1. Introduction

Acknowledging the growing debates on how [or whether or not] human interaction with nature is influenced by religious beliefs (

Jenkins and Chapple 2011), this paper focuses on how the idea of “religion” by Indigenous communities is constituted through their everyday relationship with the local environment maintained through various religious practices. Indigenous religions are difficult to define, as they appear in complex forms, varying across different regions and communities. While a romanticised notion of Indigenous religions or knowledge per se may portray it as something extraordinary and separated from the real world, anthropologist Toni Huber calls such religious practices “mundane practices” (

Huber 1999). Huber advocates understanding Indigenous religious systems as integral to how people live, relate to their environment, and form their communities rather than as distant, mysterious, and separated (

Huber 1999). The eastern Himalayas provide a suitable site for understanding such forms of Indigenous religious practices, as it hosts diverse Indigenous communities with multiple religious traditions. Most of these traditions in the Eastern Himalayas continue to thrive through their knowledge and customary systems of governance or traditional institutions, often guided by numerous eco-spiritual practices in diverse forms. However, over the years, it has become a subject of debate among scholars arguing for the scientific validity of the Indigenous knowledge system from different epistemological standpoints. Some lauded Indigenous Knowledge as an “alternative collective wisdom relevant to a variety of matters at a time when existing norms, values, and laws are increasingly called into question” (

Berkes 1993, p. 7). This came in the backdrop of the Brundtland Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (1987), which called for the recognition and protection of Indigenous people and their knowledge because of their ability to contribute to local, regional, and global sustainability (

Higgins 1998, p. 323). The recent scholarly endeavour to decolonise Indigenous knowledge questions the continuous tapestry of the colonial West in the framing of knowledge as Indigenous/Traditional Knowledge in the North Academic World. They question how the Western concept has found a way into native lexicons and current environmental consciousness (

Smyer Yü et al. 2025, p. 11) and colonise the native understanding of the “environment”. By challenging the artificial division of the Global North and the Global South, this group of scholars opens a space for interweaving traditional knowledge with scientific counterparts while discussing the relationship between the environment and Indigenous communities (

Smyer Yü et al. 2025). This perspectival shift from the Global to the Planetary in their work, in a way, debunked the chasm between Western Science and Indigenous knowledge (primarily referred to as Traditional Environmental Knowledge) that has evaporated since the 1980s. Therefore, one can argue that Western techno-scientific approaches are in themselves an insufficient response to today’s complex web of social, economic, political, and environmental challenges and hence require a more humanistic approach (

Wouters 2025).

We align this article with the same line of considering Indigenous knowledge about their environment as a pluriverse space of humans and more-than-humans co-created and nurtured through constant interaction with the spirits/deities.

1 Following Huber’s proposition of Indigenous religious practices as mundane activities, deeply embedded in the everyday lives of their practitioners and not separate from ordinary, daily life, this paper focuses on everyday practices of spirit worship by different Indigenous communities. It shows how ecological cosmology is framed among Indigenous communities in everyday interaction with the local environment and how such practices co-exist/negotiate with the larger religious traditions that have come to dominate the regions in different historical periods. In all these, spirits profoundly shape Indigenous religious practices’ worldviews and traditions. Perhaps the spirits in Indigenous religions are a life force that animates all living entities of the planet and protects them from various illnesses and destruction. Therefore, “healing” constitutes an essential component of Indigenous religious practices in which different kinds of spirits guide the Indigenous lifeway and maintain their relationship with locally specific environmental flows and non-human species. Additionally, the recognition of spirit (both good and evil)

2 as a significant factor in Indigenous religion allows one to understand the diverse ways in which cosmology is created and maintains boundaries between the human-inhabited world and the non-human domain. Thus, we believe that the scholarly endeavours to foreground this kind of spirit worship as an essential element of Indigenous religion offer a new epistemic lens to move away from the intellectual shackles of Western Indigenous knowledge. Moreover, the notion of Indigenous knowledge, particularly in the tradition of spirit worship and healing, often involves specific ritual specialists such as shamans. These individuals possess a deep understanding of the tradition and are recognised for their authority and expertise within their communities. However, this recognition does not lead to a significant hierarchical structure among practitioners. Instead, there is typically some form of economic or material compensation provided to these ritual specialists as part of Indigenous religious practices.

Notably, the issues of indigeneity in the Eastern Himalayas have been well-researched topics among anthropologists, sociologists, and historians over the last few decades (

Chettri 2017;

Middleton 2015;

Shneiderman 2015) and politically contested; however, it leads us to the circuit of cultural nationalism where native voices, particularly in areas discussed in this paper, were reduced into a mere harbinger of anti-colonial movement and the torchbearer of Indigenous identities. This, which we call “obligatory nativism”, made “nativeness coming through lived experience” afraid of scientific rigour and often fails to address “native voices” in its efforts to defend the intellectually trapped Indigenous wisdom (

Smyer Yü et al. 2025). This paper, while acknowledging the devastation of colonialism and the obligation of post-colonialism nativism, aims to offer everyday practices of Indigenous religious practices in the eastern Himalayas through scientific research and our experience as Indigenous scholars from the region.

Based on ethnographic fieldwork conducted by both scholars in two different settings of Assam and the Darjeeling Hills in India, this article aims to contextualise the Indigenous knowledge about the local environment and different species (animals, plants, rivers, and spirits) as an essential aspect of eco-spirituality performed through different rites and rituals. The areas where we conducted our ethnographic fieldwork have faced ecological vulnerabilities amidst extractive development regimes since colonial times. The Indigenous communities have faced political marginalisation in these areas and have undertaken prolonged struggles asserting their indigeneity. Amidst these socio-political struggles, acts of “healing” and “nurturing” form integral parts of the Indigenous worldview in these areas. We strongly believe that the case of Indigenous communities in these areas can contribute to new research in religion and ecology.

The authors belong to different ethnic backgrounds, affiliating with our native languages and identities. Sangay Tamang belongs to one of the ethnic groups (Tamang) of the larger Nepali heritage in Darjeeling Hills, West Bengal, where Nepali is the

lingua franca and Pranab K. Pegu belongs to the Mising tribe in Assam, who speak the Mising language. The fieldwork for this paper was not part of any collaborative work; rather, it emerged from our respective doctoral research and some other independent research projects. The fieldwork in Darjeeling was conducted from late 2017 to early 2022, where different in-depth interviews were conducted with different shamans and community members of different ethnic groups in the Darjeeling Himalayas. The fieldwork in Assam was conducted from early 2021 to early 2024 amongst the Mising

3 tribe in a village called Bélang and with people who make a living from the river Obonori

4 (Subansiri) in the Mingmang Panchayat of Dhemaji district of eastern Assam, in the foothills bordering Arunachal Pradesh.

