Abstract

The rapid secularisation of society has made the work of religious education in Catholic secondary schools increasingly difficult. Contemporary RE teachers are often faced with wildly disparate knowledge and interest levels in their classrooms, to say nothing of their own religiosity. Many systems focus on new curricula, new forms of professional development opportunities, or tertiary courses as a means of enriching what is happening in the classroom. This article examines the approach developed in a small rural diocese in accompanying the RE teachers working in its five secondary schools. It is an accompaniment model that is grounded in the theological and pedagogical insights of Luigi Giussani and adapted to the realities of contemporary education in an Australian setting. The results are a surprising proliferation of enrichment and innovation that can be immediately shared with students in each RE classroom. Moreover, accompaniment offers a more sustainable, agile, and targeted mode of supporting the evangelising work of RE teachers working in Catholic secondary schools.

The precious heritage of the experience gained over the centuries reveals its vitality precisely in the capacity for prudent innovation. And so, now as in the past, the Catholic school must be able to speak for itself effectively and convincingly. It is not merely a question of adaptation, but of missionary thrust, the fundamental duty to evangelize, to go towards men and women wherever they are, so that they may receive the gift of salvation.(Congregation for Catholic Education 1998, §3.)

My speculation for the next forty years of Catholic education is that something has to be done to address the inescapable tension between the high expectations placed on teachers and the capacity of teachers to deliver strong, comprehensive educational RE programs. That teachers can be accompanied to competently teach RE is well within our capacity.(Rymarz 2022, p. 209)

1. Introduction: The Challenges

The Catholic School has its mission. As the opening quote makes plain, the ‘fundamental duty’ of the Catholic school is ‘to evangelise’. This is not a recent addition to the duties of the school. Rather, ‘by its very nature,’ the Catholic school is ‘a place of evangelisation, of authentic apostolate and of pastoral action…’ (Congregation for Catholic Education 1988, §33). In a post-Christian society, however, the point has been made in Vatican documents with increasing urgency. Perhaps, unsurprisingly, it is a point that Pope Francis (2013) emphasised in Evangelii Gaudium—his first major document as Pope:

Catholic schools, which always strive to join their work of education with the explicit proclamation of the Gospel, are a most valuable resource for the evangelization of culture, even in those countries and cities where hostile situations challenge us to greater creativity in our search for suitable methods.(§134)

If the mission is clear—so too are the missionaries. Since the Second Vatican Council, Church documents have been marked by a growing recognition of the vital role played by lay religious educators in the evangelisation of young people in Catholic Schools. In 1982, the Congregation for Catholic education celebrated ‘lay Catholic educators in schools, whether teachers, directors, administrators, or auxiliary staff,’ as both ‘an element of great hope for the Church’ as well as a ‘tremendous evangelical resource’ (Congregation for Catholic Education 1982, §§81, 82). More recently, the document Educating Today and Tomorrow: A Renewing Passion (Congregation for Catholic Education 2014) spoke about the stark realities of the Church’s reliance on lay teachers for her vital work of evangelisation. It acknowledged that ‘Catholic schools are often the only places where young people encounter the bearers of Good News.’ And described the ‘unprecedented situation’ in which religiously pluralistic schools, without priests or religious educators, were completely reliant on ‘the presence of committed lay people, who are well prepared and willing to engage in a very demanding task.’ Alongside this recognition of the lay teacher is the repeated refrain that what is needed is the ‘evangelical identity’ of the teachers in Catholic schools augmented by the requisite training in ‘suitably credible methodologies’ (no. 1, G).

And yet, from the perspective of Catholic secondary schools in rural Australia, a paradox has begun to emerge. The more Vatican documents have called on teachers to open up ‘new prospects of evangelical hope’ (Congregation for Catholic Education 2014, no. 1, G) in their schools, the more empirical research has emerged suggesting that they find themselves either unwilling or ill-equipped to do so. Firstly, there is evidence that many teachers simply do not see themselves as witnesses to the Catholic faith.1 As Sydney’s Archbishop Anthony Fisher summarised the situation in his 2021 Kathleen Burrow lecture: ‘many RE teachers no longer practise the religion themselves and are unacquainted or out of sorts with substantial parts of the doctrine and morals they are charged with teaching…’ (Fisher 2021, para. 19).

Secondly, there is significant evidence that many teachers are lacking both the requisite content knowledge and suitable methodologies for the religious education classroom. In the research conducted by Professor Richard Rymarz, there emerges an undeniable pattern (Rymarz 2007, 2012, 2017; Rymarz and Belmonte 2020; Rymarz and Starkey 2021). He summed up the pattern as follows: ‘There is much published and even more anecdotal evidence that many RE teachers struggle with basic content-knowledge that is germane to teaching RE in a faith-based school context’ (Rymarz 2022, p. 208). And yet, as he added, ‘The most straightforward part of enabling RE teachers to teach well within an educational paradigm is the cognitive aspect. Much of this is to do with improving both the content knowledge of teachers and…their capacity to teach well’ (p. 208).

Moving from the broad picture of RE in Australia to the specifics of rural Australia, we find the same pattern. This article concerns the ongoing work of Secondary School Religious Education in the diocese of Wagga Wagga. A 2017 study by Professor Richard Rymarz commissioned by the diocese, involving thirty-three young teachers of whom 21 were secondary trained, reflected the same interplay of issues. There was a sense of being ‘out of sorts’ with the most fundamental elements of the Catholic faith, accompanied by a difficulty in articulating these same elements. As Rymarz reported, ‘most of the young teachers did not see a link between receiving the sacraments and living a good life’ (2017, p. 16). Instead, they mostly saw religion in terms of personal values meaning that few were convinced about the need for a Church (p. 12). What was particularly evident across the entire study was the difficulty many teachers had in articulating religious ideas. For instance, when asked about God, some spoke of God in purely theistic terms,2 but even those who cited Christian ideas found it challenging. ‘I believe in God... I dunno (sic) I believe the stories about Jesus... it’s hard sometimes but I believe that things happen for a reason and if you believe that, you have to believe in God’ (p. 19). Perhaps unsurprisingly, Rymarz concluded: ‘Although [teachers] were able to relate to and meet the needs of students on a more personal level, that did not feel the same ease [in religious education] when it came to some content areas’ (p. 16). So the question emerges, how can our secondary school lay teachers strive to explicitly and creatively proclaim the Gospel in the religious education provided in our corner of rural Australia?

2. An Accompaniment Model

From the perspective of a diocesan education office, there are no easy solutions to this predicament. Moreover, rural Australia is in the grip of an unprecedented teacher shortage, and religion classes require teachers (Kingsford-Smith et al. 2023). In the quote cited at the beginning of this article, Professor Rymarz, reflecting on the same conundrum posits accompaniment as a practicable solution worthy of consideration: ‘That teachers can be accompanied to competently teach RE is well within our capacity’ (Rymarz 2022, p. 209).

So how do we accompany our secondary RE Teachers? A good place to start is asking teachers what support they would like in the RE classroom. In 2012, Liz Dowling from the Australian Catholic University asked a 123 Australian RE teachers what areas of support were the most relevant to the challenges they encountered in the classroom. Although she was working with Primary teachers, her findings translate to the secondary context. She fitted the responses under four main headings:

- (1)

- Enhancing teacher curriculum supports;

- (2)

- Enhancing teacher pedagogical knowledge for effective practice;

- (3)

- Enhancing teacher content knowledge;

- (4)

- Enhancing professional learning partnerships (Dowling 2012, p. 64).

In short, teachers were asking for support in both the cognitive and the pedagogical aspects of their work. What am I handing over in this class, and what method should I be using? As both Vatican documents and empirical research would suggest this is the profoundest challenge of contemporary religious education as experienced by the classroom teacher.

