. …We are then defining these elements as a “structure”: as a set, with specific internal relations, at once interlocking and in tension. Yet we are also defining a social experience which is still in process, often indeed not yet recognized as social but taken to be private, idiosyncratic, and even isolating, but which in analysis (though rarely otherwise) has its emergent, connecting, and dominant characteristics, indeed its specific hierarchies.

To set this kind of circulating affective structure in motion, cinematographers work with aspects of a film that viewers attend to less consciously, such as color, pacing, framing, and music. In other words, to render affect

in a film, cinematographers generate an affective circuit

between film frames, and between the film frame and the viewer. This circuit of affect between shots,

and between screen and audience resonates with Lauren Berlant when she points to the “genre of the present” as “mediated affect” [

8]. In

Children of Men, Cuarón generates affect with color, sound, and a careful attention to pacing (through montage). He also masterfully generates and diffuses affect through irrational montage, that is, moments when the camera cuts or wanders away from the protagonist(s) to linger on unexpected images of animals, food, objects, or landscape. This film is often described as “intense.” However, if Jackie Chan and Bruce Willis films are equally

violent, what produces the difference of intensity? One difference lies in the way Lubezki and Cuarón work on viewers

affecognitively, using camera movements, pacing, montage,

mise-en-scène, music, sound effects, and particularly color to render intensity as

felt and not

thought; that is, to render 2027 Britain’s

structure of feeling.

3. Sensing Religion in Children of Men: Character Critique

Affect plays a large role in

Children of Men, not only in channeling the atmosphere of panic and loss throughout a crumbling human world, but also in tracking certain fragments of hope and refuge. The film codes these fragments as differently “religious” through color, camerawork and music, and the film also underscores this

religious affective coding by looping the fragments around scattershot references to Christianity, e.g., the J-names that evoke Jesus (Jasper, Janice, and Julian), the other historically Christian names (Theo, Miriam, Marika, Luke, Patrick, Simon, and the Fishes), the loose frame of the Christmas story (an unwed mother giving “miraculous” birth in humble surroundings; see

Figure 1) and other scripture-allusive images such as roaming sheep and a two-shot that seems to echo the pieta [

9]. However, I submit that the disaggregated allusions to Christian symbols and characters would be nothing short of annoying if they were not sutured together by means of the affective resonances of color, pacing, and music. These dynamics of intensity and feeling convey both the practical impasse of the film’s apocalyptic world, and also its halting intimations of a way out—a felt transcendence of that impasse. As we will see, transcendence (which, following Raymond Williams, I place within “emergent religion”) is here not a goal or place but a felt striving or impulse to try to act beyond or—as the etymology of transcendence indicates—to attempt to climb across obvious but dead-end social options.

Figure 1.

A Note on Race.

Figure 1.

A Note on Race.

Before I get fully into my argument about affect and transcendence, it is important to clarify the film’s racial mapping since the question of race pertains to the questions I wish to raise about politics and political action.

Children of Men shows us the racism of twentieth-century imperial power in rather gruesome detail. We see a seething military resistance to “fugees” (refugees), including cages full of immigrants and unmistakable references to iconic moments of the Holocaust and the Abu Gh’raib torture scandal. These are troubling specters of racism—of how hatred for difference or for a specific “Other” can so easily tip into torture, murder, and genocide. Weaving through these disturbingly familiar dynamics of racist brutality, the protagonist, Theo Faron, functions problematically as a White Savior figure. His particular personable and moral character, cannot, I think, be reduced to his function, but nor can his filmic function be dismissed or denied. Theo clearly exemplifies the imperial dynamic of colonialism that postcolonial and feminist theorist, Gayatri Spivak summarizes as “white men saving brown women from brown men” [

10]. As we know from the recent wars of this century, brown-skinned women are frequently thrust into the ideological position of being both cause and justification for imperial and colonial military intervention that is organized primarily by white men. Theo Faron does not run a war in this film, but he is about as stereotypical a white guy as one can get: British, confident, laconic, blue eyes, and unapologetic. True to Spivak’s concern, Theo’s most basic task in the film is to save Kee, the brown-skinned and unconvincingly helpless female refugee, from the rebel group called the Fishes, which is led mostly by brown-skinned men. A white man saves a brown woman from brown men [

11]. Theo does sidestep the ideological battles between the British State and the Rebel faction—his “saving” is not an imperial function—but if you look closely at the crew of the ship,

Tomorrow, at the end of the film, they are all white men. This closing shot might be an unintended happenstance, but it remains the case that the film cannot be purged of this critique—it simply

is a film about a white man saving a brown woman from brown men, and the overlay of this plotline with the power grids of neocolonialism and neo-imperialism is likely intentional. However, I also think Theo is a different kind of white male savior. To get at Theo’s difference from the ordinary colonial and decolonial problematic of white-black relations, consider the film’s opening sequence, especially in terms of its color, sound, and pace.

