Texts, Architecture, and Ritual in the Iron II Levant

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Texts in Levantine Rituals

1.2. Ritual in the Archaeology of Performance

1.3. Reconstructing the Roles of Texts in Levantine Rituals

2. Texts in Northern Levantine Rituals

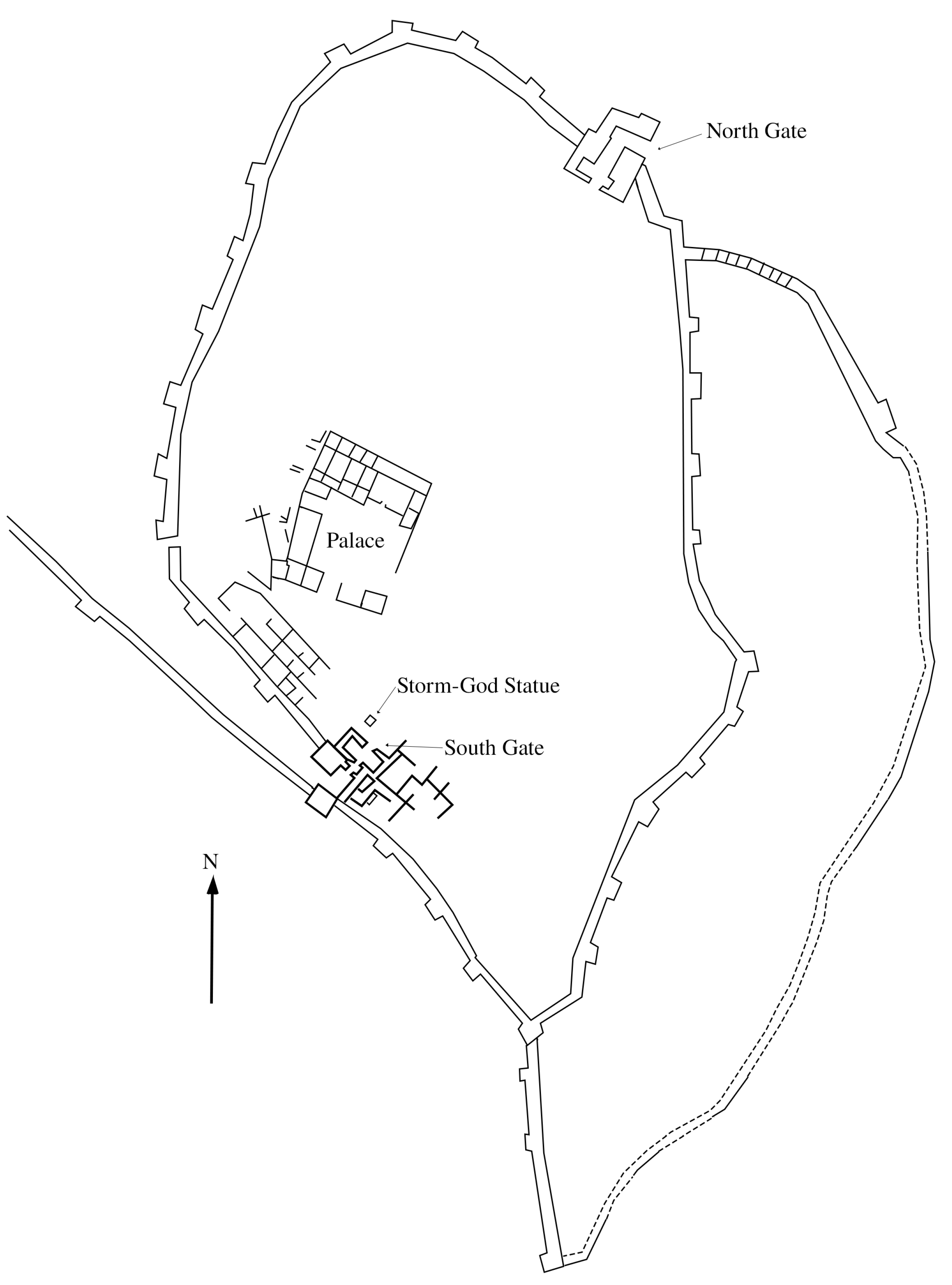

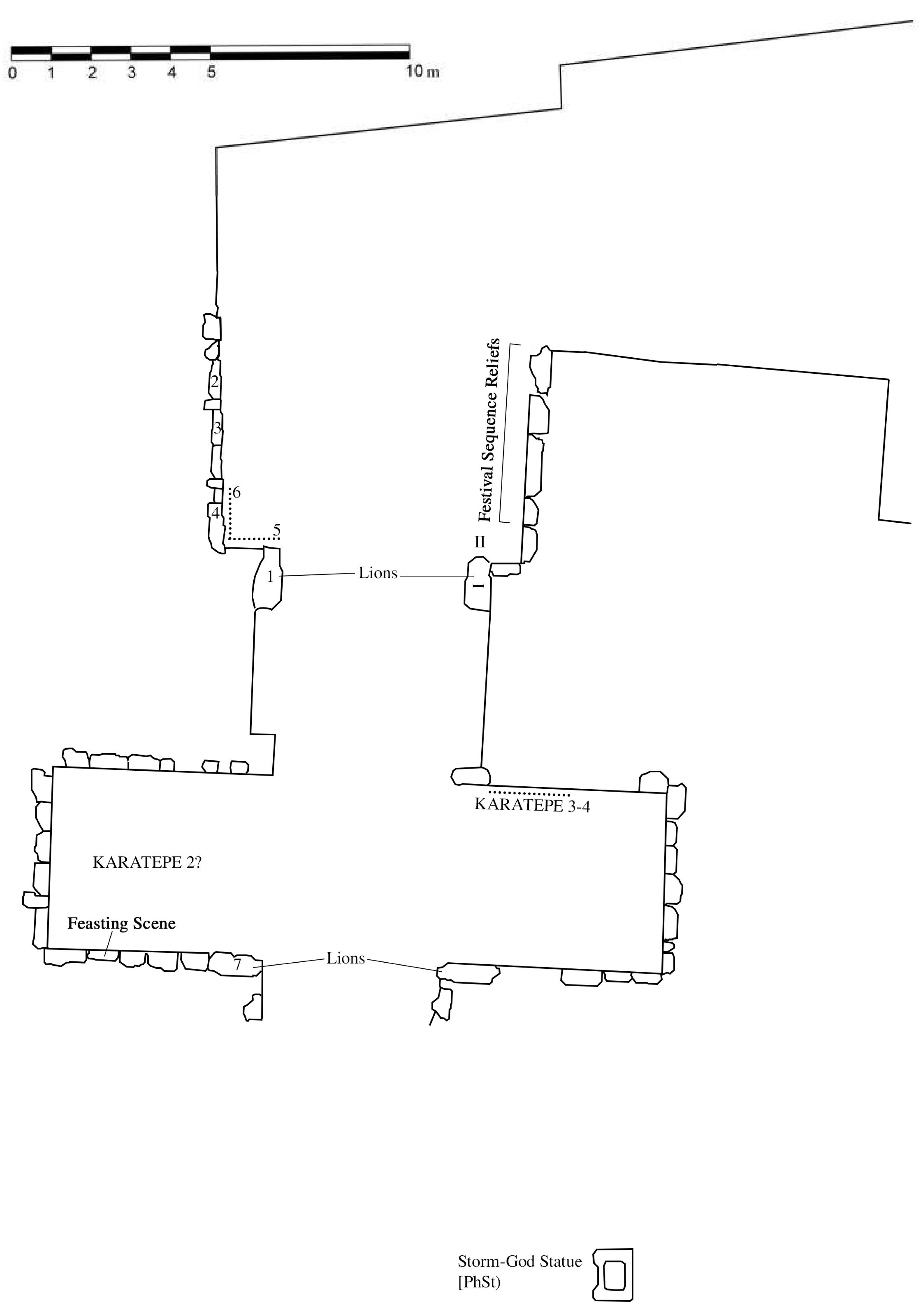

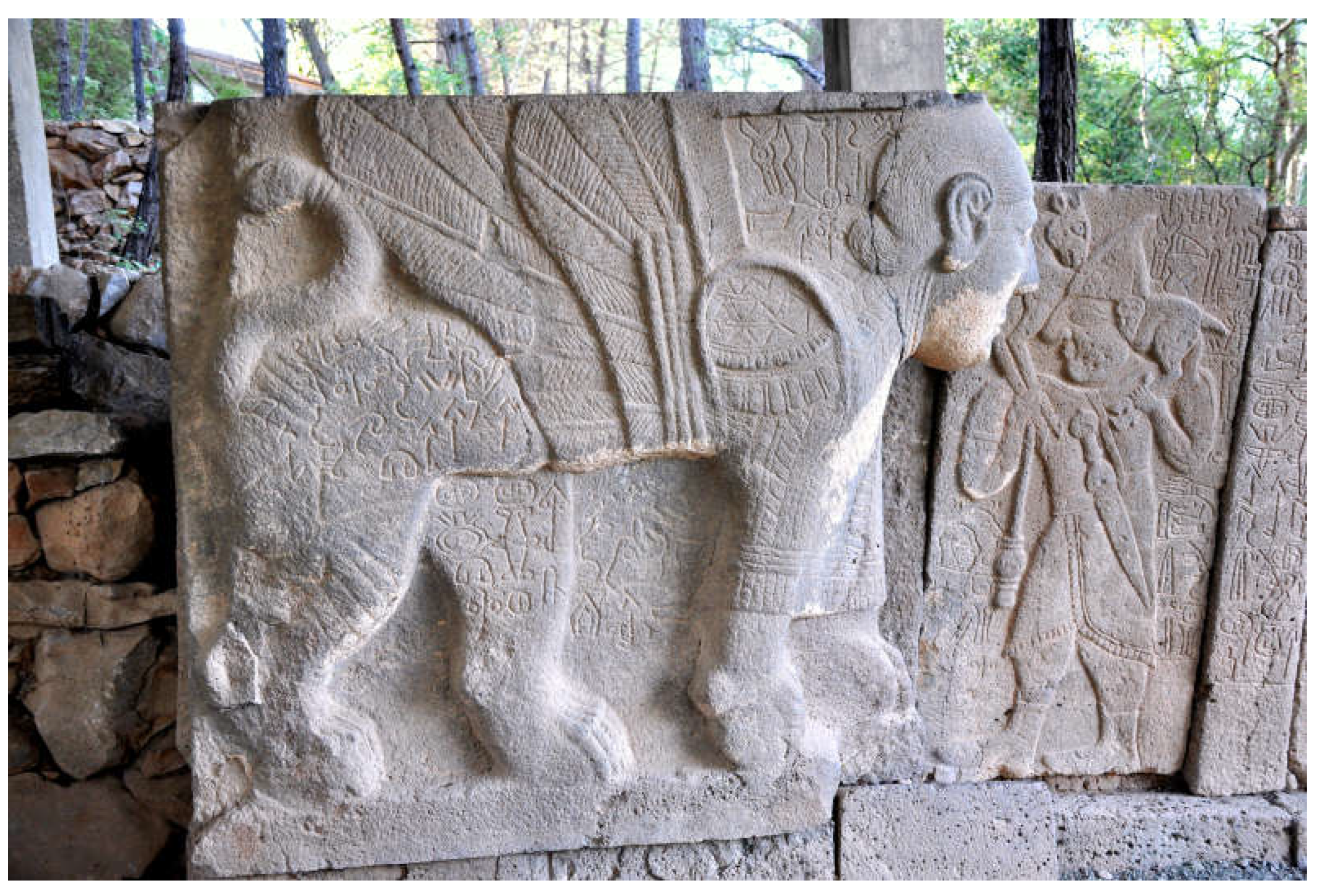

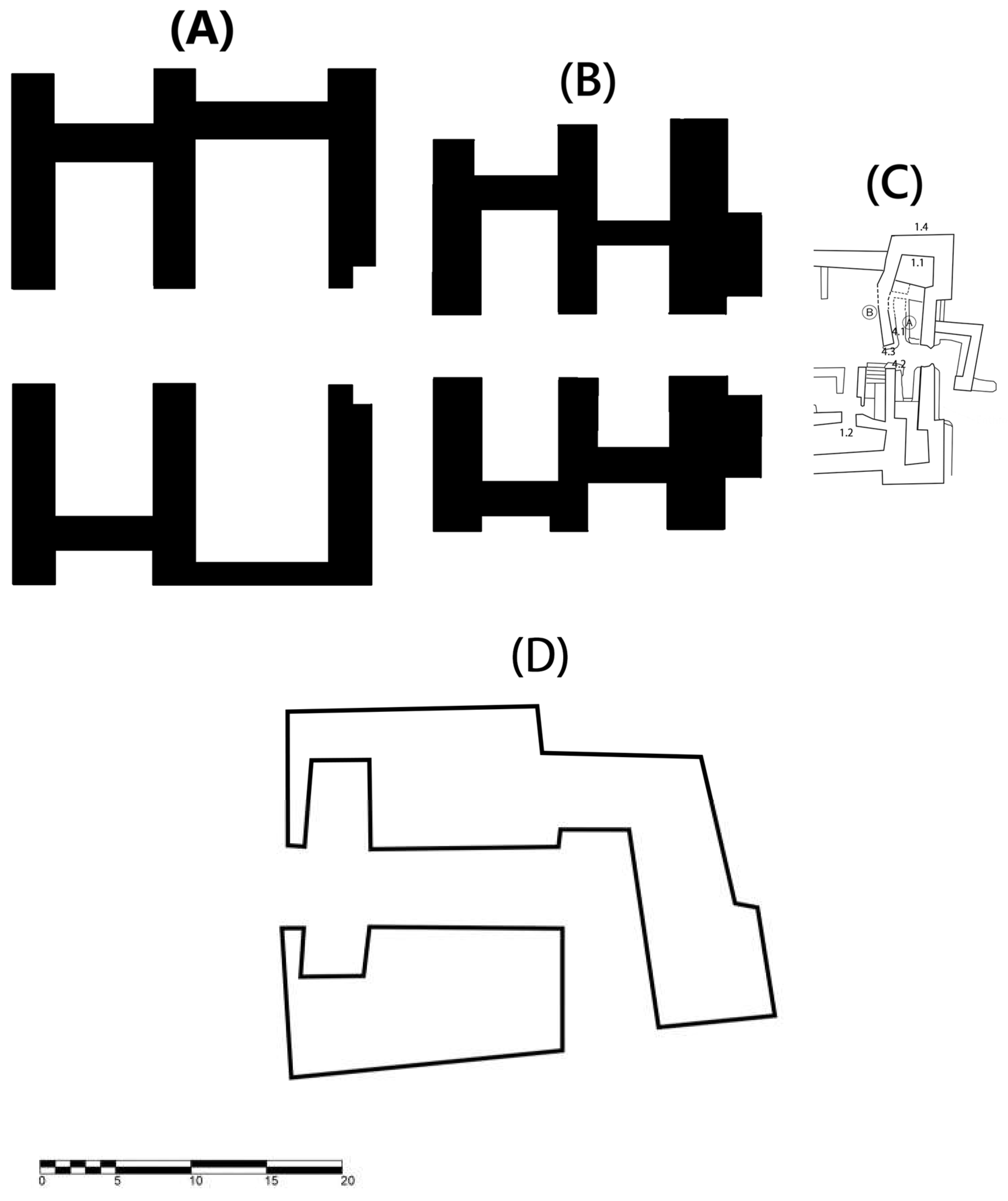

2.1. Karatepe-Aslantaş

wa/i-na |i-zi-sa-tu-na ta-ia (“FLUMEN”)há-pa + ra/i-sá |OMNIS-MI-i-sá |(ANNUS)u-si mara/i+ra/i BOS.ANIMA-sá (L.486)REL-tu-na-ha (OVIS.ANIMA)há-wa/i-sá |”VITIS”(-)há + ra/i-ha |OVIS.(ANIMA)-wa/i-sa

Ilya Yakubovich argues that the verb izzista- “to honor”that describes this triannual practice always occurs in cultic contexts and describes a specific ritual performance (Yakubovich 2020, pp. 470–71). This is confirmed by the Phoenician description of this ritual in Phu (KAI 26 A) II:19-III:2:“And every river-land will begin to honour him: by(?) the year an ox, and at the cutting(?) a sheep and at the vintage a sheep.”3

wylk zbḥ l kl hmskt zbḥ ymm ʾlp wb[ʿt ḥ]rš š wbʿt qṣr š

Here, the Luwian verb izzista- is translated by Phoenician ylk zbḥ “bring a sacrifice,” highlighting two elements of this ritual: travel and offering. These inscriptions thus prescribe a pilgrimage from the river-land to Azatiwataya.“and the whole district will bring him a sacrifice: the annual sacrifice is an ox, at the time of ploughing a sheep, and at the time of reaping a sheep.”4

|za-ia-pa-wa/i SCRIBA-la-li-ia IDEUS-ni-i-sa IDEUS-na-(OCULUS)a-za-mi-sa-ha |(“CAPERE + SCALPRUM”) REL-za-ta

This inscription draws attention to its own production in response to the assemblage in the south gate. The same may be true of a fragmentary Phoenician inscription found in the same context. Pho/S.I. a–b preserves personal names that do not occur in KARATEPE 1, suggesting that it was installed by someone other than Azatiwada (Çambel 1999, p. 35). Multiple elites thus engaged in this practice of erecting inscriptions alongside Azatiwada’s in the south gate.“These writings Masani and Masanazami incised.”

