Deciphering Arachosian Tribute at Persepolis: Orthopraxy and Regulated Gifts in the Achaemenid Empire

Abstract

1. Introduction

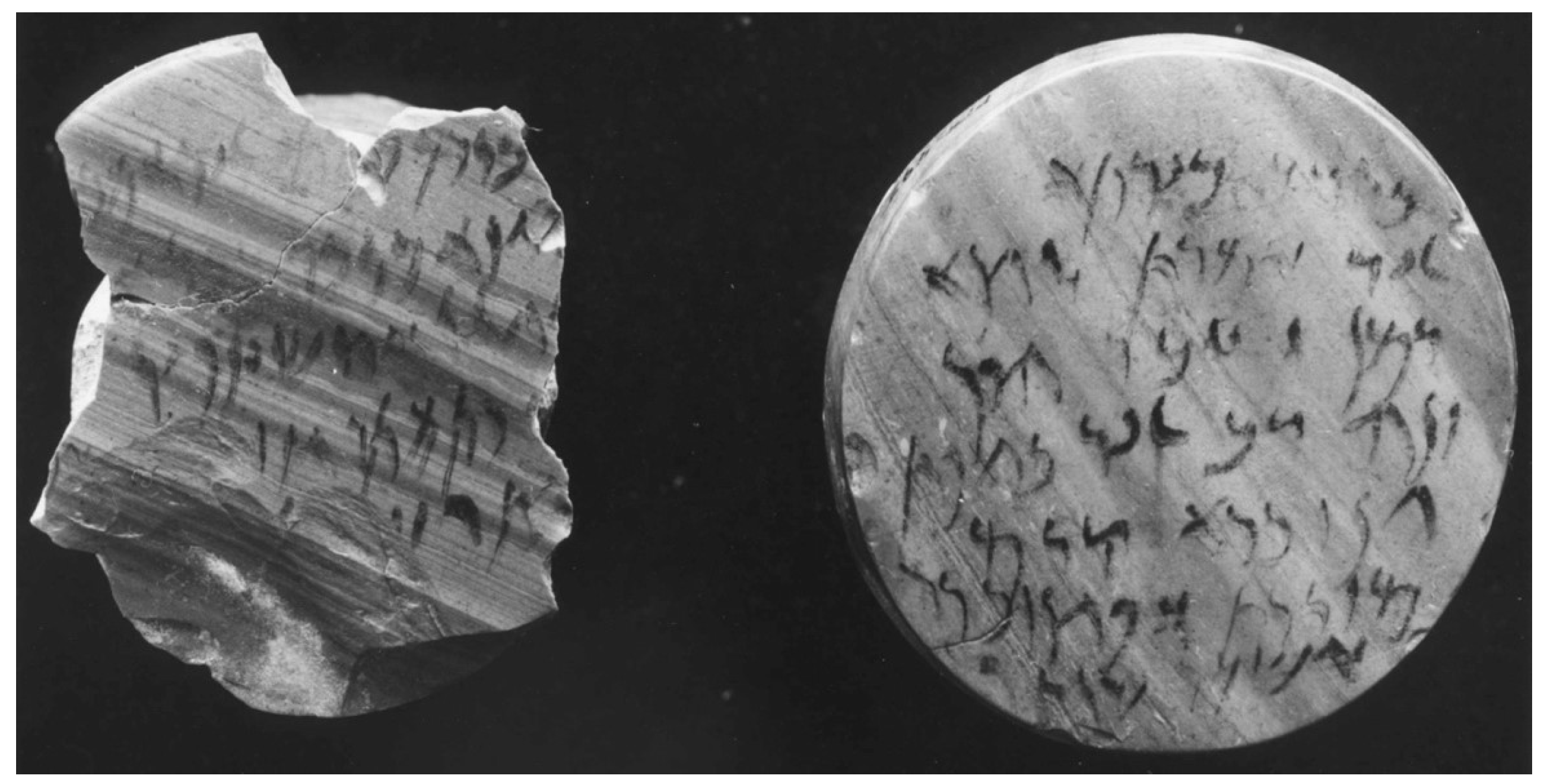

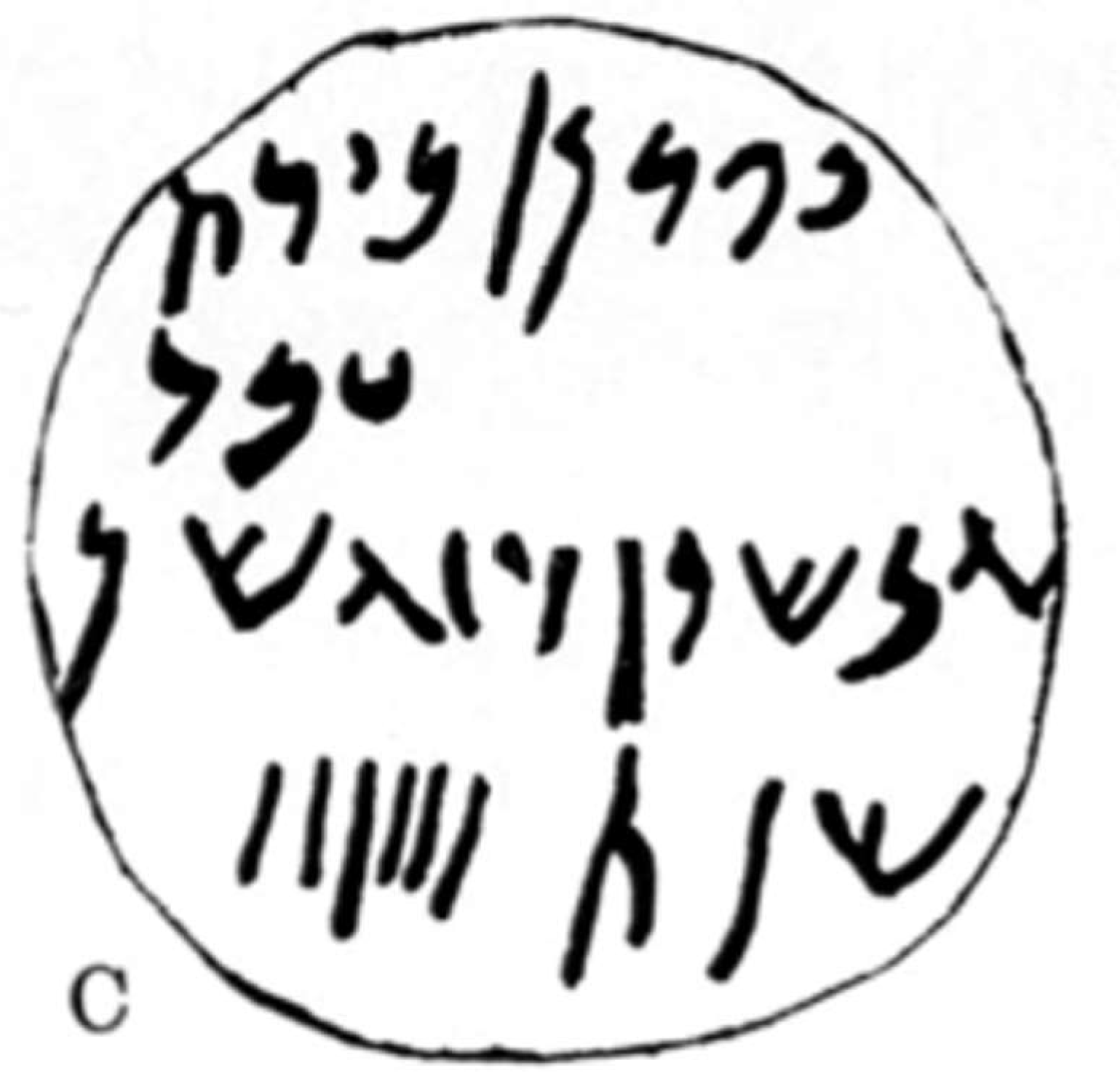

2. Findings and Early Interpretations

- (1)

- The material: green chert, which, as Bernard noted, originates in that province.

- (2)

- A known fortress by the name of Barrikana (*Parikāna) (Tavernier 2007, pp. 389–90) in Arachosia appearing on at least nine6 Persepolis Fortification Tablets corresponding to prkn—providing enough of an anchor to consider the other two names (srk and hst) as place-names denoting fortresses.

- (3)

- The recurring reference to the treasurer “who is in Arachosia” (bhrḥwty).

3. Assessment of Recent Developments

- Nowhere are trays, mortars, and pestles reckoned in ancient sources as “tableware.” They do not figure in the wares represented on the Apadana walls, nor do they appear in the various Greek sources describing the royal table (e.g., Herodotus. Hist. 9.80).8

- Significantly, no precious or “luxury editions” of trays, mortars, and pestles are otherwise known, while it was customary to craft stately variants of royal tableware—including plates (Simpson 2005, p. 108).