The camerawork and

mise-en-scène of the film’s opening establish Theo as the protagonist and show how the precarity of his world directly affects his body. Theo is filmed as intimately connected to the world, not distinct from it. He is not shot alone, like Bruce Willis’s Frank Willis (in the opening of

Red [

12], see

Figure 2) or Sam Worthington’s Jake Sully (in the opening of

Avatar [

13]), but filmed rather in contiguity and continuity with others, a common part of the crowd and thus implicitly roped to the dynamics and detritus of its dying world. In the opening, Theo enters a café and orders coffee (

Figure 3). The throng around him is transfixed by a television news report about the violent death of a teen famous for having been the youngest person on earth. Theo attends to the news dispassionately then edges his way outside and down the sidewalk, pausing by a newspaper dispenser to take a flask from his breast pocket and pour a shot into his coffee. The news report stays with him (and us) through huge digital screens on the street buildings. Suddenly the calm shatters as a bomb explodes in the same café. The ensuing screams, sirens and high-pitched whine spilling out from the screen are the first jolts of the film’s nearly non-stop rollercoaster.

Figure 2.

Affect and Transcendence: Who is this Protagonist?

Figure 2.

Affect and Transcendence: Who is this Protagonist?

Figure 3.

The Subject as Common: Theo’s function as Example.

Figure 3.

The Subject as Common: Theo’s function as Example.

From the color of his clothes to the pervasive whine on the soundtrack that follows him—or us? or everyone?—to work long after the explosion, film viewers take in that Theo is no one special. He is just a guy. His dispassionate affect may differ from some of his citizen-peers’ more openly emotional states, but he clearly shares with them the problems of their world. This fact is conveyed through precise cinematographic strategies such as the diffuse and penetrating blue-grey palette, the fluid camerawork that enacts communality by minimizing cuts, the slightly high-angled shots that gather everyone together in mutual disempowerment, and the lingering non- or a-diegetic ringing that forms a backdrop of a pervasive and shared trauma of social violence. Together these techniques create an affective mapping of the world of the film; they are the “circulating forces” that, as Kathleen Stewart notes, “become shorthand for the state of things” [

14]. The circulating affective forces shaped by color, fluid montage, camerawork, and soundtrack constitute a shared state of the world, in which depression and disaffection (on privileged citizen bodies), as well as a desperate struggle for sustenance and raging despair (on dispossessed fugee bodies) are rampant.

Let me attend to each of these cinematographic techniques in turn. First, the diffuse grey-blue palette of the sequence renders the film’s milieu thick and grim and conveys a sludgy cold hopelessness. That color shapes and affects our mood is well known, though remarkably few studies have been made of its power, even in film. Zeno Vendler, writing on Goethe’s

Theory of Color, notes that “we live in a world of color, and no other phenomenal domain affects us more constantly and, except for music, more deeply than the display of color. Goethe is emphatic on the point that colors are ‘immediately associated with the emotions of the mind…, producing this impression in their most general elementary character, without relation to the nature and form of object on whose surface they are apparent’” [

15]. Curarón and Lubezki film nearly every scene in this gluey, grey-blue palette and thereby brilliantly structure into the fabric of the film text an affect of distance and suffocating loss. Consider how Rebecca Solnit writes about blue from a very different context but one eerily resonant with

Children of Men:

The world is blue at its edges and in its depths. This blue is the light that got lost. Light at the blue end of the spectrum does not travel the whole distance from the sun to us. It disperses among the molecules of the air, it scatters in water. …The color of that [blue] distance is the color of an emotion, the color of solitude and of desire, the color of there seen from here, the color of where you are not. And the color of where you can never go.

Blue is the cold color of loss, distance, and desire, and Cuarón and Lubezki use it to saturate the proximate. Besides inhering a chiasm of proximate distance (or receding immanence), the film’s blue-grey monochrome also provides a foundation on which the slightest swish of color pops out easily with heightened significance. Theo’s body is framed with bits of red and yellow, for instance, and function as whispering warning signs. I will return to these other colors in the next section.

A second technique of the opening sequence is the use of slightly high-angled shots that subtly position Theo alongside his fellow citizens and render them all compressed and claustrophobic bodies with quite limited power. The camera “cages” the English such that Theo’s very real freedom of being able to get coffee and go to work registers as actually (currently) not significantly more satisfying than the fugees’ being huddled together in cages to await deportation or death. The point is that Theo is very rarely filmed alone. The filmic implication is that it is not the particulars of his being or personality that enable his heroic capacity, so much as his connectivity. I will connect this connectivity to his divinity (Theo = God) in the next section.

The third important technique of the opening sequence is the persistent high-pitched ringing that lingers on the sound track, partially confirming Theo’s own psychological state, but also affectively registering the background buzz of the world’s entire awful situation. The lingering ring subtly conveys how the extraordinary trauma of street bombings has become ordinary enough to structure the physical and affective habits of the everyday. Indeed, this ringing initiates an affective refrain that returns at other moments in the film—significantly, when Julian is shot, and again in Bexhill—moments when no bomb has exploded but we hear a whine anyhow. The sustained tone thus comes to figure as a kind of quotidian PTSD—not the return of a repressed trauma in an individual so much as the breaking into consciousness of a social and shared trauma that is pervasive and relentless. Importantly for understanding the film’s affective potency, the ringing is not quite or only diegetic—that is, part of the world of the film that Theo himself can hear—but it also is not quite or only non-diegetic, or simply part of the soundtrack for us viewers. Cuarón here uses sound in a third space that generates a bridge of affect between the world of the film and the world of the audience. This third space of sound redoubles the film’s powerful affective economy by connecting viewers to the high stakes of the film’s diegetic structures of feeling.