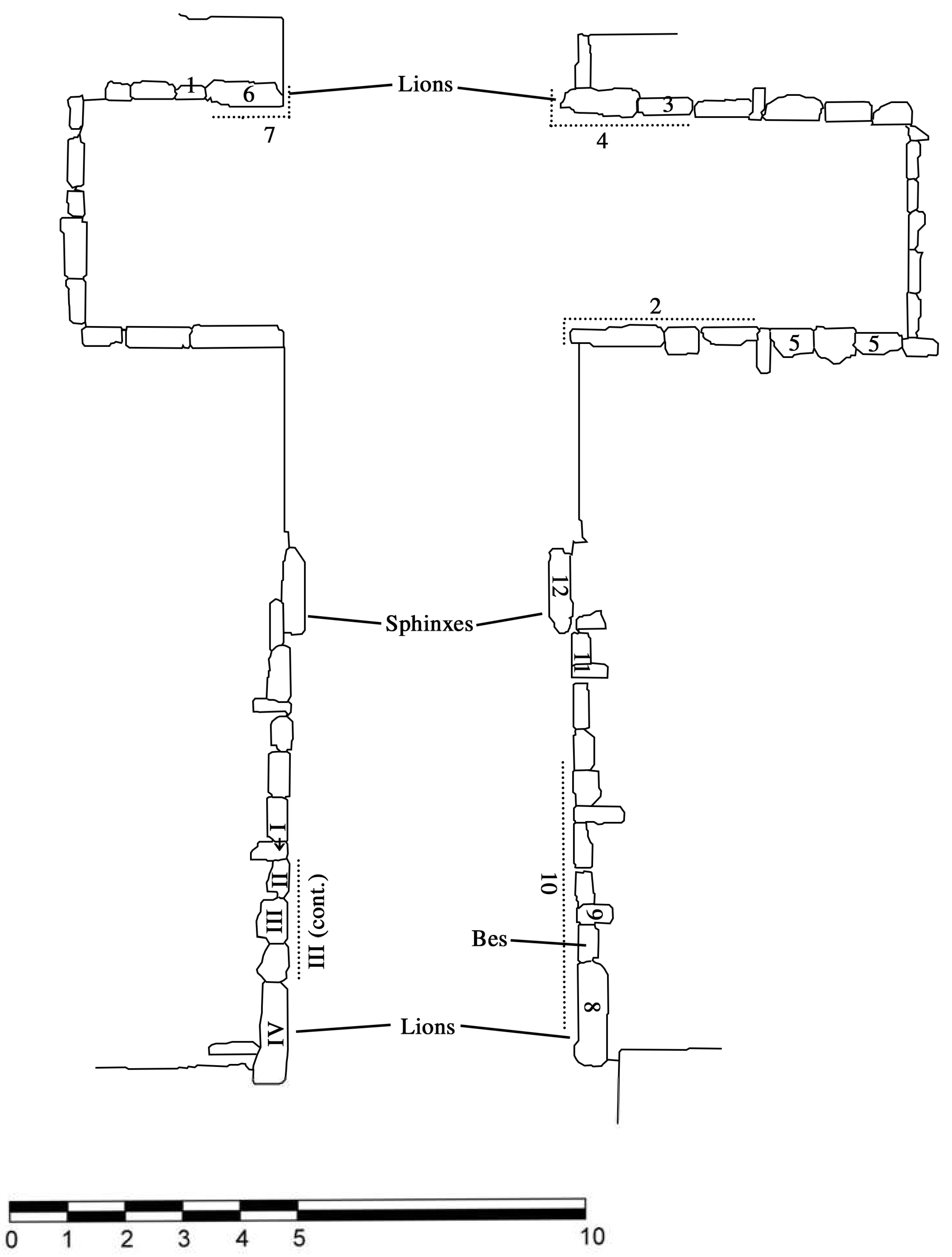

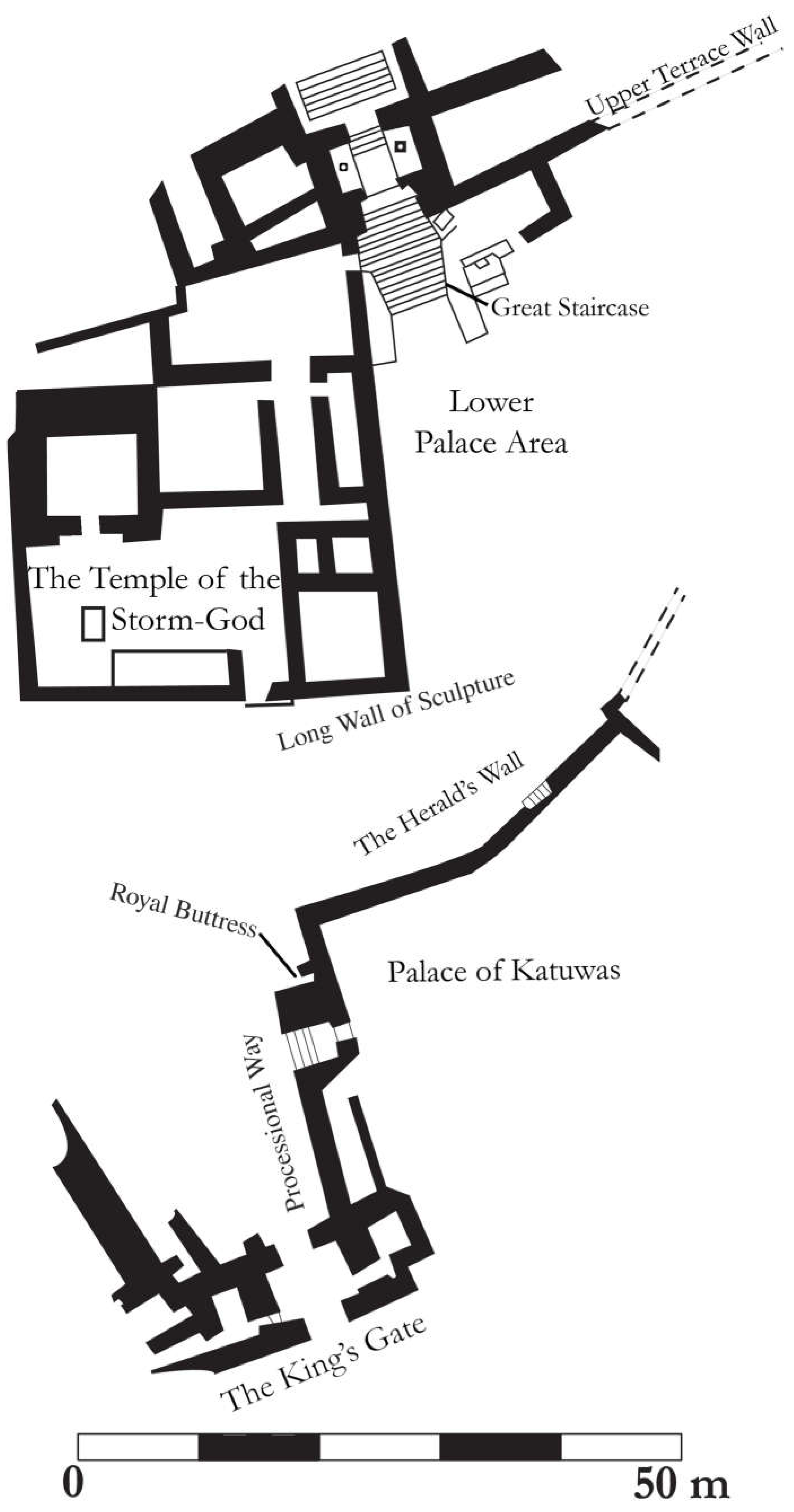

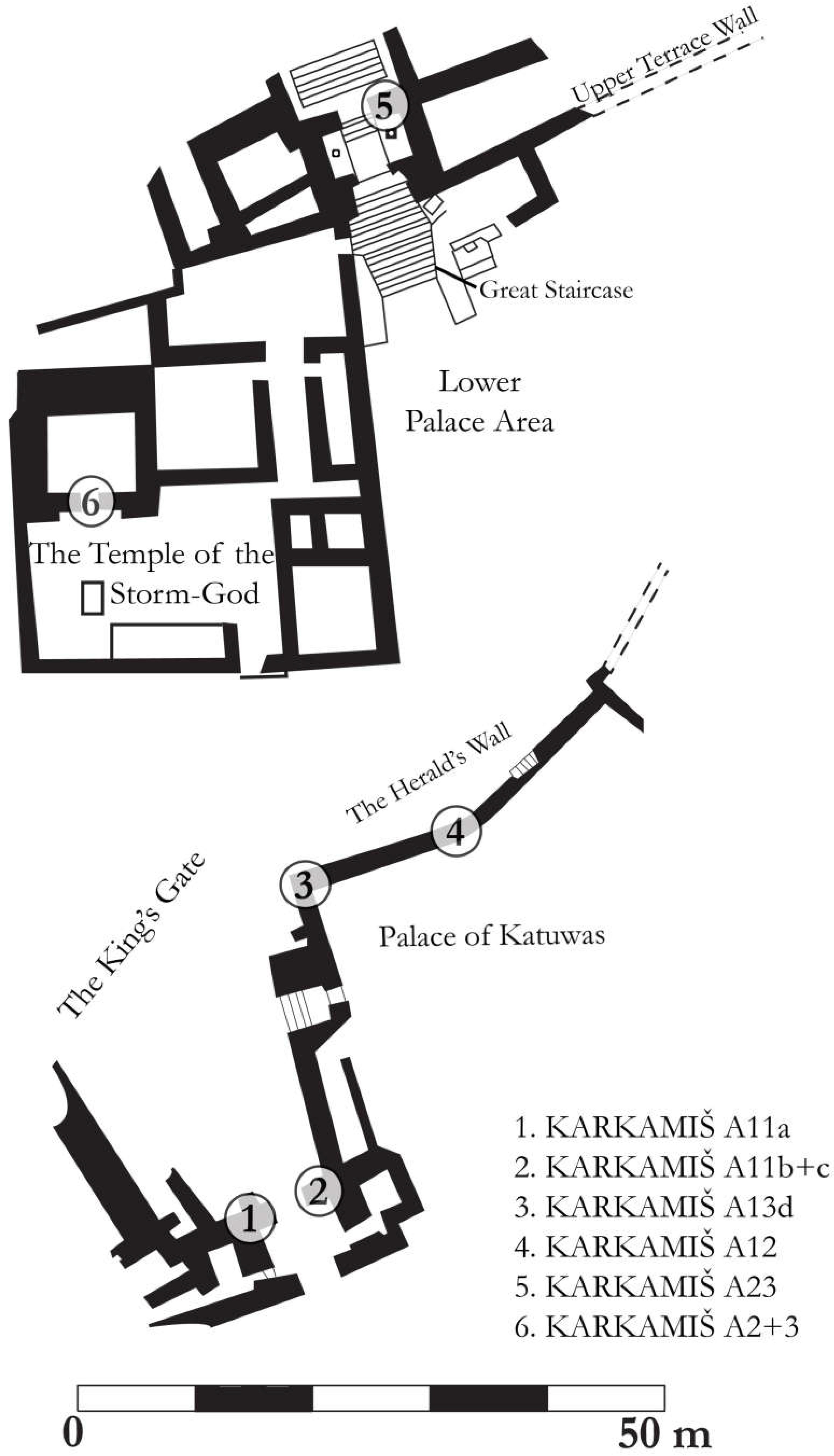

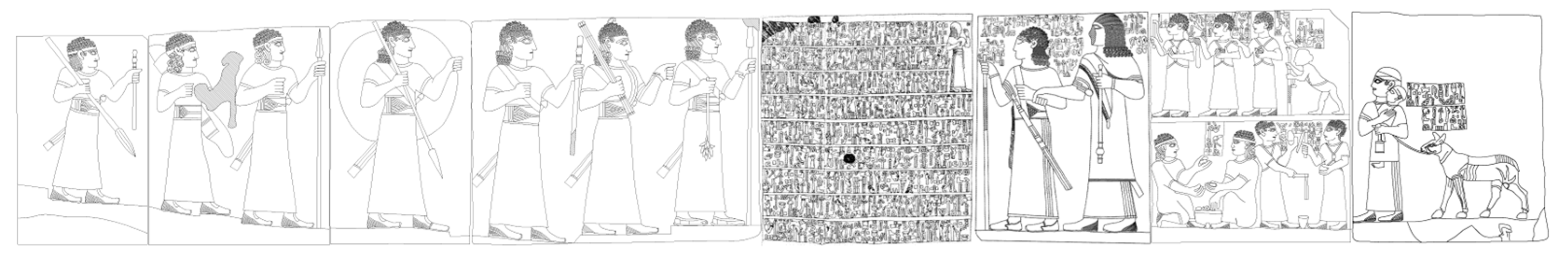

2.2. Karkemish

wa/i-da-*a |NEG2 |REL-a-ha |sa-ha-si

wa/i-da-*a mu-*a sa-ha-si

“You will(?) not SAHA it/them anything,

The rest of that inscription implies that this invocation was directed at the goddess Kubaba. While the verb in this invocation is uncertain, it and KARKAMIŠ A1b demonstrate that texts could function as ritual scripts at Karkemish.you will(?) SAHA it/them me.”7

|a-wa/i (LOQUI)ha + ra/i-nu-wa/i (DEUS)ku + AVIS-pa-pa-a

u-zu?-sa-wa/i-ma-ta-a (MANUS)i-sà-tara/i-i |MAGNUS + ra/i-nu-wa/i-ta-ni-i

