1. Introduction

Narrative mural paintings were widespread in Buddhist temples from an early period and played a crucial role in transmitting Buddhist beliefs and ideas among lay audiences in China. In recent years, scholars have increasingly focused on the connections between religious art and vernacular narratives, both of which represent popular dimensions of Chinese Buddhism. Until recently, however, such studies concentrated primarily on medieval materials, particularly the relationship between mural paintings in the Dunhuang cave temples and the vernacular texts discovered there in 1900 (e.g.,

Mair 1989;

Wei 2023).

Nevertheless, narrative subjects remained an important component of Buddhist temple decoration in later periods, especially during the Ming dynasty. Several studies have already noted close links between the subjects of Buddhist wall paintings from the early sixteenth century and textual narratives found in

baojuan (precious scrolls), a type of prosimetric literature designed for oral performance that flourished between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. Notable examples include illustrations of the story of Prince Golden Calf in the Buddha Hall of the Vairochana Monastery (Piludian 毗盧殿) near Shijiazhuang in Hebei (ca. 1515) and murals depicting the story of Princess Miaoshan 妙善 in the Hall of Great Compassion (Dabeidian 大悲殿) of the Monastery of Great Wisdom (Dahuisi 大慧寺) in Beijing (constructed ca. 1513) (e.g.,

Zhang and Tian 2012;

Zhang and Guo 2018;

Berezkin 2017a). Although these cases demonstrate a clear affinity with the

baojuan narratives, the extant textual versions—

Baojuan of the Prince Golden Calf (

Jin niu taizi baojuan 金牛太子寶卷) and

Baojuan of Xiangshan (

Xiangshan baojuan 香山寶卷)—date to a much later period than the murals themselves.

1 This discrepancy is likely due to the poor state of preservation of Ming-dynasty vernacular literature, as many early versions of popular narratives have not survived.

This article addresses an even earlier example of such connections between popular Buddhist narratives and temple painting: the mural on the rear wall of the Vairochana Hall (Piludian 毗盧殿) of Guanyin Monastery (Guanyinsi 觀音寺) in Xinjin 新津 County, Sichuan (near Chengdu), called the “Complete Hall (or Picture) of Xiang [Incense] Mountain” (Xiangshan quan tang 香山全堂).

2 This impressive mural, covering a total area of approximately nineteen square meters, bears two dedicatory inscriptions indicating that it was originally completed in 1468 and renovated in 1756.

3 As a firmly dated example of Ming-dynasty narrative murals, it is of exceptional importance. To the best of my knowledge, it represents the earliest securely dated visual representation of the Miaoshan story in China, but has received relatively little scholarly attention to date.

The story of Miaoshan—the female incarnation of Bodhisattva Guanyin (Guanshiyin, Skt. Avalokitêśvara)—is an apocryphal Chinese Buddhist narrative that promotes the possibility of women’s spiritual cultivation. Emerging in northern China around the twelfth century, it became a famous subject in vernacular literature and has long attracted the attention of both Chinese and international scholars.

4 Most studies, however, have focused on its textual transmission,

5 while its pictorial representations have received comparatively little analysis, particularly in English-language scholarship. For example, in her influential study of the history of Guanyin beliefs in China, Professor Chün-fang Yü examined both textual sources and visual images of Guanyin, including depictions of the Miaoshan story, but the visual material she discussed was relatively limited (

Yü 2001, pp. 349–50). To date, no comprehensive study of early Miaoshan illustrations exists in Chinese scholarship either.

Although Chinese scholars have proposed interpretations of the Xinjin Miaoshan mural based on popular literary sources from the late imperial period, no systematic analysis has yet been conducted that situates this mural within the full range of available textual and visual evidence.

6 Existing studies generally argue that the Xinjin mural’s content derives from the

Baojuan of Xiangshan, particularly as represented by the 1773 reprint edition (e.g.,

Li and He 2012;

Li and Zhang 2012;

Liu and Yang 2014, pp. 70–78;

Ma 2018). I consider the relationship between the visual and textual traditions much more complex. It is difficult to identify a single textual source that the Xinjin mural follows in its entirety. By comparing the mural with several early textual versions of the Miaoshan story—most importantly, a recently rediscovered version of the

Baojuan of Xiangshan that can be dated approximately to the same period—this study highlights the distinctive features of the Xinjin mural and demonstrates the multifaceted interactions between Buddhist painting and vernacular performance literature in Ming China.

7 In addition, the mural is contextualized within the broader history of Ming-dynasty visual representations of the Miaoshan story.

