Mosques as American Institutions: Mosque Attendance, Religiosity and Integration into the Political System among American Muslims

Abstract

: Religious institutions and places of worship have played a pivotal role in American Politics. What about the role of the mosque? Does the mosque, as an institution, in any sense play a different role than that of churches or synagogues in political participation? Some scholars have argued that Islam as a religion and a culture is incompatible with liberal, democratic American values; not only is Islam inconsistent with the West, but it poses a direct conflict. This viewpoint has likewise been popularized in American and European media and by some government officials who have labeled Muslims as enemies of freedom and democracy. Through the examination of the Muslim American Public Opinion Survey (MAPOS), which has a large sample size of American Muslim respondents (N = 1410), we argue that the mosque emerges as an important indicator for Muslim social and political integration into American society. We demonstrate that not only are those Muslims who attend the mosque regularly more likely to identify as American Muslims rather than by national origin, they are also more likely to believe mosques encourage Muslims to integrate into U.S. society. Our analysis further exemplifies that mosque attendance and involvement, beyond creating a common identity among American Muslims, leads to more political participation in the U.S. In contrast to prevailing wisdom, we also find that more religiously devout Muslims are significantly more likely to support political participation. Based on our findings, we conclude that there is nothing inconsistent with the mosque and American democracy, and in fact, religiosity fosters support for American democratic values.1. Introduction

In 2004, Representative Peter King (R-NY) casted suspicion upon the Muslim American community by claiming that the vast majority of American Muslim leaders are “an enemy living amongst us” and that “mosques in this country are controlled by Islamic fundamentalists [1].” Three years after his initial remarks, Representative King continued to target Islam by calling for surveillance and infiltration of mosques because that is “where terrorists are being homegrown [2].” In order to expose Islam's “dangerous” elements in a grandeur fashion, early in 2011, Representative King held a congressional hearing in which he continued his anti-Islam rhetoric, this time claiming that “80 percent of mosques in this country are controlled by radical Imams [3].”

In direct contrast to Representative King's assertions, we demonstrate that, among Muslim Americans, mosques and religiosity are actually associated with high levels of civic engagement and support for the American political system. Unlike King, our assessment is grounded in a nationally representative survey—the Muslim American Public Opinion Survey (MAPOS)—of 1,410 Muslims in the United States, in which participants responded to questions about the importance of religion, civic and political engagement in the United States. Based on our in-depth analysis of the data, we have found that mosque attendance and religiosity are not associated with anti-American attitudes. Rather, mosques are catalysts to social, civic, and political integration, providing a place of shared commonality, identity, and culture that allow Muslims to continue to practice their religion and live their everyday lives as Americans.

In addition to evaluating King's remarks, we also address the general debate of the “Americanness” of mosques. Despite a commitment of religious freedom in the United States, some Americans have vigorously protested against new mosques in their communities. To anti-mosque advocates, and the median voter, mosques are unknown, mysterious, and even untrustworthy establishments [4]. Not surprisingly, the great majority of the anti-mosque rhetoric has centered on mosques as dangerous and un-American establishments. The implicit assumption in such assertions is that mosques are unlike other religious institutions. The important question for social scientists, then, is whether these anti-mosque enthusiasts are correct. Various religions, though receiving no governmental sponsorship, have historically played an important role in the social and political integration of various ethnic groups in the United States. As different ethnic groups have come to America, churches and synagogues have often served as a source of community and conduits of political information and participation [5,6]. Can mosques play the same role churches and synagogues have played for decades in this country? Are American mosques really any different than other religious institutions?

2. The Rise of Anti-mosque Sentiment in the U.S.

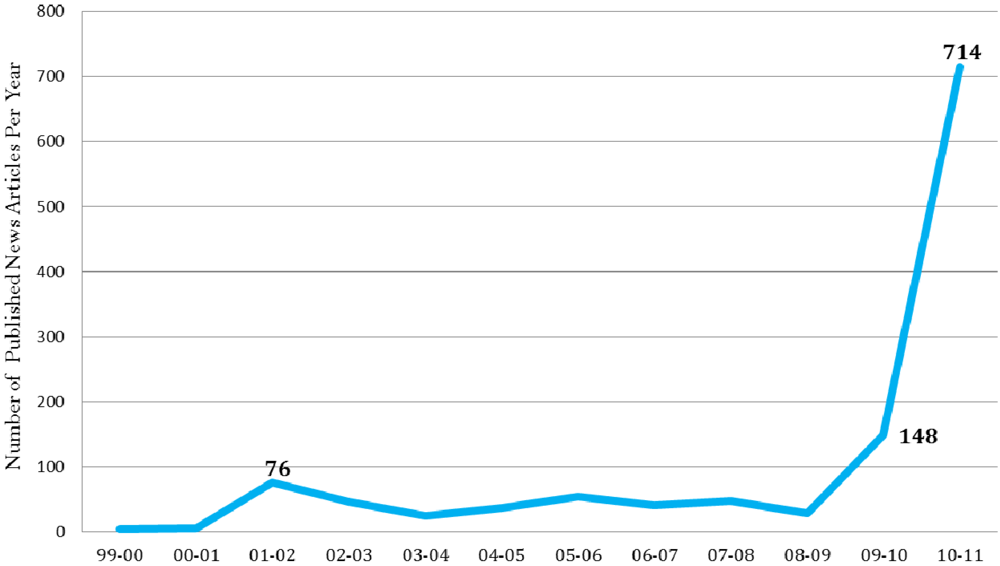

As Muslims face myriad challenges in the U.S., mosques as places of worship and socialization, have come under significant social pressure and scrutiny. The question of whether mosques and Islamic community centers represent breeding grounds for “homegrown terrorism” is increasingly becoming relevant to policymakers, scholars, and the public at large. This fact is best demonstrated through the recent growth in newspaper stories written about American Muslims and terrorism or extremism. While the public has long held anti-Muslim prejudice and stereotypes, the media is now also tapping into these same sentiments through anti-Muslim American rhetoric. Using Lexis-Nexis, we tracked the number of news articles identifying Muslims in the U.S. as associated with terrorism or Islamic extremism1, from 1999–2011, and discovered a significant spike in articles written from 2009 to 2011 (see Figure 1).

While the first spike occurs following 9/11 (total of 76 articles), coverage of American Muslims and their association to extremism leveled off in the next eight years following 9/11 to an average of 40 articles per year from 2002–2009. From April 2009–April 2010, the number of stories doubled when compared to year 2001 (from 76 to 148), and in the 12 months from April 2010 to April 2011 there were 714 news stories associating Muslim Americans with either terrorism or extremism. This recent spike parallels the growing anti-mosque movement starting with the Park51 controversy, as well as the Peter King “radical” Islam hearings, both of which put the issue of Muslim American religiosity and integration on the national agenda. It is very important to note that this is not to say the media is causing a growth in anti-Muslim attitudes through its reporting, but rather that the media is picking up on—and now more likely to report in news stories—this anti-Muslim sentiment in America today.

The proposed construction of an Islamic community center at Park51 in lower Manhattan faced mass opposition, even though this cultural center was proposed to serve as a catalyst for interfaith understanding. The opposition movement revealed a division in American society concerning whether American Muslims have rights equal to other religious and minority groups. Just as the front-page debates over the Park51 mosque had receded, Congressman Peter King, the Chairman of House Homeland Security Committee, convened hearings on the so-called “radicalization” of mosques and American Muslims.2 These hearings and opinion polls during the month of March made clear that many Americans—members of Congress included—hold strong and negative opinions towards Muslims, and are suspicious of their Islamic faith. For instance, a Gallup poll in March 2011 found that the majority of Americans felt the King hearings were appropriate, while a CNN poll demonstrated that 40% of Americans have an unfavorable impression of Islam. In the same poll, 28% of Americans agreed with the notion that Muslims living in the U.S. are sympathetic to al-Qaeda.