I shall make speak: “O Kubaba,

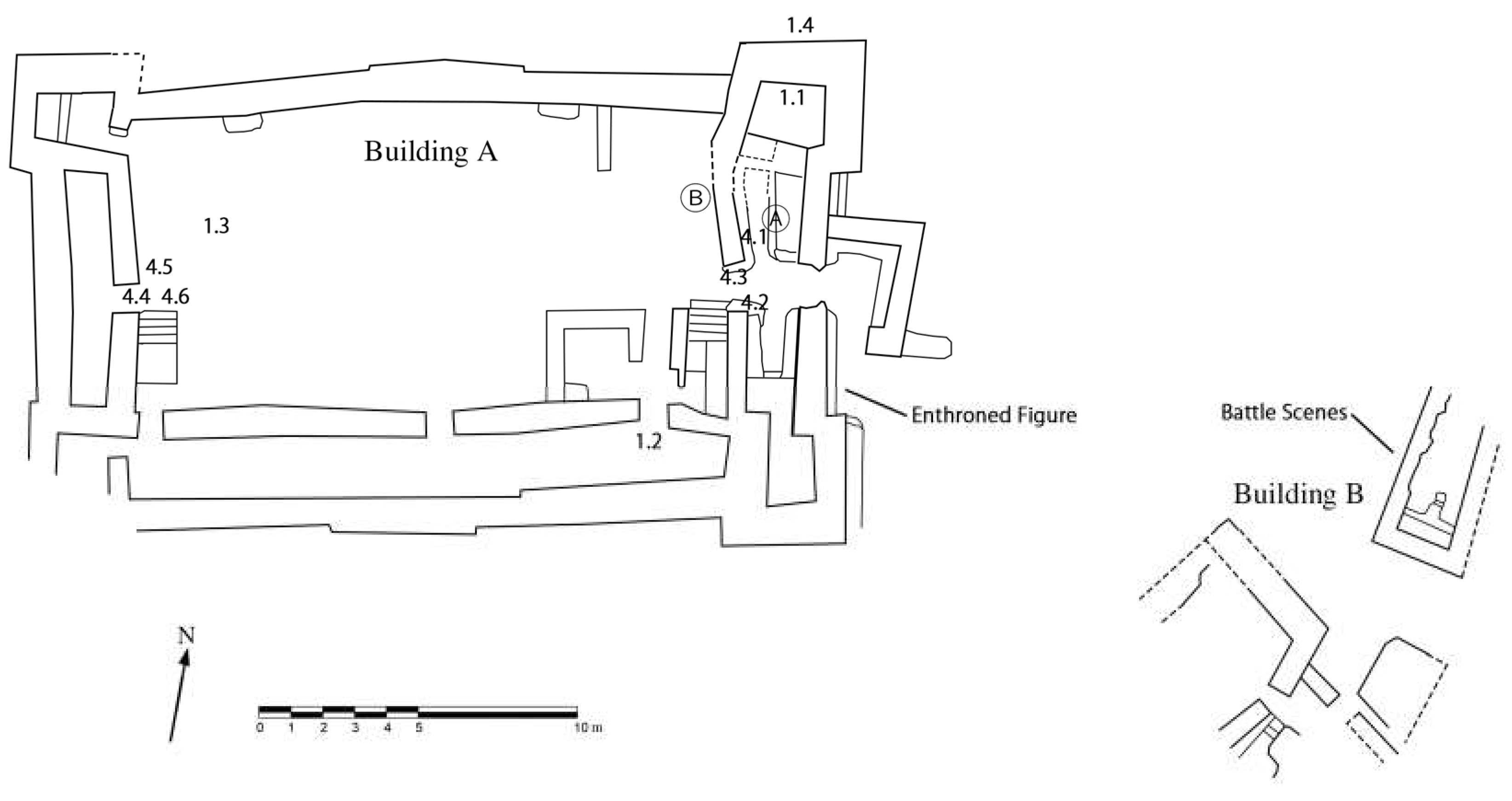

This is the only ritual action prescribed by this text. Yarrari’s text is focused on an act of reading. This action may be repeated given that Kamani is made to stand on the pedestal “three times and four times” in §19. This focus on the text is unprecedented at Karkemish. The text is the endpoint for a procession, which involves a royal elite ascending a stage to read a portion of it aloud. This engagement with the text solidifies the heir’s relationship to the city gods and his authority over the city’s denizens (Gilibert 2022).you yourself shall make him great in my hand.”

