1. Introduction

Since the 1990s, overseas China studies have sparked a new trend of on-the-spot investigation of Daoist rituals in mainland China. With the gradual deepening of field research, studies on local Daoism represented by folk Daoists have attracted attention, giving rise to a new research trend—step into local society and focused on the living Daoist tradition. A number of fieldwork research projects have all touched upon the Daoist rituals that exist within the territory of mainland China. Meanwhile, several sets of large-scale book series have been published successively.

1 Nevertheless, the geographical areas covered by these fieldworks are predominantly concentrated in the regions to the south of the Yangtze River.

2 As for the field research on Daoism in North China, it remains at an embryonic stage. In fact, we have rather limited knowledge regarding the Daoist priests in North China as well as their Daoist rituals.

Prior to Daoist studies, ethnomusicology turned to the research of Daoist rituals in North China in the early 1990s, exploring the Daoist music and ritual structures within them.

3 Among these, Stephen Jones’ research in recent years has endeavored to gain a comprehensive overview of the Daoist rituals in diverse backgrounds and regions across northern China. Based on his research, there exist a multitude of remarkable differences between the Daoist rituals in the northern regions and those in the southern regions (particularly in Fujian and Taiwan areas).

4 Thus, it becomes especially crucial to further augment the fieldwork cases regarding Daoist rituals in the northern regions (particularly those in rural areas), which serves as the fundamental precondition for carrying out more in-depth comparative studies between the north and the south.

The geographical scope investigated in this article focuses on the southeastern part of Hebei Province. This region, lying at the junction of Hebei, Shandong, and Henan provinces, still witnesses the inheritance of local Daoism in a vibrant form. Despite local Daoism’s gradual decline in recent times, a substantial number of local Daoist documents have been retained here, and the complete traditions of “

jiao” (醮, offerings) rituals and “

zhai” (齋, retreats) rituals are also preserved. In the local religious life, there exists a type of ritual experts with sectarian traits, known as the “merit-delivering masters” (

biaogong shifu 表功師傅)

5, who coexist with local Daoist priests in the venues of

jiao rituals and offers religious services to the public on different fronts. In this religious ecosystem, Daoism does not exist independently; instead, through long-term integration and interaction with popular religions

6, Daoist rituals and texts that possess increasingly distinct local characteristics have come into being.

7Between 2013 and 2022, we carried out field recordings on numerous jiao and zhai rituals of local Daoism. Moreover, we gathered a combined total of 102 ritual manuals and documents. These existing Daoist ritual texts and documents indicate that the local ritual tradition is the result of historical transformation. This transformation is mainly manifested in the following two dimensions: vertically—the succession of Daoist; horizontally—the circulation and integration among Daoist lineages. Therefore, based on the scriptures, Daoists’ oral histories, and ritual records collected during fieldwork in the southeastern Hebei region, this article sorts out the transformation process of the local Daoist ritual tradition in the area since the Ming and Qing dynasties through the aforementioned vertical and horizontal dimensions, and analyzes the factors influencing its transformation.

2. A Brief History of Daoism in Southeastern Hebei Since the Jin and Yuan Dynasties

The geographical scope of this study focuses on the southeastern region of Hebei Province. This region has been the southern part of Zhili 直隸 since the Ming and Qing dynasties. It includes areas such as Pingxiang 平鄉, Julu 鉅鹿, Nanhe 南和, Guangzong 廣宗, Quzhou 曲周, Jize 鷄澤, Weixian 威縣, etc. According to the current administrative division, this area mainly covers ten counties in the eastern part (dongba xian 東八縣) of Xingtai 邢臺: Renxian 任縣, Nanhe, Pingxiang, Julu, Guangzong, Weixian, Linxi 臨西, Qinghe 清河, Nangong 南宮, and Xinhe 新河, which together form the scope of the study in the modern administrative context.

Based on the existing materials, within the counties and districts situated in the southeastern part of Xingtai, Daoist activities have been thriving since at least the Jin and Yuan dynasties. There was a considerable number of traces left by the activities of Daoist priests have endured over time and remained to this day. According to the records in the local chronicles, Xiao Jingxing 蕭淨興, a female Daoist in the Jin dynasty, won the special favor of the emperor due to her remarkable ability to predict events and even managed to enter the emperor’s dreams. The Daoist temple where she lived was honored with the title of “Wuji Abbey” 無極觀, and she came to be known as Immortal Xiao 蕭仙姑 among later generations.

8 Moreover, the “Epitaph of Li Shoutong” 李守通墓表 included in

Selected Literary Works of Guangzong 廣宗文征 records that three generations of the Li 李 family were all Daoists.

9During this period, as the extant materials have already demonstrated, the Quanzhen School of Daoism in the local region witnessed a rapid development and showed clear indications of prosperity. The “Stele of Bixu Abbey” 碧虛觀碑 erected in the ninth year of the Zhiyuan 至元 reign period (1272) documented that Guo Zhidao 郭志道, the first abbot of the Bixu Abbey in Beisiguo Village 北寺郭村, founded the temple and gained Yin Zhiping 尹志平’s admiration and was conferred with the name of Zhidao 志道 and the title of

Baozhenzi 保真子 due to his accomplishment.

10 There was once a Datong Abbey 大同觀 in Dabaishe Village 大柏社, and the existing inscriptions on the steles vividly document the circumstances in which the whole family of Li 李 delved into Daoism and had disciples spreading far and wide at that time.

11Within this time frame, a multitude of Daoist activities were regularly held in this region, among which the Quanzhen School of Daoism enjoyed a spell of remarkable popularity. In addition to the Daoist temples metioned above, a lot of Daoist temples were built by Quanzhen Daoists, such as Qixia Abbey 栖霞觀 in Zhanggu Village 張固寨, Sanqing Temple 三清殿 in the west of Liqing Village 李清村, Tianxian Abbey 天仙觀 in Yecun 冶村, Bixia Abbey 碧霞宮 in Jianzhi Village 件只村, Shuang-ling Abbey 雙靈觀in Huocheng Village 霍城寨, Queshan Holy Mother’s Palace 鵲山聖母行宮 in the north of Chizhang Village 斥樟村, and City God Temple 城隍廟 in Guangzong County.

