Composite Female Figurines and the Religion of Place: Figurines as Evidence of Commonality or Singularity in Iron IIB-C Southern Levantine Religion?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Pantheons in the Iron II Levant

3. A Religion of Place

4. Why Figurines Are a Good Fit

5. The Challenges

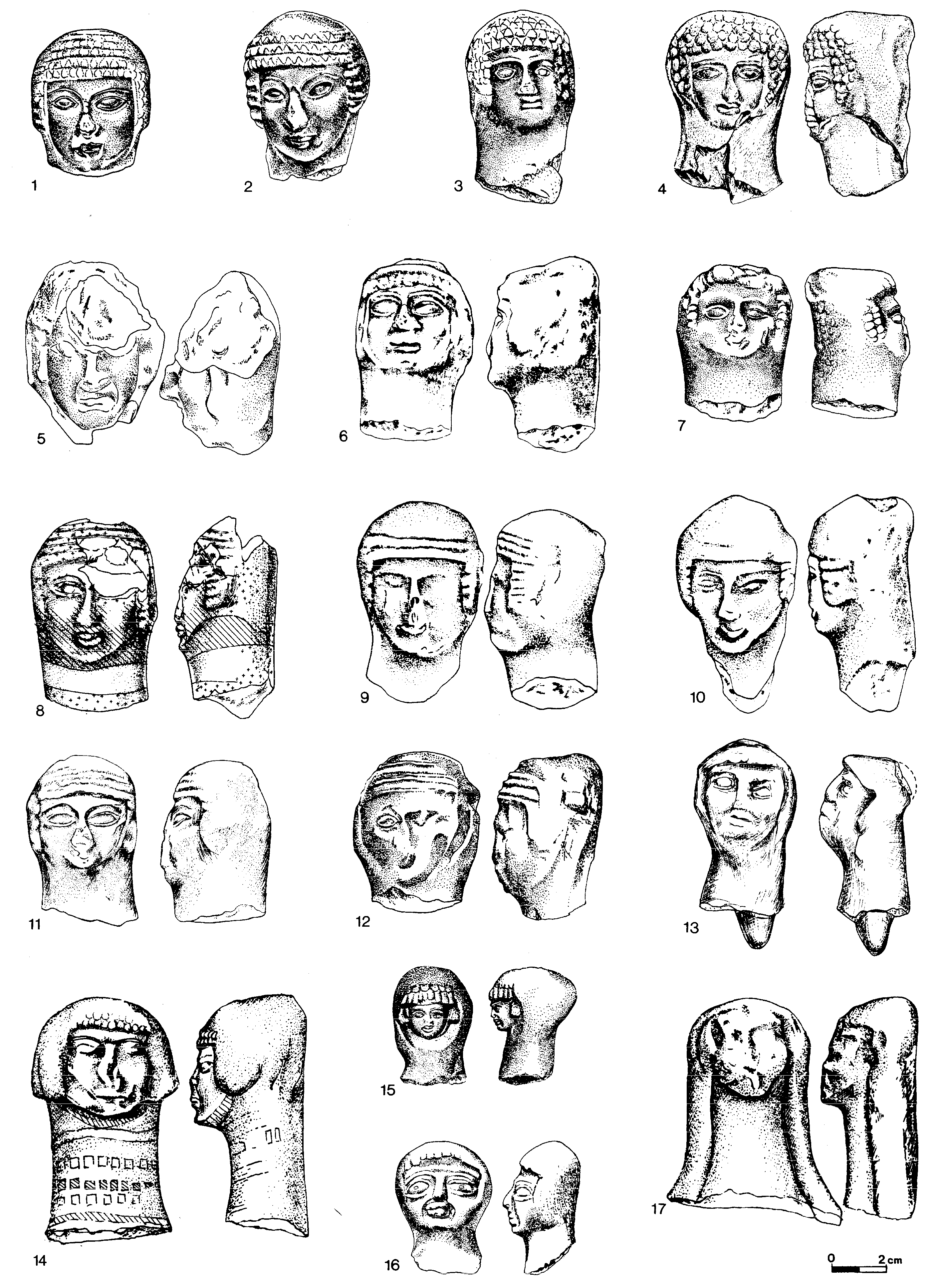

6. The Corpora

6.1. Judah

6.2. Philistia

6.3. Transjordan

6.4. Israel

6.5. Phoenicia and Cyprus

7. Discussion: Interpreting Coherence and Diversity

7.1. Iconographic Consistency and Variation

7.2. Technological Consistency and Variation

7.2.1. The Pillar Bases

7.2.2. The Molded Faces

7.3. Regional Correlations Between Molds, Pillar Styles, and Gestures?

7.4. Judahite Composite Females and Intersite Homogeneity

“In exorcistic incantations, doors, windows, thresholds, and other kinds of openings constitute a dangerous and liminal space between the inside and the outside of the house, between the private and the public place. Prone to drafts, these particular spaces are also perfect for the manifestations of demons. In ancient Mesopotamia, demons are noisy and some sounds may be identified as their main manifestation. The terrible cry ikkillu is likely to be understood as the demon-Clamor (of mourning), being a sign of the evil it represents, that is, death.”

7.5. Intensity and Production Organization

7.6. Geography Revisited

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Note that this petrographic study has some drawbacks. Only twenty pieces were examined. Out of 186 likely JPF fragments identified at the site (Ben-Shlomo and McCormick 2021, p. 27), only thirteen JPF fragments were tested (ca. 7% of JPF corpus at the site), divided among body fragments, pinched heads, and molded heads. This could be compared with 120 figurines in the Jerusalem provenience study (including 56 anthropomorphic fragments, the vast majority of which are clearly JPF types; Darby 2014, pp. 183–212; Ben-Shlomo and Darby 2014). To demonstrate the importance of sample size, this larger Jerusalem study overturned conclusions based on a previous 15-sample petrographic study and an 18-sample INAA study of the same corpus of City of David specimens (Goren et al. 1996; Yellin 1996). These previous studies concluded that almost all of the figurines in Jerusalem were made from the same clay that characterized