The question then becomes—how might a small rural diocesan education office meaningfully accompany the eighty religion teachers working across its five high schools? A limited and somewhat fugacious workforce3 in most diocesan education offices has made meaningful and long-term accompaniment a difficult enterprise. Traditionally, systems have favoured expensive and shorter-term projects such as investing in the development of a new curriculum, providing a cavalcade of external (and even international) professional learning opportunities, and insisting on mandatory post-grad study for all religion teachers.4 While a new curriculum might enhance ‘teacher curriculum supports,’ it offers little for the teacher looking for content or pedagogical knowledge. And while professional learning can prove very helpful in that regard, the teacher shortage makes it completely impractical in a rural setting. Similarly, tertiary education can prove very helpful; however, the ability of a traditional Grad-Cert to instil all the requisite content and pedagogical knowledge across only four units is highly unlikely. As Dowling’s research demonstrated, a course which introduces students to the content is often dismissed as being pedagogically impractical. She cites the following quote as being representative: ‘…I am currently completing the Graduate Certificate of RE; I feel the course would be better if it were directed more at teaching rather than academic content. It has not equipped me enough to teach Prep/1 students in an effective way…’ (Dowling 2012, p. 62). And yet, an exclusively pedagogical emphasis is obviously going to struggle to communicate an overview of the Christian proposal, which the teachers are tasked with handing over. Once more we find ourselves back with Lenin’s famous question—what is to be done?

3. Father Luigi Giussani

For Wagga’s ‘Evangelisation and Religious Education Team,’ discovering Luigi Giussani’s extended essay The Risk of Education in 2019 was what the Italian priest would call an event!5 Here was someone who had experienced the challenge of contemporary religious education within an increasingly secularising culture and, what is more important, could articulate a meaningful response. As the then Cardinal Ratzinger put it at Giussani’s funeral, ‘[Giussani] understood that Christianity is not an intellectual system, a collection of dogmas, or moralism. Christianity is …an encounter, a love story; …an event’ (Ratzinger 2004, p. 685). Giussani spent a lifetime facilitating opportunities for young people to encounter Jesus Christ in a religious education which somehow became a global movement—Communion and Liberation. And while many are familiar with that movement, not enough realise that Giussani’s charism was fundamentally pedagogical.

Giussani’s work emerged from an argument with a group of young people on a train in 1958. Although he was shocked by their ignorance and opposition to Christianity, he quickly intuited that it was a question of pedagogy; ‘a matter of method’ (Beria di Argentine 2021).

[E]ither one has to conclude that Christianity had lost all its persuasive power and relevance for the lives of young students, or else one had to conclude that the Christian fact was not being presented or offered to them in an adequate way.(Giussani 2019, p. 4)

Provoked by the contretemps he asked and was granted permission to exchange teaching theology at the prestigious Venegono Seminary for teaching religion at Berchet Classical High School in Milan. On the first day of school in October of 1954, Giussani walked up the front steps of the school, ‘with my heart brimming with the thought that Christ is everything for the life of man…’ (Savorana 2018, p. 168). He described his subsequent experience in the classroom in terms that many contemporary teachers find relatable: ‘it was like going into somebody else’s house, unwanted and uninvited…Every class was like hand-to-hand combat with a bayonet…’ (p. 175). And yet he would persist in this work in order to develop more suitable methods.

For Giussani, the experiences in the religious education classroom would prove definitive. Time and time again, he would link whatever he was working on back to the intuitions formed in those first classes at Berchet (p. 363). He would describe his entire life’s work as ‘all the flux of words, all the river of works that began from that first moment at Berchet high school’ (p. 827). His most famous work was the PerCorso trilogy, comprising The Religious Sense, At the Origin of the Christian Claim, and Why the Church? And yet he argued that these books were merely a continuation of ‘the entire discourse I began at Berchet high school in Milan, right from that first year’ (Giussani, cited in Savorana 2018, pp. 1005–6).

It is precisely this grounding in the practical realities of the high school classroom that makes Giussani’s writing so persuasive and insightful for contemporary religious educators. To read his books is to encounter one who has walked the road we are walking and can therefore fully articulate everything that we have only half-intuited. Since that initial encounter, Giussani’s thought has come to define our model of accompaniment for secondary religion teachers in the Wagga Diocese as we undertake our project of revitalisation in pursuit of more creative and effective methods in the RE classroom.

4. PerCorso as Conceptual Architecture

One of the first things we discovered was that a close study of Giussani’s PerCorso Trilogy suggests a series of curriculum supports that can significantly enhance the coherence of the religious education course we offer in our secondary schools. Moreover, these supports have the capacity to increase the confidence of our teachers charged with delivering that course to their students.

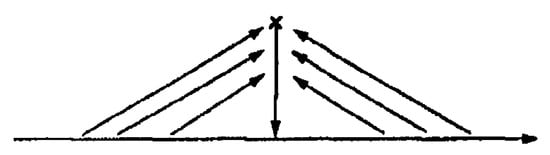

However, let us first take a cursory glance at the Trilogy in order to appreciate its value for the contemporary classroom. Giussani’s teaching in secondary RE always followed a simple outline, ‘God, Christ, the Church’ (Savorana 2018, p. 219). This obviously became the three books. In the editor’s note to the Italian edition, Sante Bagnoli made it clear that the fundamental elements were all a product of his high school religion lessons. One of the methods he would use would be to trace on the board a simple diagram (Figure 1), which he would term the ‘human trajectory diagram’ (Rivero 2011).

Figure 1.

Giussani’s Human Trajectory Drama.

Giussani (1998) explained the diagram in vol II—At the Origin of the Christian Claim. ‘The horizontal line represents the trajectory of human history, above which looms the presence of an x: destiny, fate, the ultimate something, mystery, “God”’ (p. 29). The Christian claim is simply that this mystery, this enigmatic presence we encounter by virtue of our encounter with reality, has ‘become a “Fact” incarnate in our midst’ (p. 29). Through this incarnation we are offered the ‘companionship of God’ (Giussani 2005). But it is a companionship that is lived a certain way. In Why the Church?, he explains that ‘the Church offers herself as the continuity of Christ’ (Giussani 2001, p. ix). She is the bearer of the mystery, offering the companionship of God to all nations. What is crucial for our purposes is that every single concept encountered within a Catholic religious education curriculum can be placed under one of these three headings and when we do so, a distinct order of content emerges.

Giussani argues that because the Christian claim presents itself as the entire solution to our being, ‘we must place ourselves advantageously in order to attain a conviction’ (Giussani 1998, p. 38). Thus, he argues that we must face the Christian fact as a whole—a single proposal. ‘We cannot come to grips with the event if we are not ready to be provoked by its totality’ (Giussani 1998, p. 39). The perennial temptation is to choose a part over the whole, to compare aspects but never hand over the total claim. Giussani, borrowing a phrase from his friend Hans urs von Balthasar, describes this as ‘being stingy with the meaning’ (Giussani 1998, p. 39). Such a fragmentary approach is a betrayal of the students’ freedom because it robs them of the opportunity of seeing the entire proposal and generating a meaningful response.

In contrast, Giussani (1997) argues in The Religious Sense that coherence is what fuels our reason, the dynamism of our being in reality. ‘Coherence is the energy with which man takes hold of himself and adheres, “fastens on” to what reason lets him see’ (p. 129). Without coherence, the student is incapable of genuinely encountering the Christian claim, seeing it whole and unmistakable, and responding in freedom. Indeed, we might say, the evangelising dynamism of religious education then consists in enabling students to perceive and then freely respond to the totality of the Christian claim. The work of Luigi Giussani provides a conceptual structure capable of restoring the indispensable coherence to our work of religious education.6

In the Wagga Diocese, our schools follow a curriculum known as Sharing our Story (Diocese of Wagga 2009). The seven to ten portion of the curriculum gave teachers between six and eight units to cover each year. But there was no set order of units. Thus, students’ attention was moved quickly from topics as disparate as “Mary and the Saints” to “Meaning in the Media/Religion and Ethics” (p. 110). The result was a conceptual incoherence that prevented students from ever really perceiving, much less responding to, the whole proposal across any given year, to say nothing of the entire course.7

A review of the diocese’s Secondary School RE curriculum began in 2023. The committee soon realised that each of the major concepts within the curriculum could be placed under three headings of the PerCorso trilogy. Moreover, by identifying the core concepts from each unit, gaps and repetitions emerged. It then became possible to reduce the number of units to four per year (or one per ten-week term) and create a set order of units for the Diocese. Under the new sequence of learning, the ideas encountered across each year follow the PerCorso Trilogy, the result being that teachers are in a better position to hand over to students a consistent and meaningful proposal that deepens over time.

