1. Introduction

Buddhism primarily addresses the human mind. Gautama, the founder of Buddhism, who lived in an area corresponding to Northern India and Nepal two and half millennia ago, sought solutions to the existential issue of suffering, especially old age, sickness, and death [

1]. Through his own questing he found deliverance from suffering, a state called enlightenment (

nirvāṇa), becoming the Buddha—literally, one who is awake ([

1], pp. 81–102).

The four noble truths are one of the Buddha’s earliest and core teachings (

Saṃyutta Nikāya, volume v, pp. 421–24). The first noble truth is

dukkha, suffering or unsatisfactoriness. The second noble truth is the cause of suffering, which is craving. Craving is closely associated with attachment, each reinforcing the other and contributing to suffering (

Majjhima Nikāya, volume i, pp. 50–51). The cessation of suffering is the third noble truth, which is enlightenment. The way leading to the cessation of suffering is the fourth noble truth. This is the noble eightfold path, consisting of right view, right motivation, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness and right concentration. With the emphasis on craving and attachment, as well as how to overcome them, the Buddha’s teachings invites consideration of how they could be relevant to the problem of addiction [

2].

This paper will consider how addictive behaviours have been seen in early Buddhism, and responses to addiction in countries with long established practice of Buddhism, before exploring how Buddhism has affected approaches to addiction recovery in North America and Europe, where Buddhism has been practised seriously for little more than half a century. Responses to addiction here include the use of mindfulness, adapting the 12 step programme and more recently developing more integrated Buddhist approaches to addiction recovery. The paper draws on both early Buddhism, as described in the Pāli canon and practised in the Theravāda, and Mahāyāna Buddhism, including Zen and Pureland.

2. Approaches to Addiction in Early Buddhism

In early Buddhism there appears to have been an awareness of some of the dangers of addictive behaviour. Principally the Buddha seems to have exhorted his followers to avoid addictive substances and behaviours by drawing attention to their unwanted consequences. There is also some evidence of simple advice being given to modify addictive behaviour.

Ethics is the foundation of Buddhist practice, being the first part of the threefold way, which consists of ethics, meditation, and wisdom (Dīgha Nikāya, volume ii, p. 91). The Buddha gave guidelines for ethical behaviour, such as the five or ten precepts. The fifth precept (of five) is abstention from intoxicants that cloud the mind. This is variously interpreted as meaning either complete abstention from intoxicating substances or moderate use that is insufficient to cloud mental faculties. The Buddha pointed out that intoxicants could lead to loss of wealth, increased quarrelling, susceptibility to disease, losing a good reputation, indecent exposure of the body and weakening of intellect (Dīgha Nikāya, volume iii, pp. 182–83). The intoxicants referred to in the early scriptures are fermented and distilled liquor, probably because alcohol was the chief intoxicant available. The Buddha also recommended avoiding gambling, citing the following dangers: the winner makes enemies, the loser grieves for his losses, loss of wealth, his word is not trusted in assemblies, he is despised by friends and associates, and he is not in demand for marriage, since he would not be seen to be able to afford to maintain a wife (Dīgha Nikāya, volume iii, p. 183).

Some of the approaches the Buddha took to the problems facing his followers could be considered to be similar to modern behavioural approaches [

3]. On one occasion the Buddha gave a programme for a king who had a tendency to overeating leading to slothfulness. The Buddha utilized the assistance of a family member. He instructed the king’s nephew at each meal to prevent the king from eating the last mouthful of food on his plate. The next meal consisted of just the amount that the king had eaten at the last meal, so that gradually the king had less and less to eat at each meal. The prince was given a verse by the Buddha to recite, if the king complained about being stopped from eating the whole plateful, reminding the king of the reasons for the programme. In time the king was reported to have lost weight and re-gained his former vitality.