regular Jerusalem pottery, while the larger study demonstrated that terra rossa only represented slightly more than 20% of the figurines tested. The vast majority were made from clay never used to produce Jerusalemite pottery. In the Nasbeh study, all but one of the JPFs in the tested corpus (ca. 12 of 13 fragments) were sourced as rendzina clay, attributed to the Jerusalem area, as were three chair/bed models, one flat-backed molded head, and one pinched head with beard (Ben-Shlomo and McCormick 2021, p. 34, Table 1). Of the probable composite JPFs, the study tested one likely JPF molded head (ibid., Fig. 4:6) and three clear JPF molded heads (ibid., Figs. 4:3, 8, 15), all typed as rendzina clay, as well as one body (pillar + torso) (ibid., Fig. 4:5) typed as rendzina and two torsos (ibid., Fig. 4:1, 12), one of which was typed as terra rossa clay (ibid., Fig. 4:1) and the other rendzina (ibid., Fig. 4:12). Bodies could either have had a composite head or a pinched head (meaning they may not be relevant for the current analysis), but Fig. 4:1 might be more likely a composite figurine, since the body is hollow. As to the Jerusalem or Hill Country provenience, the authors note that rendzina clays are located ca. “10–25 km south-southeast of the site in the Jerusalem region” (ibid., p. 34) and are also located in the Shephelah and the Galilee. This pattern, while suggesting that tested figurines at Nasbeh were mostly made from different clays than those used for pottery at the site (ibid.), may or may not support the conclusion that the rendzina figurines were imported already constructed from the Jerusalem ceramics industry to Nasbeh (ibid., p. 36). Other explanations could include figurines coming from other rendizina clay sources and importing raw clay. Unfortunately, the archaeological context at Nasbeh makes it very difficult to assess the tested samples’ chronological or archaeological context, leaving open the possibility that the tested corpus is predominantly later from an eighth–sixth century horizon at a time when Jerusalem and Nasbeh (biblical Mizpah) have a more defined interrelationship (McCormick and Darby 2023). Of primary relevance here, the small tested JPF Nasbeh corpus may suggest only some amount of importing clay or completed figurines to the site rather than being emblematic of the entire corpus ranging across the Iron IIB-C. |

