Nurses’ Perceptions of Spirituality and Spiritual Care in Different Health Care Settings in the Netherlands

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Method

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Content, Validity and Reliability of Questionnaire

- (1)

- Demographic characteristics asked for: gender, age, worldview, educational background, and experienced life events in last three years. Next to this, the participants were asked to assess their personal spirituality with a numeral figure between one and ten.

- (2)

- Perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care: measured with the Spirituality and Spiritual Care Rating Scale (SSCRS) [19]. The SSCRS has 17 statements scored on a 5-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). This scale has four subscales: existential spirituality, religiosity, spiritual care and personal care). A high overall score indicates a more generic view of spirituality (i.e., inclusive of both religious and existential elements), and spiritual care (i.e., facilitating religious rites/rituals as well as addressing patients’ need for meaning, value, purpose, peace and creativity). The SSCRS has been used in more than 42 studies in 11 countries demonstrating consistent levels of reliability and validity with Cronbach’s Alpha scores ranging from 0.64 to 0.84 [19,20].

- (3)

- Self-assessment of spiritual care competence: measured with the Spiritual Care Competence Scale (SCCS) [21]. The SCCS contains 27 items scored on a 5-point scale ranging from “completely disagree” (1) to “completely agree” (5). This scale has six subscales: assessment and implementation of spiritual care, professional development and improving the quality of spiritual care, personal support and patient counseling, referral to professionals, attitude towards patients’ spirituality, and communication. A high overall score indicates higher levels of perceived competency. The SCCS is a valid and reliable measure of spiritual care competence. It has good homogeneity, average inter-item correlations (> 0.25) and good test-retest reliability. Cronbach’s Alpha scores range from 0.56 to 0.82 [21].

- (4)

- Evaluation one’s personal spirituality: measured with the Spiritual Attitude and Involvement List (SAIL) [22]. The SAIL consists of 26 items scored on a 6-point scale ranging from “totally not” or “never” (1) to “highly” or “often” (6). This list is arranged in three dimensions: connectedness to oneself (meaningfulness, trust, acceptance), connectedness to others and nature, and connectedness to the transcendent (transcendent experiences, spiritual activities). A high overall score indicates higher levels of spiritual attitude/involvement. Psychometric properties were tested in five samples differing in age, spiritual and religious background, and physical health. Factorial, convergent, and discriminant validity were demonstrated, and each subscale showed adequate internal consistency and test-retest reliability. Cronbach’s Alpha scores of the subscales range from 0.74 to 0.88 [22].

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

| Hospital care | Mental health care | Home care | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of nurses | 202 | 160 | 87 |

| % female | 90 | 71 | 99 |

| % younger than 31 years of age | 46 | 32 | 15 |

| % Christian | 56 | 46 | 58 |

| % atheistic/ agnostic/ ‘no faith’ | 29 | 38 | 16 |

| % with secondary vocational education | 45 | 35 | 26 |

| % with higher education | 27 | 35 | 32 |

| % with experienced life events | 58 | 61 | 54 |

| Mean numeral figure for one’s personal spirituality | 4.9 | 5.9 | 6.3 |

3.2. Characteristics of Perceptions and Competences of Spirituality and Spiritual Care

3.3. Factors and Spirituality within Health Care Sectors

| Hospital Care | Mental health Care | Home Care | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 31 y | 31–50 y | > 50 y | < 31 y | 31–50 y | > 50 y | < 31 y | 31–50 y | > 50 y | |

| SSCRS | 3.5 (0.5) | 3.5 (0.5) | 3.5 (0.6) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.9 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.4) | 3.8 (0.4) | 3.8 (0.5) |

| SCCS | 3.6 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.4) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.9 (0.5) | 4.0 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.4) | 3.9 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.6) |

| SAIL | 3.8 (0.6) | 3.9 (0.9) | 3.9 (0.6) | 3.9 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.6) | 4.2 (0.7) | 4.1 (0.7) | 4.2 (0.7) | 4.3 (0.6) |

| Personal spirituality | 4.1 (2.7) | 5.6 (2.6) | 5.0 (2.8) | 5.3 (2.7) | 5.9 (2.5) | 6.5 (2.0) | 4.9 (2.9) | 6.6 (1.9) | 6.5 (1.9) |

| Hospital Care | Mental Health Care | Home Care | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chri | Isl | Hum | Ath | Chri | Isl | Hum | Ath | Chri | Isl | Hum | Ath | |

| SSCRS | 3.6 (0.5) | 3.6 (0.3) | 3.8 (0.5) | 3.2 (0.5) | 3.8 (0.5) | 4.0 (0.4) | 3.8 (0.4) | 3.7 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.4) | 3.7 (0.3) | 3.8 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.5) |