In this paper, we use the Park51 Islamic community center controversy as a springboard into a larger debate on the social and political integrating effects of mosques in America. As with any controversy, movement was generated in favor and against the center; issues of tolerance and religious freedom alongside commentaries of hatred and misinformation were raised during a contentious midterm congressional election.

3. Park51: The Initiation of the Present Anti-Mosque Movement

The Park51 Islamic community center, formerly known as the Cordoba House Project, was proposed by the founder of Cordoba initiative, Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf, at the New York Community Board One on March 5, 2010.3 According to Imam Feisel Abdul Rauf and his wife, who is the executive director of the American Society for Muslim Advancement, Daisy Khan, the project is intended to foster better relations between the West and Muslims. The task of the community center is to promote cultural and religious harmony through interfaith collaboration, youth and women's empowerment, and arts and cultural exchange. To achieve this goal, the Cordoba House is envisioned to comprise of an auditorium, library, art studio, fitness center, a prayer room, and a memorial for the victims of the September 11 terrorist attacks.

Shortly after the formal project proposal was submitted and endorsed by the Manhattan community board—by a vote of 29-1—the Islamic community center drew extensive political attention, igniting an opposition movement in New York and nationally. Pamela Geller, a New York political activist and blogger, quickly became a chief spokeswoman against the project, appearing on ABC's “Good Morning America,” CNN, NBC Nightly News, and Fox. She argued that the “Monster Ground Zero Mosque” is aimed at Islamic domination and expansionism. In an appearance on CNN's Sunday Morning with Suzanne Malveaux, Geller stated that “building a shrine to the very ideology that inspired the terrorist attacks is an insult to the victims of 9/11,” and claimed that “based on research, four out of five mosques preach hate and preach incitement to violence [7].” Pamela Geller was not the only critic with a national spotlight who displayed a high level of paranoia and intolerance over the Islamic center project. Tea Party Chairman, Mark Williams, described the Islamic community center as a monument that would consist of a mosque for “the worship of the terrorist's monkey-god [8].” Similarly, potential Republican presidential candidate and former House Speaker, Newt Gingrich, claimed that Park51 is “an assertion of Islamist triumphalism,” and part of “an Islamist cultural-political offensive designed to undermine and destroy our civilization [9].”

Perhaps the most audacious depiction of mosques as a breeding ground for hatred and terror emanated from an online video advertisement—“the audacity of Jihad”—sponsored by the National Republican Trust Political Action Committee.4 The advertisement interspersed images of masked militants shooting rifles in the desert along with very disturbing images of the September 11 attack. The narrator made several contentious claims, one being that mosque supporters rejoice in the 9/11 murder. Throughout the video, it is purposely made unclear whether terrorists or American Islamic organizations are sponsoring the building of the Park51 community center.

3.1. Expanding the Scope: Moving Beyond Park51

Over the last year, anti-Islam sentiment and resistance against the construction of mosques has extended from New York to Tennessee and California. In Murfressboro, Tennessee, the growing Muslim population was met with strong opposition against the expansion of an existing Islamic center. After the project managers gained construction approval from Rutherford County, opposition leaders filed a lawsuit in an attempt to halt the construction efforts. During the litigation, the plaintiffs argued that Islam is not a religion and that the center was a conspiracy to impose Sharia law on the United States [10]. Several local residents took to the stand to link the mosque project to the threat of radical Islam. Outside of the courtroom proceedings, local Tea Party activists aggressively fought to stop the mosque by staging numerous protests. Politicians also engaged in the anti-mosque movement. Republican Lieutenant governor, Ron Ramsey, linked Islam to a cult while Republican congressional candidate, Lou Ann Zalenik, claimed that the center is part of “a political movement designed to fracture the moral and political foundation of Middle Tennessee [11].” In addition to expressing anti-mosque attitudes through the court proceedings and protests, the center's construction signs were also vandalized twice and some of its construction equipment set on fire.

In California, two instances of anti-Islam demonstrations that followed the Park51 controversy are noteworthy. In Temecula, a local conservative group called the “Concerned Community Citizens” claimed that a new mosque would clash with Temecula's rural atmosphere, and possibly turn the community of 105,000 into a “haven for Islamic extremists [12].” In an attempt to prevent such plans, the organizers announced a one-hour “singing – praying – patriotic rally” and encouraged participants to bring “Bibles, flags, signs, dogs, and singing voices [13].” And in Yorba Linda, hundreds protested a charity function sponsored by the Islamic Circle of North America (ICNA) to raise money for social programs such as women's shelters, fighting hunger, and homelessness in southern California [14]. The ICNA attendees were met by waving American flags and chants of “No Sharia Law” and “Go back home.” Elected officials such as Republican Congressmen, Ed Royce and Gary Miller, also attended in support of the protest. A key participant, Villa Park Councilmember, Deborah Pauly, who denounced the event as “pure, unadulterated evil,” appeared to even encourage violence towards Muslims. After admitting that she does not care if anyone thinks she is crazy, she announced that she knows “quite a few Marines who will be very happy to help these terrorists to an early meeting in paradise [15].”

Despite the research done by many prominent scholars who suggest religious institutions, including mosques, aid members in fostering skills that promote increased political and civic engagement [16-19], the aforementioned cases clearly illustrate that anti-mosque advocates and many non-Muslim audiences are under the impression that there is something fundamentally different about the mosque. According to some pundits and citizens, Islam is incompatible with democratic American values and mosques are suspicious, dangerous, and even anti-American establishments (e.g., Huntington [20]; Lewis [21,22]).

4. Mosques and Religious Institutions as Sources of Integration

German, Irish, and Italian Catholics faced obstacles to incorporation as newcomers in America— and many faced outright religious discrimination—yet their church ties aided them in engaging in politics [16-18]. Later waves of immigrants also relied on their religious institutions, most notably Jews, Latinos and Koreans, who have integrated more quickly into American life through their religious associations [23]. Scholars such as Eric McDaniel [5] have found churches to be a source of strength and political involvement for African Americans throughout the second half of the 20th century and beyond. Across the political science literature, plethora of research recognizes the role of religious institutions in mobilizing individuals for political participation [24-29]. Since the time of Tocqueville's observations about America, social scientists have long identified a vibrant civil society that was closely related to religiosity and church involvement. Contemporary studies find that in addition to addressing spiritual needs, religious institutions often facilitate members' participation in the political arena. Specifically, religious institutions can be viewed as civic associations [28] that develop basic civic skills, provide information about issues and candidates, and directly recruit members into the political process. Numerous scholars [25,28,30-32] have recognized the church's ability in increasing levels of civic and political involvement by enhancing their members' civic skills, political efficacy, and political knowledge. Places of worship are conduits of civic education and enhance civic skills because they provide a regular meeting place in which individuals interact and discuss public events and affairs [24,27]. In addition to facilitating social networks, religious leaders, such as Catholic and Black Protestant clergy, also play a prominent role in engaging their congregants in the political process by providing cues about salient issues and endorsing candidates, as well as supporting religious interpretations conductive to political participation [5,33-36]. Furthermore, Djupe and Grant [37] find that not only do religious institutions play a vital role in developing social and political skills among their members, churches also directly recruit congregants into the political process. In sum, numerous studies have found a strong link between church attendance and political engagement [26,28,29,38-41].