| 2 | Head no. 22 is discussed below. Note that no. 21 came from an open area that may be the extension of the Tel Reḥov shrine courtyard. Locus 1653, like its continuation, Locus 1647, accumulated to a considerable depth (ca. 0.60 m) gradually over the tenth and ninth centuries (Mazar 2020a, p. 297). In addition to several daily use objects, these two accumulations produced several metal objects, figurine fragments (including in L 1653: Mazar 2020b, p. 602 molded figurine head likely attached to altar no. 7; Saarelainen and Kletter 2020, p. 549 composite head no. 21; ibid., p. 541 body of a plaque-style female drummer no. 6; ibid., p. 549 plaque figurine leg fragment no. 20; in L 1647: ibid., p. 554 bird figurine no. 70; ibid., p. 561 horn/ear fragment no. 48; ibid., p. 551 horse rider body no. 24), three zoomorphic vessel fragments, a seal impression, and altar fragments (Mazar and Panitz-Cohen 2020, pp. 321–22), though it is difficult to identify whether any of these broken objects were deposited at the same time, given the depth of the loci. At least in the case of Locus 1647, the excavator notes that many of the sherds and fragments of figurines might be the results of discarded refuse (Mazar 2020a, p. 293), drawing into question what their deposition might indicate about their original context (see also Saarelainen and Kletter 2020, p. 572). Additionally, the altar was found smashed in pieces and several of the components were missing, suggesting it, too, may have been in a refuse context (Mazar 2020a., p. 294; note here it is referred to as no. 5 in the catalog, but that is incorrect. In fact, it is Mazar 2020b, p. 591, no. 4). |

| 3 | In addition to the stratigraphic details of body fragments cited in Darby 2014, pp. 254–56, which questions the likelihood of tenth century dating but leaves open late ninth–early eighth century dates, Kletter (1996) lists two molded heads in early loci at Lachish (98.B.4 and 99.B.2.B). Both of these contexts are somewhat problematic. For the molded head 98.B.4., although the locus list assigns the fragments to Locus 94c (Aharoni 1975, p. 109) dated to Stratum VI (the Late Bronze), Zuckerman (2012, p. 32, n. 39) points out that this locus was originally excavated as one large square (Locus 94) and was only subsequently divided into phases (Locus 94 = Stratum III, 94a = Stratum IV; 94b = Stratum V; 94c = Stratum VI), meaning that the materials were likely originally mixed as well. This calls into question the early date of the figurine head. Moreover, Aharoni (1975, p. 16) himself refers to the same head (ibid., Pl. 12:3) as coming from Strata IV-III, or the ninth through eighth centuries. The other head, Kletter 1996, 99.B.2.B, came from an open area, Locus 41, never discussed in the stratigraphic report. The locus produced many different items, including a number of metal artifacts, but ultimately the ceramics of Stratum IV proved to be the least well-represented at the site, leaving the dates somewhat vague, with a possible end in the late ninth century (Aharoni 1975, p. 15). |

