The Bible Rearranged—How the Rites of the 1979 American Book of Common Prayer Use the Bible as a Source

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

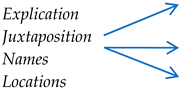

2.1. The Four General Categories

2.2. Suggestion

This is a representative example of Cranmer’s rhetorical brilliance and skill as a translator. As Jacobs (2019, p. 63) explains,Almighty God, give us grace that we may cast away the works of darkness, and put upon us the armor of light, now in the time of this mortal life in which thy Son Jesus Christ came to visit us in great humility; that in the last day, when he shall come again in his glorious majesty to judge both the quick and the dead, we may rise to the life immortal.

It was C. S. Lewis’s belief that the virtuosity [of Cranmer’s prose] arises from the need to adapt Latin devotional language to the very different character of English: Latin translated over-literally tends to be precious and pompous, and Cranmer was determined to avoid these traps. The Latin originals were [to quote Lewis] ‘almost over-ripe in their artistry’; the English of the BCP ‘arrests them, binds them in strong syllables, strengthens them even by limitations, as they in return erect and transfigure it. Out of that conflict the perfection springs.

2.3. Allusion

2.4. Quotation

Besides this you know what hour it is, how it is full time now for you to wake from sleep. For salvation is nearer to us now than when we first believed; the night is far gone, the day is at hand. Let us then cast off the works of darkness and put on the armor of light; let us conduct ourselves becomingly as in the day, not in reveling and drunkenness, not in debauchery and licentiousness, not in quarreling and jealousy. But put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh, to gratify its desires.(Rom. 13.11-14)

O God, whose blessed Son was manifested that he might destroy the works of the devil and make us the children of God and heirs of eternal life: Grant us, we beseech thee, that, having this hope, we may purify ourselves even as he is pure; that, when he shall appear again with power and great glory, we may be made like unto him in his eternal and glorious kingdom.

2.5. Appropriation

Here, a large portion of text is made into a liturgical unit.I will wash my hands in innocence, O Lord, *that I may go in procession round your altar,Singing aloud a song of thanksgiving *and recounting all your wonderful deeds

| O Lord, shew thy mercy upon us. | |

| Answer. | And grant us thy salvation. [Ps. 85.7] |

| Priest. | O Lord, save the Queen. |

| Answer. | And mercifully hear us when we call upon thee. |

| [adapted from Ps. 20.923] | |

| Priest. | Endue thy Ministers with righteousness. |

| Answer. | And make thy chosen people joyful. [Ps. 132.9] |

| Priest. | O Lord, save thy people. |

| Answer. | And bless thine inheritance. [Ps. 28.11] |

| Priest. | Give peace in our time, O Lord. |

| Answer. | Because there is none other that fighteth for us, |

| … | but only thou, O God. [Ps. 122.7] |

| Priest. | O God, make clean our hearts within us. |

| Answer. | And take not thy Holy Spirit from us. [Ps. 51.11a and 12b] |

| Celebrant | There is one Body and one Spirit; |

| People | There is one hope in God’s call to us; |

| Celebrant | One Lord, one Faith, one Baptism; |

| People | One God and Father of all. (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 299). |

2.6. The Five Possible Sub-Categories

2.6.1. Subcategory 1: Therefore

The main request is for the Father to make the offering acceptable so that it would become Christ’s Body and Blood, and the institution narrative functions to clarify who this Jesus is. Cranmer places the narrative in the same grammatical situation in 1549:O God, we beseech you to make in every respect blessed, approved, ratified, spiritual (reasonable) and acceptable, so that it may become for us the Body and Blood of your most beloved Son, Jesus Christ our Lord, who, on the day before he suffered, took bread in his holy and venerable hands.

Even Rite I, Prayer I retains this by introducing the narrative with the word “for,” used not as a proposition, but in its older, and now much less common usage, as a conjunction: “…and in his holy Gospel command us to continue, a perpetual memory of that his precious death and sacrifice, until his coming again. For in the night in which he was betrayed, he took bread…” (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 334). The point is that in the institution narrative, a biblical text is being quoted (or we should say more accurately, paraphrased) in order to provide the warrant for the current action. We are doing this because, on the night Jesus was betrayed, he took bread. Therefore uses of Scripture assume a Scriptural institution. Some modern eucharistic prayers express the “therefore” that often follows the institution narrative (the Unde et memores in the Roman Canon) in ways which disguise this, such as “And so, Father, calling to mind…” in Prayer B of Common Worship (Church of England 2000, p. 190) or “We now obey your Son’s command” in Eucharistic Prayer I of the Scottish Liturgy (Scottish Episcopal Church 2022, p. 9).Heare us (o merciful father) we besech thee: and with thy holy spirite and worde, vouchsafe to blesse and sanctifie these thy gyftes, and creatures of bread and wyne, that they maie be unto us the bodye and bloude of thy moste derely beloved sonne Jesus Christe. Who in the same nyght that he was betrayed: tooke breade….