Legions of books and articles have documented how and why religious institutions are relevant to American politics. However, despite mosques being the fastest growing religious institution in America, many students of American politics know almost nothing about this institution. In 1980 an estimated 745 mosques operated throughout the entire United States, and in 2000 the number had grown to 1,209 – a 62% increase. With this growth and the increased relevance of the Muslim community in America, the role that mosques play in the U.S. is still unsettled and indeed very contentious. Mosques have been celebrated as agents of immigrant incorporation [42] and also called fronts for terrorist organizations [43]. Members of Congress have called on the FBI to increase surveillance of mosques, while Governors have praised Islamic centers for their dedication to America. We argue that mosques, at their core, are religious institutions like churches, cathedrals, and synagogues, and thus, general theories regarding the role that these religious institutions play in American politics should also apply to American mosques. In fact, some empirical research already suggests that mosques promote political and civic engagement. Jamal's [19] examination of Muslim-American political behavior and their levels of mosque involvement in the New York area illustrates that participation in the mosque is accompanied by greater political activity. Added, mosque attendance is positively associated with greater involvement in organizations that help the poor and participation in neighborhood or community groups ([19], p. 531).

Consistent with previous scholarship on the role of religious institutions in American politics, we believe that involvement in the mosque will also foster greater civic and political engagement. Further, we expect the mosque to also create a common identity among American Muslims that emphasizes their shared religious identity and common experiences as a religious minority group in America, thereby moving away from a national origin-based identity. Specifically, through mosque involvement, individuals may show a preference for identifying as Muslim, as opposed to Pakistani or Palestinian.5 While those on the outside may offer uninformed criticism, we also expect Muslims who regularly attend the mosque to view mosques as institutions that facilitate integration into U.S. society as opposed to having an isolating effect.

The proposition, that Islam is compatible with liberal democratic values has been established theoretically by Abdul Rauf [44], Swaine [45], and March [46,47]. March acknowledges that a cursory review of Islamic texts will reveal “prohibitions on submitting to the authority of non-Muslim states, serving in their armies, contributing to their strength or welfare, and participating in their political systems” ([47], p. 236). However, such a conclusion, he notes, would not be based on a comprehensive review of Islamic doctrines, nor would it be based on an in-depth understanding of how Islam is interpreted and practiced by the most devout. Arguments that Islam is not compatible with Western liberal democracies are in fact taken out of context. In contrast, March argues that even pre-modern Islamic legal discourses affirm a certain set of values and principles. Chief among these standards is “the insistence within Islamic jurisprudence on the inviolability of contracts” ([47], p. 236). Because of Islam's commitment to the inviolability of such contracts, March explains that religious Muslims living in the U.S. would expect to follow the principles of the American social contract.

Many Muslim jurists and texts clearly state that it is reasonable for Muslims to reside in non-Muslim societies as long as the non-Muslim society does not prevent the practice of Islam. Through an extensive review of Islamic texts, March concludes that “not only is it permitted to reside in a non-Muslim polity, but also it is permitted to do so while being subject to and obeying non-Muslim law” ([47], p. 243). This obligation is rooted in a religious following of the spirit and letter of Islam. Among Muslims living in the U.S., we should then expect the most religiously devout—those with a high degree of religiosity (tadayyun)—to support and affirm the American social contract, including participation in social, civic and political affairs in America. We offer a significant challenge to the conventional wisdom—religiosity may encourage Muslims to support the American political system.

5. Data and Methodology

To address the issue of compatibility between mosques and civic engagement in America, we implemented a unique study—the Muslim American Public Opinion Survey (MAPOS).6 Scholars familiar with the study of Muslim Americans as well as racial and ethnic politics know well that very little empirical data exists regarding Muslims in America, though this trend is slowly changing in recent years. Thus, we fielded an original survey of Muslim Americans across eleven cities: Seattle, WA, Dearborn, MI, San Diego, CA, Irvine, CA, Riverside, CA, Los Angeles, CA and Raleigh-Durham, NC, Chicago, IL, Dallas, TX, Houston, TX, Washington D.C., and Oklahoma City, OK. The sample represents an incredibly diverse cross-section of American cities and the Muslim population, including interview sites in the East, West, and Midwest, as well as the major Muslim population centers in the U.S. Our sample includes large numbers of Arab, Asian, and African American Muslim respondents, as well as a large mix of foreign-born and U.S. born respondents, making it quite representative of the overall U.S. Muslim population.

The surveys were gathered in an exit-poll style, whereby research assistants handed out clipboards to participants who completed the survey in their own privacy.7 Participants were selected using a traditional skip pattern to randomize recruitment and could choose to answer the survey in English, Arabic, or Persian (Farsi). Naturally, drawing a sample of Muslims in the United States is not easy or efficient given their relatively small population. To address this concern, the survey was implemented at 22 randomly selected locales across the eleven cities. Interviews were gathered either outside community or civic centers where congregational prayers were held for annual Islamic festivals (Eid al-Adha and Eid al-Fitr) or at Friday prayer services at local Islamic centers or mosques.8 In total, 1,410 surveys were completed across the eleven locations, and the demographics of our sample closely match those reported in a recent Pew survey of Muslim Americans (see appendix, Table 1 for sample characteristics).9 We argue that a self-administered survey offers a considerable advantage over a telephone survey because it minimizes any social desirability that might exist among this population. Considerable research has demonstrated that attitudes on sensitive topics are more truthfully given in private self-administered surveys as opposed to telephone surveys [48], and that minorities are likely to moderate their attitudes when being interviewed by whites [49,50]. Thus, for the Muslim American population, a self-administered survey distributed by Muslim research assistants should provide the most accurate data of any mode of collection.

Given that our sample is drawn from religious centers and places of worship, the reader may question if there is any inherent bias in our sample. We are confident for two specific reasons that this is not the case. First, we are actually interested in the more religious Muslim population, given the nature of our research question: do mosques encourage or discourage social and civic participation in American democracy? Scholars, pundits, and journalists who state that the mosque is not compatible often point to the ultra-religious segment of the Islamic population as the source of tension. As we illustrate above, the potential for conflict between Islam and the West is consistently explained by religious dogmatic differences. Thus, it is important that we sample the Muslim population in America that continues to actively practice their religion, as opposed to a sample that is predominantly secularized and assimilated. Second, our sample still demonstrates an appropriate range of religious diversity. While attending the Friday prayer at the mosque and the Eid congregational prayer are descriptively religious practices, they are also cultural and social practices, just as attending Sunday church services or Easter Mass are both religious and cultural events for Christian and Catholic Americans. In response to a question about the importance of religion in their daily life, 50% of our respondents stated religion was very important, 38% stated it was somewhat important, and 12% stated not too important. Likewise, when asked how involved they were with their local mosque, 26% said very active, 40% said somewhat, 20% said not much, and 13% said not at all active. Overall, we are quite confident that our sample provides the appropriate mix of religiously oriented Muslims, but at the same time providing a spectrum of religiosity that ranges from very low to very high. To reiterate, we have many American Muslims in our sample who do not regularly attend the mosque or do not consider themselves very religious.

