“There Is a Higher Height in the Lord”: Music, Worship, and Communication with God

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Clear Creek M.B.C

3. African American Christianity

4. The American South

Sunday morning […] still is the most segregated time in the South. Blacks attend separate churches from whites—the National Baptist convention, not the Southern Baptist Convention; the African Methodist Episcopal Church, not the United Methodist Church; the Church of God in Christ, not the Church of God. Black churches are historic, deeply rooted in a separate black religious tradition.([1], p. 11)

5. African American Church Congregations

6. The Religious Context: The African American Baptist Service

7. A Brief Recent Overview of Clear Creek M.B.C

8. Music in Clear Creek M.B.C Services

9. Clear Creek M.B.C Morning Worship Service, 4 November 2012 [18]

- Verse

- There is a name I love to hear

- I love to sing its worth

- It sounds like music in my ear

- The sweetest name on earth

- Chorus

- Oh, how I love Jesus

- Oh, how I love Jesus

- Oh, how I love Jesus

- Because He first loved me.

10. The Text-and-Context Sermon

The more middle-class a black community becomes, the more its observances tend to conform to white norms (because it is whites who dictate the middle-class forms of behaviour). However, when dealing with features of lower-class or peasant behaviour [...] the manner of performance, especially of interactional expectations, is more characteristic of African performance practices.([19], p. 33)

- Many bulls have surrounded me,

- Strong bulls like Bashan have encircled me,

- They gape at me with their mouth, like a raging and roaring lion.

- I am poured out like water

- And my bones are out of joint.

- My heart is like wax, it has melted within me.

- My strength is dried up, like a pot shard

- And my tongue cleaves to my jaws.

- You have brought me to the dust of death.

- For dogs have surrounded me.

- The congregation of the wicked has encircled me

- They pierced my hands and my feet.

All of us have folk in our families and in our circles, that doesn’t [sic] mean us any good. An’ I don’t care what church you belong to, an’ I don’t care what denomination you belong to, there are goin’ to be some folk in the congregation and in the denomination that doesn’t mean you any good. So if you jump up and run trying to leave trouble, when you get where you goin’, you goin’ to find trouble there. That’s why Paul said “every time I desire to do good, evil is always present with me”. Sometime evil just follow you around. And if you’re not careful, sometime evil may even be in your own heart.

- You have to be careful how you judge other folk

- You have to be careful how you look at other folk

- You have to be careful what you say about other folk

- You do know that as you sow, so shall you reap, don’t you?

- You gotta give some of this back

- Oh Lord, have mercy, I’m gettin’ excited [response, “Come on pastor!”], but I’m just goin’ to talk a little bit.

- David was surrounded by folk,

- David was surrounded by folk,

- And I talkin’ about church folk,

- That didn’t mean him any good.

- You don’t hear me!.

- What makes you think that because you in church nothing bad’s gonna happen there?

- But it has always happened in God’s congregation.

- You all don’t hear what I’m sayin’!

- And so what make you think in this wicked society that we live in, we are not goin’ to have some bulls and some dogs gathered around us?

- You don’t hear what I’m sayin’!

- See, see you got to understand the mentality of a bull.

- A bull is a strong animal.

- An’ a bull can just about bully his way

- You know what a bully is, don’t you?

- A bull can just bully you around.

- An’ I grew up on a farm, and there was a big, black Bremer bull, that if you got out there too far, he was gonna come after you because it was his territory. And sometime church folk feel like this is their territory, and they don’t just necessarily want you in their territory. They will get after you.

- Lord, let me hush.

- Oooh!

- I’m just gonna stand here awhile.

- Hush now, Brunel, I’m talkin’.

- You and Eulastine now here carrying on a conversation.

- We just havin’ fun: I love ‘em both and I think they love me.

- We are caught up in a society where folk will go to church and they will lift up holy hand, and they will sing and they’ll shout, an’ they’ll pray, an’ they’ll preach and they’ll holler “Halleluia!”, and before they out the door they lyin’ on somebody.

- Oh, y’all don’t hear what I’m sayin’.

- An’ talkin’ about somebody, and you think, you wonder when they supposed to be church folk , well if you go talkin’ about what they did to you, you doin’ the same thing they did.

- So some way, if God start disciplining folk, He gonna have to discipline you too! Just because you are tellin’ the truth, don’t mean it’s right for you to spread it. Because you could cause somebody else to stumble.