Each year begins with a topic that is related to the religious sense. For instance, in the first unit of Year Seven, students used to begin with a unit on the sacraments of initiation. Many of our secondary students come to us from government schools and have never before been in a religion classroom. Unsure about the existence of God, they struggled to make sense of what a sacrament might be. Now our Year Seven students begin secondary school RE with a unit called The Religious Sense, which is an amalgamation of two existing units on the human person’s search for meaning and the religious genius revealed in that search.8 Such a unit immediately foregrounds the connection between the students’ experience of reality, their own web of needs, desires, expectations, and questions to which they themselves cannot provide an adequate solution, and the near-universal phenomenon of religion (Giussani 1997, p. 45). The goal of the unit is that students of all backgrounds will have an opportunity to consider the relevance of religion—a subject that will form such an enduring part of their high school education. Moreover, Giussani gives us the means of deepening what we mean by relevance. The word stems from the Latin relevare, to lighten or to comfort. Giussani’s approach transforms the subject from a purely academic exercise to one which is also profoundly contemplative.

Giussani’s writings suggest how we might create the conditions under which students can explore their experience of reality; their deep attraction to reality and their intuition of what Giussani terms their ‘original dependence’ (Giussani 1997, p. 102).9 Hitherto, the emphasis has often been on the unique external socio-cultural experience of each student and what has been called ‘individual meaning making’ (Lacey et al. 2022, p. 96). The result has been one of conceptual fragmentation rendering the pivot to Christian revelation in subsequent units somewhat capricious. Why should we study the miracles of Jesus if we have just established that only two people in the class consider themselves Christian? In contrast, to begin with the religious sense is to begin with what is most fundamental to each student—‘the original element present in all of us’ (Giussani 2019, p. xxvii). And while this is expressed in a multitude of ways, it is also the same for each student (Giussani 2019, p. xxvii). What is interesting is that this lived metaphysics becomes a source of deep unity in an otherwise hyper-pluralistic classroom.10 But also, it rescues the educational enterprise from a narrow and suffocating rationalism, enabling it to move beyond purely speculative enquiries and the mere accumulation of information. Suddenly there is a space for contemplation, veneration, even entreaty.11 To begin with these kinds of units develops a shared relevance that, according to our teachers, has long been missing from our classrooms.

Moreover, the religious sense opens the door to the Christian claim. We no longer study Religion ‘because we are a Catholic School, and it is simply part of who we are’—an argument that renders the claims of religious education arbitrary and therefore mute. Now we study religion because ‘Christ proposes himself as the answer to what “I” am and only an attentive, tender, and impassioned awareness of my own self can make me open’ (Giussani 1998, p. 6). The religious sense, which reaches out towards mystery, has received an answer. As Giussani (1998) put it:

The Christian message is this: a man who ate, walked, and lived the normal life of a man proclaimed: “I am your destiny,” “I am he of whom the whole Cosmos is made.”… [the] joy of every heart and the answer to all its yearnings.(p. 35)

Our students are very free to reject that claim as being untrue, but they cannot be apathetic; they cannot dismiss it as irrelevant to their existence or somehow uninteresting. Every student, regardless of their background, is implicated, by virtue of their humanity, in our common inquiry into the mystery of Jesus Christ. Giussani argues again and again that the incarnation, by its very definition, is of universal significance.

If [the incarnation] did happen, this would be the only path to follow, not because the others are false, but because God would have charted it. The mystery would have presented itself as a historical fact from which no one who had seriously and sincerely faced it could dissociate himself without denying his own path. By accepting and travelling this pathway traced by God, man would become aware that this road, when compared with others, proves to be a more human synthesis, a more complete way of valuing the factors at play.(Giussani 1998, p. 30)

To receive a religious education in a Catholic school is to walk along this road as a classroom community.

The middle terms of each year are now concerned with the Christian claim. However, Giussani’s writing challenges us to re-orient our focus to what is essential—the person of Jesus Christ; his identity and mission. So many of our units were focussed on the historical and sociological details surrounding the Gospel accounts rather than their essential message. Such an academic focus allowed for a more neutral tone among our religiously diverse classrooms. However, it also elided and, at times, even directly obscured the person of Jesus Christ. For instance, a Year Seven unit on the life and times of Jesus might look at daily life in ancient Israel, the various political and religious groups of the time, popular attitudes towards the poor and oppressed and then, time permitting, look closely at one or two Gospel events. These historical and sociological considerations are doubtless interesting. However, their connection with the lived experience of contemporary students is by no means obvious. Consequently, religion class often appeared to be the dissemination and movement of information from one form to another rather than an encounter with a person bearing a proposal for my life.

Now the goal is to look squarely at the person of Jesus Christ as he reveals himself to us in the Gospels. Giussani wrote ‘We must face [the object of our study] in its totality and ask ourselves: “Is it plausible? Is it convincing?” Any other method would evade the object’ (Giussani 1998, p. 38). In other words, we need what Balthasar termed ‘the art of total vision’ (Giussani 1998, p. 41). The goal is to move from isolated events to an appreciation of the whole. To walk ‘the road of knowing’ walked by his disciples, to repeatedly ask ourselves ‘who is this man?’ ‘What are we being shown here?’ ‘What would it mean for our lives if this were true?’12

Finally, each year concludes with a unit on “Living our Companionship with God.” These are units on the Church, the sacraments and Christian morality. In Year Seven we now conclude the year with the unit on the sacraments of initiation. By placing the unit at the end of the year, students have a better chance of understanding why someone might choose to be baptised and what that means for the individual in their life.

In many of our existing units, the Church has been viewed as a purely socio-cultural phenomenon. In the final book of the PerCorso Trilogy, Why the Church? (Giussani 2001), Giussani presents a less-secularised ecclesiology. ‘The Church offers herself as the continuity of Christ’ (p. ix). She is the bearer of the mystery, offering the companionship of God to all nations. Giussani argues that because of her relationship with Jesus Christ, the Church is defined as a sociologically identifiable community, invested with a strength from on high and capable of an entirely new type of life. To teach about the Church is not to analyse a purely historical or sociological phenomenon; it is to show the miracle of grace working in the midst of history and society. ‘…what more exceptional, more wondrous miracle can there be than all of the people who would come later and who would perpetuate the recognition of Jesus in the event of his Church!’ (Giussani 2001, p. 94).