2.6.2. Subcategory 2: Pattern

The causal connection between the acceptance of the ancient sacrifices and the request that God favor and accept the sacrifice of those making an offering in the present is indicated by the adverb sicuti (just as). The appeal is not primarily to the act of offering undertaken by Abel, Abraham, and Melchizedech. Rather, the appeal is to God’s acceptance of those sacrifices. One of the most noteworthy aspects of this example is that the appeal is not to one or two particular passages, but to a whole collection of them, both the set of passages in Genesis that describe each of these sacrifices plus the mention of these events throughout the New Testament, especially in Hebrews. This example from the Roman Canon highlights a connection that is often seen between Pattern uses of Scripture and a characteristic I call “Explication,” which I discuss near the end.Upon these sacrifices, be pleased to look with a favorable and kindly countenance, and to accept them as you were pleased to accept the dutiful offerings of your righteous servant Abel, and the sacrifice of our patriarch Abraham, and that which your high priest Melchizedek offered to you, a holy sacrifice, a spotless sacrificial offering.

2.6.3. Subcategory 3: Imitation

2.6.4. Subcategory 4: Composite

Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world:have mercy on us.Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world:have mercy on us.Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world:grant us peace.

2.6.5. Subcategory 5: Amended

| Rom. 15.13, RSV | 1979 BCP (pp. 60, 73, 102, 126) |

| May the God of hope fill you with all joy and peace in believing, so that by the power of the Holy Spirit you may abound in hope. | May the God of hope fill us with all joy and peace in believing through the power of the Holy Spirit |

| Eph. 3.20-21, RSV | 1979 BCP (pp. 60, 73, 102, 126) |

| Now to him who by the power at work within us is able to do far more abundantly than all that we ask or think, to him be glory in the church and in Christ Jesus to all generations, for ever and ever. Amen. | Glory to God whose power, working in us, can do infinitely more than we can ask or imagine: Glory to him from generation to generation in the Church, and in Christ Jesus for ever and ever. Amen. |

2.6.6. Three Possible Characteristics

Characteristic 1: Explication

I do not want you to be unaware, brothers and sisters, that our ancestors were all under the cloud, and all passed through the sea, and all were baptized into Moses in the cloud and in the sea, and all ate the same spiritual food, and all drank the same spiritual drink. For they drank from the spiritual rock that followed them, and the rock was Christ.(1 Cor. 10.1-4)

The choice to appeal to those sacrifices indicates a typological exegesis of each as a type or figure of the Christian sacrifice.…clearly chosen because Christian liturgists saw the Eucharist as the fulfilment, not of the Temple sacrifices, of the Old Covenant… but earlier offerings recorded in the Old Testament. These offerings were not offerings repeatedly offered, as were the Levitical offerings, by a succession of priests who were dying and constantly being replaced, but were in each case the offerings of one man, who had no successors.

Characteristic 2: Names and Locations

Characteristic 3: Juxtaposition

3. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “Glorious majesty” is also found in the translations of Ps. 145.5 and 12 in the 1611 King James Bible, though not in its predecessor, the Great Bible of 1539, which is the source of the so-called Coverdale psalter that was included in every BCP until the 1979 American book. One has to wonder if the use and ubiquity of the phrase in the BCP influenced (whether consciously or unconsciously) the introduction of the phrase into those two verses in 1611. Also noteworthy is the fact that Ps. 90 is introduced into the 1662 BCP as one of the two psalms that is to be used as the body is born into the church in the Burial of the Dead, possibly because of the affection for this phraseology that the 1549 BCP and its successors instilled in its users. See Cummings (2013, p. 451). |

| 2 | My thanks to one of the anonymous reviewers of the article, who suggested much from this paragraph. See also (Mohrmann 1957; 1961–1977, pp. 87, 103, 143). |

| 3 | At the end of the Te Deum in Matins (Cummings 2013, BCP, p. 9); in the first exhortation in the 1549 BCP (Cummings 2013, p. 23); in the Prayer of Humble Access (Cummings 2013, p. 34); in the first petition of the Litany (Cummings 2013, p. 41); in the exorcism in the first baptismal rite of 1549, but which disappears in all subsequent books (Cummings 2013, p. 48); and in the anthem, “O Saveour of the world save us, which by thy crosse and precious bloud hast redeemed us…” in the Visitation of the Sick (Cummings 2013, p. 77). In the 1979 BCP, it remains at the end of the Rite I Te Deum (p. 53) and the Litany (p. 148), and also in an anthem provided for in the new liturgy for Good Friday (p. 282) and the Ministration to the Sick (p. 455). |

| 4 | Near the end of the eucharistic prayer (“humbly besechyng thee, that whosoever shalbee partakers of thys holy Communion, maye worthely receive the most precious body and bloude of thy sonne Jesus Christe”; Cummings 2013, p. 31) and then again in the postcommunion prayer (“that thou hast vouchsafed to feede us in these holy Misteries, with the spirituall foode of the moste precious body and bloud of thy sonne, our saviour Jesus Christ”; Cummings 2013, p. 36). |