6. The Findings

We start this section with an analysis of identity among our sample across levels of mosque involvement. Afterwards, for each point below we rely on multivariate regression analysis to predict the degree of integration and civic participation among Muslims in the U.S. Our models build on the general political science literature and include controls for socioeconomic status, political interest and other demographics.10 Our key test is whether or not mosque involvement or religiosity is associated with more, or less political participation and integration in America. For ease of presentation we present the results graphically as predicted probabilities that each outcome will occur.

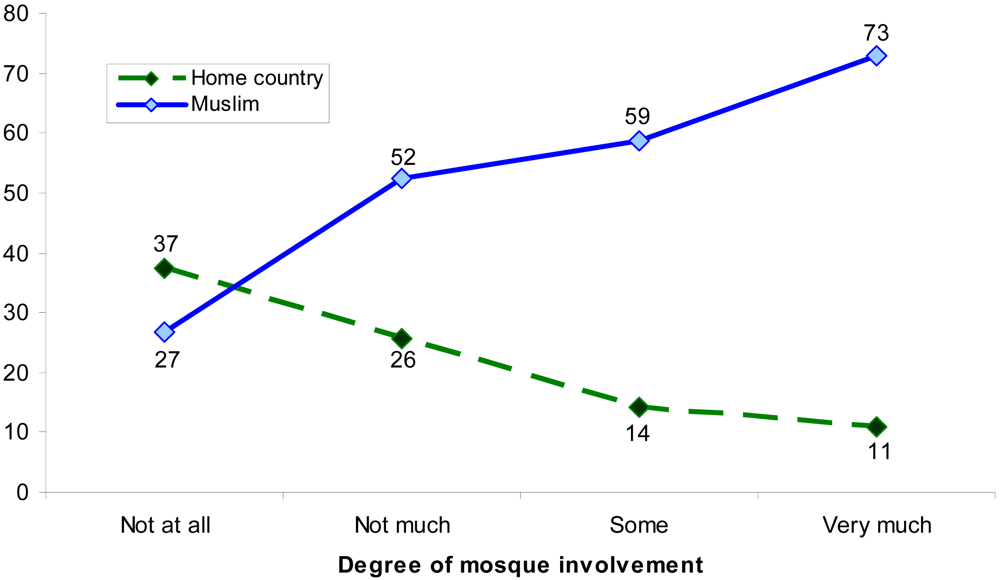

At the low end of the spectrum, out of the respondents who say they are not at all involved or rarely attend their mosque, we find 37% prefer their home country or country of ancestry identity as their primary identity and 27% prefer Muslim (see Figure 2). Home or country of ancestry identity signifies individuals who chose Saudi, Pakistani, Egyptian, Palestinian, Iraqi, Iranian, etc. as their primary means of identity. 11 As mosque involvement increases, we find fewer respondents identify primarily with their home country, and increasing percentages choosing to identify simply as Muslim. Thus, in a way, participation, attendance, and involvement in the mosque may create a new identity for American Muslims in which they identify with a religious-ethnic group, “Muslim” as opposed to national origin country groups. Throughout history, scholars of assimilation and acculturation have noted that shedding a primary identity of the home country was important to integration in America. While national origin identity may remain, we find that American mosques are certainly not encouraging or growing foreign identities, but rather, they are promoting the acceptance of an inclusive and common identity of being Muslim. One possible reason may be the diversity of the mosque in America. In most cities across the United States, only a handful of mosques exist, and most are composed of an incredibly diverse population of American Muslims, with foreign-born, U.S. born, Asian and Arab, and even Sunni and Shia faiths praying side-by-side. The result may be a stronger sense of commonality as a religious and ethnic minority group in the U.S. It is in this context within the U.S. that people now begin to identify themselves not just as Muslims, but as American Muslims. This we believe begins to lay the groundwork for an integrative role for the mosque in American civic life. While the findings do not specifically demonstrate an increase in “American” identity, the movement away from an explicit national origin identity may suggest the adoption of a common minority group label in America. However, the identity as Muslim does not preclude the identity as American, and in fact may compliment it. For example, recent research by Fraga et al. [51] on Latinos, another diverse minority group, has found that support for the pan-ethnic label Hispanic or Latino actually compliments identity as American in the 2006 Latino National Survey. We think a similar process is at work among Muslims, whereby those more involved in the American mosque begin to think more as a common group in America, and the first step is by embracing a common identity as Muslim, as opposed to a national origin identity such as Iraqi or Jordanian.

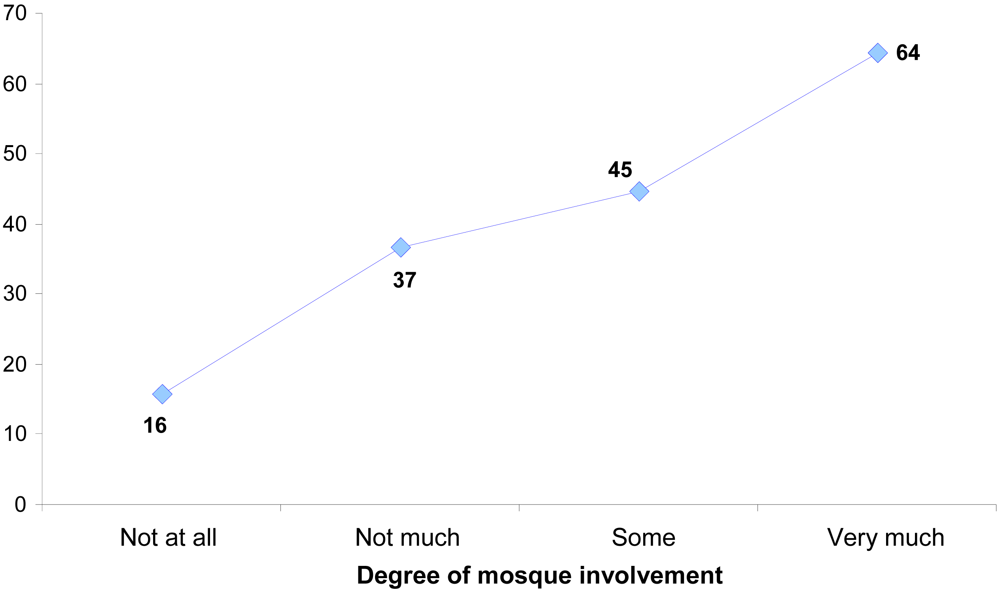

Beyond identity, we noted that mosque involvement should also be related to a strong sense of shared group commonality. We asked respondents if they felt Muslims living in the United States have much in common with each other, and on this point, mosque involvement shows a steady increase in perceptions of group commonality. Among people not at all involved with their mosque, just 16% think they have “a great deal” in common with other American Muslims, however this rate grows to 64% among those who are quite involved with their mosque – a very strong association (see Figure 3). Concepts such as group commonality and linked fate have been shown to be important predictors of political involvement among African Americans and Latinos, and we would expect also the same among Muslim Americans [52,53]. If the mosque is contributing to a stronger sense of group commonality and shared identity, it is also contributing to a group-based resource that encourages civic and political participation.