Despite coming from different social, cultural, and political backgrounds, we share a common research interest in the issues of colonialism, indigeneity, environmental conservation, and capitalist development, which have transformed our place and society in their respective ways. We also share common research themes and lived experiences regarding Indigenous religious traditions, rituals, and practices that have made us write this paper together. Among many different themes of religion and ecology, we consider the reverence of spirit as the connecting point between these two places in the Eastern Himalayas, where the ideas of healing, protection, and well-being are deeply embedded. Therefore, the outcome of this research paper emerged through a decade of research engagement with the communities and our respective lived experiences as Indigenous people of our region.

2. Colonialism, Religions, and Indigenous Communities in the Eastern Himalayas

The rising push for extractive development and a market-based economy in the Himalayas has threatened Indigenous communities and their way of life, leading to the refashioning of values assigned to land and forest resources (

Karlsson [2011] 2023;

Kikon 2019;

Kikon and Karlsson 2019). Additionally, geopolitics in the Himalayas, particularly in the Eastern Himalayas, has made the community and regions vulnerable to large-scale militarisation of the landscape that limits their mobility and access to local resources (

Kikon 2019). The mode of resistance against the marginalisation of Indigenous communities has produced numerous Indigenous movements, mostly emanating from their ethnic identity and claim for “nationality.” Therefore, the term “indigeneity” differs vastly in terms of regional politics, nationalist agendas, and community assertions of identity and belongingness. However, the vulnerabilities and marginalities of Indigenous communities in the Eastern Himalayas are deeply rooted in the history of colonialism that brought tremendous transformation in their relationship with the landscape. This historical transition in their mode of sustenance allows us to draw a connection between these two spaces regarding resource depletion, agrarian transformation, population mobility, and land and forest policies, which eventually change the community’s relationship with nature. It also shaped their politics of asserting Indigenous identity in the post-colonial period, where the complex co-existence of dwelling nature emerged beyond the materialistic appropriation of land and other natural resources. Thus, Indigenous religious practices in the eastern Himalayas (discussed below) survived through long-drawn conflict over resource sharing in different historical periods, most effectively beginning with the British annexation of these territories. We begin with the Darjeeling Hills.

Darjeeling Hills, which was part of the Sikkimese territories under the Raja of Sikkim, was annexed by the Gorkha kingdom in 1788, a powerful Himalayan kingdom from Nepal. As early as 1771, this Gorkhali Kingdom under Prithvi Narayan Shah aimed to unify Nepal by occupying several smaller principalities ruled by ethnic chieftains. Primarily based on the idea of uniform cultural and religious nationalism (Hindu Nationalism), this kingdom had expanded its territories from Sikkim in the east and the Garhwal region of Uttarakhand in the west. This expansion of the Gorkha kingdom and the growing ascendancy in Nepal worried the British East India Company, which wanted to establish a stronghold over the region. The tension escalated further when the British wanted to control the Terai regions of Nepal, resulting in the famous Anglo-Gurkha War in 1814. The British emerged victorious in the war, and in 1815, the Treaty of Sugauli was signed, in which Nepal had to cede all those territories the Gorkhas had annexed from the Raja of Sikkim to the East India Company. The British returned the land annexed by Nepal to the Raja of Sikkim through the Treaty of Titalia in 1817 and guaranteed Sikkim’s security. Attracted by the cool climatic conditions favourable for the European sanatorium and by its strategic location to command the Himalayan policies, the British wanted the Darjeeling Hills to be under their control. After a long negotiation, the Rajah of Sikkim formally gifted Darjeeling to the British in 1935 through a deed of grant.

As Nepal witnessed a rapid expansion of cultural and religious hegemony under the Hindu ruler, the annexation of Darjeeling by the British opened a new destination for many marginalised ethnic groups from Nepal. The colonisation of the Darjeeling Hills resulted in a large-scale land transformation, where monocropping became the British’s first step towards commercialisation. A crop like tea became a popular species to arrive in the hills and changed the destiny of many communities and the landscape in the Himalayas (

Douglas 2020). The successful cultivation of tea in Darjeeling was enabled by the expansion of scientific knowledge on climate, species, and plantation agriculture (

Tamang 2024), where a new group of populations was encouraged to settle, who would perform the settled occupation in contrast to the shifting cultivation practised by many Indigenous communities like the Lepcha tribes. To escape the rigid caste structure imposed by the state as well as atrocities and land encroachment by the Hindu high caste (

Caplan 1970), many marginalised ethnic groups, such as Rai, Limbu, Tamang, etc. (mostly from eastern Nepal), migrated to the Darjeeling Hills. They became the most reliable labour force for British tea plantations and other sectors.

5 The large-scale establishment of tea plantations, cinchona plantations, and other commercial activities, such as the establishment of the forest department in the 1860s by the British to secure timber supplies for imperial needs (

Guha 1989;

Sivaramakrishnan 1998;

Guha 1989;

Tamang 2022), brought a considerable number of labourers from different parts of the neighbouring countries, mainly from Nepal, and made Darjeeling a melting pot of different ethnic cultures where ‘ethnically diverse settlers found common ground in their Himalayan heritage and the Nepali language became (and remains) Darjeeling’s lingua franca’ (

Middleton and Shneiderman 2018).