12In the Ming and Qing dynasties, Daoist priests in temples participated in the religious life of local society. And county chronicles recorded that Daoist priests provided funeral rituals for the people.

13 In the seventeenth year of Hongwu period 洪武 of the Ming dynasty, Guangzong County set up the Daoist Administrative Department 道會司 (

daohui si), along with the position of director 會長 to oversee local Daoist affairs which was stationed in the City God Temple of the old county seat.

14 There were Daoist living in the temple all the year round. Every month throughout the year, the City God Temple had different sized Daoist rituals.

15 Some nearby Daoist temples were also popular, such as the Lingying Temple 靈應觀 in Julu County.

16By the end of the Qing dynasty,

daohui si was abolished, and the prosperity of Daoist temples was no longer as it used to be. In the early years of the Chinese Republic (1911–1949), the government confiscated temple properties. Moreover, many temples in Guangzong and surrounding counties were destroyed. The activities of Daoists and local monks were restricted, which also led to the conversion of monks and Daoists to secular life. Between 1920s and 1930s, there were merely several Daoist residing in the temples, yet numerous lay Daoists were scattered across the villages. In the late 1930s, in Guangzong County alone, “around one-fourth of the villages were home to lay Daoist priests, with an approximate total of 260 people.”

17 In addition, as documented in relevant documents, “The official activities organized by Daoist associations came to an end, yet

jiao rituals and the chanting scriptures (

nianjing 念經) during funerals remained rather prevalent.”

18 A substantial number of Daoist priests from Daoist temples poured into the folk community and continued to offer two types of ritual services, specifically, conducting

jiao rituals and performing rituals for the salvation of the deceased.

The

jiao rituals in villages were interrupted after 1937, and during the “Cultural Revolution” 文化大革命, most of the ritual items and scriptures of local Daoist priests were either confiscated or burned. As local Daoist priest Wang Junying 王俊英 (b.1947)

19 recounted, since the “Smashing of the Four Olds” 破四舊 started in 1964, local Daoist activities had decreased, and in 1965, the government explicitly banned all religious activities. However, it was not until the late 1970s that due to the demand for salvation rituals in the village, Wang Junying, together with his master and fellow disciples, secretly went to the bereaved families to chant scriptures for the salvation of the deceased.

20In the early 1980s, over 20 elderly Daoist priests gathered at the home of Zhang Haichao 張海潮, a Daoist in Zhongqing Village 中清村, to sort out the incomplete ritual manuals by rearranging and transcribing the contents of the scriptures from their memories. They named this activity “Flag-Erecting Ritual Field” (liqichang, 立旗場), which lasted for seven days.

After the mid-1980s, local ritual traditions revived along with the intangible cultural heritage movement 非物質文化遺產. In contemporary times, there are three main Daoist lineages in southeastern Hebei: the Longmen lineage 龍門派 (local talk of “

Qiuzu pai” 邱祖派), Wudangshan Langmei Xian lineage 武當山榔梅仙派 (“

Sunzu pai” 孙祖派), Huashan lineage of 華山派 (“

Haozu pai” 郝祖派).

21 Until 2010s, the existing Daoists of the Longmen lineage are the 20th to 22nd generation, the Langmei Xian lineage are the 28th to 29th generation, and the Huashan lineage are the 25th generation. The lineages of Langmei Xian and Longmen are prosperous relatively, while the Huashan lineage has declined.

Daoists in Southeastern Hebei are divided into group of civil (

wen 文) and martial (

wu 武).

22 Civil group refers to the ritual masters including high priest (

Gaogong 高功),

Tike 提科, and

Biaobai 表白

23; Martial group refers to the instrumentalist playing music. Each Daoist starts with learning martial arts and subsequently progresses to advanced civil knowledge. This implies that even those within the civilian group are acquainted with how to play Daoist music. Learning the martial section (

wu) of Daoist rituals requires five to six years. Afterwards, based on each disciple’s strengths, the master will select a small number of suitable Daoists to learn the civil section (

wen)—that is, the role of the

Gaogong.

3. The Existing Varieties of Daoist Rituals and Texts

3.1. The Existing Varieties of Daoist Rituals in Southeastern Hebei

There are two existing categories of Daoist ritual in the southeast region of Hebei: the jiao ritual and the zhai ritual for the salvation of the deceased 度亡.

The

jiao ritual refers to the “

jiao ceremony” (local called “

da jiao” 打醮) in villages which occur from the tenth lunar month to the second lunar month of the following year. The origin of the tradition of “

da jiao” can no longer be traced nowadays. As the

Wei County Gazetteer 威縣志, which serves as the earliest accessible documentary source concerning the local

jiao ceremony, recorded in the eighteenth year of the Republic of China that “Whenever a person died, people usually invited Daoist priests to chant scriptures, and during festivals and holidays, they often held

zhai and

jiao rituals (凡人死每招道士誦經,歲時每起齋醮。)”, it can be deduced that as early as in the initial period of the Republic of China, the

jiao ceremony had already taken root as a tradition among the villages in the southeast region of Hebei.

24In the local area, the

jiao ritual is a village-based community collective ritual, where Daoist priests act as ritual experts and provide a framework for its ritual systems.

25 The “

da jiao” can be categorized into two types, namely the “village

jiao” 村醮 which aims to bestow blessings upon the entire village, and the “consecration

jiao” 開光醮 that is held upon the completion of a new temple. The “village

jiao” is typically conducted once every other year, although in some villages, it may be held once every three or five years. As for the “consecration

jiao”, it is a ritual held annually for three consecutive years commencing from the time when a new temple is completed.

The zhai ritual for the salvation of the deceased, which is another religious ritual of great significance in the local society, plays a crucial role. This ritual involves constructing a ritual site for the bereaved families with the aim of helping the deceased transcend the netherworld. It is a frequently held religious activity locally and is commonly called as “handling funerary affairs” 做白事 or “chanting scriptures” 念經. Given that when most elderly villagers pass away, their families generally invite Daoist priests to organize the funerals, this ritual is held with a much higher frequency than the village jiao. As a result, a local Daoist priest participates in more rituals for the salvation of the deceased than in the da jiao within a year. In this way, the ritual for the salvation of the deceased, together with the da jiao, forms a complete set of local Daoist rituals in the southeast region of Hebei.

