In the 19th century, the primary goal of missionaries in translating the Bible was to preach among the common people and attract a broad following. Their audience consisted largely of the lower classes, as noted by George Piercy of the British Wesleyan Methodist Mission in his 1861 Cantonese translation of Elementary Catechism: “Some may say that the ways of God are inherently profound, so why is this book written in such a vulgar style? How can it properly educate the young? Yet, it is deliberately made this simple to bring joy to the hearts of children and make it easy for them to understand.” 或者有人話,上帝嘅道理,原本好高深,做乜呢部書,講得咁粗俗,點樣教得嫩仔好呢?誰知特登做成咁俗,係攞個嘅內仔心中歡喜,易得明白嘅。 (

Hui Shi Li Tang 1862, p. 1). Similarly, the 1892 edition of

Gusu’s Journey published by Guangzhou Zhenbaotang Press stated: “The original text has been translated into the local dialect of Guangzhou. Although not every detail is fully captured, the main ideas are made clear. This edition is intended for women and children to read, allowing them to grasp the meaning both visually and intellectually.” 茲將原文,譯就羊城土話。雖未盡得其詳細,而大旨皆有以顯明。聊備婦孺一觀,了然於目,亦能了然於心。 (

Zhen Bao Tang 1902, p. 1). The readership of modern missionary novels exhibited distinct stratified characteristics, its core audience consisted of the lower-class populace, including women and children with limited literacy, who relied on vernacular narratives and illustrations to comprehend religious teachings; secondly, there were locally educated literati, whose identification missionaries sought to win by aligning Confucian ethics with the narrative form of chapter-based novels (

Yin 2013, p. 128); additionally, the readership included mission school students and the emerging urban citizen class, as these texts served dual functions of religious enlightenment and secular knowledge dissemination. Zhou Shimin points out that Cantonese-dialect missionary novels employed a “localized narrative strategy” to penetrate both rural communities and emerging urban spaces (

Zhou 2024, p. 156), forming a cross-cutting reader network that operated both “top-down” and “bottom-up.” The dissemination of these texts essentially constituted “a process of religious propagation and ideological permeation through cultural adaptation” (

Wu 2007, p. 215). Judging from this perspective, the target audience of missionary work was women and children with limited literacy; the use of novel illustrations in preaching proved more accessible than relying solely on religious textual narrative.

2.1. The Reception of the Sacred Edict Through Visual Imagery

To facilitate missionary work, the illustrations in missionary novels deliberately incorporated the ethical system of the

Sacred Edict, which was promoted by the Qing government. In late Qing Guangdong society, moral principles such as “loyalty, filial piety, chastity, and righteousness” and “encouraging virtue and reform” advocated by the

Sacred Edict, the

Sixteen Maxims, and novels based on the edicts had become important value standards for the public. “These principles extended from family ethics to economic life, and from educational concepts to legal norms, constructing the entire social order” (

Yang 2023, p. 17). Here, the term “sacred” (sheng) within the public belief system encompassed various entities, including the emperor; the founders of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism; and local deities. It relied on established ethical standards and values to persuade people to fully embrace goodness. As stated in the edict-themed novel

Tong Deng Dao An: “It seems that these two words, ‘sacred edict,’ are meant to exorcize ghosts and ward off evil. Even for a good person, they can still resolve grievances” 看來這聖諭二字,都是逐鬼驅邪的,為個好人,尚可解冤 (

Anonymous 1890, p. 24). This highlights the authority of edict-themed stories in society. The core of the sacred edicts was that “if one speaks for two or three days without discussing cases of loyalty, filial piety, chastity, or righteousness, it does not align with the sacred intention of teaching people to prioritize fundamental virtues. Such negligence may bring about blame, and this must be understood” 若宣講二三日而不論忠孝節義案者,則不符合聖神教人首重大本之意,恐自取罪戾,不可不知 (

Shuchizi 1887, p. 14). Thus, loyalty, filial piety, chastity, righteousness, harmony, and friendliness became key criteria of the sacred edicts.