In Buddhist cosmology, the hungry ghost (

preta) may be considered to be an early description of the state of addiction. The hungry ghost is one of five or six realms—traditions vary on the exact number—into which one can be reborn after death. The particular realm being the fruit of action (

karma) of the previous life. The other realms are the hell realm, the human, the animal, the heaven and the jealous anti-god (

asura) realm. The hungry ghost realm is described as a state of intense and unsatisfied craving. Hungry ghosts are referred to in most schools of Buddhism including Theravāda [

4], but are particularly well known in the West from depictions of the Tibetan wheel of life—an image that includes all six realms and is frequently found at the entrance to Tibetan temples [

5]. The hungry ghost is shown as pot-bellied with a tiny mouth. Any nourishment is difficult to take in, and when it reaches the belly it causes great pain. Contemporary writers have likened this to the state of addiction, where vain and compulsive attempts are made to assuage painful inner emptiness with external substances and objects [

6,

7].

3. Responses to Addiction in Established Buddhist Cultures

3.1. Thailand

In response to the growing heroin epidemic, Thamkrabok monastery in Thailand developed a programme to treat addicts [

8,

9]. Individuals are admitted for between 10 and 28 days. Treatment consists of herbal medicines, taking a vow, meditation, chanting, teachings on Buddhism, and work. For detoxification there are no opiates or other Western medications used. The emphasis is on purification, which is said to be assisted by the herbal medicines. Some of the herbal medicines act as an emetic, while others have a more soothing effect to help with sleep. There are herb teas and herbs that are used in a steam bath, also to promote purification. The main herbal treatment was originally developed by a nun called Saraburi. The Buddha is sometimes referred to as the Great Physician. In Buddhist countries lay people have often turned to monks and nuns for help with physical and psychological, as well as spiritual, problems. As a compassionate response members of the cenobitical community have not infrequently cultivated healing arts, especially herbal medicine. Viewing spiritual growth in terms of purification is found from early on in Buddhism. The vow,

sajja or

sacca (Pāli for true, and also meaning a solemn asseveration of the truth), is seen as a prerequisite to entering the monastery. The vow is taken in the context of a simple ceremony led by a senior monk. The person solemnly promises to abstain from all addictive substances and not to encourage anyone else to use addictive substances. The vow has also been adapted for those from a Christian or Muslim background and for those without a particular faith. Breaking the vow is seen to have adverse consequences for the individual. To underline the seriousness of the vow, participants are only allowed to enter the monastery for treatment once.

The meditation is optional, as is receiving a gāthā, a sacred set of syllables, which is intoned silently during meditation, like a mantra, and used to help at times of crisis or difficulty, such as when craving for drugs. The Buddhist teachings focus particularly on ethics, with a view to reforming the antisocial behaviour that may be associated with illicit substance use.

A cohort of 500 heroin and opium users admitted to the temple were followed up. Almost all were men. The heroin users were predominantly from Bangkok and other provincial cities. They tended to be young (mostly between 15 and 25), with about a third being unemployed and a third admitted to illegal activities to fund their habit. Two-thirds used intravenously. Abstinence at six months as validated by urine drug tests, was 20% for those from Bangkok and 30% among those from provincial cities. The opium smokers were older (80% over 30), came from rural areas and almost all were employed. They had an abstinence rate of about 50% at six months.

Joseph Westermeyer compared narcotic addicts from the neighbouring country of Laos who were treated under government auspices at the monastery (in Thailand) with those who were treated at a medical facility in Laos [

10]. Treatment at the medical facility included methadone detoxification and counselling. Participants could choose which treatment to attend. Those choosing the monastery tended to be older, and included more female and ethnic Lao (who are ethnically similar to the Thai), whereas those choosing the medical facility were more likely to be urban and educated or from a tribal group (who were mainly non-Buddhist). Follow up at six and 18 months showed no difference in abstinence rates between the two groups, although the monastery had a higher mortality rate among those over 60. The subjective rating of treatment at the monastery was positive among Lao addicts, but negative among the tribal addicts.

A qualitative study, mostly of westerners attending the monastery, suggested that participants had a favourable attitude towards the programme and felt that the induced vomiting helped with craving. There were, however, concerns about the health risks and the coercive nature of the programme [

11].