References

- Aharoni, Yohanan. 1975. Investigations at Lachish: The Sanctuary and the Residency (Lachish V). Publications of the Institute of Archaeology 4. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Spencer. 2015. The Splintered Divine: A Study of Ishtar, Baal, and Yahweh Divine Names and Divine Multiplicity in the Ancient Near East. Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Amr, Abdel-Jalil. 1980. A Study of the Clay Figurines and Zoomorphic Vessels of Trans-Jordan during the Iron Age, with Special Reference to Their Symbolism and Function. Ph.D. thesis, University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Averett, Erin Walcek. 2021. The Iron Age Terracotta Figurines from Cyprus. In Iron Age Terracotta Figurines from the Southern Levant in Context. Edited by Erin Darby and Izaak J. de Hulster. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 125. Leiden: Brill, pp. 292–332. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Pirhiya. 1995. Catalogue of Cult Objects and Study of the Iconography. In Ḥorvat Qitmit; An Edomite Shrine in the Biblical Negev. Edited by Itzhaq Beith-Arieh. Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology 11; Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University, pp. 27–197. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arieh, Sara. 2011. Temple Furniture from a Favissa at ‘En Hazeva. Atiqot 68: 107–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo, David. 2021. Iron Age Figurines from Philistia. In Iron Age Terracotta Figurines from the Southern Levant in Context. Edited by Erin Darby and Izaak J. de Hulster. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 125. Leiden: Brill, pp. 119–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo, David, and Erin Darby. 2014. A Study of the Production of Iron Age Clay Figurines from Jerusalem. Tel Aviv 41: 180–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shlomo, David, and Amir Gorzalczany. 2010. Petrographic Analysis. In Yavneh I: The Excavation of the ‘Temple Hill’ Repository Pit and the Cult Stands. Edited by Raz Kletter, Irit Kiffer and Wolfgang Zwickel. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis Series Archaeologica 30. Fribourg: Academic Press, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 148–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo, David, and Lauren K. McCormick. 2021. Judean Pillar Figurines and ‘Bed Models’ from Tell en-Naṣbeh: Typology and Petrographic Analysis. Bulletin of the American Society of Overseas Research 386: 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shlomo, David, Ron Gardiner, and Gus van Beeck. 2014. Ceramic Figurines and Figurative Terra-cottas. In Excavations at Tell Jemmeh, Israel, 1970–1990. Edited by David Ben-Shlomo and Gus van Beeck. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology 50. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, pp. 804–27. [Google Scholar]

- Berlejung, Angelika. 2021. Divine Secrets and Human Imaginations: Studies on the History of Religion and Anthropology of the Ancient Near East and the Old Testament. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Briffa, Josef Mario. 2017. The Figural World of the Southern Levant during the Late Iron Age. Ph.D. thesis, University College London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Caubet, Annie. 2021. A Technical Perspective on Some Iron Age Pillar Figurines from Cyprus and the Levant. In Iron Age Terracotta Figurines from the Southern Levant in Context. Edited by Erin Darby and Izaak J. de Hulster. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 125. Leiden: Brill, pp. 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius, Izak. 2004. The Many Faces of the Goddess: The Iconography of the Syro-Palestinian Goddesses Anat, Astarte, Qedeshet, and Asherah, c. 1500–1000 BC. Fribourg: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Darby, Erin. 2014. Interpreting Judean Pillar Figurines: Gender and Empire in Judean Apotropaic Ritual. Forschungen zum Alten Testament 2. Reihe 69. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Darby, Erin D., and Izaak J. de Hulster, eds. 2021. Iron Age Terracotta Figurines from the Southern Levant in Context. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 125. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Daviau, P. M. Michèle. 2012. Diversity in the Cultic Setting: Temples and Shrines in Central Jordan and the Negev. In Temple Building and Temple Cult: Architecture and Cultic Paraphernalia of Temples in the Levant (2.-1. Mill. B.C.E.), Proceedings of a Conference on the Occasion of the 50th Anniversary of the Institute of Biblical Archaeology at the University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany, 28–30 May 2010. Edited by Jens Kamlah. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 435–58. [Google Scholar]

- Daviau, P. M. Michèle. 2014. The Coroplastics of Transjordan: Forming Techniques and Iconographic Traditions in the Iron Age. In ‘Figuring Out’ the Figurines of the Ancient Near East. Edited by Stephanie Langin-Hooper. Occasional Papers in Coroplastic Studies 1. New York: Association of Coroplastic Studies, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Daviau, P. M. Michèle. 2017. A Wayside Shrine in Northern Moab: Excavations in Wadi ath-Thamad. Oxford: Oxbow. [Google Scholar]

- Daviau, P. M. Michèle. 2022. Cultural Multiplicity in Northern Moʼāb: Figurines and Statues from Khirbat al-Mudaynah on the Wādī ath-Thamad. In Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan XIV: Culture in Crisis. Amman: Department of Antiquities of Jordan, pp. 251–65. [Google Scholar]