Missionary novel illustrations adopted this framework by adding chapter titles and imitating the didactic style of the edicts, establishing a visual and textual system that resembled local ethics. For example, both The Pilgrim’s Progress in Vernacular (Continued) and The Pilgrim’s Progress in Vernacular contain thirty chapter titles each, closely linked to the Sacred Edict. Below are the titles from The Pilgrim’s Progress in Vernacular (Continued) as an example:

Recalling Father’s Admonition to the Son 憶父訓子; Attempting to Halt the Journey 欲阻行程; Commencing the Heavenly Path 始行天路; Lifting a Compassionate Heart 扶起心慈; Secretly Plucking the Forbidden Fruit 私摘惡果; Focused on Earthly Matters, Forgetting the Divine 顧下忘上; Observing Chickens to Expound the Dao 觀雞論道; Using Trees to Illustrate Human Nature 指樹言人; Escorting Travelers 護送行人; Displaying Corpses to Punish Evil 懸屍懲惡; Enduring Hardship Together 同歷艱苦; Advising Evildoers to Desist 勸止惡人; Welcoming into the Beautiful Palace 迎進美宮; Illness Met with a Skilled Physician 病遇良醫; Beholding Jacob’s Ladder 觀雅各梯; Reading a Stele for Warning 觀碑知警; Fearing Upon Encountering Demons 遇魔心怯; Inviting Others to Discuss the Dao 邀人論道; First Meeting an Honest Heart 初逢心直; Self-Doubt and Hesitation 自疑畏縮; A Traveler Sighs for Judah 客歎猶迦; A Woman Twice Welcomes the New 婦兩迎新; Bidding Farewell to Judah 辭別迦猶; Burning the Fortress of Doubt 焚毀疑寨; Steadfast Endurance of Humiliation 堅韌受辱; Praying to Resist Temptation 祈禱拒惑; A Letter from the Heavenly City 天城來信; The Female Disciple Departs the World 女徒辭世.

In such vernacular Christian novels, there were no chapter titles; the aforementioned headings actually served as captions for the illustrations, functioning to divide the text into sections. The content of the images corresponded to episodic stories, with each illustration capturing the climax of a segment, collectively forming a narrative chain of the Christian’s suffering, deliverance, and enlightenment, all thematically serving the doctrinal tenets of the Bible. In terms of narrative style, this approach closely resembled the literary model of late Qing “Sacred Edict” preaching novels, where multiple short stories revolved around the theme of the emperor’s sacred instructions. The illustrations, acting as titles for the novel’s episodic stories, mimicked the thematic form of “Sacred Edict” preaching in both their naming and content relationship. Each title in the novel’s illustrations symbolized a story segment and embodied the ethical themes of “loyalty and filial piety”, “good and evil”, “chastity and licentiousness”, and “fortune and misfortune” found in the

Sacred Edict. In other words, the missionaries, in writing

The Pilgrim’s Progress series and the illustrations for

The Spiritual Warfare in Vernacular, cleverly borrowed the vocabulary and framework of mainstream Chinese ethics while infusing them with the core Christian concept of personal salvation. For example, the missionaries imitated and transformed the Confucian notions of “loyalty and filial piety”. Illustrations such as “Remaining Loyal unto Death” and “Approaching the Heavenly City” in

The Pilgrim’s Progress in Vernacular emphasized the Christian’s absolute loyalty to the “Heavenly City’s Monarch (God)”. The depiction of the Christian’s entire journey to the Heavenly City in the illustrations was a response to the call of the Monarch, aligning with the Confucian core concept of “loyalty” to the ruler. In the visual narrative, titles often referenced the “Heavenly Father”, and the protagonist’s actions aimed to ultimately return to the “Father’s home” (the Heavenly City), imitating the Confucian ethical framework of “filial piety to the father”. However, in the specific use of images for preaching, the missionaries altered the core meanings of “loyalty” and “filial piety”. In Confucian thought, the primary focus of “loyalty” is allegiance to the earthly ruler and the dynasty, whereas the illustrations in