The last technique I wish to point out is the minimal montage in this opening sequence. The fluid camera work immerses Theo in a common situation of despair by restricting camera cuts primarily to the brief shot/reverse-shot dyads of conversations. Fluid camera work is another affective refrain in the film, the most famous of which are the two extremely long and seemingly uncut sequences of Julian’s death and the uprising at Bexhill. These sequences create a panoptic suffocation, the sense that there is no escape from the conditions of this human world, a fact that is always true in a banal sense, but now unbearable in the face of apocalypse [

17]. Not only does the minimal montage generate a sense of social commonality, it also creates a steadily moving backdrop against which the pace of the film can change acutely through a shift to rapid cuts.

The cumulative effect of the formal elements of the opening sequence is to contextualize Theo’s position as simultaneously general and particular. On the one hand he appears to be the paradigm of the universal subject: a white, male, European whose name, Theo, means “god.” Thus, the formal elements of the film’s opening sequence make it difficult to demarcate Theo as the universal Man of the Humanist tradition that sought to articulate and honor an ideal set of human qualities. The film instead posits Theo not as an ideal but as a generality. He is a

general example of the human way of being-alive in 2027, not the same as everyone else—indeed in many ways stunningly privileged—but common enough. This is not the universal human of humanism, then, but one guy alongside others; Theo’s generality forms the immanent commonality of species being [

18].

In

The Coming Community, Giorgio Agamben reframes a socio-political notion of community through the ontology of “whatever-being” (

quodlibet ens) ([

4],

passim). Reminiscent of Marx’s early notion of species being, Agamben posits whatever-being as a singularity, a being with particularity but no identity—or, better, a singularity whose identity is indifferent to the specific particulars that constitute it. Agamben deftly links whatever-being to Jewish Talmudic, Christian Patristic, and medieval Christian logical texts in order to evoke a centuries-old tradition that frames discussions of life, potentiality, and ethics with “being such as it is” or “being such that it always matters” ([

4], p. 1).

1 As Agamben deploys it, whatever-being is general without being homogeneous and it is internally variegated while yet remaining “indifferent” to the particularities of that variation ([

4], p. 18). In the book’s many vignettes, Agamben delineates whatever-being through verbal images of the coming community. In other words, he gives examples. He also theorizes

example. He writes,

One concept that escapes the antinomy of the universal and the particular has long been familiar to us: the example. In any context where it exerts its force, the example is characterized by the fact that it holds for all cases of the same type, and, at the same time, it is included among these. It is one singularity among others, which, however, stands for each of them and serves for all. …Neither particular nor universal, the example is a singular object that presents itself as such, that shows its singularity.

Theo perfectly fits these characteristics of example. Too common to be particular and too specific to be universal, Theo is a singularity who stands for each human while also serving for all humans. Agamben etymologically connects the “showing” function of examples to the Greek word para-deigma (shown alongside) and the German word Bei-spiel (plays alongside). Stretching Agamben’s linguistic intentions toward my own visual intentions, I submit that Theo is shown as an example of common humanity by the way he is filmed in two-shots, three-shots, and crowds; that is, alongside other humans.

To state my argument again through the problem, Cuarón seems to put in play with Theo’s character just the kind of body that postmodern theory has critiqued for assuming a universality it cannot incarnate. However, he does so with cinematography and mise-en-scène that make Theo’s body serve as the example of a common humanity. Theo’s commonality thus matters more affecognitively than theologically; he exemplifies commonality so that he can mediate the common human striving for transcendence—for what I label “emergent religion.”

Precisely because Theo’s bodily presence and filmic function signal the whatever-being of paradigmatic commonality, the film’s opening sequence can be seen to set up a claim about citizen-subjects, namely, the ontological claim that human being is irreducible to political being and vice versa. Unlike Aristotle’s famous claim that “man is a political animal”, this film shows that humanity is both much more and much less than the usual denotations of political being. For one, it means that a citizen-subject is only a delimited section of a living-subject, and for two, that “politics”—that is, common or collective species being—implies much more than the conscripted dialectic between state sovereignty and counter-hegemonic revolution.

In reading the film as opening wide the frame of being in this way, I am arguing that its religious generativity arises in part from its recontextualizing, I would say even its transcendence of, Agamben’s arguments about

bios and

zoë. Beginning with his 1998 text,

Homo Sacer, Agamben has drawn on Aristotle and Arendt to patiently rework Foucault’s widely used notion of biopower, a rubric of social “governmentality” that counters traditional sovereign power by

using life instead of destroying it. According to Foucault, where sovereign power operates from the rule, “Let live or make die”, biopower—the system of governing populations that develops concurrently with modern nation states, industrial capitalism, and the projects of colonial imperialism—operates instead from the rule, “Make live or let die” [

19]. Agamben rivets our attention to those interstitial sites in modern societies where bodies are neither forced to live (through vaccinations, pressures to exercise and eat well, yearly physicals,

etc.) nor allowed to die (through toxic waste dumps, drug trade, homelessness,

etc.), and he calls this no-place “bare life”. As Ewa P. Ziarek stresses,

bare life, wounded, expendable, and endangered, is not the same as biological zoe, but rather the remainder of the destroyed political bios. As Agamben puts it in his critique of Hobbes’ state of nature, mere life “is not simply natural reproductive life, the zoe of the Greeks, nor bios” but rather “a zone of indistinction and continuous transition between man and beast”.