- Because somebody gonna look at you and say “well if you not goin’ back, I’m not goin’ back either.”

- And the Lord said, “Woe be unto you that cause the least of these, my little ones, to stumble.”

- Surrounded by bulls and dogs.

- See, see, see you have to be ready, Barbara.

- Just because you want to treat folk nice, don’t mean folk gonna treat you nice.

- Just because you showing respect don’t mean that everybody goin’ respect you!

- But how you act isn’t predicated on how somebody treated you

- Your salvation is your salvation alone.

- Your personality is your personality.

- You’ve one soul to take care of.

- And that’s yours.

- And then you got dogs.

- Ooh!

- The wrong dogs is [sic] just nasty.

- Dogs is just flat out nasty.

- They’ll vomit,

- You know what the Scripture says.

- An’ they’ll return to their vomit.

- Now what that means is, they’ll throw up, and they’ll turn right back around and eat it up.

- That’s just flat out nasty.

- You don’t hear what I’m saying.

- But not only are dogs nasty, dogs are greedy.

- A dog will sit there, lay there with a belly-full

- And can’t eat any more

- An’ if you start up there, they’ll growl at that stuff.

- They don’t want you to have any.

- Well you got church folk who are greedy.

- You don’t hear what I’m sayin’.

- You got church folk who are just downright nasty!

- An’ they’re not nice to anybody.

- Folk barkin’ at you, “what you want?”

- Lookin’ all cross-eyed at you [makes a growling sound]

- And then, I wondered, now David, how can you say that you are surrounded by bulls and dogs?

- He said “I am surrounded, not just by bulls, but by strong bulls”.

- And then, Deacon Thompson, I looked at that Word, and I broke it open, and I found out that when David was talkin’ about bein’ surrounded by bulls, he’s prophesying Jesus’s [sic] crucifixion.

- And think about who it were that Jesus was surrounded by.

- He was surrounded by the Jewish leaders of Jerusalem.

- It was not the Romans who were out there hollerin’ “Crucify him!”

- It was the church folk!

- It’s not the folk in the street that makes us act like we act up.

- It’s us folk up in here that makes us act like that.

- See here we are trustees over God’s property, and somehow it gets to be our church so much so until we run other folk away.

- Come on here somebody, I’m almost through.

- This is not your church.

- Jesus said “Upon this rock I build my church and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.”

- An’ even though you gonna catch some hell, he, the devil can’t win.

- Ain’t no point in you runnin’, hell gonna follow you.

- But the devil can’t win, all he can do is scare you.

- Jesus was surrounded by bulls.

- You’re gonna be surrounded by bulls.

- Pere you gonna be surrounded by,

- An’ if you ain’t careful, there may even be some bulls in your family.

- An’ if you’re not even more careful, you might even be the bull.

- Y’all don’t hear what I’m sayin’.

- Whoo!

- You know they were taunting Jesus.

- They were sayin’ “if you are really are who you say you are, come down from the cross!”

- Now see that’s why the Lord didn’t let either one of us die for other folk’s salvation

- Or we would have came [sic.] down, slapped them up pretty good, went back up there and just died.

- But no, He had to show humility more than I can stand.

- Because I’m one, I’m a brother who would want to show you.

- “What you mean?

- Do you really think I can’t come down, I’ll show you.

- I can come down!”

- Y’all don’t hear what I’m sayin’.

- You know we all like to show folk what we can do.

- We might not be supposed to do it like that, but we will do it.

- It’s human nature!

- You just want folk to know, “no, I’m not scared.

- What do you mean? I’ll come down here and slap fire from you!”

- But Jesus stayed right there on that cross like He was supposed to.

- An’ then they started sayin’ stuff like “Aw, he saved others,

- But himself,

- Whoo!

- He can’t save.”

- Wow, I’m just as happy as I can be!

- By now they were taunting Jesus.

- Gambling.

- You know you got folk lookin’ at what you got.

- Gamblin’ at the casino

- Folk who won’t properly apply what they have.

- […]

- If you know God have been good to you

- Your family and your friends that are not saved

- Instead of telling them the bad things about Clear Creek, you should be telling them about the good things

- An’ when you get there [Clear Creek], instead of waiting for somebody to fire you up, you ought to be fired up for Jesus

- Not worrying about who’s looking at you

- But you oughta be ready to lift up holy hand

- Maybe you didn’t have everything you thought you should have had

- But God blessed you with something

- And you ought to tell Him “Thank you”

- Whoo!