- While it can be argued that Achaemenid royal tableware was often made out of silver (or other precious metals) and thus would have conceivably been melted down by looters, tableware made from other materials which would not have been subject to such treatment—such as stone, ceramics, faience, etc., abundantly found in royal residences—would be expected to be unearthed in the treasury hall had it contained a stockpile of precious tableware. Yet not a single one, as Schmidt notes, was found.

- The treasury—at least in Hall 38, where practically all of the PAGC were found—did not store items of intrinsic “transactional” economic value.

- The PAGC should not be classified as “tableware.”

4. A New Look

4.1. Materiality

two sides to materiality. On one side is the brute materiality or “hard physicality” […] of the world’s “material character”; on the other side is the socially and historically situated agency of human beings who, in appropriating this physicality for their purposes, project on it both design and meaning in the conversion of naturally given raw material into the finished forms of artifacts.

4.2. Symbolism of Mazdean Cult

4.3. Philology

4.3.1. lyd and ʿbd

4.3.2. ʾškr

| CC 1 […]◦[…] 2 […]MW inhabitants/those sitting[…] 3 […]ˀNˀ, saying, “I sleep[…] 4 […]◦ in it in Elephantine at night[…] 5 […]◦t ◦◦◦◦◦ 5, which[…] | CV 1 […]◦◦[…] 2 […]⸢f⸣ish to Farna-x◦[(aya)…] 3 […]LH and a house, my iškaru which […] 4 […] Saying Psḥḥnty is before me[…] 5 […]Moreover, said/say[…] |