3.2. Collection and Catalog of Extant Daoist Texts

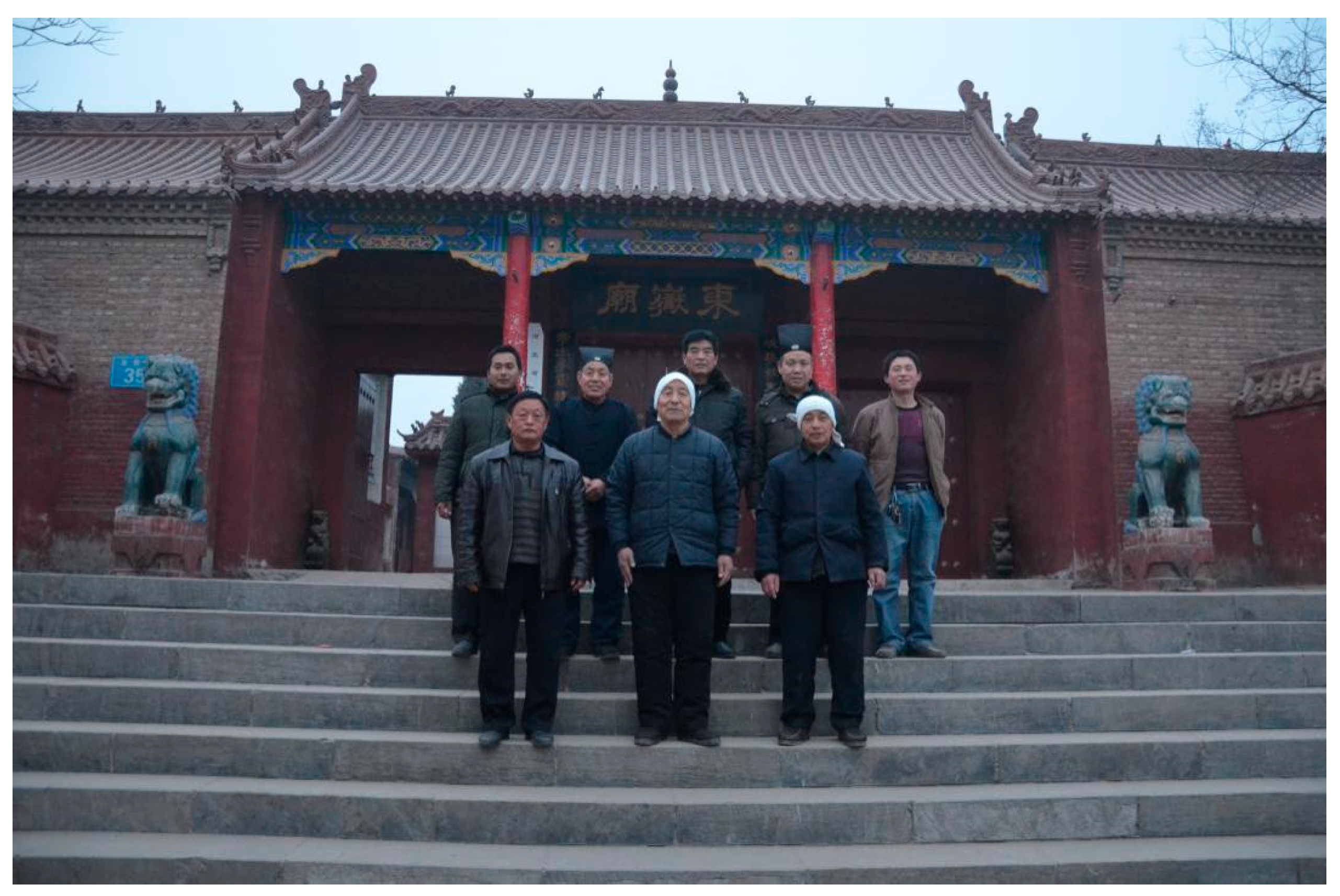

The study in this article has collected a total of 102 liturgical manuals.

26 These collected Daoist literature mainly consists of liturgical manuals, sourced from the Langmei Xian lineage and the Longmen lineage. Its source comes from five Daoist ritual masters (

Gaogong) in local villages—Li Junshi 李俊師

27, Zhu Zebao 朱澤寶

28, Zhang Jiaohua 張教華

29, Lu Haiyan 盧海燕

30, and Zhang Yubao 張玉寶

31, and as well as the collection of the Hegumiao Temple Committee 河古廟廟委會 (

Figure 1). Among them, Li Junshi (29th generation), Zhu Zebao (29th generation), and Zhang Jiaohua (27th generation) were Daoists of the Langmei Xian lineage, while Lu Haiyan and Zhang Yubao were Daoists of the Longmen lineage of the 20th generation.

According to the purpose of these texts, they can be classified into three categories based on practical purpose: liturgy for the living (Qing Shi 清事) and for the dead (Ji Du 濟度), and miscellany 雜集. Wherein, there are 32 types of liturgical manuals and documents in the liturgy for the living, and there are a total of 100 different versions. According to the category of the ritual, it is classified as follows: opening scriptures and borrowing land (Kaijing Jiedi 開經借地), prohibiting wind and water intake (Jinfeng Qushui 禁風取水), receiving land and city gods(Jie tudi chenghuang 接土地城隍), issuing documents (Fawen 發文), raising flags (Yangfan 揚幡), the Heavenly Master worship (Qishi 啓師,) settling the gods for supervising sacrifice ritual (Anjian 安監), inviting the five elders (Qing Wulao 請五老), sacralizing water edicts (Chishui 勅水), burning and dispensing lamps (Fendeng 分燈), inviting the three treasures and enchantment (Jiesanbao, Anzhen 接三寶與安鎮), inviting the sun (Qing Taiyang 請太陽), transferring scriptures (Zhuanjing 轉經), reciting for Beidou (Beidou Zuo 北斗座), dividing guard of honor (Fenban 分班), cult for the three treasures (Xinli 信禮), offering incense of the five grades (Wupin Shangxiang 五品上香), the three homages hymn (San Guiyi 三皈依), celebrating longevity (Zhushou 祝壽), litanies (Baichan 拜懺), memorial presenting (Baibiao 拜表), offering for forbidding hail (Jibing 祭冰), meeting the pardon (Jieshe 接赦), dispatching the pardon (Fangshe 放赦), seeing off the five elders (Song Wulao 送五老), seeing off gods (Songshen 送神), settling the gods (Anshen 安神), guarding houses (Zhenzhai 鎮宅), mantras (Zhou 咒), documents 文書 (Guan 關, Biao 表, Die 牒, Bangwen 榜文, couplets 對聯), talismans (Fu 符), ritual regulations (Guizhi 規制), and Daoist music manuals 道樂曲本.