In

Children of Men, Theo does not exemplify a nostalgic appeal to simple

zoe, he does not represent the

bios of citizenship,

and he does not dwell in the indistinct zones of the refugees, the Fishes, or even the Human Project. Congruent with what we would expect of any exemplar (and of any god), Theo dovetails with and slips between all of these identities. Such a claim about Theo’s subjectivity counters critical commentary, however, since a number of scholars have emphasized how “the background is the foreground” in this film [

21]. What they mean is that the numerous hovering and hazy groups of citizens, police, refugees, and protestors, in addition to the proliferating advertisements, radio shows, graffiti and news accounts that splay out behind Theo all work together to signal what is most true and important about the year 2027, namely, the

political state of the world, where “political” here signifies either the sovereign politics of the British state (

bios acting on its own behalf) or the radical politics of the Fishes’ revolutionary hopes (

bios acting on behalf of bare life). Theo’s story is in the foreground, they note, but the

real story is the persistent background.

Such an argument not only diminishes the importance of Theo’s sacred name and function in the film, it also insists that human being is, in fact,

always subsumed within the larger importance of

bios and its relentless production of bare life. I disagree. The background and foreground are not simply opposable and reversible in the film—the politics of state and revolution waged on and amid the bodies of bare life do not simply trump and consume the more diffuse habits and grammar of the politics of common life [

22]. I would say rather that the background of the film—the politics of state and revolution—depicts a constraint on the commonality of species being, a constraint that stands obliquely to the lived commonality of Theo’s (and, differently, to Julian’s and Jasper’s and Kee’s) personal lives. That is, the common life of the species—what I am calling the larger and more diffuse mesh of political being as whatever being—forms an oblique angle to the particular life of individuals, allowing them to both dovetail and slip between the tyrannical terms of state, society, and rebellion. Something “oblique” is something peripheral, something connected indirectly or slanting, so that it is sensed affectively before cognized or recognized. As such, the relation of background to foreground in the film is not the relation of truth to its particular substrate—the truth of state or revolutionary politics, say, relative to the fodder of each citizen’s life—but rather the relation of common constraint (history, ideology, party politics) to the commonly produced “structures of feeling”, that is, the emerging shifts and contingencies of the present as it is felt and thought [

23].

The film’s focus on Theo is not a feint or mistake, then. Signifying the divine (Theo = “god”), his character evokes an example that instantiates and overreaches particularity, thereby registering common humanity, and not superlative, ideal, or universal humanity. His character exudes the immanent transcendence of shared life, not a reified transcendence that purports to escape the world’s material-affective mesh. Through Theo’s God-Man, viewers affectively sense the possibility of transcendence from the claustrophobic constraints of his dying world. However, Theo is also just a guy, one citizen doggedly getting through the days. Indeed, the film literalizes this metaphor by inserting dogs sporadically, like another refrain (

Figure 4). For instance, in the opening shot, an elderly woman at the café bar is holding a small orange and white dog; at the race track, the camera lingers on the “lost dog” flyer and then, of course, graces viewers with a quick taste of the dog-races; at Tomasz’s farm, the dogs are repeatedly friendly to Theo and Kee; at Jasper’s, the dog follows Theo outside; and finally at Bexhill we see more dogs than sheep roaming about. The cumulative effect of these canines is to visualize and materialize the chiasm God/Dog, as if to suggest that whatever divine transcendence comes out of Theo’s bodily presence, it comes not from of any superhuman qualities, but from quite ordinary actions, affects and attentiveness.

Figure 4.

A prevalence of dogs.

Figure 4.

A prevalence of dogs.

Theo, this quite human God, wanders through his eroding world with what affect theorist, Martin Manalansan, calls “disaffection” [

24]. He is a man who inhabits his world like “a pattern he finds himself already caught up in (again)” ([

14], p. 59), and thus unable to feel his agency. Such disaffection positions Theo as whatever-being, a human example ricocheting between the brutalities of state repression, on one side of him, and the explosive guerilla resistance, on the other. The intertwining of whatever-being with Theo’s particular friends and ex-relations drops him into the trajectory of saving Kee. Theo’s passive (or willful? [

25]) vapidity clears a space for viewers to angle themselves obliquely with or alongside Theo toward a different modality of human being and human politics. This obliquely angled purposiveness-without-purpose is, I contend, the very point of the film; it is an astute depiction of the way in which humans pivot around the irreducible chiasm between particular (bodily) being and political (whatever-) being, that is, between living

a life, which is always felt as immediate or present, and living as one part of a collective that is swept up in unchosen historical currents—a chiasm that, when it becomes felt, poses the question of what could possibly count as effective ethical or political action today. This pivot is what I mean by a modality of emergent religion.