- See I don’t know about you, but sometime on Sunday morning I can’t hardly stay in the bed

- I’m sittin’ there at my counter in the kitchen, an’ I’m readin’ and I’m prayin’

- Just waitin’ until daylight comes, so I can start getting’ ready to get here

- ‘Cause I can praise God by myself,

- But when I get where all of God’s folk are,

- An’ I see lifted up hands,

- An’ I see tear-filled eyes,

- An’ I see hallelujas

- Even though I’m goin’ through what I’m goin’ through

- I know that everything is gonna be alright, because the God we serve is just good like that

- He just good like that

- And then when I look at my little ugly self, Caroline

- An’ I see how God still love me

- I still make some mistakes, but He never cast me aside.

- I’m gonna hush…

- But He’s been good to me

- See I don’t know what God have done for you Deborah, but He’s been good to me.

- Out of all of my mishaps

- Whoo!

- See if there’s anyone here that thinks you’re not good enough to be saved

- Every now and then come talk to me

- An’ let me tell you my story,

- Let me tell you where God brought me from

- How God blessed me.

- The door is open

- And if you can’t think of anything else, you can say He died for me

- He went in the grave for me

- An’ three days later, He rose for me

- He rose for you,

- By yourself,

- Just like you are

- The door is open

- The door is open

- If there is one here

- I don’t care what condition you are

- See there is folk here

- Who are tryin’ to wait ‘til they get their lives right

- You don’t need to try to wait

- You come to Jesus just like you are

- God will accept you when it seem like there is no way

- You come to Jesus just like you are

- The door is open

- God will love you when it seem like there is no love.

- Come to Jesus

- You remember that hymn, “Just Like I Am”?

- God wlll take you just like you are

- Folk will make you think you not good enough

- Folk will make you think you not ready yet

- But God says, that’s when God says “Come as you are”

- He’s not talkin’ about your clothes

- I know you a drunkard, but come on anyhow

- I know you a smoke dope, but come on anyhow

- I know you a big liar, but come on anyhow

- “I know you a back biter”, He said, “but come on in anyhow.”

- An’ with the love of Jesus

- Jesus get in your heart, all of those habits will start to dissipate.

- The door is open

- The door is open

- Come to Jesus, just like you are

- Sometime folk will make fun of you

- They made fun of Jesus

- Talkin’ about Jesus, they made fun of Jesus

- So it’s no, it’s no different

- They gonna make fun of you

- Some of your friends or your buddies, they gonna say

- “Man, girl, I wouldn’t have gone there”

- Well, maybe not

- But you remember, God, our God says

- “If you will, then I will”

- Sometime

- And God is not gonna change His standard for us, but He will accept you just as you are.

- Come to Jesus, just like you are.

- No matter who you are, what your condition is,

- Come to Jesus!

- God bless you, we glad to have you

- [Song]: “There is so much that the Lord have done for me,

- [Spoken interjection] That’s my personal testimony!

- “When I was a sinner He set me free, Yes He did

- All of my burdens, He helped me to bear

- And all of my sorrow, He helped me to share

- And I can’t pay the Lord, but oh-oh I can tell Him, “Thank yo’ Sir”

- Through all of your sorrow you ought to tell the Lord

- Whoo!

- Thank yo’”

- I’m gonna hush, but God have been good to me

- He been good to me

- I’m only talkin’ about Goliday, but He been good to me

- Surrounded [heightened speech], but God made me a promise

- He said “I’ll never leave you, nor will I forsake you”.

- So remember no matter what you goin’ through

- The Holy Spirit, He’s right there with you through it all

- Through it all, through it all

- God bless you

- May God keep you

- God have been good to me

- So you oughta know, no matter what you goin’ through

- God is right there with you

- There might be some things that you can’t tell folk because they couldn’t deal with it

- But don’t be ashamed to admit that God have brought about a change in your life

- Don’t ever be ashamed to admit that

- Because we all need the Lord

- Don’t ever be ashamed to admit that

- Amen

- Amen.

11. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| M.B.C | Missionary Baptist Church |

| T.O.M.B. | Tallahatchie-Oxford Missionary Baptist |

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Charles Reagan Wilson. Judgement and Grace in Dixie: Southern Faith from Faulkner to Elvis. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Albert B. Cleage Jr. “A New Time Religion.” In The Black Experience in Religion. Edited by C. Eric Lincoln. New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1974, pp. 168–80. [Google Scholar]

- James H. Cone. “The sources and norms of Black theology.” In The Black Experience in Religion. Edited by C. Eric Lincoln. New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1974, pp. 110–27. [Google Scholar]

- William Jones. “A question for Black theology: Is God a White racist? ” In The Black Experience in Religion. Edited by C. Eric Lincoln. New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1974, pp. 139–55. [Google Scholar]

- Calvin B. Marshall Jr. “The Black church: Its Mission is Liberation.” In The Black Experience in Religion. Edited by C. Eric Lincoln. New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1974, pp. 157–67. [Google Scholar]

- Milton G. Sernett. “Black Religion and the question of Evangelical identity.” In The Variety of American Evangelicalism. Edited by Donald W. Dayton and Robert K. Johnston. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992, pp. 135–47. [Google Scholar]

- Mechal Sobel. Travelin’ on: The Slave Journey to an Afro-Baptist Faith. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- John B. Boles, ed. Autobiographical Reflections on Southern Religious History. Athens and London: University of Georgia Press, 2001.

- Samuel S. Hill Jr. “Southern religion and the Southern religious.” In Autobiographical Reflections on Southern Religious History. Edited by John B. Boles. Athens and London: University of Georgia Press, 2001, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Frank S. Mead, and Samuel S. Hill. Handbook of Denominations in the United States. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Randy J. Sparks. Religion in Mississippi. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Thérèse Smith. “Let the Church Sing!” Music and Worship in a Black Mississippi Community. New York and Woodbridge: University of Rochester Press and Boydell and Brewer, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- David Wills. “The Central themes of American Religious History: Pluralism, Puritanism, and the Encounter of Black and White.” In African-American Religion: Interpretive Essays in History and Culture. Edited by Timothy E. Fulop and Albert J. Raboteau. New York: Routledge, 1997, pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- C. Eric Lincoln. The Black Experience in Religion. Edited by C. Eric Lincoln. New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Richard Bauman. Story, Performance, and Event: Contextual Studies of Oral Narrative. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- “Rev. Grady McKinney (pastor, Clear Creek M.B.C., 1971–1991), in discussion with the author.” 17 November 1986.

- Therese Smith, selected excerpts from Clear Creek M.B.C. services, CD recording accompanying [12]. Original field recordings.

- Clear Creek M.B.C. Sunday Service. Directed by Clear Creek M.B.C.. 2012, DVD. [Google Scholar]

- Roger D. Abrahams. The Man-of-Words in the West Indies: Performance and the Emergence of Creole Culture. Baltimore: The John Hopkins Press, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Thé Smith. “Spirit-sung: African American Religious Music and Identity.” In Traveling Sounds: Music, Migration, and Identity in the U.S. and Beyond. Edited by Wilfried Raussert and John Miller Jones. Berlin: LIT Verlag, 2008, pp. 75–98. [Google Scholar]

- Thérèse Smith. “Preaching Power: Terror and the Good Soldier.” In Terror and Its Representations: Studies in Social History and Cultural Expression in the United States and Beyond. Edited by Larry Portis. Montpellier: Presses Universitaires de la Méditerranée, 2008, pp. 165–80. [Google Scholar]

- Jeff Todd Titon. Powerhouse for God: Speech, Chant, and Song in the Appalachian Baptist Church. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Milton J. Sernett. Afro-American Religious History: A Documentary Witness. Edited by Milton J. Sernett. Durhan: Duke University Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gerald L. Davis. I Got the Word in Me and I Can Sing It, You Know: A Study of the Performed African American Sermon. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce A. Rosenberg. The Art of the American Folk Preacher. New York: Oxford University Press, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold Van Gennep. The Rites of Passage. Translated by Monika B. Vizdan, and Gabrielle L. Coffee. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn Hinson. Fire in my Bones: Transcendence and the Holy Spirit in African American Gospel. Edited by Glenn Hinson. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Melvin Butler. “‘Now Kwe nun Senyespri’ (We Believers in the Holy Spirit): Music, Ecstasy, and Identity in Haitian Pentecostal Worship.” Black Music Research Journal 22 (2002): 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Melvin Butler. “Performing Pentecostalism: Music, Identity, and the Interplay of Jamaican and African American Styles.” In Rhythms of the Afro-Atlantic World: Rituals and Remembrances. Edited by Ifeoma Nwankwo and Mamadou Diouf. Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- James Abbington, ed. Readings in African American Church Music and Worship. Chicago: GIAQ Publications Inc. vol.12001, vol.22014.