There are 8 types of liturgical manuals for the dead, with a total of 21 different versions. According to the purpose of the ritual, it could be classified as follows: bestowing food ritual (Shishi 施食), the Ten Kings hymn (Zan Shiwang 讃十王), sending off to the Twelve Cities (song shier cheng 送十二城), smashing the hells (Poyu 破獄), bathing ritual (Muyu Chaocan 沐浴朝参), opening scriptures (Kaijing Bajian 開經拔薦), crossing the bridges (Duqiao 渡橋), and death ritual lyrics 度亡曲詞.

Miscellany consists of a total of 10 books. The content is complex, involving self-cultivation in the morning and evening (Zaowan Gongke 早晚功課), incense divination (Guanxiang 觀香), praying for rain (Qiyu 祈雨), and genealogies of past masters (Lidai Fashi Zongpu 歷代法師宗譜).

The above texts are mainly based on handwritten copies. The time span of the version is from the 8th year of the Qing Tongzhi 同治 reign to 2013. There are multiple copies of the same legal content with different texts. The phenomenon of homophones but different characters, as well as misspellings and errors, is quite common. There are two ways to re-generate handwritten copies. One is the transmission between different documents, and the other is the translation of oral scriptures into written form. In the inheritance of local Daoism, oral transmission is the mainstream means. This type of manuscript is a written record of the content of Daoist Gaogong, therefore it has certain local characteristics and oral attributes.

4. Vertical Transmission of Ritual Texts: The Case of the Langmei Xian Lineage

4.1. Daoist Lineage and Dimension of Transmission

Up to the present day, dozens of Daoists of the Langmei Xian lineage remain active in this local area, referring to themselves as the “

sunzu pai”. Through the comparative investigation of Hegumiao Temple 河古廟 inscriptions, folk literature, and field interviews, we have sorted out the history of the transmission of the Langmei Xian lineage in southeastern Hebei since the Ming dynasty which is the earliest evidence of the remnants of the Wudangshan Daoist lineage 武當山道派in the southeastern region of Hebei Province. It can be inferred that the Langmei Xian lineage had spread northward to Hebei no later than Ming dynasty.

32 The succession line of master-disciple and ritual text versions have demonstrated the vertical transmission and changes in local ritual traditions and scriptures.

The local Daoist priests in Guangzong believe that “the Daoists in Guangzong have their roots in Pingxiang”

33, where the “root” means the Hegumiao Temple in Pingxiang county, the main temple for local Langmei Xian lineage Daoists. According to the examination of the remaining stele inscription

Records of the West Corridor Temple 西廊廟記 in the temple, Hegumiao Temple had existed by the fourth year of the Zhida 至大 reign in the Yuan Dynasty at the latest.

The lineage verse (

paishi 派詩) presently employed by the local Langmei Xian lineage is: “碧天(山)傳日月,守道合自然。性理通玄德,清微古太原。真靜常悠久,宗教福壽長。慶雲衝霄漢,永遠大吉昌。” This is consistent with the Langmei Xian lineage’s poetry in the

Comprehensive Register of All Genuine Lineages 諸真宗派總簿 stored in the White Cloud Abbey 白雲觀 in Beijing.

34During the Tianqi 天啓 period (1621–1627) of the Ming dynasty, Hegumiao Temple was renovated.

35 There is also a clear record of Langmei Daoist priests once managing in Hegumiao Temple. The existing temple stele “

Shundefu pingxiangxian hegucun *miao tushenji (順德府平鄉縣河固村口廟圖神記)” was built in the sixth year of the Tianqi (1626). At the end of the stele, the names of the Langmei Xian Daoist appeared on the inscription: “The Daoist Duan Xingli 段性禮 in charge, Li Liqing 李理清 and Li Lijing 李理敬 as disciples”. Based on the lineage verse of the Langmei Xian lineage, Duan Xingli, an 11th-generation Daoist priest, was the abbot in charge of the Hegumiao Temple and his two disciples were of the 12th generation, which is the earliest record of the Langmei Xian Daoist priests in existing materials in southeastern Hebei.

The Daoist tradition of Hegumiao Temple remained as the Langmei Xian lineage during the Kangxi reign 康熙 of the Qing Dynasty. There is a stele in the temple dating back to the 18th year of the Kangxi reign (1679), titled “Stele Inscription of the Gilded Icons of the Entire Assembly in the Granny’s Hall of Hegu Temple, Pingxiang County, Shunde Prefecture, Zhili “ (直隸順德府平鄉縣河固廟奶奶殿金妝合堂聖像碑記) which indicates that by the Kangxi reign, the Langmei Xian lineage had developed into the 14th generation of Xuan 玄, 15th generation of De 德, and 16th generation of Qing 清 Daoists in the area, and there were resident Daoists in the temple.