For Theo, does his romantic attachment to Julian keep him in the game of saving Kee? Or is it his disgust for his cousin Nigel? Perhaps it arises from his curiosity or compassion for Kee, or his indignation at the Fishes’ attempt to politically manipulate Kee. Possibly, the answer lies in bedazzlement before the apparent miracle of her pregnancy. For while the dance of power and counter-power really cannot sustain Theo’s disaffected interest because the life inside Kee is something else altogether, something new and oblique to the terms of his world [

26]. Each of Theo’s real social connections and concerns (Julian, Nigel, compassion, indignation) piques emotions that just as quickly subside into placid practicality, but this

life inside Kee holds Theo’s attention, and pulls him into currents transversal to his expectations. Truly, Kee comes across as stupidly passive compared with Theo, and we should not hesitate to name and critique this familiar, racist dynamic. Even so, the film does siphon possibilities for action, life, and hope out of the debilitating and acutely finite state of both Theo and his world, and it does so, I contend, through specific religious modalities. The next section will show how this works.

4. Sensing Religion in Children of Men: Nostalgic and Emergent Religion

The distinction between human being and political being comes into better focus after the initial scenes at Jasper’s house. Through Theo’s friendship and history with Jasper viewers intuit how each of us lives at once as a human particularity anchored in certain non-substitutable aspects of life (Theo Faron as Jasper’s particular friend), and as a political collectivity anchored in general and substitutable aspects of life (Theo Faron is a voting, working, eating, breathing being

just like every other citizen). When he is with Jasper, Theo is three-dimensional, a man with stories and loves and relational bonds. When we see him in London, Theo is merely political being, a citizen-body like any other, privileged not to be a fugee, but still clearly living in what Lauren Berlant terms an “impasse,” unable to move forward and caught up in “the circulation of precariousness through diverse locales and bodies” ([

8], p. 199). The shots of Theo in London exemplify just this affective and collective notion of impasse—the wandering urban chaos as a certain “duration of the present” and the connection to horror and trauma that “tracks the circulation of precariousness” though housing projects, cages, and groups of the un- or under-employed.

Indeed, this circulation of precarity shows how, for many bodies, especially the disposable immigrants or refugees [

27], “political being” is a negative state, a state of extreme dispossession [

28]. However, even within such an extreme state of political being, humans still live out patterns of sedimented habit, affect and value. For example, in one London scene Theo walks off-screen and the camera lingers at a row of cages filled with refugees. We see an elderly German woman standing next to a tall, muscular black man. English audiences may not translate what the German woman is saying, though it is clear she is complaining. In fact, she is unhappy about being caged with a black man! Even at the point of deportation and certain death, this woman clings to her human

self, to what makes her unique (and rather unpleasantly so), and not what renders her common, which is her shared state of political dispossession.

This chiasm of political collectivity and human particularity is primarily tracked through Theo, and through him it is imaged clearly as impasse. That is, Theo can no more choose to be an effective political agent than he can choose to focus more narrowly on the integrity of human being. Depressed, disaffected, and saturated with the dynamics of impasse, Theo’s actions register more as effects of the blue-grey situation than as actively shaping it. This is not to say that his character does not matter, or that his specific choices are irrelevant, but rather that his character is set by a past that finds little purchase in the present, so that his choices arise out of an impotent integrity and rebound from the constraints he faces at predictable angles, like balls off the sides of a pool table.

Within the depressed and disaffected impasse of Theo’s world, religion can be sensed in two distinct ways, which I term nostalgic and emergent religion. I see nostalgic religion in connection with particular being and with a desire for past human society. Since having babies is one way to perpetuate the rituals and traditions of human existence (albeit always with generational difference), the poignant fact of infertility is the utter loss of history and future. Faced with apocalypse, the desire to repeat and amend the traditions and rituals of human culture sinks into a reactionary nostalgia [

29]. The modality of nostalgic religion refers to those filmic elements that present and linger in this impotent but comfortable and familiar past. While it would seem symmetrical to correlate emergent religion with political being, emergent religion actually bubbles up out of the pivot point of the chiasm between human being and political being. Emergent religion arises out of the social and affective landscape that forms the film’s structures of feeling, structures that are social (political and collective) but felt as private and personal (existentially particular).

Both nostalgic and emergent religious modalities in the film are expressed through warm, golden tones and through a diegetic and non-diegetic framing with classical music, especially that of John Tavener’s “Fragments of a Prayer” and “Eternity’s Sunrise.” Nostalgic religion diverges from emergent religion in being imaged also with verdant green and with pervasive markers of domesticity (soft furniture, family photos, knick-knacks, and furry pets; see

Figure 5). Nostalgic religion, in other words, hearkens back to an iconic white, heterosexual, suburban bourgeois life as its own Eden. Emergent religion, on the other hand, is imaged through sparse golden light (

Figure 6), and through specific modes of bodily vulnerability and relational attentiveness, for example by Theo’s frequent (albeit trivial) wounding by animals, by going barefoot, by loud explosions, and by his ability to attend to and care for the animals and persons right before him. Put differently, emergent religion evokes a

process and a

tendency and not a thing or a goal—it labels the striving for transcendence and not attaining it. Cuarón and Lubezki indicate it both with musical motifs—especially “Fragments of a prayer”—and also with subtle shifts of focus, such as cutting away from the psychological continuity of plot to unnecessary focus on things like dogs and cats, Theo’s feet [

30], landscapes, and skylines. These shifts of focus are moments of transition and fraught possibility; they are moments that attempt to capture something in its effervescent emergence.