The Pilgrim’s Progress portrayed “loyalty” as directed toward a God who transcends worldly rulers. The narrative themes of images such as “Breaking Free from the Worldly Net”, “Gaining Freedom in the Land”, and “Approaching the Beautiful Mountain” in

The Pilgrim’s Progress in Vernacular conveyed that, “when God’s call conflicts with worldly opposition (e.g., family and neighbors in ‘Attempting to Halt the Journey’), Christians explicitly advocate loyalty to God” (

Z. Li 2012, p. 85). This shifted the object and ethical principle of Confucian loyalty. Similarly, the core meaning of “filial piety” was reinterpreted. In the

Sacred Edict, Confucian “filial piety” is the foremost virtue and the cornerstone of social ethics. However, in illustrations such as “Beginning the Heavenly Path” and “Approaching the Narrow Gate”, Christians abandon their wives and children and leave home—actions that, from a Confucian perspective, violate family ethics and represent extreme unfilial behavior within the patriarchal system. Yet, through the accompanying textual narrative, such behavior was portrayed as a greater form of “filial piety” toward the “Heavenly Father”, a “great love” aimed at saving the souls of family members. This essentially subverted the priority of “blood-related filial piety” in traditional patriarchal society, replacing it with “filial piety to the Heavenly Father” that transcends “earthly filial piety”. The missionaries used images to mimic the traditional

Sacred Edict but made fundamental changes to the core tenets of loyalty and filial piety. The same cultural acceptance strategy was applied to concepts such as “good and evil”, “chastity and licentiousness”, and “fortune and misfortune”. The illustrations borrowed familiar ethical vocabulary—loyalty, filial piety, goodness, evil, chastity, licentiousness, fortune, misfortune—closely associating them with the popular

Sacred Edict teachings. This not only lowered the barrier to cultural acceptance but also advanced the popular interpretation and dissemination of Christian doctrines.

