Abstract

In this article we outline a theoretical and methodological framework for spiritual identity as meaning in folk psychology. Identity is associated with psychological elements of personality that help people manage a time-bound existence. This discussion is extended on anthropological grounds, noting that spiritual goals are reinforced when they become symbolically self-important, often through religious ritual. This makes religious tradition and culture of monotheist exemplars centrally important to understanding idiosyncratic folk narratives like spiritual success.

Introduction: Spiritual Identity and Narrative

As the introduction to this special edition explains, spiritual exemplars are persons who have acted and achieved. Also as explained, their actions and achievements are motivated by powerful faith. But how are we to explain the workings of powerful faith? Here, we explore one way of explaining, namely, in terms of mature spiritual identity that becomes a core feature of the faith of spiritual exemplars and also becomes a way of connecting personality traits to goals is taken to be sacred within the exemplar’s spiritual tradition.

Spiritual identity is dependent on a narrative. The story draws upon historical truth but is never meant (or able) to provide a completely accurate, factual account of history. It does, however, provide meaning. This account of spiritual identity follows closely the model laid out by Dan McAdams, the most renowned expert on identity since Erikson. For McAdams, identity is embedded in personality and memory. But it’s more than this. Identity is the mythical story you and I create which helps explain our behaviors, experiences, and relationships. We have many versions. It can be the superficial stuff you tell strangers at a cocktail party. It can be the naked honesty of conversation with your spouse at the end of a difficult day. Whether the issue is moral identity or ethnic identity or whatever, what’s critical is the meaning we attribute to this story, what it means to the self, and how the narrative shapes our behavior into the future.

For McAdams, story specifically assigns meaning to experience [1,2]. This pushes important theoretical and methodological buttons. Stories require embodiment; organic encounters with marriage partners or morning prayers. But there is more. Stories are speech acts that creatively assemble experience into characters and plot, a process dynamically engaged with religious and cultural context.

As an example of how this happens in the lives of spiritual exemplars, consider Riza, a 46 year-old Muslim spiritual exemplar from the Van Nuys region of San Fernando Valley in Los Angeles. In one conversation, Riza reflects:

I try to be helpful to other people every day. My goal is not to live for myself but for society. I really care about spirituality, about religion. I try to achieve the best, spiritually, and I don’t care about my success in this life as much as I care about spiritual success. Because things are not in our hands, right? Things change and we shouldn’t be worried about what is not in our hands.

Riza’s spiritual identity myth is directed toward social obligation and responsibility. These are framed in transcendent terms, particularly as Riza reaches for spiritual success. It is likely that others corroborate this goal within his Turkish Muslim community. Even if the expression originates with Riza, related meaning extends well beyond his person.

Furthermore, Riza’s spiritual identity myth is based on experience, which is interpreted as religious experience. All this is consistent not only with McAdams’ model but with that of Ann Taves as well. She is a distinguished scholar of religion at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her most recent book provides an incisive review of theoretical and methodological issues in the study of religious experience [3]. It happens that religious studies, much like psychology and anthropology, is saddled with its share of internal conflict. Early in the last century a score of pioneering researchers argued that religious experience was sui generis, a categorically unique phenomenon necessitating special interpretive methods [4]. Critics mustered against this argument, contending that religious experience is inevitably bound to social influences like any other kind of narrative. Consequently, religious experience was a suitable candidate for exposition with tools of critical theory from literature and feminist studies [5]. Toward the end of the twentieth century, these camps evolved into perennialists (who believe religious experience is physically embodied) and constructivists (who believe religious experience is socially constructed through language). Although an uncomfortable truce is currently observed, the field of religious studies languishes for lack of strategies integrating the best from both worlds. The vacancy is problematic given advances in the study of experience from psychology and anthropology. A way forward might emphasize interdisciplinary approaches leveraging recent contributions from these fields [6].

Taves aims at the problem of how meaning is created from religious experience. Central to her proposal is folk psychology or the commonsense manner by which humans make meaningful associations between perceptions of the world and mental states or behavior. In folk psychological research, consideration is given to “cross-culturally stable assumptions that we use to predict, explain, or understand the everyday actions of others in terms of the mental states we presume lie behind them [7].” Riza’s story is situated within a web of social and transcendent influences. From a folk psychological standpoint, the meaning Riza assigns to spiritual success arises from organically embodied experiences fashioned by religious context and culture. Meaningfully sensitive interpretation of spiritual success is unlikely without consideration of Riza’s individual and relational perceptions of its significance. Folk psychology accounts for religious experience in spiritual identity as an everyday event involving individuals and their communities. Thinking anthropologically, goals are reinforced when they become symbolically self-important, often through religious ritual. This makes Riza’s religious tradition and culture centrally important to an understanding of matters like spiritual success.