3.2. Japan

Naikan was developed in the 1940s by Yoshimoto Ishin (1916–1988) a Japanese business man who was a devout practitioner of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism [

12]. He had practised a strongly ascetic form of Shin Buddhism called

mishirabe (self-examination), which he experienced as leading to profound happiness. Shin is a form of Pureland Buddhism that emphasises faith rather than willed effort. Faith is developed from a recognition of the boundless compassion that one receives from life, and one's own inherent tendency to self-centredness. Ishin created Naikan to share his experience through a more accessible form of practice. Naikan literally means inner (

nai) looking (

kan) or introspection. It is based on three great questions: 1. What have I received from (person) X? 2. What have I given X? 3. What trouble have I caused X? The question, what trouble has X caused to me, is ignored since one is usually already aware of the answers to this question and reflecting on it is seen as unhelpful. The first person reflected on is one’s mother, followed by other family members, loved ones and friends.

There are two forms of Naikan:

Shuchu-Naikan, meaning concentrated self-observation, which is practised in a retreat setting, and

Bunsan-Naikan or dispersive self-observation, which is practised in daily life [

13]. A retreat typically consists of spending a week in solitude reflecting on the three questions. After each session of reflections, which lasts two to three hours, there is a brief interview with a guide. Initially people can struggle with the reflection, but as time goes on memories are likely to become more vivid. The effect of the reflection is said to be often cathartic. The aim of Naikan is to help people move away from self-centredness and blame, to a sense of gratitude, which leads to increased happiness.

Naikan has come to be seen as a Japanese form of psychotherapy, and although its founder was happy for it to be used in this way, he did not conceptualize it as a therapy. Rather he saw Naikan as something to be practised by anyone. As a psychotherapy, it has been used to treat alcoholism and other forms of addiction since the 1960s [

14,

15]. Gregg Krech suggests key differences between Naikan and traditional forms of psychotherapy include focussing on facts rather than feelings; reflecting on past care and support rather than hurts and mistreatment; helping the client to understand others rather than validate the client’s feelings; taking responsibility for your own behaviour and problems rather than blaming others; providing a framework for self-reflection rather than analysing and interpreting the client’s experience; and help to increase client’s appreciation for life rather than self-esteem [

16]. There are now over 40 centres delivering Naikan in Japan, with some centres in Europe and the United States.

Takemoto and colleagues reported a follow-up study of 129 patients with alcoholism who were treated with Naikan [

17]. They found a 53% abstinence rate from alcohol at 6 months, and 49% abstinent at one year.

4. Mindfulness

4.1. Mindfulness in Early Buddhism

Mindfulness is central to the practice of Buddhism (

Dhammapada, verses 21–32), [

18]. It is included in many of the important formulations of the path, such as the noble eightfold path (

Majjhima Nikāya, iii, pp. 71–76) and the seven factors of enlightenment (

Majjhima Nikāya, volume iii, p. 85). The principal Pāli word that is translated as mindfulness is

sati, which is often linked to a related term,

sampajāna [

19].

Sati refers to paying attention to experience in the present moment. It is derived from the verb to remember, and so has a connotation of recollecting oneself.

Sampajāna is clearly knowing, which in this context refers to understanding the data that is gathered through paying attention to present experience. In particular it is understanding that phenomena are impermanent, which gives rise to wisdom.

Typically mindfulness is cultivated through paying attention to bodily sensations; the hedonic colouring of experience (

vedanā)—that is, whether it is pleasant, unpleasant or neutral; to emotions and volitions; and through applying different frameworks (

dhammas), such as the four noble truths, to contemplate one’s experience. It can also be directed to broader aspects of experience such the external environment and other people [

20] Mindfulness can be developed at any time, such as when walking, eating or excreting (

Majjhima Nikāya, volume iii, p. 90), or in a more focussed way during meditation, especially meditating on the breath (the mindfulness of breathing,

Majjhima Nikāya, volume iii, pp. 78–88). The aim is to gradually build up a more and more continuous awareness of your experience. This sustained awareness is used to train the mind, especially through which mind states are cultivated and which let go of, and to see clearly the nature of experience in order to liberate the mind from misunderstandings (

avijjā or spiritual ignorance) that lead to suffering.