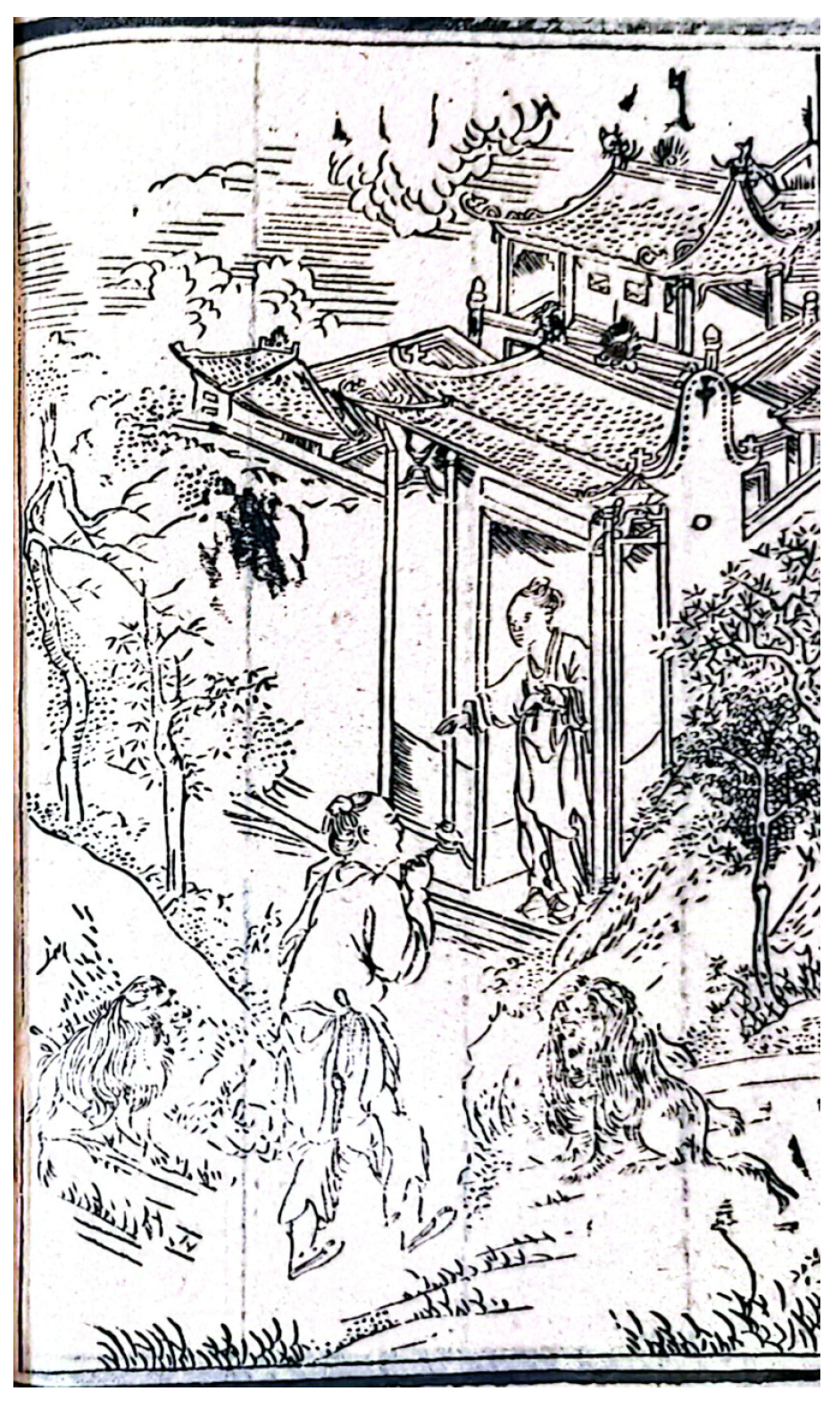

From the perspective of specific visual themes, the illustrations in Christian novels like

The Pilgrim’s Progress in Vernacular utilized the format of the

Sacred Edict to create intertextuality with the written content. The illustrators of missionary woodcut novel illustrations were typically anonymous local Chinese draftsmen and engravers. Under the guidance of the missionaries, they specifically created or thoroughly localized adaptations for the Chinese translations. These illustrations were not simple reproductions of Western originals but consciously embedded Christian narratives within a Chinese visual context (e.g., employing traditional line drawing techniques, Chinese architecture, and attire) to achieve cultural adaptation and dissemination. Scholar Lai Zipeng, in The Transfiguration of a Classic:

A Study on the Chinese Translation of The Pilgrim’s Progress in the Late Qing Dynasty (2012), points out that the “Sinification” of such illustrations was a key component of the missionaries’ “localized narrative strategy,” and their anonymity also reflects the obscured authorship in late Qing folk print production (

Z. Li 2012, p. 85). Therefore, the primary purpose of these illustrations was to promote the teachings of the Bible and encourage the public to convert to Christianity. For example, the first illustration in

The Pilgrim’s Progress in Vernacular, titled “Pointing to the Narrow Gate”, clearly conveys this missionary objective. The image depicts a preacher guiding a Christian to establish faith in Christ, while the accompanying verse elucidates the theme: “Fortunate are we to receive the gospel from saints, who show us the path from death to life.” This strategy of using “sacred instruction for evangelism” through imagery aligns with the pattern seen in late Qing Sacred Edict novels, which often began with moral exhortations. Similarly, the first illustration in

The Pilgrim’s Progress in Vernacular (Continued), titled “A Widow Instructing Her Children”, continues the story by portraying a Christian wife, under divine guidance, teaching her children to embark on a pilgrimage to heaven. “Instructing the Children in Her Husband’s Stead” relates to the Sacred Edict’s emphasis on marital harmony and a woman’s virtue in supporting her husband and educating their children. The illustration’s theme interweaves with the text—“earnestly imploring the Heavenly Father to bestow grace and lead us to Mount Zion”—to express the female Christian’s faith in following her husband’s path to pilgrimage (

Burns 1872, p. 8). The opening illustrations of both volumes of

The Pilgrim’s Progress reflect the traditional Chinese ethical teaching of “a wife following her husband”, while skillfully connecting the visual and textual themes with biblical teachings. In other words, while the