| 5 | The text of the Great Bible (1539) is taken from http://textusreceptusbibles.com/. Accessed 19 August 2018. Subsequent quotations from it will be identified with the abbreviation GB. |

| 6 | Many other examples could be listed: see the way in which Christ’s blood is discussed in Eph. 1.17; 2.13, Col. 1.14; 20; 1 Pet. 1.2; 1 Jn. 1.7; 5.6, 8; Rev. 1.5; 7.14; 12.11; and 19.13. |

| 7 | When I cite biblical passages in relation to the 1979 BCP, I do so in reference to the Revised Standard Version, since that is what the compilers were using (the NRSV was not published until 1989); see (Hatchett 1980, pp. 34–35, 591). The only exception are the psalms; chapter and verse divisions always refer to the psalter in the 1979 BCP. |

| 8 | Because this taxonomy was proposed in an earlier article, it seemed more confusing if I changed the term in this article. Nonetheless, I have come to think that “Paraphrase” is probably a better term than “Allusion.” While an Allusion that is not recognized by a reader has “failed,” a paraphrase can succeed even if the use if not identified by the reader. |

| 9 | The question that most closely conforms to this in the 1928 American BCP is this: “Wilt thou take heed that this Child, so soon as sufficiently instructed, be brought to the Bishop to be confirmed by him?”; (The Book of Common Prayer 1928, p. 277). |

| 10 | The gendered language of “manhood” is not used here or elsewhere in the 1979 BCP, though it is found in the older English and American BCPs. Most famously, it is used in the prayer that accompanies the signing with the cross just after the water bath in baptism: “We receive this Child (Person) into the congregation of Christ’s flock; and do sign him with the sign of the Cross, in token that hereafter he shall not be ashamed to confess the faith of Christ crucified, and manfully to fight under his banner, against sin, the world, and the devil”; (Cummings 2013, p. 145 (in the 1559 BCP) and p. 412 (in the 1662 BCP)); see also (The Book of Common Prayer 1928, p. 280). |

| 11 | “At least two of the following Lessons are read, of which one is always the Lesson from Exodus”; (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 288). |

| 12 | For a fuller engagement with the theology of marriage in the English and American BCPs, see (Olver 2015). |

| 13 | One theory about the origin of the phrase picks up that the direction in 1 Tim. 3:9 concerns deacons. Jungmann notes that Brinktrine theorized that because “the passage at times was understood in a Eucharistic sense, and the naming of the deacons, to whom the chalice pertained, could have led to this chalice formula” (Jungmann 1951, II:200 n. 38; Brinktrine 1930, pp. 493–500). |

| 14 | Interestingly, all of the memorial acclamations in the 1979 BCP are in the form of a declaration (“Christ has died. Christ is risen. Christ will come again”), while the acclamations in the current Roman Missal are addressed to Christ. |

| 15 | See (Blunt 1866, p. 263). One reason for this was that, as Blunt notes, “the ancient English use was to reckon one Sunday with the Octave of Epiphany, and five Sundays after the octave.” He goes on to explain that “it is strikingly adapted for transfer to the end of the Trinity season (if required), according to the anciently received practice of our own and other branches of the Western Church”; (Blunt 1866, p. 264). The 1979 BCP reflects this and appoints it for Proper 27, followed by Cranmer’s “all holy Scriptures to be written for our learning” collect as Proper 28, and finally “Christ the King” as Proper 29. |

| 16 | The opening rubric of the rite reads in part: “It is desirable that this take place at a Sunday service. In the Eucharist it may follow the Prayers of the People preceding the Offertory. At Morning or Evening Prayer it may take place before the close of the Office”; (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 439). |

| 17 | Further, the ‘Thanksgiving for a Child’ appoints the Magnificat, Ps. 116, or Ps. 23 as an Act of Thanksgiving; (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, pp. 441–43). |

| 18 | For the use of the Benedicite at the end of the Mass, see (Jungmann 1951, pp. I:294, II:460–64). For a discussion of the relationship between the three Lukan canticles that are fixed in the divine office, see (Lohfink 2003, pp. 136–50). |

| 19 | See the discussion of this in (Jungmann 1951, p. I:290–98). |

| 20 | Jungmann discusses the origin of this in the Frankish era in (Jungmann 1951, pp. II:80–81). |

| 21 | An unfortunate change in the 1979 revisions of the Offices is that while “Lord, open thou our lips” properly drops out the beginning of Evensong, “O God make speed to save us” disappears from Morning Prayer. This latter versicle was said at the opening of all the offices in the West for at least 1400 years, which makes its absence perplexing. |

| 22 | ‘Te Deum’ in (Cross and Livingstone 2005, pp. 1581–82; Hatchett 1980, pp. 123–24; Blunt 1866, pp. 198–200). The psalm verses used in the suffrages at the conclusion of the Te Deum are Pss. 2.11; 145.2 123.4; 33.22; 31.1; 71.1. The psalm verses used in the English BCP suffrages are Pss. 85.7; 20.9; 132.9; 28.11; 122.7 (as modified in the primer of Henry VIII); and 51.11a and 12b (taken from Hatchett 1980, p. 124). |