3. Texts in Southern Levantine Rituals

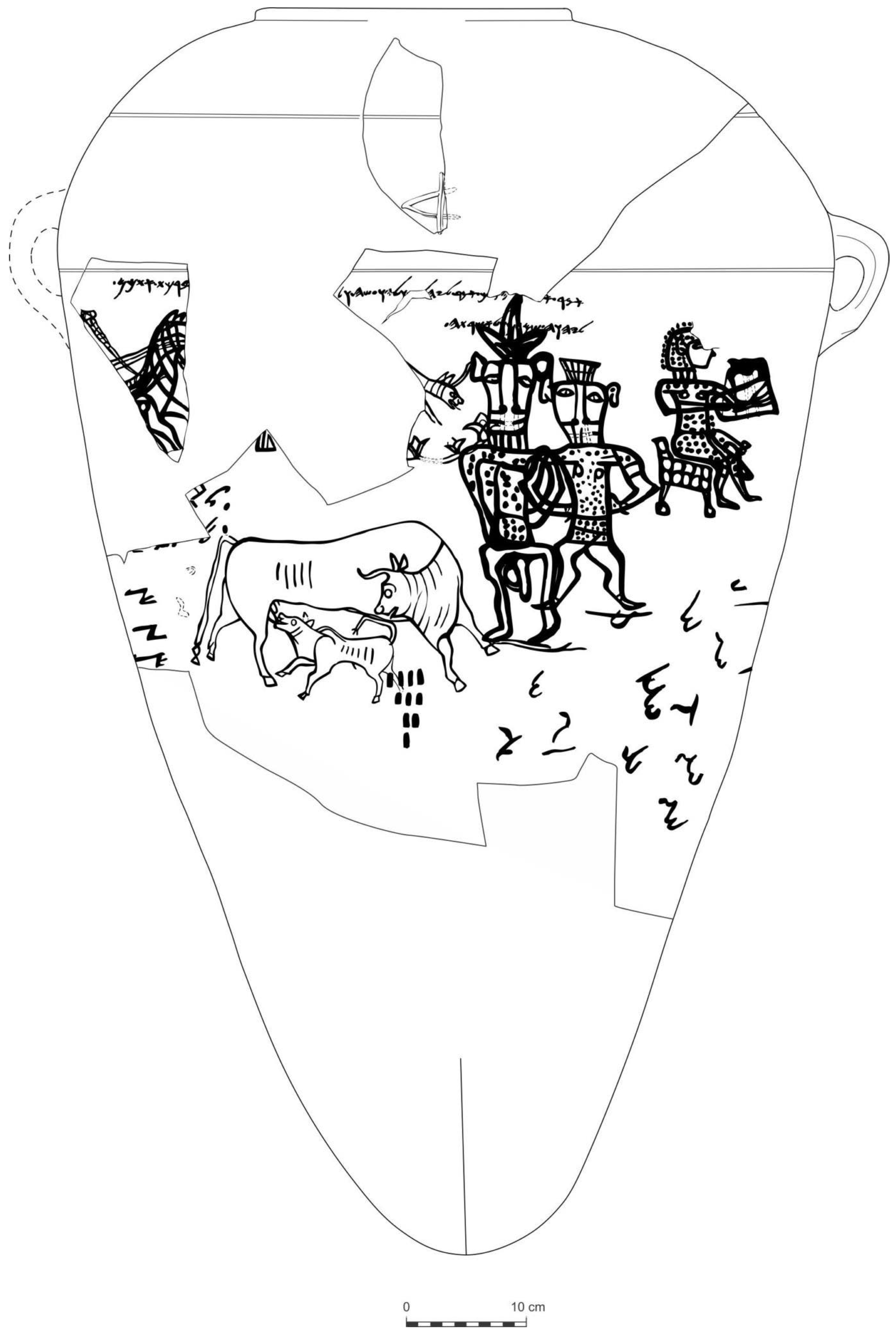

3.1. Kuntillet ʿAjrud

[W]ytnw.l[y]hwh[.]tymn.wlʾšrth

This same inscription was directly addressed to an audience—perhaps the personnel responsible for reading to Yahweh and Asherata. KA 4.1 begins with the heading [l]nʿry.˹ś˺rʿr “[For] the Apprentices of the Commander of the Fortress,” an address reminiscent of biblical psalm headings (Schniedewind 2019, p. 42). The text following this address and indeed all the plaster texts at Kuntillet ʿAjrud are poetic or “hymno-epic” compositions that may represent extra-biblical Israelite psalms (Mandell 2012, pp. 134–50; Schniedewind 2019, pp. 158–64; Smoak and Schniedewind 2019). While most of these inscriptions had fallen when they were discovered, the only plaster inscription found in situ on a wall at Kuntillet ʿAjrud (KA 4.3) was presented at eye level, implying that it was to be read (Mandell 2022b, p. 275). One of the duties of personnel stationed at similar gateways in Assyrian palaces was to guide those allowed entry through the space beyond, perhaps reading the inscriptions there (Groß and Kertai 2019, pp. 12–18).“And may they recount to Yahweh of Teman and Asherata.”10

lʿbdyw bn ʿdnh brk hʾ lyhw

KA 1.3—and likely the other stone bowls—performatively claims a blessing upon the individual who donated it (Mandell 2022a, pp. 353–4). These bowls were likely ritual implements themselves. Stone bowls with dedicatory inscriptions are also known from Karkemish, including a bowl installed by Yarrari that specifies that it was a libation basin (Hawkins 2012, pp. 139–40).13 The text draws attention to the ritual use of the artifact even without making its function explicit.“Belonging to Ōbadyāw, son of ʿAdnā. May he be blessed by YHW.”

šḥt qyn šdh wmrm h[rm…]

In the same context, KA 4.2 line 2 announces:the Kênite destroyed a mountain and lofty mou[ntain range…]”

wbzrḥ.ʾl.br[m]

It is notable that these references to the topography of the site and its surroundings appear in the inscriptions near the entrance of the fortress, where they emphasize the transition from wilderness to civilization.“And when Ell shines forth on the hei[ghts.]”

ʾmr.ʾ[šyw.]hm[l]k.ʾmr.lyhl˹y˺.wlywʿśh.wl[…]brkt.ʾtkm.

lyhwh.šmrn.wʾšrth

This blessing is given by a king ʾšyw “Ashyaw.” Schniedewind reads this as a sample letter from a fictional king, but nevertheless one who has an Israelite name to match the northern toponym (Schniedewind 2023, pp. 209–10). Some scholars have proposed that Ashyaw is simply a transposed reading of the name Joash, who may have been the builder of the site (Meshel 1986; Hadley 1987, p. 182). The inscription might represent a real charter from Samaria installed at this southern fort that took the form of an invocation (Mandell 2012). Perhaps this was performed aloud like the invocations at Karkemish when the pithos was installed. In any case, it implies the personnel stationed in the fortress were operating under the aegis of the Israelite king and perhaps even implies travel from Samaria to Kuntillet ʿAjrud.“Message of A[šyaw,] the k[in]g: “Say to Yaheli and to Yoʿasah and to [PN]. I have blessed you by Yahweh of Samaria and Asherata.”14