4.2. Mindfulness as a Therapeutic Modality

Jon Kabat-Zinn first developed the use of mindfulness as a therapeutic modality [

21]. He set up a stress clinic in Massachusetts in the late 1970s where he took people who were suffering from chronic pain that orthodox medicine could do nothing more for, as well as people who were stressed or anxious. He provided an eight week course that taught mindful meditation such as the body scan and mindfulness of breath and body, mindful movements based on simple yoga exercises and informal mindfulness practices, which involved bringing mindful attention to daily activities such as eating, washing up or walking. He found that people with chronic pain benefitted from the course [

22]. A four-year follow-up showed that gains were maintained, especially if people continued to practise mindfulness—even if this was only the informal practices [

23].

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR)—the course developed by Kabat-Zinn—has since been used and adapted for a range of conditions and populations. One of the most significant developments has been mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression (MBCT) [

24]. Segal and colleagues were tasked with developing a maintenance form of cognitive therapy that could keep people well who had had previous episodes of depression, given that depression has a high relapse rate. They became interested in Kabat-Zinn’s work. Initially they intended to include some mindfulness into a standard cognitive therapy programme, but ended up with a mindfulness course, very similar to MBSR, but including some elements of cognitive therapy and focussed on issues associated with depression such as rumination. They conducted a three-centre randomised controlled trial that showed the likelihood of relapse was halved in those who had had three or more previous episodes of depression [

25]. Their work has been highly influential in further developing the therapeutic use of mindfulness in the UK and elsewhere.

4.3. Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention for Addiction

The cultivation of increased attention through mindfulness suggested itself as a possible adjunct to relapse prevention work in addiction [

2]. Given that addiction, like depression, is associated with a high relapse rate, the emphasis on relapse prevention in MBCT offered a possible approach to preventing relapse into addictive behaviour. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention (MBRP) is an adaptation of MBSR and MBCT for preventing relapse in addiction [

26]. Like the other mindfulness-based approaches, MBRP includes formal and informal mindfulness practices. As in traditional (CBT based) relapse prevention for addiction, there is training in understanding the relapse process including high-risk situations and substance-related cognitions. However, the emphasis is on using mindfulness to change the relationship to cognitions rather than change the content, and to learn to stay with experience, such as craving or unpleasant emotions.

Although mindfulness was initially seen as a possible tool to help prevent relapse, with its usefulness in helping a wide range of emotional difficulties and improving well-being, it is increasingly being viewed as an adjunct to support a patient’s overall journey of recovery. As a recognition of this, some now prefer to call the course mindfulness-based addiction recovery (MBAR) [

27].

A review by Zgierska in 2009 of seven randomised controlled trials of mindfulness for addiction indicated that five showed improved substance use and two were similar to controls [

28]. As with other psychosocial studies, generally mindfulness did better than standard care, but similar to outcomes when compared with another structured psychosocial intervention. There was a high patient satisfaction. Between 50 and 80% of participants continued to practise mindfulness after the programme had finished. There were improvements in some other outcomes such as motivation to avoid HIV infection, self-identity, and overall psychological and social adjustment.

A subsequent pilot efficacy trial of MBRP used as an aftercare following intensive substance misuse treatment showed increased acceptance and reduced substance use and craving, especially in response to depression [

29,

30]. A randomized trial comparing standard relapse prevention to MBRP in part of a residential addiction treatment programme for women offenders found that MBRP resulted in fewer drug using days and fewer medical and legal problems [

31].

An Australian study called Parents under Pressure taught mindfulness to parents on a methadone programme [

32]. The project aimed to help parents maintain their focus on the children and to be able to regulate their emotions. The randomised controlled trial showed that those on the parenting intervention with mindfulness improved their parenting, their children’s behaviour improved and they reduced the dose of methadone that they were taking.

Mindfulness has also been used to help with smoking cessation. A randomized controlled trial comparing a mindfulness programme with standard care, which included nicotine replacement, found that those in the mindfulness group had significantly higher abstinence rates at six months [

33]. Of note in this study, the population taking part in the trial came from a low socioeconomic group.