| 23 | The translation in the Coverdale Psalter, which were used in all English and American BCPs until the 1979 American BCP, translates the verse this way: “Save, Lord and hear us, O King of heaven: when we call upon thee,” though the Coverdale version accurately translates the Vulgate version. |

| 24 | Their presence in the American BCPs is rather odd, as Hatchett explains: “The American revision in 1789 retained only the first and the last sets” of the suffrages from the English BCP. “In the 1892 Book the full set was restored to Evening Prayer with two changes: “state” was substituted for “king” and “For it is thou, Lord, only, that makest us dwell in safety” for “Because there is none other that fighteth for us, but only thou, O God” (Hatchett 1980, p. 124). |

| 25 | Hatchett points out that these suffrages were also added sometimes to the Gloria in excelsis (Hatchett 1980, p. 118). |

| 26 | A few common examples are exceptions to this pattern and are not direct Appropriations: “The Lord be with you/and with your spirit”; “Let us bless the Lord/Thanks be to God,” are probably the two most of common of these. |

| 27 | For a discussion of the origin of the penitential sentences that were introduced at the beginning of Morning Prayer in the 1552 English BCP (most of which were taken from the Capitula, where they were used in Lent and for which there was precedence in Matins in the Sarum breviary), see (Blunt 1866, p. 181). |

| 28 | “The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God, and the communion of the Holy Spirit be with all of you” Hänggi and Pahl 1968, p. 405 (Addai and Mari) and pp. 244–45 (St James). |

| 29 | This verse is picked up several times elsewhere in the Old Testament: Job 34.15; Ps. 104.29; Eccl. 12.7; Sir. 41.10; 1 Mac. 2.63. |

| 30 | Paul Bradshaw suggests as much in (Bradshaw 2002, p. 219). |

| 31 | Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults (Catholic Church et al. 1988, p. 134). E.C. Whitaker’s collection of ancient baptismal texts (Whitaker 1970) contains several examples: in the Armenian rites prayer of blessing over the baptismal waters, a number of divine actions are appealed to as a basis for the present action, including “thou didst send thy holy apostles, laying on them the command to preach and baptize in the Name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost all the nations” [Mt. 28.19] (p. 63); the Ambrosian Manual (whose manuscript is from the tenth century) has a similar reference in the exorcism prayer over the water that precedes the blessing of the water: “who said to his disciples, ‘Go, teach all nations, baptizing them in the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost’” [Mt. 28.19] (p. 139); the Western Sarum rite from England cites the Mt. 28.19 passage as a basis for the blessing of the water (pp. 243–44). The current BCP in the Episcopal Church uses the word “Therefore” to introduce the citation: “Therefore in joyful obedience to your Son, we bring into this fellowship those who come to him in faith, baptizing them in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit”; (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, pp. 306–7). |

| 32 | There was a significant shift in some circles in the second part of the twentieth century to discourages the claim that additional gifts of the Spirit are conferred at Confirmation. The 1979 BCP leans strongly in this direction, particularly with the note at the beginning of the baptismal rite, “Holy Baptism is full initiation by water and the Holy Spirit into Christ’s Body the Church” (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 298) and the fact that the prayer for the seven-fold gifts of the Spirit was edited in such a way as to remove the mention of those gifts. |

| 33 | The third collect for the Nativity in the current Roman Missal (“At the Mass during the day”); (The Roman Missal 2011, p. 175); it is the Collect for the Second Sunday after Christmas in (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 162). Hatchett notes that this collect is appointed for the first Mass of Christmas in the Veronensis Sacramentary (no. 1239), as a Christmas collect for Matins or Vespers in the Gelasian Sacramentary (no. 27), and in “other prayers for the birthday of Our Lord” in the Gregorian Sacramentary (no. 52); see (Hatchett 1980, p. 170). |

| 34 | Baumstark points to both specific examples, along with accompanying scholarly investigation, in (Baumstark 1958, pp. 72–73). |

| 35 | These sacrifices are important to Daniélou’s approach in the chapter on the Eucharist in (Daniélou 1956). However, his interpretation of them is not based on a close reading of the text of the Roman Canon itself: “The Eucharist is the memorial of the sacrifice of Abel, Melchisedech, and Abraham,” he writes (p. 143). But, a careful reading of the Supra quae makes it clear that those sacrifices are not called figures or types of the Eucharist. Rather, they are examples of sacrifices which God accepted and which must have been pleasing. In particular, the Supra quae prays in a way as to rely or lean on God’s past acceptance as a basis to now ask in faith that God would accept this particular sacrifice, the offered bread and wine. There are examples in the Latin sacramentaries, however, of prefaces that describes these three sacrifices as “figures” (figurum) of Christ (see Gelasian Sacramentary, no. 20; Mozarabic Sacramentary, no. 1420; Veronensis Sacramentary, no. 1250. The Gelasian and Veronensis both state that Christ disclosed these in his birth (hodie natus Christus implevit) while the Mozarabic version says simply that Christ, our great high priest, disclosed that to which the figures pointed. In the 1962 Misalle Romanum, there are no prefaces that mention Melchizedech, though his name appears in many Alleluias in the propers for priest and bishop confessors or martyrs, as well as in the votive Mass for Christ, the Great High Priest, and in the prayer for the blessing of a chalice. |