However, there is more to spiritual identity than assigning to oneself some overall goal or personal, overarching value such as spiritual success. McAdams’ model is reminiscent of nested Russian figurines known as matryoshka dolls crafted to fit tightly inside of one another (see Figure 1). The inner (smallest) doll represents a unique cache of traits capturing our individual style of social adaptation. Traits are familiar patterns of interaction with descriptive labels such as extravert or agreeable or conscientious. The middle (medium sized) doll manifests strivings described in terms of characteristicadaptations or goals. The outside (largest) doll comprises the identity story of central interest to this chapter. Identity myth is forged on the basis of goals that become personally significant after years of trait-influenced interactions with others. For McAdams, identity cannot happen without these other facets, nor can they independently exist without eventually contributing to some kind of mythically storied self. All three levels of personality evolve in response to social and environmental pressures requiring adaptation for physical requirements (what will I eat?), recognition of potential threats (will this person hurt or take advantage of me?), psychological needs (do I have skills?), and social contributions (can I contribute to the group?). The matryoshka dolls of personality helped our distant ancestors manage these pressures unfolding in time. The resulting knowledge is hard earned, becoming applicable to future problems requiring individual and collective adaptation.

The McAdams model and matryoshka doll analogy suggests that identity myth serves, then, a meaningfully integrative function, unifying traits and goals toward a stable sense of self across variations in time, place, and role. We are able to envision ourselves in the future contingent upon successful integration of episodes and experiences from the past. To the extent we integrate episodes and experiences into the self, we are able to maintain a consistent identity. This unfolds over years, not months. It begins in adolescence with the debut of abstract self-reflection. Unlike grade-school children, adolescents are able to connect real world behavior with trait abstractions (I feel good about volunteering because I’m a caring person) [8]. But time spent with high school youth quickly reveals that identity is not yet integrated. Youth are famous for chameleon-like identity shifts based on changing temporal or social contingencies. They may present as startlingly different people with peers relative to parents, often using different vocal intonations, words, and grammar in response to social expectations.

Figure 1.

Russian matryoshka dolls. Photo by Heather Connolly.

Traits

Personality traits are ubiquitous in popular culture; a familiar topic on television talk shows, around office water coolers, and with college students taking online surveys in late night dorm sessions. Traits are internal dispositions characterizing responses to a given situation. Traits are stable to the extent that we might experience the same response across a variety of situations. For example, a highly introverted person may respond with anxiety when confronted by large groups with noisy people. Football games, large parties, and even religious services might elicit the same response despite the fact that each of these situations place different requirements upon the individual. Expectations for socializing at a football game are markedly different than a party, which differs again from religious services. The psychological research literature indicates that while traits modestly predict what an individual will do in a situation, they are robust predictors of vocational success [9]. Traits have a tendency to be passed along from generation to generation. Studies of global twins suggest that at least half of personality traits are replicated between parents, children, and siblings. Traits are a personalized signature of social interaction anticipating the formation of spiritual identity myth [10]. In the following account of Edward, a spiritual exemplar, we see how a trait (being gregarious) can become integrated into a personal narrative that establishes a spiritual identity:

Sawtelle is just west of Interstate 405 in Los Angeles. Predominantly residential, the flat topography is dominated by the Wilshire Federal Building, a steel and concrete monstrosity beloved by anti-government protesters looking for scapegoats. The Sawtelle neighborhood is bordered by Santa Monica to the west, Brentwood to the north, and Westwood directly east. Colorfully multiethnic, Sawtelle is home to a closely-knit Japanese community. Local nurseries showcase this influence. Manicured conifers and shrubs await transplantation into backyard kaiyu-shiki or miniature walking gardens. The sushi bars of Sawtelle are a lunchtime favorite for west LA businesspeople who pack establishments with frenetic smiles and buzzing iPhones. Mealtime conversations swing in bipolar cadence between physical surroundings and the sirens of cyberspace.The exemplar is short with thick fingers and finely textured brown hair. Edward is 49 years old. Quick to laugh and poke fun, he archly claims his mother thought he should become a longshoreman! Seated in his law office, we are a world away from the docks at San Pedro. Edward speaks quickly and with a slight lisp. His eyes are squinted in mischievous deliberation, pulling the corners of his mouth upward. On the wall behind Edward’s head is a Celtic cross [⌖], artifact from a recent pilgrimage to explore his Presbyterian heritage in the Scottish Highlands.“I’ve been told that I’m highly gregarious. I’m not sure what that means for me, but I know what it means for other people. The hard part is figuring out what these things mean personally. [ruminative, scratching chin] Maybe the best way to know is through relationships. My spouse is very intuitive, very introverted. We are absolute opposites. We complement each other well and people have lovingly said that we fit together. I think other people get that pastoral side from me, although she has just as many feelings as I do, not to mention intellect and training. But she doesn’t show these things very easily, when they come naturally for me. So being gregarious probably means feeling and caring and warmth. People get these things from me.”