| SCCS | 3.7 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.3) | 3.8 (0.4) | 3.5 (0.6) | 3.9 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.8 (0.5) | 3.8 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.4) | 4.2 (0.5) | 3.8 (0.8) | 3.7 (0.6) |

| SAIL | 4.0 (0.7) | 4.0 (1.2) | 3.9 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.6) | 4.2 (0.6) | 4.5 (0.8) | 3.9 (0.4) | 3.9 (0.6) | 4.3 (0.7) | 4.7 (0.4) | 4.4 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.5) |

| Personal Spirituality | 5.7 (2.5) | 4.0 (3.8) | 6.3 (2.0) | 3.1 (2.6) | 6.0 (2.4) | 7.0 (1.4) | 6.6 (1.4) | 5.3 (2.8) | 6.6 (2.0) | 7.3 (0.6) | 6.7 (1.6) | 4.4 (2.5) |

| SCCRS | SCCS | SAIL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCCS | 0.57 | - | - |

| SAIL | 0.53 | 0.46 | - |

| Personal spirituality | 0.57 | 0.46 | 0.63 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

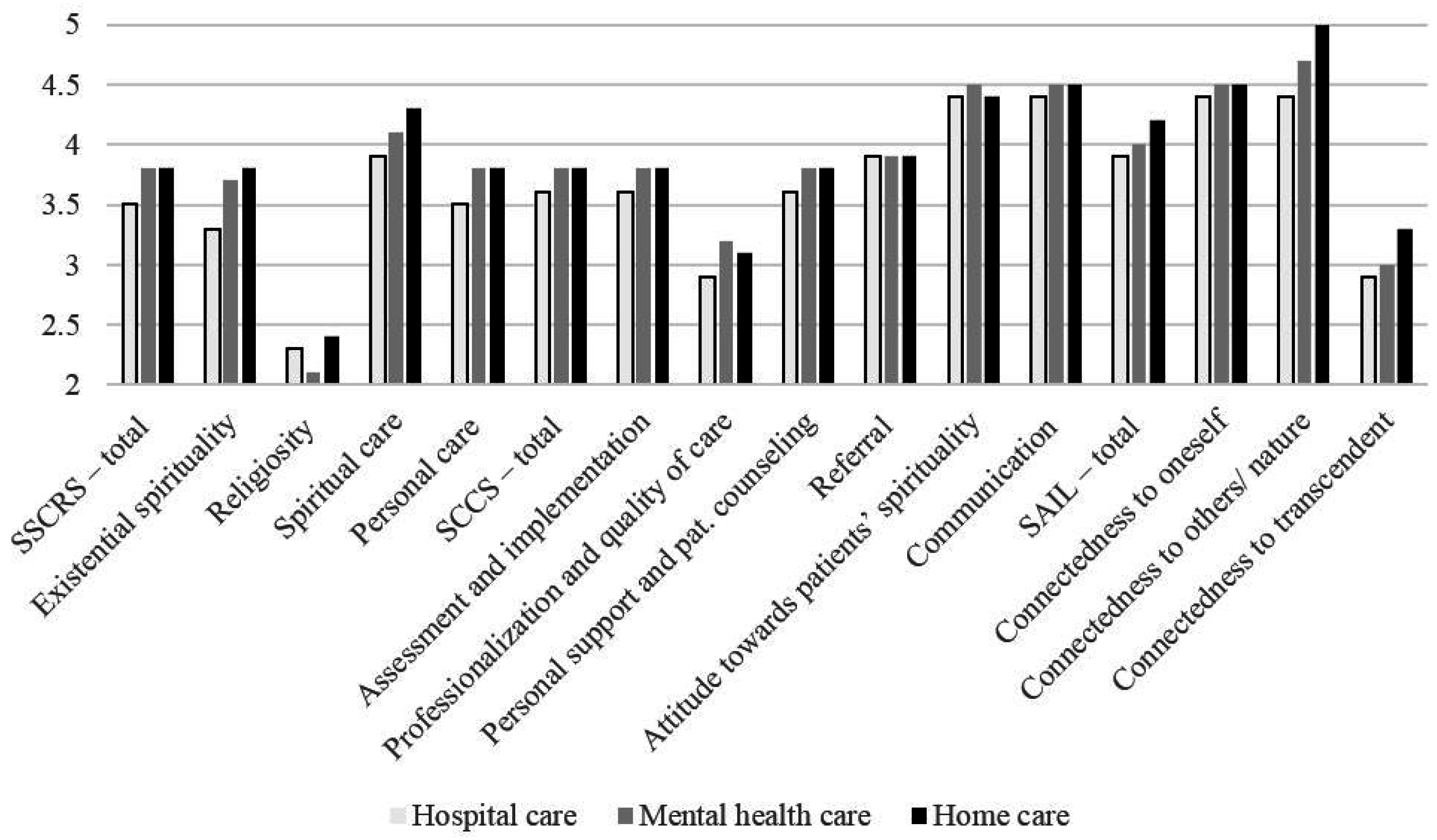

Appendix. Summary Scores of Standardized Measures (with SD): SSCRS, SCCS and SAIL with Subscales per Setting and Indication of Significance Difference between Health Care Settings

| Hospital care | Mental health care | Home care | Sign. difference | |

| SSCRS—total | 3.5 (0.5) | 3.8 (0.5) | 3.8 (0.4) | Yes |

| Existential spirituality | 3.3 (0.8) | 3.7 (0.7) | 3.8 (0.6) | Yes |