| 36 | “The following days are observed by special acts of discipline and self-denial: Ash Wednesday and the other weekdays of Lent and of Holy Week, except the feast of the Annunciation” (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 17). |

| 37 | “When observed, the ceremony of the washing of feet appropriately follows the Gospel and homily” (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 274). For more direction, see (The Book of Occasional Services 2003, p. 93). |

| 38 | There are a great many acclamations in the Gospels where persons ask Jesus to have mercy upon them: Mt. 9.27; 15.22; 17.15; 20.30, 31; Mk. 10.47, 48; Lk. 17.31; 18.38, 39. |

| 39 | The Book of Common Prayer (1979, pp. 44–45, 82); see (Hatchett 1980, p. 104). Note that in Rite II, Ps. 95.7b is restored, but placed after verses 9 and 13 from Ps. 96. Also, for the first time in any of the American books, the entirety of Ps. 95 (in the Coverdale translation) is supplied for use (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, pp. 45,146). |

| 40 | Bradshaw (2002), ‘Chants of the Proper of the Mass,’ pp. 104–5. The sequences, which were suppressed in the conciliar reforms, were always compositions and were never simple appropriations from the Psalms or other portions of Scripture; see (Sartore et al. 1992, p. II:558). |

| 41 | The Book of Common Prayer (1979, p. 131. The same passage is given as the Reading in the Daily Devotions ‘At the Close of the Day’; p. 140. |

| 42 | Cummings (2013, p. 455). Hatchett provides a bit more history: “In the Sarum rite it was a daily antiphon to the Nunc dimittis during the third and fourth weeks of Lent. The anthem was popular in Germany, and Luther’s metrical translation of it was used in the burial rites in German church orders. The last line of Cranmer’s version, ‘Suffer us not at our last hour for any pains of death to fall form thee,’ was inspired by Luther’s metrical paraphrase of it or by Coverdale’s English translation of it” (Hatchett 1980, p. 485). It seems that it became a popular song sung during battle and was also sung at Saturday Compline. The use in battle seems almost to have been understood as an incantation or verbal talisman, which may be why the Synod of Cologne (1316) directed that it could only be used with the permission of the bishop (Bell 1853, p. 178). |

| 43 | “Christ our Pascall lambe is offred up for us, once for al, when he bare our sinnes on hys body upon the crosse, for he is the very lambe of God, that taketh away the sines of the worlde: wherfore let us kepe a joyfull and holy feast with the Lorde” (Cummings 2013, p. 32). |

| 44 | While it is true that the passive perfect construction was starting to have the force of a present-tense verb in Late Latin, Cranmer keeps the past sense of the Aorist in 1549, and it seems unlikely that the framers of the 1979 American book were looking to Late Latin to inform their choices. |

| 45 | This points to an important issue that arises in the attempt to discern the uses of Scripture within a liturgical text, namely, what manuscript or translation is being used by the composer/redactor of the liturgy? In the minds of the committee responsible, they may not understand either of these Appropriations to be “Amended” at all, if they undertook their own translation of the Greek. But the English speaker who studies the text is likely to be left with the impression that the compilers of the rite have taken some liberties with the text, since the 1979 BCP typically uses the RSV (see the earlier note on this, as well as examples of Appropriations that are taken directly from the RSV: see The Book of Common Prayer 1979, pp. 105–6, 109–10). I discuss the matter of which Biblical text is the source for a rite in my earlier article, as this becomes quite complicated with Latin texts that were composed before Jerome’s Vulgate and the wide variety in the Vetus Latina, and also for Greek rites, given the variants in biblical manuscripts. |

| 46 | The Book of Common Prayer (1979, p. 154). In the Preface to the 1549 BCP, Cranmer includes responsory (“Responds”) in his list of things which have obscured the previous clarity of the Church’s liturgy: “ But these many years passed, this godly and decent order of the ancient fathers hath been so altered, broken, and neglected, by planting in uncertain stories, Legends, Responds, Verses, vain repetitions, Commemorations, and Synodals…” (Cummings 2013, p. 866). This responsory remains in all the subsequent English and American BCPs. |

| 47 | Note that neither the version in all the previous English and American books, nor the version in the 1979 BCP, follow exactly the pattern described above by Harper. If it did, the second time Ps. 44.26 is used, only the first or second half of the verse would be use, and only the first part of the Gloria Patri. Further, it is only in the 1979 version that the refrain is used to conclude the responsory; in all the previous Books, the rite continued with the versicles and responses. |