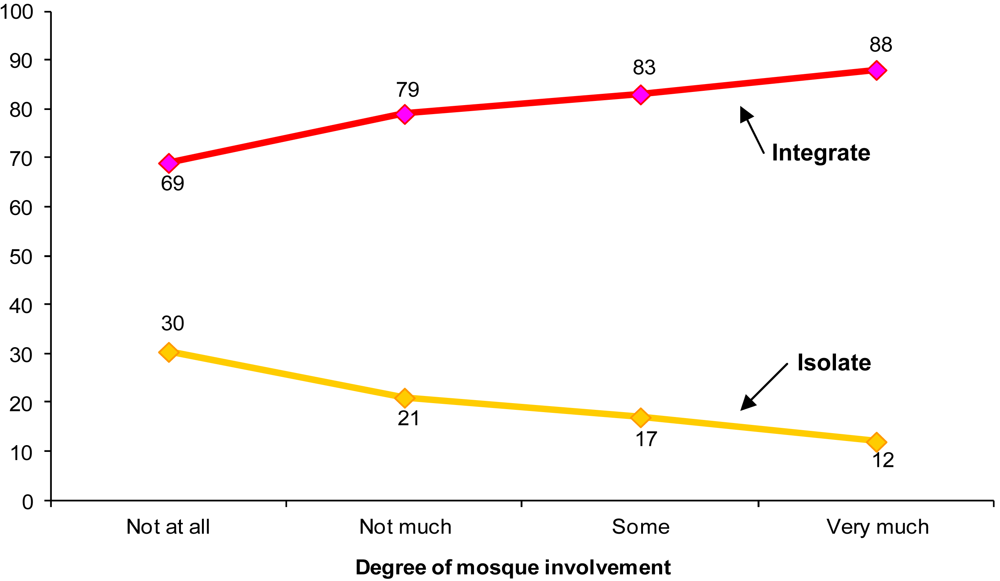

While these ideas of identity, commonality, and group-based resources are important, they are only the foundation of the process in which mosques may be associated with higher levels of integration and participation in American politics. Thus, we also asked respondents whether or not they believed mosques and Islamic centers help Muslims integrate into U.S. society, or keep them more isolated. Once again, we find a strong relationship between mosque involvement and support for integration. Among those who rarely or never attend their mosque, 69% feel mosques help integrate while 30% think they contribute to isolation (see Figure 4). However, as Muslims become more active in their mosque they become more likely to view the mosque as having an integrative effect in U.S. society. A full 88% of those who are very involved in their mosque agree that mosques help integrate as opposed to only 12% who think they contribute to isolation. Despite unfounded claims from those with little knowledge of Islam, we find very clear statistical evidence of a positive association between mosque involvement and support for mosques as centers of social integration in America. This finding is consistent with research on Asian Americans and Latinos, which find newcomers to America to be more quickly integrated and socialized through their churches [54-57].

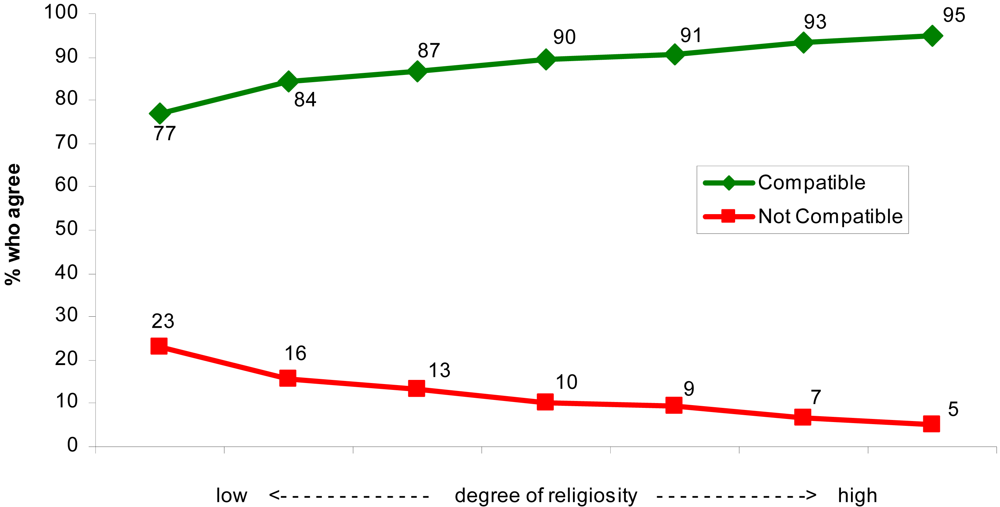

Related to their specific views about mosques and integration in America, we also asked respondents in the MAPOS survey whether or not they thought Islamic teachings were compatible with participation in the American political system. Overwhelmingly we find that American Muslims do see a strong connection and support between Islamic teachings and political participation in the U.S. However, this relationship is strongest among those who are the most religious. We constructed a seven-point religiosity scale by taking into account not only mosque involvement, but a second question on the importance of the Qu'ran and Hadith in daily life. At the lowest end, those who are not at all involved with the mosque and also say religion is not important in their daily life, we find 77% think Islamic teachings are compatible with American politics, and 23% say they are not (see Figure 5). In contrast, at the high end of the spectrum, respondents who are both very involved in their mosque and for whom religion is very important in their daily life, a full 95% say Islamic teachings are compatible with political participation in America.

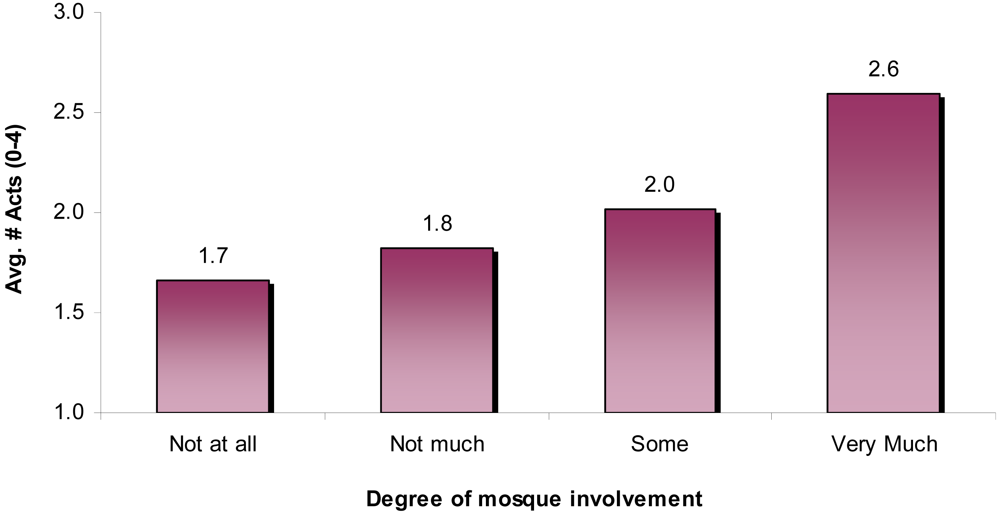

Along similar lines, we find a noticeable increase in the percent who report closely following news about American elections and politics among the most religious, as compared to the least religious. While some may believe that mosques and Islam cause Muslims to turn inwards and shun American society, the data dispels this myth – 81% of the most religious Muslims followed news about American politics closely compared to 70% among the least religious. Finally, we turn directly to measures of political participation using a scale of items which ranges from 0 to 4 that includes attending a community meeting; a rally or protest; writing a letter to a public official; and donation to a political campaign. 12 Similar to Jamal's [19] findings of Muslims in New York, we find in our national dataset that mosque involvement is associated with higher levels of civic participation. On average, those who are very involved in their mosque report 2.6 acts of participation per year, compared to just 1.7 acts among those not at all involved.