While the Nepali language gained prominence, especially in public and social spheres, the 1911 census data also highlight the prevalence of tribal dialects within various communities. Out of a total population of 44,409 Rai, 39,448 were recorded to speak the Khambu dialect; out of 13,804 Limbus, 11,489 spoke Limbu; 26,963 Tamang out of 27,226 spoke the Tamang language; 3511 Sunuwar out of 3820 spoke Sunuwar; and 5150 out of 6927 spoke the Newari language (

Dash 1947). This existence of multiple Indigenous languages gives a hint about the prevalence of multiple cultural and religious practices among these ethnic groups, which was further recognised by recording these groups (mostly Damai, Kami, Sarki, Gurung, Mangar, Tamang, Khas, Limbu, Newar, and Sunuwar) in the 1931 and 1941 census as “Hills tribe” (

Chhetri 2023, p. 63). All these groups actively maintained their cultural and religious practices alongside the growing ascendancy of the Nepali language and Hindu religion

6 (

Tamang 2018) as a “modern identity” (

Golay 2006). The existence of different ethnic associations in Darjeeling Hills during the colonial period (

Chhetri 2023) also provides a testimony to such co-existence of Indigenous culture and religious activities by different ethnic groups. Perhaps Indigenous religious practices were perceived as major challenges to the British missionaries in the hills of the Darjeeling and Kalimpong regions. Interestingly, such Indigenous religious practices were considered “demonolatry” by many European missionaries. Scottish missionary Dr. John Anderson Graham wrote:

“Demonolatry prevails in those mountains among all the races, irrespective of the religious system with which they claim connection. To the aboriginal Lepcha, the rites of religion are chiefly valuable in averting the anger or malice of an evil spirit as shown in the illness of a dear one, and all sickness is caused by such possession.”.

As Indigenous religious practices were largely associated with the idea of “healing”, missionaries in the hills used this notion of “healing” to convert many Indigenous communities into Christianity. Another Scottish missionary, Rev. William Macfarlane, in this context wrote:

“Their sentiments towards the Mission at this time underwent a complete change. At first it was viewed with deep suspicion. Now they began to come daily in twenties and thirties for medicines. We were welcome to their houses and allowed to read and pray where no one would previously have permitted us to enter.”.

Amidst this colonial articulation of Indigenous religions as “demons”, the Nepali language proliferates, along with the Hindu religion, and so does its demand for recognition of Nepali as an official language. Alongside, the demand for Nepali/Gorkha identity grew popular in the Hills, further accentuated by the demand for separate administration for Darjeeling Hills, which started in 1907 only. Notably, to dismantle the growing influence of the Nepali language and its political implication, the 1952 census presented only 19.96% of Darjeeling’s population as Nepali speakers;

7 it was 66% (

Hutt 1997). The state census ‘present[ed] only Kami, Damai, Chettri, Brahmin, and Sarki as Nepali-speaking, while the rest of the hill populace—Limbu, Gurung, Rai, Mangar, Sherpa, Newar, Lepcha, and others whose lingua franca was also Nepali—were counted as separate entities on the grounds of having their own dialects’. Therefore, the politics of indigeneity in the Hills of Darjeeling have a long history of identity conflicts and negotiation with multiple identities that became louder in the post-colonial period with the rise of Gorkha nationalism (

Subba 1992;

Wenner 2013) and the ethnic movement for Scheduled Tribes (ST) status (

Middleton 2015;

Shneiderman and Turin 2006;

Chhetri 2023;

Tamang 2018).

Although colonialism transformed the landscape in Darjeeling from rugged hilly terrain to an Empire’s Garden (

Sharma 2011), it forced many local communities to adapt to a new occupation, curtailed their land rights, destroyed Indigenous sacred sites by reserving the forest for commercial activities, and introduced a new way of life; however, it does not necessarily imply an extreme disconnection of people’s beliefs and connection with the forest or other natural sites. They manifest it in various forms, even without formal rights over land, forests, and other natural resources. The assertion of multiple forms of identities, most notably the recent assertion of tribal identities by different ethnic groups (such as Rai, Gurung, Sunwar, Mangar, etc.) in Darjeeling Hills, provides testimony to such connection where these groups assert their distinct tribal culture, religions, and other practices before the state anthropologists in order to bargain for the Scheduled Tribes (ST) status (

Middleton 2015;

Chhetri 2023). Although orchestrated mainly to appeal to the survey team, such assertion of tribal identity by different ethnic groups in Darjeeling offers a rich Indigenous way of life, their sacred connection to nature, and their long-drawn political struggle to be recognised as “Indigenous”.

On the other hand, Assam had come under the colonial rule of the East India Company after the Treaty of Yandaboo in 1826. The treaty was a watershed moment leading to the downfall of the Ahom Kingdom and the numerous independent tribes of the region. Since the start of the colonial occupation, the population living in the Brahmaputra Valley was brought under a new fiscal regime (

Kar 2019). There was a gradual refashioning of people’s relations with lands and resources. Similar to how the communities in Darjeeling were pushed towards settled occupation, the refashioning was on the virtue of settled agriculture as a marker of civilisation and stable revenue generation (

Baruah 2001;

Kar 2019), which lies in the introduction of the category of

ryot.

Kar (

2019, p. 39) writes about

ryots as “surplus-producing, plough-using, gainful-labouring, sedentary peasants; the

ryots were routinely depicted as the evolutionary winners against the hand-to-mouth, slashing-and-burning, nomadic, almost pre-productive tribes.” Moreover, the

ryots were “touted as the real beneficiaries of civilisational progress under the imperial rule.” Simultaneously, there was an increase in the tea plantation economy on the colonial virtue of converting the unused ‘wastelands’ and the forest spaces to reserve forests for the benefit of colonial rule, denying people’s rights over the forested spaces. Hence, Assam’s forest and ecological history exposes the clash between tribal and peasant communities against the colonial and post-colonial forest departments (

Saikia 2011). For instance, the census enumerators contradict the Mising way of living with the plain Assamese settlement as,

“…where they follow a system of migratory cultivation. Their principal crops are summer rice and mustard, maise and cotton, sown in clearances made by the axe and hoe in the forest or the jungle of reeds. Their villages, usually placed on or near the banks of a river, consist of a few houses built on platforms raised four or five feet above the naked surface of the plain, presenting a strong contrast to the ordinary Assamese village with its orchards of betel, palm, and plantain, and its embowering thicket of bamboos.”