2. The Miaoshan Story Mural in Guanyin Monastery, Xinjin

This section provides an overview of the Miaoshan story mural at Guanyin Monastery in Xinjin, summarizing its narrative content and highlighting its historical and cultural significance. Guanyin Monastery in Xinjin is a well-known site in the history of Ming-dynasty Buddhist art. According to stele inscriptions preserved at the site—most notably “The Stele Record of the Rebuilding of the Guanyin Monastery on Jiulian [Nine Lotuses] Mountain of Pinggai Circuit” (九蓮山平蓋治觀音寺重修碑記), dated 1490—this monastery was originally founded at the end of the twelfth century (

Fang and Che 2013, p. 466). The stele records that the monastery was first constructed during the Chunxi 淳熙 reign period of the Southern Song (1174–1189).

8The same source indicates that the Guanyin Monastery was destroyed during the warfare accompanying the Yuan–Ming transition in the fourteenth century. In 1432, Buddhist monks initiated a large-scale reconstruction project. Based on the epigraphical evidence collected at the site, modern scholars have reconstructed the history of Guanyin Monastery, concluding that rebuilding took place between 1432 and 1490, with later additions of sculptural works continuing until 1555 (

Fang and Che 2013, pp. 7–8; see also

Ma 2018, pp. 8–10). The monastery was constructed primarily through donations from the local elite, although its monks also maintained connections with Beijing monasteries that enjoyed imperial patronage (

Fang and Che 2013, p. 466). The exceptionally high artistic quality of the Xinjin temple decorations further suggests that the monastery received court support, a common phenomenon during the Ming dynasty, and that artists from the capital may have participated in its construction during the fifteenth century (

Li and He 2012, pp. 124–25).