- 1This is not, of course, to imply that Black theological production has attenuated since that time but, simply, that in terms of academic scholarship, this was a new departure that had particular impact in the 1960s and 1970s.

- 2The Baptists were the most successful denomination in converting slaves to Christianity for a variety of reasons, but not least their early evangelical efforts, and the Baptist emphasis on congregational autonomy, which had tremendous appeal for oppressed African Americans. From about 1700, it is clear that many slaveholders in the South were organising (or at least tolerating) religious instruction and places of worship for the slaves. The first specifically Black Baptist church in America was organized at Silver Bluff, across the Savannah River from Augusta, Georgia, in 1773, and other churches soon followed, most of them Baptist or Methodist. The Providence Baptist Association of Ohio, the first black Baptist group, was formed in 1836, followed by the first attempt at national organization in 1880 with the creation of the Foreign Mission Baptist Convention at Montgomery, Alabama. The American National Baptist Convention was organized in St. Louis, Missouri in 1886, the Baptist National Educational Convention was founded in the District of Columbia in 1893. All three conventions were merged into the National Baptist Convention of America in Atlanta in 1895 ([10], pp. 43–44).

- 3In 1915 the National Baptist Convention of America split into two (still separate) conventions: the National Baptist Convention of America “unincorporated” i.e., not under the laws of the District of Columbia), and the National Baptist Convention of the U.S.A., Inc., “incorporated” ([10], pp. 43–44). Of the more than twenty pages devoted to a (very brief) history of the Baptists, and description of the various Baptist associations and conventions in this text, a single two-page section is headed “Black Baptists”.

- 4Whilst broad generalisations like this are always problematic, I base these observations on 10 years of living and conducting fieldwork in the United States (1981–1991), generally attending church services weekly, and on sporadic visits since then, most recently to Atlanta, GA (April 2012) and Clear Creek/Oxford, MS (November 2012). Most of my research was conducted in Kentucky, Mississippi, and Rhode Island, but I also attended at least occasional services at African American Baptist churches in California, Connecticut, Florida, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Maine (rather rare here), New York, and Pennsylvania.

- 5It is misleading, perhaps, to imagine a homogeneous African American Baptist church (as previously explored), as Baptist churches are singularly independent and many choose not even to affiliate formally with a national organisation. Nonetheless, most African American Baptist churches share basic aspects of belief and practice.

- 6For a discussion of such sermons by a variety of preachers see, for example, [20,21,22,23,24,25], or for earlier recorded examples from Clear Creek M.B.C., see the CD accompanying [12]. It is also, of course, true that a large number of such sermons (some chanted, some not, but totalling some seven hundred) were released on “race records” between 1925 and 1941, there are also the famous recordings of the Rev. C.L. Franklin. In addition, some labels continue to release recordings of sermons by more contemporary preachers. These find a ready audience in many African American communities, and specifically dedicated African American Gospel programs continue to broadcast them.