4.4. Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

Mindfulness is a component of both DBT and ACT. Marsha Linehan developed DBT for the treatment of borderline personality disorder [

34]. This is a multi-component skills training treatment including both cognitive-behavioural therapy and mindfulness. Drawing on her background in a Zen tradition, Linehan used mindfulness particularly to help with accepting emotions. DBT has been adapted for use with substance misuse with promising results in initial trials [

35].

ACT, like DBT and the mindfulness-based approaches such as MBRP, is another third wave cognitive-behavioural therapy. Unlike DBT and MBRP it does not have its roots in the Buddhist tradition, but has been developed from relational frames theory [

36]. Key aspects of ACT include identifying and acting upon important values for an individual—commitment—and facing up to the difficulties that show up when trying to follow valued actions—acceptance. In practice the acceptance part of ACT turns out to be very similar to mindfulness as used in mindfulness-based therapies [

37]. As a consequence, ACT therapists often techniques taken from other mindfulness-based approaches [

38]. ACT has been adapted for use in addiction [

39], with a small evidence base for its use [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44].

4.5. Mode of Action of Mindfulness

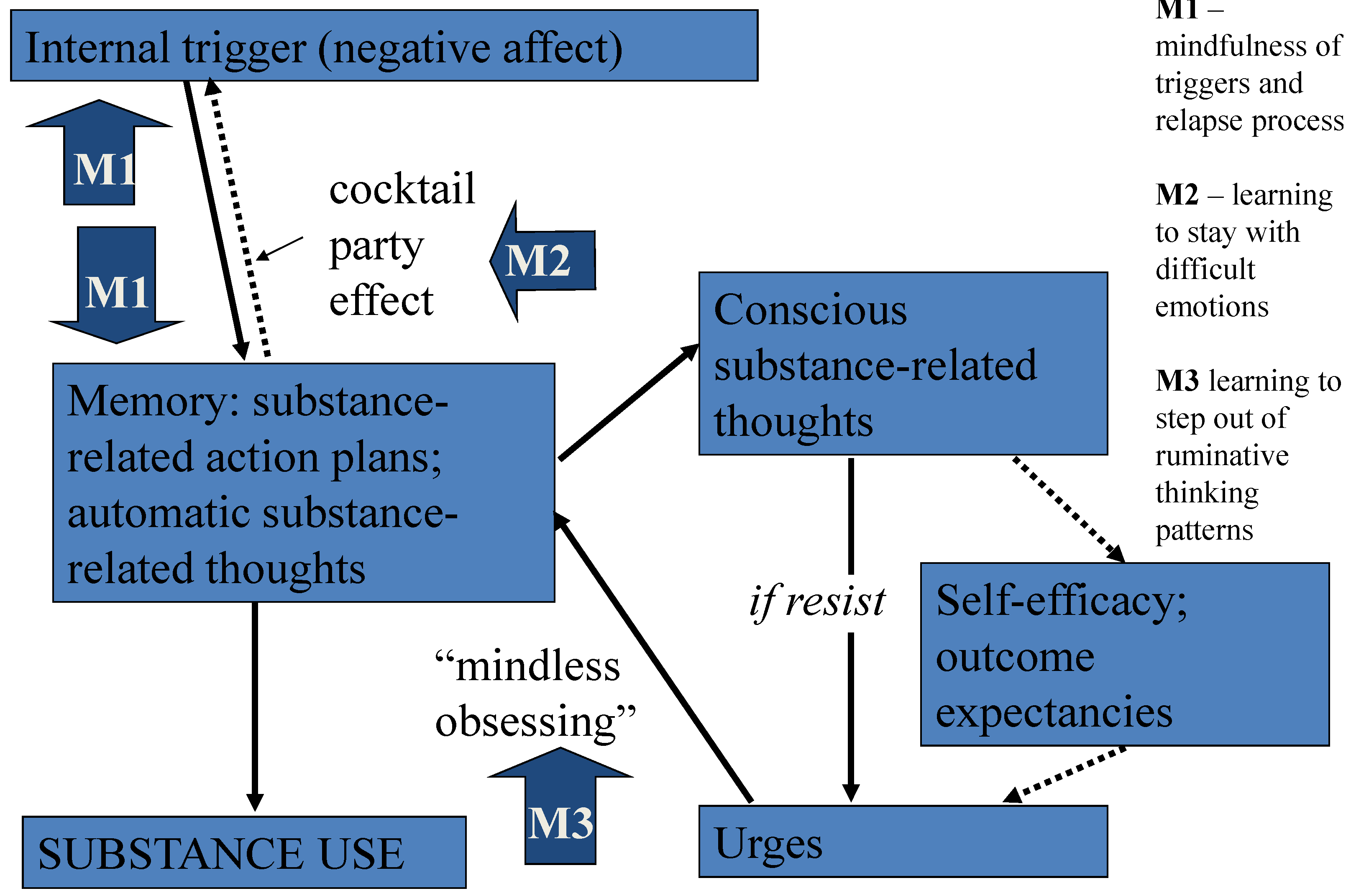

The mechanism of mindfulness may be understood through an information processing analysis. According to this model, illustrated in

Figure 1, negative affect is a key trigger to relapse into addictive behaviour. Substance use may be used to temporarily escape from negative affect. This is thought to lead to a conditioned association whereby passing unpleasant emotions more easily catch attention (the cocktail party effect), and negative affect becomes bound to substance-related action plans in memory [

45]. The cocktail party effect is a description of the phenomenon of picking up one’s name from background noise [

46]. Relapse may proceed by a pre-conscious or automatic route and through a more conscious course. In the former negative affect activates automatic planning and thinking from memory, which in turn leads to substance use. With the latter, a trigger stimulates thoughts from memory about substance use that become conscious. Resisting these thoughts—because the individual is trying not to use—is likely to lead to urges or craving. This in turn stimulates more thoughts about using substances from memory, which can create a vicious cycle, sometimes referred to as “mindless obsessing”. The urges are likely to be greater if confidence in handling the situation is reduced (low self-efficacy), and if the person believes substance use will help the situation (high outcome expectancy).