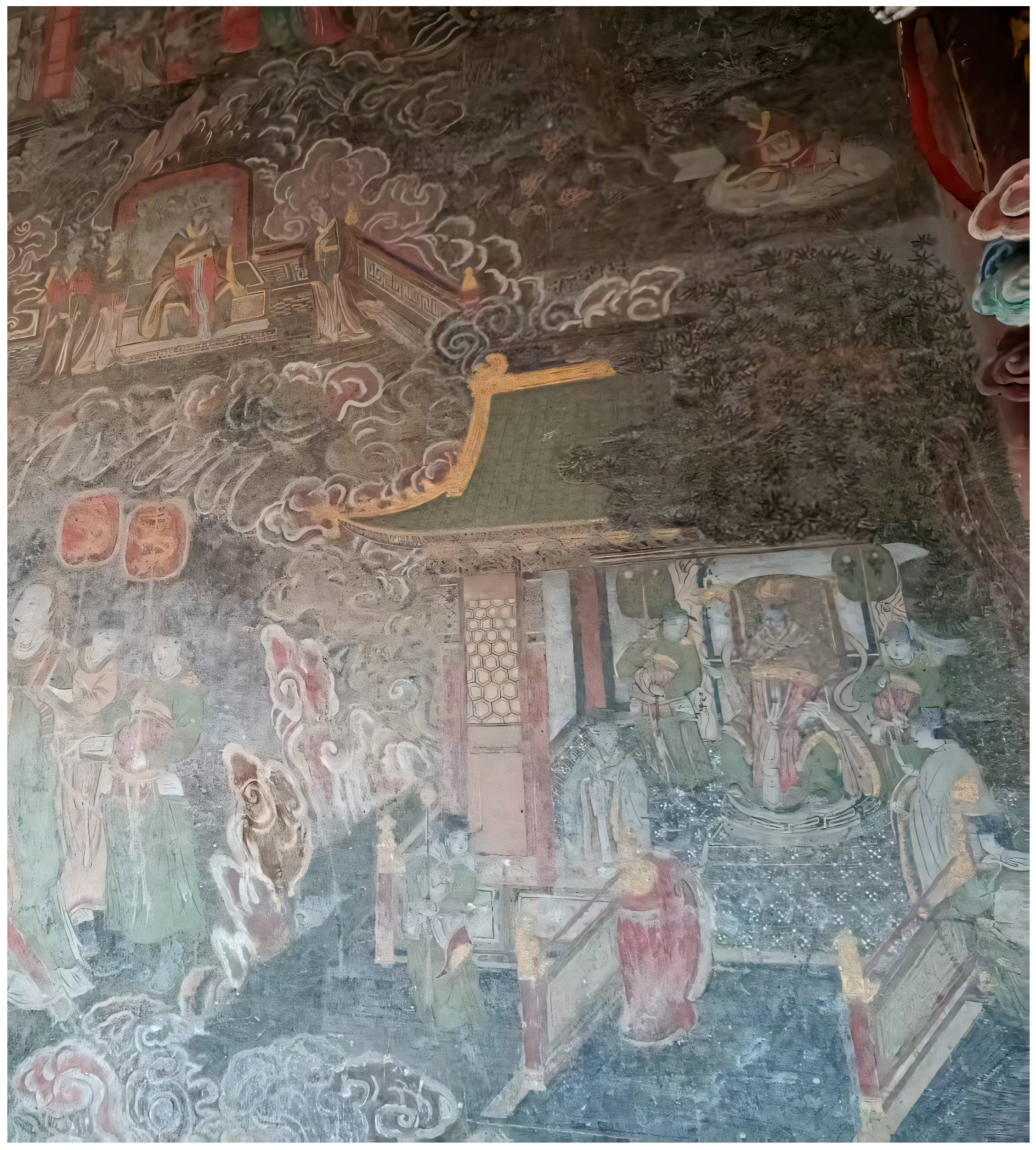

Guanyin Monastery is particularly renowned for its extensive mural paintings, most of which are concentrated in the Vairochana Hall, built between 1462 and 1466. This hall contains sculptural representations of the Buddha’s three bodies, accompanied by attendants, as well as murals depicting the “Twelve Perfected Ones” (Shier yuanjue 十二圓覺) and “Twenty-Four Heavens” (Ershisi tian 二十四諸天) (

Fang and Che 2013, pp. 7–120). Numerous donor portraits, representing local officials and members of their families, attest to the substantial contributions of the regional elite. The Miaoshan story mural—known as the “Complete Picture of Xiang Mountain”—is located on the rear wall behind the main altar of the Vairochana Hall.

9 Its narrative scenes are arranged in a circular composition surrounding a seated image of Thousand-armed Guanyin.

The Xiang Mountain mural depicts the spiritual journey of Princess Miaoshan, who refuses the marriage arranged by her father, King Miaozhuang, and, after enduring a series of severe trials, ultimately attains enlightenment and transforms into the powerful Bodhisattva of Compassion. Ordered to be executed by her father, Miaoshan miraculously survives, resumes her spiritual cultivation on Xiang Mountain, and eventually cures King Miaozhuang of a grave illness sent by Heaven as retribution for his misdeeds. Through this act of compassion, she also leads him to conversion to Buddhism. The narrative gained widespread popularity in China because it reconciled Buddhist doctrines with the Confucian ideal of xiao 孝 (filial piety), a theme frequently emphasized in Chinese Buddhist literature.

The Xinjin Miaoshan mural is a fine-line painting that employs a wide range of bright pigments and incorporates gilded details produced with the costly technique of “splashing gold paste” (

li fen tie jin 瀝粉貼金) (see

Fang and Che 2013, pp. 20–21;

Li and He 2012, pp. 125–26). This technique, though expensive, appears frequently in Ming-dynasty Buddhist murals in Sichuan, reflecting the considerable financial investment made by the local patrons in temple construction (

Zeng 2016, pp. 124–62).

At the center of the mural, Guanyin is depicted seated on a lotus throne (

Figure 1). With forty-two arms—most bearing an eye painted in the palm—this image conforms to the classical iconography of the Thousand-handed and Thousand-eyed Guanyin, a form that became widespread in central China from the Tang dynasty onward (

Yü 2001, pp. 263–92). The deity is shown with three faces and a crown surmounted by six Buddha heads, consistent with mainstream Chinese Buddhist iconographic conventions (

H. Wang 1994;

Feng 1996). The ritual implements held in Guanyin’s hands—including a Buddha’s image, fan, precious bowls, lotus flower, vajra, mirror, sword, and rosary—are grounded in the scriptural tradition. Such attributes appear in the Tantric texts promoting the Thousand-handed form of Guanyin, including the

Dharani of the Thousand-handed and Thousand-eyed Bodhisattva Guanyin of Great Compassionate Heart (千手千眼觀世音菩薩大悲心陀羅尼, translated by Bukong [Amoghavajra] 不空, 705–774, T. 1064), the

Dharani of the Thousand-handed and Thousand-eyed Bodhisattva Guanyin of Broad and Complete Unobstructed Great Compassionate Heart (千手千眼觀世音菩薩廣大圓滿無礙大悲心陀羅尼經, translated by Qiefandamo [Bhagavadharma] 伽梵達摩, T. 1060), and the Body Scripture-Dharani of the Thousand-handed and Thousand-eyed Bodhisattva Guanyin 千手千眼觀世音菩薩姥陀羅尼身經, translated by Putiliuzhi [Bodhiruci] 菩提流志, T. 1058), among others (

Qian shou qian yan 1983a;

Qian shou qian yan 1983b;

Qian shou qian yan 1983c; see also

Yü 2001, pp. 59–68). As the present study focuses primarily on the surrounding narrative scenes rather than on the Guanyin iconography itself, this central image will not be discussed further here.