| 48 | The term “antiphon” was used in the Latin tradition not only for what are commonly considered antiphons, the proper texts appointed to be said before and after the appointed psalms and canticles in the Divine Office, but also for the introit. The texts of these were taken primarily from the psalms but also at times from the gospel reading for the day. “Some of the most important antiphons are those that were sung at the Benedictus in the morning office and the Magnificat in the evening office, some taking their text from the gospel reading of the day. Some Latin antiphons are sung as independent chants, as a devotional ‘anthem’ at the end of the office or as part of the repertory of chants sung during a liturgical procession”; (Bradshaw 2002, ‘Antiphon’, p. 17). |

| 49 | The debate between them about which term is more appropriate does not affect my argument here. For a summary of de Lubac’s approach, with some reference to his differences with Daniélou, see (Wood 1998, pp. 25–51). For an introduction to Daniélou’s approach, specifically as it concerns sacraments, see (Daniélou 1956, pp. 3–17). The wide variety of uses of and meanings applied to the terms “typology” and “allegory” in the twentieth century is laid out in (Martens 2008, pp. 283–317). |

| 50 | In an essay adapted from his series introduction to The Church’s Bible, Robert Louis Wilken argues that the identification of this passage as a hermeneutical key for a Christian reading of the Old Testament begins with Origen, who maintained that Christian interpreters should follow Paul’s method and “should apply this rule in a similar way to other passages.” Augustine agreed: Paul’s reading of the rock in the wilderness “is a key as to how the rest [of the Old Testament] is to be interpreted”; see (Wilken 2008, pp. 25–27). He also, it is worth pointing out, uses allegory to identify the approach what Goppelt calls typology. Matthew Bates demonstrate how early Christian interpreted the Old Testament in Trinitarian theology; see (Bates 2016). |

| 51 | Daniélou and de Lubac rely heavily on Origen, who, along with Jerome, spoke of three senses: historical, moral, and mystical. Augustine and Cassian, however, use a quadripartite delineation: literal, tropological (moral), allegorical (which corresponds to the mystical in the tripartite scheme), and anagogical (applying the Scriptures eschatologically). See the clarifying discussion from (Wood 1998, pp. 27–30). For Daniélou’s argument that the four-fold distinction is simply a development of a more basic distinction between literal and spiritual, see (Daniélou 1948, pp. 119–26). |

| 52 | Buchanan (1984, p. 7). We must also keep in mind that the New Testament does not use of the term “Eucharist.” Vasey, however, is not being anachronistic, but merely intends to point out that none of the institution narratives nor the discussion of the Lord’s Supper in 1 Corinthians specifically describes this action as a sacrifice, though cultic language is used in 1 Corinthians 10 in the discussion of the altar and pagan sacrifices. |

| 53 | For a rich discussion of these examples and the developing concept of sacrifice amongst Greeks, Jews, and Christians in this period, see (McGowan 2012, pp. 1–45). |

| 54 | Fenwick (1986, p. 11). Massey Shepherd notes the similarities between a sermon of Eusebius that dates from c. 314-19 and is appended to Book X of Eusebius’s Ecclesiastical History. One of those parallels is in X.70 where Eusebius refers to “the region above the heavens, with the models of earthly things which are there, and the so-called Jerusalem above, and the heavenly Mount of Zion.” See (Shepherd 1963, pp. 109–13). |

| 55 | My thanks to Timothy Brunk at the 2017 NAAL meeting of the Liturgical Theology Seminar for suggesting that Gordon Lathrop’s category is so fundamental to the very nature of liturgy as to warrant as place in my taxonomy. Gordon Lathrop’s liturgical theology, Holy Things, is organized around the broad theme of juxtaposition: (Lathrop 1993). See also (Gerhards and Kranemann 2017, pp. 262–66; Deeg 2004, pp. 34–52; Radner 2016, pp. 205–34). |

| 56 | (De Zan 1997, p. 331, n. 1). He continues: “…we should rightly distinguish a biblical or patristic passage in its original setting (the Bible or the writings of the Fathers) from a passage that forms part of a ritual program with its own shape and functions. In the first case we should speak of biblical or patristic texts; in the second, we should speak of biblical-liturgical or patristic-liturgical texts.” For more on how the context of the liturgical reading of Scripture alters the text, see (De Zan 1997, pp. 32–51 (42–50); Irwin 1994, pp. 83–127). |

| 57 | The psalm is appointed as the Gradual in the 1979 American BCP; (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 895 (Year A), p. 906 (Year B), p. 917 (Year C)). The psalm translation is from (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, p. 650). |

References

- Bates, Matthew W. 2016. The Birth of the Trinity: Jesus, God, and Spirit in New Testament and Early Christian Interpretations of the Old Testament, reprint ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baumstark, Anton. 1958. Comparative Liturgy. Translated by Frank Leslie Cross. London: A. R. Mowbray. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, George, ed. 1853. Notes and Queries. vol. 8, London. [Google Scholar]