Mindfulness may help firstly by learning to develop awareness of the automatic processes, so that one is less likely to be hijacked by them (M1 on

Figure 1). Secondly mindfulness can assist learning to stay with and accept difficulties, rather than block them out. Learning to be with difficult emotions can help to break the link between negative affect and relapse-related thoughts and plans (M2). Learning to be with urges and to step out of compulsive thinking can help to reduce the likelihood of relapse through “mindless obsessing” (M3). Thus mindfulness may be able to both sensitize to automatic processes and desensitize to negative emotions and thoughts.

Figure 1.

Relapse process and potential modification by mindfulness.

Figure 1.

Relapse process and potential modification by mindfulness.

At a neurobiological level, mindfulness may help prevent relapse into addiction through top-down and bottom-up processes [

47]. Top-down processes include increasing executive functioning, and improving attention, cognitive and emotion regulation. Bottom-up processes include reducing reactivity to stressors and craving cues. For example, mindfulness meditation leads to a decoupling of insula-vmPFC (ventero-medial pre-frontal cortex) and a coupling of insula-dlPFC (dorso-lateral pre-frontal cortex) [

48]. Extended meditation is associated with thickening of the right insular and somatosensory cortices. This lateralisation suggests a shift away from self-referential thinking (as in rumination) to be able to be more objective and more easily accepting. At a hemodynamic level, mindfulness may lead to less heart-rate reactivity, reducing stress responses (a bottom-up process). Mindful practice also appears to increase high-frequency heart-rate variability (a top-down process), which provides a more adaptive regulatory response to stress [

49,

50].

4.6. Mindfulness for Dual Diagnosis

Mindfulness appears to help depression, anxiety, stress, poor emotional regulation and avoidance coping. Both addiction and some mental health disorders, such as depression, have in common stress vulnerability and problematic rumination. Both may be helped by the attention training of mindfulness and learning acceptance. It has been suggested then that mindfulness may be of particular use where there are co-morbid mental health problems with substance misuse [

51]. Some of the mindfulness trials, especially with DBT and ACT, have been with co-morbid populations [

44,

52,

53].