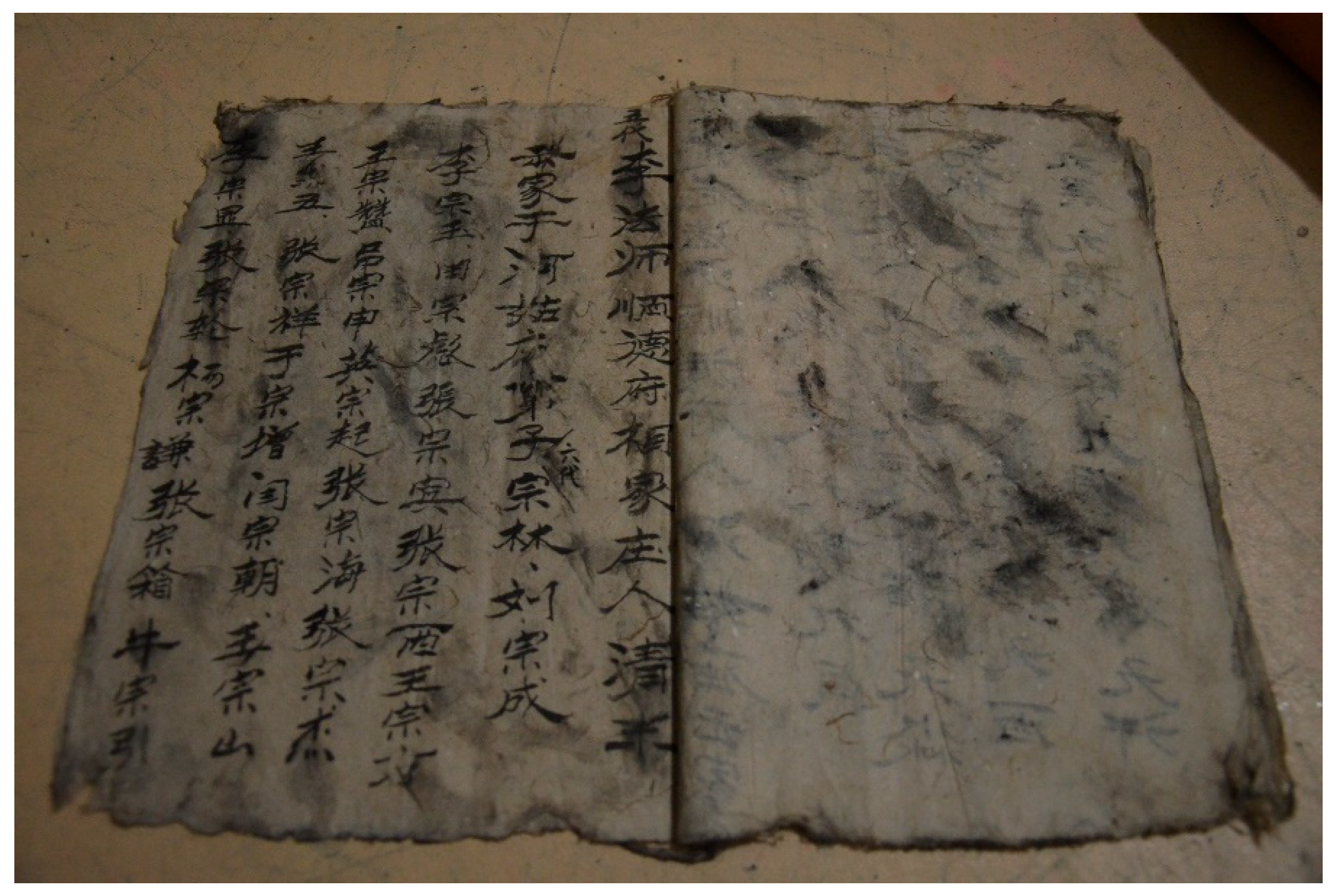

The Hegumiao Temple currently collects a genealogy of

Five Generations of Master Priests (五代法師), with its compilation date unknown (

Figure 2). The Daoist priests in the temple believe that this is the inheritance genealogy of the Langmei Xian lineage at Hegumiao. This genealogy records the names of Daoist master priests from the 21st generation (“

zhen 真” character generation) to the 25th generation (“

jiu 久” character generation) and the list of their disciples in the region. No compiler’s name is recorded in

Five Generations of Master Priests, but based on the list, it can be inferred that it was compiled by a Daoist priest of the 25th generation or the 26th generation (“

zong 宗” character generation). According to Zhang Jiaohua, a 27th-generation Daoist priest, Master Li Jiuqin 李久勤, the 25th-generation Daoist recorded in the genealogy, was their grandmaster. Li Jiuqin accepted more than 130 disciples in his lifetime and was renowned as the top Daoist priest in southern Hebei at that time.

36 Niu Zonglin 牛宗林, the master of Zhang Jiaohua, became a disciple of Li Jiuqin in the early years of the Republic of China, and later passed down the mantle to Zhang Jiaohua and others in the late 1950s.

Another genealogy titled Six Generations of Master Priests 六代法師 is preserved in the temple, compiled by Niu Zonglin. Building on the content of Five Generations of Master Priests, this genealogy adds the list of 26th-generation Daoist of the “zong” character generation. Zhang Jiaohua possessed two genealogies compiled in modern times: one is Master Priests of Successive Generations 歷代法師, which adds the list of 27th-generation Daoist of the “jiao 教” character generation based on the content of Six Generations of Master Priests; the other is Eighteen Generations of Master Priests 十八代法師, which supplements the list of 28th-generation Daoist of the “fu 福” character generation on the basis of previous versions.

In addition to the above Daoist genealogies, the copying inheritance of the Langmei Xian lineage can also be reflected in the ritual texts held by Gaogong in this region. Among the ritual manuals in the collection of Zhang Jiaohua, the Complete Liturgical Text of the Great Master 大法師全科本 was re-copied in the contemporary era. Two inscriptions of the copyists from previous versions are preserved in this ritual manual: the first is in the middle part: “copied by Master Qin 勤當家 on the 9th day of the 1st lunar month in the 15th year of the Guangxu 光緒 reign “ (勤當家抄於光緒十五年端月玖日), and the second at the end: “copied by Master Chang 常當家 on the 3rd day of the 3rd lunar month in the 8th year of the Tongzhi 同治 reign “ (同治捌年桃月叁日常當家抄). This information verifies the existence of Li Jiuqin 李久勤, the 25th-generation Daoist, and the “Chang 常” generation Daoist of the 23rd generation, as well as demonstrating the inter-generational inheritance of liturgical texts among Langmei Xian lineage Daoists. It also indicates that the ritual texts had already circulated among the Daoist priests of the Langmei Xian lineage in southeastern Hebei by the Tongzhi reign period at the latest, were recopied again during the Guangxu reign period of the late Qing dynasty, passed through the Republic of China, and have been transmitted to the present day. It can be said that the version transmission of the existing Complete Liturgical Text of the Great Master corresponds to the historical lineage of the Langmei Xian lineage.