I identify twenty-three narrative scenes illustrating the hagiography of Guanyin in the Xinjin mural (

Figure 2).

10 These scenes follow an approximate chronological order, beginning at the lower right, progressing upward, then continuing from the lower left and ascending once more toward the top. This sequence, however, is not entirely linear, and a full reconstruction of the pictorial narrative requires careful comparison with written versions of the Miaoshan legend, particularly various recensions of the

Baojuan of Xiangshan. Chinese scholars Liu Xiancheng and Yang Xiaojin divided the mural into twenty-one scenes,

11 while Ma Jidong identified four additional episodes.

12 Based on a comparison with two early versions of the

Baojuan of Xiangshan, I propose an alternative scheme for interpreting the mural’s narrative structure, differing from previous studies. Some scenes, nevertheless, remain difficult to identify with certainty.

The narrative begins with King Miaozhuang consulting his officials regarding the issue of succession (Scene 1). Lacking male heirs—a serious concern in traditional Chinese society—he seeks to arrange marriages for his daughters in order to secure grandsons. In Scene 2, the king announces his marriage plans to his daughters (

Figure 3). While the two elder princesses accept his decision,

13 Miaoshan refuses, expressing her desire to pursue spiritual cultivation and to transcend the cycle of death and rebirth. Scene 3 depicts Miaoshan being confined to the rear garden as a punishment for disobedience. In Scene 4, her elder sisters, now living comfortably with their husbands, visit her in the garden trying to persuade her to accept marriage (

Figure 4).

In Scene 5, King Miaozhuang personally visits Miaoshan in an attempt to make her to change her mind. Scene 6 shows Miaoshan once again rejecting her father’s proposal and urging him to return to the palace. In Scene 7, she pays her final respects to her father before departing for the Convent of White Sparrows (Baiquesi 白雀寺), where she intends to become a nun. Scene 8 portrays divine beings assisting Miaoshan in completing the arduous labor assigned to her by the abbess of the convent, who had imposed these tasks at King Miaozhuang’s request in an effort to deter Miaoshan from monastic life. Scene 9 depicts the burning of the convent, ordered by King Miaozhuang after the abbess fails to persuade Miaoshan to abandon her decision (

Figure 5).

Scenes 10 through 14 depict the execution of Miaoshan following her miraculous escape from the fire. Scene 10 shows the proclamation of the king’s order before a specially constructed “painted tower” (cai lou 彩樓). In Scene 11, Miaoshan’s parents and sisters attempt one final persuasion before she is led to the execution ground. Scene 12 depicts an unsuccessful attempt to behead Miaoshan with a sword. In Scene 13, she is strangled with a bowstring; this scene is severely damaged and visible only in outline. Scene 14, also poorly preserved, shows Miaoshan’s body being carried away by a tiger.

In Scene 15, Miaoshan descends to the underworld accompanied by a youth “dressed in green” (qing yi tongzi 青衣童子) and appears before King Yama (Yanluo-wang 閻羅王), lord of the netherworld. Scene 16 shows Miaoshan’s return to the human world by the Yama’s decree, where she finds herself in a mountainous wilderness threatened by a great dragon. In Scene 17, the Deity of the Star of Great Whiteness (Taibai xing 太白星, i.e., Venus), disguised as an elderly man, descends to rescue her. Scene 18 depicts Miaoshan’s journey to Xiang Mountain, accompanied by the celestial emissaries and earth god of the locality (

tudi 土地).

14In Scene 19, Miaoshan reappears at court in the guise of a monk to cure her father’s grave illness. She declares that the only effective medicine must be made from the hands and eyes of a close relative and advises the king to seek the assistance of a hermit living on Xiang Mountain. Scene 20 shows the king’s envoy traveling to Xiang Mountain to request the hermit’s hands and eyes after Miaoshan’s elder sisters refuse to offer their own (

Figure 6). Scene 21 depicts the envoy’s return to the palace with the donated hands and eyes. In Scene 22, King Miaozhuang, accompanied by his queen

15 and retinue, journeys to Xiang Mountain to express gratitude, where he recognizes the enlightened hermit as his daughter. Following his conversion to Buddhism, Miaozhuang is reborn in heaven after death.