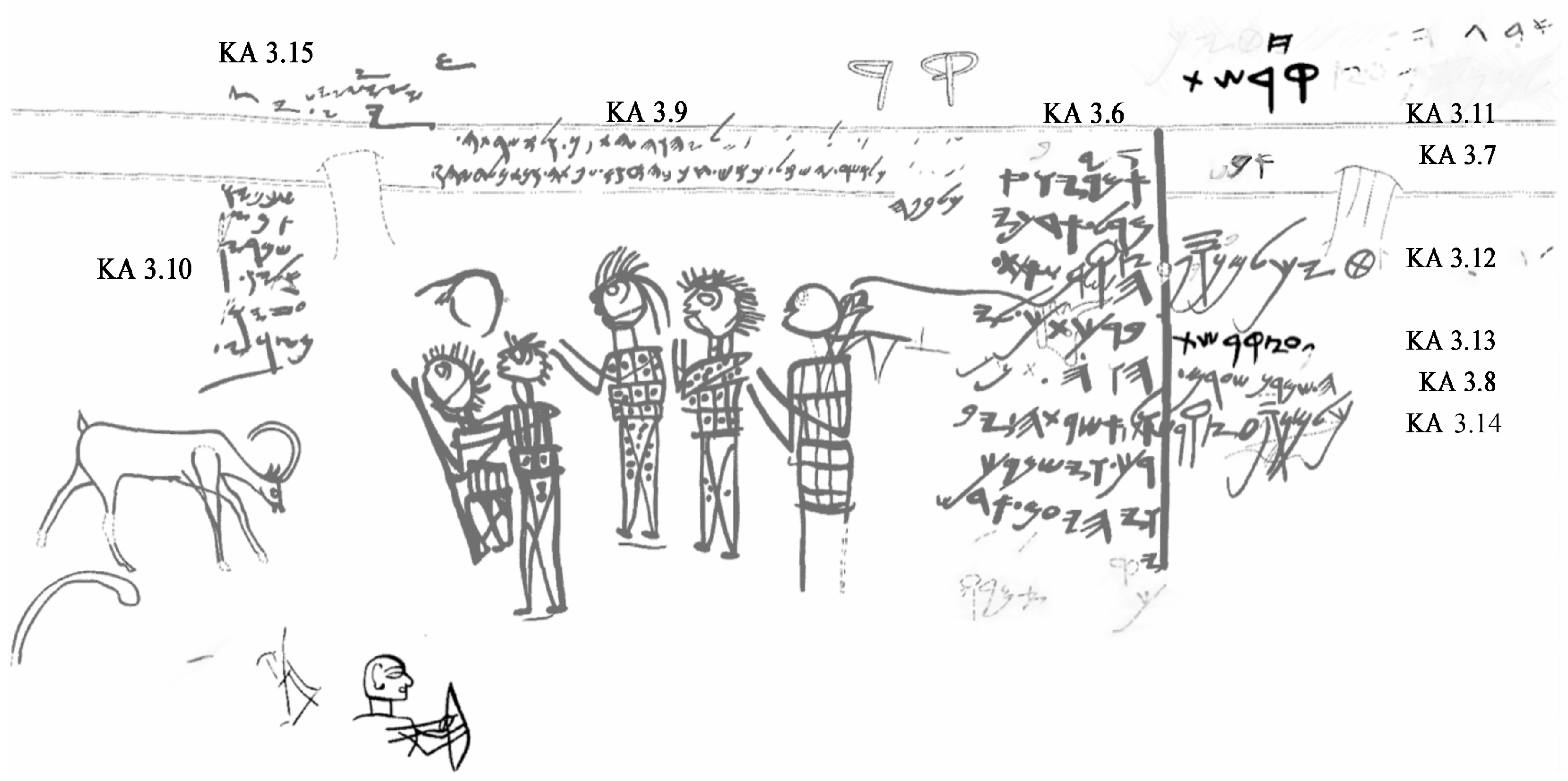

3.2. Tell Deir ʿAlla

ṫṗry . skry . šmyn . bʿbky . šm . ḥšk . wʾl . ngh . ʿṭm . wʾ[l .] skrky . thby . ḥt[m . ] ḃ . ḥšk . wʾl[.]thgy . ʿd . ʿlm

The text marks its location by reference to its environment, much like the references to the surrounding desert in the Kuntillet ʿAjrud plaster texts (Virnelson 2024, p. 479). If the text were encountered during a storm, the flickering light reflecting off the surface would have heightened the viewer’s experience of the storm outside. This would have been particularly palpable when the text was performed aloud. Special ritual invocations performed alongside thunderstorms are attested in the northern Levant, though only in the Late Bronze Age (Barsacchi 2019).“Fasten the bolts of the heavens with your cloud. There, there will be darkness, and for brightness there will be gloom. And on your bolt, you shall place a dark seal, and do not remove it forever.”

ldʿt . spr . dbr . lšmr . ʿl . lšn . lk

Wearne suggests that a ritual specialist would have performed the text before a seated audience, who were imitating the posture of the addressees within the narrative. The narrative thus served a partially hypertextual function. He argues that the text was used as a mnemonic aid rather than as a script (Wearne 2018, pp. 135–38). A similar argument has been advanced for Mesopotamian ritual texts and some biblical texts (Abusch 2015, p. 175; Ramos 2021, pp. 57, 120–21), so this is a plausible reconstruction for all of the performances analyzed thus far. In any case, the text was directly engaged in a performance before an audience.”Heed the text! Speak and retain it orally (literally, “on tongue”)!”

4. Discussion: The Sitz im Leben of Ritualized Texts in the Iron II Levant

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KAI | Kanaanäische und Aramäische Inschriften |

| KA | Kuntillet ʿAjrud |

| 1 | See, for example, the texts at Tell Halaf and Zincirli (Gilibert 2013; Struble and Herrmann 2009; Hogue 2022). |

| 2 | The Phu, Pho, and PhSt are also known as KAI 26 A, B, and C, respectively. |

| 3 | This is the text as preserved in Hu, but Ho reads nearly identically, with only minor spelling variations. |

| 4 | This translation is my own, but it follows the collation of the text proposed by Amadasi Guzzo (Amadasi Guzzo 2000, p. 79). Also, it may be worth noting the strong parallel between Azatiwada’s triannual pilgrimage and the Shalosh Regalim, the prescription of which, in Exod 23:14–17, even gives one of the three festivals the exact same name as one of Azatiwada’s—qṣ(y)r. |

| 5 | The depiction of a text-bearing artifact in miniature as a significant component of some spectacle is attested elsewhere in both Syro-Anatolian and Neo-Assyrian art (Hogue 2019, p. 331; Watanabe 2020). |

| 6 | For a full review of the sculpture and architecture, see the relevant chapters by Gilibert and Hogue (Gilibert 2011, pp. 19–54; Hogue Forthcoming). |

| 7 | This is Hawkins’ revised transliteration and translation of KARKAMIŠ A23 §§7–8 (Hawkins 2024, p. 198). |

| 8 | Israel was sending emissaries to the palaces in Nimrud during the same period; so, this may provide the vector of transmission for artistic and architectural motifs to be emulated at Kuntillet ʿAjrud (Aster 2016; Na’aman 2019). |

| 9 | See also the enthroned figure of Bar-Rakib at Zincirli, which similarly designates the final waypoint in a ritual procession (Hogue 2022, pp. 46–47) |

| 10 | This translation is mine, but it follows a suggestion from (Schniedewind 2019, p. 161). |

| 11 | In this regard, it is worth noting that the scribal exercises on Pithos A are only legible when it is rotated 180 degrees, suggesting that it was reused in the bench-room secondarily. Perhaps Pithos A was originally installed closer to Pithos B within the courtyard. |

| 12 | This bowl was found in the southern portion of the courtyard past the bench-room, but it is suspected to have originally been installed on the second floor of Building A. |

| 13 | Additional stone bowls thought to originate at Karkemish include KARKAMIŠ A16e and KARKAMIŠ A18i. Two dedicatory stone bowls were discovered at Babylon (BABYLON 2 and BABYLON 3), but they are thought to have originated in the Storm-God Temple at Aleppo. BEIRUT is a stone bowl of unknown provenance, though its signs resemble those of Karkemish (Hawkins 2012, pp. 198–200, 394–97, 558–59). Finally, the rim of a stone bowl of comparable size to those from Kuntillet ʿAjrud, inscribed with a similar dedicatory formula, was discovered at Baluʿ on the Kerak Plateau (Zayadine 1986). |

| 14 | The translation here primarily follows Schniedewind, though I follow Hess in reading the last word as the name “Asherata”, rather than as “his asherah” (Schniedewind 2019, p. 105; Hess 2025). |

| 15 | A similar assemblage (albeit with more obvious ritual vessels) has been so interpreted at Tel Reḥov (Panitz-Cohen and Mazar 2022). |

| 16 | This translation follows Wearne, except that I translate spr as “text,” seeing it as a reference to the inscribed artifact, based on its usage in other epigraphic contexts, like the Kulamuwa Orthostat (KAI 24:14–15) and the Sefire Treaties (KAI 222 A1:6, 8; 2:23, 28, 33; B2:9, 18). |

References

- Abusch, Tzvi. 2015. Writings from the Ancient World 37. In The Witchcraft Series Maqlû. Atlanta: SBL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Amadasi Guzzo, Maria Giulia. 2000. MSKT à Karatepe. Orientalia 69: 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Angelo, Dante. 2014. Assembling Ritual, the Burden of the Everyday: An Exercise in Relational Ontology in Quebrada de Humahuaca, Argentina. World Archaeology 46: 270–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aster, Shawn Zelig. 2016. Israelite Embassies to Assyria in the First Half of the Eighth Century. Biblica 97: 175–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrani, Zainab. 2014. The Infinite Image: Art, Time and the Aesthetic Dimension in Antiquity. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Barsacchi, Francesco. 2019. “When the Storm-God Thunders”: Some Considerations on Hittite Thunder Festivals. Corum: TUR. Available online: https://iris.unito.it/handle/2318/1905141 (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Blum, Erhard. 2016. Die Altaramäischen Wandinschriften Vom Tell Deir ʻAlla Und Ihr Institutioneller Kontext. In Metatexte: Erzählungen von Schrifttragenden Artefakten in Der Alttestamentlichen Und Mittelalterlichen Literatur. Edited by Michael R. Ott and Friedrich-Emanuel Focken. Materiale Textkulturen 15. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Boertien, Jeannette H. 2008. Unraveling the Threads: Textiles and Shrines in the Iron Age. In Sacred and Sweet: Studies on the Material Culture of Tell Deir ʿAlla and Tell Abu Sarbut. Edited by Margreet L. Steiner and Eveline J. Van der Steen. Ancient Near Eastern Studies, Supplement 24. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, Joel S. 2018. Prophecy in Transjordan: Balaam Son of Beor. In Enemies and Friends of the State: Ancient Prophecy in Context. Edited by Christopher A. Rollston. University Park: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Charney, Davida. 2024. The Centrality of Individual Petitions in Temple Rituals: Hannah, Solomon, and First-Person Psalms. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 48: 513–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çambel, Halet. 1999. Corpus of Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions, Volume II: Karatepe-Aslantaş. Studies in Indo-European Language and Culture, 8.2. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Çambel, Halet, and Aslı Özyar. 2003. Karatepe-Aslantaş, Azatiwataya: Die Bildwerke. Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- DeMarrais, Elizabeth. 2014. Introduction: The Archaeology of Performance. World Archaeology 46: 155–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, Faris. 2022. Notes on the Karatepe Storm-God Tarhunza Usanuwami and Baal Krntryš. Anatolian Research 25: 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denel, Elif. 2007. Ceremony and Kingship at Carchemish. In Ancient Near Eastern Art in Context: Studies in Honor of Irene J. Winter by Her Students. Edited by Jack Cheng and Marian Feldman. Leiden: Brill. Available online: https://brill.com/edcollbook/title/12576 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Dever, William G. 1984. Asherah, Consort of Yahweh? New Evidence from Kuntillet ʿAjrûd. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 255: 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dever, William G. 2005. Did God Have a Wife? Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- de Martino, Stefano. 2014. Il Ruolo Politico Di Karkemish in Siria Durante Il Periodo Imperiale Ittita. In Karkemish: An Ancient Capital on the Euphrates. Edited by Nicolò Marchetti. Bologna: Ante Quem. [Google Scholar]