| Religiosity | 2.3 (0.7) | 2.1 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.7) | Yes |

| Spiritual care | 3.9 (0.8) | 4.1 (0.7) | 4.3 (0.7) | Yes |

| Personal care | 3.5 (0.8) | 3.8 (0.8) | 3.8 (0.7) | Yes |

| SCCS—total | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.5) | 3.8 (0.6) | Yes |

| Assessment and implementation | 3.6 (0.7) | 3.8 (0.7) | 3.8 (0.7) | No |

| Professionalization and quality of care | 2.9 (0.8) | 3.2 (0.9) | 3.1 (0.8) | Yes |

| Personal support and pat. counseling | 3.6 (0.7) | 3.8 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.6) | Yes |

| Referral | 3.9 (0.8) | 3.9 (0.8) | 3.9 (0.7) | No |

| Attitude towards patients’ spirituality | 4.4 (0.7) | 4.5 (0.6) | 4.4 (0.6) | Yes |

| Communication | 4.4 (0.6) | 4.5 (0.6) | 4.5 (0.6) | No |

| SAIL—total | 3.9 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.6) | 4.2 (0.7) | Yes |

| Connectedness to oneself | 4.4 (0.7) | 4.5 (0.6) | 4.5 (0.6) | No |

| Connectedness to others/nature | 4.4 (0.7) | 4.7 (0.6) | 5.0 (0.6) | Yes |

| Connectedness to transcendent | 2.9 (1.2) | 3.0 (1.2) | 3.3 (1.2) | No |

References

- Wilfred McSherry, and Linda Ross. “Nursing.” In Oxford Textbook of Spirituality in Health Care. Edited by Mark Cobb, Christina M. Puchalski and Bruce Rumbold. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012, pp. 70–83. [Google Scholar]