Scene 23 has been interpreted by some Chinese scholars as representing “the mother-queen and daughter building the boat of salvation” (母女修普渡船), although this reading is questionable (

Liu and Yang 2014, p. 75;

Ma 2018, p. 22).

16 No corresponding episode can be identified in textual sources from a comparable period. The scene depicts two female figures: one carrying firewood on her shoulders and another standing nearby with a guiding gesture (

Figure 7). I suggest that this image may instead relate to Miaoshan’s arduous labor at the Convent of White Sparrows (Scene 8), with divine assistance offered by Guanyin in female form, a motif commonly found in Buddhist miracle narratives.

The royal figures flanking Thousand-armed Guanyin in the Xinjin mural should be identified as Miaoshan’s parents, King Miaozhuang and Queen Baode, together with her two elder sisters and their retinues. At the base of Guanyin’s lotus throne appear images of the Four Heavenly Kings (tianwang 天王), major protective deities in Buddhism. A small female donor figure is also visible behind Miaoshan’s elder sisters (

Figure 8), likely representing the principal female patron mentioned in the 1468 dedicatory inscription.

Here a few words must be said about the historical background and religious function of the Xiangshan mural in Xinjin. The dedicatory inscriptions associated with the Xiangshan mural provide valuable insight into its historical and cultural context, despite their damaged condition. Of particular significance is the 1468 inscription, which names a woman as the principal sponsor of the mural (her surname is undiscernible now), together with several of her children. This suggests that the mural’s patronage should be understood as an expression of gendered Buddhist devotion. The association of the Miaoshan story with female believers is unsurprising, as the narrative affirms the possibility—and even necessity—of women’s participation in Buddhist religious practice (mostly talking about women of elite classes) (

Dudbridge 2004, pp. 102–6;

Yü 2001, pp. 333–38). The gendered nature of this devotion is further underscored by the concluding phrase of the inscription: “All of them wish to broadly plant merit in this life, so that they may be reborn as men in the next existence” (眾願今生廣種福X, 來世轉成男).

17 Such sentiments were commonplace in Chinese Buddhist literature and appear frequently in the popular sutras as well as Ming-dynasty precious scrolls.

18 A second inscription records the names of six women who contributed to the mural’s renovation in 1756, further confirming the enduring role of female devotion in the history of this site.

The primary function of the Xiangshan mural in Xinjin was to illustrate miracles associated with the cult of Guanyin. As such, it exemplifies a longstanding tradition in Chinese Buddhist art of combining iconic and narrative imagery, a practice evident since the Tang (618–907) and Song (960–1279) dynasties.

19 Pictorial images of Guanyin produced in these periods were often surrounded by depictions of miraculous responses derived from the “Pumen pin” (普門品, Chapter of the Universal Gates [of Salvation]) of the famous

Lotus Sutra (妙法蓮花經, T. 262), which later circulated independently as the

Sutra of Guanyin (

Guanyin jing 觀音經) (

Yü 2001, pp. 75–77). This compositional pattern is well attested in the Tang-dynasty murals of the Mogao caves at Dunhuang (e.g., caves 45 and 205, see

Zhongguo Dunhuang bihua quan ji 2006, vol. 6, pp. 49, 64–65; vol. 7, p. 42). In the Xinjin mural, however, scenes from the Miaoshan story appear to replace these earlier miracle narratives. This substitution also reflects the historical association between the Thousand-armed Guanyin and the Miaoshan legend, which is well documented in sources from the twelfth—thirteenth centuries (

Dudbridge 2004, pp. 5–20, 38–41). As Chün-fang Yü has argued, the Miaoshan narrative originally served the domestication of the Tantric Thousand-armed Guanyin image within the Han Chinese cultural context (

Yü 2001, pp. 312–15, 348–49). It was therefore entirely logical for the patrons and monks of Guanyin Monastery to draw upon this popular hagiography when commissioning the Xinjin mural.

Guanyin devotion had been widespread in Sichuan since an early period, and historical sources attest to the presence of murals depicting Guanyin in Sichuanese temples during the Tang and Song dynasties.

20 These early images (that mostly did not survive) presumably were not accompanied by scenes from the Miaoshan story. The appearance of Miaoshan episodes in the Xinjin mural of Xiangshan—the earliest known visual representations of this narrative—must therefore be understood in relation to the growing popularity of the Miaoshan story during the Ming dynasty, particularly through the dissemination of

baojuan (precious scrolls).