Figure 5.

Nostalgic religion.

Figure 5.

Nostalgic religion.

Figure 6.

Emergent religion.

Figure 6.

Emergent religion.

The modality of nostalgic religion conjures a fertile, vibrant world. Although this world is forever lost, it is important to stress that its comforts and harmonies have fundamentally shaped Theo’s “human being.” What can be felt and accessed only nostalgically in the film’s present formed Theo’s particular sense of himself as a unique and valued person as well as his affecognitive habits of care, compassion and reciprocity. Because nostalgic religion is a modality, a way of living or experiencing, it is a loss that is not an absence but fully lived as loss. Because of this lived loss, emergent religion is not opposed to nostalgic religion but rather standing at the pivot of a chiasm between the loss of the past and the untenable character of the present. Consider the point where the two arms of a chiasm cross. Emergent religion pulses directly out of that hinge point, between human being and political being. It transmits the nostalgic sadness over a lost world (on the one hand) and (on the other hand) the disaffection, impasse, or despair for any viable action in this current world. It conveys the impotence of the typical options of staunch obedience, due process, legal reform, or even impassioned and impatient revolution. Neither arm of the chiasm is effective, nor is a dialectic between them. Something else is required. Transcending both the ontological chiasm between human being and political being, and the practical chiasm between the impossibility of going back (nostalgia) and the impossibility of going forward (through some kind of state or revolutionary action), emergent religion reframes Theo’s actions as pushing toward (but never obtaining) a way out of the chiasm’s constraints.

The modality of emergent religion, then, begins in Theo’s disaffection with the sociological dynamics around him, joins with his bodily vulnerability and learned attentiveness (to animals, to Kee) and moves toward a transcendence that is

felt as an intensity trending toward something yet unseen. From out of the nostalgic religion of domestic safety pulses an emergent religion that seeks transcendence, a way out of the impasse, without attaching to any discursive platform or practical teleology [

31].

Lauren Berlant captures something like what I mean by emergent religion when she points to “

disturbances in the atmosphere that constitute situations whose shape can only be forged by continuous reaction and transversal movement, releasing subjects from the normativity of intuition and making them available for alternative ordinaries” ([

8], p. 6). The sentence describes Theo perfectly. The muddy blue-grey atmosphere of so much of the film—and the impossibly nostalgic atmosphere of Jasper’s house—are disturbed by affective shocks that release Theo from the normativity of expected intuition and push him toward transcendence, that is, toward affective and practical alternatives.