For the sake of brevity, let us restrict ourselves to one example. Jesus repeatedly heals lepers in the Gospel. Moreover, when he sends out the twelve, he explicitly instructs them that they are to follow in his example and ‘clean those who have leprosy.’ (Matthew 10:8) This instruction was taken very seriously. When St Gregory of Nazianzus gave a funeral oration for his friend and fellow bishop, St Basil of Caesarea, he lauded the way in which Basil treasured ‘the imitation of Christ, cleansing leprosy not by word but in deed.’ He notes that formerly, ‘the terrible and pitiable spectacle of men who are living corpses, dead in most of their limbs, driven away from their cities and homes’ was simply considered an insoluble problem. But now there was an example of personally embracing lepers that, in time, became a hospital, ‘the new city’, in which the sick, including lepers, are personally cared for (Gregory of Nazienzen 1953, p. 81). But Gregory is clear that in all that he did, Basil was invested with a power from on high. He talks about Basil’s ‘close communion with the Spirit’ and the way that in all difficulties he would ‘refer all things to the Spirit’ (pp. 63, 77). The question we can consider as a class is, how was Basil led towards a radically counter-cultural life that somehow changed the world and yielded a reality from which grew what we recognise as the modern hospital? For Giussani, the miracle is the way in which the Spirit-filled Jesus is somehow imperfectly present in St Basil and countless others. In the Middle Ages, there was St Elizabeth of Hungry and her great-niece St Elizabeth of Portugal who both founded hospitals and personally cared for lepers. In the 19th and 20th centuries, there was Fr Damien of Molokai, Fr Louis Lambert Conrady in Hong Kong, Mother Teresa in India, John Bradburne in Zimbabwe and Fr. Gaetano Nicosia in Macau. And of course, the countless men and women who worked in Catholic institutions to care for lepers. Giussani would have us consider the words of Mahatma Gandhi, who wrote: ‘The political and journalistic world can boast of very few heroes who compare with Father Damien of Molokai. The Catholic Church, on the contrary, counts by the thousands those who after the example of Fr. Damien have devoted themselves to the victims of leprosy. It is worthwhile to look for the sources of such heroism’ (cited in de Volder 2010, p. 167). To study the Church then is to study the sources of such heroism. To see the unity of her moral triumphs, the unity of life that she offers people and the unity of holiness, which is expressed in an infinite variety of ways, always working through deeply flawed human beings. Giussani sums it all up when he writes: ‘The Church is a life…it is a life of One, the mystery of the person in Christ’ (Giussani 2001, p. 177). In their religious education, our students are given the time and space to examine the Church as the Body of Christ, accompanying it through its history and contemplating the miracle of grace at work in each chaotic generation.

For Giussani, just as Christ reveals himself by signs, so too must the Church. And, as with Jesus’ signs, these miracles, ‘events’ or ‘motions’, are ‘matters of fact’ capable of ‘calling created man back to his Destiny, to Christ, to the living God’ (Giussani 2001, p. 219). Therefore, the work of the religious educator is to examine these signs—to let the students witness the miracle(s) of the Church by walking the road of knowing with Christ through the long history of his Church.13 History and sociology certainly play a role; they help the student see but they are not ends in themselves. The encounter is always with Christ at work in the heart of each person.

By connecting these three movements across every year of study, teachers, and subsequently students, are better placed to make connections between units. The Christo-centric nature of Giussani’s educational proposal reasserts the fundamental centrepiece of religious education. Jesus Christ is the real source of coherence within the subject. This is what Giussani, citing von Balthasar, called ‘the art of total vision’—the understanding of how each concept gains its meaning via its relationship to the person of Jesus Christ. (Giussani 1998, p. 41).

Such a Christocentric reorientation is something long demanded by the Church documents. In Australia, the National Catholic Education Commission’s framing paper makes plain: ‘the development of students’ knowledge and understandings of Christianity’ in Religious Education takes place ‘in the light of Jesus and the Gospel’ (National Catholic Education Commission 2018, p. 7). The identity and mission of Jesus Christ is the core vision of religious education. Where Giussani speaks pedagogically, St Paul spoke theologically when he said that in everything Christ must be pre-eminent (Colossians 1:18). The Art of Vision is merely the methodology of this pre-eminence within a classroom setting in a Catholic high school. Or, to put it in more recent parlance: ‘The proclamation of the Gospel means presenting Christ, then everything else in reference to him’ (Pontifical Council for Promoting the New Evangelisation 2020, §169).

Such clarity of vision has the added benefit of informing the decluttering of curriculum documentation and making those same documents more navigable. If there are learning sequences that simply cannot be connected to the person of Jesus Christ, it is not obvious why they should remain in the curriculum. Moreover, teachers are now much clearer in terms of where the emphasis should be in their lesson delivery. In Australia, a student’s secondary religious education begins in Year Seven and ends in Year Twelve. A Giussanian-informed approach to the proposal contained in that education can be expressed in the simple question: “Jesus Christ, yes or no?” (Giussani 1998, p. 33, cf. 2 Corinthians 1:18–20).

5. Giussani Provides a Method

Luigi Giussani’s biographer, Alberto Savorana, has observed that ‘“Method” is a key word recurring again and again all along the path of Giussani’s life’ (Savorana 2018, pp. 36–37). For Giussani, Christianity had not ceased to be of interest within a secular milieu; rather, secularism, by its very nature, demanded that Christianity be proposed anew. The more we have read of Luigi Giussani’s writings and investigated his own methodology as a teacher, the more confident we have become that he provides a method and in so doing ‘enhances teacher pedagogical knowledge for effective practice’ (Dowling 2012). He does this by virtue of the pedagogical principles he establishes in his writings and by his own teaching methods. For the sake of space, let us look at his understanding of student freedom before examining recollections of his students and then look at how this has yielded creative and suitable pedagogical methods for our secondary RE classrooms.

In The Risk of Education, Giussani emphatically demonstrates that to communicate a tradition—an “explanatory hypothesis of reality”—is to honour the freedom of the student (Giussani 2019, p. 28). This assertion challenges much of the thinking in contemporary religious education. The pluralism of our classrooms has led many teachers to consider a consistent focus on the Catholic tradition as being not only anachronistic but offensively hegemonic—far better to simply let students share their existing opinions on the big questions and work to ensure that the classroom is a place of neutral and respectful dialogue. Indeed, it is often argued that such a religious education is the most meaningful preparation for students living in our pluralistic 21st century.14

Savorana’s biography of Giussani reveals that this is by no means a recent debate. When Giussani first entered the classroom, the work of Guido Calogero15 was proving hugely influential within Italian schools. It had become a common axiom that ‘the secular school was the school of discussion’ (Savorana 2018, p. 238). In contrast, Giussani argued that such a position is an offence against the freedom of the student because it imprisons them in their own half-digested and largely axiomatic preconceptions.16 To refuse to hand over a tradition is to provide an education in scepticism because everything about the classroom proposal suggests that there are only fragments and nothing that can possibly give them an ordered meaning (Giussani 2019, p. 38).

If no proposal is made of a privileged working hypothesis, young people will invent one for themselves, in a convoluted way, or else become sceptical. And scepticism is the far easier route, because there they can avoid making even the effort necessary to consistently apply whichever hypothesis they choose.(Giussani 2019, p. 41)

Moreover, if students are simply called to share perspectives, they ‘forget the need to submit their own ideas and convictions to the test of experience and life. What is lacking is a serious verification of the truth of a hypothesis’ (Savorana 2018, p. 238, cf.; Giussani 2019, p. 41).

In contrast, Giussani enjoins us to create an opportunity for students to look at the Christian event with simplicity and in so doing encounter the dynamism of a truly generative thought growing out into a living tradition and then respond in freedom. Thus, he began his first lesson at Berchet by stating: ‘I am not here to make you adopt the ideas I will give you as your own, but to teach you a true method for judging the things I will say’ (Giussani 2019, p. xxxi). The method was the test of experience and the human heart. He would repeatedly say to his students that faith in Christ is reasonable if it corresponds to the fundamental needs of the human heart. (Giussani 2019, p. xxxii).

In the preface to his extended essay, The Risk of Education (Giussani 2019), Giussani lays out three principles of such an education that respects the students’ freedom:

- ‘Education requires an adequate proposal of the past’, which he refers to as a ‘tradition’ and describes as ‘a hypothesis concerning meaning and an image of destiny’ (p. xxviii).

- ‘That proposal of the past must be presented within a present, lived experience that underscores its correspondence with the ultimate needs of the human heart’ (p. xxviii).

- ‘True education must be education to criticism.’ He notes that the root of the word criticism is krisis, which means to sift. In other words, students are gifted with the opportunity to reason and reflect on the proposal placed before them (p. xxix).

Giussani argued that if the student receives a tradition and holds it in crisis, this puts the dynamism of liberated reason to work and, as such, becomes an experience of freedom. In contrast, for a teacher to withhold elements of the tradition because they might prove offensive or too challenging for members of the classroom is an attack on the students’ freedom. It is to decide for them and refuse them an opportunity for verification, while also rendering the whole proposal incoherently fragmented and thereby obfuscating any possible verification.