4.3.3. ʾlp, plg

4.3.4. hwn, ʾbšwn

4.3.5. šmh

5. Administrative Obligation and Cultic Orthopraxy

5.1. The Relation to the Yasna and Mazdean Ritual

5.2. The Formula

5.3. The Process

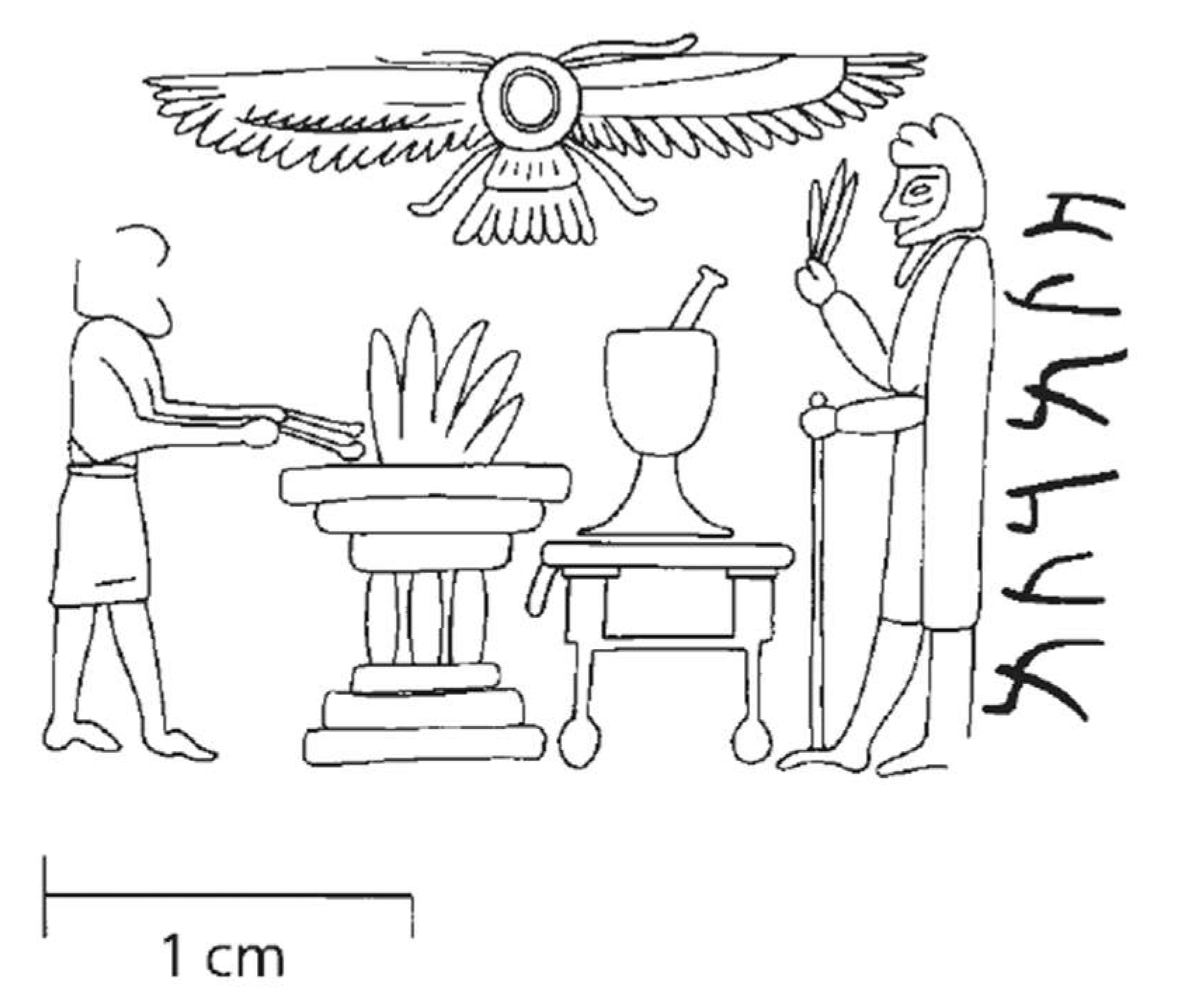

The Mazdean ʾškr-donor would bring his (regular) tax payment to a local fortress (Parikana, Elephantine, and so on). Much like dāta-miϑra, who is probably depicted in the abovementioned seal impression found at Persepolis, he would sponsor a yasna ceremony there in order to show his loyalty, his “orthopraxy,” and rejection of “the Lie”—thus making him cosmically accountable for his truthfulness.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PAGC | Persepolis Aramaic on Green Chert |

| PN | Personal Name |

| TADAE | Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt (Porten and Yardeni 1986–1999) |

| TAO | Textbook of Aramaic Ostraca from Idumea (Porten and Yardeni 2016) |

| CG 62 | Lozachmeur 2006, vol. 1, 229–30 and vol. 2, XXXX |

| DNWSI | Dictionary of the Northwest Semitic Inscriptions (Hoftijzer et al. 1995) |

| CAL | Comprehensive Aramaic Lexicon (Kaufman 1986–) |

| CAD | The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (Gelb et al. 1964–2010) |

| LSJ | Liddell, Scott, and Jones. A Greek–English Lexicon. |

| 1 | These texts are often referred to today, interpretatively, as the “Arachosian texts.” However, a label built exclusively on their objective characteristics—i.e., their findspot, language, and materiality—is preferable. Thus: Persepolis Aramaic on Green Chert (PAGC). |