- René van Leeuwen, Lucas Tiesinga, Berrie Middel, Doeke Post, and Henk Jochemsen. “The effectiveness of an educational programme for nursing students on developing competence in the provision of spiritual care.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 17 (2008): 2768–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annemiek Schep-Akkerman, and René van Leeuwen. “Spirituele zorg: vanzelfsprekend, maar niet vanzelf (Spiritual care: obvious, but not natural).” Tijdschrift voor Verpleegkundigen 119 (2009): 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wilfred McSherry, and Steve Jamieson. “An online survey of nurses’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 20 (2011): 1757–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josephine Attar, Donia Baldacchino, and Liberato Camilleri. “Nurses’ and midwives acquisition of competency in spiritual care: A focus on education.” Nurse Education Today 34 (2014): 1460–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aru Narayanasamy, and Jan Owens. “A critical incident study of nurses’ responses to the spiritual needs of their patients.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 33 (2001): 446–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John Swinton, and Pattison Stephan. “Moving beyond clarity: Towards a thin, vague, and useful understanding of spirituality in nursing care.” Nursing Philosophy 11 (2010): 226–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiona Timmins, and Wilfred McSherry. “Spirituality: The Holy Grail of contemporary nursing practice.” Journal of Nursing Management 20 (2012): 951–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christina Puchalski, Robert Vitillio, Sharon K. Hull, and Nancy Reller. “Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus.” Journal of Palliative Medicine 7 (2014): 642–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linda Ross. “Spiritual care in nursing: An overview of the research to date.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 15 (2006): 852–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harold Koenig, Dana King, and Verna Carson. Handbook of Religion and Health, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nell Cockell, and Wilfred McSherry. “Spiritual care in nursing: An overview of published international research.” Journal of Nursing Management 20 (2012): 958–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilfred McSherry, and Steve Jamieson. “The qualitative findings from an online survey investigating nurses’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 22 (2013): 3170–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnie Weaver Battey. “Perspectives of spiritual care for managers.” Journal of Nursing Management 20 (2012): 1012–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sheryl Reimer-Kirkham, Barbara Pesut, Richard Sawatzky, Marie Cochrane, and Anne Redmond. “Discourses of spirituality and leadership in nursing: A mixed methods analysis.” Journal of Nursing Management 20 (2012): 1029–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferda Ozbasaran, Safak Ergul, Ayla Bayik Temel, Gulsah Gurol Aslan, and Ayden Coban. “Turkish nurses’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 20 (2011): 3102–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirley Ruder. “Spirituality in nursing: Nurses’ perceptions about providing spiritual care.” Home Healthcare Nurse 31 (2013): 356–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linda Ross, René van Leeuwen, Donia Baldacchino, Tove Giske, Wilfred McSherry, Aru Narayanasamy, Carmel Downes, Paul Jarvis, and Annemiek Schep-Akkerman. “Student nurses perceptions of spirituality and competence in delivering spiritual care: A European pilot study.” Nurse Education Today 34 (2014): 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilfred McSherry, Peter Draper, and Don Kendrick. “Construct validity of a rating scale designed to assess spirituality and spiritual care.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 39 (2002): 723–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud Fallahi Khoshknab, Monir Mazaheri, Sadat Maddah, and Mehdi Rahgazor. “Validation and reliability test of Persion version of the Spirituality and Spiritual Care Rating Scale (SSCRS).” Journal of Clinical Nursing 19 (2010): 2939–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- René van Leeuwen, Lucas Tiesinga, Berrie Middel, Doeke Post, and Henk Jochemsen. “The validity and reliability of an instrument to assess nursing competencies in spiritual care.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 18 (2009): 2857–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltica de Jager Meezenbroek, Machteld van den Berg, Gerwi Tuytel, Adriaan Visser, and Bert Garssen. “Het meten van spiritualiteit als universeel fenomeen: De ontwikkeling van de Spirituele attitude en interesse lijst (SAIL) (Measuring spirituality as a universel phenomenon: Development of the Spiritual attitude and involvement list (SAIL)).” Psychosociale Oncologie 14 (2006): 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kathleen Lovanio, and Meredith Wallace. “Promoting spiritual knowledge and attitudes: A student nurse education project.” Holistic Nursing Practice 21 (2007): 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ka Fai Wong, Linda Y. K. Lee, and Joseph K. L. Lee. “Hong Kong enrolled nurses’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care.” International Nursing Review 55 (2008): 333–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltica de Jager Meezenbroek, Bert Garssen, Machteld van den Berg, Gerwi Tuytel, Dirk van Dierendonck, Adriaan Visser, and Wilmar Bernardus Schaufeli. “Measuring spirituality as a universal human experience: Development of the Spiritual Attitude and Involvement List (SAIL).” Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 30 (2012): 141–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon Fai Chan. “Factors affecting nursing staff in practicing spiritual care.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 19 (2010): 2128–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lay Hwa Tiew, and Vicki Drury. “Singapore nursing students’ perceptions and attitude about spirituality and spiritual care in practice: A qualitative study.” Journal of Holistic Nursing 30 (2012): 160–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucy Rushton. “What are barriers to spiritual care in a hospital setting? ” British Journal of Nursing 23 (2014): 370–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilfred McSherry. Making Sense of Spirituality in Nursing and Health Care Practice: An Interactive Approach, 2nd ed. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Anne L. Biro. “Creating conditions for good nursing by attending to the spiritual.” Journal of Nursing Management 20 (2012): 1002–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Van Leeuwen, R.; Schep-Akkerman, A. Nurses’ Perceptions of Spirituality and Spiritual Care in Different Health Care Settings in the Netherlands. Religions 2015, 6, 1346-1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel6041346

Van Leeuwen R, Schep-Akkerman A. Nurses’ Perceptions of Spirituality and Spiritual Care in Different Health Care Settings in the Netherlands. Religions. 2015; 6(4):1346-1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel6041346

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan Leeuwen, René, and Annemiek Schep-Akkerman. 2015. "Nurses’ Perceptions of Spirituality and Spiritual Care in Different Health Care Settings in the Netherlands" Religions 6, no. 4: 1346-1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel6041346

APA StyleVan Leeuwen, R., & Schep-Akkerman, A. (2015). Nurses’ Perceptions of Spirituality and Spiritual Care in Different Health Care Settings in the Netherlands. Religions, 6(4), 1346-1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel6041346