- Fales, Frederick Mario. 2021. Veiling in Ancient Near Eastern Legal Contexts. In Headscarf and Veiling: Glimpses from Sumer to Islam. Edited by Roswitha Del Fabbro, Frederick Mario Fales and Hannes D. Galter. Venezia: Edizioni Ca’ Foscari, pp. 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay, Uri. 2015. Ancient Mesopotamian Cultic Whispering into the Ears. In Marbeh Ḥokmah: Studies in the Bible and the Ancient Near East in Loving Memory of Victor Avigdor Hurowitz. Edited by Shamir Yona, Edward L. Greenstein, Mayer I. Gruber, Peter Machinist and Shalom M. Paul. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 185–220. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay, Uri. 2023. Emotions and Emesal Laments. In The Routledge Handbook of Emotions in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Karen Sonik and Ulrike Steinert. New York: Routledge, pp. 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert-Peretz, Diana. 1996. Ceramic Figurines, Appendix A Catalogue. In Excavations at the City of David, 1978–1985: Directed by Yigal Shiloh: Volume 4: Various Reports. Edited by Donald T. Ariel and Alon de Groot. Qedem 35. Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem, pp. 29–84, 112–34. [Google Scholar]

- Goren, Yuval, Elisheva Kamaiski, and Raz Kletter. 1996. The Technology and Provenance of the Figurines from the City of David: Petrographic Analysis. In Excavations at the City of David, 1978–1985: Directed by Yigal Shiloh: Volume 4: Various Reports. Edited by Donald T. Ariel and Alon De Groot. Qedem 35. Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem, pp. 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gubel, Eric. 1991. From Amathus to Zarephath and Back Again. In Cypriote Terracottas: Proceedings of the First International Conference of Cypriote Studies, Brussles-Liege-Amsterdam, 29 May–1 June, 1989. Edited by Frieda Vandenabeele and Robert Laffineur. Brussels-Liège: A.G. Leventis Foundation, Vrije Universiteit Brussel-Université de Liège, pp. 131–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gunneweg, Jan, and Marta Balla. 2017. The Provenance of Anthropomorphic Statues, Figurines, and Pottery. In A Wayside Shrine in Northern Moab: Excavations in Wadi ath-Thamad. Edited by P. M. Michèle Daviau. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 201–3. [Google Scholar]

- Handy, Lowell K. 1994. Among the Host of Heaven: The Syro-Palestinian Pantheon as Bureaucracy. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, Tom A. 1975. A Typological and Archaeological Study of Human and Animal Representations in the Plastic Art of Palestine. Ph.D. thesis, Oxford University, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Hundley, Michael. 2013. Here a God, There a God: An Examination of the Divine in Ancient Mesopotamia. Altorientalische Forschungen 40: 68–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundley, Michael. 2022. Yahweh among the Gods: The Divine in Genesis, Exodus, and the Ancient Near East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hunziker-Rodewald, Regine. 2021. Molds and Mold-Links: A View on the Female Terracotta Figurines from Iron Age II Transjordan. In Iron Age Terracotta Figurines in the Southern Levant. Edited by Erin D. Darby and Izaak J. de Hulster. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 125. Leiden: Brill, pp. 220–55. [Google Scholar]

- Karageorghis, Vassos. 1991. The Coroplastic Art of Cyprus: An Introduction. In Cypriote Terracottas Proceedings of the First International Conference of Cypriote Studies, Brussels-Liège-Amsterdam, 29 May–1 June 1989. Edited by Frieda Vandenabeele and Robert Laffineur. Brussels-Liège: A.G. Leventis Foundation, Vrije Universiteit Brussel-Université de Liège, pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kletter, Raz. 1996. The Judean Pillar-Figurines and the Archaeology of Asherah. British Archaeological Reports 636. Oxford: Tempus Reparatum. [Google Scholar]