| 2 | See also Williamson (1991, pp. 41–61). For recent studies, see Henkelman (2017, pp. 102–4); King (2019, pp. 185–99); and Schütze (2021, pp. 405–24). For an evaluation of these recent studies, see Section 3. |

| 3 | An “astonishing number” of identical objects which were reused in the post-Achaemenid period were found in the so-called “fratadara excavations” (Schmidt 1953, p. 56). |

| 4 | The excavations of Persepolis were initiated in 1931 by James H. Breasted, and Ernst Herzfeld became its first field director. Schmidt succeeded him in 1934 (Schmidt 1953, p. 3). |

| 5 | In the earliest report on the PAGC, no interpretation of these objects is given (Schmidt 1939, pp. 61–62). |

| 6 | I thank Wouter Henkelman (personal communication, 16 April 2024) for this information. He also noted that “the contexts connect them explicitly and implicitly with Arachosia.” |

| 7 | This tripod bowl of green chert, found in room 39, is the exception that makes the rule, which caused Schmidt to suggest that it too may have been used for ritualistic purposes (Schmidt 1957, p. 89, pl. 55:3, 56:1). |

| 8 | One could argue that instead of tableware, these utensils represent “kitchenware”. This would only add to the difficulty, since, unlike tableware, there is no documentation that kitchenware held any form of prestige in Achaemenid times. |

| 9 | Though not primarily for the minting of coins (Briant 2002, p. 408). While Herodotus’ passage is highly problematic in its details (see, e.g., Zournatzi 2000, esp. 253–56), it can hardly be denied that imperial economic activity was “silverized” and recurring expenses such as paying soldiers and workers were often conducted in silver (Van der Spek 2011; Kleber 2021a, p. 8; Hoernes 2021, p. 797). It is conceivable that silver tableware may have been melted down to become part of the reserves, which, as it stands, would grow to become legendary, to the point that recent research and metal analyses show that Achaemenid bouillon—in both gold and silver—was the source for “nearly all eastern production, as well as a substantial part of western production, notably in Macedonia” (Blichert-Toft et al. 2022, 64:2). |

| 10 | Transfers of bouillon between economic centers (rather than from an individual to the economic center) are documented, however (Kuhrt 2007, p. 719 [PF 1342: Susa to Matezzish; PF 1357: Babylonia to Persepolis]). |

| 11 | Items made out of these luxury materials are mostly limited to beads and small jewellery (Schmidt 1957, pp. 76–77 [table]). |

| 12 | For an example of such comparanda, see (Westenholz and Stolper 2002, pp. 6–7). |

| 13 | See also critical assessment in Tuplin (1987, p. 139). |

| 14 | The formula lyd+PN is also recorded with a certain ʾwstn—a srkn (“commander, high official”) in a papyrus published by Segal (1983, pp. 25–26, Pl. 2, frg. 9). This ʾwstn served in Egypt in the final decades of the fifth century BCE and was probably related to the (in)famously powerful Ḥananiah, known from the Elephantine documents. For an epigraphic analysis and rationale for the reading of srkn here, see Barnea (2025c). It is also found in certain Idumean ostraca—one of which seems to record the transfer/payment of ʾškr (Porten and Yardeni 2016, p. 48 [A14.3] [henceforth TAO]). |

| 15 | The expression used here in Hebrew is ʾl yd (אל־יד). |

| 16 | The Aramaic expression used here is wʿbdw ʿl (ועבדו על). Additional examples from Elephantine are found in the “Customs Account” (TADAE C3.7). See also Folmer (2021, pp. 266, 275). |

| 17 | Given this consistent evidence, an interesting sidenote is that the use of lyd in ḥylʾ zy lydh made by Aršama in another document (TADAE A6.8) can now be interpreted to mean “the troop that was made over to (=given) him,” rather than “is under his control.” This fits the context of the text particularly well, given that this document deals with a complaint by a frequent associate of Aršama by the name of Psamshek against a person named Armapiya, who appears only in this document. Aršama commands this Armapiya to obey Psamshek henceforth. The contents of the letter therefore also support the notion that Armapiya might be a new appointment who does not yet understand Psamshek’s authority, which needs to be explained to him. |

| 18 | My translation is a correction of the CG 62’s museum edition (https://elephantine.smb.museum/texts/view.php?t=312946 (accessed on 10 June 2025)) with a corrected line 3 of the convex (cv) side. The noun by (בי, “house”) is not in the determined state and should not take the article. Thus, ʾškry seems to be part of a list “and a house, my iškaru”, and so on. I also interpreted the name פרנח(י) as Farna-x(aya) “glory’s partner?” There is room for a yod at the end of the word, but it is broken and might have contained a yod in the broken section. Cf. ʾRthy (TADAE A6.10:10) from *’Rtaxaya (Tavernier 2007, pp. 304–5). |

| 19 | The meaning of Psḥ here is unclear and a discussion as to its possible relation to its cognate known from the Hebrew Bible is outside the scope of this article. I shall treat it is a forthcoming article. |

| 20 | The Old Persian baji and the Elamite baziš also have within their range of meanings the sense of “gifts” or “dues” (Kleber 2021b, p. 134). |

| 21 | The Aramaic text is [פהרברן עבד הון זי גלל זי בז קדם אריוהש אפ[ג]נ[זב]רא ליד ב[גפת גנזברא. |