So how did he communicate the proposal? Giussani would begin class with a provocation of some kind—forcing students to look closely at a concept by seeing it expressed in a myriad of different ways. The effect being that the commonalities across those different sources crystallised the theological concept under discussion whilst also revealing its relevance to reality.

He always began his lesson stating his thesis. Then he illustrated it by noting certain texts or other cultural references. He would quote Paul Claudel, Dante Alighieri, Giovanni Pascoli, Kierkegaard, Vladimir Solovyov, Alessandro Manzoni, Giacomo Leopardi, John Henry Newman, Charles Péguy, and Russian folk songs. The number of sources was amazing and overwhelming. He told us that he learned this approach from his teachers in the seminary: Fr. Carlo [Colombo] and Fr. Giovanni Colombo.(Savorana 2018, p. 179)

Sometimes Giussani would play classical music to illustrate a point. Then he would allow the students to respond with questions and comments. Given the anti-religious and, at times, anti-clerical attitudes in the room, this soon became ‘a very heated debate’ (Savorana 2018, p. 179). At the conclusion of the lesson, he would summarise the discussion by dictating notes from which students would reflect on the discussion and develop their own perspective before continuing the conversation in the next lesson.

One student summarised the goal of every lesson: ‘We had to face the exact, inescapable objectivity of Christianity.’ (Savorana 2018, p. 179). All the while students were provoked into responding. As Maddalena Kemeny recalled, the students ‘found themselves forced to take a stand regarding Christianity and the Church’ because of the way in which the ideas were presented. (Savorana 2018, p. 179). Another student who admitted to hating Giussani later wrote of their lessons together: “If you were honest, you couldn’t ignore the challenge of his position. At the same time, he was the head of the enemy party” (Savorana 2018, p. 185).

Many students were struck by the new dynamic in their class. Angelo Rizzoli17 argued that in provoking this experience of crisis, Giussani taught them the genuine meaning of freedom. ‘Before meeting him, in the classroom we were like prisoners who had to be quiet, good, and well behaved. Instead, with Giussani we could speak, ask things. He himself asked us questions and spoke to us about the world. We would ask him things that we believed (naively) would cause him trouble, but they never did’ (Savorana 2018, p. 188). Another student, Luigi Negri,18 recalled that Giussani was only ever angry for one reason. ‘He could not stand indifference and presumption… Ultimately those who would not put their freedom into play bothered him’ (Savorana 2018, p. 184).

6. Developing a Lesson Structure for the Contemporary Classroom

As a system of five secondary schools, our goal has been to develop a structure that will ensure the freedom of students is respected and they are given every opportunity to encounter the Christian proposal, undertake a process of verification and reflection, and respond in freedom. After some trial and error, we developed a structure featuring three movements: a provocation, building schema together, and a personal reflection.

It is important to clarify that a lesson is here being defined as the time it takes to teach a concept. It is not merely a single fifty-minute period of religious education. A familiar and simple concept might be taught in half a period. A completely novel concept might take two or three weeks. For the sake of clarity, I am going to use an example of teaching the event of Jesus’ birth to students in Year Seven. If my class has a high proportion of students who are unfamiliar with the biblical accounts—this lesson might run across several periods.

- 1.

- A Provocation

A provocation is some shared experience of reality that orients our focus towards reality and makes us look closely at the concept under discussion. It can be anything from a teacher sharing an anecdote, to a clip from a film, a piece of art, a scientific phenomenon, a short story, or even a class survey. The goal is to look at the same thing together and for that thing to provoke us into asking questions about reality.

For our class on the birth of Jesus, the provocation we might use is the story of the Chibok Girls who were kidnapped by Boko Haram on 14 April 2014. In 2022, Joe Parkinson and Drew Hinshaw published an account of the girls’ time in captivity. What amazed them was just how strong the girls were in the face of such brutal treatment. From the first day, the girls were told to abandon their belief in Jesus Christ, study the Quran, embrace Islam, and agree to become a wife to one of the terrorists. Stranded in the dense Sambisa Forest on the edge of the arid Sahel region, they had already witnessed their captors’ indiscriminate killing. They had also been told their village was captured and their families were dead. And yet, astoundingly they refused to comply with their captors’ demands. A crucial detail from Parkinson and Hinshaw’s book provokes important questions:

One schoolmate would ask for permission to go to the bathroom so she could find a bush to crouch behind and copy verses from a [smuggled] bible. She would return with a shorthand-replicated section. A popular choice was Luke chapter 2 verses 1 to 20, the story of Mary giving birth. Several of the girls memorised it.(Parkinson and Hinshaw 2021, p. 122)

This anecdote provokes certain questions:

- ○

- Why do you think the Chibok girls memorised the story of Jesus’ birth?

- ○

- Why would they repeatedly tell each other the story when the guards were out of earshot?

These are questions that foreground the enduring relevance of the birth of Jesus, and they challenge us to look closely at the event again. Regardless of a student’s religious affiliation or knowledge level, these are questions that inspire greater searching and allow for all our students to see the birth of Christ with fresh eyes. Crucially though, it would be possible to have an entirely different provocation to begin the lesson. A quick look at the fact that people all over the world build nativity scenes in their homes. How can this event featuring an extremely poor couple from 1st century Palestine have such universal relevance? A good provocation is simply a shared experience that lets students see the strangeness of the Christian fact, and the complementarity of that fact with the questions and desires of the human heart.

- 2.

- Building a Coherent, Christ-centred Schema Together

Here, we look more closely at the concept and build our knowledge as a classroom community. Contemporary students have access to huge amounts of information. They often complete tasks that have them gather information into worksheets. However, unless information is being formed as knowledge, this is often a training in cutting and pasting text from a web site to a document. Information only becomes knowledge when parts are meaningfully connected into a whole. Knowledge becomes wisdom when it speaks to what I am and compels an affirmation in my life. Students need to be given the space to stand back and see the pieces connected into a whole and then given time to reflect on the meaning of such a proposal in their lives.

For our lesson on the birth of Jesus Christ, we would read through Luke’s account, and there might be a handful of questions for students to answer, in order to draw their attention to the key points in the account. A shared reflection that cites the text, historical detail, and anything else that can clarify our vision of the event is then put before us. Who are Mary and Joseph? What is this moment reverenced all around the world? We might go deeper and look at the prophecies being fulfilled in this event or, if the class were quite familiar with the event, we might examine Luke’s strange foreshadowing of the cross and resurrection. But our goal is to examine the event and see it clearly. What is present here that might console young women living in captivity?

Building schemata together is very important in a subject like religious education in which so many of our students have such disparate levels of knowledge. This portion of the sequence often involves resources showcasing the conceptual pattern, shared reading, discussion, and summative note-taking. The goal is to hand over to the students a coherent overview of the concept to which they can return. Their role is to clarify understanding and begin to make connections between the content and the provocation.

- 3.

- A Personal Reflection

Finally, students are given the space to look closely at the schema we have developed and examine how it might speak to their lives. This is a space for verification, for testing, rather than simple recall. What does this mean? What is my response to this claim? What would it mean if it were true? What makes this beautiful? This portion of the sequence can involve written responses, conversations, prayer, and meditation. It can often involve silence and become a space for thought to grow.

The reflection might include stimulus material such as a painting or a piece of music. But the key is to give the students space to encounter a generative thought. Students might compose responses to the questions: How did Jesus give Mary and Joseph so much hope, even though they were effectively homeless? Now, thinking of the Chibok girls reciting the words of this Gospel event, how does this tiny baby still give people hope 2000 years later? The role of the teacher is to identify the pieces most suitable for their students and then lead them through the three movements of the proposal.

7. Accompanying Our Teachers—How We Work

The final two requests made by the teachers interviewed by Liz Dowling were the enhancement of their content knowledge and the enhancement of professional learning partnerships, both of which have taken on greater significance in the years since Dowling published her article.