- Kletter, Raz. 1999a. Clay Figurines: Human and Animal Clay Figurines. In Tel ‘Ira: A Stronghold in the Biblical Negev. Edited by Itzhaq Beit-Arieh. Tel Aviv University Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology Monograph Series 15. Tel Aviv: The Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, pp. 374–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kletter, Raz. 1999b. Pots and Polities: Material Remains of Late Iron Age Judah in Relation to Its Political Borders. Bulletin of the American Society of Overseas Research 314: 19–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kletter, Raz. 2015. Iron Age Figurines. In Tel Malḥata: A Central City in the Biblical Negev. Edited by Itzhaq Beit-Arieh and Liora Freud. Vol. 2. Tel Aviv University Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology Monograph Series 32. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, Vol. 2, pp. 545–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kletter, Raz, and Katri Saarelainen. 2022. The Iron Age II Figurines and Zoomorphic Vessels of Tel Reḥov. Near Eastern Archaeology 85: 152–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Létourneau, Anne, Ellen De Doncker, and Olivier Roy-Turgeon. 2022. A Parade of Adornments (Isa 3:18–23): Daughters Zion in the Light of Gender and Material Culture Studies. Open Theology 8: 445–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markoe, Glenn E. 2000. Phoenicians. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, Amihai. 2020a. Area E: Stratigraphy and Architecture. In Tel Reḥov: A Bronze and Iron Age City in the Beth-Shean Valley Volume III: The Lower Mound: Area D. Edited by Amihai Mazar and Nava Panitz-Cohen. Qedem 61. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, pp. 261–326. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, Amihai. 2020b. Iron Age II Cult Objects . In Tel Reḥov: A Bronze and Iron Age city in the Beth-Shean Valley Volume IV: Pottery Studies, Inscriptions and Figurative Art. Edited by Amihai Mazar and Nava Panitz-Cohen. Qedem 62. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, pp. 583–638. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, Amihai, and Nava Panitz-Cohen, eds. Tel Reḥov, A Bronze and Iron Age City in the Beth-Shean Valley Volume III, The Lower Mound: Areas D, E, F and G. Qedem 63. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- McCormick, Lauren K. 2023. My Eyes Are Up Here: Guardian Iconography of the Judean Pillar Figurine. PhD thesis, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, Lauren K., and Erin Darby. 2023 Trade, Workshop, or Migration? Using Petrography to Assess Inter-site Connection. Presentation at the Annual Meeting of the American Institute of Archaeology, Chicago, IL, USA, January 4–7.

- Nakhai, Beth Alpert. 2015. Where to Worship? Religion in Iron II Israel and Judah. In Defining the Sacred: Approaches to the Archaeology of Religion in the Near East. Edited by Nicola Laneri. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Nunn, Astrid. 2021. Anthropomorphic Figurines from Iron II Phoenicia. In Iron Age Terracotta Figurines from the Southern Levant in Context. Edited by Erin Darby and Izaak J. de Hulster. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 125. Leiden: Brill, pp. 66–118. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, Elizabeth, Peter Hopkins, and Lily Kong. 2013. Introduction: Religion and Place—Landscape, Politics, and Piety. In Religion and Place: Landscape, Politics, and Piety. Edited by Peter Hopkins, Lily Kong and Elizabeth Olson. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornan, Tallay. 2009. In the Likeness of Man: Reflections on the Anthropocentric Perception of the Divine in Mesopotamian Art. In What is a God? Anthropomorphic and Non-Anthropomorphic Aspects of Deity in Ancient Mesopotamia. Edited by Barbara Nevling Porter. Transactions of the Casco Bay Assyriological Institute 2. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 93–151. [Google Scholar]

- Panitz-Cohen, Nava, and Amihai Mazar. 2020. Area C: Stratigraphy and Architecture. In Tel Reḥov: A Bronze and Iron Age City in the Beth-Shean Valley Volume II: The Lower Mound: Area C and the Apiary.;Qedem 60. Edited by Amihai Mazar and Nava Panitz-Cohen. Qedem 60. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, pp. 1–264. [Google Scholar]