Sacred Edict promoted the Confucian ethics of “self-cultivation, family regulation, state governance, and world peace”, the missionaries’ illustrations in Christian novels emphasized how individuals should face God and seek salvation, focusing on personal redemption to advance the spread of Christian doctrine. The illustrations in works such as

The Pilgrim’s Progress,

The Spiritual Warfare in Vernacular, and

Gusu’s Journey were cloaked in the Confucian values of “loyalty, filial piety, chastity, and righteousness”, strategically integrating with popular culture. Although the core of the story—such as scenes of Christians leaving their families to embark on a heavenly journey—remained centered on devotion to God, the thematic focus, narrative ethics, character attire, and scene settings were deeply infused with local Chinese flavor.

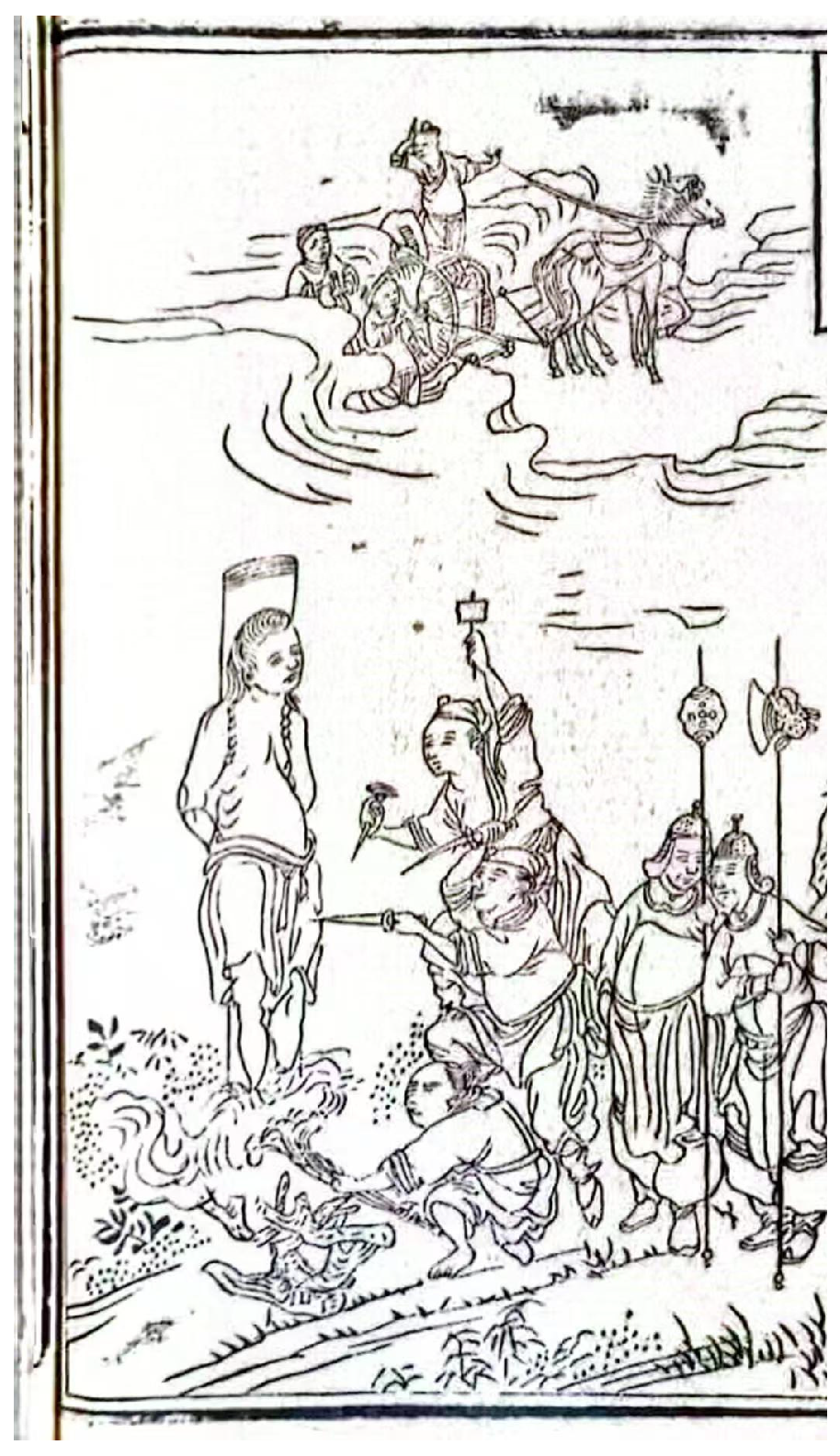

2.2. The Reception of Traditional Chinese Didactics Through Visual Imagery

The illustrations in Christian novels skillfully integrated China’s indigenous “didactic” educational system. When designing novel illustrations, missionaries cleverly incorporated “Confucian ethics”, “Buddhist causality”, and “Daoist imagery” endowing them with the significance of traditional Chinese-style “didacticism” and “moral instruction”. For example, illustrations such as “Observing Chickens to Discuss the Dao” and “Using Trees to Illustrate Human Nature” in The Pilgrim’s Progress in Vernacular (Continued) drew inspiration from the Confucian concept of “investigating things to extend knowledge” and the “analogical” tradition of the Book of Songs. The thematic focus of these images was to observe natural phenomena like chickens and trees to comprehend the greater truths of life. Didactic methods such as “discussing the Dao” and “illustrating humanity” were widely accepted forms of education among scholars and commoners alike. Furthermore, missionaries also incorporated Buddhist and Daoist concepts to convey warnings and teachings through imagery. The illustration “Displaying Corpses to Punish Evil” in The Pilgrim’s Progress in Vernacular (Continued) strongly reflects the concept of karmic retribution—“good begets good, evil begets evil”—which resonated deeply with the prevailing Buddhist and folk beliefs in society. The title of the image served as a verbal admonition, while its content depicted a “hell” scene from Buddhism, aiming to caution the audience. In illustrations such as “Approaching the Heavenly City” and “Welcoming into the Beautiful Palace”, missionaries portrayed imagery of a heavenly city and a magnificent palace, which easily evoked associations among the common people with Daoist beliefs of “immortal realms” and “Penglai”. This localized the abstract concept of a “foreign heaven” into a tangible and idealized Daoist afterlife. Within this didactic framework, missionaries did not directly challenge or replace indigenous moral principles but instead executed a subtle “transformation” or “symbiosis”. It is widely known that the official didactic text Sacred Edict (Shengyu Guangxun) was promulgated by the emperor. Local officials delivered its contents—covering topics such as filial piety, fortune and misfortune, and neighborly harmony—to the common people monthly during xiangyue (community covenant) ceremonies. This practice exemplified the imperial authority’s direct dissemination of moral education to the populace, a mechanism keenly observed and utilized by missionaries. The illustrations in The Pilgrim’s Progress in Vernacular series adopted widely relatable “preaching” and “teaching” scenarios, exhibiting ethical characteristics such as “explaining causality” and “ordering human relationships”. Although the ultimate goal was to propagate Christian teachings, the approach borrowed from the instructional model of the Sacred Edict. In other words, missionaries identified superficial connections between Christian doctrines and Chinese indigenous morals, leveraging the reading habits most familiar to the Chinese public to promote the acceptance of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in the local context. The illustrations in Christian novels like The Pilgrim’s Progress accurately targeted the local readership in Guangdong, integrating into China’s traditional didactic system and enhancing cultural affinity to facilitate the acceptance of Christian teachings. These illustrations were not standalone “foreign stories” from the Bible but rather “moral tales” infused with local ethics, indigenous didactic forms, and a localized path of spiritual practice. However, only when the core message of the story—“the faith in Jesus Christ redeems the toiling masses”—was revealed could Christian doctrines be widely propagated. By this point, the audience had already accepted the overarching narrative framework, psychologically reducing their resistance to Christian teachings. This demonstrates the success of missionary novels in adopting the illustrations of Chinese novels.