The way we have sought to enhance teacher knowledge of the content has been to publish an online learning module to accompany each new Christ-centred unit of work that teachers are tasked with teaching; the assumption being that one can only meaningfully teach from the education one has received. Therefore, our teachers are right to demand such targeted educational opportunities.19

Each module is intentionally designed so that it would be impossible to simply share the link with students. All the material is structured according to the three movements of the lesson sequence; however, teachers then need to make a series of pedagogical decisions as to which pieces best suit and how they might communicate the information to their cohort. Can they replace the provocation with one of their own design? Which questions will they use? What depth of scriptural exegesis will suit the knowledge levels of their students? What is an effective classroom activity to help students engage with the ideas? They need to decide on the timing and the degree of releasing responsibility for students to work independently. In keeping with the Catholic principle of subsidiarity, teachers are always encouraged to use their own judgement and expertise in their classroom.

The modules have required a significant shift in thinking for many of our teachers. Previously, there was a self-reported tendency to view their roles in purely technological terms; they handed out resources and managed the learning environment. This was grounded in a loose confection of educational ideas that were often clumsily grouped under the heading of “student-centred learning”. This engendered, on the part of many teachers, an activity-first approach to planning. What am I going to be handing out? What will the students be doing in the lesson? What will hold their attention? The modules attempt to reorient the teachers’ work to a concept-first approach to planning. What are we examining? Which activities will ensure students examine the proposal more closely?

Giussani challenges us to develop a reality-centred classroom.20 It is a classroom in which the material and activities cohere to form a road of knowing in which the Christian proposal may be meaningfully encountered and explored step by step. For Giussani, this is the art of vision, and it is marked by an ever-deepening coherence. In that work, he affirms the particular (and therefore irreplaceable) role of the teacher as the source of coherence within the classroom community, continually and patiently [re]connecting the ‘shifting attitudes of the young person’ and ‘ultimate meaning’ (Giussani 2019, p. 43). This can be achieved by the teacher promoting and deepening the conceptual and structural coherence of religious education, moving between the parts and the whole, between the proposal and the lived questions of the human person. However, he argues that the teacher can only do that in a meaningful way—here, he uses the term authority—if they themselves have walked that road (Giussani 2006, p. 29). If they themselves have been provoked by the proposal they are tasked with sharing. Giussani argues that we do not follow a self-appointed authority—we “follow those who follow” (Fontolan 2006). The teachers who have allowed themselves to be formed by the educational proposition possess a credibility born of following something greater than themselves.21 It is this authority that allows for the teacher to communicate a generative thought to their students. He argues that it is the teacher’s role as witness—communicating the educative proposal at work in their own life—that is the most important element of this coherence.

To educate is to communicate one’s self, to communicate one’s way of approaching reality, for a person is a living mode of relating to reality. Our relationship with reality begins as a perception, a feeling, an attraction. It’s a project we are attracted to, a will to create bonds and to manipulate, a way of touching, using, and transforming reality. Therefore, to communicate one’s self means to communicate a living mode of relating to reality.(Giussani 1996, pp. 110–11)

However, where a teacher cannot give personal witness to the Christian claim in their own life, they can at least still improve their work by actively promoting the conceptual coherence of the proposition.

The final part of the puzzle is the way we have sought to enhance professional learning partnerships. This has seen us completely change the way we support RE teachers. Where before we would provide professional learning opportunities that were quite generalised, now we work alongside RE teachers in their classrooms. This involves modelling the new pedagogy, working with teachers to co-construct lesson sequences, and then delivering one period and observing the teacher deliver the next and sharing feedback, spending time unpacking particular concepts or resources. Teachers have certainly appreciated the more flexible and targeted modes of support, noting the obvious pragmatism of the approach.

8. Conclusions: Jesus Christ, Yes or No?

In his apostolic exhortation, Christus Vivit, Pope Francis reiterated the claim that ‘Catholic schools remain essential places for the evangelization of the young’ and, citing Veritatis Gaudium, he identified crucial features of the necessary methods for that work in a contemporary context. These included, ‘fresh experience[s] of the kerygma, wide-ranging dialogue, interdisciplinary and cross-disciplinary approaches, [and] the promotion of a culture of encounter…’ (Francis 2019, §222). It is tempting to allow the aspirational nature of Pope Francis’ writing to become the reason to ignore his call for a revitalised evangelisation within Australian Catholic education. However, in the work of Luigi Giussani, we find ourselves receiving fresh experiences of the kerygma, we find ourselves drawn into a wide-ranging dialogue and we find ourselves gifted with a method that has the capacity to reinvigorate our classrooms. Each of our students has the right to a religious education in which they contemplate the Christian proposal as a whole and are given the time and space to respond in freedom. This is our work—no more, no less.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For instance, the National Catholic Education Commission reports that 80% of primary school teachers and 61% of secondary school teachers identify as Catholic. Moreover, the NCEC advances that just 25% of the Catholic staff are engaged in regular worship and parish leadership activities. ‘For most staff, the Catholic school is their only regular experience of the mission and life of Catholicism. This includes the 29% nationally who are not Catholic or whose religious affiliation is not recorded’. Cited in (Hall and Sultmann 2019, p. 167). |

| 2 | As one teacher put it, ‘I believe that God is out there but apart from that it’s hard to know any more.’ Another participant put it in these terms, ‘My belief in God means there is something more out there...there is a force out there whether it’s one God or multiple Gods I’m not sure, but there is something out there.’ This conception of God lacked a personal referent and as such did not have a strong influence on conduct or how the world was understood. One teacher encapsulated this view well when she noted, ‘yeah I don’t think about God all that much...I know he is out there but apart from that I can’t say it’s a big part of how I think or see the world...just a bit too hard!’ An Empirical Investigation, (Rymarz 2017, p. 19). |

| 3 | The Evangelisation and Religious Education Team consists of a leader and three “education officers” and an admin support person, working with twenty-four primary schools and five high schools across a diocese twice the size of Belgium. Only one of those education officers works exclusively with the five secondary schools. |

| 4 | Thus, the National Catholic Education Commission argued: ‘[r]esponsive to the contexts in Australian Schools today, a Religious Education teacher requires deep knowledge and understanding, particularly of Scripture and Church teaching, gained through formal qualifications and accreditation according to the requirements of the local Bishop.’ (National Catholic Education Commission 2018). |

| 5 | ‘An event then can be defined as the emergence into experience of something that cannot be analysed in all of its factors, something that contains a vanishing point in the direction of mystery’ (Giussani et al. 2010, p. 15). |

| 6 | For more on the role of coherence in religious education, see Chigwidden (2022, pp. 20–35). But before moving on with the discussion, it is important to stress that Giussani was not promoting coherentism. As he makes plain in The Religious Sense, coherence is not an end in itself. ‘Logic, coherence, demonstration are no more than instruments of reasonableness at the service of a greater hand, the more ample “heart,” that puts them to use’ (Giussani 1997, p. 15). Coherence must always be in the service of freedom. And freedom says yes or no based on the criteria of the heart, which includes but is not limited to the criteria of reasonableness. So, coherence is best understood as the mark of meaningfulness which should pertain to any legitimate educative proposal. |

| 7 | Research emerging from the field of teacher education offers the useful distinction between conceptual, structural, and contextual coherence. Conceptual coherence being the order in which foundational ideas that comprise the vision are introduced to students, reflect classroom practice, and build upon one another. Program or structural coherence is the way in which all elements of the course (choice of pedagogy, order of the units, assessment choices, etc.) reflect the vision. Contextual coherence is the connection with lived experience and the extent to which alternate sources of knowledge either shape, accompany, or even displace foundational ideas. These concepts offer fruitful foci for any researcher concerned with perceptions of coherence in religious education because wherever contextual coherence is diminished, the need for conceptual and structural coherence increases. (Canrinus et al. 2019, pp. 192–205). |

| 8 | They were 47C2 (Sacred Time, Sacred Place) and 47C6, (Religion in the World) (Diocese of Wagga 2009, pp. 5, 11). |