5. Buddhism and the Twelve Steps

A number of writers and teachers have sought to adapt the twelve step approach for Buddhists or infuse the twelve steps with teachings and practices from the Buddhist tradition. Typically these authors have been in recovery from drug or alcohol addiction. For some their involvement with the twelve steps has led to seeking further spiritual support and sustenance [

54,

55]. For others, recovering within the twelve steps has rekindled an earlier interest in Buddhism or complemented a concomitant practice of Buddhism [

56,

57,

58,

59]. The issues that these authors have faced is getting so far in their recovery, perhaps with the aid of the twelve steps, and then getting stuck, or struggling with how to integrate a practice of Buddhism and being an addict in twelve step recovery. Some feel that the twelve steps may not address deeper levels of attachment to addiction in its widest sense. Even while being appreciative of the help of the twelve step approach, some find that the language can be off-putting or applied in a dogmatic way [

60]. Some twelve step groups are experienced as having an evangelical Christian flavour, which can lead those in recovery to seek alternative forms of mutual aid [

61].

The most obvious point of connection between Buddhism and the twelve steps is meditation. Meditation is a cornerstone of Buddhist practice, and meditation, together with prayer, is included in the eleventh step [

55]. Buddhist teachings on meditation have been used to provide practical guidance for practising and elaborating the eleventh step. More generally the writers have drawn on their experience of Buddhism and being in recovery to augment the spiritual dimension of the twelve step programme.

Other areas of overlap between Buddhism and the twelve steps include having a description of suffering in life and its causes, and an ethical dimension to overcome suffering. Step one—admitting powerless over alcohol—has been linked to the first two noble truths, which are suffering and the cause of suffering, namely craving. Steps four and five, the fearless moral inventory and admitting the exact nature of one’s wrongs, can be related to

śīla or ethics, which is the first stage of the threefold way (

Dīgha Nikāya, volume ii, p. 82), as well as the third, fourth, and fifth limb of the noble eightfold path [

62].

The principal Buddhist influences have been Theravāda, especially Vipassanā, and Zen. Both tend to emphasize mindfulness and make reference to key Buddhist teachings such as the four noble truths and noble eightfold path. Therese Jacob-Stewart includes Mahāyāna elements such as the bodhisattva vow and the

bodhicitta [

63]. A bodhisattva is a being who dedicates their life to helping all other beings, thus emphasising the altruistic dimension of Buddhism. The bodhicitta can be understood as the inner aspect, experienced as the urge to help beings. According to the Mahāyāna, on becoming a bodhisattva an individual takes a vow or series of vows that supports his or her altruistic endeavours, such as vowing to master all teachings [

64]. Bill Krumbein uses koans—a problem without a logical solution—to meditate upon and use in discussion groups [

65]. This acts as another bridge between Buddhist practice in the form of silent meditation (practised alone or with others) and the twelve step format of discussing issues in groups.

While they have not sought to substantially change or replace the twelve steps, some of the authors have recognized stumbling blocks that some people in recovery may encounter when trying to follow a twelve step approach. Kevin Griffin notes that the terms God, faith, powerlessness and prayer may alienate those without a religious training or who have rejected their religious upbringing [

57]. He suggests that Buddhism may offer an alternative to the Judaeo-Christian emphasis in much of the twelve step literature. He has described how higher power can be thought of in terms of various Buddhist ideas and practices such as karma, mindfulness, love and wisdom [

66].

The last decade has seen the proliferation of a range of Buddhist or Buddhist inspired twelve step groups, especially in the United States. These groups variously emphasize meditation in general, mindfulness or Buddhism. Sometimes they are called an Eleventh Step group, focusing on practising the eleventh step with the emphasis on meditation, or a fifth precept group—the fifth precept referring to abstention from intoxicants. Some groups explicitly explore Buddhist teachings and some may be part of a local Sangha. The Buddhist Recovery Network provides information on recovery groups suitable for people interested in Buddhism. The organization lists 94 groups in the United States, five in Canada, three in the United Kingdom and Ireland, two in Australia, one in New Zealand, and two in Thailand [

67] Individuals utilizing Buddhist teachings in a twelve step program may find this combination supportive to their recovery. The twelve step approach may be helpful with its group and sponsor format and in providing a spiritual path. The Buddhist teachings may enhance the benefits of the twelve step approach, especially by developing awareness through meditation, learning nonattachment to the ego, and giving a connection to a collective spirituality [

68].