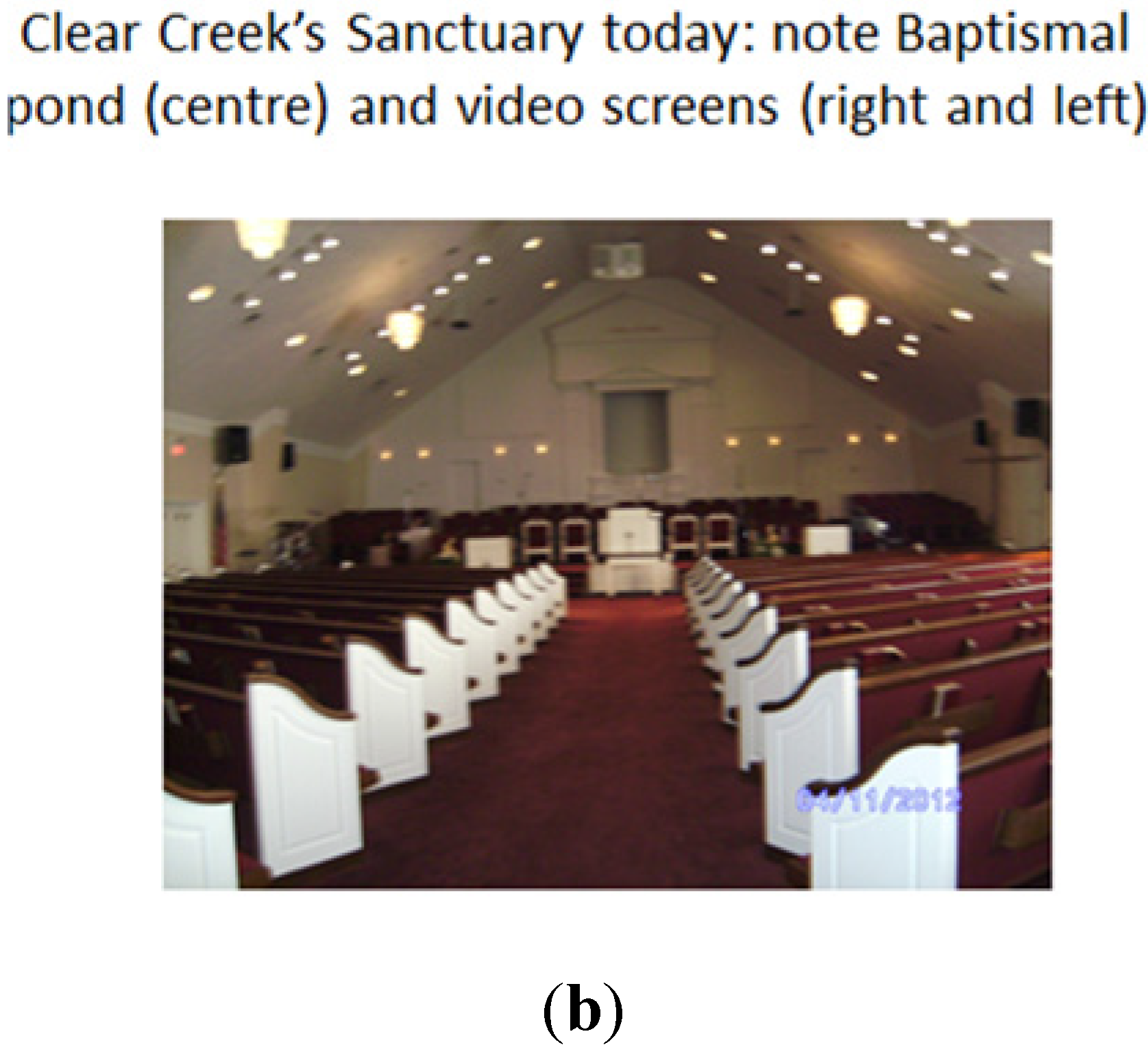

- 7Two large video screens were added on either side of the Baptismal Pool when the new church sanctuary was constructed in 2002. Because of the vastly increased size of the new sanctuary, the distance between the actors and the congregation had increased to such an extent that the screens were deemed necessary in order to integrate the congregation with the actors.

- 8While the psalm verses appeared as I have printed them on the video screens, below is how they appear in the King James Bible, which is the version that the Clear Creek membership has used since I have known them. Psalms 22, verses 12–16: 12 Many bulls have compassed me: strong bulls of Bāshan have beset me round; 13 They gaped upon me with their mouths, as a ravening and a roaring lion; 14 I am poured out like water, and all my bones are out of joint; my heart is like wax; it is melted in the midst of my bowels; 15 My strength is dried up like a potsherd; and my tongue cleaveth to my jaws; and thou hast brought me into the dust of death; 16 For dogs have compassed me; the assembly of the wicked have inclosed me; they pierced my hands and my feet.

- 9There exists a wide variety of valuable writing on this area of belief, i.e., that the Holy Spirit can be physically manifest in the Service, but detailed discussion of this literature is beyond the scope of this article. The reader is referred, however, to [23] for readings from a wide variety of perspectives and [24,25] and [27,28,29], referenced at the end of this article. For a variety of readings on African American church music and worship, the reader is additionally directed to [30], especially sections IV and VII.

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smith, T. “There Is a Higher Height in the Lord”: Music, Worship, and Communication with God. Religions 2015, 6, 543-565. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel6020543

Smith T. “There Is a Higher Height in the Lord”: Music, Worship, and Communication with God. Religions. 2015; 6(2):543-565. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel6020543

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmith, Therese. 2015. "“There Is a Higher Height in the Lord”: Music, Worship, and Communication with God" Religions 6, no. 2: 543-565. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel6020543

APA StyleSmith, T. (2015). “There Is a Higher Height in the Lord”: Music, Worship, and Communication with God. Religions, 6(2), 543-565. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel6020543