| 9 | This term is crucial in any discussion of secularisation and religious education. The secular perspective—what Taylor terms the buffered-self, accepts only what the will has chosen as authentic and resists the idea of an objective and given world to which our mind desires to conform (Taylor 2007, pp. 37–38). However, this is not an original disposition. For this reason, Giussani talks about ‘elementary experience’ and ‘one’s own heart’ (Giussani 1997, p. 11). This elementary experience is revealed in the child who rushes to encounter reality with an attentive gaze, the baby trying to grab the water in the bath, the toddler lost in wonder examining the insect or reaching out to touch the lizard. This is the receptivity that Pieper (2009) famously described as leisure. It is what Heraclitus described as ‘listening to the essence of things’ (cited in Pieper 2009, p. 28). It is so fundamental to us that Aquinas ‘speaks of contemplation and play in the same breath’ (Pieper 2009, p. 41). To examine the religious sense is a return to that original orientation. It is to reassert the lived experience of metaphysics once more in a secular context. Giussani writes: ‘it is on myself that I must reflect; I must inquire into myself, engage in an existential inquiry’ (Giussani 1997, p. 5). Not only does such an inquiry create a shared grounding for religious education in a pluralistic setting, but it also re-establishes the very ground which makes meaningful religious education possible in the first place. |

| 10 | As John Paul II made plain, metaphysics is the doorway to a genuinely human religious education. ‘We face a great challenge at the end of this millennium to move from phenomenon to foundation, a step as necessary as it is urgent. We cannot stop short at experience alone; even if experience does reveal the human being’s interiority and spirituality, speculative thinking must penetrate to the spiritual core and the ground from which it rises. Therefore, a philosophy which shuns metaphysics would be radically unsuited to the task of mediation in the understanding of Revelation’ (John Paul II 1998, §83). |

| 11 | This should not be surprising. St Paul says to the Athenians ‘And [God] made every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth...that they should seek God, and perhaps feel their way toward him and find him. Yet he is actually not far from each one of us…’ Acts 17:26–27. Some two millennia later, the Church made effectively the same declaration in Gaudium et Spes: ‘For by his interior qualities he outstrips the whole sum of mere things. He plunges into the depths of reality whenever he enters into his own heart; God, Who probes the heart, (Jer. 17:10.) awaits him there; there he discerns his proper destiny beneath the eyes of God. Thus, when he recognizes in himself a spiritual and immortal soul, he is not being mocked by a fantasy born only of physical or social influences, but is rather laying hold of the proper truth of the matter.’ (Paul VI 1965, §14). |

| 12 | Giussani argues that what we describe as reasonable emerges from the correct method being applied to the correct object (Giussani 1997, p. 17). Since our object is the person of Jesus Christ, the method is imposed by the object (Giussani 1997, p. 21). By virtue of the incarnation, the object is a person; we are therefore tasked with encountering a real event, which becomes the question ‘who is Jesus?’ (Giussani 1998, p. 33). Giussani writes: ‘we have seen how the Gospel documents that belief, embraces the itinerary of conviction through a series of repeated recognitions which must be given space and time’ (Giussani 1998, p. 51). Thus, each event must be understood in relation to the person of Jesus Christ and in relation to the other events of his life and this is a matter of giving students the space and time to consider what they are being shown in the life of Jesus Christ. It also means that for a religious education, any socio-cultural detail is only reasonable by virtue of its ability to help us answer the question of who is Jesus Christ? To get a better sense of Giussani’s approach, it is worth contrasting his exegeses of Luke 19:1–10 and the story of Zacchaeus with what we might term a more ‘sociological approach’ given to us by the contemporary theologian and pedagogue Lievan Boeve. Let us begin with Giussani’s Christological exegesis. ‘This also happened to Zacchaeus, the senior tax collector, the most hated man in all of Jericho (Luke 19: 1–10). Surrounded by a great crowd, Jesus was passing by on the road, and Zacchaeus, a small man, was curious and climbed a tree for a better look. On reaching that tree, Jesus stopped, fixed his gaze upon him and cried: “Zacchaeus!” Then he said: “Come down quickly, because I must stay at your house today.” What suddenly struck Zacchaeus? What made him run joyfully home? Was he making plans for his vast wealth? Did he want to generously return his ill-gotten gains, to give half of his goods to the poor? What shook him and changed him? Quite simply, he had been penetrated and captured by a gaze that recognized and loved him for what he was. The ability to take hold of the heart of a man is the greatest, most persuasive miracle of all.’ Giussani then cites Rousselot whom he found quoted by de Lubac: ‘”Jesus imposes himself upon the conscience. He is at home in the innermost self of others… He does not limit himself to declaring a doctrine that is his through knowledge, that he has learned through Revelation: his concern, it might be said, is a personal affair”’ (Giussani 1998, pp. 53–54). The connection between the person of Jesus and the privacy of the human person’s conscience opens up the entire event by emphasising a universal significance. Moreover, we can discern a coherent pattern by observing the same thing in his conversations with the Samaritan woman, with Nicodemus, and with the figure of Pontius Pilate. In contrast, the sociologically informed exegesis provided by Lieven Boeve has a way of fragmenting the event by stressing contextual details that were unique to the time and place. Boeve writes: ‘Zacchaeus bears witness to the liberating event of Jesus’ word for a social outcast by acting in a liberating way himself. Jesus’ closing words have a bearing on the “event” that overcame Zacchaeus: “today salvation has come to this house because he too is a son of Abraham”. At the same time, they serve to typify the task Jesus had taken upon himself: “the Son of Man came to seek and save the lost”. According to Fitzmyer, these words are meant for the bystanders who had prematurely rejected Zacchaeus from their community’ (Boeve 2003, p. 126). The most obvious difference between the two exegeses is significant. Giussani begins with a focus on Christ, Boeve, with a focus on Zacchaeus. What is the effect? Giussani develops a harmonious vision that makes the testimony of the witnesses understandable in relation to the whole of Christ’s life. Boeve’s account seems to fragment the life of Christ and makes the testimony of the witnesses incoherent. Jesus being able to move hearts and minds with his gaze is in keeping with the Jesus whose voice stills the storm and who utters the seven-fold condemnation of the Pharisees (Matt 23:13–39) as he tries one more time to reach their consciences. In contrast, the Jesus who restores a tree-bound outsider to the community by virtue of an appeal to the Abrahamic patrimony is a man who solves a very specific situation with an appeal to a specific reality. It merely reveals ‘Jesus [as] someone who speaks and acts according to the praxis of the open narrative and is ultimately “pushed aside by the religious and political authorities”’ (Boeve 2003, p. 126). This is a fragment of the Gospels and we are left wondering, what are we to make of that peculiarly hegemonic Jesus intent on silencing the narratives of the Pharisees? Should we not mourn the lost schools of Hillel and Shammai, the teachers of the law ‘no longer able to have their say’? Should we, like the Pharisees, be angry when we hear that Jesus had silenced the Sadducees? (See: Matthew 22:29–33). Prioritising the sociological over the Christological has the effect of fragmenting the Gospel accounts and precludes an understanding of the whole. It is, in Giussani’s terms, incoherent by virtue of an unreasonable methodology, and therefore fails to honour the freedom of the students by making it more difficult to accompany the person of Jesus through all of the dimensions of his self-revelation, as the first disciples did. |

| 13 | Along with the word unity, the word miracle occurs throughout his ecclesiological work. (See: Giussani 2001, pp. 21, 73, 93–95, 127, 140, 146, 160, 171, 185, 221–23). |

| 14 | This view is perhaps best expressed in the writings of Lieven Boeve, ‘the catholic dialogue school intends to be a training ground for living (together) in a world that is characterised by diversity and difference. Critically-creatively learning to get along with what is familiar and what is different, with what unites and what distinguishes, enables people to contribute to an open, meaningful, tolerant and enduring society, where everyone has a place—a world of which God dreams too’ (Boeve 2019, p. 39). |