8

The Misings were known to be mobile populations (also see

Mills [1853] 1984, p. 651). According to the Misings’ oral narratives, the amount of land a family owned depended on the number of members in a family, and the family was the production unit. There was no individual possession of land. Possession of land did not pass from one generation to another (

Bhandari 1992). Mising scholars like

Peter Pegu (

2019) assert that Misings did not have the notion of ancestral land. These new policies introduced by the new fiscal regime have greatly influenced the change in land usage, forcing people to a sedentary existence from a mobile existence with increased intensive agriculture and changing relations with lands and forest resources. Hence, there was a refashioning of the landscape, and particularly, there have been changes in the value assigned to land. In the process of the influence of the colonial authorities, people gradually lost their customary rights over the land and forest resources to which they had access. Moreover, the colonial policies of settling mobile populations along a riverine landscape had forced them to suffer from recurring floods, often displacing people and rendering thousands of Misings landless and homeless (

Cremin 2011;

Pegu and Pegu 2018). In addition, the formation of reserved forests as a conservation space since colonial times has forced people to fight and continue to tussle with the Forest Department to claim access to the forest resources until now (

Cremin 2011;

Pegu and Pegu 2018). This backdrop of increasing vulnerability and increased loss of customary rights over resources has led to the tribal autonomy movement in Assam, forming the Tribal League that highlighted and fought for the tribal issues in the region in the pre-independence period (

Pathak 2010).

In post-colonial times, tribal problems regarding the loss of tribal lands and culture remained pertinent for the tribal groups of Assam.

9 The Boros, Misings, Deori, Misings, Tiwa, and Rabha tribes of Assam, which are categorised as Scheduled Tribes, had engaged in autonomy movements demanding Sixth Schedule status, a provision in the constitution of India that grants them rights to control their resources and promote their cultural identity, language, and beliefs. Besides the question of having control over resources and development, the Mising demand for autonomy is based on asserting and preserving their distinct language, culture, and religious traditions against a larger Assamese state dominated by non-tribals.

10 Apart from the Boros attaining Sixth Schedule status, the fight for achieving the Sixth Schedule is an ongoing struggle for the Mising and other plain tribes. These assertions of safeguarding and promoting Indigenous religious practices and traditions bear testimony to promoting their indigeneity by asserting an Indigenous way of life rooted in their cultural and religious practices.

Besides the incoming British colonial regime, the Misings faced the forces of Neo-Vaishnavism, which had been active in the Brahmaputra Valley since the 16th century.

11 Census enumerators noticed the conversion of many tribes of the region to Neo-Vaishnavism under the

Goshains (spiritual leaders), who were the heads of the

sattras.

12 The Misings were documented as a tribe that believed in the propitiation of departed spirits and the reverence of the earth and sun.

13 The

Mibus, who were shamans, played the intermediary role between deities and humans.

14 The

Mibus played an essential role in driving away the evil spirits that impact the well-being of humans. Nevertheless, for the Misings, the influence and conversion to Vaishnavism varied based on their migration and contact with

sattras of the Brahmaputra Valley. The census of Assam 1881 mentions the early Mising settlers in the plains to be more influenced by Vaishnavism and to have taken up rituals related to the new religion and also the deities, where ‘Parmeswar’ and ‘Sankar’ (names of Hindu gods) were reducing their traditional religion and replacing the role of

Mibus to only a few rituals on a household scale.

15 However, the census notes, ‘Whatever the deity, the essentials of worship are the same, consisting of the sacrifice of a fowl, a pig, or, on great occasion, a buffalo, and the drinking of rice beer’.

16 Similarly, despite orders from

Goshains, later census reports indicate that the Misings somehow abandoned the consumption of buffaloes or beef except for fowls, pigs, and alcohol, resisting and negotiating the influence of the new religion (

Allen 1902). Moreover, in the census report of 1931 on Assam, an Assamese census enumerator reports that Misings, although influenced by Neo-Vaishnavism, have always existed independently from the clutches of the

Goshains and from the Assamese caste society, asserting themselves to be different (

Mullan 1932). Hence, the religious practices of the Misings have been refashioned, and they have negotiated with Neo-Vaishnavism.

Nevertheless, despite being influenced by larger religions and the transformation of nature by extractive activities, people remain intact in deifying nature.

Karlsson (

[2011] 2023, p. 16) argues that “…it is not a matter of wholesale transition from one mode to another, but rather a complex co-existence of multiple modes of dwelling, where the capitalist appropriation nevertheless has come to dominate.” Therefore, this deification of nature beyond a materialistic perspective reflects the Indigenous people’s understanding of nature and their existence with nature through various cultural, social, and sacred ways, which we will discuss below through narratives from the field. The brief historical outlook of Darjeeling and Assam certainly provides a glimpse of how Indigenous religious practices were constantly shaped by different powerful forces, evolved, and remain an integral part of the community’s everyday life even in the age of rapid transformation.

3. Everyday Indigenous Religious Practices in the Eastern Himalayas

Among different Indigenous communities in the eastern Himalayas, they believe in the presence of spirits, and they are attributed to various illnesses, healing, well-being, and protection of the community and its local environment. Many colonial writings defined it as a “primitive religion”, prevalent in the form of animistic belief. They mostly associate it with malevolent spirits possessing a fear of demons. Therefore, O’Malley, while describing the religions of Darjeeling, writes:

“Broadly speaking, the Hinduism professed in the district is nothing more than a thin veneer over animistic beliefs. Beneath this veneer, the real popular religion can be seen in the worship paid to a host of spiritual beings whose attributes are ill-defined but whose cheap power is to cause evil to their votaries. The religion prevalent is, in fact, demonolatry, of which exorcism and bloody sacrifices are the most prominent features.”.

We offer a complex picture where different kinds of spirits are clearly distinguished and adopted in their everyday rituals, which are associated with different activities ranging from household to farm, river to forest, mountain and valley, and, more importantly, care and healing.

17 We begin with narratives of benevolent and malevolent spirits encountered in our fieldwork.

A 49-year-old male member of the house, Puran,

18 has been unwell lately, and all the burden of the house falls upon his wife, Sharmila. From the collection of fodder to other household chores, she must bear it all alone, as their son has recently joined the Indian Army, and their daughter is staying in a nearby town to pursue her undergraduate studies. When I reached their home for the fieldwork, she was preparing for rituals with some leaves, eggs, holy water (

choko pani), pieces of black cloth, and needles. Puran looked thinner and paler as compared to my previous visit and was lying quietly in one corner of the room. When I greeted him and asked about his sickness, his wife replied, “Some evil spirit must have hunted him from the jungle while collecting grasses last Sunday”. She continued saying, “

Maila baje (local shaman) will come tonight for his treatment; therefore, we need to be ready with all this stuff (while showing those things mentioned above).” I was curious to know more about it. Still, I asked her if he had visited any doctors. She said she had insisted on visiting a doctor several times, but he refused to travel. “He wanted to meet the

Maila baje first and then go to the doctor later if required”, she continued. I asked them if I could stay back and watch the ritual. She offered me without hesitation, as I had stayed in their place before, also during my PhD fieldwork.