4.2. The Origins of the Ritual Texts of the Langmei Xian Lineage in the Contemporary Era

Currently active among Daoists of the Langmei Xian lineage in southeastern Hebei are those generation of the 27th

jiao character, the 28th

fu character, and the 29th

shou character. Most Daoists of the

jiao character generation were born before the 1950s. Currently, the Daoists who can still perform rituals are mainly those of the

fu and the

shou character generation. They are distributed at the junction of Guangzong, Pingxiang County in Xingtai and Handan City, with the majority residing in Guangzong and Pingxiang. In 1985, Guangzong County conducted a statistic showing that “there were still 27 Daoist priests of the

Sunzu pai 孫祖派 in the county, mainly distributed in villages such as Zuanyao, Dapingtai, Shaowa Zhuang, Dasanzhou and Nanxiaolu, and their patriarch resided in Hegumiao, Pingxiang County.”

37In this study, representative Daoists were interviewed among the three generations of the jiao, fu, and shou, namely Zhang Jiaohua, Li Junshi, and Zhu Zebao. As Gaogong, they were active at ritual sites (Zhang Jiaohua passed away in 2018). Most of the ritual texts in their collection are derived from the versions preserved in Hegumiao Temple and those handed down by their masters.

When Zhang Jiaohua was alive, he was the Daoist priest who possessed the largest number of ritual texts there. Some of his texts were inherited from his master Niu Zonglin and other 26th and 27th-generation priests of the same lineage. Zhang Jiaohua was born into a peasant family. He began to learn the craft at the age of 12, starting with the bronze instruments for the sound of rituals, and did not formally apprentice to Niu Zonglin until he was 14 years old. Zhang inherited several ritual texts from his master in Hegumiao, along with some Daoist ritual implements. During the Cultural Revolution, Zhang Jiaohua hid the ritual texts in a cellar, enabling them to be preserved to this day. In 2006, the Government of Guangzong County named nine local Daoist priests as Outstanding Inheritors, and Zhang Jiaohua was included in the list due to his extensive collection of materials.

Today, the main Gaogong are Li Junshi and Zhu Zebao of the shou character generation. The ritual texts copied by them are derived from the collections of Zhang Jiaohua and the Hegumiao Temple. The transmission of ritual texts by Li Junshi and Zhu Zebao reveals an interesting phenomenon there—their ritual texts are not derived from their own masters. This involves two types of master-disciple inheritance in southeastern Hebei: formal apprenticeship (拜師) and technique Learning (學藝).

4.3. Apprenticeship and Technique Learning: The Vertical Medium of Scripture Circulation

Formal apprenticeship and technique learning are the vertical media for the transmission of scriptures of the Langmei Xian lineage in Southeast Hebei. Both constitute a master-disciple inheritance relationship, within which the intergenerational transmission of ritual texts between master and disciple is accomplished. Apprenticeship is related to the identification of Daoist lineage, while technique learning refers to ritual traditions. Different lineages may have inherited the same ritual traditions, and individuals within the same lineage may also have inherited different ritual traditions. There is no fixed correspondence between Daoist lineages and ritual traditions in terms of names and objects.

In terms of actual apprenticeship, local Daoists have a clear distinction between “apprenticeship” and “technique learning”. Unlike Daoism in Southern China, there are no organizational units such as Daoist altars 道壇 or family altars 家壇. They inherit the Daoist lineage’s verse by formally acknowledging the senior Daoists as masters. This kind of master apprentice relationship usually occurs within the same village, so some villages have a larger number of Daoists, while others have fewer or even no Daoists. A Daoist usually only performs one “apprenticeship” ceremony and recognizes one Daoist as his master. When formally acknowledging one’s master, it is necessary to be introduced by an introduction master 引薦師

38, sponsored by a guarantor 送保師, and after obtaining the master’s acceptance, the acknowledgement ceremony can be held. On the day of acknowledgement ceremony, the disciple must write a letter of apprenticeship, which reads: “Please introduce the teacher (name), master (name), disciple (name), and guarantor (name) on the date of the year. “The disciple raises the apprenticeship token to his head, and the master takes it. After the disciple kowtows to the master, it is considered as a satisfactory accomplishment. According to the rules, one cannot acknowledge their own parents or brothers as masters.

39 Technique learning can follow multiple masters, and the rules are also relatively relaxed. In addition to learning from Daoist priests in the same village, there are also examples of Daoists who went to different villages and counties to learn from famous Daoist priests.

As the main Gaogong in southeastern Hebei today, Li Junshi and Zhu Zebao apprenticed to Wang Junying 王俊英, a Daoist of the 28th generation of Langmei Xian lineage from the same village, at the age of 13, and obtained their Daoist names of the shou character generation. Wang Junying excelled in Daoist music performance (Martial group) but had no knowledge of civil group content. After studying instrumental music performance under Wang Junying for several years, Li and Zhu hoped to learn the content of the Gaogong. Therefore, the two began to learn from Gaogong masters such as Zhang Jiaohua, inheriting the content of their ritual texts. Through text comparison, it can be seen that based on remaining faithful to the original versions, Li Junshi and Zhu Zebao added notes and remarks to the copied, taking into account the orally—transmitted content or the actual needs of rituals.

The inheritance context of the Langmei Xian lineage in southeastern Hebei shows us the vertical path of local Daoist priests’ transmission of ritual texts. On the other hand, the distinction between their formal apprenticeship and technique learning indicates that local Daoist have a certain degree of openness in the ways they inherit the content of ritual texts and ritual traditions. This openness is reflected in Daoist priests’ choice of inheritance content based on ritual practices and needs. What they inherit is not only the Daoist name of a Daoist lineage, but more importantly, the content of ritual texts.