3. The Miaoshan Mural from Xinjin and Two Early Versions of the Baojuan of Xiangshan

To identify the narrative source of the Xinjin mural of Xiang Mountain, it is necessary to compare it with contemporaneous textual versions of the Miaoshan story. Previous Chinese scholarship has generally proposed that the most likely source of the Xinjin mural was the

Baojuan of Xiangshan (

Li and He 2012, pp. 123–24;

Liu and Yang 2014, pp. 77–78). Among extant narratives, the

Baojuan of Xiangshan offers the most detailed account of the Miaoshan story and was already circulating by the time the mural was produced (

Che 2009, pp. 90–95). The difficulty lies in the fact that two major early versions of this text survived only in the eighteenth-century printed editions.

Liu Xiancheng and Yang Xiaojin, as well as Ma Jidong in his MA thesis, primarily relied on the recension of the

Baojuan of Xiangshan printed in Hangzhou by the sutra store of Zhaoqing Monastery (昭慶大字經房) in 1773 (

Liu and Yang 2014, pp. 77–78;

Ma 2018, pp. 15–38). This edition, now held in a private Japanese collection, is hereafter referred to as the Hangzhou recension. The woodblock text was reprinted and studied by its owner, Yoshioka Yoshitoyo 吉岡義豊 (1916–1979) (

Yoshioka [1971] 1990, vol. 4, pp. 245–405). The Hangzhou recension bears the full title of the

Scripture of the Previous Life of the Bodhisattva Guanshiyin (

Guanshiyin pusa ben xing jing 觀世音菩薩本行經) and attributes authorship to the monk Puming 普明 of the Upper Tianzhu Monastery (Shang Tianzhusi 上天竺寺) in Hangzhou (ca. early twelfth century). Although most scholars of

baojuan have questioned such an early date, the Hangzhou recension has long been treated as the earliest extant version of this precious scroll, dating back to around the beginning of Ming dynasty (e.g.,

Dudbridge 2004, p. 52;

Overmyer 1999, pp. 45–46;

Yü 2001, pp. 317–20;

Idema 2008, p. 31;

Che 2009, p. 113).

However, the earliest surviving recension of the

Baojuan of Xiangshan is represented by a reprint produced in 1772 at the Temple of Repaying Mercies (Báo Ân tự 報恩寺) in Hanoi under the supervision of the monk Hải Khoát 海濶. This unique copy is now preserved at the Institute of Sino-Nom Studies of the Vietnamese Academy of Social Sciences and is hereafter referred to as the Hanoi recension. According to its colophon, this edition reproduces a woodblock text entitled

Precious Scroll of Incense Mountain of the Bodhisattva Guanshiyin of Great Compassion (

Dabei Guanshiyin pusa Xiangshan baojuan 大悲觀世音菩薩香山寳卷), originally printed in Nanjing by Chen Longshan’s scripture store (陳龍山經房) and datable to the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century (

Berezkin and Riftin 2013, pp. 450–59).

Notably, neither the main text nor its three prefaces—two of which were certainly written in Vietnam,

21 and one possibly inherited from the original Chinese edition—attributes the text to Puming. Instead, the third preface (presumably originating in China) refers to the

Life of the Bodhisattva of Great Compassion of Xiangshan (

Xiangshan da bei pusa zhuan 香山大悲菩薩傳, ca. 1099) by the Song-dynasty scholar-official Jiang Zhiqi 蔣之奇 (1031–1104) as the narrative basis of this precious scroll. As Jiang’s work is widely recognized as the earliest known written account of the Miaoshan legend, this attribution aligns closely with modern reconstructions of the history of this narrative (

Dudbridge 2004, pp. 5–20).

For a long time, the Hanoi recension of the

Baojuan of Xiangshan was basically forgotten in China, aside from several late manuscript copies used in local ritual contexts that have recently been discovered in southwestern China (

Berezkin and Riftin 2013, pp. 459–61;

Hou 2018, pp. 44–45). As a result, it was unknown to most Western and Chinese scholars of precious scrolls until relatively recently. Comparative analysis of the Hanoi and Hangzhou recensions indicates that the former preserves a more archaic text in terms of narrative structure, content, and ritual features. Although both versions share the same basic storyline, the Hanoi recension includes fewer narrative episodes and less elaboration, while featuring extensive introductory and concluding sections and a rigid alternation of prose and verse, typical of early

baojuan from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. On this basis, it has been proposed that its core narrative may date to this early period (

Berezkin and Riftin 2013, pp. 465–66). At the same time, stylistic and structural features of the Hangzhou recension also suggest composition before the end of the Ming dynasty (sixteenth century).