Sharon Hsu and colleagues have noted some differences between Buddhism and the twelve steps including the aetiology of addiction, views on aspects of treatment, and the extent of cure possible [

69]. The twelve steps has a disease model, whereas Buddhism emphasizes lack of awareness as the cause of addiction. In the twelve steps abstinence is required and there is a dichotomous discontinuity between substance use and sobriety. Buddhism has a more continuous model, which is compatible with harm reduction. The twelve steps suggest there is no ultimate cure from addiction, whereas Buddhism espouses complete freedom from all addiction in Enlightenment. Perhaps the latter comparison may be considered unfair, given that the twelve steps are a set of practices directed at a particular behavioural outcome, as oppose to a whole soteriological worldview, nevertheless some may find the optimistic stance of Buddhism supportive to their recovery.

6. Contemporary Approaches to Recovery

While a number of the authors above have sought a Buddhist approach to recovery based on the twelve steps, more recently some have been exploring what a Buddhist approach to recovery might look like taking the Buddha’s teachings as the starting point. Noah Levine has put together a programme based on the four noble truths and the eightfold path [

70]. He explains the first truth as addiction creates suffering, and the second as the cause of addiction is repetitive craving. The third truth states that recovery is possible and the fourth, the path to recovery, uses the eightfold path with ethics, meditation and wisdom as the means to creating sobriety. There is a strong emphasis on taking refuge in the three jewels, which Levine describes in terms of taking refuge in one’s own potential or Buddha nature, in the four truths (as Dharma), and those you meet and connect to in Refuge Recovery meetings (the Sangha). He has set up, and in his book encourages others to set up, such meetings to practise the teachings that he advocates.

Valerie Mason-John and Groves, in their Eight Step Recovery, also draw on the four noble truths and the three refuges, and stress the importance of on meditation [

27]. Their work running MBAR courses forms a foundation and there are influences from cognitive-behavioural approaches to working with addiction. Joan Duncan Oliver comments that although both this and Levine’s approach are explicitly Buddhist, the twelve steps perhaps unsurprisingly seem to hover in the background [

71]. She also questions how helpful the books will be on their own without the support of a group, a Sangha. Levine encourages setting up refuge recovery groups, and list groups in 25 locations, mostly in the United States [

72]. Mason-John has made suggestions for setting up eight step recovery groups, which appear to be beginning to form [

73].

7. Conclusions

The Buddha was aware of the problems caused by addictive behaviour, especially drinking and gambling, and gave advice to help his followers. His main focus, however, was helping people to attain enlightenment, as he had done, and which is characterised by wisdom and compassion. After his early disciples had, like the Buddha, gained enlightenment, he encouraged them to teach the Dharma out of compassion for the benefit of others (Vinaya Mahāvagga, volume i, pp. 7–20). The response of the Thamkrabok monastery in Thailand to the heroin epidemic can be seen as a continuation of this compassionate activity. Similarly in Japan, Ishin’s development of Naikan appears to have been a compassionate response to pass on what he had discovered in a form that was accessible to a wide section of society. This work has then been extended to include helping people with addiction problems.

The wisdom side of enlightenment includes a detailed understanding of the workings of the mind, as well as practices to help move towards enlightenment. Over the last twenty years, the value of elements of this for the treatment of addiction, have begun to be explored in the West. There have been two main strands to these developments. Firstly, mindfulness, which has become a popular form of treatment for a wide range of psychological disorders, has been applied with some success to addiction problems. Secondly, members of the mutual aid movement have started turning to Buddhism, especially to further the spiritual implications of their recovery as implied in for example the eleventh step. In twenty-first century countries with a strong scientific tradition and a pluralistic society, Buddhism, with its emphasis on empiricism and practical application, may be particularly attractive.

For the future, more work needs to be done to establish the efficacy of existing practices, like mindfulness, in the treatment of addictions. Explorations, which have just begun, of a fuller engagement with all aspects of Buddhism, need to continue to optimize the possible benefits for addiction recovery.