7. Conclusions

In the years following 9/11, and most recently since the Park51 Mosque controversy, the loyalties and patriotism of American Muslims have come under considerable scrutiny. Increasingly, Muslims living in the U.S. are being investigated for potential ties to terrorism, and the roles that mosques and Islamic community centers play in America are being questioned. In addition, isolated instances such as the Fort Hood shootings have been used by anti-Islam enthusiasts to link Islam to radicalism and “un-Americanness”. By contrast, in the late 1990s when Eric Rudolph was wanted by the FBI for a series of anti-abortion bombings, his Christian identity and religious motivations for the bombings did not prompt the media to question the loyalties of all Christians, nor did Congress hold hearings investigating Christian churches as breeding grounds of terrorist abortion bombers. It was clearly seen that this was one bad apple and not representative of all Christians.

Despite news headlines often sensationalizing the potential for “homegrown terrorists” there is no systematic data whatsoever to support the claim that mosque involvement or religiosity among American Muslims is associated with anti-American attitudes or behavior. Similar to the negative social construction of post 9/11 Muslim Americans, alarmists in the dawn of World War I and in the aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attacks indiscriminately labeled German and Japanese Americans as “enemies within” and greatly scrutinized their loyalty to the United States. The data reported in this article, collected in 2008 and supported by a research grant from the Social Science Research Council, finally brings reliable evidence to the forefront of debates regarding the role of Islam in America. Based on our careful analysis of our nationally representative survey data, we find that the American Muslim population is middle-class, assimilating quickly, and highly supportive of the American political system—a finding quite consistent with Jamal's [19] analysis of the 2007 Pew study of Muslim Americans. Our findings suggest that an association exists between higher levels of involvement in mosque-related activities and participation in American politics. On a range of political activities such as writing a letter to a government official, donating money to a campaign, or attending a community meeting, those with no connection or involvement to the mosque report an average of 1.7 acts of political participation. In contrast, those who say they are very involved with the mosque report an average of 2.6 political acts per year – a 53% increase. Additionally, while 77% of those with the lowest levels of religiosity feel Islam is compatible with political involvement in America, 95% of those who are most religious indicated Islam is compatible with American politics. Thus, we argue that mosques serve as important religious institutions that are no different than the roles churches and synagogues play in their communities – the role of promoting community involvement and integration into American society.

We should recognize that while there are isolated cases of Muslim individuals who have committed heinous crimes (i.e., Nidal Malik Hassan) similar to Eric Rudolph, they are simply bad apples. Our research findings do not point to any patterns of “Islamic radicalization” inside mosques. Instead, we find that, overwhelmingly, mosques help Muslims integrate into US society, and in fact have a very productive role in bridging the differences between Muslims and non-Muslims in the United States. This is a finding in social science that is consistent with decades of research on other religious groups such as Jews, Protestants and Catholics, where church attendance and religiosity has been proven to result in higher civic engagement and support for the American political system.

Appendix

| MAPOS Study | Pew Study | |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. Born | 38% | 35% |

| Foreign Born | 62% | 65% |

| Non-citizen | 28% | 23% |

| Arab | 51% | 40% |

| Asian | 22% | 20% |

| Black | 11% | 26% |

| White | 8% | 11% |

| Sunni | 61% | 50% |

| Shi'a | 18% | 16% |

| N | 1,410 | 1,050 |

| Independent Vars. | Coef. | S.E. |

|---|---|---|

| Mosque Involvement | 0.534 | (0.081)*** |

| Religious Guidance | 0.579 | (0.060)*** |

| Follow Islam | 0.324 | (0.121)*** |

| English at home | −0.068 | (0.125) |

| Airport Discrimination | 0.165 | (0.127) |

| Sunni | 0.314 | (0.197) |

| Age | 0.121 | (0.092) |

| Income | 0.017 | (0.051) |

| Education | 0.05 | (0.071) |

| Follow News | 0.242 | (0.064)*** |

| Female | 0.046 | (0.150) |

| Arab | 0.180 | (0.292) |

| Asian | −0.018 | (0.256) |

| Black | 0.245 | (0.215) |

| Other Race | −0.114 | (0.369) |

| Foreign Citizen | 0.009 | (0.186) |

| Length | −0.067 | (0.047) |

| Ideology | 0.023 | (0.054) |

| Cut 1 | 0.632 | (0.634) |

| Cut 2 | 3.112 | (0.603) |

| Cut 3 | 5.839 | (0.501) |

| N | 1174 | |

| ML (Cox-Snell) R2 | 0.181 | |

| Pred. Correctly | 56.6 | |

| Prop. Reduction in Error | 21.2 | |

†p < 0.100;*p < 0.050;**p < 0.010;***p < 0.001.

| Independent Vars. | Coef. | S.E. |

|---|---|---|

| Mosque Involvement | 0.256 | 0.088)*** |

| Religious Guidance | 0.134 | (0.203) |

| Follow Islam | 0.028 | (0.163) |

| Muslim Commonality | 0.390 | (0.121)*** |

| English at home | −0.028 | (0.069)*** |

| Airport Discrimination | 0.084 | (0.122) |

| Sunni | 0.001 | (0.153) |

| Age | 0.061 | (0.146) |

| Income | −0.038 | (0.050) |

| Education | −0.139 | (0.090) |

| Follow News | −0.034 | (0.051) |

| Female | 0.001 | (0.176) |

| Arab | 0.157 | (0.313) |

| Asian | −0.054 | (0.135) |

| Black | −0.309 | (0.450) |

| Other Race | −0.327 | (0.410) |

| Foreign Citizen | 0.505 | (0.197)*** |

| Length | −0.013 | (0.084) |

| Ideology | −0.012 | (0.061) |

| Cut 1 | −1.388 | (−0.809) |

| Cut 2 | 0.492 | (1.018) |

| Cut 3 | 2.673 | (0.987) |

| N | 837 | |

| ML (Cox-Snell) R2 | 0.089 | |

| Pred. Correctly | 49.3 | |

| Prop. Reduction in Error | 7.6 | |

†p < 0.100;*p < 0.050;**p < 0.010;***p < 0.001.Dependent variable: “Do you think Islamic centers and mosques help Muslims integrate into USSociety, or keep them more isolated?”*Question was not asked in WA & MI.

| Independent Vars. | Coef. | S.E. | Chg Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muslim commonality | 0.327 | (0.087)*** | 29.9% |

| Mosque: very active | 0.336 | (0.129)** | 12.6% |

| Mosque: not active | 0.307 | (0.183)† | 11.6% |

| Religious Guidance | 0.208 | (0.090)* | 20.5% |

| Follow Islam | 0.167 | (0.093)† | 11.5% |

| Foreign citizen | 0.301 | (0.151)* | 11.0% |

| Second generation | −0.107 | (0.193) | −3.8% |

| Third generation | 0.578 | (0.226)** | 22.2% |

| English at home | 0.178 | (0.131) | 6.5% |

| Airport discrimination | −0.131 | (0.068)* | −9.8% |

| Black | −0.428 | (0.207)* | −14.2% |

| Asian | 0.089 | (0.136) | 3.3% |

| Secular Muslim | −0.031 | (0.156) | −1.1% |

| Shi'a | −0.001 | (0.209) | 0.0% |

| Female | −0.427 | (0.115)*** | −14.9% |

| Age | −0.122 | (0.085) | −12.6% |

| Income | 0.032 | (0.036) | 5.9% |

| College | 0.176 | (0.119) | 6.3% |

| News | 0.173 | (0.063)** | 17.9% |

| Washington | 0.030 | (0.209) | 1.1% |

| California | 0.098 | (0.211) | 3.6% |

| Carolina | 0.212 | (0.211) | 7.9% |

| Length | 0.111 | (0.060)† | 16.4% |

| Constant | −3.298 | (0.469)*** | |

| N | 1,285 | ||

| Chi2 | 129.71 | ||

| % pred correctly | 70% | ||

| Prop reduction error | 13.4% |

†p < 0.100;*p < 0.050;**p < 0.010;***p < 0.001.Dependent variable: agree with the statement, “Islamic teachings are compatible with participation in the American political system”.