While traits describe individual differences, they are revealed through social interactions. Edward uses the trait label gregarious. His initial struggle to describe gregariousness is amended with insight that partnered relationships offer a kind of mirror for personality traits. Perhaps even more than his spouse, it is the comments made by others describing their partnered compatibility that informs Edward’s reflection. Gregariousness is not spiritual identity. But the relevance of the trait to identity story is evident through the patterned experience of social interaction Edward hears from others who reflect back on his interpersonal style. In this instance, Edward uses trait knowledge to help align interior world with external behaviors. Gregariousness helps integrate Edward’s personal goals with actions. The trait confers a high value on relationship with others including the divine. Operating within conscious awareness of his own affability, Edward’s goals to stay connected and affirm others are made consistent with actions, creating a mutually reinforcing circuit. Moments where caring and warmth positively influence others become recorded in Edward’s memory as precursor to purpose. Over time, this knowledge becomes germane to identity [11].

Characteristic Adaptations and Goals

Of course, gregariousness and traits are not all there are to Edward’s spiritual identity. There are characteristic adaptations and goals as well. Characteristic adaptations are “characteristic” because they represent the enduring psychological core of the individual. They are “adaptations” because they respond to a changing environment. The importance of characteristic adaptations or goals to spiritual identity is considerable, yet these are somewhat less transparent than traits. We do not encounter self-help books with characteristic adaptations in the title, even though many such books are about goal-oriented processes (improve your marriage, become a successful leader, manage anxiety). Reaching for Oprah transparency, one researcher observed that traits pertain to the “having” side of personality whereas characteristic adaptations (goals) are related to the “doing” side [12]. The goals we construct are influenced by trait knowledge. Goals extend such knowledge into practice. They contain effects of traits, informing value judgments on moral or religious importance.

Recognizing that gregariousness is linked with traits like “caring” and “warmth,” Edward might construct a characteristic adaptation (goal) of visiting the sick in hospital, working closely with clergy. There is nothing explicitly linking trait gregariousness with compassionate care for the sick. Yet there can be little doubt that Edward’s interest in this kind of service is informed by years of accrued knowledge on mirrored elements of gregariousness—the kind of experience others identify as “caring” or “warm.” Edward offers folksy detail:

“I’m in this job because I love using my gifts to help others. It doesn’t matter whether I’m working as a lawyer or in the church; I’ve done ministry all my life. I can’t think of anything else that matters as much as serving others. I should also say that I get a lot of passion, exuding and infusing, from music. It carries over into all of my goals for service—how I speak, how I play. I experience a lot of good moods, a lot of happiness, a lot of harmony. I love to bring good stuff and good things to people, even if it’s something as simple as encouragement. It’s my goal to encourage others. I like to make people happy. My emotions are sometimes from A to Z. I have my human, “at home emotions” as well and the introvert takes over, very pensive, or even moody—I can be withdrawn. I need to have that alone time in order to be that gregarious person. When I’m alone I listen to country western music, I listen to great classics—the pianists. I can become spiritually swept away by fiddle, banjo stuff. And there’s salsa, one of my favorites.”

Edward’s goals are directed toward service. Gregariousness is loosely associated with his reflections. Trait knowledge is qualified by the accumulation of experiences that validate the importance of service across a range of situations and relationships. These culminate in a specific goal—to serve others. Interestingly, Edward links his reflections on service with emotions quickened by music. McAdams’ scheme accounts for a motivational component to characteristic adaptations that are emotional in nature. We might infer from Edward’s narrative that emotions which sustain his passion to help others are similar to those elicited through musical experience. These underlying emotions (both positive and negative) are probably of a kind associated with transcendent experience. His use of the word “ministry” to qualify service certainly signifies a vertical referent. His use of the word “spiritual” in association with fiddling and banjo music rounds out the transcendent flavor of the account. We expect that goals and valuations connected with spiritual identity myth are emotionally cued, a critical component in understanding where identity story comes from and what makes it significant to behavior associated with transcendent experience.

The integrative premise of identity story carries over into other aspects of interpersonal functioning. This is visible in Edward’s stable responses to questions of time and role:

“What will you be like in 10 years?”“Hopefully a better, stronger, wiser mentor to others. I’ll be the same person, just more so. I hope to be even better at putting myself in situations which play to my strengths. I want to be thinking about the end of my life, not in the doomsday sense, but straining to be deliberate in a mentor capacity, striving for being an excellent leader. A humble, excellent leader. These are my goals now in the short term, but they also go into the long term. I’m content with myself right now. I love it here, that’s fine, but a time will come for the next adventure and where I can best serve. I’m going to be there, ready for adventure—looking for the really cool things that will happen, and with God doing it all.”“What kind of person does your mother or father expect you to be?”“Well, that’d be my mother. I think given the complications of how I came into this world, my perception was that she always wanted me to turn out right. She brought me up in the church; she wanted me to turn out right and not make the mistakes that she made or be one of those kids in church that throws God away and goes to the other end of things. She always expected me, didn’t voice it, but really wanted me to come out right. I think it was just as simple as that. I think a part of that is still there.”“What kind of person does your best friend expect you to be?”“Much the same. I think to be real, to be my very best. All of the descriptions that I gave earlier. We talk about anything and everyone and we want to make the world a happy place! I remember I spent one Fourth of July with him and we sort of came to this conclusion, wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could get all of our friends together into one happy family. Help each other become the very best. His reply was, ‘well maybe that’s what heaven will be like.’”