Having access to both recensions, I compared them in detail with the Xinjin mural. The mural includes several episodes that appear in both versions of the

Baojuan of Xiangshan, such as strangulation of Miaoshan with the bowstring before her descent into the underworld and the intervention of the deity of the Venus planet after her resurrection. These narrative details are absent from earlier written accounts of the Miaoshan legend, including Jiang Zhiqi’s

Life of the Bodhisattva of Great Compassion of Xiangshan and the

Life of the Mahāsattva Guanyin (

Guanyin dashi zhuan 觀音大士傳), attributed to Guan Daosheng 管道昇 (1262–1319), female author and artist (see

Dudbridge 2004, pp. 21–35, 44–46, 119–33). Their presence in the mural therefore strongly suggests derivation from the

Baojuan of Xiangshan or closely related vernacular narratives.

The crucial question, however, is whether any surviving baojuan text corresponds exactly to the narrative depicted in the Xinjin mural. At first glance, many details appear to align more closely with the Hanoi recension, which can be considered the earliest extant version. The mural opens with King Miaozhuang discussing his daughters’ marriages with court officials, a scene that closely parallels the opening of the Hanoi recension. The text states: “At that time King Miaozhuang harbored sorrow in his heart and was troubled by a single thought. He summoned his civil and military officials and said to them: ‘I am now advanced in age, yet I have no sons. I have only three daughters. I wish to consult with you: if each of them was married, how would it be?’” (DGXB, pp. 4b–5a). This is followed by the king’s formal announcement to his daughters, likewise reflected in the mural (DGXB, p. 6b). By contrast, the Hangzhou recension devotes considerable space to the miraculous circumstances of the births of three princesses, episodes that do not appear in the Xinjin mural (GPBJ, pp. 4a–7b).

Subsequent developments in the mural narrative likewise correspond closely to the Hanoi recension. Scenes depicting Miaoshan’s confinement in the rear garden, her sisters’ visit accompanied by their husbands, her retreat to the Convent of White Sparrows, the burning of the convent, her execution, descent into the underworld, resurrection, journey to Xiang Mountain, and the miraculous cure of King Miaozhuang all follow the general outline preserved in the Hanoi recension. Particularly noteworthy is the encounter with the green dragon in the wilderness, a detail specific to the Hanoi recension: “Princess Miaoshan suddenly saw a green dragon, dozens of

chi long,

22 breathing fire from its mouth. Terrified, she dared not move” (DGXB, p. 29b). This dragon is clearly depicted in the Xinjin mural.

At the same time, the mural also incorporates elements that are found only in the more elaborate Hangzhou recension and are absent from the Hanoi recension. These include scenes depicting King Miaozhuang personally visiting Miaoshan in the rear garden to persuade her to accept marriage (Scenes 5 and 6). The Hangzhou recension provides detailed poetic descriptions of this encounter, including Miaoshan’s firm rejection and her gesture urging the king to return to the palace (GPBJ, pp. 27b–29b). The mural’s visual representation of this exchange closely parallels these passages, despite their absence from the Hanoi recension. On the whole, the debate over Miaoshan’s refusal to marry occupies significantly more narrative space in the Hangzhou recension than in the Hanoi one, a feature also reflected in the Xinjin mural (Scenes 4–7).

Additional points of convergence with the Hangzhou recension include the ritualized circumstances of Miaoshan’s execution, particularly the construction of a decorated tower and the public recitation of the sacrificial text (

jiwen 祭文) for the still-living princess. The Hangzhou text describes these events in detail (GPBJ, pp. 53b–54a), and corresponding visual elements appear in the mural (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). The participation of celestial emissaries and the earth god (tudi) in Miaoshan’s journey to Xiang Mountain also parallels details found only in the Hangzhou recension (GPBJ, p. 83a). Conversely, the Xinjin mural offers only a highly compressed depiction of the underworld, unlike either recension of the

Baojuan of Xiangshan, both of which describing Miaoshan’s tour of hells.

Taken together, these observations demonstrate that the pictorial narrative of the Miaoshan story at Guanyin Monastery in Xinjin does not correspond precisely to any surviving written version that can be securely dated to the fifteenth century. Instead, it combines key elements found separately in both the Hanoi and Hangzhou recensions, while omitting or modifying other episodes. As a result, the Xinjin mural must be regarded as a unique Ming-dynasty visual interpretation of the Miaoshan narrative. Although closely related to the vernacular baojuan traditions, it preserves an independent pictorial version of the story that is not exactly reflected in later textual sources that we possess now.

4. Multiple Pictorial and Written Versions of the Miaoshan Story

The discrepancies between the Xinjin mural and the two early recensions of the Baojuan of Xiangshan raise broader questions concerning the diversity of Miaoshan narratives during the Ming dynasty. Several explanations may be proposed.