- Elliff, Bryan, and Robert Coleman. 2023. ‘Fasten the Bolts of Heaven’: A New Interpretation of a Difficult Line of the Deir ʿAlla Plaster Texts (I.6). Semitica 65: 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Falsone, Gioacchino, and Paola Sconzo. 2007. The ‘Champagne-Cup’ Period at Carchemish. A Review of the Early Bronze Age Levels on the Acropolis Mound and the Problem of the Inner Town. In Euphrates River Valley Settlement: The Carchemish Sector in the Third Millennium BC. Edited by Edgar Peltenburg. Harvard: Oxbow. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, Israel. 2013. Notes on the Historical Setting of Kuntillet ʿAjrud. Maarav 20: 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, Hendricus J. 2008. Deir ʿAlla and Its Religion. In Sacred and Sweet: Studies on the Material Culture of Tell Deir ʿAlla and Tell Abu Sarbut. Edited by Margreet L. Steiner and Eveline J. Van der Steen. Ancient Near Eastern Studies, Supplement 24. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Frolov, Serge. 2020. Psalms: Sitz Im Leben vs. Sitz in Der Literatur. In Petitioners, Penitents, and Poets: On Prayer and Praying in Second Temple Judaism. Edited by Ariel Feldman and Timothy J. Sandoval. Beihefte Zur Zeitschrift Für Die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 524. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Garr, W. Randall. 2004. Dialect Geography of Syria-Palestine 1000-586 BCE. University Park: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Gilibert, Alessandra. 2011. Syro-Hittite Monumental Art and the Archaeology of Performance: The Stone Reliefs at Carchemish and Zincirli in the Earlier First Millennium BCE. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilibert, Alessandra. 2013. Death, Amusement and the City: Civic Spectacles and the Theatre Palace of Kapara, King of Gūzāna. Kaskal 10: 35–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilibert, Alessandra. 2022. Children of Kubaba: Serious Games, Ritual Toys, and Divination at Iron Age Carchemish. Religions 13: 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusfredi, Federico. 2010. Sources for a Socio-Economic History of the Neo-Hittite States. Texte Der Hethiter 28. Berlin: Universitätsverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Groß, Melanie, and David Kertai. 2019. Becoming Empire: Neo-Assyrian Palaces and the Creation of Courtly Culture. Journal of Ancient History 7: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunkel, Hermann. 1926. Die Psalmen. Göttinger Handkommentar zum Alten Testament 2. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, Jo Ann. 1980. The Balaam Text from Deir ʿAlla. Chico: Scholars Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hadley, Judith M. 1987. Some Drawings and Inscriptions on Two Pithoi from Kuntillet ?Ajrud. Vetus Testamentum 37: 180–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilakis, Yannis. 2013. Archaeology and the Senses: Human Experiences, Memory, and Affect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, John David. 2012. Corpus of Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions. Vol 1, Inscriptions of Hte Iron Age. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, John David. 2024. Corpus of Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions: Volume III: Inscriptions of the Hittite Empire and New Inscriptions of the Iron Age. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, John David, and Mark Weeden. 2016. Sketch History of Karkamish in the Earlier Iron Age (Iron I-IIB). In Carchemish in Context: The Land of Carchemish Project, 2006–2010. Edited by Tony J. Wilkinson, Edgar Peltenburg and Eleanor Barbanes Wilkinson. Harvard: Oxbow Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, Richard S. 2025. New Evidence for Asherata/Asherah. Religions 16: 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodder, Ian. 2006. The Spectacle of Daily Performance at Çatalhöyük. In Archaeology of Performance: Theatres of Power, Community, and Politics. Edited by Takeshi Inomata and Lawrence S. Coben. Lanham: Rowman Altamira. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, Ian. 2012. Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships Between Humans and Things. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Hogue, Timothy. 2019. ‘I Am’: The Function, History, and Diffusion of the Fronted First-Person Pronoun in Syro-Anatolian Monumental Discourse. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 78: 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogue, Timothy. 2021a. Thinking Through Monuments: Levantine Monuments as Technologies of Community-Scale Motivated Social Cognition. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 31: 401–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogue, Timothy. 2021b. With Apologies to Hazael: The Counter-Monumentality of the Tel Dan Stele. Hebrew Bible and Ancient Israel 10: 243–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogue, Timothy. 2022. In the Midst of Great Kings: The Monumentalization of Text in the Iron Age Levant. Manuscript and Text Cultures (MTC) 1: 13–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogue, Timothy. 2023a. Language in Israel and Judah: A Sociolinguistic Reappraisal. In The Ancient Israelite World. Edited by Kyle H. Keimer and George A. Pierce. Routledge Worlds. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hogue, Timothy. 2023b. The Ten Commandments: Monuments of Memory, Belief, and Interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogue, Timothy. 2024. Bulls on Parade: Metal Bovines, Pilgrimage Networks, and the Struggle for Israelite Identity in 1 Kings 12:25–33. Avar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Life and Society in the Ancient Near East 3: 2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogue, Timothy. 2025a. Building Monuments to Build Communities: Monumental Space as Public Space in the Iron Age Levant. In Space and Communal Agency in Pre-Modern Societies. Edited by Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia. Harvard: Oxbow Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hogue, Timothy. 2025b. From the Monumental to the Mundane: A Material Engagement Approach to Power in the Ancient Near East. In Understanding Power in Ancient Egypt and the Near East, Volume I: Approaches. Edited by Shane M. Thompson and Jessica Tomkins. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hogue, Timothy. Forthcoming. The Cityscape of Carchemish: A History of Urban Planning at a Major Syro-Anatolian Capital. In The Shapes and Functions of Cities in Ancient Mesopotamia and Its Surroundings. Edited by Shigeo Yamada, Timothy Hogue and Katsuji Sano. Cities in West Asia and North Africa through the Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, Liora Kolska, Shlomo Hellwing, Omri Lernau, and Henk K. Mienis. 2012. The Faunal Remains and the Function of the Site. In Kuntillet ʿAjrud (Ḥorvat Teman): An Iron Age II Religious Site on the Judah-Sinai Border. Edited by Ze’ev Meshel. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, Kathleen L. 2014. Ritual as Performance in Small-Scale Societies. World Archaeology 46: 164–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Moawiyah M., and Gerrit Van der Kooij. 1991. The Archaeology of Deir ʿAlla Phase IX. In The Balaam Text from Deir ʿAlla Re-Evaluated. Edited by Jacob Hoftijzer and Gerrit Van der Kooij. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Inomata, Takeshi, and Lawrence S. Coben. 2006. Overture: An Invitation to the Archaeological Theater. In Archaeology of Performance: Theatres of Power, Community, and Politics. Edited by Takeshi Inomata and Lawrence S. Coben. Lanham: Rowman Altamira. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, Dan, and Andrea Ricci. 2016. Long-Term Settlement Trends in the Birecik-Carchemish Sector. In Carchemish in Context: The Land of Carchemish Project, 2006–2010. Edited by Tony J. Wilkinson, Edgar Peltenburg and Eleanor Barbanes Wilkinson. Harvard: Oxbow Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire, André. 1981. Les Écoles et La Formation de La Bible Dans l’ancien Israël. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire, André. 2016. The Kuntillet ‘Ajrud Inscriptions Forty Years After Their Discovery. In Alphabets, Texts and Artifacts in the Ancient Near East: Studies Presented to Benjamin Sass. Edited by Israel Finkelstein, Christian Robin and Thomas Römer. Paris: Van Dieren éditeur. [Google Scholar]