5. Horizontal Circulation of Ritual Texts: Sharing and Integration Among Daoist Lineages

5.1. The Cooperation Mode of Local Daoist Priests: Daoist Groups (Daoban 道班)

Since the mid-Qing dynasty, the lineage of Langmei Xian, Longmen and Huashan, and have coexisted for a long time in the southeastern region of Hebei and have all participated in local Daoist religious activities.

Although the local Daoists inherit the lineage name centered around the Daoist lineage, they organize their religious practices solely around the Daoist groups in activities and usually perform ritual together. They usually cooperate by organizing Daoist groups which are formed freely and have a rather loose organizational structure, depending on the requirements of rituals. The organizer contacts a familiar Daoist to put together the group and act as the “group master” 班主, who then invites other Daoists based on the ritual’s scale. When holding a jiao ceremony or dealing with a funeral service, the ritual is categorized as “half altar” 半壇 (with 12 Daoist priests participating, including one Gaogong, one Tike, one Biaobai and nine martial Daoists playing music) or “full altar” 全壇 with 24 Daoist priests participating.

In the rituals of jiao and zhai, the identification of the Daoist lineage tends to be diluted. To put it more precisely, through cooperation in these rituals, a tacit understanding has been formed among the participants who adjust according to their collaborators. It is commonplace for Daoists from different lineages to collaborate with each other in rural Hebei. From the perspective of division of labor, these differences in ritual process are more obscured by their cooperative performance.

5.2. Integration of Daoist Lineage in Liturgical Manuals

In this study, the earliest surviving manuals of the Langmei Xian lineage we could found in east southern Hebei whose date in the traditional calendar is equivalent to the 1860s, while the date of earliest surviving manuals of the Longmen lineage is 1980s. As far as copying time is concerned, it can be concluded that the Langmei Xian lineage had already practiced local Jiao and zhai by the 1860s at the latest. It is unknown that when the Longmen lineage first started performing rituals.

By comparing and analyzing the contents of the scriptures collected by Daoist priests from Langmei Xian and Longmen, we could discover their Daoist characteristics in the details. In the manuscript of the Complete Liturgical Text of the Great Master collected by Zhang Jiaohua mentioned above, the collection of Chishui ke 敕水科 in Qisheng 啓聖 section, Gaogong firstly requires inviting highest-level gods such as Three Pure Ones and Six Heavenly Emperors 三清六御 and then inviting True Masters of Past Dynasties 歷代師真. Among them, the title of Revered Master, the Lord of Ten Thousand Dharmas, Supreme Thearch of Dark Heavenr 恩師萬法教主玄天上帝 appears. This title of “Revered Master (en’shi 恩師)” also appears in Zhang Yuanqian 張元霙’s “sacralizing water edicts for ritual master” 法師本勅水 (collected by Zhang Jiaohua, the copied year is stamped, later with the words “Zonglin 宗林 1927”). The Chishui ke 敕水科 copied by Li Junshi in 2000, also inherits the sacred content of “Revered Master, the Lord of Ten Thousand Dharmas, the Supreme Thearch of Dark Heaven 恩師萬法教主玄天上帝”. The Langmei Xian lineage of Wudangshan traditionally worships the Perfect Warrior 真武 (also titled Supreme Thearch of Dark Heaven 玄天上帝) as its main worship and refers to themselves as disciples of Perfect Warrior. Therefore, the title of “en’shi 恩師” to Supreme Thearch of Dark Heaven reflects the characteristics of this lineage.

The “Lingbao xiujiao qishuike” 灵宝修醮啓水科 (the ritual content involves “sacralizing water”) collected by Zhang Yubao, a Daoist of the Longmen lineage, has a different manual name from the Langmei Xian’s scripture. However, the content of 灵宝修醮啓水科 is almost identical to the above three Chishui ke manual owned by the Langmei Xian lineage scripture. It also invites the Revered Master, the Lord of Ten Thousand Dharmas, the Supreme Thearch of Dark Heaven during the Qisheng 啓聖 section. Therefore, based on the content of the liturgical manuals and the time of the handwritten manuscripts discovered today, it can be inferred that some of the liturgical manuals copied by contemporary Longmen Daoists are from the Langmei Xian lineage.

In terms of the signing time and the content of some liturgical manuals, the copied texts of the local Langmei Xian Daoists were earlier than those of Longmen. These scriptures have also been passed down to a certain extent as sources within the Daoist community of the Longmen lineage. However, it is important to note that although the ritual content copied is generally consistent, there are still differences between their respective lineages when comparing the manuscripts of these two Daoist lineages. The most obvious difference lies in the section of ordination rank proclamation (

Chengzhi 稱職)

40 according to the handwritten manuscript of Li Junshi from the Langmei Xian lineage and Zhang Yubao from the Longmen lineage (

Table 1).

Through the above comparison belonging to the categories of Qingshi 清事 and Jidu 濟度, it can be seen that the two Gaogong in the section of Chengzhi reflect the characteristics of their own lineage: The Langmei Xian Daoists consider themselves as disciples of the Perfect Warrior, Longmen Daoists consider themselves disciples of Qiu Changchun 邱长春 correspondingly. It is worth noting that although there were instances of taking register called “receive the Daoist scriptures and registers of the Supreme Three-Five Metropolitan Merits” (参授太上三五都功经籙), contemporary Daoist priests in southeastern Hebei have not participated in any ordination ritual of registers. As a matter of fact, most Daoists were not clear about the ordination ritual of registers, which does not prevent them from practicing Daoist rituals. There is currently no material available to present the situation of local Daoist priests’ participation rate of ordination ritual of registers before the present days.