Maila baje, a shaman belonging to the Rai ethnic group, arrived at their home at around 7:00 p.m., and it was already dark outside the house. He asked for all the stuff that he had asked them to prepare, and upon receiving it, he started cleaning the floor near the main door with

choko pani and placed them one by one. He asked Puran to stay on one side of the door and asked him to hold some amount of rice and flowers in his hand. While his wife was busy making a fire outside the home,

Maila baje started chanting

mantras. I closely observed him and tried to understand the language in which he was chanting. Although he was chanting in a language familiar to me, I could barely understand a few words like

Pahad ko devta (mountain deity),

Jungle ko devta (jungle deity),

Khola (river), and

Nala (stream). After some time, he asked for hot water and soaked the bundle of leaves in it before he started beating his body with that. His voice grew louder, and his body shook while he kept talking, smiling, and screaming inside himself. I stayed in one corner of the room, frightened but curious. I looked at the grandfather sitting next to me, and he said, “he has possessed the spirits of local deities.” After almost 10 to 15 min of the unusual alteration of his consciousness, he finally came back to his normal state of consciousness and touched the head of the Puran who was sitting idly next to him and said, “Some negative/evil spirit from the jungle has followed you and stayed in and around you, but I have sent them back. Now you do not have to worry; keep this (he picked up some rice grains from the plate and handed it over to his hand) below your pillow before you sleep.” He told him to offer prayer to a deity who resides in the forest whenever he goes to collect grass or fodder. He said, “You can perhaps offer one red-coloured fowl to the local deities to seek their protection in the forest”. While leaving home, he tells him not to obtain grass from certain trees (he named the trees, which I failed to note) where the local deity resides. When I was preparing to leave their place the following day, Puran was already up from his bed and sitting on his balcony. I asked him how he felt after the ritual, and he replied, “I could sleep peacefully last night”.

Scene 2 from Bélang, Dhemaji, Assam

Context: Pranab K. Pegu witnessed some unnatural deaths in his extended family.

Every family member was concerned about those unnatural deaths. A Mibu was called to find out the reason behind those accidental deaths. Mibu mentioned that one of the dead ancestors was not revered by rituals. The Mibu said he had died as a bachelor and needed to be revered; otherwise, unforeseen deaths are bound to occur. After knowing the reason, their family had performed the ritual in his name with the belief that there would not be any unnatural deaths. Following that, for a better future, and prosperity, and to avoid unnatural deaths, their family called for érang/burté Dobur, a ritual to confess to the wrongdoings committed by adult family members that might have led spirits to detest the actions. In this ritual, one has to speak about wrongdoings in the presence of family members and the Mibu. It is a confession for the family. The ritual is to do away with spirits’ malevolent eyes because of wrongdoings committed by family members.

These two scenes provide a background to establish the significance of “spirit” in Indigenous ritual practices, which are crucial in maintaining their relationship with the local environment. Despite being historically influenced by Neo-vaishnavism, the persistence of the belief in

Uis19 is prevalent among the Mising tribe (

Bhandari 1992;

Mipun 2012).

Uis are omnipresent. It governs every space, be it a house, a farm, a forest, a hill, or a river. Mipun believes that thunder and lightning, water and fire, and earth and air are all abodes of spirits that must be propitiated regularly (

Bhandari 1992;

Mipun 2012). This is evident in many Mising rituals practised in present times, where

apong,

20 fowl, and pigs remain essential in offerings to the spirits and to those Hindu deities that have become integral to religious belief for most of the Mising population.

For the Misings, the stories of

Mibus and their power to drive away evil spirits are still narrated in Mising villages; however,

Mibus are almost non-existent. The decline of

Mibus within the Misings has to be contextualised in the conversion of the Misings by the Neo-Vashnavite satras. In contemporary times, most of the Misings continue to profess religious beliefs related to the Kewalia, Kalhangati, or Nishamalia sect of Neo-Vaishnavism (

Mipun 2012).

21 However,

Mipun (

2012) describes it as a synthetic product of Hinduism and Animism (See also

Taid 2013).

Bhokots22 have replaced the role of the

Mibus. Currently, the majority of Mising engage in the worship of both local spirits and Hindu gods. While many Misings practice a syncretic form of religion, some have chosen to abandon the offerings of alcohol, fowl, and pig to the deities, instead becoming committed followers of Neo-Vaishnavism. Similar is the case with some communities in Darjeeling who have abandoned the offering of alcohol and blood to deities and replaced it with plants, fruits, and other materials, largely influenced by the Hindu rituals. More recently, there has been a notable conversion of Mising to Christianity, who have foregone the reverence of

uis. Nevertheless, this syncretic practice forms the majority of the Mising and some ethnic communities of Nepalis in the Darjeeling Hills who still adhere to the worship of spirits, which they believe govern every aspect of their lives. Although they have been influenced by proselytising religions, their commitment to venerating spirits reflects a deep-rooted belief that spirits govern every aspect of life. The rituals to honour spirits like

uis are an important process in their social reproduction. For instance, socio-economic activities of a large section of the Misings are rooted in venturing in nature, like the forest, the hills, and the rivers. Hence, it is logical to assume that people revere the

uis that govern these spaces. Moreover, worshipping these spirits was also a way to assert tribal identity, particularly in the face of the continuing marginalization, displacement and cultural erasure. Historically, the continuance of the spirit worship is rooted in the assertion of it as an Indigenous religion, part of their assertion of an Indigenous identity.