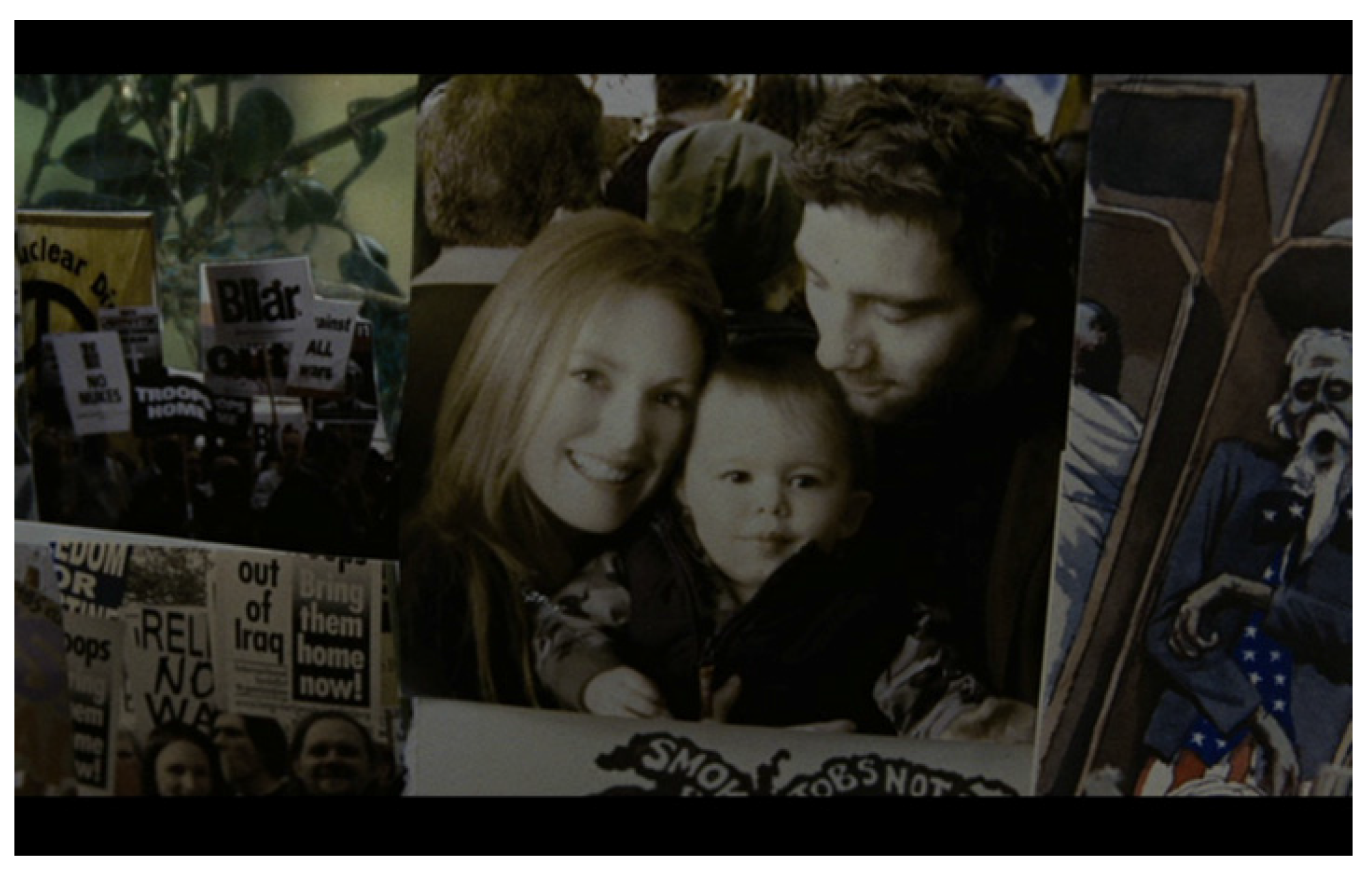

Let me make this argument by looking more closely at a few specific shots that will have to stand in for extended scene analysis, beginning with an early shot of Jasper’s house. London’s wash of blue-grey gives way to a collage of warm colors and sound. The viewer gets an almost visceral sense of relief from the tonal shift, underscored (for my age group, at least) by the gentle and familiar strains of a “Ruby Tuesday” remake and later of other classical music. The visual and aural shift frames the scene as

restorative in the sense of returning to home and home-care, and also sacred in the nostalgic sense that home is like a sanctuary. The camera enters Jasper’s home and pans across its furnishings. Its movement duplicates the bodily triangle of Jasper-Janice-Theo (

Figure 7) with the photographic triangle of Julian-Dillon-Theo (

Figure 8). It is a repetition that underscores the strength, virtue, and happiness of heteronormative family bonds, even as they effect a lost presence, since Janice is comatose and Theo’s marriage was broken up by Dillon’s death. These shots, in other words, enact the modality of nostalgic religion: they affectively mark the family as sacred (even given the form of Christian trinity), and affecognitively constellate the lost sanctity of white bourgeois, heteronormative private life as the bedrock of Western liberal democracy. A cozy home and two family triangles thus register the modality of nostalgic religion, the movement and manner of living a lost past whose future-heavy values (children) cannot be recuperated [

32].

Figure 8.

Family trio: reprise.

Figure 8.

Family trio: reprise.

Inside Jasper’s house, viewers see Theo on the sofa with his two sock-covered feet filling center screen (

Figure 9). The image draws attention to itself because it is incredibly foreshortened, using a telephoto lens to compress the space between background and foreground, so that everything behind the feet—Theo’s face, the Quietus information booklet he is reading, and the orange cat beside him—are all blurry. What does this shot convey to us? First of all, the shot is the first time we see Theo

still; before, he has been on the move in body or vehicle. Second, we have here the first moment of the film’s persistent and seemingly arbitrary attention to Theo’s vulnerable

feet. Third, it is the first moment of another persistent cinematic focus on Theo’s immediate intimacy with animals, here Jasper’s orange cat. The color orange subtly repeats the other reds and oranges, the colors of danger that amble about Theo in snatches, circulating thinly but persistently. Jasper’s body, on the other hand, is differently surrounded and suffused with green plants and warm golden light. After the shot of Theo on the sofa, the camera cuts and pans: the cut repositions the viewer behind the sofa, as if we are standing in back of Theo’s head. We see the big yellow ball of a light in center screen, and Jasper underneath it. Unlike Theo, bordered by an orange cat and red blanket and swallowed in browns and grays, Jasper seems downright aglow. His hair is illuminated and the green plants in the background encircle his body. If Theo’s

mise-en-scène signals approaching threat (again not

of Theo, not

on him, but

around him), then Jasper’s signals calm, light, hope. Theo is in trouble, and Jasper is his refuge.

Figure 9.

The vulnerabilty of feet.

Figure 9.

The vulnerabilty of feet.

In case we need this modality of nostalgic sanctuary underscored a bit more, the sequence shifts away from the intense and fluid camerawork of the film’s opening and falls into the more familiar and intimate conversational rhythm of shot/reverse-shot between Theo and Jasper. The scene ends by cutting to an exterior shot of the house, a dark box in a dark wood, with light and loud music spilling out of it. The shot is a bit of a cliché. It reminds me of similar shots of woodland cottages at night in Spirited Away and Last of the Mohicans (among others). However, it succeeds in replaying the affects circulating between Jasper and Theo in hyper-condensed form: the warmth and comfort of home, and the dark threat of the encroaching world.