- Blunt, John Henry. 1866. The Annotated Book of Common Prayer: Being an Historical, Ritual, and Theological Commentary on the Devotional System of the Church of England. London: Rivingtons. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, Paul F. 1992. The Use of the Bible in Liturgy: Some Historical Perspectives. Studia Liturgica 22: 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, Paul F., ed. 2002. The New Westminster Dictionary of Liturgy and Worship. Louisville: Westminster John Knox. [Google Scholar]

- Brinktrine, Johannes. 1930. Mysterium Fidei. Ephemerides Liturgicae 44: 493–500. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, Colin O., ed. 1984. Essays on Eucharistic Sacrifice in the Early Church. Grove Liturgical Study 40. Cambridge: Grove Books. [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth, Hezekiah. 1881. Young Folks’ History of Boston. Pittsburgh: Lorthrop. [Google Scholar]

- Catholic Church, United States Catholic Conference, and International Committee on English in the Liturgy. 1988. Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults, study ed. Washington: Publication/Office of Publishing and Promotion Services, United States Catholic Conference, no. 214-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvet, Louis Marie. 1992. What Makes the Liturgy Biblical?—Texts. Studia Liturgica 22: 121–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church of England. 2000. Common Worship: Services and Prayers for the Church of England. London: Church House Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, Frank Leslie, and Elizabeth A. Livingstone, eds. 2005. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 3rd rev. ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cuming, G. J. 1983. The Godly Order: Texts and Studies Relating to the Book of Common Prayer. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, Brian, ed. 2013. The Book of Common Prayer: The Texts of 1549, 1559, and 1662, reprint ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daniélou, Jean. 1948. Les divers sens de l’écriture dans la tradition chrétienne primitive. In Analecta Lovaniensia Biblica et Orientalia. Paris: Desclée de Brouwer. [Google Scholar]

- Daniélou, Jean. 1956. The Bible and the Liturgy. University of Notre Dame Liturgical Studies, v. 3. Chambersburg: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Alexander. 2004. Gottesdienst in Israels Gegenwart: Liturgie als intertextuelles Phänomen. Liturgisches Jahrbuch 54: 34–52. [Google Scholar]

- De Zan, Renato. 1997. Liturgical Textual Criticism. In Introduction to the Liturgy. Edited by Anscar J. Chupungco. Translated by Edward Hagman. I. Handbook for Liturgical Studies. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick, John R. K. 1986. Fourth Century Anaphoral Construction Techniques. Grove Liturgical Study 45. Cambridge: Grove Books. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, David Noel, ed. 1992. Anchor Bible Dictionary. 6 vols. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhards, Albert, and Benedikt Kranemann. 2017. Introduction to the Study of Liturgy. Translated by Linda M. Maloney. Pueblo Books. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Donald. 2007. Cranmer and the Collects. In The Oxford Handbook of English Literature and Theology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haller, Tobias Stanislas. 2015. The Episcopal Handbook, rev. ed. Edited by Barbara S. Wilson, Arlene Flancher and Susan T. Erdey. Harrisburg: Morehouse Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, John. 1991. The Forms and Orders of Western Liturgy from the Tenth to the Eighteenth Century: A Historical Introduction and Guide for Students and Musicians. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hatchett, Marion J. 1980. Commentary on the American Prayer Book. New York: Seabury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, Richard B. 1989. Echoes of Scripture in the Letters of Paul. Dunmore: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hänggi, Anton, and Irmgard Pahl, eds. 1968. Prex eucharistica: Textus e variis liturgiis antiquioribus selecti. Spicilegium Friburgense 12. London: Éditions Universitaires. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, Kevin W. 1994. Context and Text: Method in Liturgical Theology. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Alan. 2019. The Book of Common Prayer: A Biography. Lives of Great Religious Books. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jasper, Ronald C. D., and Geoffrey J. Cuming, eds. 1987. Prayers of the Eucharist: Early and Reformed, 3rd rev. ed. Pueblo Books. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jungmann, Josef A. 1951. The Mass of the Roman Rite: Its Origins and Development (Missarum Sollemnia). Translated by Francis A. Brunner. 2 vols. Glen Ellen: Benziger. [Google Scholar]

- Lathrop, Gordon. 1993. Holy Things: A Liturgical Theology. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lohfink, Norbert. 2003. The Old Testament and the Course of the Christian’s Day. The Songs in Luke’s Infancy Narrative. In In the Shadow of Your Wings: New Readings of Great Textsfrom the Bible. Translated by Linda M. Maloney. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, Peter. 2008. Revisiting the Allegory/Typology Distinction: The Case of Origen. Journal of Early Christian Studies 16: 283–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, Andrew B. 2012. Eucharist and Sacrifice: Cultic Tradition and Transformation in Early Christian Ritual Meals. In Mahl Und Religiöse Identität Im Frühen Christentum = Meals and Religious Identity in Early Christianity. Edited by Matthias Klinghardt and Hal Taussig. Texte Und Arbeiten Zum Neutestamentlichen Zeitalter 56. Manchester: Francke. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, Thomas. 1956. Praying the Psalms. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mohrmann, Christine. 1957. Liturgical Latin: Its Origin and Character. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mohrmann, Christine. 1961–1977. Études sur le latin des chrétiens. 4 vols. Storia e letteratura 65. Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, Bridget. 2010. The Collect in the Churches of the Reformation. London: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Olver, Matthew S. C. 2015. Contraception’s Authority: An Anglican’s Liturgical and Synodical Thought Experiment in Light of ARCUSA’s ‘Ecclesiology and Moral Discernment. Journal of Ecumenical Studies 50, no. 3: 417–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olver, Matthew S. C. 2019. A Classification of a Liturgy’s Use of Scripture: A Proposal. Studia Liturgica 49: 220–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olver, Matthew S. C. 2026. Collects. In The Oxford Handbook of the Book of Common Prayer. Edited by Paul F. Bradshaw, Luiz Carlos Teixeira Coelho and Ruth A. Meyers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Radner, Ephraim. 2016. Time and the Word: Figural Reading of the Christian Scriptures. Grand Rapids: Eerdmanns. [Google Scholar]