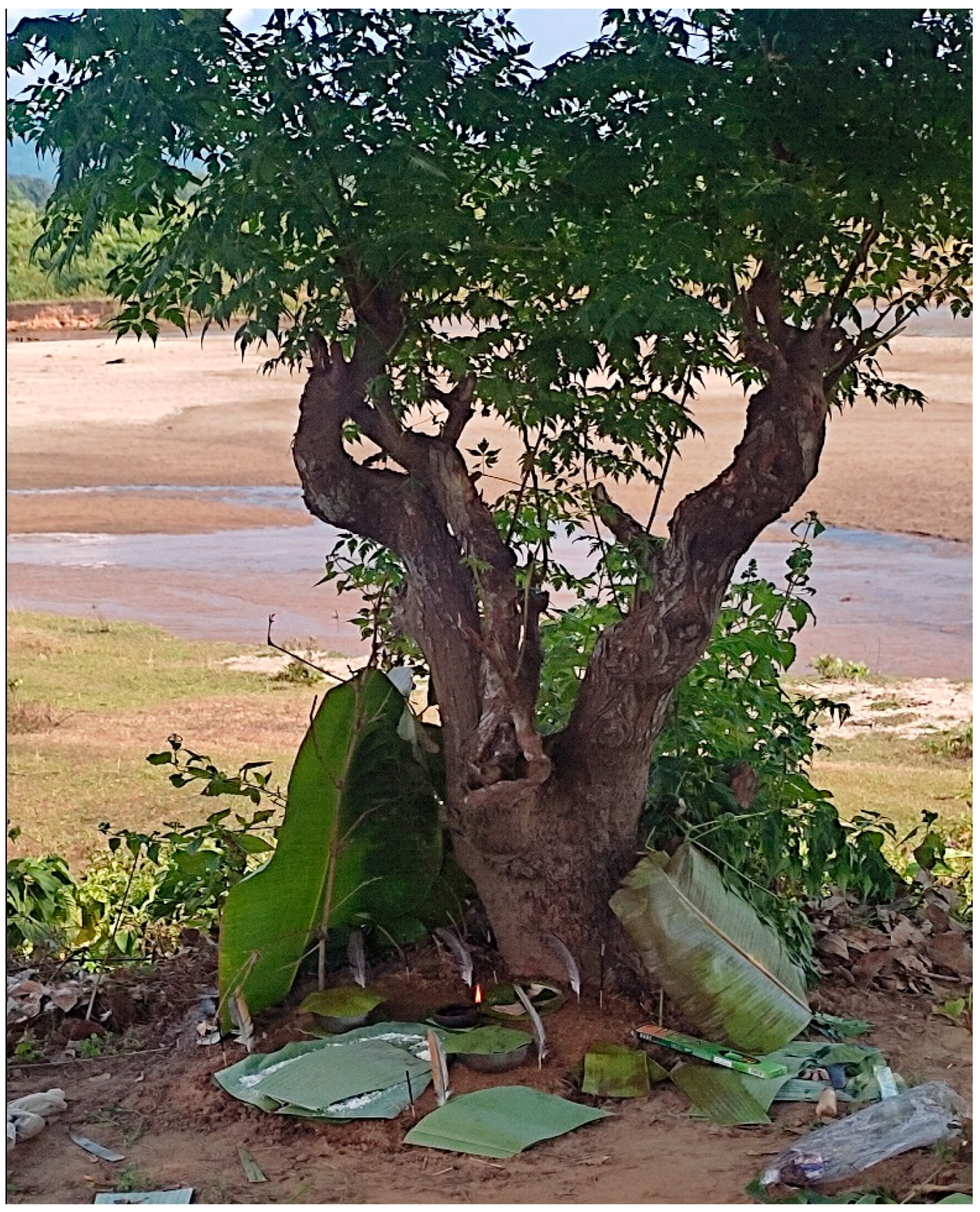

Similarly, among many ethnic groups in the Darjeeling Hills who have their respective

shaman, ritual practitioners believed to possess the ability to embody local deities or spirits, have been declining rapidly in recent times. However, communities have maintained such practices mainly for the sense of security and well-being of families and their local environment. In the Eastern Himalayas, spirits govern every aspect of human life and are attributed to the spirits’ benevolence (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Therefore, one cannot easily ignore the role of spirits in Indigenous religious practices, and Indigenous traditional knowledge about their environment is incomplete without the existence of multiple forms of spirits.

The continuous practices of spirit worship among different Indigenous groups in the Eastern Himalayas reflect a deep relationship with their ancestors, who are often considered guardian spirits. A ritual called

Urom ui is performed by the Mising to worship and hold a big feast, revering the ancestors once every few years. Many communities in Darjeeling also express their relationship with ancestors by worshipping different kinds of spirits. For instance, the Rai, one of the numerically dominant tribes in the Darjeeling Hills, yet to be formally recognised as a Scheduled Tribe, has a tradition of worshipping the hearth (

teen chula or

chula dunga) in their home as a place where they believe their ancestors and deities reside. Almost every ritual, from birth to death, is performed on this sacred

teen chula. These hearths, also called

Samkhalung or ‘ancestor stones’, consist of three main stones representing

Papalung (male ancestors),

Mamalung (female ancestors), and

Ramilung (societal spiritual energies). Although influenced over time by Hinduism and Tibetan Buddhism, the Rai have preserved their distinct rituals, which continue to be observed in their daily lives. “The third stone represents the well-being of society. The Rai priest and priestess,

mangpa and

mangma, conduct the

samkhaling rituals, also known as

chinta, related to household deities praying for the family’s protection”.

23 Moreover, people believe that worshipping ancestral spirits maintains ethical and moral conduct that prevents people from committing misdeeds.

Therefore, morality, security, and healing are part of their religious beliefs, and different communities have their respective ancestral lineages and ritual practices that are undergoing tremendous changes under the influence of larger religions such as Hinduism, Christianity, and Buddhism. However, some scholars argued that “there was never a sharp boundary between local religion and other cosmologies that developed in the Eastern Himalayas, notably, the ones we now call Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam” (

Pachuau and Schendel 2022, p. 119). Although the role of the shamans is now being replaced by Hindu priests (

Bahun in Nepali), Buddhist monks, and

Bhokots24 among Misings, the revering spirit remains persistent in the region. Instead, they have been indigenised with the local deities.

Pachuau and Schendel (

2022, p. 119) further argue that “Local deities embedded themselves in the rituals of these broader religions, and there were constant negotiations about how these related to the gods of these faiths”.