However, the characteristics of Daoist lineage are limited to the ritual sessions before “the Invoking the Ancestor” (

Qishi 啓師) and “the Invoking the Heavenly Master” (

Qing Tianshi 請天師). If the Heavenly Master has already been invited to the altar, the

Gaogong belonging to different Daoist lineage correspondingly call themselves as “disciples of Heavenly Master Zhang” (張大真人門下弟子). Take the libretto of “the Lamp-Distributing” (

fendengke 分燈科) as an example,

“When I think of The Jade Pool and heaven, I extremely eulogize it. I am a disciple of Heavenly Master Zhang, the leader of the Dragon Tiger Immortal Mountain of Jiangxi, and I have been entrusted by the register called the Supreme Three-Five Metropolitan Merits. I will follow the standards of ritual practice and performed memorial presenting ceremony by burning lamps today. I have also performed rituals at the same altar to gather kindhearted people and other believers. I am filled with awe and trepidation towards my responsibilities.” (一念瑤天,吾體投地。臣系江西虎光福地敕奉龍虎仙山天師教主張大真人門下弟子,參受太上三五都功經籙,以科奉行科範,以今焚燈進表小兆事,(臣)同壇下修醮以會眾善人等,各職無任隍誠誠恐稽首頓首。)

After the section called “Sending off the Heavenly Master” (song tianshi 送天師), the Gaogong were qualified according to the content of their respective Daoist lineage. Ritual content and process is highly clear and standardized by local Daoists that has been practiced to this day.

By comparing the contents of ritual manuals belonging to different Daoist lineage, it is preliminary inferred that the Longmen lineage borrowed the liturgical manuals of the Langmei Xian lineage (

Figure 3). The local Longmen Daoists made corresponding modifications to the relative sections based on the literature of the Langmei Xian lineage. This explains why the Daoists of these two Lineages can collaborate during the ritual. The

Gaogong of the two lineages have a common source as mentioned above, while the local Daoist music that martial arts used are the same. From the perspective of ethnomusicology, it is difficult to distinguish between the above two Daoist lineages.

Through the above analysis of the liturgical manuals and practical apprenticeship aspects, the relationship between various Daoist lineages in the local area is characterized by similarities but differences. Therefore, with respect to the Daoist ritual tradition in the southeastern region of Hebei, although the existing three lineages of have different lineage verses as well as the certain rituals, their inherited literature and ritual processes are highly integrated. Daoists from various lineages can collaborate to complete the same ritual. In the collaboration of the ritual practice, the Daoists of these three lineages recite scriptures and perform rituals together. The martial groups share the same music system of which the rhyme and melody in the ceremonial singing of the literary scene are also homogeneous.

6. Conclusions

This article takes Daoist ritual texts in southeastern Hebei since the Ming and Qing dynasties as the research object. Based on the fieldwork data collected from 2013 to 2022, it sorts out the transformation of the local Daoist ritual traditions from the dual perspectives of vertical transmission and horizontal dissemination. The landscape presented by local Daoism in southeastern Hebei shows that the transformation of ritual texts in this region is not a linear replacement but relies on the mutual infiltration of inter-generational transmission and traditions among Daoist lineages.

From the vertical perspective, the transmission of ritual texts of the Langmei Xian lineage clearly presents the inheritance context of local Daoism. By the Tianqi period of the Ming dynasty at the latest, the Langmei Xian lineage had spread northward to southeastern Hebei, forming a stable Daoist lineage with Hegumiao Temple as its ancestral court. Its generation-character poem is mutually corroborated by Comprehensive Register of All Genuine Lineages from the White Cloud Abbey in Beijing. The inheritance lineage from the 11th-generation Daoists in the Ming dynasty to the existing 27th, 28th and 29th-generation Daoists is completely verifiable. Based on the textual research of the content of existing ritual texts, they were copied by the 23rd-generation (chang character generation) Daoists no later than the Tongzhi period of the Qing dynasty and have been passed down to the present day. What is particularly special is the local dual transmission model of “establishing Daoist lineage affiliation through formal apprenticeship and inheriting ritual practice through technique learning”, which endows the transmission of ritual texts with both stability and openness: Daoists establish their lineage identity through formal apprenticeship, while being able to learn ritual practice from senior Gaogong across villages and counties. This kind of model not only ensures the inter-generational continuity of the core content of rituals but also provides flexibility for the supplementation and revision of texts according to practical needs—and the inheritance relationship between Zhang Jiaohua’s collected version and the copied versions by Li Junshi and Zhu Zebao serves as a typical example.

On the level of horizontal dissemination, the sharing of texts and integration of rituals among Daoist lineages constitute another core driving force for the transformation. The lineages of Langmei Xian, Longmen, and Huashan in this region have coexisted for a long time. In contemporary times, they conduct rituals with Daoist groups as organizational units, promoting the cross-lineage circulation of ritual texts. Text comparison shows that some ritual texts of the Longmen lineage share the same origin as those of the Langmei Xian. Differences are only realized by modifying lineage identifiers in the section of Chengzhi 稱職, while the instrumental music tunes of the martial group and the singing melodies of the civil group are completely consistent. The sharing of ritual texts among lineages at the practical level enables Daoists from different lineages to collaborate in completing rituals, forming an implicit collaborative and symbiotic relationship. In this process, ritual texts are no longer exclusive symbols of Daoist lineages but have become a common medium for cross-lineage cooperation.

Overall, the transformation of Daoist ritual texts in southeastern Hebei is the result of the combined effect of the stability of vertical inheritance and the openness of horizontal dissemination. Its overall characteristics can be summarized in three aspects:

First, the transmission dimension takes the inheritance of the Daoist lineage as its core foundation, presenting the dual characteristics of the solidification of the genealogy and the adaptation in practice. But at the same time, technique learning—another model of ritual inheritance—breaks the barrier of single inheritance and achieves an organic balance between upholding tradition and activating practice.

Second, the dissemination dimension takes ritual collaboration as its practical foundation, constructing an integrated pattern where content sharing and identity distinction coexist. Ritual texts have thus transformed from lineage-exclusive symbols into a common medium for inter-lineage cooperation.

Third, the dual dimensions of transmission and dissemination have jointly constructed the core mechanism for the formation of local Daoist ritual texts in southeastern Hebei. The interaction between the two has laid the structural and dynamic foundation for the formation, circulation, and evolution of ritual texts.