Edward’s narrative doesn’t change much with regard to circumstances. This is mature identity myth, a composite of episodes and experiences referencing self. Trait knowledge and goals are woven into future-oriented projections of self, engaging relationships marked by different responsibilities.

Developmental research indicates maturation occurs where individuals move from a self of concrete action to a self of agency or conscious intention. The transition is typical of adolescence, with ongoing reformulations across the life span. Our younger selves were focused on concrete actions (I am good at helping mom) which later yield to more abstractly sophisticated accounts (I’m a good leader because I’m an outgoing and sensitive person). The crux of the transition is found with recognition that self is capable of influencing and controlling external events. Adolescence inaugurates a process whereby abstract experiences of self are catalogued in memory [13]. The mature result is found in Edward’s identity myth. He is compelled to become a better mentor, to turn out “right” in the perception of his mother. New episodes and experiences support the notion that gregariousness and service goals are capable of exerting a lasting, positive impact on others. This becomes stronger with time, expediting a more nuanced folk psychological understanding of personal values and goals that reference divinity.

To further illustrate the nature of mature spiritual identity as a partial explanation of how spiritual exemplars and their faith function in everyday life, consider the following exemplar, Patricia, who lives within yet another faith tradition but who illustrates common features of powerful faith and spiritual identity.

We are in Mar Vista, directly south of Sawtelle in Los Angeles. The swagger of Venice Beach is nearby to the west, with Culver City and Interstate 405 to the east. Hilly reaches of Mar Vista (Spanish for ocean view) serve up panoramic scenery and ridiculous property values. The neighborhood is famous for its collection of Gregory Ain homes. A decorated architect who specialized in affordable modernism, Ain is a postwar staple in LA. The local farmer’s market takes place weekly on the corner of Venice and Grand View. Ubiquitous throughout Southern California, farmer’s markets deliver community identity and antioxidant produce against the entropy of life spent behind carcinogenic tractor-trailers hurtling down the interstate.The spiritual exemplar is named Patricia. She is of average height with closely cropped grey hair and dark complexion. A youngish 62, she is an amateur linguist—able to easily switch between English, Yiddish, Spanish, and German. Educated in Tennessee, Patricia spent much of her working life in Central America, using her microbiology background to help indigenous peoples secure reliably clean drinking water. Her Jewish roots are Polish, Lithuanian, and Hungarian. Like Riza and Edward, she is committed to service. Earlier in the interview Patricia states her life story revolves around the word compassion. She pauses and reflects before offering a soliloquy on what this means to her identity.“I think we are moving to a place where structure is important and the mitzvah [viz., commandment, referring to 613 divine commandments given in Torah] is important and the spiritual discipline that Judaism offers is incredibly valuable. I impose these restrictions on myself because I believe that they will better my life and bring more holiness and more blessing and more peace and more harmony and more compassion to others. I’m an everyday follower. I’m a thinking person and I’m an evolving person and religion should shape us to be the very best, the most compassionate we can be at our moment in history. [waving hands] Judaism kind of got stuck in seventeenth, eighteenth centuries where things just froze out of fear, reaction to the Enlightenment and everything else changing. That’s when orthodoxy grabbed hold. But Judaism used to be a much more fluid tradition and was very open to change and very open to radical ideas and very involved in the world. I’m trying to get back to that and to think about it—theology that helps people—with compassion. I think about a different approach, we have to make our commitments with religion that has not become like everything else. You can choose to diet, you can choose to exercise, etcetera. My practices have spiritual consequences. That’s what I’m thinking about right now, spiritual consequences.I approach my life in a spiritual sense. I pray three times a day and believe that I’m not necessarily in control of everything. I partner with God—I’m a follower of Abraham Joshua Heschel, a theologian and philosopher who talked a lot about being partners with God. So I wake up every morning and thank God, I pray and take time out of the day, three times a day to stop and pray before I eat, after I eat. It’s an important daily ritual. In a religious context, I try to see the world through the lens of the divine. Everything has the potential to be part of God’s will, whether I’m at a baseball game or observing Yom Kippur, I try and operate with the fact that the spiritual is always happening, it’s not compartmentalized and that’s a message I try to give to people. You don’t wait for the big moment, you don’t need to come to synagogue; it can be anytime, the moment you open your eyes and in fact, discover you’re breathing. [chuckling] I meditate on that regularly, every breath is a miracle and I try to keep a childlike amazement and wonder about the world. We tend to become jaded as we get older. My grandkids are just in awe at a shoestring! [laughs] Part of it is the newness of discovery and part of it is the ability to still be awed and see that everyday the amazing becomes possible. We pray in our liturgy, we should pay attention to the daily miracles and I think too many people fail or refuse or are afraid to do that or just don’t understand what it means.I believe that God is an ever-present force, power, being in the world. I don’t think God directs the world with a hand, but I think that God is part of everything. I believe God gave us a lot of power, I think God had to look past a lot of God’s self to do this, but I definitely feel that the world is not totally random and there’s an operating force in nature. I’m not sure I believe in fate or destiny, or ‘God made that happen;’ that’s where Jews and Christians are a little different—I’m not completely sure about the Muslims—but you’re not going to hear Jews very often say, ‘God called me to go take that job.’ I’ve never heard God tell me to do something, but I feel that some conversations are a revelation from God. That God opened my eyes and said, ‘Here I am, now pay attention, be aware.’ I think moments like that can happen, that wake people up to a kind of potential and I believe that we have the power to make dreams into a reality. But I also think we’re in a hard place in the world, it’s a difficult time and we feel like we don’t have much power, things are so vague and out of our hands in the human realm, let alone the divine realm. I feel that a lot. I can’t make a difference, I’m just a little regular person, because there are more important people that can make a bigger difference, you know. I think this is an ever-present challenge, the tower of Babel—that’s what the story is about in Genesis, people were trying to be God and I think we let that happen. I believe that we all have the power to make change in our lives, in our world, that nothing is forever destined to be one way.”