Therefore, the worship of local deities and ancestors heavily shaped the idea of religion in the Eastern Himalayas, in which spirit occupies a central position, and the ritual specialist (shaman) plays a vital role in connecting the human and the world of spirit. This tradition of revering spirits resulted in the nurturing and respect of the local environment by many Indigenous communities in the eastern Himalayas, thereby evoking the sense of harmony and co-existence of multiple species within that local ecosystem. They believed that the spirit resides in trees, plants, rivers, streams, and many other aspects of the natural world and acts as a guardian. These different spirits in the natural world protect the land, forests, and rivers through which the “well-being” of the communities and environment is created in a sacred language. Therefore, pleasing the respective spirits and local deities became an essential aspect of Indigenous religions in the Himalayas.

4. Pleasing the Deities: Nurturing the Local Environment in Indigenous Religions

It was a usual winter day in the field when Rutum invited me to their

Yumrang Ui (rituals to revere the guardian deities of the forest) to have some

apong, which is an alcohol made from fermenting rice with yeast, believed to be sacred, which is offered to deities and food. His family has acquired land in the forest. His family cultivates vegetables and other crops on a small scale. The ritual was held on the plot of land that they possessed. The family’s women were cutting the vegetables to be cooked, and two other women prepared the

apong. Beside them, two middle-aged men were chopping the fowl offered to the

uis. The two local priests were busy overseeing the altar beneath a small tree. The altar offering had pounded rice enclosed by erected chicken feathers (See

Figure 2). While I inquired why they performed the ritual to Rutum, he told me to talk to his father, who was sitting with the others on the spot. While I inquired, “

Baboi (refers to a paternal uncle), why do you do this ritual?” He replies, “Son, you know, we get joint and bone pain yearly; that is when we know the

uis are not happy with us. We work in the forest throughout the year. We might end up doing things disliked by the deities, so we do this ritual every year.” He further says, “Our forefathers and our fathers have done this practice of performing this ritual, and we have followed them.” One of the priests intervened, saying, “People who depend on the hill and work on the hill must do this ritual; otherwise, things might go wrong.” I nodded and asked him, “Do all the

korotiyal do this ritual?”

Korotiyals are people who are involved in petty logging in the hills. People from the area where I did fieldwork have been engaged in petty logging for almost two decades to sustain themselves in the wake of increasing landlessness and fragmentation of land. One replied, “Before they set out to the hills for logging, they offer the rituals to the

uis and leave for work.” The other priest followed up and said, “I was a

korotiyal. I would not go to the hills before I had done the ritual. It gives me confidence in venturing into the hills and protects us from unforeseen accidents”.

“Through the Hills, there are signs of the prevailing fear of demons, such as ‘the little offering in the middle of the path to bar the progress of evil spirits, the living sacrifice being offered to propitiate another, the flattering rice image of a demon supposed to be causing sickness, or the burning of a rag before the door, over which the friends step when they return from burying a relative, to prevent any accompanying spirits from entering with them.”.

Scenes 2 and 3, although contradictory, offer a clear demarcation between humans and spirits in the local environment in which they reside; the fortune of one depends on the well-being of another. Thus, the worship of spirits in various forms is not only confined to the family level but also transcends community and ethnic boundaries. For instance, the rituals of Dobur Ui in Mising villages also function as a ritual to mitigate conflicts between individuals or families. In a recent case in a Mising village, a letter came to the village’s Kébang (village council) seeking permission for a married male member to return who was expelled from the village for eloping with a widow, which led to her death due to some unforeseen circumstances. The death had brought resentment to the woman’s family, leading the man to be denied access to the village. In the letter to the Kébang, there was a special request by the person’s family to let the person continue living in the village. They had particularly mentioned performing Dobur Ui to accept his mistakes and resolve the conflict with the victim’s family. Thus, rituals like Dobur Ui are performed on different scales, from the village scale to the individual scale, in seeking forgiveness for wrongdoings one commits. The village scale does it for the well-being of humans and crops against diseases. Moreover, it is also a ritual where there is conflict resolution among family and individuals against thefts, fights, and any misdeeds that might displease the spirits. Additionally, Dobur Ui is performed for safe passage in the forested landscapes with spirits, particularly for the hunters.

Similarly, in rural parts of Darjeeling Hills, the

devi puja is performed annually to please the gods and goddesses of the “jungle”

25 and to seek their blessing and protection from evil spirits (see

Figure 3). It is generally believed that “the failure to perform

devi puja in time would lead to disappointment of deities that would result in unforeseen consequences/misfortune in the village.” One of the villagers enthusiastically told the author one:

“You know, last year, we failed to conduct devi puja on an auspicious day decided by the shamans, and there was a slight delay in conducting it. Almost all the villagers witnessed a strange tiger roaring from the nearby forest every evening, and people stopped going far into the forest for grass and fodder. We (the elders of the village) decided to conduct the devi puja by consulting our local shamans, and all the villagers contributed cash and kindness to the puja. Upon successful completion of the same on the auspicious date suggested by the shamans, things became normal.”.

(fieldwork in group forest villages, Darjeeling, April 2022)

I asked if “it was a tiger only or if anyone had seen it”, and he said, “It was a spirit who was displeased by some human activities”. The whole village does not eat pork meat in their locality, as they believe that their local deities become angry and make people sick. They collectively acknowledge that spirit dislike will affect human well-being as well as their agricultural field, and in Mising, this process of spirits disliking humans is known as Ka:rag. As the community believed, all these rituals would ease their way into the forest with security. It also gives a sense of confidence to humans venturing into the domain of non-humans.

Thus, the Indigenous spirits’ worship not only acts as a form of repentance and appeasement of the local deities that govern any spaces ranging from the homestead to the farm, rivers, forests, and so on, but also provides a deep sense of well-being for humans and the earth. Therefore, “healing” is an essential element of the Indigenous religion, where different rituals are performed to please local deities associated with different activities. As stated meticulously by Sax in the context of the cult of Bhairav in the Chamoli District of upper Garhwal (Uttarakhand, India), healing rituals are conducted not just to cure illness but also to act as a mechanism to address injustice while tending to social and interpersonal relationships (

Sax 2009). Moreover, Indigenous rituals are temporal–spatial in nature, having specific characteristics associated with different functions that the local environment provides (

Deloria [1973] 2003;

Brahma 2025). A family that depends on agriculture provides rituals for the guardian spirit of the agricultural field. A family whose occupation is based on cattle rearing has some specific rituals to offer to the deities. While this kind of Indigenous ritual has not become a medium for controlling natural resources in a rapidly transforming world, it has provided a numinous space for asserting their rights and affinities with the environment and other species that share the local ecosystem. This lack of political manifestation of such rituals hindered it from advancing into the mainstream of the cultural nationalism perspective on Indigenous knowledge.