| 22 | The Aramaic term bz(y) is only recorded in the PAGC. Given the context, I cautiously suggest that it may theoretically be related to the Middle Persian sabz (سبز) for “green, fresh” (also in New Persian)—with an addition of an initial /ś/. While this would correspond to the main feature of these objects, their striking green color, this must remain entirely hypothetical. |

| 23 | |

| 24 | Cf. lengthy study in Folmer (1995, pp. 674–84). |

| 25 | In the vast majority of cases, ancient seals represented their owner (Smith 2018, p. 104). However, even if this seal was owned by someone other than Dātama, what is important for the sake of the study here is that it still represents a non-priestly figure. |

| 26 |

References

- Altheim, Franz. 1951. Review-Persepolis Treasury Tablets by George G. Cameron. Gnomon 23: 187–93. [Google Scholar]

- Amiet, Pierre. 1990. Quelques épaves de la vaisselle royale perse de Suse. In Contribution à l’histoire de l’Iran: Mélanges Offerts à Jean Perrot. Edited by François Vallat. Paris: Éditions Recherche sur les Civilisations, pp. 213–24. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Björn. 2020. Lines in the Sand: Horizons of Real and Imagined Power in Persian Arabia. In The Art of Empire in Achaemenid Persia: Studies in Honour of Margaret Cool Root. Edited by Elspeth R. M. Dusinberre, Mark B. Garrison and Wouter F. M. Henkelman. Achaemenid History XVI. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 565–600. [Google Scholar]

- Barnea, Gad. 2024. P. Berlin 13464, Yahwism and Achaemenid Zoroastrianism at Elephantine. In Yahwism Under the Achaemenid Empire, Prof. Shaul Shaked in Memoriam. Edited by Gad Barnea and Reinhard G. Kratz. In BZAW. Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Barnea, Gad. 2025a. Imitatio Dei, Imitatio Darii: Authority, Assimilation, and Afterlife of the Epilogue of Bīsotūn (DB 4:36–92). Religions 16: 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, Gad. 2025b. The Significance of ṛtācā Brzmniy in Xerxes’ Cultic Reform: A New Light on the “Daiva Inscription” (XPh). Iran and the Caucasus 29: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Barnea, Gad. 2025c. ‘Khnum Is against Us’: The Rise and Fall of Ḥananiah and the Persecution of the Yahwists in Egypt (Ca. 419–404 BCE). Journal of the American Oriental Society, 145. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/128360029/_Khnum_is_against_us_The_Rise_and_Fall_of_%E1%B8%A4ananiah_and_the_Persecution_of_the_Yahwists_in_Egypt_ca_419_404_BCE (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Bernard, Paul. 1972. Les Mortiers Et Pilons Inscrits De Persépolis. Studia Iranica 1: 165–76. [Google Scholar]

- Blichert-Toft, Janne, François de Callataÿ, Philippe Télouk, and Francis Albarède. 2022. Origin and fate of the greatest accumulation of silver in ancient history. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 14: 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogoljubov, Mikhail N. 1973. Aramejskie nadpisi na ritual’nych predmetach iz Persepolja. IAN 32: 172–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, Raymond A. 1970. Aramaic Ritual Texts from Persepolis. University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, vol. 91. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, Raymond A. 1972. The Persepolis Ritual Texts. In The Memorial Volume of the Vth International Congress of Iranian Art & Archaeology, Tehran, Isfahan, Shiraz, 11th–18th April 1968. Edited by Muḥammad Yūsuf Kiyānī and Akbar Tajvidi. Teheran: Ministry of Culture and Arts, pp. 251–57. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, Mary. 1982. A History of Zoroastrianism. Leiden: Brill, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, Mary. 1987. ĀTAŠDĀN. In Encyclopædia Iranica. New York: Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, Mary. 2003. HAOMA ii. THE RITUALS. In Encyclopædia Iranica. New York: Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Briant, Pierre. 1997. Bulletin d’histoire achéménide (BHAch I). Topoi. Orient-Occident. Supplément 1,. Recherches Récentes sur l’Empire Achéménide 1: 5–127. [Google Scholar]

- Briant, Pierre. 2002. From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, Nicholas. 1985. The Treasury at Persepolis: Gift-Giving at the City of the Persians. AJA 89: 373–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, George G. 1948. Persepolis Treasury Tablets. University of Chicago Oriental Institute publications. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, vol. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, George G. 1958. Persepolis Treasury Tablets Old and New. JNES 17: 161–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantera, Alberto. 2017. La liturgie longue en langue avestique dans l’Iran occidental. In Persian Religion in the Achaemenid Period/La Religion Perse à l’époque Achéménide. Edited by Wouter F. M. Henkelman and Céline Redard. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 21–68. [Google Scholar]

- Dandamaev, Muhammad A., Vladimir G. Lukonin, Philip L. Kohl, and Dana J. Dadson. 1989. The Culture and Social Institutions of Ancient Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Degen, Rainer. 1974. Review of Aramaic Ritual Texts from Persepolis, by R. A. Bowman. Bibliotheca Orientalis 31: 124–27. [Google Scholar]

- Delaunay, Jacques A. 1974. À propos des ‘Aramaic Ritual Texts from Persepolis’ de R. A. Bowman. AcIr 2: 193–217. [Google Scholar]