- Pardee, Dennis. 1988. An Evaluation of the Proper Names from Ebla from a West Semitic Perspective: Pantheon Distribution According to Genre. In Eblaite Personal Names and Semitic Name-Giving: Papers of a Symposium in Rome July 15–17, 1985. Edited by Alfonso Archi. Archivi Reali di Ebla Studi I. Rome: Missione Archaeologica Italiana in Siria, pp. 119–51. [Google Scholar]

- Patai, Raphael. 1967. The Hebrew Goddess. New York: Ktav. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, Sarit. 2007. Drums, Women, and Goddesses: Drumming and Gender in Iron Age II Israel. Fribourg: Academic Press. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson-Solimany, Marie, and Raz Kletter. 2009. The Iron Age Clay Figurines and a Possible Scale Weight. In Salvage Excavations at Tel Moza: The Bronze and Iron Age Settlements and Later Occupations. Edited by Zvi Greenhut, Alon de Groot and Eldad Barzilay. Israel Antiquities Authority Reports 39. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, pp. 115–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pogratz-Leisten, Beate. 2022. Emotions and Religion: Ritual Performance in Mesopotamia. In The Routledge Handbook of Emotions in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Karen Sonik and Ulrike Steinert. New York: Routledge, pp. 425–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pongratz-Leisten, Beate. 2011. Divine Agency and Astralization of the Gods in Ancient Mesopotamia. In Reconsidering the Concept of Revolutionary Monotheism. Edited by Beate Pongratz-Leisten. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 137–87. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Barbara Nevling. 2000. The Anxiety of Multiplicity: Concepts of Divinity as One and Many in Ancient Assyria. In One God or Many? Concepts of Divinity in the Ancient World. Edited by Barbara N. Porter. Transactions of the Casco Bay Assyriological Institute. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 211–71. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Barbara Nevling. 2009. Introduction. In What is a God?: Anthropomorphic and Non-anthropomorphic Aspects of Deity in Ancient Mesopotamia. Edited by Barbara N. Porter. Transactions of the Casco Bay Assyriological Institute 2. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Press, Michael David. 2012. Ashkelon 4: The Iron Age Figurines of Ashkelon and Philistia. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, James B. 1943. Palestinian Figurines in Relation to Certain Goddesses Known Through Literature. American Oriental Series 24. New Haven: American Oriental Society. [Google Scholar]

- Pruss, Alexander. Iron Age Figurines from Syria. In Iron Age Terracotta Figurines from the Southern Levant in Context. Edited by Erin Darby and Izaak J. de Hulster. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 125. Leiden: Brill, pp. 333–74.

- Rendu Louisel, Anne-Caroline. 2016. When Gods Speak to Men: Reading House, Street, and Divination from Sound in Ancient Mesopotamia (1st millenium BC). Journal of Near Eastern Studies 75: 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüpke, Jörg, and Emiliano Rubens Urciuoli. 2023. Urban Religion beyond the City: Theory and Practice of a Specific Constellation of Religious Geography-making. Religion 53: 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarelainen, Katri, and Raz Kletter. 2020. Iron Age II Clay Figurines and Zoomorphic Vessels. In Tel Reḥov: A Bronze and Iron Age City in the Beth-Shean Valley Volume IV: Pottery Studies, Inscriptions and Figurative Art. Edited by Amihai Mazar and Nava Panitz-Cohen. Qedem 62. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, pp. 537–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, Seth. 2015. When the Personal Became Political: An Onomastic Perspective on The Rise of Yahwism. Hebrew Bible and Ancient Israel 4: 78–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurlock, JoAnne. 2006. Magico-Medical Means of Treating Ghost-Induced Illnesses in Ancient Mesopotamia. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Selz, Gebhard J. 1997. ‘The Holy Drum, the Spear, and the Harp’: Towards an Understanding of the Problems of Deification in Third Millennium Mesopotamia. In Sumerian Gods and their Representations. Edited by Irving L. Finkel and Markham J. Geller. Cuneiform Monographs 7. Groningen: Styx, pp. 167–209. [Google Scholar]