Nonetheless, this strong prevalence of “healing” in such rituals connects us to various elements of “nature” that express deep traditional knowledge about the environment, its uses, and its protection. The pragmatic use of different kinds of roots, herbs, animals, and plants in the Himalayas does not simply bear medicinal properties to heal specific illnesses; it is also associated with rituals and ethical guidelines within the local environment. Therefore, the role of multiple spirits in the Indigenous use of natural resources cannot be ignored, and the language of “healing” extends beyond medical assistance to humans and calls for large-scale healing of the local environment, social relationships, different species, and cosmology that they cohabited. Without spirits, the cosmology of many Indigenous communities is incomplete, as they connect life and death with the nurturing of the spirits. Thus, we present our last findings on the spirits of water in the eastern Himalayas, which guide the lifeways of many Indigenous communities.

In October, the river becomes shallow. The river is a few kilometres west of Bélang village. I, accompanied by Gope, a friend, came to one of the islands to meet Torun and his wife, who are involved in fishing and collecting driftwood to sell. These are petty businesses that sustain the people in that region. Just before dinner, Torun had stepped out with his net to catch fish. After 30 min, he returned with almost half a kilogram of small fish caught from his net. While having dinner, we talked about wild elephants crossing the river and destroying makeshift camps on the river’s islands.

There has been news about wild elephants creating problems on these islands. Torun stressed, ‘Elephants come yearly but have not attacked us. The

Ui of the river blesses us. Annually, I do rituals and take blessings from the river guardian deities to protect us.’ After dinner, the couple offered us a space to sleep at their house, but we declined and planned to sleep on the river shore, setting up our tent. We had pitched our tent and were ready to sleep. Unfortunately, I was reminded of wild elephants. Back in my mind, I thought, what if the elephants crossed the river near where we were sleeping? I had a sleepless night, becoming vigilant about elephants. However, Gope was in a deep sleep. Somehow, I had passed the night. After I woke up, I immediately asked him some questions and admitted that I was afraid to sleep because of thinking about wild elephants.

Me: “You know, I could not sleep last night. I stayed awake. However, you slept so well despite knowing about the wild elephants.”

Gope: “You know why? Because my family stays by the river for fishing. Therefore, we offer rituals to the river-dwelling Ui. The ritual has already been done for this year. I am sure the river spirit would protect me from any dangerous situation in the river space.”

Me: “Okay, that is the reason you slept so peacefully.”

Gope: “Even when I thought about the elephants, my trust in the ritual kept me at ease. I was confident.”

(fieldwork by Pranab K. Pegu on one of the islands of Obonori on 30 October 2021)

Like Torun, most Mising family members venture into the river to do rituals to satisfy the guarding spirit of the river. After a few days, I encountered such a ritual on the bank of Obonori. The ceremony was called by three families involved in various river activities. They had brought red-coloured fowl and alcohol (

apong) to offer the spirits. Meanwhile, one of the family members replied when I asked what the significance of the ritual was. She says,

“This ‘Ui’ is performed for well-being while doing activities in the river. It is also a way of thanking the river spirits for granting us enough resources. The ceremony also signifies regrets of actions on the river. The ritual is a way to revere the spirits of the water for allowing us to work flawlessly throughout the year. Moreover, if there are unfortunate events, people believe the deities are unhappy with them.”.

(Group discussion, Obonori, 29 December 2021)

The reverence of the water spirit is common among many other Indigenous groups of the eastern Himalayas (see

Figure 4), like the Lepcha, who define their Indigenous cosmology through rain, snow, mist, and vapour (

Bhutia 2023). Lepcha believed that

Itbu-Moo, the great mother creator, created their world and that different elements of nature, such as rivers, mountains, snow, lakes, birds, dragons, etc., are interwoven. Among many spirits, the water spirit in Lepcha’s cosmology occupies a significant position. Hence, the mountain Kanchenjunga, its snow, and the river Teesta form an important lifeworld for the Lepcha, where different species developed and co-existed through a sacred connection.

“The water dragons, Rong-eet and Rongnyu, originated from the source Kanchenjunga. Along the way, they meet mortals and spirits of all kinds from Mayel Lyang—entities that help each other in nourishing and supporting the circle of life. As the water dragon and the sacred waters follow their path onto the sea, numerous beings and spirits share their life and stories with them.”.

Thus, the Indigenous use of the river was guided by ethical considerations of the river as a life-enabling form that carries in its flow the notion of healing and well-being of different species within the local environment. This contrasts with the materialist use of the river, which tames its water for commercial purposes, as evident in different parts of the world. The rivers in the Eastern Himalayas have also become victims of such hydropower development, and their consequences are far-reaching, as evident in the massive Teesta flood in 2023. However, people still hold practices about river spirits amidst the river’s mechanisation and destruction and are becoming a part of the process. Many Lepcha consider the flood in Teesta due to unpleasant human activities such as building dams in sacred landscapes where different deities reside. In addition, the river’s spirit was not considered while damming the river. This belief in the spirit has made their relationship with nature different from those who see nature as a resource or simply romanticise nature.

Although it sounds like an appeasement of spirits, it is more than that; it also shows the connections between the people who depend on the river. The ritual is a way of reciprocity to the spirit and the river. It is a way to give back to the deities who rule the river. For some, it is a source of confidence in living with the water. The blessings keep them driving and engaging in a very volatile space. The reverence of the spirit does not necessarily mean they do not commodify the river. However, they are also afraid of nature. The relationships between the people and the river are not linear. Various factors influence it, not just one. The people’s relationship with the river is not binary, either revering the river or only commodifying it. The people’s relationship with the river is shaped by the state’s presence, the people’s agency, and the existence of spirits, which play a significant role in the process.

In all these, worshipping different kinds of spirits associated with different deities still orients the Indigenous cosmology that embeds humans into a world of meaning and responsibilities to nurture their local environment more sustainably against the modern extractive development process. This also connects humans to the world of other species and the universe while revering its nurturing role and activities in pleasing different deities. Thus, in a society driven by modern values and profit maximisation, these eco-cosmological beliefs still dictate societal functioning and illuminate a dynamic relationship between humans and nature in the Eastern Himalayas.