| Independent Vars. | Coef. | S.E. | Ch Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muslim commonality | 0.164 | (0.056)** | 51.5% |

| Mosque: very active | 0.285 | (0.079)*** | 36.4% |

| Mosque: not active | 0.017 | (0.119) | 2.1% |

| Religious Guidance | −0.160 | (0.055)** | −65.0% |

| Follow Islam | 0.321 | (0.062)*** | 65.3% |

| Foreign citizen | 0.260 | (0.106)* | 31.5% |

| Second generation | 0.524 | (0.123)*** | 73.5% |

| Third generation | 0.376 | (0.151)* | 51.6% |

| English at home | −0.064 | (0.082) | −7.5% |

| Airport discrimination | 0.071 | (0.047) | 16.2% |

| Black | −0.242 | (0.134)† | −26.2% |

| Asian | −0.239 | (0.090)** | −26.8% |

| Secular Muslim | 0.225 | (0.092)* | 28.7% |

| Shi'a | 0.002 | (0.121) | 0.2% |

| Female | 0.053 | (0.071) | 6.3% |

| Age | 0.056 | (0.053) | 20.6% |

| Income | 0.035 | (0.021)† | 20.9% |

| College | 0.099 | (0.072) | 11.6% |

| News | 0.252 | (0.042)*** | 81.9% |

| Washington | 0.019 | (0.121) | 2.2% |

| California | −0.091 | (0.121) | −10.5% |

| Carolina | −0.310 | (0.132)* | −34.1% |

| Length | 0.046 | (0.037) | 22.4% |

| Constant | −1.773 | (0.300)*** | |

| N | 1,284 | ||

| Chi2 | 245.28 | ||

| Max likelihood R2 | 0.324 | ||

| Cragg and Uhler R2 | 0.334 |

†p < 0.100;*p < 0.050;**p < 0.010;***p < 0.001.Dependent variable is an event count of number of acts of political participation: “During 2006, did you participate in any of these activities: (1) community meeting; (2) rally or protest; (3) write letter to public official; (4) donation to political candidate/campaign”.

References

- World Net Daily. Congressman: Muslims ‘enemy amongst us’. Available online: http://www.wnd.com/?pageId=23257 (accessed on 12 February 2011).

- Politico. Rep. Peter King: There are “too many mosques in this country.”. Available online: http://www.politico.com/blogs/thecrypt/0907/Rep_King_There_are_too_many_mosques_in_this_country_.html# (accessed on 12 February 2011).

- The Huffington Post. Wing, Nick. Peter King: '80 Percent of Mosques in this Country are Controlled by Radical Imams'. Available online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/01/25/peter-king-mosques-radical-imams_n_813878.html (accessed on 29 May 2011).

- C. Panagopolous. “The Polls-Trends: Arab and Muslim Americans and Islam in the Aftermath of 9/11.” Publ. Opin. Q. 70 (2006): 608–624. [Google Scholar]

- E.L. McDaniel. Politics in the Pews: The Political Mobilization of Black Churches. Ann Arbor, MI, USA: University of Michigan Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- R. Putnam, and D. Campbell. American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us. New York, NY, USA: Simon & Schuster, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- A. Tareen. “Pamela Geller and her Ground Zero Mosque Extremists Declare Jihad on Pluralism, Moderates.” Allvoices, Available online: http://www.allvoices.com/contribute-news/6545164-pamela-geller-and-her-ground-zero-mosque-extremists-declare-jihad-on-pluralism-moderates (accessed on 24 February 2011).

- B. Hutchinson. “Tea Party leader Mark Williams says Muslims worship a ‘monkey god’, blasts Ground Zero mosque.” NY Daily News, Available online: http://articles.nydailynews.com/2010-05-19/local/27064852_1_muslims-ibrahim-hooper-ground-zero (accessed on 12 January 2011).

- H. Hertzberg. “Zero Grounds.” The New Yorker. Available online: http://www.newyorker.com/talk/comment/2010/08/16/100816taco_talk_hertzberg (accessed on 12 January 2011).

- L. Johnson. “Judge Refuses to Stop Construction of Tenn.” Mosque. Available online: http://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory?id=12175095 (accessed on 12 February 2011).

- E. Kauffman. In Murfreesboro, Tenn.: Church ‘Yes,’ Mosque ‘No’. Available online: http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,2011847,00.html (accessed on 15 February 2011).

- P. Willon. Planned Temecula Valley mosque draws opposition. Available online: http://articles.latimes.com/2010/jul/18/local/la-me-mosque-20100718 (accessed on 15 February 2011).

- A. Claverie. Temecula: E-mail calls for rally at Islamic center. Available online: http://www.nctimes.com/mobile/article_ee2ccda7-fccc-571b-b917-09574b3e7b1c.html (accessed on 15 February 2011).

- J. Norman. U.S. flags, signs at protest of Muslim event. Available online: http://www.ocregister.com/news/america-288163-fundraiser-wahhaj.html (accessed on 15 February 2011).

- R. Adams. The Ugly face of Islamophobia in Orange County, California. Available online: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/richard-adams-blog/2011/mar/03/orange-county-protest-islam (accessed on 20 March 2011).

- M.M. Gordon. Assimilation in American Life. The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- J.A. Winter. “The Transformation of Community Integration Among American Jewry: Religion or Ethno-religion.” Rev. Relig. Res. 3 (1992): 349–363. [Google Scholar]

- M.E. Odem. “Our Lady of Guadalupe in the New South: Latino Immigrants and the Politics of Integration in the Catholic Church.” J. Am. Ethnic Hist. 24 (2004): 26–57. [Google Scholar]

- A. Jamal. “The Political Participation and Engagement of Muslim Americans.” Am. Polit. Res. 33 (2005): 521–544. [Google Scholar]

- S.P. Huntington. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York, NY, USA: Simon & Schuster, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- B. Lewis. What Went Wrong? Western Impact and Middle Eastern Response. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2002a. [Google Scholar]

- B. Lewis. “What Went Wrong? ” Atl. Mon. 289 (2002): 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- J. Wong, and J. Iwamura. The Moral Minority: Race, Religion and Conservative Politics among Asian Americans. In Religion and Social Justice for Immigrants. Piscataway, NJ, USA: Rutgers University Press, 2007, pp. 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- K. Tate. From Protest to Politics: The New Black Voters in American Elections. New York, NY, USA: Russell Sage Foundation, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- S Verba, K.L Schlozman, and H. Brady. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- A. Calhoun-Brown. “African American churches and political mobilization: The psychological impact of organizational resources.” J. Polit. 58 (1996): 935–953. [Google Scholar]

- K.D. Wald. Religion and Politics in the United States, 3rd ed. Washington, DC, USA: CQ Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- M. Jones-Correa, and D. Leal. “Political participation: Does religion matter? ” Polit. Res. Q. 4 (2001): 751–770. [Google Scholar]