- Diakonoff, Igor M., and Vladimir A. Livshits. 1960. Dokumenti iz Nisi I v. do n.e. (Predvaritel’nie itogi raboti) [Documents from Nisa of the 1st century B.C. (Preliminary Summary of the work)]. Paper presented at 25th International Congress of Orientalists, Moscow, Russia, August 9–16; Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Vostochnoy Literatury [Publishing House of Oriental Literature] (In Russain). [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Samuel. 2021. Greek Conceptualizations of Persian Traditions: Gift-Giving and Friendship in the Persian Empire. The Classical Quarterly 71: 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ephʿal, Israel, and Joseph Naveh. 1996. Aramaic Ostraca of the Fourth Century BC from Idumaea. Jerusalem: Magnes Press. [Google Scholar]

- Folmer, Margaretha L. 1995. The Aramaic Language in the Achaemenid Period: A Study in Linguistic Variation. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Folmer, Margaretha L. 2021. Taxation of Ships and their Cargo in an Aramaic Papyrus from Egypt (TAD C3.7). In Taxation in the Achaemenid Empire. Edited by K. Kleber. In Classica et Orientalia. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 261–300. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, S. K. Mendoza. 2011. Witches, Whores, and Sorcerers. The Concept of Evil in Early Iran. New York: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, Mark B. 2017. The Ritual Landscape at Persepolis: Glyptic Imagery from the Persepolis Fortification and Treasury Archives. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 72. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Gelb, Ignace J., Thorkild Jacobsen, Benno Landsberger, and A. Leo Oppenheim. 1964–2010. The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (CAD). Chicago: The Oriental Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Gershevitch, Ilya. 1974. An Iranianist’s View of the Soma Controversy. In Mémorial Jean de Menasce. Edited by Philippe Gignoux and Aḥmad Tafazzoli. Louvain: Fondation Culturelle Iranienne, pp. 45–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gérard, Collon, and Jean Perrot. 2013. The Palace of Darius at Susa: The Great Royal Residence of Achaemenid Persia. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Gignoux, Philippe. 1972. R. A. Bowman. Aramaic Ritual Texts from Persepolis. RHR 181: 86–87. [Google Scholar]

- Haruta, Seiro. 2013. Aramaic, Parthian, and Middle Persian. In The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Edited by Daniel T. Potts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 779–94. [Google Scholar]

- Henkelman, Wouter F. M. 2017. Imperial Signature and Imperial Paradigm: Achaemenid administrative structure and system across and beyond the Iranian plateau. In Die Verwaltung im Achämenidenreich Imperiale Muster und Strukturen /Administration in the Achaemenid Empire Tracing the Imperial Signature. Edited by Wouter F. M. Henkelman Bruno Jacobs and Matthew W. Stolper. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 45–256. [Google Scholar]

- Henkelman, Wouter F. M. 2021. Local Administration: Persia. In A Companion to the Achaemenid Persian Empire. Edited by Bruno Jacobs and Robert Rollinger. In Blackwell companions to the ancient world. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 881–904. [Google Scholar]

- Henkelman, Wouter F. M. 2023. Irdumartiya and the chiliarchies: The contemporaneity of the Persepolis Fortification and Treasury archives and its implications. In The Persian World and Beyond: Achaemenid and Arsacid Studies in Honour of Bruno Jacobs. Edited by Mark B. Garrison and Wouter F. M. Henkelman. In Melammu Workshops and Monographs. Münster: Zaphon, pp. 235–300. [Google Scholar]

- Hinnells, John R. 1973. Aramaic ritual texts from persepolis. Religion 3: 157–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintze, A. Forthcoming. An Old Persian Formula in the Light of the Avesta. In Studia Philologica, Linguistica, Onomastica Iranica Et Indogermanica in Memoriam Manfred Mayrhofer. Edited by Velizar Sadovski. Wien: Verlag der Oesterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 153–72.

- Hintze, Almut. 2004. On the ritual significance of the Yasna Haptatyhàiti. In Zoroastrian Rituals in Context. Edited by Michael Stausberg. Leiden: Brill, pp. 291–316. [Google Scholar]

- Hintze, Almut. 2022. Yasna. In The Multimedia Yasna Film Encyclopædia. Available online: https://muya.soas.ac.uk/tool/film-multimedia (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Hinz, Walther. 1975. Zu Morsern und Stosseln aus Persepolis. AcIr 2: 371–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hoernes, Matthias. 2021. Royal Coinage. In A Companion to the Achaemenid Persian Empire. Edited by Bruno Jacobs and Robert Rollinger. In Blackwell companions to the ancient world. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 793–814. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, Karl. 1979. Das Avesta in der Persis. In Prolegomena to the Sources on the History of Pre-Islamic Central Asia. Edited by J. Harmatta. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, pp. 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, Karl, Walter B. Henning, Harold W. Bailey, Georg Morgenstierne, and Wolfang Lentz. 1958. Abt. 1, Der Nahe und der Mittlere Osten = The Near and Middle East Bd. 4, Iranistik, Abschn. 1: Linguistik. In Handbuch der Orientalistik. Edited by Bertold Spuler. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hoftijzer, Jacob, Karel Jongeling, Richard C. Steiner, Bezalel Porten, A. Mosak Moshavi, and Charles-F. Jean. 1995. Dictionary of the North-west Semitic inscriptions (DNWSI). 2 vols. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 2012. Toward an ecology of materials. Annual Revue of Anthropology 41: 427–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justi, Ferdinand. 1895. Iranisches Namenbuch. Marburg: N. G. Elwert. [Google Scholar]