Patricia responds to human needs and conflicts much like Riza and Edward—with compassion. Her myth is filled with commentary regarding how compassion changes life for the better. Not surprisingly, her life revolves around the selves of others, with rhetorical flourishes demonstrating a mature theory of mind. This perspective-taking ability includes the divine. Compassionate behaviors disclose the Jewish God through a fluid, evolving tradition. Yet despite this flexibility, Patricia draws a line in the sand. She makes a distinction between theory of divine mind—appropriating the world through the lens of God—and the Babel quest to usurp divine prerogatives as self-appointed human divinities.

Putting herself in God’s shoes does not make Patricia a god. Instead, Patricia lives through partnership with God, a richly symbolic description. She borrows the concept from Heschel as a way of understanding how God’s compassionate goals become her own goals. She sustains this difference through observance of the commandments, meditative breathing, and ritual prayer with meals as anchor. Emotional memory may explain the biological reinforcement of empathy and moral emotions that make compassion Patricia’s signature objective. But this does not account for the self-importance of compassion in her spiritual identity narrative. The symbolic meaning of Patricia’s divine partnership happens through processes that differ from Russian dolls. The next section borrows content from anthropology to deal with meaning and its emergence through religious observance, ritual, and culture.

Spiritual as Folk: Anthropology

Spiritual identity is story that joins self with divine and interpersonal goals to emphasize purpose, generativity, and social responsibility. In Patricia’s folk psychology, compassion is made meaningful through partnership with God. More than trait knowledge, her spiritual identity myth underlines the self-importance of compassion through symbol. Partnership with God begins with observance, mediation, and ritual prayer. These mature into a sense that God is compassionately engaged, and spiritual events are always happening. A collage of fairly mundane activities is ritualized through tradition and community, supporting folk psychological understanding that makes compassion paramount.

By considering divine goals through an extended theory of mind, exemplars construct meaning not just through spiritually successful or compassionate interactions with others but also through practices associated with religious tradition. This makes Patricia’s social context, specifically her Jewish heritage, essential toward an understanding of why compassion matters to spiritual identity narrative. While Rabbi Heschel may have coined the term, divine partnership acquires its compassionate meaning through observance and ritual of the Jewish faith.

But how exactly does Patricia create self-important meaning? To this point we have considered psychological concerns in identity story. While helpful, this brushes past a simple fact with consequences for spiritual identity. Spiritual exemplar narratives are composed of language. This is an acknowledged breakthrough in evolution for a range of species. Linguistic exchanges among dolphins or higher apes might communicate threats or territorial boundaries associated with mate selection. Farther down the taxonomic line, proto-linguistic communication captures the well-known ability of honeybees to “dance” in a manner conveying valuable information regarding the proximity of food. An evolutionary anthropologist at the University of California, Berkeley, Terrence Deacon notes that while many species evidence linguistic communication, only humans have developed language describing symbolic thinking or representation (literally, “re-presentation” of an external object or concept in memory) [14]. As with dolphins and honeybees, our language contains descriptions of the environment, objects, or conditions. However, we additionally use language to communicate abstract concepts and ideas. Patricia’s use of partnership to describe her transcendent experience is abstract and symbolic. Invoking the concept of collaborating people, she raises the level of abstraction by involving the divine. This symbolic innovation communicates something of great personal and spiritual significance.