- Malafouris, Lambros. 2013. How Things Shape the Mind: A Theory of Material Engagement. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mandell, Alice. 2012. ‘I Bless You to YHWH and His Asherah’—Writing and Performativity at Kuntillet ʿAjrud. Maarav 19: 131–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandell, Alice. 2022a. More than the Sum of Their Parts: Multimodality and the Study of Iron Age Inscriptions. In The Ancient Israelite World. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mandell, Alice. 2022b. ‘Top-Down’ and ‘Bottom-up’ Monumentality at Kuntillet ’Ajrud: The Evolution of the Benchroom at Kuntillet ’Ajrud as a Communal Monument. Hebrew Bible and Ancient Israel 10: 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, Natalie Naomi. 2014. City Gates and Their Functions in Mesopotamia and Ancient Israel. In The Fabric of Cities: Aspects of Urbanism, Urban Topography and Society in Mesopotamia, Greece and Room. Edited by Natalie Naomi May and Ulrike Steinert. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Meshel, Ze’ev. 1986. The Inscriptions of Kuntillet ʿAjrud. Paper presented at 12th Congress of the International Organization for the Study of the Old Testament, Jerusalem, Israel, August 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Meshel, Ze’ev. 2012. Kuntillet ʿAjrud: An Iron Age II Religious Site on the Judah-Sinai Border. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Micu, Andreea S. 2022. Performance Studies: The Basics. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mowinckel, Sigmund. 1962. The Psalms in Israel’s Worship. Translated by D. R. Ap-Thomas. Oxford: I. Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Na’aman, Nadav. 2013. A New Outlook at Kuntillet ʿAjrud and Its Inscriptions. Maarav 20: 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na’aman, Nadav. 2019. Samaria and Judah in an Early 8th-Century Assyrian Wine List. Tel Aviv 46: 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornan, Tallay. 2016. Sketches and Final Works of Art: The Drawings and Wall Paintings of Kuntillet ‘Ajrud Revisited. Tel Aviv 43: 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyar, Aslı. 2013. The Writing on the Wall: Reviewing Sculpture and Inscription on the Gates of the Iron Age Citadel of Azatiwataya (Karatepe-Aslantaș). In Cities and Citadels in Turkey: From the Iron Age to the Seljuks. Edited by Scott Redford and Nina Ergin. Ancient Near Eastern Studies, Supplement 40. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Özyar, Aslı. 2021. Signs Beyond Boundaries: The Visual World of Azatiwataya. In Beyond All Boundaries: Anatolia in the First Millennium BC. Edited by Annick Payne, Šárka Velhartická and Jorit Wintjes. Orbis Bibliscus et Orientalis 295. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Panitz-Cohen, Nava, and Amihai Mazar. 2022. The Exceptional Ninth-Century BCE Northwestern Quarter at Tel Reḥov. Near Eastern Archaeology 85: 132–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, Annick. 2010. Hieroglyphic Luwian: An Introduction with Original Texts. Subsidia et Instrumenta Lingua Rum Orientis 2. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Perrot, Jean, ed. 2013. The Palace of Darius at Susa: The Great Royal Residence of Achaemenid Persia. Gérard Collon, trans. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Puech, Émile. 2008. Balaʿam and Deir ʿAlla. In The Prestige of the Pagan Prophet Balaam in Judaism, Early Christianity and Islam. Leiden: Brill. Available online: https://brill.com/display/book/edcoll/9789047433132/Bej.9789004165649.i-329_003.xml (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Ramos, Melissa D. 2021. Ritual in Deuteronomy: The Performance of Doom. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, Margaret Cool. 2015. Achaemenid Imperial Architecture: Performatie Porticoes of Persepolis. In Persian Kingship and Architecture: Strategies of Power in Iran from the Achaemenids to the Pahlavis. Edited by Sussan Babaie and Talinn Grigor. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Brian B. 2002. The Iron Age Pithoi Drawings from Ḥorvat Teman or Kuntillet ʿAjrud: Some New Proposals. Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Studies 2: 91–125. [Google Scholar]

- Schniedewind, William M. 2019. The Finger of the Scribe: How Scribes Learned to Write the Bible. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schniedewind, William M. 2023. Adaptation in Scribal Curriculum: Examples from the Letter Writing Genre. In The Scribe in the Biblical World: A Bridge Between Scripts, Languages and Cultures. Edited by Esther Eshel and Michael Langlois. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Skeates, Robin. 2016. Experiencing Darkness and Light in Caves: Later Prehistoric Examples from Seulo in Central Sardinia. In The Archaeology of Darkness. Edited by Marion Dowd and Robert Hensey. Harvard: Oxbow Books. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoak, Jeremy D. 2017. Inscribing Temple Space: The Ekron Dedication as Monumental Text. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 76: 319–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoak, Jeremy D., and William Schniedewind. 2019. Religion at Kuntillet ʿAjrud. Religions 10: 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, Margreet L. 2019. Iron Age Cultic Sites in Transjordan. Religions 10: 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struble, Eudora J., and Virginia Rimmer Herrmann. 2009. An Eternal Feast at Samʾal: The New Iron Age Mortuary Stele from Zincirli in Context. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 356: 15–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Shane M. 2023. Displays of Cultural Hegemony and Counter-Hegemony in the Late Bronze and Iron Age Levant: The Public Presence of Foreign Powers and Local Resistance. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinka, Eric M. 2022. A New Mobilities Approach to Naming and Mapping Deities: Presence, Absence, and Distance at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud. In Naming and Mapping the Gods in the Ancient Mediterranean: Spaces, Mobilities, Imaginaries. Edited by Thomas Galoppin, Elodie Guillon, Max Luaces, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar, Sylvain Lebreton, Fabio Porzia, Jörg Rüpke, Emiliano Rubens Urciuoli and Corinne Bonnet. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Victor. 1986. Anthropology of Performance. New York: PAJ Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Uehlinger, Christoph. 2016. Learning by Doing—Distinguishing Different Hands at Work in the Drawings and Paintings of Kuntillet ʿAjrud. In Alphabets, Texts and Artifacts in the Ancient Near East: Studies Presented to Benjamin Sass. Edited by Israel Finkelstein, Christian Robin and Thomas Römer. Paris: Van Dieren éditeur. [Google Scholar]

- Vayntrub, Jacqueline. 2024. ‘Nothing Beside Remains’: Ephemerality and Endurance in Biblical Textuality. Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 100: 409–26. [Google Scholar]

- Virnelson, Leslie. 2024. Daubing, Materiality, and Prophecy in Ezekiel 13:10–16. The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 86: 469–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Dassow, Eva. 2020. Nation Building in the Plain of Antioch from Hatti to Hatay. In Perspectives on the History of Ancient Near Eastern Studies. Edited by Garcia-Ventura and Lorenzo Verderame. University Park: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Kazuko. 2020. Adoration of Oath Documents in Assyrian Religion and Its Development. Orient 55: 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, James W. 2021. Texts Are Not Rituals, and Rituals Are Not Texts, with an Example from Leviticus 12. In Text and Ritual in the Pentateuch: A Systematic and Comparative Approach. Edited by Christophe Nihan and Julia Rhyder. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Wearne, Gareth. 2018. ‘Guard It on Your Tongue!’: The Second Rubric in the Deir ʿAlla Plaster Texts as an Instruction for the Oral Performance of the Narrative. In Registers and Modes of Communication in the Ancient Near East: Getting the Message Across. Edited by Kyle H. Keimer and Gillan Davis. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, Irene J. 1979. On the Problems of Karatepe: The Reliefs and Their Context. Anatolian Studies 29: 115–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubovich, Ilya. 2017. The Luwian word for ‘place’ and its cognates. Kadmos 56: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubovich, Ilya. 2020. Doing Things Reverently among the Luwians. Les Études Classiques 88: 1–4. Available online: http://lesetudesclassiques.be/index.php/lec/article/view/697 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Younger, K. Lawson, Jr. 1998. The Phoenician Inscription of Azatiwada: An Integrated Reading. Journal of Semitic Studies 40: 11–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayadine, Fawzi. 1986. The Moabite Inscription. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 30: 302–4. [Google Scholar]

- Zevit, Ziony. 2001. The Religions of Ancient Israel: A Synthesis of Parallactic Approaches. Singapore: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Ziffer, Irit. 2014. ‘We must have a king over us, that we may be like all the other nations’ (I Sam 8:19): Israelite Kings in Art. Shnaton: An Annual for Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies 23: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hogue, T. Texts, Architecture, and Ritual in the Iron II Levant. Religions 2025, 16, 1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091178

Hogue T. Texts, Architecture, and Ritual in the Iron II Levant. Religions. 2025; 16(9):1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091178

Chicago/Turabian StyleHogue, Timothy. 2025. "Texts, Architecture, and Ritual in the Iron II Levant" Religions 16, no. 9: 1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091178

APA StyleHogue, T. (2025). Texts, Architecture, and Ritual in the Iron II Levant. Religions, 16(9), 1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091178