- Kamioka, Koji. 1975. Philological Observations on the Aramaic Texts from Persepolis. Orient 11: 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Stephen A. 1986–. The Comprehensive Aramaic Lexicon. Available online: https://cal.huc.edu (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Kent, Roland G. 1950. Old Persian: Grammar, Texts, Lexicon. New Haven: American Oriental Society. [Google Scholar]

- King, Rhyne. 2019. Taxing Achaemenid Arachosia: Evidence from Persepolis. JNES 78: 185–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleber, Kristin. 2021a. Introduction: Taxation in the Achaemenid Empire. In Taxation in the Achaemenid Empire. Edited by Kristin Kleber. In Classica Et Orientalia. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kleber, Kristin. 2021b. Taxation and Fiscal Administration in Babylonia. In Taxation in the Achaemenid Empire. Edited by Kristin Kleber. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 13–152. [Google Scholar]

- Klinkott, Hilmar. 2007. Steuern, Zölle und Tribute im Achaimenidenreich. In Geschenke und Steuern, Zölle und Tribute: Antike Abgabenformen in Anspruch und Wirklichkeit. Edited by Hilmar Klinkott, Sabine Kubisch and Renate Müller-Wollermann. In Culture and History of the Ancient Near East. Leiden: Brill, pp. 263–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kotwal, Firoze M. P., and James W. Boyd. 1991. A Persian Offering the Yasna: A Zoroastrian High Liturgy. Paris: Association pour l’avancement des etudes iraniennes. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhrt, Amélie. 2007. The Persian Empire. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kutscher, Eduard Y. 1954. New Aramaic Texts [Review of E. G. Kraeling The Brooklyn Museum Aramaic Papyri]. Journal of the American Oriental Society 74: 233–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, André, and Hélène Lozachmeur. 1987. Bīrāh/birtā’ en araméen. Syria 64: 261–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, Baruch A. 1972. Review: Aramaic Texts from Persepolis. JAOS 92: 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Bruce. 2021. Religion, Culture, and Politics in Pre-Islamic Iran: Collected Essays. Ancient Iran 14. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberger, James M. 2003. Ancient Aramaic and Hebrew Letters. Atlanta: SBL. [Google Scholar]

- Lozachmeur, Hélène. 2006. La Collection Clermont-Ganneau: Ostraca, Epigraphes sur Jarre, Etiquettes de Bois. Paris: Diffusion de Boccard. [Google Scholar]

- Magdalene, F. Rachel, Bruce Wells, and Cornelia Wunsch. 2010. The Assertory Oath in Neo-Babylonian and Persian Administrative Texts. RIDA 57: 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Modi, Jivanji Jamshedji. 1937. The Religious Ceremonies and Customs of the Parsees, 2nd ed. Bombay: Jehangir B. Karants & sons, vol. pt. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Naveh, Joseph, and Shaul Shaked. 1973. Review: Ritual Texts or Treasury Documents? Review of Aramaic Ritual Texts from Persepolis by Raymond A. Bowman. Orientalia 42: 445–57. [Google Scholar]

- Panaino, Antonio. 2022. Between Semantics and Pragmatics: Origins and Developments in the Meaning of dastgerd. A New Approach to the problem. In Sasanidische Studien. Edited by Shervin Farridnejad and Touraj Daryaee. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, vol. I, pp. 215–42. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, Arthur U. 1957. Persepolis as a ritual city. Archaeology 10: 123–30. [Google Scholar]

- Porten, Bezalel, and Ada Yardeni. 1986–1999. Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt. 4 vols. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University. [Google Scholar]

- Porten, Bezalel, and Ada Yardeni. 2016. Textbook of Aramaic Ostraca from Idumea, Volume 2: Dossiers 11–50: 263 Commodity Chits. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Posener, Georges. 1936. La Première Domination Perse en Egypte. Recueil d’inscriptions Hiéroglyphiques. Le Caire: Institut français d’archéologie orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Redard, Céline. 2022. Cups/Hōm cup/Hōm-urwarām saucer/Metal tray/Mortar/Niche/Paragnā/Pestle/Ring/Ritual table/Saucers/Tray/Tray for bread. In The Multimedia Yasna Film Encyclopædia. Edited by Stefano Damanins, Chiara Grassi, Almut Hintze, Mehrbod Khanizadeh, Martina Palladino and Céline Redard. Online. [Google Scholar]

- Redard, Céline, and Kerman Dadi Daruwalla. 2021. The Gujarati Ritual Directions of the Paragnā, Yasna and Visperad Ceremonies: Transcription, Translation and Glossary of Anklesaria 1888. Corpus Avesticum. Leiden: Brill, vol. 32/2. [Google Scholar]