Gold is the connection between nostalgic and emergent religion, but in the modality of emergent religion gold lacks green context and the affective sense of comfort and refuge (

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). We see this kind of gold when Theo is kidnapped, and the “revelatory” scenes at the barn, the school, and the birthing scene at Bexhill. The most acclaimed of these is the scene in the barn. The moment Kee “shows” her pregnancy is accompanied with the eruption of Tavener’s music and Theo’s exclamation, “Jesus Christ” [

33]. The scene is filmed classically—that is, psychologically—by emphasizing Theo’s sudden awareness of Kee’s pregnancy with a slow track in on his face. The more affective shot of the scene occurs a bit earlier than this moment that has inspired so much critical ink. The shot I have in mind occurs between two other animal shots. It is preceded by Tomasz’s dogs warmly greeting Theo in the driveway and followed by one of Tomasz’s kittens crawling up Theo’s pants at the Fishes meeting. The sandwiched shot aims a medium shot across the cows, capturing Kee in middle distance wearing her golden dress. When seen after the dogs and followed by the kitten, the presence of cows in this shot evokes just the kind of bodily vulnerability and attentiveness with which Theo has already shown to be sensitive. Indeed, positioned among these cows Kee talks at Theo about how they are manipulated by social technology for the convenience of milk production. Critics have interpreted her speech as Kee’s fear that her own milk-producing body will be abandoned to the biopolitical forces of the state, but in context with the animal scenes that buffer it, her words seem also to function as an affective pitch for the vulnerability of all life, for the way the fluids and rhythms of reproduction call out for relational attention (a call that can so easily be perverted). The “emergent religion”, here, is a pulse; it is an intensity felt

but not thought as an urge to transcend

both the state

and the revolutionary Fishes, but not toward any definite or known end.

Figure 10.

Harsh gold of emergent religion.

Figure 10.

Harsh gold of emergent religion.

Figure 11.

Emergent religion: A softer gold.

Figure 11.

Emergent religion: A softer gold.

Figure 12.

Kee “dressed” in emergent religion.

Figure 12.

Kee “dressed” in emergent religion.

The Human Project, yes, is a sort of definite goal, but it is one that holds a most ambivalent status in the film—especially for Theo. Consider, for instance, how Theo leaves the “womb” of Bexhill headfirst through the tunnel, like a newborn ready to greet the world, but then keeps his back to

The Tomorrow as he dies (

Figure 13). The closest the film gets to a practical anchoring of transcendence is not the Human Project, but the sequence often paired with the barn sequence in critical literature, namely, that of the “cease fire”, when Theo, Kee and the baby walk through the line of stunned soldiers. This sequence is clearly marked as religious by the music and, frankly, by its palpable

lack of intensity. Here is an interruption of apocalypse, a kind of

kairos when peace gurgles up and spreads over the bodies held together by the body and gaze of Kee and her baby. Supplementing the Bexhill sheep and the birth in humble quarters, this kairotic moment clearly repeats with a difference the miracle of Christ’s birth. However, this “cease fire” sequence, too, anchors the reach toward transcendence without giving it content; it indicates the stakes that

shape the necessity of emergent religion, but does not prescribe its trajectory. The soldier-sequence telescopes down from the sprawling chaos of war, rebellion, desperation, and disaffection, to the vague hope incarnated in that one, puny baby. This hope motivates and necessitates emergent religion, and it makes perfect sense for it to be articulated through Christian imagery of a miraculous birth.

Figure 13.

“Born” to the same world.

Figure 13.

“Born” to the same world.

The shot that best captures the affective structure of emergent religion, however, even though it does not include the telltale golden light, is a scene shot in pine trees outside of Jasper’s house after Theo arrives there with Kee. The scene is completely unnecessary to the film’s plot, and also much shorter than many viewers remember. Encompassing about 10s of a 30s sequence, and occurring almost exactly at the midpoint of the film, the low-angle pan across the pines is absolutely central to the film’s affective landscape (

Figure 14). At the start of the scene, the camera finds Theo out on the hill with Jasper’s dog, moving precariously in his flip-flops and dragging grounded branches to cover the car stolen from the Fishes. Already the camerawork coheres Theo’s

felt isolation and grief through a long shot that highlights his bodily vulnerability. Then Theo stops and tilts his head up at the pines, and the camera grants his POV, a panning semicircle across the arching trees. It is possible to read this brief pan as an externalization of his psychological state (blown about, confused, anxious), but to me it reads as more of a phenomenological or cosmic moment. If the sequence with the soldiers telescopes down to a puny baby, these few seconds of pine trees bending and creaking in the wind telescope out from the puniness of Theo’s mortality to the immensity of life itself. It is as if Theo senses for a split-second the hugeness of the world and of life

on the world. He senses how much exceeds him, how small he is, and how his life is swept up in unseen currents of a

more, an

ongoingness that is not inhuman and not a-human, but simply unparticular. This moment is memorable, I think, because it compresses the film’s “structure of feeling” so beautifully and so effectively.

Figure 14.

Emergent religion: affective structure.

Figure 14.

Emergent religion: affective structure.