- Rituale Romanum Pauli V Pontif. 1834. Maximi jussu editum atqua a felicis Recordationis Benedicto XIV, auctum et castigatum. Venezia: Bassani. [Google Scholar]

- Sartore, Domenico, Achille M. Triacca, and Henri Delhougne, eds. 1992. Dictionnaire encyclopédique de la liturgie. vols. 1, A-L. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Episcopal Church. 2022. Scottish Liturgy 1982, Revised (2022), with Alternative Eucharistic Prayers. Available online: https://www.scotland.anglican.org/wp-content/uploads/Scottish-Liturgy-1982-revision-2022-with-covers.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Serra, Dominic E. 2003. The Roman Canon: The Theological Significance of Its Structure and Syntax. Ecclesia Orans 20: 99–128. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, Massey Hamilton. 1963. Eusebius and the Liturgy of St. James. Yearbook of Liturgical Studies 4: 109–25. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, Kenneth. 2004. The Lord’s Prayer: A Text in Tradition. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- The Book of Common Prayer. 1928. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- The Book of Common Prayer. 1979. New York: Seabury Press.

- The Book of Occasional Services. 2003. New York: Church Publishing.

- The Roman Missal: Renewed by Decree of The Most Holy Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, Promulgated by Authority of Pope Paul VI and Revised at the Direction of Pope John Paul II, 2011, 3rd typical ed. Collegeville: Liturgical Press.

- Whitaker, Edward C. 1970. Documents of the Baptismal Liturgy, 2nd ed. Alcuin Club Collections 42. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wilken, Robert Louis. 2008. How to Read the Bible. First Things 181: 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, Geoffrey G. 1978. Melchisedech, the Priest of the Most High God. The Downside Review 96: 267–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Susan K. 1998. Spiritual Exegesis and the Church in the Theology of Henri de Lubac. Grand Rapids: Eerdmanns. [Google Scholar]

| Appropriation | Quotation | Allusion | Suggestion |  |

| Therefore * Pattern ^ Imitation * Composite ^ Amended ⬪ | ||||

| 1549 BCP | Roman Canon |

|---|---|

| humbly besechyng thee, that whosoever shal bee partakers of thys holy Communion, maye worthely receive the most precious body and bloude of thy sonne Jesus Christe: and bee fulfilled with thy grace and heavenly benediccion, and made one bodye with thy sonne Jesu Christe, that he maye dwell in them, and they in hym. And although we be unworthy (through our manyfolde synnes) to offre unto thee any Sacryfice: Yet we beseche thee to accepte thys our bounden duetie and service, and commaunde these our prayers and supplicacions, by the Ministery of thy holy Angels, to be brought up into thy holy Tabernacle before the syght of thy dyvine majestie; (Cummings 2013, p. 31). | Upon these sacrifices, be pleased to look with a favorable and kindly countenance, and to accept them as you were pleased to accept the dutiful offerings of your righteous servant Abel, and the sacrifice of our patriarch Abraham, and that which your high priest Melchizedek offered to you, a holy sacrifice, a spotless sacrificial offering; We humbly pray you, almighty God, bid these [sacrifices] to be born by the hands of your [holy] angel to your lofty altar in the presence of your divine majesty, so that as often as we receive the most holy Body and Blood of your Son through this participation at the altar, we may be filled with all heavenly benediction and grace; (Hänggi and Pahl 1968, p. 434) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Olver, M.S.C. The Bible Rearranged—How the Rites of the 1979 American Book of Common Prayer Use the Bible as a Source. Religions 2026, 17, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel17010028

Olver MSC. The Bible Rearranged—How the Rites of the 1979 American Book of Common Prayer Use the Bible as a Source. Religions. 2026; 17(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel17010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlver, Matthew S. C. 2026. "The Bible Rearranged—How the Rites of the 1979 American Book of Common Prayer Use the Bible as a Source" Religions 17, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel17010028

APA StyleOlver, M. S. C. (2026). The Bible Rearranged—How the Rites of the 1979 American Book of Common Prayer Use the Bible as a Source. Religions, 17(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel17010028