- Shehata, Dahlia. 2023. Emotions and Musical Performance. In The Routledge Handbook of Emotions in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Karen Sonik and Ulrike Steinert. New York: Routledge, pp. 246–68. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Jonathan Z. 1978. Map Is Not Territory. In Map Is Not Territory: Studies in the History of Religion. Leiden: Brill, pp. 289–310. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Mark S. 2010. God in Translation: Deities in Cross-Cultural Discourse in the Biblical World. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, Margreet L., and P. M. Michèle Daviau. 2024. Field A: The Domestic Complex and Temple Building. In The Iron Age Town of Mudayna Thamad, Jordan: Excavations of the Fortifications and Northern Sector (1995–2012). Edited by Robert Chadwick, P. M. Michèle Daviau, Magreet L. Steiner and Margaret A. Judd. Bar International Series 3193. Oxford: BAR Publishing, pp. 109–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tassie, Geoffrey J. 2009. Hairstyles Represented on the Salakhana Stelae. In The Salakhana Trove: Votive Stelae and Other Objects from Asyut. Edited by Terrence DuQuesne. Oxfordshire Publications in Egyptology 7. London: Da’th Scholarly Services, Darengo Publications, pp. 459–536. [Google Scholar]

- Thareani, Yifat. 2011. The Finds. In Tell ‘Aroer: The Iron Age II Caravan Town and the Hellenistic-Early Roman Settlement: The Aviram Biran (1975–1982) and Rudolph Cohen (1975–1976) Excavations. Edited by Yifat Thareani. Annual of the Nelson Glueck School of Biblical Archaeology 8. Jerusalem: Hebrew Union College—Jewish Institute of Religion, pp. 115–300. [Google Scholar]

- Tufnell, Olga. 1953. Lachish 3 (Tell ed-Duweir): The Iron Age. Published for the Trustees of the late Sir Henry Wellcome by the Oxford University Press. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Toorn, Karel. 1995. The Significance of the Veil in the Ancient Near East. In Pomegranates and Golden Bells: Studies in Biblical, Jewish and Near Eastern Ritual, Law, and Literature in Honor of Jacob Milgrom. Edited by David P. Wright, David Noel Freedman and Avi Hurvitz. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 327–40. [Google Scholar]

- Werlen, Benno. 2021. World-Relations and the Production of Geographical Realities: On Space and Action, City and Urbanity. In Religion and Urbanity Online. Edited by Susanne Rau and Jörg Rüpke. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, Charlotte M. 2007. Complexity and Diversity in the Late Iron Age Southern Levant: The Investigations of ‘Edomite’ Archaeology and Scholarly Discourse. BAR International Series 1672. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggermann, Frans A. M. 2000. Lamaštu, Daughter of Anu: A Profile. In Birth in Babylonia and the Bible: Its Mediterranean Setting. Edited by Marten Stol and Frans A. M. Wiggermann. Leiden: Brill, pp. 217–49. [Google Scholar]

- Yellin, Joseph. 1996. Chemical Characterization of the City of David Figurines and Inferences about their Origin. In Excavations at the City of David, 1978–1985: Directed by Yigal Shiloh: Volume 4: Various Reports. Edited by Donald T. Ariel and Alon De Groot. Qedem 35. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, pp. 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, Alexander. 2012. A Reanalysis of the Iron Age IIA Cult Place at Lachish. Ancient Near Eastern Studies 49: 24–60. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Darby, E. Composite Female Figurines and the Religion of Place: Figurines as Evidence of Commonality or Singularity in Iron IIB-C Southern Levantine Religion? Religions 2025, 16, 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091181

Darby E. Composite Female Figurines and the Religion of Place: Figurines as Evidence of Commonality or Singularity in Iron IIB-C Southern Levantine Religion? Religions. 2025; 16(9):1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091181

Chicago/Turabian StyleDarby, Erin. 2025. "Composite Female Figurines and the Religion of Place: Figurines as Evidence of Commonality or Singularity in Iron IIB-C Southern Levantine Religion?" Religions 16, no. 9: 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091181

APA StyleDarby, E. (2025). Composite Female Figurines and the Religion of Place: Figurines as Evidence of Commonality or Singularity in Iron IIB-C Southern Levantine Religion? Religions, 16(9), 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091181