- Root, Margaret Cool. 1979. The King and Kingship in Achaemenid Art: Essays on the Creation of an Iconography of Empire. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Sancisi-Weerdenburg, Heleen. 1989. Gifts in the Persian Empire. In Le Tribut Dans l’Empire Perse: Actes de La Table Ronde de Paris, 12–13 décembre 1986. Edited by Pierre Briant and Clarisse Herrenschmidt. Paris: Peeters, pp. 129–46. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Erich F. 1939. The Royal Treasury of Persepolis: And Other Discoveries in the Homeland of the Achaemenians. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Erich F. 1957. Persepolis II: Contents of the Treasury and Other Discoveries. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Erich Friedrich. 1953. Persepolis I: Structures, Reliefs, Inscriptions. The University of Chicago, Oriental Institute Publications. Chicago: Chicago University Press, vol. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Schütze, Alexander. 2021. The Aramaic Texts from Arachosia Reconsidered. In Taxation in the Achaemenid Empire. Edited by Kristin Kleber. In Classica Et Orientalia. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 405–24. [Google Scholar]

- Schwiderski, Dirk. 2000. Handbuch Des Nordwestsemitischen Briefformulars: Ein Beitrag Zur Echtheitsfrage Der AramäIschen Briefe Des Esrabuches. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, Judah B. 1972. Raymond A. Bowman: Aramaic ritual texts from Persepolis. (University of Chicago. Oriental Institute Publications, Vol. XCI.) xiii, 195 pp., 36 plates. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970. $25, £11.25. BSOAS 35: 354–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, Judah B. 1983. Aramaic Texts from North Saqqâra, with Some Fragments in Phoenician. London: Egypt Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, St John. 2005. The Royal Table. In Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia. Edited by John Curtis, Nigel Tallis and Béatrice André-Salvini. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 104–11. [Google Scholar]

- Skjærvø, Prods O. 2013. Avesta and Zoroastrianism Under the Achaemenids and Early Sasanians. In The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Edited by Daniel T. Potts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 547–65. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Joanna S. 2018. Authenticity, Seal Recarving, and Authority in the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean. In Seals and Sealing in the Ancient World: Case Studies from the near East, Egypt, the Aegean, and South Asia. Edited by Marta Ameri, Sarah Kielt Costello, Gregg Jamison and Sarah Scott. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 95–124. [Google Scholar]

- Stolper, Matthew W. 2000. Ganzabara. In Encyclopædia Iranica. New York: Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Tavernier, Jan. 2007. Iranica in the Achaemenid Period (ca. 550–330 B.C.): Lexicon of old Iranian Proper Names and Loanwords, Attested in Non-Iranian Texts. Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta. Leuven: Peeters, vol. 158. [Google Scholar]

- Teixidor, Javier. 1974. Bulletin d’épigraphie sémitique. Syria 51: 299–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuplin, Christopher. 1987. The administration of the Achaemenid Empire. In Coinage and Administration in the Athenian and Persian Empires. Edited by Ian Carradice. Oxford: B.A.R. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Spek, Robartus J. 2011. The ‘Silverization’ of the Economy of the Achaemenid and Seleukid Empires and Early Modern China. In The Economies of Hellenistic Societies: Third to First Centuries BC. Edited by Zosia H. Archibald and John K. Davies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 402–20. [Google Scholar]

- Vieugué, Julien. 2014. Use-wear analysis of prehistoric pottery: Methodological contributions from the study of the earliest ceramic vessels in Bulgaria (6100–5500 BC). Journal of Archaeological Science 41: 622–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasmuth, Melanie, and Wouter Henkelman. 2017. Ägypto-Persische Herrscher- und HerrschaftspräSentation in der Achämenidenzeit. Oriens et occidens. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, vol. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Westenholz, Joan Goodnick, and Matthew W. Stolper. 2002. A Stone Jar with Inscriptions of Darius I in Four Languages. Arta 5: 13. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesehöfer, Josef. 2001. GIFT GIVING ii. In Pre-Islamic Persia. In Encyclopædia Iranica. New York: Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, Hugh G. M. 1991. Ezra and Nehemiah in the light of the texts from Persepolis. Bulletin for Biblical Research 1: 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zournatzi, Antigoni. 2000. The Processing of Gold and Silver Tax in the Achaemenid Empire: Herodotus 3.96.2 and the Archeological Realities. Studia Iranica 29: 241–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Object Type | Inscribed | Uninscribed | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortars | 79 | 18 | 97 |

| Pestles | 68 | 12 | 80 |

| Plates | 55 | 30 | 85 |

| Trays | 1 | 6 | 7 |

| Total | 203 | 66 | 269 |

| Header | Shows where the transaction originated and who is its immediate governing authority at the fortress. |

| Body (with the header) | Intended for the accountants at Persepolis and for the ʾškr’s ultimate addressee—the treasurer. It notes the name of the person making the ʾškr donation and who transferred the implement (pestle, mortar, plate, tray, or a combination thereof) to the treasurer, sometimes a description of the object and the regnal year. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barnea, G. Deciphering Arachosian Tribute at Persepolis: Orthopraxy and Regulated Gifts in the Achaemenid Empire. Religions 2025, 16, 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16080965

Barnea G. Deciphering Arachosian Tribute at Persepolis: Orthopraxy and Regulated Gifts in the Achaemenid Empire. Religions. 2025; 16(8):965. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16080965

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarnea, Gad. 2025. "Deciphering Arachosian Tribute at Persepolis: Orthopraxy and Regulated Gifts in the Achaemenid Empire" Religions 16, no. 8: 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16080965

APA StyleBarnea, G. (2025). Deciphering Arachosian Tribute at Persepolis: Orthopraxy and Regulated Gifts in the Achaemenid Empire. Religions, 16(8), 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16080965