First, it is likely that multiple recensions of the Baojuan of Xiangshan circulated at the time the Xinjin mural was painted. The narrative reflected in the mural appears to differ from the version preserved in the Hanoi reprint of 1772 while sharing certain features with the Hangzhou recension of 1773. It is therefore possible that a local Sichuanese written version of the Miaoshan story existed in the fifteenth century but has not survived.

Second, oral variants of the Miaoshan story may have circulated alongside written

baojuan texts in fifteenth-century Sichuan. During the Ming dynasty, the Miaoshan narrative existed in multiple literary forms, including prose hagiographies and dramas, several of which survived only in late sixteenth- or early seventeenth-century printed editions (

Dudbridge 2004, pp. 57–67, 73–79;

Yü 2001, pp. 439–41;

Sun 2017, pp. 45–106). Although often based on the

Baojuan of Xiangshan, these vernacular texts incorporate significant variations. The Xinjin mural may thus reflect an alternative narrative tradition that was transmitted orally or through now-lost written texts, while remaining broadly aligned with the

baojuan tradition.

Third, it is important to recognize that pictorial representations of religious narratives in pre-modern China do not necessarily correspond exactly to any single textual source (

Katz 1999).

23 Rather than seeking a one-to-one relationship between image and text, the Xinjin mural should be understood as an autonomous work of art that draws selectively on written narratives, oral traditions, and local religious knowledge. The preferences of the artists and patrons who commissioned the mural must also be taken into account.

One also needs to regard the Xinjin mural of Xiangshan in the context of other pictorial versions of the Ming dynasty. If we turn to the visual versions of the Miaoshan story, created in various materials in the fifteenth—sixteenth centuries, we can find considerable difference in terms of contents. Perhaps the earliest surviving pictorial representations of this narrative are the painted clay bas-reliefs (

bisu 壁塑) in the Hall of Great Mercy (Dabeidian 大悲殿) of the Monastery of Repaying the Mercies (Baoensi 報恩寺) in Pingwu 平武 County, Sichuan, constructed between 1440 and 1460 under imperial sanction by local

tusi 土司 chieftains. Three walls of the Hall of Great Mercy are occupied by reliefs depicting the Miaoshan story (measuring 3.2 m in length, 2.85 m in width, and with a total area of 91.2 square meters) arranged around a monumental statue of Thousand-armed Guanyin (

Xiang 1991;

Liu and Yang 2014, pp. 79–102). While compositionally similar to the Xinjin mural, illustrations of the Miaoshan story in Pingwu are performed in another material and thus differ from the wall paintings. Still, the contents are obviously derived from the popular version of the Miaoshan narrative, presumably also the

Baojuan of Xiangshan.

24 At the same time we can observe certain difference from the Xinjin mural of Xiangshan: for example, the reliefs from Pingwu devote much more space to the Miaoshan’s tour of hells,

25 which in Xinjin is represented only by her meeting with King Yama. Still, these reliefs also testify to the spread of the Miaoshan subject in the Sichuan area in the Ming dynasty.

26A later pictorial cycle of Miaoshan appears in the murals of the Hall of Great Compassion (Dabeidian 大悲殿) at the Monastery of Great Wisdom (Dahuisi 大慧寺) in Beijing, constructed around 1513 by the palace eunuch Zhang Xiong 张雄 (

Z. Wang and Shan 1994, p. 134;

M. Wang 2007, pp. 13–15). These magnificent murals are located on the both sides of the large statue of Thousand-armed Guanyin (original bronze statue of the tenth century was later substituted by the clay one) and occupy 247.64 square meters in total. Therefore, the composition of murals is similar to the previous two cases. The Dahui murals follow the storyline of the

Baojuan of Xiangshan, particularly the version represented by the Hanoi recension (

Berezkin 2017a, pp. 20–39). However, comparison with the Xinjin mural reveals substantial differences, such as inclusion of extensive underworld scenes and additional episodes absent from the Xinjin cycle (such as the scenes of the nuns meeting Miaoshan in the Convent of White Sparrows as well as King Miaozhuang printing scriptures) (

Z. Wang and Shan 1994, pp. 118–19).

These examples illustrate the considerable diversity of Miaoshan narratives in visual form during the Ming dynasty. While all of these pictorial cycles demonstrate a clear relationship to popular tradition of baojuan narratives, they also exhibit a high degree of independence from specific textual sources (that survived as later printed copies). The Xinjin mural, in particular, stands out as an early and distinctive visual articulation of the Miaoshan story within Sichuan’s local Buddhist culture. The search for sources of imagery in the Xinjin mural of Xiangshan can constitute the topic of further research.