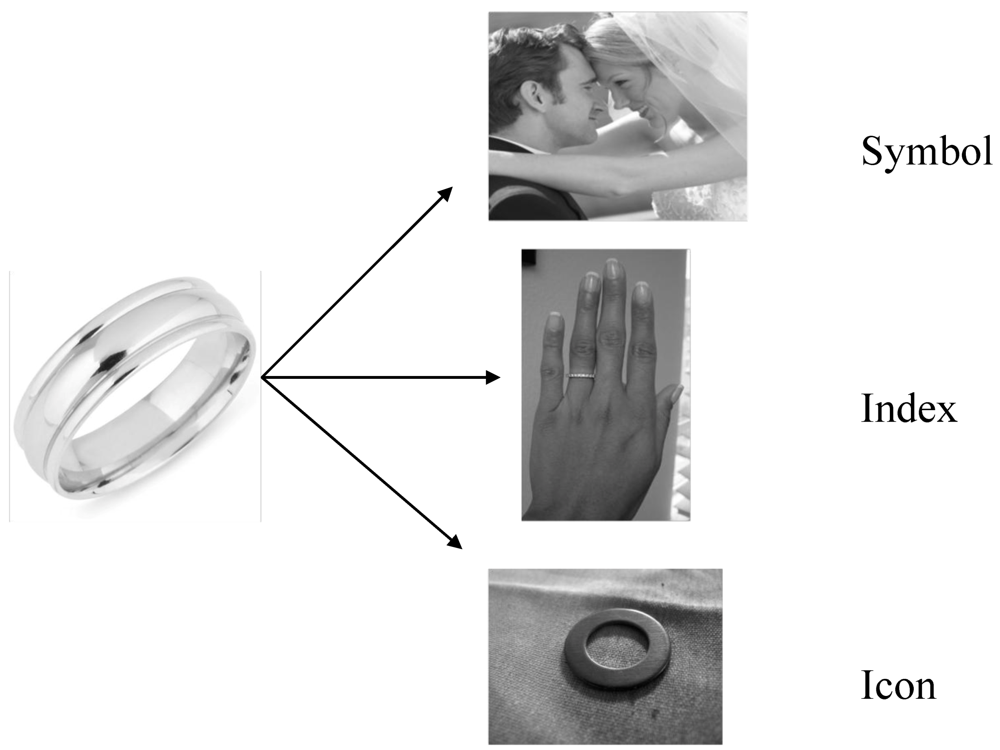

To fully appreciate Patricia’s spiritual identity narrative, we need to know how humans use language to express symbolic meaning in ways that are self-important. Symbol is a major concern for Deacon, who theorizes about the manner by which language co-evolved with the human brain. He rehabilitates the work of a gifted American philosopher named Charles Sanders Peirce from more than a century ago. For Peirce, language is affiliated with levels of mental interpretation that scaffold symbolic meaning. The first level (icon) constitutes basic interpretation whereby signs are recognized through comparison with other items in the world. Iconic comparisons determine physical similarity and likeness. Consider a gold wedding ring [15]. From an iconic standpoint, the ring resembles things like washers, doughnuts, and hula-hoops. In addition to shape, the ring provides other visual cues including color (gold) and luster (metallic). These are similar to golden metallic objects we might regularly encounter such as picture frames, necklaces, and fillings in our teeth. Iconic similarity provides orientation in the process of understanding the wedding ring. Yet this is only an initial step. None of the words used to describe these iconic resemblances (washer, doughnut, hula-hoop, picture frame, necklace, filling) manage to capture the meaning of the ring, or its self-importance for those who are married. They are descriptors of physical analogues found in the environment.

The second level (index) of interpretation builds upon the first. Pulling together various bits of iconic information, we are able to make physical and temporal connections between signs. Indexical meaning is constructed from factual correlations or associations known from experience. From past encounters with other people, we know that rings are correlated with human anatomy. They are pieces of jewelry to be worn or displayed. Our knowledge of bodies designates the wedding ring for use on a hand rather than foot or nose. It is the right size for a finger rather than a wrist. To reach this conclusion, we quickly compile several iconic comparisons of physical likeness to locate the right association. Even children with relatively little jewelry experience are able to successfully link the gold wedding ring to a particular finger, typically the third digit from the thumb in Western cultures. Relative to iconic comparisons, indexical association requires added memory. Instead of making one-to-one comparisons, we must consider several possible associations within a category of signs—in this case, bodily appendages. While this suggests a nuanced and sophisticated level of interpretation, words indexically associated with the ring (jewelry, hand, foot, nose, wrist) again fall short of providing a richly symbolic account of its significance.

The third level (symbol) of interpretation resolves the self-important meaning of the ring (See Figure 2). Synthesizing iconic and indexical levels of meaning into a higher-order abstraction, symbol is understood on the basis of law, causality, or convention. Variations might exist with regard to cultural norms dictating which hand displays the ring (right hand in many European nations, left hand in North America), but the symbolic importance of the ring is much the same, characterizing a legal contract between two individuals often causally associated with offspring. Certain taboos indicate behavioral conventions associated with the ring, such as exclusivity through monogamy. A number of indexical correlations are necessary to construct such an interpretation. These might involve memories of wedding rings worn by parents or friends, and religious teachings on marriage. Symbolic understanding is unavoidably social as laws and conventions are established within particular religious and cultural contexts. Granted, the symbolic meaning of the wedding ring in this example is explicitly Western. Many variations in law, causality, and convention exist between cultures, not to mention religious traditions. But the underlying scaffold of meaning is the same across people groups. In our example, the ring is symbolically understood with language that is reflective of law (contract), causality (offspring), or convention (monogamy).