- H McClerking, and E. McDaniel. “Belonging and Doing: Political Churches and Black Political Participation.” Polit. Psychol. 26 (2005): 721–733. [Google Scholar]

- R.D. Putnam. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York, NY, USA: Simon & Schuster, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- T. Skocpol. “Voice and Inequality: The Transformation of American Civic Democracy.” Perspect. Polit. 2 (2004): 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- P.A. Djupe, and C.P. Gilbert. “The Resourceful Believer: Generating Civic Skills in Church.” J. Polit. 68 (2006): 116–127. [Google Scholar]

- F. Harris. “Something within: Religion as a mobilizer of African American political activism.” J. Polit. 1 (1994): 42–68. [Google Scholar]

- J.L. Guth. The Bully Pulpit: The Politics of Protestant Clergy. Lawrence, KS, USA: University Press of Kansas, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- A. Kohut. The Diminishing Divide: Religion's Changing Role in American Politics. Washington, DC, USA: Brookings Institution Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- C.E. Smidt. Pulpit and Politics: Clergy in American Politics at the Advent of the Millennium. Waco, TX, USA: Baylor University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- P.A. Djupe, and T.J. Grant. “Religious institutions and political participation in America.” J. Sci. Stud. Relig. 40 (2001): 303–314. [Google Scholar]

- R.K Brown, and M. Wolford. “Religious Resources and African American Political Actions.” Nat. Polit. Sci. Rev. 4 (1994): 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- J.L. Guth, L.A. Kellstedt, C.E. Smidt, and J.C. Green. Thunder on the Right? Religious Group Mobilization in the 1996 Election. In Interest Group Politics. Edited by A.J. Cigler, and B.A. Loomis. Washington, DC, USA: Congressional Quarterly Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- C. Smidt. “Religion and civic engagement: A comparative analysis.” Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 565 (1999): 176–192. [Google Scholar]

- R.K Brown, and R.E. Brown. “Faith and Works: Church-Based Social Capital Resources and African-American Political Activism.” Soc. Forces 82 (2003): 617–641. [Google Scholar]

- H.R. Ebaugh. Religion and the New Immigrants. In Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Edited by M. Dillon. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- D. Temple-Raston. “Mosque Attendance Falls after Terrorism Arrests.” National Public Radio, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- F. Abdul Rauf. What's Right with Islam: A New Vision for Muslims and the West. San Francisco, CA, USA: Harper San Francisco, 2004, p. 86. [Google Scholar]

- L. Swaine. “Institutions of Conscience: Politics and Principle in a World of Religious Pluralism.” Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 6 (2003): 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- A. March. “Liberal Citizenship and the Search for an Overlapping Consensus: The Case of Muslim Minorities.” Philos. Public Aff. 34 (2006): 373–421. [Google Scholar]

- A. March. “Islamic Foundations for a Social Contract in non-Muslim Liberal Democracies.” Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 101 No. 2. (2007). [Google Scholar]

- M. Krysan. “Privacy and the Expression of White Racial Attitudes: A Comparison across Three Contexts.” Public Opin. Q. 62 (1998): 506–544. [Google Scholar]

- M. Krysan, and M.P. Couper. “Race in the Live and Virtual Interviewer: Racial Deference, Social Desirability, and Activation Effects in Attitude Surveys.” Soc. Psychol. Q. 66 (2003): 364–383. [Google Scholar]

- D. Davis. “The Direction of Race of Interviewer Effects among African-Americans: Donning the Black Mask.” Am. J. Polit. Sci. 41 (1997): 309–322. [Google Scholar]

- L.R. Fraga, J.A. Garcia, G.M. Segura, M Jones-Correa, R Hero, and V. Martinez-Ebers. Latino Lives in AMERICA: Making it Home. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Temple University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- M.C. Dawson. Behind the Mule: Race and Class in African-American Politics. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- G.R. Sanchez. “The Role of Group Consciousness in Political Participation Among Latinos in the United States.” Am. Polit. Res. 34 (2006): 427–450. [Google Scholar]

- P Lien, M Conway, and J. Wong. The Politics of Asian Americans. New York, NY, USA: Routledge, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- M.A. Barreto, and D. Bozonelos. “Democrat, Republican, or None of the Above? The Role of Religiosity in Muslim American Party Identification.” Polit. Relig. 2 (2009): 220–229. [Google Scholar]

- J.H. Kim. Bridge-makers and Cross-Bearers: Korean-American Women and the Church. Atlanta, GA, USA: Scholars Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- J. Gomez-Quinones. Chicano Politics: Reality and Promise 1940-1990. Albuquerque, NM, USA: Univ. of New Mexico Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 1Using the Lexis-Nexis newspaper search of newspapers in the United States, we searched for the terms: (Muslim American or American Muslim) within 1 word of (radical! or jihad! or terror! or threat! or extremis!) and grouped data in 12 month periods from April to April across years.

- 2The “Radicalization of Islam” hearings began on March 10, 2011.

- 3Community Board No. 1 is the council that represents a corner of Manhattan that includes both Park51 and the 9/11 site. The Cordoba House Project was introduced in the Financial Committee.

- 4This ad has received close to 400,000 views on YouTube alone.

- 5As opposed to mosques in the Middle East and Asia, mosques in the United States are much more diverse and multi-ethnic in nature, whereby immigrants from Pakistan, Egypt and Turkey might all attend and worship in the same mosque. Because there are relatively fewer mosques in the United States, Muslims are much more likely to mix along ethnic lines in America, perhaps contributing to a shared identity.

- 6For more info, please visit the MAPOS website at: http://www.muslimamericansurvey.org.

- 7Research assistants were themselves Muslim, predominantly second generation, most fluent in a second language (Arabic or Urdu) and were balanced between men and women. All research assistants attended two training sessions and participated in a pilot survey to ensure consistency and professionalism.

- 8Our survey was in the field from December 30, 2006 to December 9, 2008. Of the 1,410 completed interviews, 373 were collected during Eid al Adha prayers, 726 during Eid al Fitr prayers, and 311 were collected during Jum'ah (Friday) prayers.

- 9The Pew survey was conducted by telephone, and went into the field at roughly the same time as our survey.

- 10Full regression models are detailed in the appendix, tables 2-5.

- 11Other options include: Lebanon, Syria, Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia, America, Jordan, Europe, Morocco, India, Turkey, and Other.

- 12We also asked if respondents had voted in the prior November election. However not all respondents were registered to vote, or U.S. citizens. Thus, in this analysis we limit our scale of political participation to include activities that all respondents could have participated in.

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Dana, K.; Barreto, M.A.; Oskooii, K.A.R. Mosques as American Institutions: Mosque Attendance, Religiosity and Integration into the Political System among American Muslims. Religions 2011, 2, 504-524. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel2040504

Dana K, Barreto MA, Oskooii KAR. Mosques as American Institutions: Mosque Attendance, Religiosity and Integration into the Political System among American Muslims. Religions. 2011; 2(4):504-524. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel2040504

Chicago/Turabian StyleDana, Karam, Matt A. Barreto, and Kassra A.R. Oskooii. 2011. "Mosques as American Institutions: Mosque Attendance, Religiosity and Integration into the Political System among American Muslims" Religions 2, no. 4: 504-524. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel2040504

APA StyleDana, K., Barreto, M. A., & Oskooii, K. A. R. (2011). Mosques as American Institutions: Mosque Attendance, Religiosity and Integration into the Political System among American Muslims. Religions, 2(4), 504-524. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel2040504