| 15 | An Italian philosopher and historian, Calogero published two books on education La scuola dell’ uomo (The School of Man), 1938, revised and reissued in 1956, and La scuola sot to Inchiesta (The School Under Scrutiny), 1957. Calogero’s metaphysics were often accused of promoting a solipsistic egoism in which the “I” is unable to find any form of genuine communion. Rather, each subject may expand their world by allowing for the reality of other persons. This making space becomes, for Calogero, the key ethic of altruism. Thus, in education, he argues that ‘the individual ego, that erstwhile solipsistic creature, emerges from its prison by recognizing other beings and entering into dialogue with them. Its respect for their existence demands an altruistic attitude, one of attempting to assist others in their own interests, and of helping them to expand their own worlds (Wolf 1984). In other words, there is no meaningful communion between persons but rather one becomes more and more like Caden Cotard’s warehouse in the 2008 Charlie Kaufman film Synecdoche New York. It is not hard to see why, for Giussani, such dialogue was simply not radical enough. |

| 16 | ‘Often the leaders of peoples, those with various claims to responsibility, if they are filled with common sense, favour a certain “ecumenism,” because they are terrified of war and violence, which are inevitable consequences when someone asserts only himself. So it seems that joining together, trying to respect each other’s identity might represent the realisation of eirene. But this is not peace, it is ambiguity. For at best this ends up as tolerance, in other words radical indifference’ (Giussani et al. 2010, p. 118). |

| 17 | Born into a powerful Italian business family, at the age of thirty-two he owned the popular newspaper Corriere della Sera. He would also become a significant film and television producer. |

| 18 | Later Archbishop of Ferrara-Comacchio (1 December 2012–15 February 2017). |

| 19 | Early in 2024, Wagga Diocese partnered with the University of Notre Dame, Australia to furnish a website called REShare with thirteen exemplar lesson sequences covering the life of Christ. See: https://www.notredame.edu.au/about-us/faculties-and-schools/school-of-philosophy-and-theology/sydney/reshare (accessed on 1 January 2024). |

| 20 | I developed this term before discovering that Gert Biesta has advocated a shift towards a ‘world centred’ education in opposition to the traditional dichotomy between student-centred or teacher/curriculum-centred education. It is interesting to note the post-metaphysical nuances of his language, reflecting his post-modern conception of reality, even as he remains unconsciously sympathetic to much of Giussani’s writing. ‘The idea of world-centred education is first of all meant to highlight that educational questions are fundamentally existential questions, that is, questions about our existence “in” and “with” the world, natural and social, and not just our existence with ourselves. The world, in other words, is the one and only place where our existence takes place. It is to highlight that the educational work in relation to this is about (re)directing the attention of the ones being educated to the world, which is why I agree with Prange’s suggestion that pointing is the fundamental operation of education’ (Biesta 2022, pp. 90–91). |

| 21 | ‘The experience of authority begins within us as the encounter with a person rich in knowledge of reality. This person strikes us as enlightening, and generates in us a sense of novelty, wonder, and respect. In this person is an unavoidable attractiveness, and in us an inevitable subjugation. Indeed, the experience of authority reminds us, more or less clearly, of our poverty and limitation. This leads us to follow and to make ourselves “disciples” of that person’ (Giussani 2019, p. 42). |

References

- Beria di Argentine, Chiara. 2021. The Faith of Fr. Luigi Giussani. Interview. New York Encounter. February 13. Available online: https://youtu.be/omDdDNtqlpY?si=qmwI_Laq8EJYb5it (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Biesta, Gert. 2022. World-Centred Education: A View for the Present. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boeve, Lieven. 2003. Interrupting Tradition: An Essay on Christian Faith in a Postmodern Context. Louvain: Peeters Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boeve, Lieven. 2019. Faith in dialogue: The Christian voice in the catholic dialogue school. International Studies in Catholic Education 11: 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canrinus, Esther T., Kirsti Klette, and Karen Hammerness. 2019. Diversity in Coherence: Strengths and Opportunities of Three Programs. Journal of Teacher Education 70: 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigwidden, Paul G. 2022. Catholic Education, The Art of Total Vision: Exploring the Role of Coherence in Religious Education. Review of Religious Education and Theology 2: 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Congregation for Catholic Education. 1982. Lay Catholics in Schools: Witnesses to Faith. Vatican Website. October 15. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/ccatheduc/documents/rc_con_ccatheduc_doc_19821015_lay-catholics_en.html (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Congregation for Catholic Education. 1988. The Religious Dimension of Education in a Catholic School: Guidelines for Reflection and Renewal. Vatican Website. April 7. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/ccatheduc/documents/rc_con_ccatheduc_doc_19880407_catholic-school_en.html (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Congregation for Catholic Education. 1998. The Catholic School on the Threshold of the Third Millennium. Vatican Website. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/ccatheduc/documents/rc_con_ccatheduc_doc_27041998_school2000_en.html (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Congregation for Catholic Education. 2014. Educating Today and Tomorrow: A Renewing Passion. Instrumentum Laboris. Vatican Website. April 7. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/ccatheduc/documents/rc_con_ccatheduc_doc_20140407_educare-oggi-e-domani_en.html (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- de Volder, Jan. 2010. The Spirit of Father Damien. Translated by John Steffan. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. [Google Scholar]

- Diocese of Wagga. 2009. Sharing Our Story: K-12 Religious Education Syllabus. Wagga Wagga: Catholic Schools Office. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, Elizabeth. 2012. Effective professional learning for religious educators: Some preliminary findings. Journal of Religious Education 60: 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Anthony. 2021. The Proliferation of Secularism and the Corrosion of Education. In The Inaugural Kathleen Burrow Research Institute Annual Lecture. Sydney: Catholic Schools New South Wales, May 26, Available online: https://www.csnsw.catholic.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/The-Proliferation-of-Secularism-and-the-Corrosion-of-Education.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Fontolan, Roberto. 2006. From Utopia to Presence: Presence, Judgment, and Authority. Traces. no. 8. September 1. Available online: http://archivio.traces-cl.com/2006E/09/presencejud.html (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Francis. 2013. Evangelii Gaudium. Apostolic Exhortation. Vatican Website. November 24. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_exhortations/documents/papa-francesco_esortazione-ap_20131124_evangelii-gaudium.html (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Francis. 2019. Christus Vivit. Apostolic Exhortation. Vatican Website. March 25. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_exhortations/documents/papa-francesco_esortazione-ap_20190325_christus-vivit.html (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Giussani, Luigi. 1996. The Risk of Education: Discovering our Ultimate Destiny. Translated by Rosanna M. Giammanco Frongia. New York: Crossroads. [Google Scholar]

- Giussani, Luigi. 1997. The Religious Sense. Translated by John Zucchi. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giussani, Luigi. 1998. At the Origin of the Christian Claim. Translated by Viviane Hewitt. Montreal: McGill Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giussani, Luigi. 2001. Why the Church? Translated by Viviane Hewitt. Montreal: McGill Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giussani, Luigi. 2005. Faith Is Given Us so that We Communicate It. Litterae Communionis-Traces. no. 1. Available online: https://repositoryscritti.luigigiussani.org/Sfogliatore/003294/index.html (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Giussani, Luigi. 2006. The Journey to Truth Is an Experience. Translated by John Zucchi. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giussani, Luigi. 2019. The Risk of Education: Discovering our Ultimate Destiny. Translated by Mariangela Sullivan. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giussani, Luigi, Stefano Alberto, and Javier Prades. 2010. Generating Traces in the History of the World: New Traces of the Christian Experience. Translated by Patrick Stevenson. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory of Nazienzen. 1953. Funeral Orations by Saint Gregory of Nazienzen and Saint Ambrose. Translated by Leo P. McCauley, John J. Sullivan, Martin R. P. McGuire, and Roy J. Deferrari. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, David, and William Sultmann. 2019. Formation for Mission: A Systems Model Within the Australian Context. In Global Perspectives on Catholic Religious Education in Schools. Edited by Michael T. Buchanan and Adrian-Mario Gellel. Singapore: Springer, pp. 165–77. [Google Scholar]

- John Paul II. 1998. Fides et Ratio. Encyclical Letter. Vatican Website. September 14. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_14091998_fides-et-ratio.html (accessed on 18 November 2024).