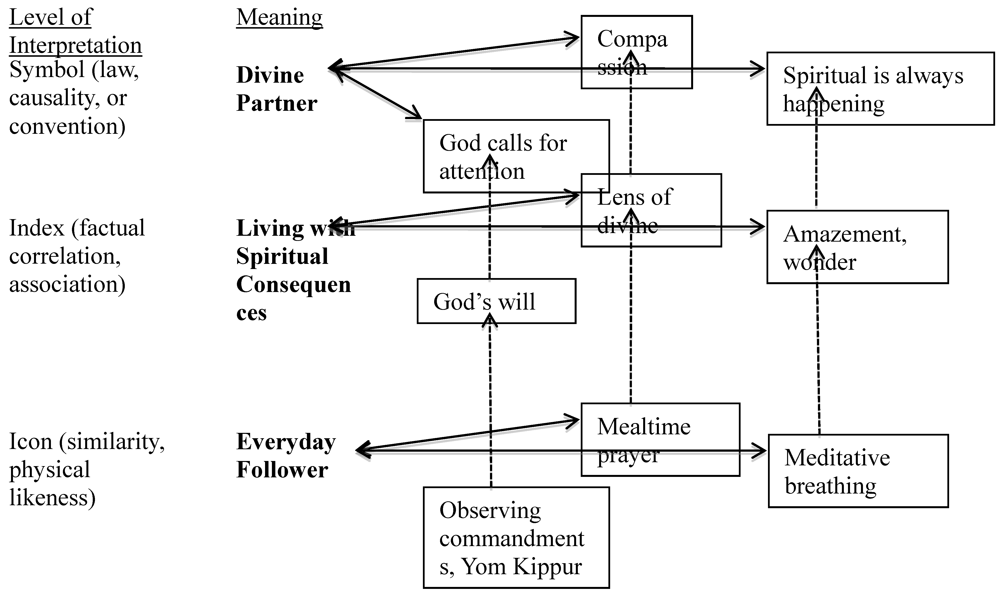

Peirce’s scheme offers a template for Patricia’s folk notion of divine partnership. While self is somewhat more abstract than a gold wedding ring, it is no less comparable to external signs corroborating iconic meaning with the divine. The foundations of partnership are indicated through iconic likenesses through Jewish observance and ritual. Patricia makes a concrete reference to self as an everyday follower. Meaning is established through observance of the divine commandments, and by extension, holidays such as Yom Kippur. Being an everyday follower has physical analogues in actions like meditative breathing and ritual prayer before eating. Patricia’s observance and ritual behavior confers more than just comfort. It helps generate a catalogue of iconic comparisons between self (everyday follower) and divine (understood through concrete observances and rituals structured by religious tradition). The self-important meaning of divine partnership is established through the routine of observance and ritual, grounding intangibles such as self and divine in the physical world. To be sure, her account does not mean that spirituality must always be manifested in objects or actions in order to be meaningfully self-important. But it does suggest that a symbolic metaphor (divine partnership) can be reinforced in self-important ways through iconic comparisons involving observance and ritual. Iconic similarities between self and transcendent experience make it easier to construct divine theory of mind, and subsequently, Patricia’s compassionate goal mirroring divine prerogatives.

Figure 2.

Symbolic representation. Adapted from Deacon (1997).

Iconic meaning in observance and ritual can be extended through indexical correlation with physical and temporal events. Patricia makes these connections with a self-important observation that my practices have spiritual consequences. Iconic comparisons between self (everyday follower) and divine through observance or ritual anticipate factual associations. These support a more sophisticated understanding of self (living with spiritual consequences). As Patricia is unconcerned with presenting an example of Peirce’s scheme through her story, some latitude is required to connect the dots between iconic comparisons (observing commandments, meditative breathing, mealtime prayer) and indexical meaning. Her narrative offers interesting possibilities. By her own account, observance is factually associated with knowledge of God’s will. Meditative breathing is associated with amazement, a childlike sense of wonder about things like shoestrings. Mealtime prayers are linked with theory of mind through reference to the lens of the divine. These are physical (emotional) and temporal (knowledge, perspective) implications of observance and ritual. In Patricia’s vernacular, identity as an everyday follower is elevated to self living with spiritual consequences—facts collated from touchstones of Jewish tradition and religious practice. Indexical association provides a cache of knowledge linking self with the divine.

But this level of interpretation is not necessarily symbolic. Divine partnership indicates some kind of collaboration characterized by law, causality, and convention (See Figure 3). Factual indexing of observance into knowledge of God’s will is relevant to a partnership that acknowledges human smallness, inadequacy, and frailty. For Patricia, God calls for attention. This does not squash human initiative but rather qualifies it—a law constructed where people are partners with God. Indexing of meditative breathing into amazement and wonder supports an alliance between self and divinity. This is sufficiently meaningful that randomness no longer provides adequate metaphysical explanations. For Patricia, the spiritual is always happening, a statement that divine transcendence inhabits everything with intentions that are revelatory rather than directive or fateful. Factual indexing of ritual mealtime prayer into divine theory of mind becomes a basis for shared goals which spotlight compassion. Patricia believes religion should shape us to be the very best, the most compassionate we can be at our moment in history. In a surprising turn, she makes religious tradition central to the establishment of behavioral conventions through holiness, blessing, peace, harmony, and compassion to others. These aspects provide richly symbolic understanding of divine partnership. The roots of self-important meaning are deeply intertwined with religious tradition and community such that her spiritual identity myth flows from a quiet sense of inevitability—Patricia shares God’s goals not from obligation but toward a vividly symbolic understanding of what it means to be human.

Figure 3.

Symbolic representation attributed to Patricia’s use of partnership as self-important transcendent meaning.

Divine partnership is the self-important basis for compassion in Patricia’s folk psychology. She is compassionate because she is bound to charitable goals of divinity through observance and ritual tradition of Judaism. Symbolic meaning associated with partnership is sufficiently detailed, rich, and pervasive that it occupies a portion of her identity narrative. Patricia can’t tell us what is meant by partnership in just a few words. Instead, she provides us with the context of its origins. Partnership invokes Jewish law through observance of mitzvah. Partnership reflects the implication of divinity working through physical surroundings. Partnership ratifies convention that religion is not exclusive, but obliged to create a better world. Patricia’s spiritual identity account challenges polarized conceptions of transcendence as divisive or individualized. Her story is written at a strange intersection of tolerance and tradition, without self-important arrogance. Religion serves an important scaffold in her spiritual identity narrative, providing a collective opportunity to participate in transcendent experience through concrete observance and ritual. Although we did not ask her the question, we seriously doubt her understanding of divine partnership could have become as compassionately meaningful without ritually iconic and factually indexical references that make transcendent symbol real. Patricia’s spiritual identity narrative is constructed through knowledge of traits and goals in relationships. It is self-importantly meaningful because of symbolic associations rooted in social interactions involving observance, ritual, and culturally interpretive systems.

Concluding Remarks: Listening to the Stories

Here we have considered theoretical contributions from psychology and anthropology in framing spiritual identity through understanding spiritual exemplars. The narratives of Riza, Edward, and Patricia provide useful illustrations of spiritual identity related to psychological and anthropological dimensions of meaning. Goals of compassion, service, and spiritual success come alive through unique experiences and associations recounted through their myths.

If, then, spiritual identity is storied, it seems imperative we should listen carefully to people regarding the stories they tell of their experiences—and with particular attention to the spiritual meaning found in the stories themselves. And if the spiritual identity stories have evolved within particular cultural and faith traditions, then we need to be aware of how the language of those stories contains symbols with meanings derived from those traditions.

References

- D.P. McAdams. The Stories We Live By. New York, NY, USA: Guilford, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- D.P. McAdams. The Redemptive Self: Stories Americans Live By. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- A. Taves. Religious Experience Reconsidered: A Building Block Approach to the Study of Religion and Other Special Things. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- R. Otto. The Idea of the Holy. London, UK: Oxford University Press, 1923/1958. [Google Scholar]

- W. Proudfoot. Religious Experience. Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- R.A. Emmons, and R.F. Paloutzian. “The Psychology of Religion.” Annu. Rev. Psychol. 54 (2003): 377–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Taves. Religious Experience Reconsidered: A Building Block Approach to the Study of Religion and Other Special Things. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press, 2007, p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- D. Hart, and M.P. Katmel. “Self-Awareness and Self-Knowledge in Humans, Apes, and Monkeys.” In Reaching into Thought: The Minds of Great Apes. Edited by A. Russon and K. Bard. New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp. 325–347. [Google Scholar]

- D. Hart, and M.K. Matsuba. “Pride and the Moral Life.” In The Self-Conscious Emotions: Theory and Research. Edited by J. Tracy, R. Robins and J. Tangeny. New York, NY, USA: Guilford, 2007, pp. 114–133. [Google Scholar]

- W. Mischel, and P. Peake. “Beyond Déjà vu in the Search for Cross-Situational Consistency.” Psychol. Rev. 89 (1982): 730–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Bouchard, D. Lykken, M. McGue, N. Segal, and A. Tellengen. “Sources of Human Psychological Differences: The Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart.” Science 250 (1990): 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- K.S. Reimer, B.D. Goudelock, and L.J. Walker. “Developing Conceptions of Moral Maturity: Traits and Identity in Adolescent Personality.” J. Posit. Psychol. 4 (2009): 3725–3788. [Google Scholar]

- N. Cantor. “From Thought to Behavior: ‘Having’ and ‘Doing’ in the Study of Personality and Cognition.” Am. Psychol. 45 (1990): 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T.W. Deacon. The Symbolic Species: The Co-Evolution of Language and the Brain. New York, NY, USA: Norton, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- K.S. Reimer. “Natural Character: Psychological Realism for the Downwardly Mobile.” Theol. Sci. 4 (2004): 35–54. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).